Introduction

Scholars of international relations have highlighted the growing politicization of international politics (Zürn, Reference Zürn2014). Proponents of the politicization thesis have argued that, with furthering globalization, international institutions’ policies and procedures have ‘become salient and controversial on the level of mass politics’ (Ecker-Ehrhardt, Reference Ecker-Ehrhardt2014: 1275). Beyond assessing the extent of the domestic and transnational politicization of international norms and institutions, research has concentrated on identifying the drivers behind this contestation, in particular, the relevance of classical ideological cleavages related to economic redistribution compared to new cleavages emerging as a consequence of globalization. These cleavages have been variously characterized as integration vs. demarcation (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Grande and Kriesi, Reference Grande and Kriesi2015), communitarian vs. cosmopolitan (Zürn, Reference Zürn2014; Zürn and de Wilde, Reference Zürn and Ecker-Ehrhardt2016), libertarian vs. traditionalist (Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010), or green/alternative/libertarian vs. traditional/authoritarian/nationalist (gal/tan) (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). This has been best documented in relation to European integration (de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) and areas of global governance such as trade, development, environment and public health (cf. Zürn and Ecker-Ehrhardt, Reference Zürn and de Wilde2013), but less so in the area of international security, in particular the use of armed forces in the context of international security operations.

However, as critically shown by episodes such as the Iraq war in 2003, decisions on military deployments can also become salient issues in domestic elections, polarize political elites and trigger both domestic and transnational social mobilization (cf. Danchev and Macmillan, Reference Danchev and Macmillan2005; Chan and Safran, Reference Chan and Safran2006; Schuster and Maier, Reference Schuster and Maier2006; Miyagi, Reference Miyagi2009; Kaarbo and Cantir, Reference Kaarbo and Cantir2013). Since the Iraq war, parliamentary votes on troop deployments in Europe have also become more common, with a growing number of countries having strengthened the rights of parliaments in the authorization of military operations (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017). The questioning of existing international military engagements has also figured prominently in the electoral programmes of some ascendant populist parties in Europe (Balfour et al., Reference Balfour, Emmanouilidis, Fieschi, Grabbe, Hill, Lochocki, Mendras, Mudde, Niemi, Schmidt and Stratulat2016). These examples suggest that a neglect of party politics in matters of the use of force is unjustified.

Although research on international security has long challenged the perspective that ‘politics stops at the water’s edge’ and has recognized the significance of domestic politics to security policy (cf. Rosenau, Reference Rosenau1966; Levy, Reference Levy1986; Hermann and Peacock, Reference Hermann and Peacock1987; Auerswald, Reference Auerswald1999; Gourevitch, Reference Gourevitch2002), little attention has been paid to ideological dimensions and to political parties specifically.Footnote 1 Likewise, comparative politics’ work on political parties rarely includes foreign and security policy as a relevant dimension of party politics (cf. Verbeek and Zaslove, Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2015: 525–526). In this paper though, we bring together insights from research on politicization, foreign policy analysis, and comparative politics to examine the party-political contestation of peace and security missions at the core of international security politics. We challenge the conventional wisdom, still extant in both international relations and comparative politics disciplines, that security issues generate cross-party consensus and we directly examine the role of party ideologies and party politics.

Going beyond single case studies, this paper addresses two inter-related questions: (a) to what extent deployment decisions are systematically contested amongst political parties, that is whether supporters and opponents cluster predictably in the political space and (b) what motivates and drives such contestation. We explore two types of data on party positioning on military missions by European democracies. First, we utilize experts’ estimates of political parties’ positions on peace and security missions in 31 European countries from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) to map parties and party families on both a standard left vs. right spectrum and the ‘new politics’ gal vs. tan dimension. Second, presenting the new Parliamentary Deployment Votes Database, we examine parliamentary votes on deployment decisions in France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Whereas the CHES data come with the advantage of covering a large number of countries, the voting data provide us with further insights into the degree and nature of contestation between and within political parties.

The paper proceeds in five steps. The second section sets the theoretical parameters of the analysis by elaborating on why we might expect party-political differences over the use of military force – a question often overlooked by mainstream theories in international relations, comparative politics, and by research on the domestic politics of security policy. Third section presents the data and methods in more detail. Special attention is given to the introduction of our new data set on parliamentary deployment votes in France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Fourth section shows the results of our empirical analyses. We first report to what extent deployment decisions are contested amongst political parties using both CHES data and an Agreement Index (AI), adapted from studies of the European Parliament, to compare the degree of contestation of military deployments with other policy areas. We then investigate the drivers of party contestation over security missions, looking both at the effect of ideological cleavages and of parties’ position in government and opposition. Last section concludes by summarizing the findings and discussing the implications for current debates on the politicization of international politics.

Party-political contestation of military missions

Traditionally, neither students of international relations nor their colleagues in comparative politics expect a great deal of party-political contestation over foreign policy, particularly security policy. International Relations scholars historically treated states as unitary actors and tended to examine national interests and national identity rather than competing party-political visions over foreign policy. Neorealists, for example, expect states to rationally unify in response to the imperatives of anarchy. Constructivists, in turn, tend to focus on international norms and logics of appropriateness, operating at the systemic level, with norms internalized by the state as a whole. Even constructivists who look inside the state at identities, roles, and ontological security also tend to assume a unified state as the key actor (cf. Cantir and Kaarbo, Reference Cantir and Kaarbo2016: 3–9). Liberalism either remains at the system level (neoliberalism) or places the focus on public opinion and democratic institutions (democratic peace). Even if parties do have underlying differences on matters of security, scholarship on international conflict has often assumed that these differences might be suppressed in the face of external threats (Simmel, Reference Simmel1955; Levine and Campbell, Reference Levine and Campbell1972; Huddy, Reference Huddy2013). International crises bring about, at least temporarily, a rally around the flag-effect (Waltz, Reference Waltz1967: 273; Oneal et al., Reference Oneal, Lian and Joyner1996) that unites domestic political actors and makes criticism of the government look inappropriate. According to the Copenhagen School, when elites securitize issues – that is, framing them as a matter of security, they take them beyond normal politics and out of bounds for party contestation (Buzan et al., Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998: 29). Taken together, the idea that politics stops at the water’s edge suggests that dissent on deployment decisions is rather unlikely as such votes may transcend party politics and demonstrate national unity instead.

Although theories of international relations are increasingly incorporating domestic political factors (Kaarbo, Reference Kaarbo2015), and Foreign Policy Analysis has, for decades, focused on the domestic politics of international relations, there has been very little attention to parties as ideational and political agents in security policy. Within the study of comparative politics, in turn, scholars emphasize that the emergence of political parties is best understood as a response to domestic conflict (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Conflicts over foreign and security politics do not figure prominently in explanations of party systems, which have emphasized economic, cultural and religious cleavages (Boix, Reference Boix2007: 513). The few studies that focus on the role of political parties in politicizing international governance have also concentrated on economic and cultural issues, most notably trade and migration (Ecker-Ehrhardt, Reference Ecker-Ehrhardt2014). When addressed, contestation on security issues is more often related to the phenomenon of transnational politicization, for example the emergence of anti-war (global) protest movements, rather than its role in the domestic political and electoral spheres (cf. Lichbach and de Vries, Reference Lichbach and de Vries2007). Overall, therefore, it is generally assumed that voters care more about party positions on other issues, particularly domestic policy and economic pocket-book issues, and thus have little motivation to distinguish themselves in security policy.

More recently, however, research on foreign policy has suggested that foreign and security policy is indeed an important area of disagreement among political parties (see, e.g., Bjereld and Demker, Reference Bjereld and Demker2000; Özkeçeci-Taner, Reference Özkeçeci-Taner2005; Schuster and Maier, Reference Schuster and Maier2006; Devine, Reference Devine2009; Kaarbo, Reference Kaarbo2012; Calossi et al., Reference Calossi, Calugi and Coticchia2013; Clare, Reference Clare2014; Verbeek and Zaslove, Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2015; Pijovic, Reference Pijovic2016; Chryssogelos, Reference Chryssogelos2018; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2017). Because foreign policy, including military missions, can be salient to voters and influence voting behaviour (cf. Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Gelpi, Feaver, Reifler and Thompson Sharp2006; Gartner and Segura, Reference Gartner and Segura2008; Clements, Reference Clements2013), political parties have incentives to court public opinion and distinguish themselves from one another on security issues (cf. Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004; Bow and Black, Reference Bow and Black2008; Clare, Reference Clare2010; Mello, Reference Mello2012; Hildebrandt et al., Reference Hildebrandt, Hillebrecht, Holm and Pevehouse2013; Joly and Dandoy, Reference Joly and Dandoy2016). Much of the previous research, however, has focused on single countries or episodes, or on the relationship between ideological factionalism and international conflict. There is yet no comparative analysis of the extent to which parties systematically differ on military operations across countries. This paper addresses this gap by examining the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Decisions on the deployment of armed forces are systematically contested amongst the political parties in a country.

A full exploration of the topic, however, requires going beyond the parties matter-argument to examine motivations behind parties’ orientations towards military deployments. We are particularly interested in the extent contestation of military missions corresponds to general cleavages that have been identified by scholars of party politics and recent studies on the politicization of international affairs (see below). The most prominent of such cleavages is, of course, the left/right one that emerged during the industrial revolution and remains highly influential to the present day (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Koch and Sullivan (Reference Koch and Sullivan2010) argue, for example, that positions on the use of armed force abroad result from positions on social policy because the armed forces and the welfare state compete for the same resources. Therefore, political parties that promote the welfare state tend to oppose large armies, expensive military procurement as well as the actual use of armed force abroad. Studies on the actual use of force find support for a left/right cleavage as ‘right governments are more likely to be involved in militarized disputes than are left governments’ (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, London and Regan2004: 13; see also Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004; Arena and Palmer, Reference Arena and Palmer2009; Clare, Reference Clare2010, Reference Clare2014; Oktay, Reference Oktay2014; Williams, Reference Williams2014).

Changing values in society, globalization, migration and the emergence of supranational authority have led students of party politics to consider additional cleavages that pit winners of globalization against losers (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) and/or proponents of post-materialist and cosmopolitan values against traditionalists and communitarians (Zürn and de Wilde, Reference Zürn and Ecker-Ehrhardt2016; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). The relevance of this cleavage has been established more broadly for parties’ positions on European integration and globalization but has not been examined for military missions. Because military missions of the post-Cold War period are no longer about territorial defence and are more often justified as ‘saving strangers’ (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2000) from state-sponsored violence and repression, the use of armed force may resonate with cosmopolitan values of human security and equality (Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004).

Taken together, we derive two propositions from the literature on party-political cleavages:

Proposition 2: Party-political contestation of military missions is structured by a left/right cleavage with right parties more supportive of such missions than left parties.

Proposition 3: Party-political contestation of military missions is structured by a post-materialist/cosmopolitan vs. traditionalist/nationalist cleavage with parties scoring high on post-materialism/cosmopolitanism being more supportive of such missions than parties scoring high on traditionalism/nationalism.

Although the left/right as well as the post-materialism/traditionalism cleavage can easily be applied to military missions, students of the partisan theory of public policy (as well as structural theories of international relations) have argued that for security and defence policy, the ideological disposition of governments may be superseded by pressures emanating from the international system. Hans Keman, for example, argued that geopolitical factors are particularly important for defence spending and render domestic politics by and large irrelevant (Keman, Reference Keman1982: 192). Even though the end of the Cold War might have created more room for political manoeuvre when it comes to wars of choice, ‘systemic pressures to cooperate’ (Kreps, Reference Kreps2010: 192) remain high. Sarah Kreps argues that in NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, political parties chose to forgo electoral gains because they were sensitive to the high reputational costs of defection from a joint intervention (see also Schultz, Reference Schultz2001). In addition, high levels of path dependency and bureaucratic routines make any substantial policy changes to on-going and inherited force commitments very difficult (Goldmann, Reference Goldmann1982; Hermann, Reference Hermann1990). However, in contrast to Kreps, who sees not only governing parties but elites in general under pressure to contribute to joint interventions, we argue that such pressures are primarily felt in government and thus expect political parties in government to factor them into the positions they take, whereas parties in opposition remain less constrained from such considerations. This logic is consistent with Lewis’ (Reference Lewis2017) claim that when in power, political parties tend to become more internationalist and interventionist. Moreover, parties in opposition have a general incentive to present themselves as an alternative to the ones in government and thus to oppose government policies, even on deployment decisions. According to Williams (Reference Williams2014: 112–113), if opposition parties perceive a military mission ‘as being unpopular or potentially disastrous, then they will publicly oppose using force’ (see also Schultz, Reference Schultz2001). This leads us to our fourth proposition:

Proposition 4: In government, political parties are, ceteris paribus, more supportive of military missions than in opposition.

It should be noted, however, that any test of this proposition may be subject to a selection effect, as the agenda-control is by and large in the hands of the government.Footnote 2 In other words, although governments frequently ‘inherit’ troop deployments from their predecessors, they still have some room of manoeuver to adjust troop size, mandate, rules of engagement and caveats to the prevailing mood in parliament. Therefore, while our data show that backbench opposition is not uncommon, especially in the United Kingdom, we do not expect this proposition to be falsified. Nevertheless, taking parties’ position in government or opposition into account will act as an important control for testing our other propositions in the multivariate regression below.

Methodology

To examine the party-political contestation of military missions, we use expert survey data on political parties’ positions as well as data from a new data set on parliamentary votes on deployment decisions. The expert survey data come from the two latest rounds of the CHES in 2010 and 2014, which included a question on peace and security missions (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk J, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015b; Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017). Under the heading ‘position towards international security and peacekeeping missions’, experts are asked to determine a political party’s position on a scale from 0 (‘strongly favours COUNTRY troop deployment’) to 10 (‘strongly opposes COUNTRY troop deployment’).Footnote 3 More than 300 experts mapped the positions of political parties.Footnote 4

As in the previous survey, experts were also asked to map political party positions on a left/right and a gal/tan axis: Experts are asked ‘Please tick the box that best describes each party’s overall ideology on a scale ranging from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right)’. On gal/tan, experts are asked: ‘Parties can be classified in terms of their views on democratic freedoms and rights. Libertarian or post-materialist parties favour expanded personal freedoms, for example, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation. Traditional or authoritarian parties often reject these ideas; they value order, tradition, and stability, and believe that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues’ (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk J, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015b: 144). 0 indicates extreme gal and 10 extreme tan.Footnote 5

Finally, we make use of the notion of party families to cluster parties into groups with shared core values and interests and to examine whether there are significant differences across the main party families. Data on family membership come from CHES. We exclude the Confessional/Protestant, Agrarian and Regionalist/Ethnic party families as well as all parties that are coded as not belonging to any family. Furthermore, we merged the party families Conservatives and Christian Democrats into one category because they occupy comparable positions in the countries we studied in depth. We thus explore differences between the main party families, namely Conservatives/Christian Democrats (criscon), Socialists, Liberals, Greens, Radical Left, and Radical Right.

The merits and shortcomings of expert survey data in comparison to the data of the manifesto research group (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel, Werner, Lacewell and Schultze2013) have been extensively discussed.Footnote 6 Our decision to use the CHES expert survey data does not result from taking sides in this dispute but is motivated by the data’s validity for the purpose of this paper: whereas the CHES data specifically include a question about ‘peace and security missions’, the manifesto data handle the rather broad categories ‘military: positive’, ‘military: negative’, and ‘peace: positive’; additionally, manifesto coders are instructed to interpret ‘military’ to include defence spending, force levels, rearmament, and treaty obligation. Thus, for our purposes, we consider the CHES question to capture this study’s attempt at measuring party-political contestation over military missions more precisely.

For the deployment votes, we compiled a new database, Parliamentary Deployment Votes, in which we collected data on a total of 183 roll-call votesFootnote 7 in plenaries for the period between 1991 and August 2016 in France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 8 These four countries have played important roles in military missions but represent different constitutional traditions and political-strategic cultures. Together, these four countries account for approximately two-thirds of defence spending in the EU. Across the four countries under study, the practice of voting on military missions differs enormously (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017). The German Bundestag has ex ante approval rights for military missions due to a Federal Constitutional Court ruling in 1994 and has voted more than 140 times since, partly because extensions, changes in mandate or troop levels require parliamentary approval. The French parliament was only endowed with ex post voting rights on military operations through the constitutional reform of 2008 (Ostermann, Reference Ostermann2017). In Spain, parliamentary control of military missions had become an issue in the wake of the 1999 Kosovo intervention, but it was only after the highly contested involvement of Spain in the 2003 Iraq war that an ex ante veto power was introduced, by means of an Organic Law, in 2005. In the United Kingdom, deployment votes are rare because of former royal prerogatives but have become more common in the wake of the 2003 Iraq War and have even led some to see this as a new convention (Strong, Reference Strong2014; Mello, Reference Mello2017).Footnote 9 To make deployment vote data comparable across parties and reflect the interest in government-opposition dynamics, we calculate averages of no-votes per party during a given legislative term (the full data set contains disaggregated and aggregated data on every single vote).Footnote 10 Our coding of party families is based on the CHES coding.

The data on deployment votes also allows us to investigate the extent of party-political contestation of deployment decisions as compared to other matters. To capture the degree of dissent within parliament as a whole, we calculate an AI that Hix et al. (Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2005) originally developed to measure party cohesion in the European Parliament.Footnote 11 The AI equals 1 when all MPs vote together and it equals 0 when they are equally divided between the voting options. This index has become an established measure to assess the unity of groups within legislatures – mostly political parties, but in studies of the European Parliament also members of the same country. To our knowledge, the AI has not been used to measure degrees of consensus within a parliament as a whole,Footnote 12 most likely because the recording of individual votes already is a sign of contestation; uncontroversial parliamentary decisions are often adopted without the time-consuming recording of individual votes. Moreover, parliaments differ enormously in the ways they vote, with some often recording votes and others doing so only rarely (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld1995). Hence, recorded votes may be a very unrepresentative sample of all votes in a parliament (Carruba et al., Reference Carruba, Gabel and Hug2008). Yet for the purposes of this study, the AI allows an assessment of the degree of dissent on military mission votes and on any other matters in our four countries. This allows us to examine to what extent party politics indeed stops at the water’s edge.Footnote 13

A final note of caution applies to both data sources: neither the CHES nor the deployment vote data distinguish between different types of missions. Such differentiation would be particularly welcome for testing our third proposition on the impact of a party’s gal/tan position because we can safely assume that humanitarian missions are more appealing to parties at the gal-end of the spectrum than counter-terrorism missions, whereas the opposite applies to parties at the tan-end of the spectrum. Except for a few ideal-typical cases, however, military interventions are notoriously difficult to categorize. Governments typically evoke a combination of justifications for a military intervention, often blending humanitarian motivations with self-defence (as was the case in the 2003 Iraq war and the 2014 strikes against Daesh) to appeal to various segments of society. The relative weight of these justifications is often at the center of the party-political debates that we study in this paper. Any classification of military interventions would therefore also be in tension with our point of departure that foreign and security policy is politically contested. For the purpose of this paper then, we explore party positions on military missions in general.

Findings

Degree of contestation: does politics stop at the water’s edge?

Table 1 contains our calculation of the AI. It shows the average degree of contestation of military missions compared to other business for every legislative term under study. Two findings are worth highlighting: first, degrees of contestation vary significantly across countries and legislative terms. They range, for instance, from high contestation on military missions with an AI equalling 0.46 for the Cameron II government in the United Kingdom to low contestation with an AI equalling 0.98 for the Zapatero II government in Spain. This means that military missions are neither uncontroversial nor highly contested as such. For France, contestation moves between AIs of 0.66 (Sarkozy presidency) and 0.94 during François Hollande’s term. Germany gives testament to a similar spread with AIs ranging from 0.62 (highest contestation) to 0.95 (lowest). Whereas in Spain, decisions are highly consensual and the number of no-votes of the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) and the left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) are negligible, in the United Kingdom, deployment votes have been much more controversial. The second finding is that levels of contestation of military missions in all four countries are clearly lower than those for other legislative business. In the Zapatero II government in Spain cited above, the AI for other business equals 0.68, a considerable difference of 0.3 with the military mission AI. In France during Hollande’s term (2012–2017), the difference between mission AI (0.94) and other business-AI (0.54) is even larger, reflecting the majority’s split on many policy issues with its own president, compared to high multi-partisan support for military missions.Footnote 14 The only exception to this finding is the Cameron II cabinet. The average AI in this case, however, is based on a single vote (on using force against Daesh). In general, though, the AI shows that politics may not stop at the water’s edge but it tends to become less contested.

Table 1 Agreement Indexes

While the AI demonstrates that deployment decisions are indeed contested, it does not provide any additional information of where dissent originates. For a better understanding of the pattern of contestation of military missions, we thus examine whether political parties systematically disagree about deployments. We first use the CHES data on parties’ support for military missions.Footnote 15

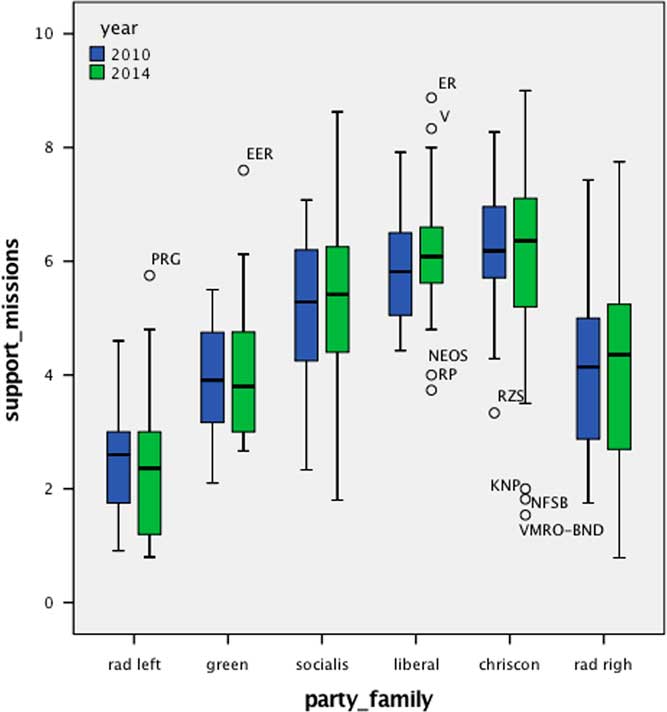

As Figure 1 visualizes, and as the ANOVA analysis in Table 2 demonstrates, party families systematically differ in the degree to which they favour their country’s participation in peace and security missions, as stated in Proposition 1. As a comparison of the standard deviations shows, differences within most party families increased, thus pointing to higher levels of contestation. Green parties are more supportive than radical-left parties, and socialist parties are more supportive than green and radical-left ones. A notable exception is the French Parti radical de gauche (PRG), which CHES experts gauged as more supportive than the Greens. Support is highest amongst Liberals and Christian Democrats/Conservatives, with some outliers in Central and Eastern European countries. The Radical Right is about as supportive as the Greens. Although the boxplot shows considerable variation within party families, the ANOVA analysis reported in Table 2 demonstrates that differences between party families are statistically highly significant. The data also suggests that the gap between the Radical Left as the main party family most consistently opposing peace and security missions and the parties of the centre is widening, rather than narrowing.

Figure 1 Boxplot of party families’ support for peace and security missions. PRG=Parti radical de gauche (France); EER=Erakond Eestimaa ohelised (Estonia); ER=Eesti Reformierakond (Estonia); V=Venstre (Denmark); NEOS=Das neue Österreich (Austria); RP=Twój Ruch (Poland); RZS=Red, zakonnost i spravedlivost (Bulgaria); KNP=Kongres Nowej Prawicy (Poland); NFSB=Natsionalen Front za Spasenie na Bulgaria (Bulgaria); VMRO-BND=VMRO–Bulgarsko Natsionalno Dvizhenie (Bulgaria).

Table 2 ANOVA analysis of support for peace and security missions across party families

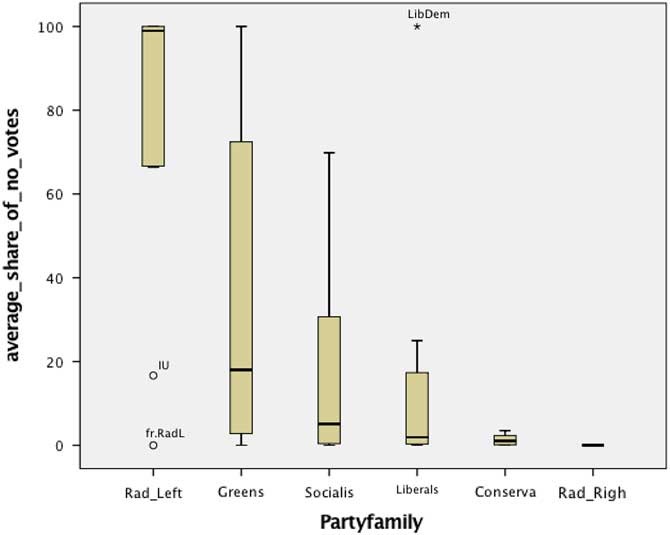

P<0.001 between-group comparison for both 2010 and 2014

Our collection of deployment votes allows us to further examine whether a similar pattern of contestation can be observed in actual votes on military missions. Figure 2 visualizes the average share of no-votes during a legislative term across party families. Figure 2 supports our first proposition that the deployment of armed forces is systematically contested amongst political parties. The figure shows that differences across party families are even more pronounced in actual votes. The boxes and whiskers also indicate, however, that there is a considerable spread: radical-left, green, and liberal parties have all voted both unanimously for and against military deployments throughout a particular legislature. Of course, whether a party is in government or in opposition impacts on its voting behaviour. In France, for example, radical-left PRG lawmakers are often part of left-wing majorities or part of the government and therefore vote in line, contrary to the other parties in their family. In the United Kingdom, all Liberal MPs voted against the Iraq war in 2003 but most of them voted for interventions in Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, and Daesh in Iraq when in government.Footnote 16 In Spain, the radical-left Izquierda Unida (IU) has never given its approval to any mission but has abstained on several occasions – mainly EU maritime surveillance and training operations and UN-led missions. IU’s choice for abstention (instead of voting directly against) was most frequent during the Zapatero II term, when Socialists held a minority government, thus often dependent on the votes of IU and other regional parties.Footnote 17 In Germany, Social Democrats and Greens voted in favour of military missions when in government but were less supportive when in opposition. We will come back to the impact of being in government or opposition when running a multivariate regression analysis below.

Figure 2 Average share of no-votes across party families in the four countries under study. IU=Izquierda Unida (Spain); fr. RadL=Parti communiste français (PCF) and Parti radical de gauche (PRG) combined; LibDem=Liberal Democrats (United Kingdom).

Differences in support across party families are, however, by and large akin to those in Figure 1: support is lowest among parties of the Radical Left, followed by Greens and Socialists. Christian Democrats and Conservatives, as well as Liberals, are generally supportive of military deployments with considerably decreasing shares of no-votes. Voting data differ from CHES data as regards the Radical Right: whereas the experts have gauged them to be unsupportive of peace and security missions, our voting data reveal that they never voted against any deployment decision. However, the empirical basis for this finding is very small: in the four countries under study, only two MPs of the Front national in the 2012–2017 legislature of the Assemblée nationale and a single MP of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) in the 2015–2017 House of Commons represent radical-right parties; additionally, these MPs took only part in a small number of votes.

Taken together, expert survey and voting data demonstrate that military missions are contested among political parties. To be sure, the degree of dissent tends to be lower than for other, mostly domestic, issues, which suggests that the politics stops at the water’s edge idiom impacts on the politics of military deployments. By clustering political parties into families, we demonstrate, however, that political parties differ systematically on the use of force abroad: expert survey and voting data concur that Christian Democrats/Conservatives are more supportive than Socialists, who are in turn more supportive than the Greens and the Radical Left. The two data sources only differ as regards the Radical Right: whereas experts find it almost as opposed to military missions as the Greens, voting data suggest they are the most supportive of all parties. Because of their limited representation in parliament, however, the finding on the Radical Right is far from robust and will require further research in the future.

Drivers of contestation: old or new politics?

Having demonstrated that military missions are politically contested, we now turn to the question of what motivates contestation. Specifically, we examine the three possible drivers discussed above, namely a party being either in government or opposition (Proposition 4), its position on the left/right axis (Proposition 2) and on the gal/tan axis (Proposition 3).

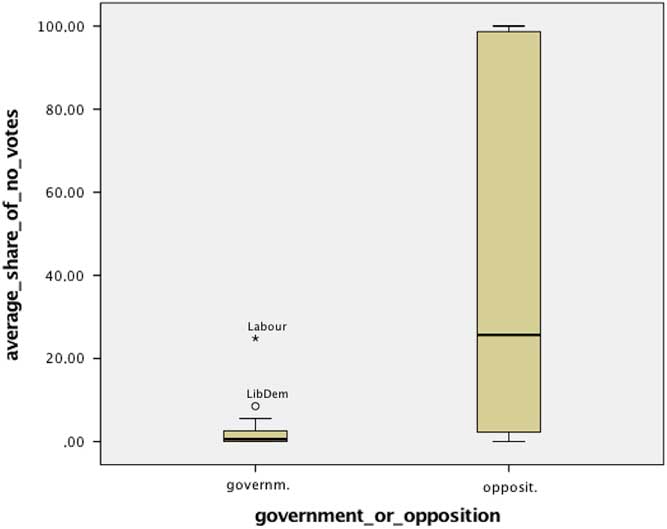

We begin by examining the impact of being in government or in opposition. Figure 3 demonstrates that there is indeed strong evidence for our fourth proposition: membership in government has a statistically significant (P<0.001) impact on the number of no-votes when parliament decides on military deployments: the average number of no-votes per party per legislature differs between 42.8% (in opposition) and 2.4% (in government).Footnote 18 Outliers all come from the United Kingdom: In 2003, 84 out of 338 Labour MPs voted against their own government on the Iraq war. Whilst part of the Cameron/Clegg government, Liberal Democrats mostly voted with the government but the average number of no-votes increased: 10 out of 42 Liberal Democrats voting against their own government on a possible Syrian intervention in 2013.

Figure 3 Comparison of average share of no-votes between parties in government and parties in opposition in the four countries under study.

To be sure, the enormous differences in voting against military missions might also result from a selection effect: Die Linke, for example, may vote against deployments because it is free to do so in opposition, but one can also argue that it is in opposition because it fundamentally opposes a key element of German security policy. Looking at political parties that move in and out government, however, suggests that voting behaviour is indeed partly driven by the constraints of being in office: the average share of no-votes amongst German Social Democrats and Greens dropped dramatically when in government (1998–2005) and rose again once back in opposition. In France, whereas 175 Socialists in the Assemblée nationale and 87 socialist senators voted against the Afghanistan mission extension in 2008 whilst in opposition, only one Socialist in the Assemblée nationale voted against Libya in 2011, and no socialist senator at all when the Parti Socialiste (PS) was in government.

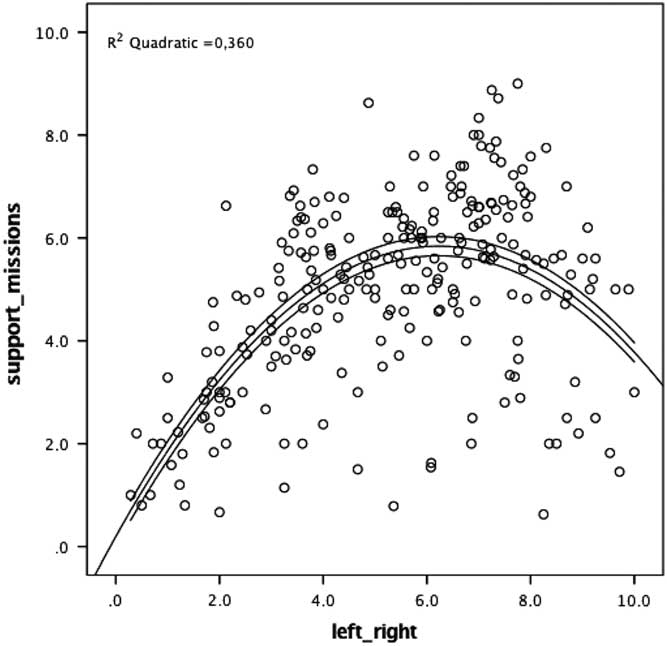

The CHES data on political parties’ left/right and gal/tan positions are particularly useful to examine whether contestation of military missions is driven by an overarching ideological cleavage, that is whether contestation reflects different fundamental values across the political spectrum. A previous study used data from the 2010 CHES to demonstrate that party-political contestation over military missions follows a curvilinear left/right pattern (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017). The 2014 CHES data allow us to examine whether this finding holds for 2014 as well. Figure 4 demonstrates that it does, in line with our second proposition. In terms of the left/right cleavage, the correlation is indeed curvilinear: using a quadratic model, the correlation is statistically significant at the 0.001 level with a r 2 of 0.36 (2014).Footnote 19 Support for peace and security missions increases as one moves from the left to the centre right and declines again towards the radical right.

Figure 4 Mapping of political parties’ positions on military missions and on a left/right scale, 2014.

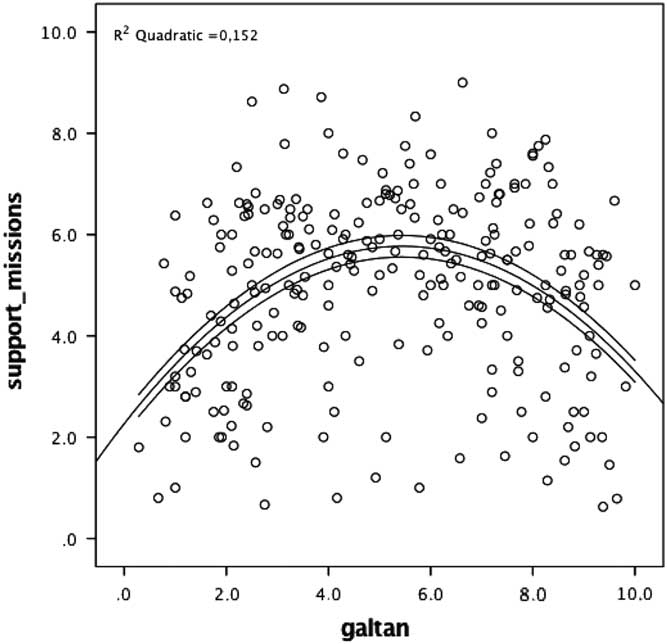

Figure 5 shows that support for military missions also differs along the gal/tan scale, as stated in our third proposition: Political parties that score high on being either green/alternative/libertarian or traditional/authoritarian/nationalist are both less supportive of deploying armed forces than those in the middle of this scale. The 2014 data in Figure 5 demonstrate that the gal/tan scale is a highly significant predictor but explains less variation than the left/right scale (for 2014, r 2 equals 0.15). Compared to 2010, the differences in variation explained have declined (0.36/0.15 for 2014 vs. 0.35/0.11 for 2010). Additional data from future surveys are needed to judge whether this is a significant trend.

Figure 5 Mapping of political parties’ positions on military missions and on a GAL/TAN scale, 2014.

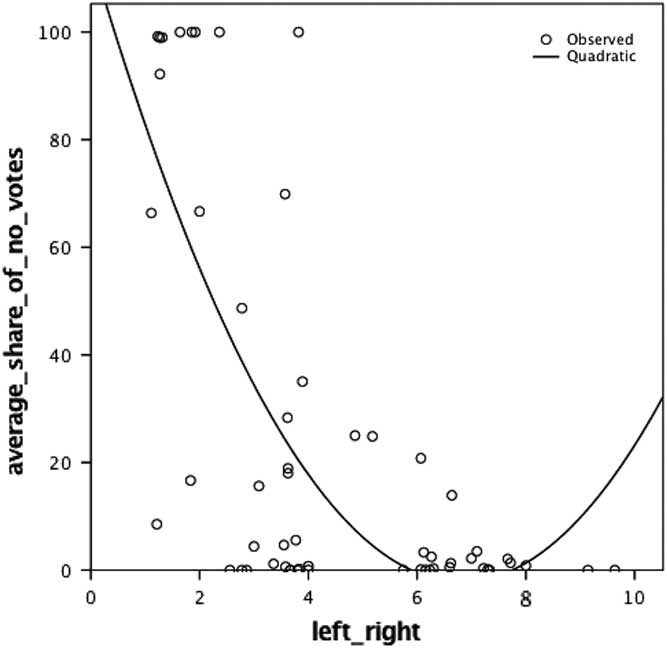

Again, our voting data allow us to triangulate the drivers of political contestation. The actual deployment votes in our four countries confirm the importance of the left/right cleavage. However, in contrast to the CHES data, the actual votes suggest a linear relationship, with the Radical Right in France and with the UK supportive of military deployments. Figure 6 visualizes political parties’ positions on the left/right scale and their average share of no-votes in parliamentary deployment decisions. The scatterplot shows that the share of no-votes within a political party decreases as one moves from the (far) left to the (far) right of the political spectrum, again in line with our second proposition. Parties of the Radical Left, such as Die Linke in Germany and IU in Spain, sometimes voted unanimously against military deployments. The only time some MPs of Die Linke ever voted in favour of a military mission in Germany was when the Bundeswehr was called in to support the destruction of chemical weapons in Syria in 2014. The Greens were the traditional home of the German peace movement and initially shared the Radical Left’s principled opposition to military missions. Even though the Bundeswehr’s early deployments were non-combat missions, the Greens consistently voted against them during Helmut Kohl’s fourth government between 1990 and 1994. Starting after the 1994 elections, however, the Greens embarked on a painful process of recalibrating their position on the use of force (Vollmer, Reference Vollmer1998). Spurred on by the future Foreign Minister Fischer, this process was highly conflictual but also signalled to the Social Democrats that a possible coalition would be feasible. When in government between 1998 and 2005, the share of no-votes dropped indeed but remained consistently above the share amongst Social Democrats. Back in opposition (from 2005 on), the share of no-votes rose again but not to the level of the pre-government period. A closer look shows that the Greens are especially divided over the Afghanistan missions. At the same time, their opposition against the Bundeswehr’s contribution to the EU-led maritime operation against human trafficking and their support for the missions in Darfur, South Sudan, Bosnia, and Kosovo have been unanimous.

Figure 6 Mapping of political parties’ positions on a left/right scale and share of no-votes in parliamentary deployment votes [we attribute 2010 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) scores for left/right (Figure 6) and GAL/TAN (Figure 7) to the legislative terms of Merkel II (2009–2013), Zapatero II (2008–2011), Sarkozy (2007–2012), and the British House of Commons votes in the period 2010–2013. 2014 CHES scores are attributed to Merkel III (2013–2017), Rajoy I (2011–2015), Holland (2012–2017), and the House of Commons votes in 2014 and 2015. Christian Democrats in Germany, Liberals and Radical Left in France consisted of two or more political parties whose CHES scores were then weighted according to their share of seats in parliament].

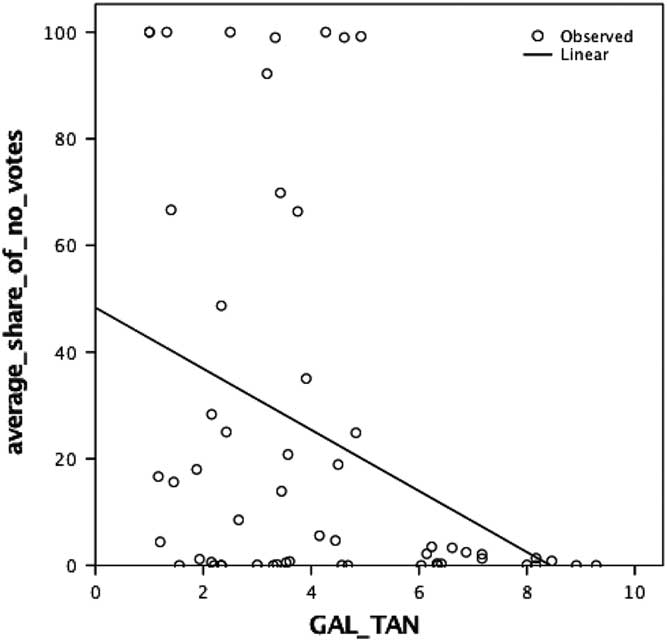

Figure 7 visualizes political parties’ positions on the gal/tan scale and their average share of no-votes in parliamentary deployment decisions. The scatterplot demonstrates that the average share of no-votes decreases as one moves from the green/alternative/libertarian end of the spectrum to the traditional/authoritarian/nationalist end, as stated in our third proposition. A closer look shows that political parties’ positions on the gal/tan dimension often resemble those on the left/right axis: UKIP and the Front national mark the far end on both scales; on the other end of the spectrum, radical-left and green parties switch positions but both remain in the left half of the spectrum. Yet, a curve estimation of the left–right and gal/tan models demonstrates that the correlation of the left–right model with support for deployments is far stronger than for the gal/tan model. In the linear model, 38% of the variation in voting is explained by the left–right scale; in the cubic model, more than 50% of variation is explained. For gal/tan, only around 13% of the variance in support for missions is explained by the gal/tan scale (for gal/tan, linear and cubic models hardly differ).

Figure 7 Mapping of political parties’ positions on a GAL/TAN scale and share of no-votes in parliamentary deployment votes.

The figures thus far provide evidence for both governmental constraints and ideological contestation. In order to gauge the relative predictive power of government/opposition, left/right and gal/tan, we run a multivariate regression analysis with the average share of no-votes as dependent variable. We test several models to assess the impact of these variables on their own and in combination with each other. Table 3 shows that a party’s left/right score has a strong and highly significant effect on a party’s average share of no-votes in a legislative term. The effect is strongest when controlling for both gov/opp and gal/tan but the effect is strong and statistically significant across different models. The predictive power of a party’s position on the gal/tan is smaller and melts away if left/right is controlled for. The effect of gov/opp is also strong but remains weaker than left/right. It is statistically highly significant in any combination with other predictors. Taken together, therefore, we can conclude that actual party behaviour in parliament is driven by both governmental constraints and ideological contestation, especially as connected to parties’ positions on the left/right scale.

Table 3 Multivariate regression analysis

N=56; coefficients are standardized

***P<0.01.

Conclusion

Decisions on the use of armed force are at the heart of security and defence policy, an issue area that has remained underexplored by students of party politics. Although deployment decisions have often been framed in terms of a national interest that transcends particular interests, our analysis shows that they are not exempted from party-political contestation: political parties in Europe systematically disagree on whether their country should participate in peace and security missions. Moreover, in line with recent studies on politicization of European integration and international affairs, our analysis of the CHES data indicates that differences in support for military operations across parties are growing over time rather than narrowing.

Whereas the CHES data provide us with expert judgments on parties’ general positions on military missions, our new Parliamentary Deployment Votes Database allows us to gain additional insights into how political parties act when asked to support an actual mission in parliament. Our analysis shows that being part of the governmental majority or of the opposition has a big impact on a party’s actual voting. However, the government/opposition logic is not the most important factor in explaining differences in voting behaviour. Instead, the strongest predictor of how supportive a political party is of actual military deployments is its position on the left/right axis: support is lowest amongst parties of the Radical Left and increases as one moves along the left/right axis to the Greens, the Social Democrats, the Liberals, and the Christian Democrats and Conservatives.

The findings thus indicate that debates on the use of armed forces in Europe are still structured around the ‘old’ welfare-oriented cleavage, rather than a ‘new’ culturalist cleavage emerging in response to the twin dynamics of globalization and Europeanization. However, evidence for the positioning of parties on the Radical Right is still inconclusive. The CHES data suggest that they are less supportive of military missions than the parties of the centre and the moderate right. In contrast, deployment vote data suggest high levels of support but should be treated with great caution as they are derived from very few MPs and votes in just two countries. Whether support for peace and security missions relates to the left/right axis in a linear or curvilinear way, therefore, remains an item for further research.

Another item for future research is the disaggregation of military missions. The CHES data inquire about peace and security missions in general and the deployment vote data report averages per legislative term, thus lumping together peacekeeping, peacemaking, humanitarian intervention, and self-defence. Our analysis demonstrates that this is not necessarily a problem because systematic party-political differences on peace and security missions in general clearly exist and are just as meaningful as differences over, for example, European integration in general. Nevertheless, disaggregating deployments in terms of purpose, justification under international law, risks for troops, international organization in charge, etc. is a promising way to gain additional insights into patterns and drivers of contestation of military missions.

Overall, this study contributes to the long-standing tradition of research on the domestic politics of international conflict but follows new ways. We demonstrate that the party system is an important site of contestation as regards military missions, thus redressing the relative lack of research on parties as important actors in security policy. Going beyond the parties matter-claim, this study advances research on political parties and foreign policy by unpacking the different ideological dimensions as well as political incentives and logics driving parties’ positions and voting on military missions. This analysis not only bridges previous research from international relations on politicization, from comparative politics on political parties, and from foreign policy analysis on domestic politics processes, but our findings also connect perspectives on ideologies and ideas with more institutional approaches. Political parties, as carriers of ideologies housed in institutional–political contexts, are an ideal subject to examine these connections.

Acknowledgments

The authors received valuable comments and suggestions from Sebastian Bödeker, Brian Burgoon, Aron Buzogany, Pieter de Wilde, Benjamin Faude, Piet Hays Gries, Jonas Hagmann, Dieuwertje Kuijpers, Matthias Kranke, Onawa Lacewell, Thomas Malang, Ignacio Molina, Andrew Neal, Kai Oppermann, Trineke Palm, Brian Rathbun, Christian Rauh, Tapio Raunio, Mathew Stephen, Alexandros Tokhi, Paul van Hooft, Gijsbert van Iterson Scholten, Mariken van der Velden, Michael Zürn, members of the University of Edinburgh IR Research Group, and the anonymous reviewers.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000097

Appendix

Table A1 Appendix. Roll-Call Votes in France, Germany, Spain and the United KingdomFootnote a