Decisional capacity is a term that has its origins in legislation, but has considerable implications for clinical practice. Definitions vary but research in this area has centred on a model published by Paul Appelbaum and Thomas Grisso in 1995, who conceptualised capacity in terms of four abilities: ability to communicate a choice, ability to understand relevant information, ability to appreciate relevant information and ability to manipulate information rationally. Reference Appelbaum and Grisso1 In healthcare, treatment decision-making capacity – hereinafter referred to as ‘capacity’ – is closely related to agency (the capacity of a person, or ‘agent’, to take intentional action), autonomy and the exercise of self-governance, concepts that are fundamental to human dignity and rights. Reference Owen, Freyenhagen, Richardson and Hotopf2 For example, Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recognises the right to be recognised as a person before the law, and the subsequent right to have one's decisions legally recognised. Autonomy and empowerment are thought to be essential components of patient-defined recovery from psychosis, Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison3,Reference Law and Morrison4 and mental health legislation frequently requires clinicians to empower patients to make decisions and to make an assumption of capacity until proved otherwise, e.g. the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act (2000) and the Mental Capacity Act 2005. However, there is also a concern that if patients who lack capacity to make specific decisions are allowed to make these decisions, then these may not reflect their true wishes, with the consequence being a poor outcome and inadequate protection of the patient. Reference Lepping and Raveesh5 Capacity has understandably been called the ‘gatekeeper for autonomy’. Reference Donnelly6 Lepping et al found that the average percentage of patients with impaired capacity on psychiatric wards is 45%. Reference Lepping, Stanly and Turner7 Despite the frequency with which psychiatrists are asked to make such judgements, almost half of them view the evidence base in this area as weak. Reference Hamann, Cohen, Leucht, Busch and Kissling9 Nonetheless, the field of decision-making capacity research has grown in recent years. This has been spurred on by changes in legislation, but also by a change in the culture in which healthcare decisions are made. People using mental health services are showing a greater desire to be included in decisions about their treatment, Reference Hamann, Cohen, Leucht, Busch and Kissling9 and there has been an increasing emphasis on ensuring not only that patients give informed consent to treatment, but also that they are actively involved in the decision-making process. 10 The most common model for such involvement is called ‘shared decision-making’, but there is evidence that people with psychosis do not typically experience this. 11 Since impaired capacity is a major barrier to psychiatrists implementing shared decision-making with people with psychosis, Reference Hamann, Mendel, Cohen, Heres, Ziegler and Buhner12 improving our understanding of factors that cause or maintain this impairment may help to change this. Moreover, British Medical Association guidance on assessing and managing capacity advises that it is the duty of the assessing clinician to enhance capacity where it is possible to do so. 13 In the context of psychiatric and mental health conditions, this is often achieved through treatment of the condition itself; however, there has been little research on the effectiveness of current treatments for enhancing decision-making capacity. Although some studies have examined whether specific psychological and educational interventions can enhance capacity, Reference Carpenter, Gold, Lahti, Queern, Conley and Bartko14,Reference Naughton, Nulty, Abidin, Davoren, O'Dwyer and Kennedy15 the overall evidence is surprisingly limited.

Previous reviews have examined the prevalence of incapacity in psychiatric patients, Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf16 the reliability and validity of measurement tools, Reference Dunn17,Reference Sturman18 the degree of impairment in decisional capacity in schizophrenia, Reference Jeste, Depp and Palmer19 the role of poor insight, Reference Ruissen, Widdershoven, Meynen, Abma and van Balkom20 and the role of specific neuropsychological deficits. Reference Palmer and Savla21 Although one older review examined the correlates of capacity in psychiatric populations generally, Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf16 no review has yet looked at the factors associated with capacity in psychosis specifically. Identifying these factors might help us develop a clinically useful theoretical model, which in turn would aid the development of effective interventions to support capacity. Thus, the primary objectives of this systematic review were to identify which clinical, demographic and treatment-related variables are associated with treatment decision-making capacity in psychosis and, where a sufficient number of comparable studies exist, to use meta-analysis to produce pooled estimates of the magnitude and reliability of any relationship.

Method

To minimise the risk of selective reporting bias and maximise transparency, a protocol for the systematic review was registered in advance with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42015025568). The protocol was updated to include a quantitative synthesis of effect sizes using meta-analytic procedures where three or more studies provided usable data, and incorporation of the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess outcome quality (online supplement DS1). Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello22

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were published in English before October 2015, included a reliable and valid assessment of capacity in adults diagnosed with a non-affective psychotic disorder and provided data on the association between capacity and at least one other clinical or demographic variable (online supplement DS2). Assessment of capacity was accepted as valid if participants had been asked to make a real or hypothetical decision about a healthcare or treatment decision, and if a valid and reliable tool was used to measure at least one of the four accepted domains of decisional capacity described above. Reference Appelbaum and Grisso1 Studies reporting usable cross-sectional or longitudinal data were eligible for inclusion regardless of overall study design or purpose. Studies were excluded where the proportion of participants with non-affective psychosis was less than 50%. Since we were specifically investigating correlates of treatment decision-making capacity, and because capacity is a decision-specific concept, we excluded studies where only capacity to consent to participate in research or legal proceedings was examined.

Search strategy

A search using the terms (Schizo* OR Psychosis) AND (Capacity OR Decision making OR Consent) AND (Treatment OR Health care) was conducted in the databases EMBASE, EMBASE Classic, Medline and PsycINFO from 1947 to October 2015. One researcher (A.L.) conducted the search (with support and training from a qualified librarian), and another (P.H.) provided supervision and consultation. Previous reviews and included studies were hand-searched for additional studies, and authors were contacted for any further unpublished studies.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search were screened to eliminate obviously ineligible studies such as studies of unrelated conditions, or other reviews. The full-text reports for any remaining studies were then examined to determine eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (online supplement DS3).

Quality assessment

In line with previous systematic reviews, Reference Taylor, Hutton and Wood23,Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton24 the assessment of observational study quality was conducted using an adapted version of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) assessment tool. Reference Williams, Plassman, Burke, Holsinger and Benjamin25 The adequacy of the methods used to select the cohort, the sample size, the methods used to assess outcomes, the degree of missing data and the appropriateness of the analytic methods used were all assessed as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘partial’ or ‘can't tell’ (online supplement DS4). Randomised controlled trials were assessed using the well-established Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool, which assesses risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases. Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman26 An adapted version of GRADE was used to assess the quality of the effect size estimates, whether derived from single studies or groups of studies. Specific criteria for assessing outcome quality within the GRADE approach are outlined in online supplement DS5.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted when at least three studies reported usable data on the relationship between a particular variable and treatment decision-making capacity. These were conducted using MetaXL software. Correlations were transformed into Fisher's Z, and a random effects model using the DerSimonian & Laird method was used to compute an overall effect size, together with 95% confidence intervals. Reference DerSimonian and Laird27 This approach allows for true heterogeneity in effect size magnitude (due to differences in measurement, sample, etc.) to be distinguished from sampling error. Reference Borenstein28 Fisher's Z, estimates were then back-transformed to Pearson's r to allow interpretation according to Cohen's 1988 conventions (0.1 small, 0.3 moderate, 0.5 large). Reference Cohen29

Results

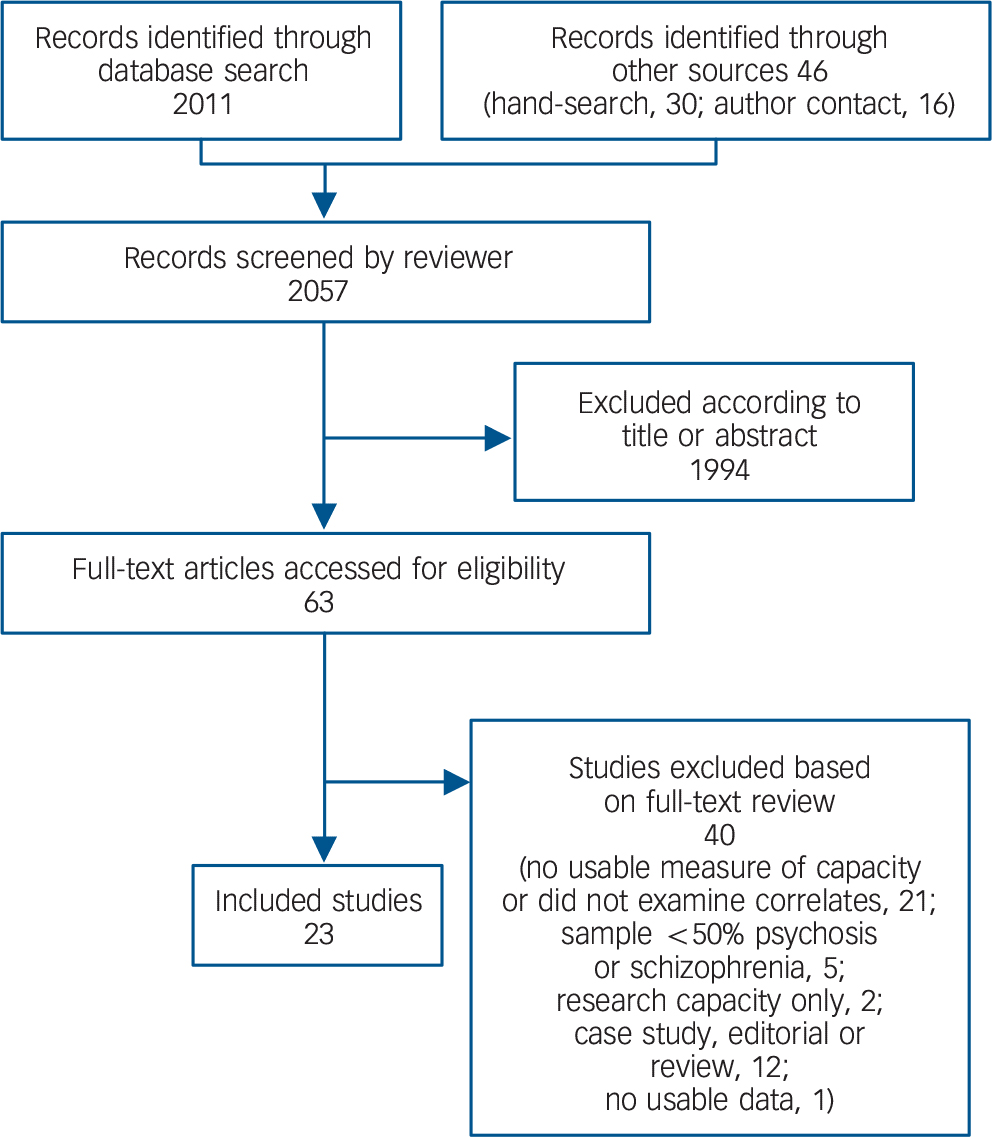

Of the 2057 papers initially identified, 1994 were excluded after inspection of title or abstract (Fig. 1). Full-text publications were sought for the remaining 63 papers. Of these, 40 were excluded: 21 did not include a measure of capacity or did not examine or report correlates, 12 were case descriptions, editorials or reviews, 4 examined a different population and 2 examined research decision-making capacity. A full list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion is provided in online supplement DS3. A total of 23 studies were included for review (Table 1). These provided data on the relationship between capacity and symptoms (fc = 12), insight (k = 4), affect (k = 3), cognitive performance (k = 6), executive functioning (k = 2), duration of illness (k = 2), education (k = 5), metacognition (k = 1) and various interventions (k = 10). ‘Metacognition’ refers to the implicit and explicit awareness, knowledge, beliefs and understanding we have about our cognitive systems and processes.

Fig. 1 Study selection.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

| Participants | Baseline demographics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Total n |

Proportion with psychosis, % |

Country | Measure of capacity |

Variables measured (name of measure) |

Age, years: mean (s.d. or range) |

Proportion female, % |

Treatment setting |

| Cairns et al (2005) Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson35 | 112 | 55 | England | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Insight (SAI-E) Cognition (MMSE) Coercion (BPCS) |

37.2 (11.8) | 37 | In-patient |

| Capdevielle et al (2009) Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36 | 60 | 100 | France | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) Insight (SUMD) Depression (BDI-2) Anxiety (STAI) |

36.3 (10.9) | 28 | Out-patient |

| Di & Chen (2013) Reference Di and Cheng70 | 192 | 100 | China | SSICA | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Years of education |

30.3 (15.2) | 19 | In-patient |

| Dornan et al (2015) Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy48 | 37 | 89 | Ireland | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) Functioning (GAF) |

32.3 (19.8–56.4) |

8 | In-patient (forensic) |

| Elbogen et al (2007) Reference Elbogen, Swanson, Appelbaum, Swartz, Ferron and Van Dorn38 | 469 | 59 | USA | DCAT-PAD | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Functioning (GAF) Insight (ITAQ) Cognition (AMNART; WAlS-III; COWAT; HVLT) |

42 (10.7) | 60 | Out-patient |

| Grisso & Applebaum (1991) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum71 |

26 | 100 | USA | MUD | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Depression (BDI) Cognition (WAIS-R) |

36.8 (NS) | 31 | In-patient |

| Grisso & Applebaum (1995) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum72 |

75 | 100 | USA | UTD, POD, TRAT |

Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Depression (BDI) Cognition (WAIS-R) |

35.4 (7.4) | 48 | In-patient |

| Grisso et al (1997) Reference Grisso, Appelbaum and Hill-Fotouhi31 | 40 | 100 | USA | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) | 39 (NS) | 20 | In-patient |

| Hamann et al (2011) Reference Hamann, Mendel, Meier, Asani, Pausch and Leucht49 | 61 | 100 | Germany | Clinical | Controlled trial; no correlationa data reported |

40.7 (11.7) | 62 | In-patient |

| Howe et al (2005) Reference Howe, Foister, Jenkins, Stene, Copolov and Neks73 | 110 | 81 | Australia | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) | 37.2 (12.3) | 51 | In-patient |

| Kennedy et al (2009) Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy45 | 88 | 74 | Ireland | MaCAT-T | Uncontrolled trial; no other correlational data reported |

NS | 9 | In-patient (forensic) |

| Koren et al (2005) Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33 | 21 | 100 | Israel | MacCAT-T | Metacognition (WCST) Cognition (WAIS-R) |

23.9 (4.5) | 38 | In-patient |

| Kleinman et al (1996) Reference Kleinman, Schachter, Jeffries and Goldhamer44 | 26 | 100 | Canada | Knowledge of medication |

Controlled trial; no correlationa data reported |

NS | NS | In-patient |

| Mandarelli et al (2012) Reference Mandarelli, Parmigiani, Tarsitani, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti34 | 45 | 56 | France | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Cognition (WCST) Cognition (MMSE) |

41 (13.1) | 55 | In-patient |

| Munetz & Roth (1985) Reference Munetz and Roth42 | 25 | 88 | USA | Questionnaire | Uncontrolled trial; no other correlational data reported |

48.6 (NS) | 66 | NS |

| Naughton et al (2012) Reference Naughton, Nulty, Abidin, Davoren, O'Dwyer and Kennedy15 | 19 | 95 | Ireland | MacCAT-T | Uncontrolled trial; no other correlational data reported |

36.7 (10.6) | 100 | In-patient (forensic) |

| Owen et al (2008) Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf74 | 40 | 100 | England | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) Cognition (WAIS-R) Insight (SAI-E) |

NS | NS | In-patient |

| Palmer et al (2002) Reference Palmer, Nayak, Dunn, Appelbaum and Jeste43 | 16 | 94 | USA | MacCAT-T; HCAT |

Psychotic symptoms (PANSS, BPRS) Cognition (DRS) |

54.6 (7.2) | 44 | Out-patient |

| Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 | 60 | 100 | France | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) Insight (BCIS) Depression (BDI-2) Anxiety (STAI) |

36.8 (11.1) | 32 | Out-patient |

| Rutledge et al (2008) Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy32 | 102 | 88 | Ireland | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) Functioning (GAF) |

38.1 (16.2) | 9 | In-patient (forensic) |

| Schacter et al (1994) Reference Schacter, Kleinman, Prendergast, Remington and Schertzer75 | 59 | 100 | Canada | Questionnaire | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) | 37 (NS) | 17 | Out-patient |

| Wong et al (2000) Reference Wong, Clare, Holland, Watson and Gunn46 | 19 | 100 | England | Interview | Psychotic symptoms (BPRS) | 40.1 (10.6) | 24 | Out-patient |

| Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 | 81 | 100 | Hong Kong | MacCAT-T | Psychotic symptoms (PANSS) Depression (MADRS) Insight (DAI) Cognition (WAIS-R-HK; WCST; WMS; MCT) |

36.9 (10.4) | 46 | In-patient |

AMNART, American National Reading Test; BCIS, Beck Cognitive Insight Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-2, Beck Depression Inventory – 2nd edn; BPCS, Brief Perceived Coercion Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; DAI, Drug Attitude Inventory; DCAT-PAD, Decisional Competence Assessment Tool for Psychiatric Advance Directives; DRS, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HCAT, Hopkins Competency Assessment Test; HVLT, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; ITAQ, Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire; MacCAT-T, MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool-Treatment; MADRS, Montgomery & Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MCT, Monotone Counting Test; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; MUD, Measuring Understanding of Disclosure; NS, not stated; PANSS, Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale; POD, perceptions of Disorder; SAI-E, Expanded Schedule for the Assessment of Insight; SSICA, Semi-structured Inventory for Competence Assessment; STAI, Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory; SUMD, Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder; TRAT, Thinking Rationally about Treatment; UTD, Understanding Treatment Disclosure; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – 3rd edn; WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WAIS-R-HK, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised – Hong Kong; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Task; WMS, Wechsler Memory Scale.

Quality assessment

Overall GRADE ratings for each outcome are presented in the right-hand columns of Tables 2, 3 and 4. Quality ratings using the AHRQ measure of observational and uncontrolled intervention studies are shown in online Tables DS1 and DS2, and online Table DS3 provides Cochrane risk of bias ratings for randomised controlled trials. The studies generally performed well on the AHRQ and Cochrane risk of bias assessments. Methods used to assess key outcomes were generally reliable and valid, cohorts were as a rule well described and characterised, and most of the studies selected their participants in a relatively unbiased way (although convenience samples were widely used). The evidence was weakened by a general failure to provide prespecified power calculations. Although only a minority of studies (k = 5) had masked rater assessment of the relevant outcomes, we made a post hoc decision to exclude this from the quality assessment. Intervention studies often did not include a follow-up assessment. Funnel plots did not detect evidence of publication bias for the majority of the outcomes, but there were generally too few studies to assess this properly. Reference Ioannidis and Trikalinos30

Table 2 Summary of meta-analytical estimates

| Outcome (number of studies) |

Included studies | n | Pooled Fisher's Z (95% CI) Pooled r (95% CI) |

Heterogeneity (I 2 for Z), % |

Quality (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship between total symptom severity and understanding (9 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Grisso & Applebaum (1991) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum71 Grisso & Applebaum (1995) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum72 Grisso et al (1997) Reference Grisso, Appelbaum and Hill-Fotouhi31 Howe et al (2005) Reference Howe, Foister, Jenkins, Stene, Copolov and Neks73 Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Rutledge et al (2008) Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy32 Schacter et al (1994) Reference Schacter, Kleinman, Prendergast, Remington and Schertzer75 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

610 |

Z = −0.49 (−0.62 to −0.35) r = −0.45 (−0.55 to −0.33) |

60 | Moderate (−1 risk of bias) |

| Relationship between total symptom severity and appreciation (6 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Grisso et al (1997) Reference Grisso, Appelbaum and Hill-Fotouhi31 Howe etal (2005) Reference Howe, Foister, Jenkins, Stene, Copolov and Neks73 Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Rutledge et al (2008) Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy32 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

453 |

Z = −0.24 (−0.33 to −0.14) r = −0.23 (−0.14 to −0.32) |

0 | Moderate (−1 risk of bias) |

| Relationship between total symptom severity and reasoning (7 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Grisso & Applebaum (1995) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum72 Grisso et al (1997) Reference Grisso, Appelbaum and Hill-Fotouhi31 Howe et al (2005) Reference Howe, Foister, Jenkins, Stene, Copolov and Neks73 Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Rutledge et al (2008) Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy32 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

528 |

Z = −0.32 (−0.52 to −0.12) r = −0.31 (−0.48 to −0.12) |

80 | LOW (−1 risk of bias, −1 inconsistency) |

| Relationship between depression and understanding (3 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Grisso & Applebaum (1991) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum71 Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 |

146 |

Z = −0.04 (−0.21 to 0.13) r = −0.04 (−0.20 to 0.13) |

0 | Moderate (−1 imprecision) |

| Relationship between verbal IQ and understanding (4 studies) |

Grisso & Applebaum (1991)

Reference Grisso and Appelbaum71

Grisso & Applebaum (1995) Reference Grisso and Appelbaum72 Koren et al (2005) Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

203 |

Z = 0.45 (0.20 to 0.69) r = 0.42 (0.20 to 0.60) |

60 | Low (−1 risk of bias, −1 imprecision) |

| Relationship between verbal IQ and reasoning (3 studies) |

Grisso & Applebaum (1995)

Reference Grisso and Appelbaum72

Koren et al (2005) Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

177 |

Z = 0.42 (0.27 to 0.57) r = 0.39 (0.26 to 0.51) |

0 | Low (−1 risk of bias, −1 imprecision) |

| Relationship between years of education and understanding (3 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

201 |

Z = 0.49 (0.35 to 0.63) r = 0.46 (0.34 to 0.56) |

0 | Moderate (−1 imprecision) |

| Relationship between years of education and reasoning (3 studies) |

Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

201 |

Z = 0.26 (0.12 to 0.40) r = 0.26 (0.12 to 0.38) |

0 | Moderate (−1 imprecision) |

Table 3 Summary of individual observational study findings

| Correlate (number of studies) |

Studies included | n | Outcome measures used |

Key findings | Quality (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive functioning (2 studies) |

Koren et al (2005)

Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33

Mandarelli et al (2012) Reference Mandarelli, Parmigiani, Tarsitani, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti34 |

66 | WCST | Some evidence of large correlations in one study, but no clear evidence in the other |

Very low (−1 risk of bias, −1 inconsistency, −1 imprecision) |

| Insight (5 studies) | Cairns et al (2005)

Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson35

Capdevielle et al (2009) Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36 Owen et al (2009) Reference Owen, David, Richardson, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf37 Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 Elbogen et al (2007) Reference Elbogen, Swanson, Appelbaum, Swartz, Ferron and Van Dorn38 |

813 | SUMD, SAI-E, BCIS, ITAQ | Insight strongly and significantly associated with capacity, and reasoning in particular |

Moderate (−1 risk of bias, −1 indirectness, +1 large effects) |

| Duration of illness (2 studies) |

Raffard et al (2013)

Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39

Wong et al (2005) Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 |

141 | Years since diagnosis | Some evidence of small correlation in one study, but no clear evidence in the other |

Low (−1 risk of bias, −1 imprecision) |

| Metacognitive ability (1 study) |

Koren et al (2005) Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33 | 21 | Participant ratings of confidence in the correctness of the sort (0–100) |

Metacognitive ability found to be associated with capacity |

Moderate (−2 imprecision, +1 large effect) |

| Perceived coercion (1 study) |

Cairns et al (2005) Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson35 | 112 | BPCS | Participants judged to have impaired capacity were more likely to report high perceived coercion |

Moderate (−1 imprecision) |

| Anxiety (2 studies) | Capdevielle et al (2009)

Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36

Raffard et al (2013) Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 |

120 | STAI | Both state and trait anxiety had small to medium positive correlations with appreciation and reasoning, but not with understanding or communicating |

Moderate (−1 imprecision) |

BCIS, Beck Cognitive Insight Scale; BPCS, Brief Perceived Coercion Scale; ITAQ, Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire; SAI-E, Expanded Schedule for the Assessment of Insight; STAI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SUMD, Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Table 4 Summary of individual interventional study findings (non-randomised controlled trials)

| Intervention | Studies included | n | Outcome measure | Key finding | Quality (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altering presentation of material (5 studies) |

Kennedy et al (2009)

Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy45

Kleinman et al (1996) Reference Kleinman, Schachter, Jeffries and Goldhamer44 Munetz & Roth (1985) Reference Munetz and Roth42 Palmer et al (2002) Reference Palmer, Nayak, Dunn, Appelbaum and Jeste43 Wong et al (2000) Reference Wong, Clare, Holland, Watson and Gunn46 |

176 | Change in capacity scores |

Altering presentation of material associated with improved capacity |

Low (−2 risk of bias) |

| Treatment as usual (antipsychotic medication) (2 studies) |

Dornan et al (2015)

Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy48

Owen et al (2011) Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Richardson47 |

237 | Change in capacity scores |

Treatment as usual (including antipsychotics) associated with improved capacity |

Moderate (−2 risk of bias, +1 large effect) |

| Shared decision-making (2 studies) |

Elbogen et al (2007)

Reference Elbogen, Swanson, Appelbaum, Swartz, Ferron and Van Dorn38

Hamann et al (2011) Reference Hamann, Mendel, Meier, Asani, Pausch and Leucht49 |

442 | Change in capacity scores |

SDM improved capacity in one trial, but not in the other |

Low (−1 risk of bias, −1 inconsistency) |

| Metacognitive training (1 study) |

Naughton et al (2012) Reference Naughton, Nulty, Abidin, Davoren, O'Dwyer and Kennedy15 | 19 | Change in capacity scores |

MCT associated with improved capacity scores |

Low (−1 risk of bias, −2 imprecision, +1 large effects) |

MCT, metacognitive training; SDM, shared decision-making.

Meta-analysis

Psychotic symptoms

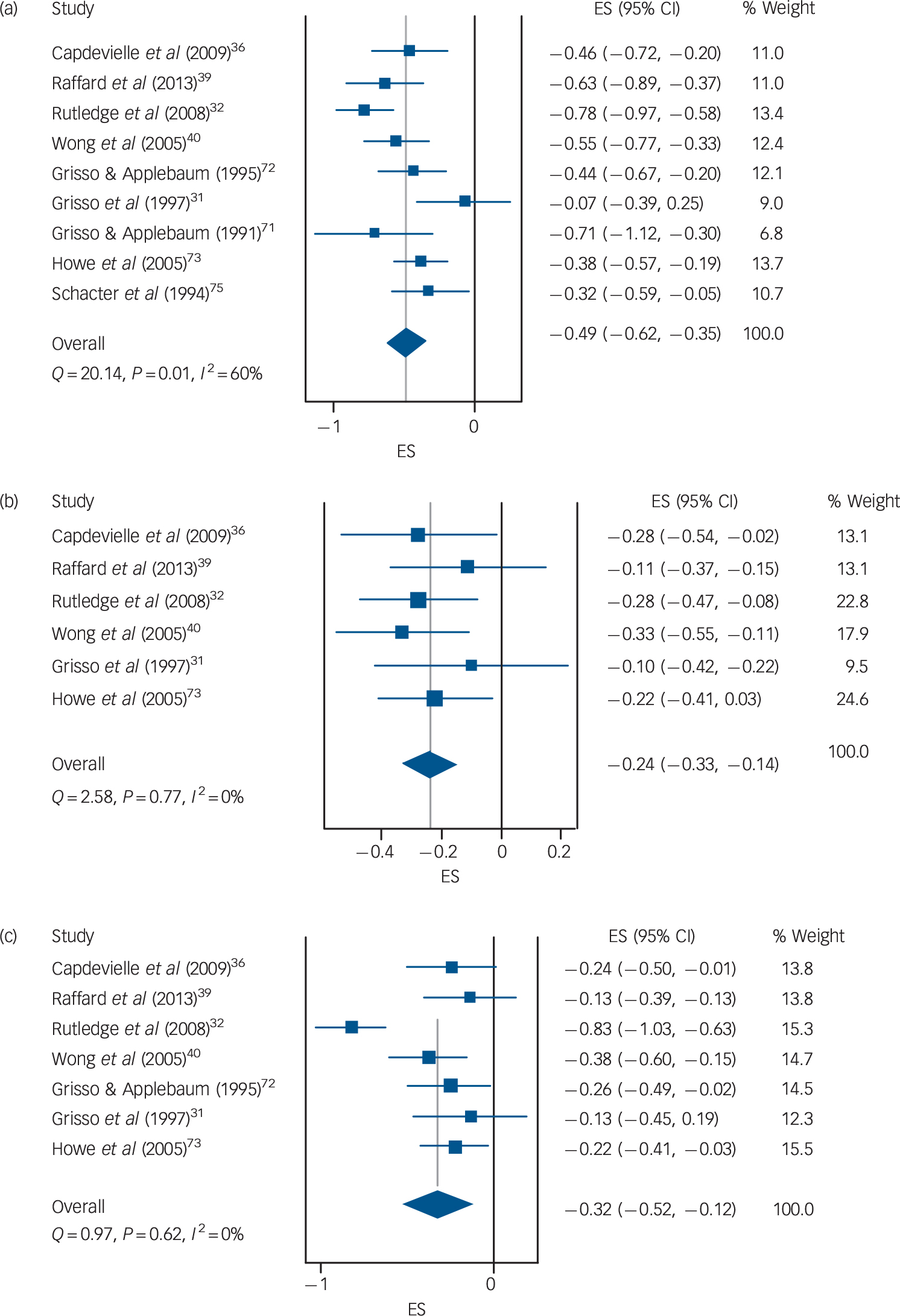

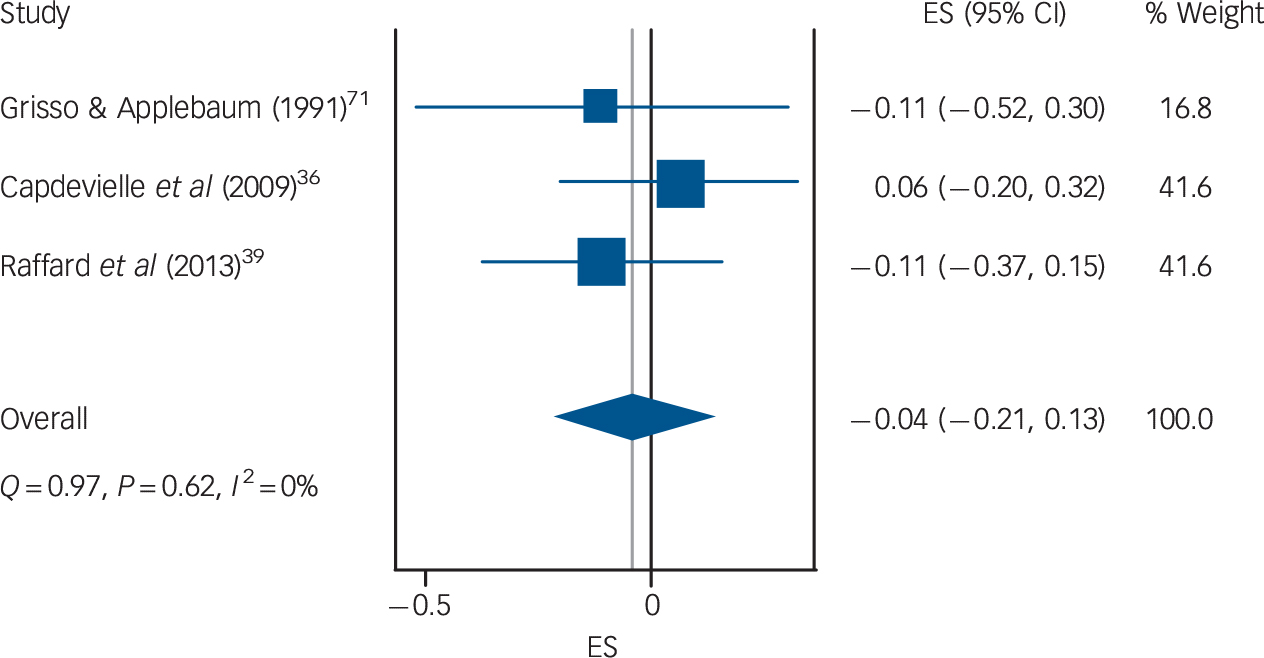

As shown in Fig. 2, pooled data from nine studies (n = 610) suggested there was a moderate to large negative association between total psychotic symptom severity, as assessed by total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores, and the capacity of participants to understand information relevant to treatment decisions (r = −0.45, 95% CI −0.55 to −0.34; I 2 = 60%, moderate quality evidence). All studies reported a negative correlation between symptom severity and understanding, although one reported a considerably smaller effect size. Reference Grisso, Appelbaum and Hill-Fotouhi31 Removing this led to a slightly larger correlation and lower heterogeneity (r = −0.49, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.56; I 2 = 46%). Data from six studies (n = 453) suggested there was a small correlation between overall symptoms and the ability of participants to appreciate information relevant to a treatment decision (r = −0.23, 95% CI −0.14 to −0.32; I 2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence). According to data from seven studies (n = 528) there was a moderate correlation between total symptoms and the ability of participants to reason in relation to treatment decision-making (r = −0.31, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.12; I 2 = 80%), but the quality of the evidence was judged to be low because of risk of bias and high heterogeneity. This high heterogeneity appeared to be attributable to the large correlation reported by a study of a forensic in-patient sample; Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy32 removing this study removed the heterogeneity and also lowered the effect size (r = −0.24, 95% CI −0.33 to −0.14; I 2 = 0%).

Fig. 2 Association between total symptoms and (a) understanding; (b) appreciation; (c) reasoning. ES, effect size.

Depression

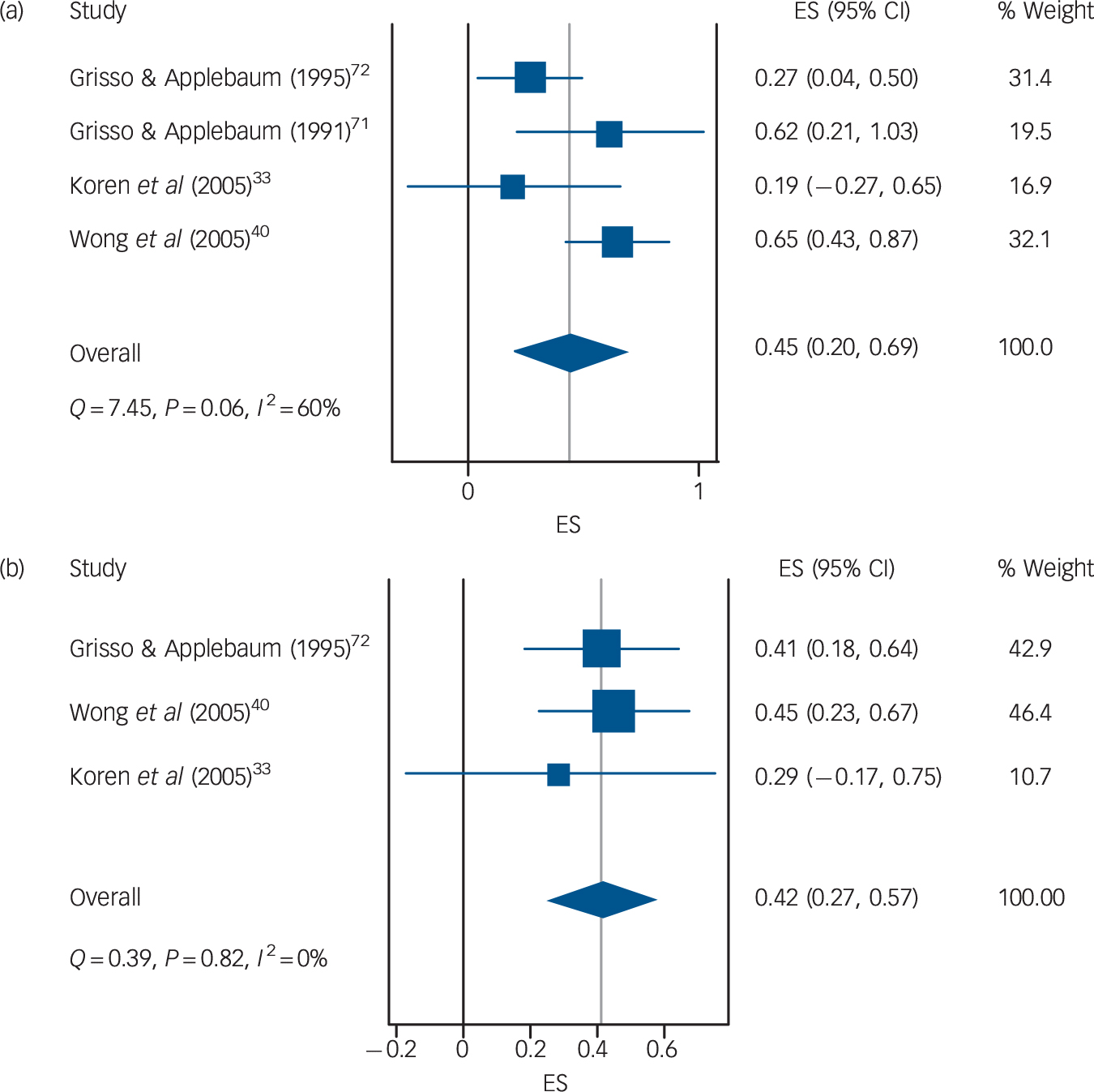

There was no evidence that depression was associated with the ability of participants to understand information about their treatment (Fig. 3; k = 3, n = 146; r = −0.04, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.13, I 2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence).

Fig. 3 Association between depression and understanding. ES, effect size.

Cognitive and intellectual performance

Moderate to large associations were observed (Fig. 4) between verbal cognitive functioning (assessed using subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) and the ability of participants to understand information relating to treatment decision-making (k = 4, n = 203; r = 0.42, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60; I 2 = 60%; low quality evidence) and to use reasoning (k = 3, n = 177; r = 0.39, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.51; I 2 = 0%; low quality evidence).

Fig. 4 Association between verbal IQ score and (a) understanding; (b) reasoning. ES, effect size.

Education

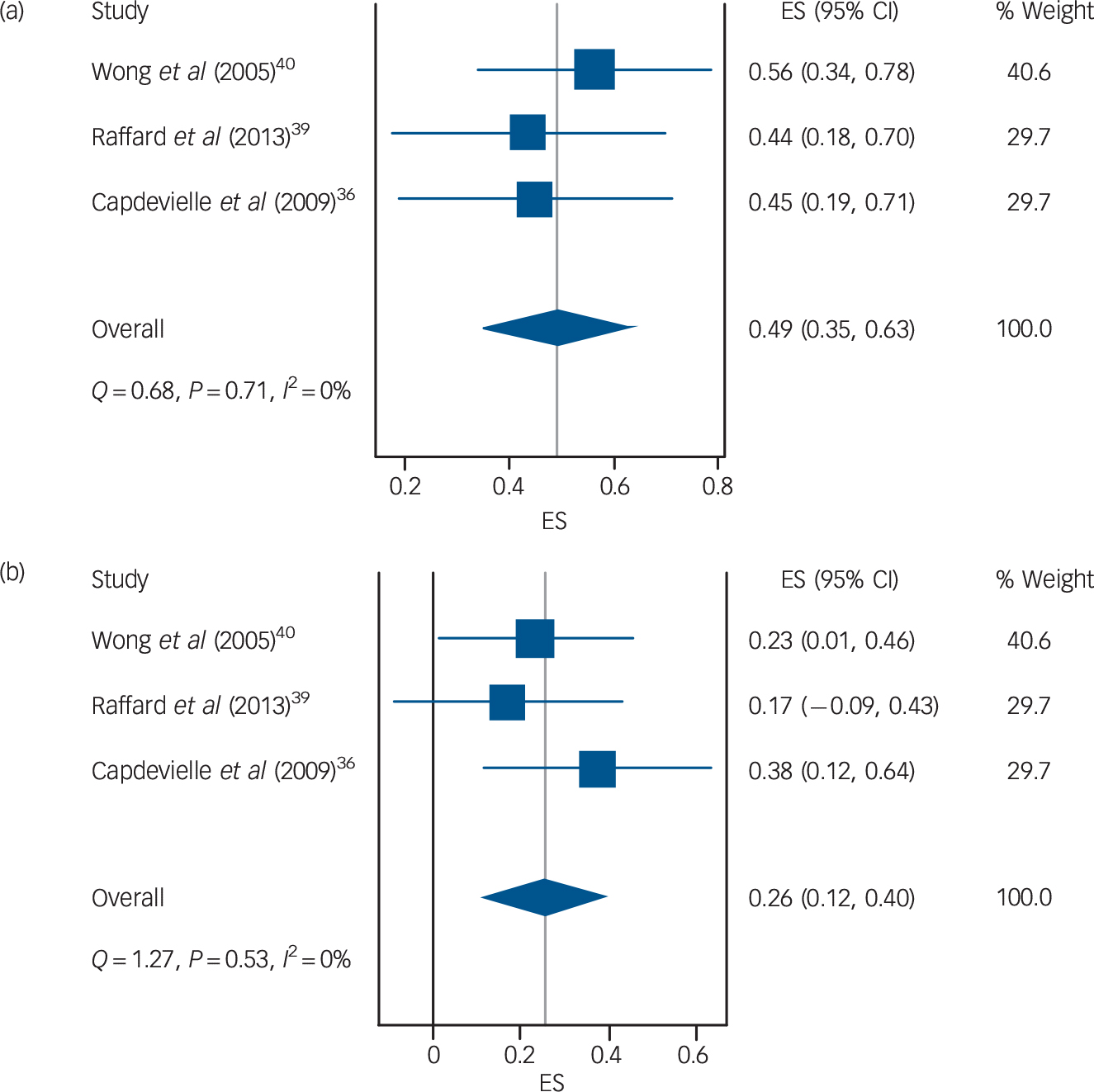

Moderate-quality evidence suggested a large association between years spent in education and the ability of participants to understand information relating to treatment decisions (Fig. 5; k = 3, n = 201; r = 0.46, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.56; I 2 = 0%). The association between years of education and participants' reasoning ability was small to moderate (k = 3, n = 201; r = 0.26, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.38; I 2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence).

Fig. 5 Association between years of education and (a) understanding; (b) reasoning. ES, effect size.

Outcomes from individual studies

A full description of the results of individual studies is provided in online supplement DS6.

Executive functioning

One small study reported non-significant moderate correlations between domains of capacity and aspects of executive functioning, Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33 whereas another reported large reductions in capacity in those with poor executive functioning. Reference Mandarelli, Parmigiani, Tarsitani, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti34

Insight

Five studies assessed the relationship between capacity and different aspects of insight, Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson35–Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 and generally found large reductions in capacity in those with poor insight. One of these studies used the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale, Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 and found much smaller and generally non-significant associations between capacity and self-certainty and self-reflectiveness, with the exception of reasoning and appreciation, which both had moderate positive correlations with self-reflectiveness (reasoning: r = 0.43, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.62; appreciation: r = 0.33, 95% 0.08 to 0.54;). Overall we judged the evidence on insight to be of moderate quality and consistent with the view that insight is associated with improved capacity, in particular reasoning ability.

Duration of illness

Two studies provided low-quality data on the relationship between duration of illness and capacity. Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39,Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40 One did not find a relationship, Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 whereas the other reported a small yet significant relationship with understanding (r = −0.24, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.44). Reference Wong, Cheung and Chen40

Metacognitive ability

One very small study found metacognitive ability was significantly associated with the understanding domain of capacity (r = 0.60, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.82). Reference Koren, Poyurovsky, Seidman, Goldsmith, Wenger and Klein33

Perceived coercion

Moderate-quality evidence from one study suggested that participants without capacity reported higher levels of perceived coercion (Mann–Whitney U = 422.5, P < 0.001). Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson35

Anxiety

Moderate-quality evidence from two studies suggested state and trait anxiety might be positively associated with aspects of capacity, i.e. greater anxiety was linked to greater treatment decisional capacity. Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36,Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39

Interventions

Of the ten intervention studies we identified, five assessed the effect of altering the presentation of information on capacity, two examined the effect of usual treatment, two examined the effect of shared decision-making and one examined the effect of metacognitive training, which is a form of psychological intervention designed to improve a person's awareness of cognitive biases and thinking styles that may be involved in psychotic symptoms. Reference Moritz, Woodward and Balzan41

Presentation of material

Repetition of information, and discussion of presented information with others, were associated with significant large increases in capacity in two studies (d = 1.83, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.18; χ2 = 12.05, P = 0.002), Reference Munetz and Roth42,Reference Palmer, Nayak, Dunn, Appelbaum and Jeste43 whereas a non-significant, small improvement was reported by a third (d = 0.27, 95% CI −0.51 to 1.06). Reference Kleinman, Schachter, Jeffries and Goldhamer44 However, Kennedy et al found that providing extra information to participants in a forensic setting was associated with a significant fell in capacity (d = 0.75, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.20), with a statistically significant proportion of the sample becoming incapable of making a treatment choice following the presentation of extra information. Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy45 Wong et al successively simplified the presentation of information and found that as the task was simplified, capacity improved significantly (Cochran's Q = 14.4, d.f. = 3, P < 0.01). Reference Wong, Clare, Holland, Watson and Gunn46 Overall, the risk of bias across these studies suggested the evidence was of low quality.

Usual treatment

Owen et al found that 37% of patients regained capacity following a month of treatment in hospital. Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Richardson47 Dornan et al found that patients receiving treatment as usual, which included 25 hours per week of individual programmed activities as well as treatment with antipsychotic medications, improved on all domains of capacity: understanding d = 0.62 (95% CI 0.15 to 1.09); appreciation d = 0.39 (95% CI −0.07 to 0.85); reasoning d = 0.63 (95% CI 0.16 to 1.09). Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy48 These authors also found that patients treated with clozapine had significantly larger improvements in appreciation than patients treated with other antipsychotic agents (d = 2.10, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.05), and smaller non-significant improvements were also observed for understanding (d = 0.75, 95% CI −0.09 to 1.59) and reasoning (d = 0.71, 95% CI −0.13 to 1.55). Overall, the evidence for the effect of usual treatment, including antipsychotic medication, was judged to be moderate in quality, with the risk of bias across the studies being mitigated by the large observed effects.

Shared decision-making

Two trials examined the effect of a shared decision-making intervention on capacity. However, these studies found conflicting results, meaning the overall estimate was low in quality. Elbogen et al found a significant effect of shared decision-making on reasoning (F (1,355) = 4.30, P < 0.05) but not on appreciation or understanding, Reference Elbogen, Swanson, Appelbaum, Swartz, Ferron and Van Dorn38 whereas Hamann et al found a non-significant small negative effect on capacity (d = −0.34, 95% CI −0.85 to 0.16). Reference Hamann, Mendel, Meier, Asani, Pausch and Leucht49

Metacognitive training

In a small uncontrolled study, Naughton et al found that patients who received group metacognitive training had significantly improved understanding (d = 1.44, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.45) and reasoning ability (d = 1.21, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.20), but there was no evidence of improvement in appreciation (d = 0.19, 95% CI −0.72 to 1.10). Reference Naughton, Nulty, Abidin, Davoren, O'Dwyer and Kennedy15

Discussion

Our primary objective was to identify which clinical, demographic and intervention-related variables are associated with treatment decision-making capacity in psychosis, and to assess the direction, magnitude and reliability of any relationships. Taken together, our findings suggest that individuals with psychosis are at high risk of being judged to lack capacity if they have spent less time in education, if they disagree with their clinician that they are ill and if they present with severe psychotic symptoms and poor verbal cognitive functioning. Conversely, people with psychosis are more likely to be judged to retain the capacity to make their own decisions if they are relatively well educated, if they demonstrate a reflective ‘metacognitive’ awareness of their difficulties, and if they experience less severe psychotic symptoms or cognitive impairment. Although there is preliminary evidence that heightened anxiety may also be associated with a reduced risk of incapacity in psychosis, depression does not at present seem to be an important factor.

Overall, our review has shown there is promising evidence that treatment decision-making capacity may be responsive to intervention. On the other hand, it has been at least 25 years since the first study of capacity in psychosis, and we still lack robust evidence from randomised controlled trials to know how to support it. Indeed, the absence of high-quality evidence on interventions to improve capacity precludes recommendation of one particular approach. However, we believe that basic standards in ethical and clinical practice dictate that clinicians should endeavour to take a collaborative approach when seeking to support or restore the capacity of their patients, that they should take all reasonable steps to seek their patients' assent for any capacity-supporting interventions they attempt, that any decisions are informed by a thorough assessment and understanding of the specific predisposing and maintaining factors involved in maintaining that person's impaired capacity, and that they use the least invasive (and safest) capacity-supporting interventions available to them. It is likely that interventions meeting this last criterion will include collaborative decision-making and simplification and repetition of decision-relevant information, as well as more complex psychological interventions such as metacognitive training, cognitive remediation and cognitive–behavioural therapy. The latter are relatively ‘tried and tested’ psychological treatments for psychosis, and we know they have beneficial effects on some of the correlates of impaired capacity we have identified – namely symptoms, Reference Turner, van der Gaag, Karyotaki and Cuijpers50,Reference Eichner and Berna51 metacognition, Reference Eichner and Berna51–Reference Cella, Reeder and Wykes53 and cognition. Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor54 Nonetheless, the current absence of direct evidence means that clinicians cannot assume such approaches are effective for supporting capacity, or that they are free from adverse effects. Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy45 For example, it is entirely plausible that improvements in capacity could be accompanied by increased emotional distress, Reference Capdevielle, Raffard, Bayard, Garcia, Baciu and Bouzigues36,Reference Raffard, Fond, Brittner, Bortolon, Macgregor and Boulenger39 perhaps because of increased insight, self-stigma or hopelessness. Reference Belvederi Murri, Respino, Innamorati, Cervetti, Calcagno and Pompili55,Reference Belvederi Murri, Amore, Calcagno, Respino, Marozzi and Masotti56 This uncertainty therefore underlines the importance of clinicians carefully evaluating the success, safety and acceptability of their capacity-supporting interventions.

Study limitations

Some may object to capacity being treated as a continuous variable in the meta-analyses, noting that in legal and clinical practice binary decisions must be made. However, continuous and categorical approaches to classification in psychiatric research and practice are not necessarily mutually exclusive. At this early stage in our understanding of capacity in psychosis, we believe that both approaches can and should be used. Relying only on comparisons between those who have and do not have capacity is problematic for a number of reasons. For example, dichotomising continuous variables is associated with a significant loss of statistical power, equivalent to discarding a third of the data. Reference Altman and Royston57 Dichotomising also masks the fact that people who have borderline impaired capacity may differ much more from someone with severely impaired capacity than they do from someone with borderline intact capacity. Thus, analysing capacity only as a binary construct may lead to incorrect conclusions about the underlying factors that help or hinder capacity.

We originally decided that studies that did not use assessors masked to clinical status when assessing capacity were lower in quality than those that did. However, we acknowledge that this approach does not recognise that real-life judgements of impaired capacity often require clinicians to decide first that a mental disorder is present, and that capacity assessment often involves assessing a person's views on their diagnosis, something which is clearly incompatible with assessor masking. The fact that assessors need to know a diagnosis to perform a thorough capacity assessment does not negate the possibility that such assessments are subject to bias. Without some degree of masking, there remains a significant risk that assessors' beliefs about particular diagnoses may influence the way in which they appraise the values and beliefs of the people they are assessing.

Implications

The concept of capacity was developed partly in response to widespread recognition that status-based tests of competence lack validity. However, there is a concern that capacity has become a simple proxy for insight for many clinicians, Reference Shek, Lyons and Taylor58 thus allowing status-based tests of competence to continue to exert undue influence, albeit in a less obvious way. Reference Allen59 If decisional capacity is to be accepted as a valid proxy for patient autonomy, however, then it must take seriously those definitions of recovery and self-governance advocated by patients, as well as the existence of competing explanatory frameworks. Reference Cooke60 Given that recovery of the ability to self-govern in relation to psychiatric treatment is without doubt an outcome of great importance to many service users with psychosis, further research and analysis in this area is required.

The correlational nature of much of the data in this meta-analysis limits a definitive assessment of causality. Experimental studies conducted within a causal-interventionist framework are now required to develop and test a theoretical model of capacity in psychosis. Reference Kendler and Campbell61 It is also important to consider the wealth of research on cognitive and neuropsychological factors involved in less emotionally salient or ‘real-life’ decision-making – for example, as measured by the Iowa Gambling Task. The development of a comprehensive theory of capacity in psychosis will require integration and synthesis of this literature, but this was outwith the scope of this review.

Future research

Although some researchers have started to adapt and apply more sophisticated non-pharmacological therapeutic approaches to impaired capacity, Reference Naughton, Nulty, Abidin, Davoren, O'Dwyer and Kennedy15 we still lack a good model to inform treatment development. Future research might usefully examine the role of reasoning biases, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington62,Reference Kahneman63 attitudes and beliefs, Reference Armitage and Conner64 emotions such as fear or anxiety, Reference Hartley and Phelps65 and values. Reference Mukherjee and Kable66 The findings of such studies could have important implications for current concepts of decisional capacity in psychosis, and how these interact with the underlying models held by those carrying out capacity assessments – be they primarily social, Reference Selten, van der Ven, Rutten and Cantor-Graae67 psychological, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington62,Reference Morrison68 or biological. Reference Howes and Murray69

Acknowledgements

We thank all those authors who provided additional information about their studies. We would also like to thank anonymous reviewers for their high-quality reviews and helpful comments and suggestions.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.