Whilst recently examining documents contained at the Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive at the Dorset History Centre in Dorchester, I unearthed an item that reveals exciting snapshots of musical life in Vienna during the second half of the eighteenth century. The item is described in the archive's catalogue as ‘a page from a diary in French and Italian (author unknown), dated 1769 “In Vienna”, concerning various acquaintances, as well as various musical works and books’.Footnote 1 Yet this description belies the wealth of musical significance contained in the page's two sides. The solitary slip of paper memorializes powerful, intimate glimpses of ‘off-duty’ conversations held across four months in 1769 between some of the foremost musicians at the Vienna court. In it we hear the voices of Johann Adolf Hasse (1699–1783), Faustina Bordoni (1697–1781), Marianna Martines (1744–1812) and others in their circle, intermingled with the writer's reflections about noteworthy issues both music-related and personal. New and important insights are found into Hasse's nostalgia for Dresden and his musical opinions and prejudices. Fresh information comes to light about Marianna Martines, her musical practices and compositional output. The note also sheds light on the nature of Hasse's tutelage and paints a picture that shows Martines and Bordoni in the roles of mentor and guide. I assert that the purpose of this document and the reason behind its careful preservation were to record impressions and advice stemming from a crucial period in the writer's professional life. The document illustrates a period spent immersed in Vienna's rich musical environment and its crucible of musical learning which, as evidence will reveal, shaped this writer's career as a virtuosa.

The Document and Its Author

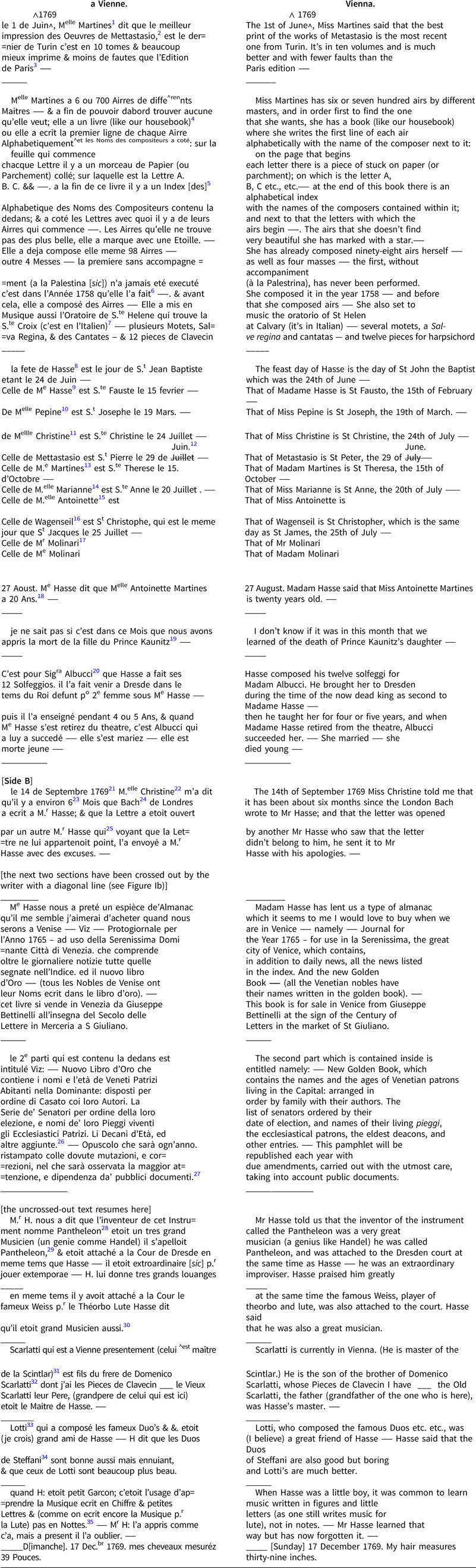

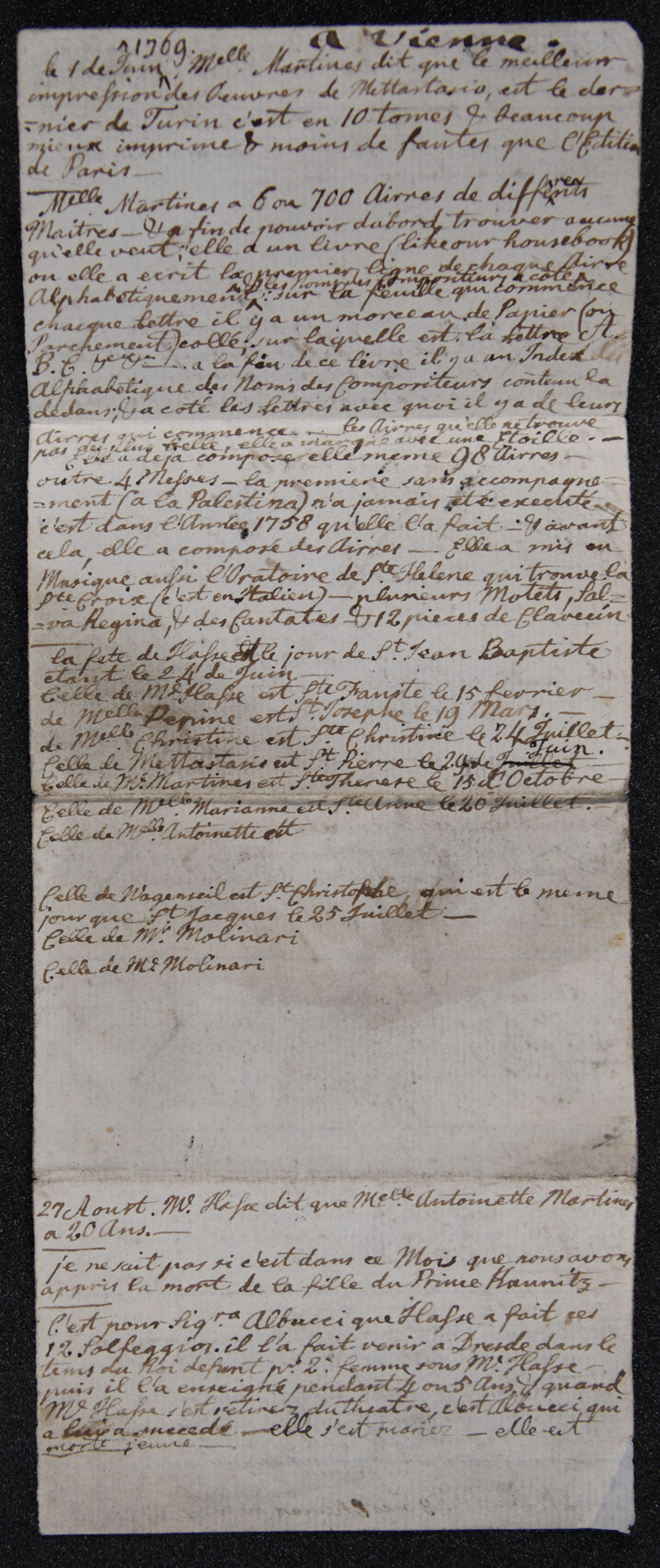

Resting inconspicuously at the very bottom of a tower of account ledgers, shopping lists, life annuities, details of house furnishings, a record of expenses incurred on a trip to Brighton and a recipe for strengthening jelly, the unassuming document is a long and narrow half sheet of paper cut lengthwise measuring 232 millimetres long by 93 millimetres wide. It is densely covered on both sides with small handwriting and folded twice to create four panels on each side of the paper. Material evidence suggests that the sheet was folded before writing on it, which was a common practice at the time.Footnote 2 It carries no indication of watermarks (Figure 1). For ease of discussion, the side of the document beginning ‘le 1 de Juin’ will be referred to as A, and the side beginning ‘le 14 de Septembre’ as B. A diplomatic transcription and my English translation may be found in the Appendix.

Figure 1a. ‘A page from a diary in French and Italian (author unknown), dated 1769 “in Vienna”, concerning various musical acquaintances, as well as various musical works and books’, side A. Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive (D-RAC), Dorset History Centre (GB-DOdhc), D-RAC/H/142. Used by permission

Figure 1b. ‘A page from a diary in French and Italian (author unknown), dated 1769 “in Vienna”, concerning various musical acquaintances, as well as various musical works and books’, side B. Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive (D-RAC), Dorset History Centre (GB-DOdhc), D-RAC/H/142. Used by permission

This study argues that the item is not a ‘page from a diary’, but rather a solitary sheet of notepaper that served as an important aide-mémoire. The page does not offer signs of having been formerly bound as part of a book or diary, and its unusual size supports the notion that this is a loose slip of notepaper. It carries a hurried look as a result of its many corrections, crossings-out and uneven spacing of text, and this conjures up a sense of the urgency with which the information was recorded. The faded brown appearance of the handwriting indicates the use of iron-gall ink, given its propensity to degrade from black to brown over time. Variance in the ink's thickness across the document may be explained by the state of the pen's nib. In a few instances, however, a darker ink can be seen where corrections and insertions have been made. Important among these are the corrected month of Metastasio's name day from July to June (on side A), the year ‘1769’ inserted at the head of side B to anchor the events of 14 September, and the strikingly large words ‘a Vienne’ that situate the memories at the beginning of side A (see Figure 1 and Appendix). Whilst occasional changes in colouration may be a result of varying properties contained in different inks that caused them to fade in an irregular way, it seems most likely that these darker corrections and insertions were added retrospectively. Consequently, the hasty writing style and signs of use do not suggest that this was information copied from another source, such as a diary. Furthermore, the contents of the two sides record events listed beneath four chronological, yet widely spaced, dates spanning a six-month period. The brief time spell it covers and the sparseness of its entries do not suggest that the item is part of a diary.

The Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive within which this document is located is a collection of personal papers belonging to the Reverend Thomas Rackett (1757–1840), his wife Dorothea Tattersall and their daughter Dorothea. As a result of young Dorothea's marriage to Samuel Solly, the collection also contains correspondence of the Solly family. In 1950 a relation of Dorothea Solly, Lieutenant Colonel R. J. N. Solly, gave the collection to the Dorset County Museum. The collection was subsequently transferred to the Dorset History Centre, where it is currently held. As the collection reveals, the Rackett family were immersed in the worlds of culture and science. Residing periodically at their townhouse on King Street in Covent Garden, they were close associates of a London circle of literary and artistic figures that included David Garrick, Samuel Johnson and Giuseppe Baretti. Amongst their musician acquaintances were two English women: Marianne Davies (c1743/1744–buried 1814), a virtuosa of the glass armonica, and her younger sister Cecilia (c1756–1836), a soprano who became known as l'Inglesina. The Davies sisters, as young travelling virtuose chaperoned by their parents, undertook lengthy European concert tours and enjoyed a short residency in Vienna from late 1769 to late 1770. The archive documents their touring career through private correspondence and a fascinating letter-book of introductions written on behalf of the sisters.Footnote 3 As an article by Betty Matthews describes, a plethora of eminent figures contributed introductions, including Empress Maria Theresa (1717–1780), Hasse, Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782) and Pietro Metastasio (1698–1782), helping to facilitate performances at courts and salons across Europe.Footnote 4 The outcome of my investigation into the letter-book's role in constructing a professional network for the Davies sisters is forthcoming.Footnote 5 Their touring came to an end following the deaths of their parents, when, faced with financial ruin, the sisters were forced to return to England. They served as music tutors to the Racketts’ daughter and, as Dorothea Rackett's diary testifies, were regular visitors to the Rackett household, dining with them weekly.Footnote 6

The close relationship between the Racketts and the Davies sisters explains why the musicians’ personal papers ended up in Dorset. The Rackett Family Archive provides a rich source of documentation tracing the family's acquaintance with the Davies sisters. Close examination of this material has presented an array of events and encounters in the lives of the Davies sisters that mirror happenings described on the page's two sides. And it is Marianne who is of particular relevance to the document under consideration here. As a student of her flautist father Richard Davies, she was hailed as a child prodigy of the flute. She performed in London and Dublin from the age of seven as a flautist and harpsichordist who occasionally sang.Footnote 7 As she reached adulthood, prevented from pursuing the flute by prevailing gendered stereotypes, Marianne adopted the new and beguiling glass armonica.Footnote 8

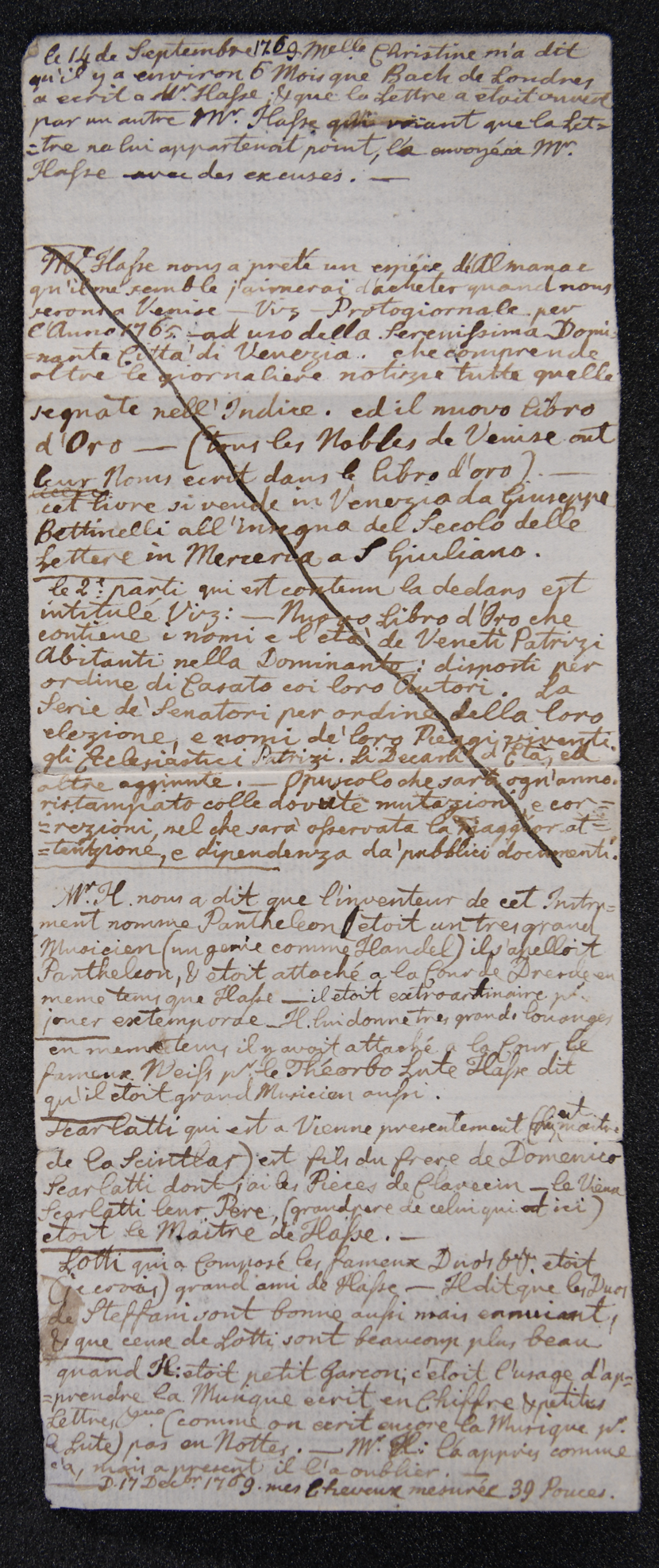

I posit that the author of the document is none other than Marianne Davies. Beyond the connections between the item's contents and the life events of the sisters (discussed below), a comparison of the handwriting with that contained in a personal letter of Marianne Davies reveals striking similarities. The letter is written from Naples to an unspecified ‘Mademoiselle’ on 14 March 1772,Footnote 9 and is thus dated just over two years later than the document. Proud news is conveyed about Cecilia's debut at Naples's Teatro San Carlo under her newly adopted sobriquet l'Inglesina as she replaced prima donna Anna Lucia de Amicis (c1733–1816) in Hasse's Ruggiero. The letter describes at length Cecilia's resilience amidst underhanded attempts to scupper her success by fellow cast members. The contents of the letter suggest that the anonymous ‘Mademoiselle’ was in fact the young Dorothea Rackett. Marianne's close acquaintance with the recipient's mother is reflected in her references to ‘your dear mother’, and her closing wishes of ‘love to Maryann’ seem likely to be intended for Mary Anning, a friend of young Dorothea Rackett.Footnote 10 Marianne also mentions the prospect of retelling her news to a ‘Mrs Sherward’, who may be identified as the mother of Miss Seward, a close acquaintance of the Rackett family.Footnote 11 In her letter, Marianne refers to these people as another part of her true family, one that was well-connected and influential.Footnote 12

Marianne's respect for the Racketts is evident in the look of the private letter, which shows signs of considerable effort in achieving a neat layout, starkly contrasting with the hurried, private aide-mémoire format of the item under discussion. In spite of this, there is a convincing match between many words that feature in both documents. In Figure 2, I have presented the words Hasse, Airre, Lettre, Roi, pas, musique and pouvoir as they appear in each document. The shaping of these words is strikingly consistent. The formation of the upper-case consonants M, P and T as well as the shape of double consonants ss, tt and rr provide a convincing match; so too does the open loop of the lower-case p of pas and pouvoir and the sharp stroke that joins the q to the u in Musique.

Figure 2. A comparison of handwriting using the ‘page from a diary’, Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive, D-RAC/H/142, and private correspondence of Marianne Davies dated 14 March 1772, Rackett Family of Spettisbury Archive, D-RAC/D/79. Used by permission

Nuggets of information scattered across Figure 1 help sketch an image of the author. The document's final note on side B concerns the length of the writer's hair (an impressive thirty-nine inches), confirming that these are the words of a young woman. Meanwhile, early on side A, a sudden, brief lapse from French into English provides another characteristic common to both Figure 1 and Marianne's letter. The author of the document slips into English to describe the book Marianna Martines uses to catalogue her music. The book is ‘like our housebook’, the author explains. Although Irving Godt shows that Martines studied English, English-language proficiency was not widespread in Vienna at the time.Footnote 13 The author's slipping into English indicates that this may have been her native tongue. Marianne's private letter likewise shifts from French into English at points of emphasis, such as the twice-used ‘Dear Mademoiselle’, and when she sends ‘compliments to all friends’ as a closing gesture. It appears that Marianne uses English in both the letter and the document to lend emphasis when writing about more intimate topics relating to family, home or friends. The entry for 14 September 1769 (side B) reveals that the writer is, like Marianne, a keyboard player, as she recalls she owns a copy of Domenico Scarlatti's ‘pieces de Clavecin’.Footnote 14 Marianne was an accomplished keyboardist whose skill was showcased at her earliest performances. At her benefit concert held at Hickford's Great Room on 7 April 1751, Marianne, at the age of seven, played not only a concerto of her own composition on the flute, but also a harpsichord concerto by Handel.Footnote 15 Given her seeming level of ability, it is entirely plausible that Scarlatti's works were part of her personal music collection. Both the handwriting samples and correlating biographical evidence lead me to conclude that this document was written by Marianne Davies and reflects important aspects of her life and career.

Building Connections in Vienna

The double-sided document provides a series of unrelated reflections on different topics, listed chronologically and dated between 1 June and 17 December 1769. A short line inked from the left side of the page separates each entry (see Figure 1). Aside from the faithful copying of a book's Italian title-page and a momentary lapse into English, the document is written in French, the language of polite communication at the time, and probably the language in which these conversations were conducted, as about half a page is filled with reports of music-related talk with Marianna Martines. A quarter of a page is taken up with a kind of aide-mémoire of the name days of Viennese musical figures. Recollections of conversations, both commonplace and music-specific with various members of the Hasse family, take up much of the overall text. The writing is densely packed into a margin-less space that causes occasional cramming of the text at line-ends, which, alongside corrections and insertions of missed words, conjures up the haste with which the memories were preserved. The author's role as re-teller of others’ thoughts and opinions, as a passive observer of or onlooker at these events, gives rise to a sense of subordination, since Marianne often features as the recipient of advice. The tone is tinged with admiration, perhaps awe, as these conversations were swiftly preserved with a hurried hand.

The heavily inked words ‘a Vienne’ and ‘1769’ that open the document on side A give striking emphasis to the top of the page. These words were added later to memorialize the events, anchoring the document in time and place. The deliberate insertion of time and place clearly signals the special significance of this period in the life of its author, a time that marks the pinnacle of Marianne Davies's career. Buoyed by their influential letters of introduction and under the watchful eye of both parents, the Davies sisters had reached Vienna at the end of 1768 following a tour of the Low Countries and Germany. In Vienna, they enjoyed the patronage of Empress Maria Theresa, provided tuition to the Imperial children and performed frequently at court. As Hasse reported in December 1770, ‘these two virtuose have been much distinguished by her Imperial Majesty the Empress, who loved to hear them’ (‘Queste due virtuose sono state molto distinte dalla M. dell'Imperatrice che amava di sentirle’).Footnote 16 The entire Davies entourage lodged with the Hasse family while Hasse, known as Il Sassone (the Saxon), himself tutored the sisters, moulding them into professional virtuose. As a result of their close connection to Hasse, they earned the prestigious title of ‘Saxon Scholars’.Footnote 17

The first entry of the document on side A, dated 1 June 1769, yields particular significance when viewed from the perspective of Marianne's career. On 27 June, both sisters would star as soloists in Hasse's L'Armonica, a cantata set to a libretto by Metastasio to mark the wedding celebrations of Duke Ferdinand of Parma and Archduchess Maria Amalia.Footnote 18 The jottings of 1 June speak first-hand to the musical and social environment in which the Davies sisters were immersed in the run-up to this prestigious event, which marked the highpoint of Marianne's career. The magical effect of their combined sonorities of voice and glass armonica moved Metastasio to such an extent that he continued to praise their abilities some two years later. As he recalled, ‘[Cecilia] has the power of uniting her voice with the sound of the armonica and, almost miraculously, of imitating its tones so exactly, that it is sometimes impossible to distinguish one from the other’ (‘quando accompagna suo canto al suono dall'armonica sa cosi mirabilmente accordar la propria alla voce di quello, che tal volta non è possibile distinguerne la differenza’).Footnote 19

Marianne's residency at the Vienna court provided a rare period of financial stability, to which she would refer later in her career in a desperate letter to Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), the inventor of her instrument. Suffering great financial hardship by 1783, Marianne nostalgically describes an imperial generosity that stretched to the entire Davies family, explaining that the Empress ‘graciously deign'd to Patronize in a most particular manner’.Footnote 20 Marianne's studies with Hasse also gave the Davies sisters access to his Vienna circle. Much of the document's text relates to anecdotes, daily news and musical stories stemming from the Hasse family, and it is easy to imagine that these were the products of evening conversations around the family dining table. The intimacy of the connections the sisters made is vividly illustrated as Marianne collates the names of those gathered in their inner circle alongside their saints’ days. The Hasse family are listed first, followed by Metastasio and the household of Marianna Martines and, finally, other colleagues from the musical world. Some entries are left incomplete, evoking a sense of the busy comings and goings and unpredictable acquaintances that Marianne made in Vienna. The final entries for Monsieur and Madame Molinari trail away unfinished into an unused space of paper, suggesting the writer's anticipation of collating the names of yet more new connections at some point in the future. Certainly, for a fledgling virtuosa seeking to establish herself amongst Vienna's rich musical environment, it would be highly advantageous to have a record of these significant dates relating to new, important and influential acquaintances.

The impact of the Davies sisters’ letters of introduction in securing a professional network that propelled the young women into lengthy European tours cannot be underestimated. Interestingly, reflections on happenings related to two of their recommenders are recorded in the document. A curious story about the re-emergence of a letter from Johann Christian Bach to Hasse that had gone astray is worthy of note. Considering the document alone, it is unclear why a seemingly everyday happenstance relating to undelivered mail should make its way into a written record. However, if one considers that Johann Christian Bach was an important supporter of the Davies family, it perhaps makes more sense. The ‘London Bach’ had already proven his allegiance to the Davies sisters by providing seven letters of introduction to his former Italian patrons ahead of their departure to the Continent.Footnote 21

A mention of the death of Maria Antonia von Kaunitz-Rietberg, daughter of Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg (1711–1794), towards the end of side A of the document reveals other connections. The Davies sisters’ letter-book contains over thirty introductions issued by diplomats. Amongst these two are provided by Prince Wenzel Anton Kaunitz, private advisor to Empress Maria Theresa.Footnote 22 The Davies sisters’ acquaintance with Kaunitz, thanks to an introduction from Count Cobenzl in Brussels, bore fruitful introductions to the influential and musically well-connected ambassadors Count Durazzo in Venice and Count Firmian in Milan ahead of the sisters’ trip to Italy. Through their provision of introductions, diplomats fostered cultural exchange and helped musician visitors to expand their networks. As Mark Ferraguto has highlighted, part of Kaunitz's responsibilities included supporting visiting musicians.Footnote 23 Diplomats like Prince Kaunitz facilitated performance opportunities at their salons for musicians to garner exposure and build networks. For the Davies sisters, Kaunitz thus became an important and influential contact. Such connections could also be personal, even familial. With this in mind, the document's record concerning the recent death of Kaunitz's daughter is suddenly given context and greater significance.

Curiously, Marianne shifts into the past tense here, explaining ‘I don't know if it was in this month that we learned of the death of Prince Kaunitz's daughter’ (‘je ne sait pas si c'est dans ce mois que nous avons appris la mort de la fille du Prince Kaunitz’). The information appears in an entry of 27 August (side A), and this may indicate it was part of a monthly rounding-up of news. There is no visible change in the colour of the ink or in the consistency of handwriting to suggest this particular comment was added any later, but the effect is one of a sudden shift from present to past, from news hurriedly noted in the moment to a retrospective summary of recent events. The document as a whole is characterized by intermittent and chronologically widely spaced entries, and in this particular instance, the August comments constitute the first entry of news since 1 June. The intervening period was particularly intense for the Davies sisters, as noted above, and perhaps this prevented Marianne from recording news updates as they happened, necessitating a reflective summary of recent happenings.

Similar intersections between musicians, diplomats and patrons are recorded in the entry dated 14 September 1769 (side B). An important musical visitor to Vienna is carefully identified as Giuseppe Scarlatti (1712–1777). As the writer explains, he is ‘the son of the brother of Domenico Scarlatti’ and the grandson of ‘Scarlatti the father [who] was Hasse's master’ (‘Scarlatti qui est a Vienne presentement . . . est fils du frère de Domenico Scarlatti . . . le Vieux Scarlatti leur Pere, (grandpere de celui qui est ici) etoit le Maitre de Hasse’). This record of Giuseppe Scarlatti's presence in the city supports Gordana Lazarevich's assertion that he was active in Vienna from c1757 until his death in 1777.Footnote 24 Interestingly, the networks of Giuseppe Scarlatti and the Davies sisters had intersected during this period by means of shared influential contacts. Scarlatti had enjoyed the patronage of both Gluck and Count Durazzo.Footnote 25 Durazzo (1717–1794) had been a strong supporter of Gluck's operatic reforms, but, when his efforts began to jar with the Imperial court, he was sent to Venice in the role of diplomat. Gluck, to whom the girls carried a letter from a Sir Le Noble in Schwetzingen dated July 1768, may well have facilitated their introduction at the Viennese court. When the Davies family moved onwards to pursue musical adventures in Italy at the close of 1770, Prince Kaunitz and a Countess Questenberg provided them with letters of introduction to Count Durazzo. As Ferraguto has also pointed out, Durazzo was an influential figure in the sphere of music, whose role as diplomat involved bringing the best musicians and singers to Venice at the behest of Emperor Joseph II.Footnote 26 Durazzo consequently propagated the expansion of the Davies sisters’ circle of acquaintance by introducing them to Count Pallavicini in Bologna in June 1771.

Tutelage under Hasse and Bordoni

Since a well-connected teacher could make a career, the relationship between pupil and teacher was of utmost importance. The document reveals important information about Marianne Davies's experiences with her teacher Hasse and his wife, the singer Faustina Bordoni. The pair played an important role in educating Marianne, both musically and professionally.

Bordoni seems to have taken a particular interest in assisting the sisters in developing their patronage network, evidenced by the fact that Bordoni loaned the sisters a valuable book. Curiously, the careful detailing of the Libro d'Oro, a volume that lists all the noble patrons of Venice for the year 1765, takes up considerable space on side B.Footnote 27 Its lengthy description is indicative of its importance and usefulness to Marianne. The Libro d'Oro provided an indispensable networking tool for the self-supporting virtuosa in Venice. The complete title is faithfully copied in Italian along with the address of where it might be purchased. The writer notes that she has borrowed the book from ‘Madame Hasse’, though the volume holds such invaluable potential that she notes she ‘would love to buy [it] when we are in Venice’. It is not inconceivable that a discussion about making connections prompted Bordoni to lend her copy of the Libro d'Oro to Marianne. In any case, this remark confirms both the investment value of a directory of patrons and a pending visit to Venice. Just a year after the document was written, the Davies family departed Vienna and moved onwards in search of success in Italy. Venice was indeed their first destination, bolstered by five letters of introduction to important contacts at this musically competitive and challenging hub.Footnote 28 That the section relating to the book was subsequently crossed out might suggest that Marianne did find her own copy in Venice.

The broad scope of Hasse's tutelage is revealed in the document. His guidance encompasses the relating of important anecdotes about his musical past, specifics about his own musical development and impressive details concerning his connections. Marianne records a conversation about the composer's musical environment at the Dresden court. The Hasse family were forced to leave Dresden against their will owing to the Prussian occupation of the city in 1756. Hasse described their departure as having taken place in ‘a high state of confusion’.Footnote 29 The subsequent bombardment of Dresden, in 1760, destroyed a place to which the composer never returned. With this in mind, one might imagine that his comments evoke a personal nostalgia for his time in the city. Hasse was seventy at the time the document was written, and he reminisces about working with esteemed colleagues who were, by 1769, no longer living. In this way, Hasse can be seen as an important and influential thread whose anecdotes link the musical world of the past to the future, through the young Davies sisters.

As a skilled keyboardist, Marianne Davies would surely have been intrigued to hear Hasse describe how he was taught to read keyboard notation. Hasse explains that as ‘a little boy, it was common to learn music written in figures and little letters (as one still writes music for the lute), not in notes’ (‘quand H: etoit petit Garcon; c'etoit l'usage d'apprendre la Musique ecrit en Chiffre & petites Lettres & (comme on ecrit encore la Musique p.r la Lute) pas en Nottes’). The method of notating music that Hasse describes appears to be a form of keyboard tablature, which took different forms during its use from about the fifteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century. Pieter Dirksen distinguishes between a Spanish form of tablature that involves the use of numbers and a separate form that existed in Germany. He explains: ‘in Germany, in the course of the sixteenth century, people took the opposite approach and wrote everything in letters, and this is what is usually understood today by (German) organ tablature’ (‘koos men in duitsland in de loop van de zestiende eeuw de tegenovergestelde weg en schreef alles met letters, en dit is wat men tegenwoordig gewoonlijjk onder (Duitse) orgeltablatuur verstaat’).Footnote 30 Given that the note recalls notation that involves both numbers and letters, this may suggest that Hasse was familiar with both styles.Footnote 31 The practice of keyboard tablature was diminishing by the time of J. C. Bach (and therefore by the time of Marianne's birth). Furthermore, it appears that, unlike lute tablature, keyboard tablature was an uncommon form of notation in England. Changes in musical practices across generations coupled with the scarce usage of tablature in England might explain Marianne's unfamiliarity with the method. Indeed, her note appears to suggest she may, out of curiosity, have asked Hasse to demonstrate the practice, as she records that he ‘learnt that way but has now forgotten it’ (‘Mr H: l'a appris comme c'a, mais a present il l'a oublier’). The tablature conversation once more forges a link between music's past and present.

Hasse brings the importance of Dresden's lutenist and theorbo player Silvius Leopold Weiss (1686–1750) into the spotlight. The Hasse and Weiss families had been close; Johann and Faustina were godparents to the Weiss's son Johann Adolf Faustinus. In relating his Dresden musical history to the author, Hasse singles out Weiss as being ‘also a great musician’ (‘il etoit grand Musicien aussi’). Indeed, by 1744 Weiss's significance at the Dresden court was clearly reflected in his elevated position as its highest-paid instrumentalist.Footnote 32

It appears that Hasse taught good musical taste through recollections of his musical past. In the document, he compares the duos of Antonio Lotti (1667–1740) with those of Agostino Steffani (1654–1728), presumably Lotti's Duetti, terzetti e madrigali a più voci, Op. 1 (Venice, 1705), and Steffani's chamber duets thought by Colin Timms to have been composed by late 1702.Footnote 33 Hasse impressed upon the young listener that ‘the Duos of Steffani are also good, but boring, and Lotti's are much better’ (‘H. dit que les Duos de Steffani sont bonne aussi mais ennuiant, & que ceux de Lotti sont beaucoup plus beau’). Certainly Hasse's preference for his friend Lotti's compositions stated here tallies with Burney's account that ‘Hasse is said to have regarded [Lotti's] compositions as the most perfect of their kind’.Footnote 34

Despite the training that Hasse gave to the sisters, however, he had his concerns. In recounting his musical past, Hasse praises two Dresden musicians whose strengths curiously counter the sisters’ shortcomings. Marianne first records Hasse lauding prima donna Teresa Albuzzi Todeschini (1723–1760), for whom, she explains, he composed his Solfeggi, a work intended as a pedagogical tool. Hasse points out that Albuzzi was under his guidance for some four or five years, in other words more than twice as long as Cecilia. Furthermore, he praises the superior musicianship of Pantaleone Hebenstreit (1668–1750), declaring him to be ‘a genius like Handel’ (‘un genie comme Handel’). The impact of this comment is twofold. First, it indicates the reverence in which Hasse held Handel, who had died in 1759, using him as a yardstick against which to measure the musical merit of his colleagues, and simultaneously attaches a sudden musical significance to Pantaleone Hebenstreit. Second, it casts a new light on the extent of Hebenstreit's skill and evokes a sense of the professional respect he garnered from his contemporaries. Hebenstreit's pantaleon, an instrument of his invention similar to a hammered dulcimer, produced a beguiling tone just like Marianne's glass armonica, and this shared timbral connection may have provoked Hasse's recollection. Hasse stresses that Pantaleone ‘was an extraordinary improviser’ (‘il etoit extroardinaire [sic] p[our] jouer extemporae’). The composer uses this recollection to pinpoint precisely an ability that he felt Marianne lacked, as we shall see.

Amongst their letters of introduction to noble Venetians, Hasse had supplied the sisters with an introduction to his long-time correspondent, the influential Giammaria Ortes (1713–1790). It is through the surrounding exchange of private correspondence between the two men that Hasse's opinion of the sisters becomes clear. His tutelage of the young women was brief, and the responsibility this brought – particularly in nurturing Cecilia into a leading soprano in this short time – becomes apparent in his correspondence. As their impending departure from Vienna grew closer, he began to distance himself through reservations transmitted in private to Ortes. Hasse stressed the brevity of their studies, explaining that Cecilia was not yet ready for an Italian audience, not least because her Italian remained a horrible stumbling-block.Footnote 35

Hasse's misgivings about Cecilia's readiness for an Italian audience might be understandable given her young age of just thirteen. Marianne, however, had considerable performance experience behind her, and had already made an impression on her audiences. During her Paris debut in 1765, her technical skill and musicianship were praised in an article about the ‘harmonica’ that appeared in the July edition of the Journal des Dames. The journal reported that

Mademoiselle Davies . . . paroît très propre à donner de la célébrité à cet instrument par l'habileté avec laquelle elle en joue . . . Mademoiselle Davies en joue avec beaucoup d'art, & comme Musicienne, elle est peut-être encore plus merveilleuse que son instrument. On a applaudi sur-toue à l'expression avec laquelle elle joue le beau morceau de Castor & Pollus: séjour de l’éternelle paix. Tous les Spectateurs en sont attendris, & il s'en faut de peu qu'elle ne leur arrache des larmes.Footnote 36

Miss Davies . . . seems very well suited to make this instrument famous by the skill with which she plays it . . . Miss Davies plays it with great artistry, and as a musician she is perhaps even more marvellous than her instrument. We applauded above all the expression with which she played the beautiful piece from Castor et Pollux, ‘Séjour de l’éternelle paix’. All the listeners were touched by it, and it nearly brought them to tears.

Amongst Marianne's audience at the Hôtel d'Angleterre, her second Parisian venue, was music critic Albrecht Ludwig Friedrich Meister (1724–1788). A year later, whilst describing the armonica to German readers, he explained that ‘Ein englisches Frauenzimmer, die Jungfer Davies, . . . soll noch zur Zeit die einzige Person sein, die es in gehöriger Vollkommenheit zu spielen weiss’ (an English lady, the young Davies, . . . is said to be the only person who knows how to play it with due perfection).Footnote 37 In spite of the reputation Marianne had clearly achieved before reaching Vienna, Hasse questioned her ability, explaining that, although she played well enough, she needed to work on her improvisatory skills and her ability to play good music by heart (‘Per suonarlo bene assai, bisognerebbe lavorare di fantasia, ed avere buona musica in testa’).Footnote 38 Fearful of a potential professional disaster for the sisters that might reflect badly upon him, Hasse forewarned Ortes, ‘if they keep in their heads everything I have said, and they remember everything, all that I've said and repeated a thousand times, I hope it won't go badly’ (‘Se tuttavia si tiene sul piano che le ho dato, e se si ricorda di tutto quello, che mille volte le ho dette e ridetto, spere, che le cose non anderanno male’).Footnote 39 One might view this unique document as Marianne's attempt to keep Hasse's lessons in her head. And, given Hasse's concerns as expressed to Ortes, might we not see his references to Albuzzi and Hebenstreit as a way of reminding two headstrong young women that there was still work to be done?

Meeting Marianna Martines

For two young, aspiring virtuose, the Davies sisters’ residency in Vienna provided not only an opportunity for study with Il Sassone and immersion into his rich musical circle, but also rare opportunities to observe and interact with successful female musicians. Lodging with the Hasse family, the sisters found themselves in close proximity to legendary prima donna Faustina Bordoni and to Marianna Martines, a fact which has hitherto escaped scholarly notice. If my assertion that Marianne Davies is the writer of this document is correct, new evidence emerges of a meeting between these two young professional virtuose.

Half of one side of the document is devoted to an encounter with Martines, recording in minute detail her advice, compositional practices and a list of her works (see Figure 1a). Just like the Libro d'Oro, the significant amount of space devoted to this subject indicates the impact the meeting had upon Marianne. Every aspect of the conversation is recorded with such attention to detail that it appears as though its author looked up to Martines as a role model.

As the protégée of Pietro Metastasio, Martines was well placed to offer Davies her advice on the best available edition of his works. That Metastasio featured in their conversation recorded on 1 June may well be testament to his significant presence in Marianne Davies's life during that period. The days that followed marked the run-up to the performance by the Davies sisters on 27 June of the Hasse–Metastasio collaboration L'Armonica before an eminent and prestigious audience.

The entry provides enlightening further information regarding Martines’ music collection and compositions. Irving Godt has noted that Martines ‘amassed a large collection of music – her own and that of her contemporaries and predecessors’.Footnote 40 However, he continues, the collection ‘was dispersed, in a process that began even before the composer's death’.Footnote 41 The document affirms that Martines possessed an extensive collection of vocal music that included ‘six or seven hundred Airs by different Masters’ (‘Melle Martines a 6 ou 700 Airres de differents Maitres’). Marianne pays particular attention to Martines’ method of alphabetically cataloguing her airs and the way she distinguishes her least favourite airs with a star.

Marianne lapses into English as she describes the book, a feature she appeared to employ when, as noted above, there was an emphasis on intimate, familial matters. The comment that Martines's book is ‘like our housebook’ simultaneously reveals that Marianne Davies and her family possessed their own music collection and indicates that the Davies sisters may well have been experienced in copying manuscripts. Furthermore, the document reveals that their collection was catalogued using some form of alphabetical system. Margaret R. Butler has uncovered valuable material relating to a music collection belonging to Cecilia Davies: twenty-four items taken from Italian operas contained in the Frank V. de Bellis Collection at the San Francisco State University Library. She refers to these items as the ‘Davies Collection’ and acknowledges that they are just a portion of a ‘large and unified corpus of extant music and literary material’ belonging to Cecilia.Footnote 42 Amongst the items under her investigation are examples of manuscripts that carry a large capital letter at the top of the page, denoting the first letter of the first word with which the text of an aria or recitative begins. Butler posits that the capital letters were the later annotations of the Davies sisters’ student and former custodian of the manuscripts, Dorothea Solly.

This assertion is reached via a comparison of capital letters appearing in the music manuscripts with the handwriting of a note by Solly contained in the Folger Shakespeare Library.Footnote 43 According to Butler, ‘Solly evidently lent considerable attention to labelling and organising the individual manuscripts and librettos that eventually became part of the de Bellis material . . . She labelled the librettos with Davies's name, and affixed capital letters to the top of the first page of many of the Italian pieces. The letters correspond to the first word of text in the piece’.Footnote 44

However, if we recall Marianne's comments in the document, Solly's authorship of the capital letters in Butler's Davies Collection is thrown open to conjecture: Marianne describes Martines's alphabetical system of cataloguing music where she ‘writes the first line of each air alphabetically with the name of the composer next to it: on the page that begins each letter there is a piece of stuck-on paper (or parchment) on which is the letter A, B, C etc.’ (‘elle a ecrit la premier ligne de chaque Airre Alphabetiquement et les Noms des compositeurs a coté: sur la feuille qui commence chacque Lettre il y a un morceau de Papier (ou Parchement) collé; sur laquelle est la Lettre A. B. C. && –––’). Marianne reflects, as if to add a clarifying memory tag for future use, that this method is ‘like our housebook’, thus revealing that the alphabetical system was one she and her family used. This raises the inevitable question whether Butler's alphabetically arranged pages are in fact annotated with capital letters not in the hand of Solly, but in the hand or hands of Marianne and her family, and, further, that these pages were perhaps formerly part of the Davies sisters’ housebook.Footnote 45

Anton Schmid, curator of the Vienna court library, provides the most accurate account of Martines's oeuvre in his 1846 biographical publication.Footnote 46 As Godt explains, ‘Schmid's work list, if at all accurate, suggests that much of her instrumental music and her works for solo voice are lost, or at least unaccounted for’.Footnote 47 Marianne Davies records that Martines ‘has already composed 98 airs herself as well as 4 masses. The first, without accompaniment (à la Palestrina), has never yet been performed. She composed it in the year 1758, and before that she composed airs’ (‘Elle a deja compose elle meme 98 Airres outre 4 Messes la premiere sans accompagnement (a la Palestina [sic]) n'a jamais eté executé c'est dans l'Année 1758 qu'elle l'a fait’). This comment imparts new information that contextualizes and quantifies Martines's vocal output. Schmid's list records 156 arias, out of which, Godt notes, just twenty-seven survive.Footnote 48 Thus we can deduce from the document that over half of Martines's arias belong to her early works.Footnote 49 Marianne continues that Martines's first mass was composed in 1758. With this nugget of information, Godt's suspicion that the Mass in C major was composed earlier than 1760 is helpfully confirmed; we can now say with confidence that it was finished in 1758.Footnote 50 Marianne's observation that the composition of airs preceded Martines's first mass might be perceived as a sort of tip on how to go about large-scale vocal composition. The progression seemed to have been successful for Martines, for the document further confirms that by June 1769, Martines had already composed ‘several motets, a Salve regina and cantatas, and twelve pieces for harpsichord’ (‘Elle a mis en Musique aussi . . . plusieurs Motets, Salva Regina, & des Cantates & 12 pieces de Clavecin’). This remark helpfully pinpoints the compositional period of Martines's Salve regina, which is recorded ‘date unknown’ in Godt's list.Footnote 51 Further, the ‘12 pieces de Clavecin’ may relate to a small portion of the thirty-one sonatas by Martines that were recorded by Schmid. It is not inconceivable that the three surviving sonatas listed by Godt that are dated c1762 or before and c1765 stem from this collection.Footnote 52 Marianne also notes that Martines had already completed the oratorio Sant'Elena al Calvario to a text by Metastasio (‘Elle a mis en Musique aussi l'Oratoire de S.te Helene qui trouve la S.te Croix (c'est en l'Italien)’). This comment consequently narrows the oratorio's possible compositional date to before 1769, more than a decade earlier than Godt's suggestion of around 1781.Footnote 53

I suggest that the document records the outcomes of one or more conversations. If my suspicion is correct, this marks a fascinating and hitherto unknown acquaintance between Marianne and Martines, two virtuose of similar age who had earned fame as child prodigies. Their pathways to success, however, were starkly different. As Rebecca Cypess explains, Martines attributed her distinguished musical abilities to a combination of natural gifts and diligent personal application.Footnote 54 During her formative years, the Altes Michaelerhaus provided a home to Haydn and Porpora, who appear to have contributed to her musical education.Footnote 55 Pietro Metastasio, however, provided her with long-term mentorship and professional guidance. Appointed Poet Laureate in 1730, Metastasio took lodgings on the third floor of the Altes Michaelerhaus, residing not only in the same building, but in the same apartments as the Martines family.Footnote 56 The close proximity of their living quarters surely contributed to the particular nature of their relationship. In a letter to Padre Martini, Martines describes the ‘paternal care’ that Metastasio showed to her and her family, whilst Schmid's biography of Martines explains that Metastasio provided ‘rearing and education with all the warmth of a careful father’.Footnote 57

Tutelage under Metastasio afforded access to his professional network and contacts, including those at the Imperial court.Footnote 58 The impact of the knighthoods granted to the brothers of Marianna Martines from 1774 elevated the social standing of the family and strengthened their connections to the court.Footnote 59 Martines practised subtle self-promotion, defining herself not as a member of the professional class of musicians but as a dilettante. She carefully portrayed herself not as a musician striving to earn a living through their work, but as someone whose musical activities were carried out simply for pleasure. By adopting the role of dilettante and through her performance at her own salons, Martines occupied a powerful ‘liminal space . . . situated between the public and private spheres, rather than in full view of the public eye’.Footnote 60 Thus her musical accomplishments were carried out ‘behind a veil of upper-class respectability’.Footnote 61 By contrast, Marianne Davies was born into the professional class of musicians. Her childhood was characterized by the nomadic life of the freelance musician, touring England and Ireland performing in concert series and benefit concerts, and providing musical interludes in long theatrical runs. Her father, an established flautist and freelancer on the London stage, tutored her; his colleagues from the Italian opera often bolstered her concerts, a musical world that Marianne had become immersed in from an early age.Footnote 62

The encounter between these two young accomplished virtuose may provide a hitherto undocumented example illustrating Martines's support for her female contemporaries. It appears to reinforce the notion that Martines demonstrated a nurturing and encouraging attitude towards her female colleagues, rather than regarding them as threatening rivals, as in fact Godt suggests.Footnote 63 Godt has asserted that the young professional musician Maria Rosa Coccia, who sent some of her works to Metastasio for his approval, was a potential rival to Martines. Cypess, though, counters this notion by highlighting Martines's elevated social position as a dilettante, a position that enabled her to rise above any sense of rivalry or threat and instead react with encouragement. Furthermore, Cypess points to the impact of Martines's musical salons and her vocal studio as evidence of her nurturing and supportive role towards women. These two areas of activity allowed Martines to demonstrate her ‘interests in music as a source of edification and the fostering of musicianship in other women’.Footnote 64 It is indeed plausible that the encounter between Martines and Marianne took place at one of Martines's Akademien.Footnote 65 In any case, Marianne was plunged into a new, eye-opening musical world in Vienna, one that fostered an established and highly regarded female contemporary who surely served as an influential role model to the young Miss Davies.

Conclusion

The document examined here provides new information about musical life and everyday happenings across six months spent in Vienna in 1769. Bringing to light the musical opinions and prejudices of Johann Adolf Hasse and offering insights into his teaching methods, it also reveals glimpses of the professional guidance and mentorship provided by the soprano Faustina Bordoni towards a young virtuosa. The document further provides an image of the working practices of Marianna Martines and uncovers new data relating to her output and the chronology of her compositions. In addition, it appears to show Martines's support for and encouragement towards another young female musician. The document presents a series of events and encounters that correspond strikingly with known happenings in the lives of the Davies sisters, who were present in Vienna at this time, lodging with the Hasse family. During the period of the page's creation, Marianne and Cecilia Davies were engaged to perform for an imperial wedding and gave frequent performances before the Empress herself, yet their names are not mentioned. The identification of Marianne Davies as author of the document can be supported further by similarities in handwriting styles between it and Marianne's private letter, written just over two years later.

The value of this document is particularly high because it appears to show the evolution and shaping of a young female musician's career; it reconstructs the musical environment in which this educational process took place, illustrating the influential contacts she encountered, the role models she looked to and the stories and advice that she saw fit to note down. It reveals the development of her networking practices and highlights their central role in sustaining a career and courting patronage. And, despite its ephemerality, I contend that this document was not created or preserved by accident. Rather, it was specifically intended to protect precious musical memories and events that marked the pinnacle of a career, to ‘keep in her head’ everything Hasse said during this important period of musical development. At the same time, it provides an intimate image of the eighteenth-century virtuosa Marianne Davies.

APPENDIX

‘A page from a diary in French and Italian (author unknown), dated 1769 “in Vienna”, concerning various musical acquaintances, as well as various musical works and books’