Breast-feeding is crucial for the healthy growth and development of the child( Reference Ip, Chung and Raman 1 , Reference Ladomenou, Moschandreas and Kafatos 2 ). Appropriate breast-feeding improves childhood immunity and reduces the incidence of gastroenteritis, malnutrition, otitis media, obesity and sudden infant death syndrome, as well as childhood mortality( Reference Goldman, Goldblum and Hanson 3 – 5 ). WHO/UNICEF has recommended the initiation of breast-feeding within the first hour of birth for all newborns, exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) until 6 months of age and continued breast-feeding until 2 years and beyond, including introduction of timely, adequate and safe complementary food at 6 months of age( 6 – 9 ). Despite these recommendations, a recent global estimate found that only 38 % of infants are exclusively breast-fed for the first 4 months of life( 7 ). Approximately 1·5 million lives of infants and young children are lost due to suboptimal feeding behaviours in developing countries including Nigeria( Reference Lauer, Betrán and Barros 10 ).

In 1992, following global recommendations, Nigeria introduced the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative to protect, support and promote breast-feeding among mothers( Reference Ogunlesi, Dedeke and Okeniyi 11 ), which resulted in improvements in EBF and early initiation of breast-feeding( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 – 14 ), and which has been shown to have significant impacts on neonatal diarrhoea, diarrhoeal dehydration and neonatal mortality elsewhere( 15 ). However, EBF prevalence in Nigeria has declined over time (from 28 % in 1999( 14 ) to 17 % in 2013( 13 )) and remains well below the recommended prevalence of 60 %( 16 ) needed to achieve Millennium Development Goal 4( Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 ). In contrast, the prevalence of bottle-feeding among Nigerian women has increased( 18 , Reference Chema and Chigbo 19 ), with evidence from regional studies suggesting an increase in bottle-feeding prevalence among infants from 16 % in 2008( 18 ) to 27 % in 2011( Reference Chema and Chigbo 19 ).

Few studies in Nigeria have investigated the determinants for these changes in optimal feeding practices. A recent study focused on determinants for early initiation of breast-feeding found that socio-economic factors (such as higher maternal education, employment and urban residency) and health service factors (such as higher frequency of antenatal visits and vaginal deliveries) positively impacted early initiation of breast-feeding, which also differed in magnitude over time( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 ). Nigeria is a society undergoing significant social and economic change( Reference Adewale 20 ). Globalization, a developing economy and changing political regime have engendered the growth of a new middle class in which familial and gender role differentiation (including social mobility of women) is in transition and may potentially be impacting infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices( Reference Omadjohwoefe 21 ).

To date, no studies have examined the key determinants of secular changes in other key breast-feeding indicators, including EBF, predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. Accordingly, the main purpose of the present study was to examine trends and differentials in key breast-feeding indicators (i.e. early initiation of breast-feeding, EBF, predominant breast-feeding, bottle-feeding) by socio-economic factors, health service factors and individual characteristics using the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) data over a period spanning 1999–2013. Findings from the study will provide an evidence base to policy makers and public health experts to evaluate the impact of previous interventions on feeding behaviours in Nigeria and to identify key drivers of changes to optimal feeding practices.

Methods

Data sources

The analysis was based on publicly available data sets collected for the NDHS for the years 1999, 2003, 2008 and 2013, conducted by the National Population Commission and ICF Macro( 13 , 14 , 18 , 22 ). The NDHS – a significant source of information on IYCF practices( 23 ) – collected information on IYCF practices (among other factors) from a nationally representative sample of households using the 1991 and 2006 census frames( 18 , 22 ). The NDHS data for 1999, 2003, 2008 and 2013 contained sociodemographic and eligible maternal responses from 8199, 7620, 33 385 and 38 948 mothers of reproductive age, respectively. The increase in sample size in the latter periods reflects growth in the Nigerian population and a broader survey scope to include additional modules of questions and geographic areas within geopolitical regions (to facilitate geo-coding). A total of 88 152 mothers were participants in the four data sets, with response rates ranging from 92 to 98 %. The samples were selected in a stratified two-stage cluster design. Using a face-to-face questionnaire, data on maternal and child’s demographics, breast-feeding and reproductive practices, as well as contraceptive and infant feeding practices, were collected.

Key breast-feeding indicators

The infant feeding indicators were assessed using the WHO recommended definition of breast-feeding indicators for assessing IYCF practices( 7 , 9 , 23 ). In the analysis, the main outcome factors were early initiation of breast-feeding within the first hour of birth, EBF, predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding using the following definitions.

-

1. Early initiation of breast-feeding: the proportion of children 0–23 months of age who were put to the breast within an hour of birth – this indicator was based on mother’s recall.

-

2. Exclusive breast-feeding: the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the only source of nourishment (but allow oral rehydration solution, drops or syrups of vitamins and medicines) – this indicator was based on mother’s recall on feeds given to the infant in the last 24 h.

-

3. Predominant breast-feeding: the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the predominant source of nourishment (but which allows water and water-based drinks, fruit juice, ritual fluids, oral rehydration solution, syrups or drops of vitamins) during the previous day.

-

4. Bottle-feeding rate: the proportion of infants 0–23 months of age who received any liquid (including breast milk) or semi-solid food from a bottle with nipple/teat.

In addition, EBF and early initiation of breast-feeding were included in analyses because of their association with infant nutrition, decreased morbidity and mortality among children under 5 years of age( Reference Ladomenou, Moschandreas and Kafatos 2 , Reference Black, Allan and Bhutta 24 ). Predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding were included due to their impacts on the increased risk of diarrhoeal illness and increased risk for childhood mortality( 6 , 7 , 25 , Reference De Zoysa and Martines 26 ). Each of these breast-feeding indicators was expressed as a dichotomous outcome. For example, respondents who exclusively breast-fed were coded as ‘1’ and those who did not were coded as ‘0’( Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 ). The same approach was employed for the other breast-feeding indicators.

Study factors

Study factors included a range of socio-economic, health service and individual factors. Socio-economic characteristics included the mother’s highest educational level (categorized as no education, primary education or secondary and above education) and employment status (categorized as not working or working in the past 12 months preceding the survey), household wealth index (categorized as poor, middle or rich) and partner’s highest educational level (categorized as no education, primary education or secondary and above education). The household wealth index was calculated as a score of household assets such as ownership of transportation devices, ownership of durable goods and household facilities, which was derived from a principal components analysis conducted by the National Population Commission and ICF Macro based on a methodology developed from previous Demographic and Health Surveys( 13 , 14 , 18 ). Principal components analysis was used to determine the weights for the wealth index based on information collected about household assets and facilities. The household wealth index was divided into three groups and labelled poor, middle and rich. Each household was assigned to one of these groups. The wealth index was constructed using methods recommended by the World Bank Poverty Network and UNICEF as described by Filmer and Pritchett( Reference Filmer and Pritchett 28 ), and was used in similar previously published studies( Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 , Reference Filmer and Pritchett 28 ).

Health service factors included the number of antenatal clinic (ANC) visits (categorized as no antenatal visit, one to three antenatal visits or four and above antenatal visits, reflecting the WHO four-visit ANC model for focused antenatal care)( 29 ), the place of delivery (home or health facility) and mode of delivery (caesarean section or vaginal). Type of delivery assistance received was also included and was categorized as health professionals, traditional birth attendants or untrained personnel. A traditional birth attendant is usually a woman who assists the mother during childbirth and who initially acquired her skills by delivering babies herself, or by working with other traditional birth attendants( 30 ). Also, the place and mode of delivery were combined to see the effect of caesarean deliveries and home deliveries on early initiation of breast-feeding( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 ), acknowledging that most Nigerian women give birth at home( 13 ) and there is an increase in prevalence of caesarean section in Nigerian health facilities( Reference Geidam, Audu and Kawuwa 31 , Reference Yakasai and Abubakar 32 ). Individual characteristics included age of the child in months.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the prevalence of breast-feeding indicators (early initiation of breast-feeding, EBF, predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding) were examined over the study period (1999–2013), stratified by socio-economic, health service and individual-level variables to determine absolute changes in prevalence. Prevalences and calculation of standard errors were adjusted using sampling weights to account for the cluster sampling design.

Relative differences between study factors were investigated using a series of univariable and multivariable multilevel logistic regression models. Study variables included socio-economic factors (employment status, maternal and partner’s education, household wealth index)( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 , Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 33 , Reference Lawoyin, Olawuyi and Onadeko 34 ), health service factors (place of delivery, mode and place of delivery, antenatal visits, delivery assistance)( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 , Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 33 , Reference Ekure, Antia-Obong and Udo 35 ) and individual factors (child age)( Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 ). Trends over the period were assessed by specifying period as an ordinal variable in models, stratified by each level of a given study variable to assess the extent to which prevalence within groups was increasing or decreasing. The extent of divergence or convergence between the slopes of period-specific trends within each study variable over the study period was assessed by testing the interaction (P for interaction) between period and a given study variable over the study period (1999–2013).

Multivariable models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of geopolitical region, maternal age, birth interval and sex of the baby. In models of health service factors additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status (SES), as a common cause (confounder) of the association between health service factors and optimal breast-feeding indicators. Similarly, in models of individual factors, additional adjustment was made for SES and health service factors as confounders of the association between individual factors and breast-feeding indicators.

The models restricted analyses to the youngest living child aged less than 24 months living with the respondent (eligible women aged 15–49 years). All analyses were carried out using the statistical software package Stata version 13·0, with prevalences calculated using the ‘Svy’ function to allow for cluster sampling and regression modelling conducted using the ‘xtlogit’ function.

Ethics

The Demographic and Health Surveys project sought and obtained the required ethical approvals from ethics committees in Nigeria before the surveys were conducted. Informed consent was obtained from study participants before they were allowed to participate in the surveys. The survey data sets used in the present study were completely anonymous with regard to participant identity. Approval was sought from MEASURE DHS/ICF International and permission was granted for this use.

Results

Early initiation of breast-feeding

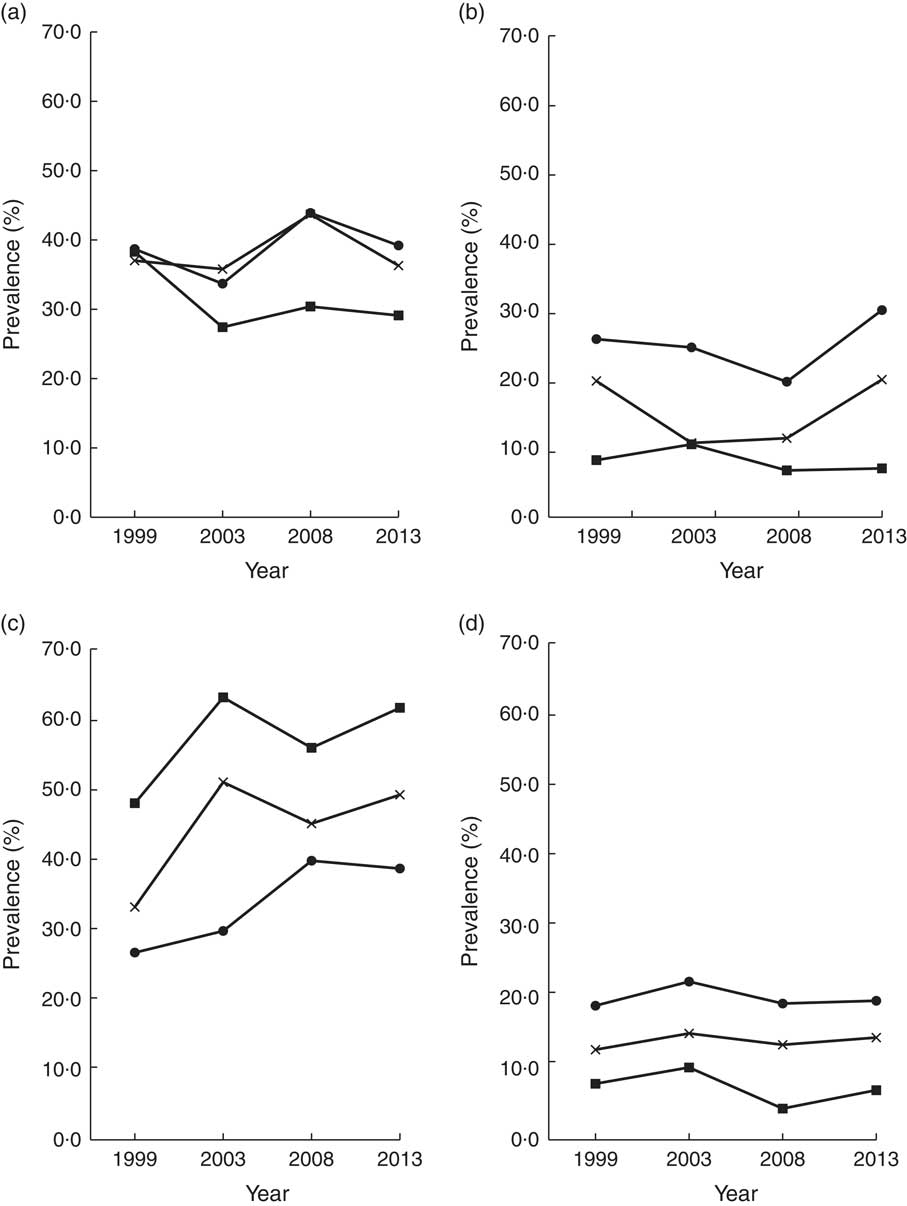

The proportion of mothers who engaged in early initiation of breast-feeding decreased significantly over the study period for mothers with no schooling but with a slight increase in the intervening year (2008) compared with educated mothers (Fig. 1(a)). Likewise, a similar decreasing trend was identified in mothers who received delivery assistance from non-health professionals (particularly untrained personnel) compared with mothers who received delivery assistance from health professionals (Table 1). Further, a similar decreasing trend was evident among mothers who delivered their babies by caesarean section, compared with mothers who delivered at home (Table 1). Mothers who delivered by caesarean section at a health facility were significantly less likely to initiate breast-feeding within the first hour of birth (2008–2013) compared with mothers who delivered at home. However, when place of delivery was stratified by home and health facility, the study found that mothers who delivered at a health facility were significantly more likely to initiate breast-feeding within the first hour of birth compared with mothers who delivered at home (Table 1). Mothers from wealthier households were significantly more likely to initiate breast-feeding within the first hour of birth compared with mothers from poorer households.

Fig. 1 Trends in key breast-feeding indicators by mother’s education level (![]() , no education;

, no education; ![]() , primary education;

, primary education; ![]() , secondary and above education): (a) early initiation of breast-feeding; (b) exclusive breast-feeding; (c) predominant breast-feeding; (d) bottle-feeding. Nigeria, 1999–2013

, secondary and above education): (a) early initiation of breast-feeding; (b) exclusive breast-feeding; (c) predominant breast-feeding; (d) bottle-feeding. Nigeria, 1999–2013

Table 1 Early initiation of breast-feeding by socio-economic, health service and Individual characteristics, Nigeria, 1999–2013

Ref., reference category.

%=proportion of mothers who engaged in early initiation of breast-feeding in the study population (0–23 months); P for interaction=interaction between a given study variable and the study period (1999–2013). Multivariable models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of geopolitical region, maternal age, birth interval and sex of the baby. In models of health service factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and individual factors. For models of individual factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and health service factors as confounders of the association between individual factors and breast-feeding indicators.

Exclusive breast-feeding

The study showed an increasing prevalence of EBF among educated mothers with some variability in the intervening years compared to mothers with no schooling (Fig. 1(b)). A significant increasing trend was evident in mothers who made more than four ANC visits compared with mothers who had no ANC visits (Table 2). Educated mothers were significantly more likely to exclusively breast-feed their babies over the study period compared with mothers without schooling (Table 2). The odds for EBF were higher for mothers from wealthier households compared with mothers from poorer households. Mothers who delivered at the health facility were significantly more likely to exclusively breast-feed compared with mothers who delivered their babies at home. Similarly, mothers who had more than four ANC visits were significantly more likely to practise EBF compared with mothers who had no ANC visits. Increasing child age was significantly associated with a less likelihood of EBF.

Table 2 Exclusive breast-feeding by socio-economic, health service and individual characteristics, Nigeria, 1999–2013

Ref., reference category.

%=proportion of mothers who exclusively breast-feed in the study population (0–5 months); P for interaction=interaction between a given study variable and the study period (1999–2013). Multivariable models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of geopolitical region, maternal age, birth interval and sex of the baby. In models of health service factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and individual factors. For models of individual factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and health service factors as confounders of the association between individual factors and breast-feeding indicators.

Predominant breast-feeding

The prevalence of predominant breast-feeding increased significantly among all mothers, irrespective of educational status, over the study period but was slightly lower in year 2008 for mothers with no schooling and mothers with primary level of education (Fig. 1(c)). Similar significant increasing trends were evident in mothers from all households and women who either had health service contact or not – particularly ANC visits and place of delivery (Table 3). Educated women and mothers from wealthier households were less likely to predominantly breast-feed their babies compared with women with no schooling and mothers from poorer households, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, mothers who made more than four ANC visits were less likely to predominantly breast-feed their babies compared with mothers who made no visits. Mothers who received delivery assistance from a non-health professional were significantly more likely to predominantly breast-feed their babies compared with mothers who delivered with the assistance of a health professional.

Table 3 Predominant breast-feeding by socio-economic, health service and individual characteristics, Nigeria 1999–2013

Ref., reference category.

%=proportion of mothers who predominantly breast-feed in the study population (0–5 months); P for interaction=interaction between a given study variable and the study period (1999–2013). Multivariable models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of geopolitical region, maternal age, birth interval and sex of the baby. In models of health service factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and individual factor. For models of individual factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and health service factors as confounders of the association between individual factors and breast-feeding indicators.

Bottle-feeding

The results showed a minimal increasing prevalence of educated mothers who bottle-fed their babies over the four time points, with some variability in the intervening years, compared with mothers with no schooling (Fig. 1(d)). A similar increasing trend was observed in mothers from wealthier households compared with mothers from poorer households (Table 4). Mothers who made more than four ANC visits were significantly more likely to bottle-feed their babies compared with mothers who had no antenatal visit (Table 4). Similarly, the odds for bottle-feeding were significantly higher for women who delivered vaginally at the health facility compared with women who delivered at home. Educated mothers and mothers from wealthier households were significantly more likely to bottle-feed their babies compared with mothers without schooling and mothers from poor households.

Table 4 Bottle-feeding by socio-economic, health service and Individual characteristics, Nigeria 1999–2013

Ref., reference category.

%=proportion of mothers who bottle-fed in the study population (0–23 months); P for interaction=interaction between a given study variable and the study period (1999–2013). Multivariable models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of geopolitical region, maternal age, birth interval and sex of the baby. In models of health service factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and individual factors. For models of individual factors, additional adjustment was made for socio-economic status and health service factors as confounders of the association between individual factors and breast-feeding indicators.

Discussion

The prevalence of EBF increased among educated mothers, women who had greater contact with health services and mothers from wealthier households over the study period (but with some variability in intervening years). However, there was an increasing prevalence for predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding among educated mothers compared with mothers with no schooling. The proportion of early initiation of breast-feeding decreased over the four time points but with a slight increase in the intervening year among women with no schooling and unemployed mothers, and among women from poorer households including mothers who had no health service contacts. Mothers from high SES groups and women who reported frequent health service contacts had better feeding behaviours compared with mothers from low SES groups and women who had no health service contacts. Increasing child age was associated with non-EBF, predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding.

A number of methodological considerations need to be taken into account in the interpretation of these findings. First, breast-feeding outcomes were based on self-report and this is a potential source of measurement bias whereby mothers may inaccurately recall how and when the child was fed during the periods referred to by the survey questions. Likewise, misclassification in key study variables may also have occurred, for example under- or overestimation of the number of health service visits. Selection bias is less likely to affect the observed results due to the nationally representative sampling and high response rate of the surveys. Selected samples were drawn from the 1999 and 2006 national census frame, yielding response rates between 92 and 98 % without significant differences between urban and rural areas.

The analysis showed that mothers from wealthier households and women with higher educational achievement exclusively breast-feed their babies compared with mothers from poorer households and women with no schooling, respectively, perhaps reflecting that mothers from higher SES groups are more likely to access and respond to health messages at a health facility( Reference Babalola and Fatusi 36 ) compared with mothers from lower SES groups. A previous study found that primary education is the minimum level required to gain from health promotion messages and it empowers vulnerable populations – especially women – to act on health messages( 37 ). Previous studies from Nigeria and Ghana are consistent with this finding, where women from poorer households with no educational achievement engaged in suboptimal feeding practices compared with women from wealthier households with higher educational achievement( Reference Ekure, Antia-Obong and Udo 35 , Reference Sika-Bright 38 ).

Employment was not associated with EBF in the present study; however, studies from regional Nigeria found that more than half (60–85 %) of female practising medical doctors engaged in suboptimal feeding practices due to pressure to resume work( Reference Agbo, Envuladu and Adams 39 , Reference Sadoh, Sadoh and Oniyelu 40 ). Aspects of specific work roles for women may be an explanation for the observed trend in feeding behaviours among higher SES mothers in Nigeria. Changes in female labour-force participation associated with socio-economic development in Nigeria may also be an additional factor associated with IYCF practices. Studies in Nigeria have also suggested a range of reasons why women do not exclusively breast-feed, including that EBF was very stressful( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 41 ), a perceived notion that the child continued to be hungry after breast-feeding( Reference Agunbiade and Ogunleye 42 , Reference Alutu and Orubu 43 ), a lack of family support( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 41 , Reference Agunbiade and Ogunleye 42 ), the existence of workplace barriers( Reference Agbo, Envuladu and Adams 39 , Reference Wole 44 ) and the increasingly prominent marketing practices of infant food manufacturers( Reference Okafor 45 ). A response to the low prevalence of EBF in Nigeria has been a recent regional government initiative that introduced 10 d paid paternity leave for male public servants and extended paid maternity leave for female public officers from 3 to 6 months, with the promotion of EBF being part of the rationale for this initiative( Reference Olufowobi 46 ). Previous studies in Nigeria and Tanzania found that mothers of higher educational achievement were more likely to engage in EBF compared with mothers with no schooling( Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 27 , Reference Ekure, Antia-Obong and Udo 35 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 47 ).

In comparing Nigeria with other African countries (such as South Africa) with a significant resource-based economy and a growing middle class( Reference Magnowski 48 ) including low breast-feeding indices( 49 ), a randomized controlled trial in South Africa found that antenatal intention not to breast-feed and mothers with a personal income had increased risk of poor feeding practices compared with mothers without personal income( Reference Doherty, Sanders and Swanevelder 50 ). Studies from South Africa also suggested that the fear of maternal-to-child transmission of HIV has been responsible for the poor feeding behaviours reported in South Africa( Reference Doherty, Sanders and Swanevelder 50 ); however, most South African studies found that the risk of HIV transmission was lower among exclusively breast-fed infants compared with infants who received mixed feeding( Reference Coutsoudis, Pillay and Spooner 51 , Reference Iliff, Piwoz and Tavengwa 52 ).

Information received during health service contacts – more likely to be accessed by higher SES women( Reference Babalola and Fatusi 36 , Reference Abosse, Woldie and Ololo 53 – Reference Simkhada, Teijlingen and Porter 55 ) – may also be an important driver of trends in optimal feeding practices. A previous Nigerian study found that mothers who had more contact with health services received information on optimal feeding practices( Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 33 ). Similarly, the analysis found that mothers who had greater access to health services exclusively breast-fed their babies compared with mothers who had no health service access, suggesting that mothers may have received appropriate information on feeding practices during antenatal, partum and postnatal periods. Studies from Nigeria found that nursing mothers have good knowledge and positive attitude towards breast-feeding( Reference Chema and Chigbo 19 , Reference Mbada, Olowookere and Faronbi 56 , Reference Peterside, Kunle-Olowu and Duru 57 ) and that women with greater access to a health facility were more likely to receive and respond to health promotion messages( Reference Doctor, Bairagi and Findley 58 ). A review of a regional Nigerian government initiative (free maternal and child health services) found an increase in health service access among women and better maternal and child health outcomes( Reference Galadanci, Idris and Sadauki 59 , Reference Okafor, Obi and Ugwu 60 ). Accordingly, to improve feeding practices in Nigerian women, sub-national (states and local councils) intervention programmes that would ensure better health service access to mothers from lower SES groups is proposed as an adjunct to the full implementation and sustainability of the Millennium Development Goals project.

Early initiation of breast-feeding is important for providing newborns with immunity to resist respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases( Reference Edmond, Zandoh and Quigley 61 , Reference Clemens, Elyazeed and Rao 62 ). In the current study, mothers who had more than four ANC visits and those who delivered at the health facility more often initiated breast-feeding within the first hour of birth compared with mothers who had no ANC visit and those who delivered at home. This suggests that mothers who had greater health service contacts may have received adequate health information about optimal feeding behaviours, acknowledging that health service contacts – especially ANC visits – offer an important opportunity for communicating health promotion messages. Studies in developed countries like Australia( 63 ) and the USA( 64 ) found the prevalence of early initiation of breast-feeding to be at least 90 %, signifying that the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative can operate very well in the context of early initiation of breast-feeding. However, similar studies in Nigeria found the prevalence of early initiation of breast-feeding to be very low (33–38 %)( 13 , 18 ) and that mothers who delivered vaginally at home or by caesarean section at a health facility were more likely to delay initiation of breast-feeding compared with mothers who delivered vaginally at a health facility( Reference Yahya and Adebayo 12 ). Similarly, studies from Ghana and an international review found that delivering by caesarean section remains a significant impediment to early initiation of breast-feeding especially in developing countries. Most deliveries occur at home in Nigeria( 13 , Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 17 ), and this may be a reason for the low prevalence of early initiation of breast-feeding. A response to this observed deficit was the Baby-Friendly Community Initiative proposed by WHO/UNICEF to promote, protect and support optimal feeding practices at the community level, which has been shown to be successful elsewhere( 5 ).

The present analysis found that educated mothers and mothers from wealthier households were significantly more likely to bottle-feed their babies compared with mothers with no schooling and mothers from poor households, suggesting that mothers of higher SES are more likely to have the material resources to purchase formula feeds. In Nigeria, poor national policies, prominent marketing practices of breast-milk substitutes and ignorance of the risks of bottle-feeding by nursing mothers have been identified as determinants for the increasing trend of bottle-feeding( Reference Okafor 45 ), as well as work environments that do not support breast-feeding mothers( Reference Agbo, Envuladu and Adams 39 ). An international literature review found that working mothers in developing countries like Nigeria usually turn to breast-milk substitutes for feeding of their newborn( Reference Glick 65 ) and this may be another factor driving the increase trend in bottle-feeding among women of higher SES in Nigeria. Studies in Ghana have similar findings, where mothers of higher SES were more likely to use breast-milk substitute compared with mothers of lower SES( Reference Sika-Bright 38 , Reference Sika-Bright 66 ).

Nigerian data from the Millennium Development Goals performance tracking survey showed social complexities that indicate breast-feeding promotion needs to be context specific( 67 ). Nigeria is the most populous country and largest economy in Africa, sharing a growing middle class and significant resource-based economy with other African countries (such as South Africa and Ghana)( Reference Magnowski 48 , Reference Ohuocha 68 , 69 ), and the feeding practices observed in Nigeria could be extrapolated to similar African countries. Findings from the present study suggest that high SES women engaged in EBF and early initiation of breast-feeding compared with low SES women; however, mothers in high SES groups also significantly engaged in predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding, suggesting that the duration of EBF practised by many high SES women was suboptimal. This finding has previously been reported in Nigerian and Brazilian studies where high SES women engaged in suboptimal EBF, due largely to pressure to resume work postnatally, compared with low SES women( Reference Ekure, Antia-Obong and Udo 35 , Reference Mascarenhas, Albernaz and da Silva 70 ). Further, lower SES mothers and women who reported no health service contacts had poorer feeding practices. Studies have shown that poorly breast-fed children have an increased risk of developing obesity( Reference Shields, O’Callaghan and Williams 71 ), asthma( Reference Oddy, Holt and Sly 72 ), allergic conditions( Reference Oddy, Holt and Sly 72 ) and type 1 diabetes( Reference Sadauskaite-Kuehne, Ludvigsson and Padaiga 73 ); and women reporting not to breast-feed are more likely to develop ovarian cancer( Reference Whittmore, Harris and Itnyre 74 , Reference Luan, Wu and Gong 75 ), rheumatoid arthritis( Reference Brun, Nilssen and Kvåle 76 , Reference Pikwer, Bergström and Nilsson 77 ) and type 2 diabetes( Reference Taylor, Kacmar and Nothnagle 78 ). National, state and local council intervention policies and programmes are needed to improve the current feeding practices in Nigeria and should target all mothers regardless of SES.

Conclusion

The present study found a significant increasing trend in EBF and early initiation of breast-feeding among mothers of higher SES and mothers who had a higher frequency of health service access. However, nursing mothers of higher SES groups and mothers who reported more frequent health service use also engaged in predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding practices. Mothers from lower SES groups and women who made no health service contacts delayed initiation of breast-feeding and engaged in non-EBF compared with mothers from high SES groups and women who made health service contacts.

National policies that underpin IYCF practices in the workplace and consider the extent and appropriateness of advertising by infant food manufacturers are perhaps responses to address these factors affecting optimal feeding practices in Nigeria. Additionally, sub-national (state and local government council) programmes and facility-based programmes that promote the baby-friendly hospital initiatives for families and health-care professionals, including broader community-based interventions (such as baby-friendly community initiatives) for non-health professionals who support nursing mothers in the communities, are also recommended as adjuncts to improve IYCF practices among Nigerian mothers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to MEASURE DHS/ORC Macro, Calverton, MD, USA for providing the 1999–2013 NDHS data for this analysis. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: F.A.O. contributed to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. A.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revisions of the manuscript. K.E.A. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revisions of the manuscript. F.C. contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Required ethical approvals were obtained from ethics committees in Nigeria before the NDHS rounds were conducted. MEASURE DHS/ICF International granted permission to use these data in the present analysis.