How did colonialism impact African monetary systems? There is now a substantial literature debating the impact of colonial policies which were intended to impose single currencies linked to metropolitan monetary systems within colonial boundaries.Footnote 1 Such policies served a number of purposes for colonial governments, ranging from a reduction in transaction costs for merchants and governments to a physical and symbolic demonstration of colonial control (Helleiner Reference Helleiner2002). However, the slow and uneven displacement of precolonial currencies by colonial coins and notes also revealed the limits of that control. Africans not only continued to use indigenous currencies such as cowrie shells and kissi pennies, but also retained long-standing practices of negotiating values between multiple currencies (Guyer Reference Guyer2004).

This literature has focused primarily on the opening decades of the colonial period and on the relationship between colonial and indigenous currencies. It has, however, generally neglected the fact that the colonial period as a whole was one of significant monetary instability affecting metropolitan states and, by extension, the African economies linked to them through colonialism. During the period of colonial conquest in Africa, European currencies (and the colonial currencies linked to them) enjoyed stable rates of exchange through the collective enforcement of the pre-war gold standard. This stability vanished with the outbreak of World War I, when imperial powers first abandoned the gold standard and then attempted unsuccessfully to revive it. This instability makes this period, as Barry Eichengreen puts it, one with “an exceptionally rich menu of international monetary experience” (Reference Eichengreen1990:1–2). While this menu has been widely explored for Europe and North America, the impact of this interwar monetary instability on colonial economies remains neglected. How did fluctuations in the exchange rates of colonial currencies impact the monetary systems which had emerged in Africa during the early colonial period? To what extent were colonial states able to manage this instability? And how did producers, merchants, and other stakeholders respond to the rapidly changing global economic situation?

This article explores these questions through a discussion of three different crises for African states during the 1920s and 1930s which were directly tied to fluctuations in the exchange rates of colonial currencies. These include the demonetization of the franc in The Gambia, the rupee crisis in Kenya, and independent Liberia’s shift from using British West African currencies to the US dollar. Together, these incidents illustrate three points about the impact of colonialism and globalization on African monetary systems. First, they go beyond existing arguments about the limits of colonial power to show the degree to which African governments struggled to adapt to changing global economic conditions. All three crises originated in some way in policies adopted during the era of gold standard stability which later became untenable. Second, they show that Africans’ facility with managing multiple currencies extended to the colonial currencies in circulation, and Africans responded readily to opportunities for arbitrage profits created by exchange rate fluctuations—marginal gains for the colonial era. Finally, they suggest that any comprehensive history of interwar monetary instability and the collapse of the gold standard needs to look beyond Europe to consider the impact on economies linked to European monetary systems through colonialism.

A Colonial Currency Revolution?

There are two conflicting narratives about the impact of colonialism on Africa’s monetary systems. According to one, the expansion of coastal trade from the early modern period led to an influx of cowries, textiles, and other items used as currency. This, in turn, led to inflation and the eventual abandonment of such currencies by the early twentieth century in favor of the coins and notes issued by colonial governments. A.G. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins1966) described this shift as a “currency revolution.” The “revolution” label, and the comprehensive change it implies, has been contested by other authors who argue that African currency systems were able to adapt to changing trade patterns, and that the impact of colonial policies was neither as rapid nor as far-reaching as colonial governments would have liked (Ofonagoro Reference Ofonagoro1979; Guyer Reference Guyer and Guyer1995; Saul Reference Saul2004).

Africa’s monetary systems during the early modern period were characterized not by territorial uniformity but rather by the simultaneous use of multiple currencies across the same geographical and political space. This was not unique to Africa. Across much of the world, national currencies circulating within fixed territories were an innovation of the nineteenth century, when an increase in state capacity allowed governments to use currencies both as a source of revenue and as a symbol of political cohesion (Cohen Reference Cohen1998). Prior to that, however, people mediated between different types of currencies. The uses of currency, and the values assigned to different commodities, were situational in nature. Jane Guyer (Reference Guyer2004) argues that Africans used this situational variation as a means of coping with economic instability, building institutions which helped create incomes out of uncertain economic circumstances. The addition of European currencies to the mix did not change these overall patterns, and European merchants also sought profits from the interchange between different types of currencies. Hopkins, for example, writes with regard to Lagos that “European firms clung to cowries and barter as long as possible because they considered that exchange on this basis was more profitable, and less competitive, than a cash trade” (Reference Hopkins1966:483).

The system of multiple currencies did not serve the interests of colonial governments, however, though they did not immediately try to change it. The use of different currencies, and the variation in their relative values, introduced uncertainty into the transactions of European merchants and government officials, leaving colonial governments with several incentives to try and standardize the currencies in use within their territories. Eric Helleiner (Reference Helleiner2002) argues that the introduction of new colonial currencies served five potential purposes: 1) reducing intra-empire transaction costs; 2) reducing domestic transaction costs within the colony; 3) gaining influence over macroeconomic performance within the colonies; 4) providing seigniorage revenue; and 5) consolidating political identities.

In principle, the simplest way to achieve this was to impose metropolitan currencies across all of the colonies. This was attempted in the British empire in 1815, when the British government endeavored to introduce British coin into all of its colonies. This was intended, principally, to reduce the costs of transferring money to colonial troops (Chalmers Reference Chalmers1893:23–24). However, there were difficulties in reconciling a uniform currency policy with the diverse economic contexts of colonies which stretched from the Americas to Asia and Africa. By the late nineteenth century, British officials had reached a compromise whereby colonies fell into a small number of regional groupings, each with currencies backed by either sterling or gold (Clauson Reference Clauson1944).

This process has been studied in greatest detail for West Africa. During the nineteenth century, trade between Europe and West Africa increased rapidly, driven primarily by the growing demand for palm oil to be used as lubricant and soap in industrializing countries (Frankema, Williamson, & Woltjer Reference Frankema, Williamson and Woltjer2018). The currency most widely used in the palm oil trade was the British silver shilling coin. Despite its silver content, the shilling coin was a token coin, its value in Britain maintained through the careful management of supply and demand, and by the fact that the coins were only used for small-scale transactions. By the end of the nineteenth century, the volume of shilling coins circulating in West Africa was substantial, and the coins were widely used for both large and small transactions. As a result, British officials began to fear that in West Africa as well as other British territories, the value of the coin would begin to depreciate, resulting in a loss of exchange rate stability within the empire. They also worried that, in the event of a serious West African trade depression, a sufficient number of the coins would be repatriated to Britain that their value would be threatened (Hopkins Reference Hopkins1970:105).

To these concerns were added those of colonial officials after the establishment of formal colonial administration in the region. Initially, they operated within the indigenous currency systems of the region, collecting taxes and paying workers in already circulating currencies such as textiles and cowries. However, the fluctuating values of these currencies (relative to each other and to British sterling) made it difficult to draw up the balanced budgets demanded by the Treasury (Gardner Reference Gardner2012).

To resolve both of these issues, the British government opted in 1912 to establish a separate currency, the West African pound, for the four British West African colonies. The West African pound was issued by the West African Currency Board (WACB), which was headquartered in London and could only issue the new currency in exchange for an equal amount of sterling deposits. These restrictions on WACB policies meant that, of Helleiner’s five purposes, macroeconomic management took a backseat to the reduction of transaction costs, production of revenue, and demonstration of political authority. The strict 100 percent reserve ratio ensured that the West African pound remained at parity with its metropolitan equivalent, though it also tied up funds which might have been used for local development purposes. As J.S. Hogendorn and H.A. Gemery note, the WACB’s sterling reserve “was invested mainly in UK national and local government bonds and securities; in practice the WACB did not buy the bonds or securities of its constituent territories” (Reference Hogendorn and Gemery1988:141). West African colonial governments did share the revenue generated by the minting of the currency, though this never amounted to a large share of total revenue because of the WACB’s policy of maintaining high reserves and because seigniorage revenue was used to pay the operating costs of the Board.

How big an impact the creation of these new currencies had on African economies remains a matter for debate. Were colonial governments able to impose their will with regard to currency use unilaterally on their subjects? Did Africans begin to use colonial currencies voluntarily in order to have a more stable currency with which to purchase imports? Or did they resist their use as a means of resisting the imposition of colonial authority? To what extent did policies regarding taxation and wage labor counter such resistance? In his account of what he called the West African “currency revolution,” Hopkins (Reference Hopkins1966) argued that the depreciation of cowries and other indigenous currency objects through increased trade generated a demand for British currency. The rapid increase in imports of shilling coins supports this argument. However, others point to the continued use of indigenous currencies well past the introduction of colonial currencies to suggest that the ability of colonial governments to get their way was severely limited. Africans, it seemed, preferred to continue to use other currencies for particular types of transactions, because they were better suited in terms of denomination, or cultural preference, or as a rejection of colonial authority (Naanen Reference Naanen1993; Ofonagoro Reference Ofonagoro1979; Saul Reference Saul2004; Mwangi Reference Mwangi2001).

Subsequent sections will demonstrate that the limits of colonial authority were not only in evidence with regard to the use of indigenous currencies. Colonial governments also allowed exceptions to policies of territorial uniformity with regard to the range of non-African currencies circulating at the time. French francs circulated in British Africa, while British currency was used outside the bounds of British territory. In East Africa, the rupee continued to circulate even after the colonial government adopted policies to attract British settlers. Under the conditions of the pre-war gold standard, colonial policies were made on the assumption that gold exchange standard currencies were, in effect, interchangeable in a colonial context and that their circulation would not impact the primary goal of colonial currency systems, namely the reduction of transaction costs and exchange rate risks. These assumptions were proven incorrect with the collapse of the gold standard during World War I, and during the interwar period, colonial governments struggled to manage the challenges created by fluctuating exchange rates.

Colonialism, Globalization, and Interwar Instability

Before examining the three crises, some additional background on global monetary history—in particular the rise and fall of the gold standard—is needed, as this broader history shaped some of the uncertainties facing colonial governments during the 1920s and 1930s. The colonial conquest of Africa took place alongside a process of financial globalization which saw unprecedented flows of capital from Europe, and particularly Britain, to the rest of the world. This process of financial globalization, which extended across the period from around 1880 until 1914, was underpinned by a long period of stable rates of exchange between currencies backed by gold under the pre-war gold exchange standard (Flandreau & Zumer Reference Flandreau and Zumer2003). If exchange rates were stable, people could trade and invest without worrying about the risk of exchange rates changing later. According to the classic interpretation by Michael Bordo and Hugh Rockoff, “common adherence to gold convertibility… linked the world together through fixed exchange rates” (Reference Bordo and Rockoff1996:389).

Colonial monetary policies, with all their limitations, extended this principle to colonies as well as to metropolitan states, though the impact of joining the gold standard has been less widely explored for colonies. Still, it enabled colonial economies to participate in the process of financial globalization in ways which had lasting impacts on their patterns of development over this period. Maurice Obstfeld and Alan Taylor (Reference Obstfeld and Taylor2003), for example, argue that it was membership in the gold standard which explains why colonies were able to borrow at lower costs than their economic fundamentals might otherwise have allowed. Though this explanation is disputed, and borrowing by African colonies in particular depended on the intervention of a range of colonial institutions, the fact that colonial governments could raise funds on better terms than independent governments is not in question.Footnote 2 Foreign capital raised by colonial governments went largely toward investments in infrastructure, particularly railways, which recent work has shown increased incomes for some producers while also creating lasting spatial inequalities (Jedwab & Moradi Reference Jedwab and Moradi2016; Jedwab, Kerby, & Moradi Reference Jedwab, Kerby and Moradi2017).

The outbreak of World War I saw the end of the pre-war gold standard, as the immediate financial demands of the war effort led leading combatant countries to abandon their gold pegs in order to retain their gold reserves and free up their central banks to use a wider range of tools (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2008:60–61). After the war was over, there were attempts to reconstruct the pre-war system. With the support of the US government, Britain re-pegged the pound to the dollar but suspended convertibility when it became obvious that it would not be able to sustain that value without American help. Other countries followed suit, and central banks did not intervene, making the 1920s a rare historical episode of floating exchange rates. Financial historians have spilled much ink discussing how this sequence of events occurred, focusing particularly on what motivated metropolitan decisions to float or try to stabilize their currencies after the war (see, e.g., Broadberry Reference Broadberry1986:ch 12; Dimsdale Reference Dimsdale, Eltis and Sinclair1981; Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2008:51–57; Feinstein, Temin, & Toniolo Reference Feinstein, Temin and Toniolo2008:ch 3; Moggridge Reference Moggridge1972). However, this historiography does not reflect the fact that the colonial expansions of the nineteenth century had extended the currencies of these countries into many parts of the world.

Historians of Africa have long identified the interwar period as a significant one in which, with the benefit of hindsight, it is possible to see some of the cracks preceding the ultimate collapse of colonial rule. Prior to the interwar period, the aim of colonial development policies had been to maximize the production and export of a small range of primary commodities. In a globalizing world, such specialization seemed the most efficient means of generating sufficient revenue to make colonial governments more sustainable. However, this dependence on a small number of commodity exports made colonial economies extremely vulnerable to the series of economic shocks which began with the outbreak of World War I (Hopkins Reference Hopkins1973; Havinden & Meredith Reference Havinden and Meredith1993). During the war shipping was stalled, and prices for African commodities became extremely volatile. This volatility continued after the war, affecting the incomes of producers, merchant firms, and colonial governments. The latter responded by increasing pressure on African taxpayers, raising rates of tax and increasing rates of imprisonment for tax defaulters (Gardner Reference Gardner2012).

The impacts of these shocks on African producers and laborers prompted a rapid expansion of organized political resistance to colonial policies. Newly established political associations drew on ideas about government intervention and taxpayer welfare which were emerging elsewhere in the world to demand, if not yet full independence, at least a new political settlement with colonial states (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale1968). The responses of colonial governments to these demands ranged from violent repression to a grudging expansion of public services such as healthcare and education (Gardner Reference Gardner2012).

While this side of the story is well known, the impact of interwar instability on African monetary systems in particular has not been widely explored. This is despite the fact that, as one wider history of money and empire states, “money was integral to this overriding atmosphere of disturbance and disorder, as can be observed in the plural and complex monetary landscapes that spread everywhere, not only on the margins of the global system (on the so-called ‘peripheries’ of modernity) but also in the old and new metropolises and in new geopolitical units such as the nation state” (Neiburg & Dodd Reference Neiburg, Dodd, Neiburg and Dodd2021:3). Existing histories of the “currency revolution” have illustrated the rise of plural monetary systems unique to each colony. How did various stakeholders in these systems—from African producers to merchants to the colonial government—respond to the growing disorder of the monetary system?

The patchwork nature of colonial policies makes case studies the best way to illustrate both the struggles of colonial governments to manage interwar instability and the responses of Africans to the opportunities it generated. The next section considers the demonetization of the French franc in The Gambia, illustrating the degree to which colonial governments struggled to respond to a rapidly changing global economy. A second case examines the ways in which the demonetization of the rupee in East Africa divided different interest groups. Finally, the third case, on the displacement of British sterling by the US dollar in independent Liberia, shows that the same pressures affected independent governments as well as colonial administrations. Some of these three crises have been written about more extensively than others, but only ever in isolation as comparatively minor events in the economic and monetary histories of each individual country. Bringing them together in a comparative view illustrates that what look like local idiosyncrasies signal wider difficulties in the implementation of colonial currency policies and the ways in which colonialism brought Africa into the international monetary system. The conclusion draws out these more systematic issues, arguing that they offer a new perspective on colonial monetary systems.

Demonetizing the Franc in The Gambia

Colonial policy was rarely uniform even within empires, and the history of colonial rule shows that colonial officials readily made exceptions to accommodate various features of local economies they did not believe they could change. Currency policy was no different, and even after the establishment of the WACB the French franc circulated in parts of British West Africa, particularly in Sierra Leone and The Gambia. The five-franc coin in particular was closely tied to the groundnut trade, despite the fact that both colonies were under British rule. When the pound-franc exchange rate began to fluctuate during and after World War I, merchants were just as quick to exploit arbitrage opportunities, which exposed colonial governments to significant costs. While the colonial administration in Sierra Leone demonetized the franc fairly quickly, that of The Gambia delayed action until 1922 because of disputes about the impact demonetization would have on the production of groundnuts, The Gambia’s main export, and thus on the finances of the colonial government (Gardner Reference Gardner2015).

The circulation of French francs, and particularly the five-franc coin, was a legacy of the development of commodity trades during the nineteenth century, when particular European currencies were often linked to specific trades. During this period, the British shilling became associated with the palm oil trade, and French five-franc coins with groundnuts (Hogendorn & Gemery Reference Hogendorn and Gemery1988:140). By the middle of the century, this association was sufficiently well established that the 1843 order-in-council which established the British colonial government in The Gambia made five-franc coins legal tender throughout the territory at three shillings, ten and a half pence. Outside government transactions, the usual rate of exchange for the coins, referred to locally as dollars, was four shillings. In 1900 a government commission, the Barbour Committee, which was tasked with investigating currency matters in West Africa, concluded that “a large amount of the money spent in these colonies is earned in the interior in French territory… and it has been urged that the demonetization of the five-franc piece would deter natives from coming” into The Gambia.Footnote 3

This arrangement caused few issues while the rate of exchange between the pound and the franc remained relatively stable. No systematic data exist on the number of five-franc coins in circulation, but evidence from the early twentieth century suggests it was substantial. In 1900, the collector of customs in The Gambia testified to the Barbour Committee that traders “come from the southern Soudan, and from Bida in caravans that take three months, and bring in bags full of dollars that they have derived from the French, and spend it in the Gambia.” Import duties on the goods they purchased were the primary source of revenue for the colonial government, leaving officials wary of any attempt to demonetize the franc. In arguing the case against demonetization, the colonial government estimated in 1916 that “probably from 50 to 70 percent of payments in trade with natives of the Protectorate” were made using the five-franc coin.Footnote 4

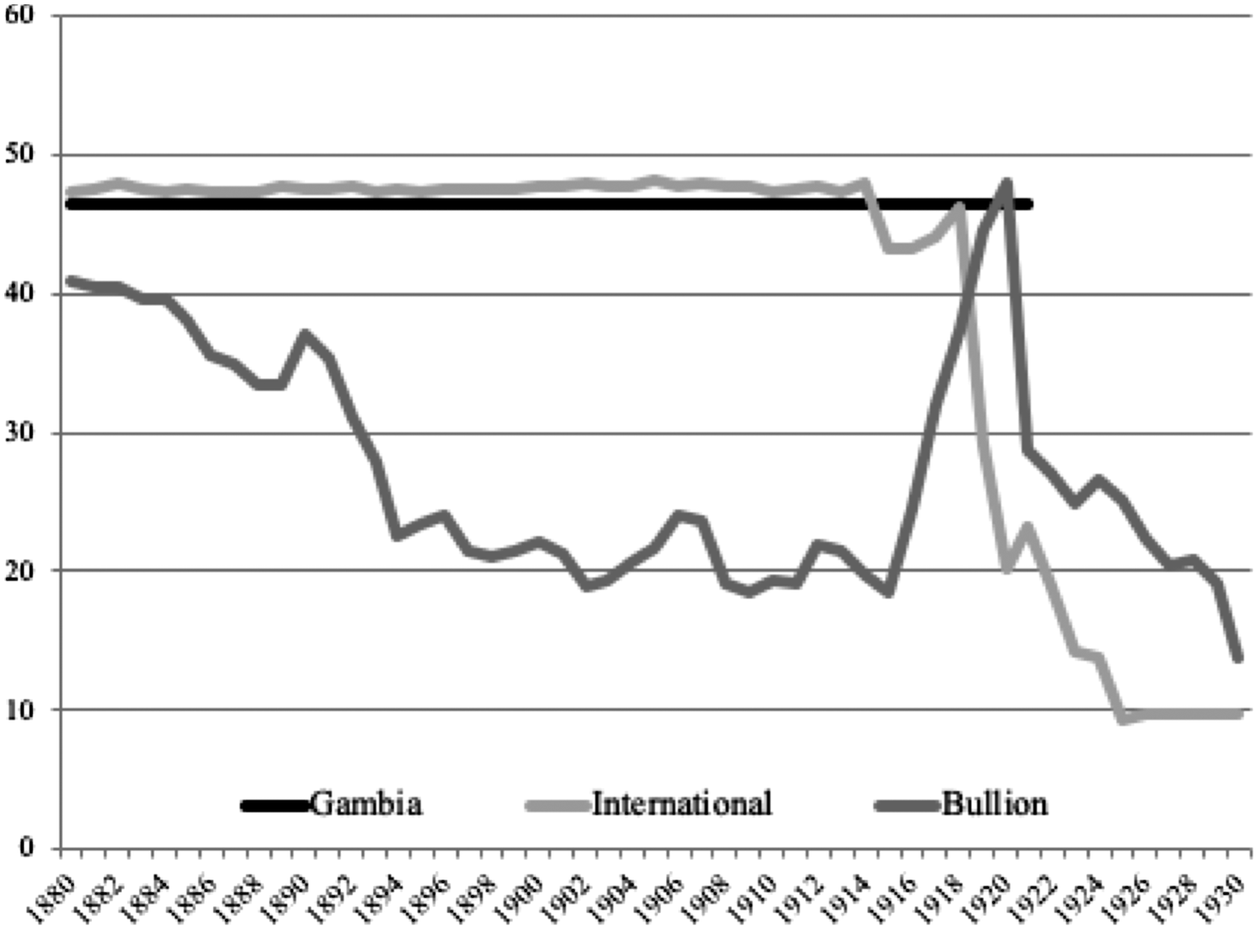

When Britain abandoned the gold standard during World War I, however, the exchange rate began to deviate from the pre-war level, with the franc depreciating against the pound. The value in British pence of five francs on the international market fell to 43 pence during the war (from a pre-war value of 48). It recovered briefly in 1918, but then fell again to 20 pence. Figure 1 gives the value of the five-franc coin according to three measures: the flat rate fixed by The Gambia’s order-in-council; the fluctuating international rate; and the market price of the silver bullion from which the coin was made.

The graph shows the opportunities for arbitrage which emerged with the fluctuating exchange rates. In 1915, Leslie Couper, director of the Bank of British West Africa, wrote to the Colonial Office warning them about the potential costs to the colonial governments of both The Gambia and Sierra Leone, which had the same fixed rate enshrined in local legislation. “The legal tender rate of the five-franc piece is 3/10 ½, although the actual sterling value of the coin, based on the present London-Paris exchange rate, is now 3/5 1/2d. This condition of affairs is obviously unsatisfactory and opens the door to losses to the governments of these colonies.”Footnote 5 In July 1916, a British official in the Colonial Office noted in regard to Sierra Leone that “owing to the recent course of exchange it actually pays to import the pieces; get a draft on London (directly or indirectly) from the Bank for these pieces at the 3/10 rate (the actual rate varying lately from 3/5 ½ to 3/6 ½); with the proceeds import French pieces; thus ad infinitum.”Footnote 6

This continued through the war, worsening as exchange rates fluctuated. In November 1921, a Colonial Office memorandum observed that “the withdrawal of alloy coin shows that someone is alive to the profit of taking alloy coins to Senegal, changing them for 5/- francs and smuggling the five-franc pieces back to Bathurst for exchange into alloy coins again.”Footnote 7 It was further reported that “merchants are purchasing money orders for remittances to Freetown on so considerable a scale as to involve this government in heavy loss… Money orders for GBP12,000, practically the whole of which have been paid in five franc pieces, have been issued during the last three and a half months as against a total of GBP7,418 for the whole of last year.” The scale of these transfers was sufficiently large that the colonial administration in The Gambia had to liquidate deposits in England to reimburse the Sierra Leone government.Footnote 8

Despite the accumulation of fiscal losses, and the ever-growing alarm of government officials, the coin was not demonetized until January 1922. The colonial government set up a special office of the Treasury in Bathurst, along with exchange depots at seventeen stations throughout the interior. The government yacht, the Mansa Kila Ba, traveled up and down the Gambia River collecting the coins. In the first part of the year, some GBP407,950 in British West African currency was paid out in return for more than two million five-franc coins.

The government then had to choose between exchanging the five-franc coins for British currency at the international rate of 1s 11d or shipping them to London to be melted down as bullion. As the bullion rate was then higher than the nominal value, they chose the latter strategy, but still they incurred significant losses. To cover the costs, the colonial administration had to borrow GBP187,893 from the West African Currency Board. The loan was repaid over the next decade, with a total expenditure of GBP230,000, in addition to the costs of the demonetization exercise, which came to GBP7,237. These costs can be compared with total annual public revenue in this period of just over GBP200,000. Repayments of the loan constituted around ten percent of the budget over the next decade, and as a result, planned infrastructure improvements were “abandoned temporarily.”Footnote 9

The case of the long and costly delay in the demonetization of the franc shows the extent to which colonial governments struggled to cope with the monetary instabilities of the interwar period. Fears of undermining local trade patterns made colonial officials in The Gambia, in particular, reluctant to abandon policies adopted before the war which exposed them to risk during and after it. In this case, the policy in question—the acceptance as legal tender of the five-franc coin—violated the principle of territorial uniformity assumed to be at the heart of colonial monetary policies. The case also shows that the long tradition of marginal gains in African monetary systems meant that merchants were quick to take advantage of opportunities for arbitrage profits when they emerged.

From the Rupee to the Shilling in East Africa

Just as colonial officials in The Gambia were struggling to cope with the depreciation of the franc, a similar crisis was brewing in East Africa over the appreciation of the rupee against the pound. This appreciation began during World War I but accelerated in 1919. East Africa was part of a group of British colonies which used the rupee as their official currency, known as the “rupee group.” These included, in addition to India itself, Aden, British Somaliland, Ceylon, the Seychelles, and Mauritius (Clauson Reference Clauson1944). All of these places had historical economic links to India via the Indian Ocean trade, and early colonial rulers in all of them depended heavily on the movement of people and goods from the subcontinent. As the colonial period progressed, however, some colonial administrations—notably in Kenya—began to promote British settlement, weakening the colony’s earlier ties with India.

The rupee became the official currency of British East Africa in 1898 (Maxon Reference Maxon1989:324; Pallaver Reference Pallaver2019:4). Indian labor had been essential in the construction of the Uganda railway, and by the early twentieth century East Africa was home to a substantial Indian commercial class on which the colonial government relied for the functioning of local markets. In 1905 the government set the value of the rupee as 15 to the gold sovereign, or 1s 4d (16 pence) to the rupee.Footnote 10 This rate, fixed in colonial legislation, was the stable rate of exchange under the pre-war gold exchange standard, which India had joined in 1898 (Balachandran Reference Balachandran1996:27; Chandavarkar Reference Chandavarkar, Kumar and Desai1983:771–72).

The adoption of the rupee as the colonial currency of East Africa, while reflecting historical links with the subcontinent, was not necessarily consistent with other colonial policies adopted at the same time. In Kenya, in particular, an early emphasis on Indian ties was abandoned in 1903 under the governorship of Sir Charles Eliot. In its early decades, the colonial administration of what was then British East Africa, later renamed Kenya, struggled to build a revenue base and remained dependent on transfers from a reluctant British treasury. Eliot believed the solution to this was not strengthening ties to India but rather encouraging British settlement. Land was offered on favorable terms, and in Kenya there was a particular effort to attract settlers with access to large amounts of British capital through personal incomes or assets held in the metropole. As a result of these policies, Dane Kennedy notes that Kenya was known as the “officer’s mess” of the British empire, while Southern Rhodesia was described as the “sergeant’s mess” (Reference Kennedy1987:6). By the outbreak of World War I, a small but influential community of settlers had emerged, laying the foundation for what would remain constant tensions over the interests of the African, Asian, and European populations over the rest of the colonial period.

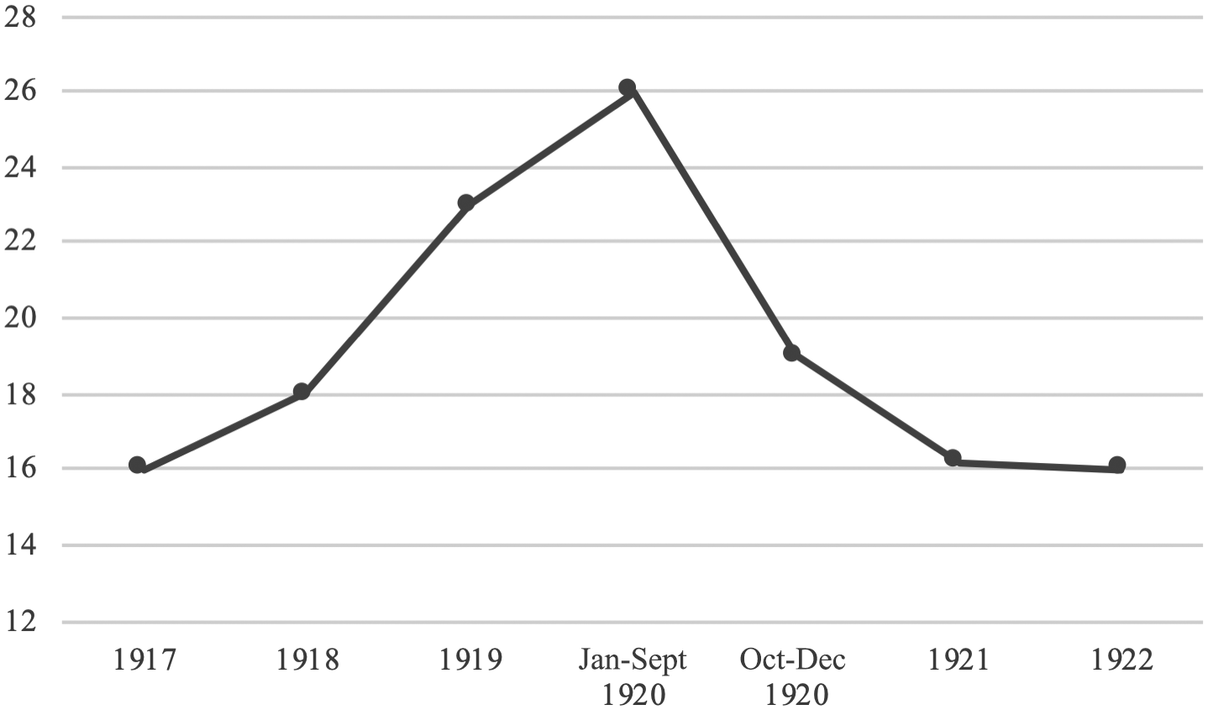

During World War I, the rate of exchange between the pound and the rupee began to shift. Figure 2 gives the value of a rupee in British pence over the period between 1913 and 1922. It shows the sharp appreciation of the rupee against the pound over the period from 1918 to 1920, when rising silver prices drove the value of the rupee upward. The impact of the rupee’s appreciation against the pound was unevenly distributed between different communities and interests in East Africa. On one side were European settler farmers, who exported much of their produce to Britain and therefore received the proceeds in pounds. However, their local expenses for paying wages or servicing debts were figured in rupees, and thus the appreciation implied a dramatic decrease in the local value of their income. On the other side were Indian merchants and African wage-earners, whose incomes and savings were calculated in rupees. Also on this side of the debate were British and imperial banks operating in East Africa, which had advanced rupees to settler farmers and intervened forcefully to avoid any decrease in the value of these assets. These distinctions linked the crisis firmly to wider debates about racial policies in the region (Maxon Reference Maxon1989; Mwangi Reference Mwangi2001; Pallaver Reference Pallaver2019).

As in The Gambia, policy fights over what to do about the shift were protracted, and proposed solutions struggled to keep up with a rapidly changing economic situation. The first proposal, in December 1919, was to establish an East African rupee, distinct from the Indian rupee, with a fixed value of two shillings (or 24 pence). This solution pleased no one. Indian merchants were unhappy that the proposed fixed value of the East African rupee was below that of the Indian rupee, then two shillings four pence. At the same time, the British settlers were dissatisfied with the increase in their local expenses relative to pre-war years.

Still, in April 1920, the newly established East African Currency Board began to issue an East African florin equal to one rupee and two shillings. Shortly thereafter, however, the value of the rupee began to fall, and by 1921 it was back at its pre-war exchange rate with the pound. This gap between the international market value of the rupee and its fixed rate in East Africa led to the large-scale importation of rupees by traders who would use rupees to purchase pounds at the rate of ten rupees to the pound in East Africa and then exchange them again at the Indian rate of fifteen rupees to the pound elsewhere, thus reaping substantial arbitrage profits (Pallaver Reference Pallaver2019:6; Mwangi Reference Mwangi2001:776).

These changes led to renewed pressure for a new solution. The colonial government suspended the import of rupees but smuggling continued, and in February 1921 the government demonetized the rupee with little notice. This led to protests from all the communities involved, with the colonial government acknowledging, particularly with regard to African wage-earners, that “it is probable that in some cases genuine hardship has been caused to natives by the demonetization of the Indian one rupee note.”Footnote 11

In the same month, the Kenya Currency Committee agreed that the colony would switch to the East African shilling, which was issued at par with the British shilling. The shift to the shilling resolved problems created by the changing value of the rupee, but it also created a new set of issues around minting new coins and redeeming the currency already in circulation. One proposal was to devalue the existing one-, five-, and ten-cent florin coins to shilling cents, which would have cut their value in half (Pallaver Reference Pallaver2019:7). This, in effect, would have made Africans—who were the primary users of small-denomination coins—pay the costs of the currency change, rather than the colonial governments of the region or the EACB (Maxon Reference Maxon1989:340). This plan was eventually quashed after a chorus of protests, which included questions raised in Parliament and an article by Leonard Woolf in the New Statesman and, perhaps most convincingly, a memo by the governor of Uganda on the potential impact such a move would have on the purchase of cotton, which was then East Africa’s leading export (Pallaver Reference Pallaver2019:8–9).

The switch to the shilling thus occurred over a longer period, with the opportunity offered to redeem rupee and florin coins. This proved to be a slow and costly process. The Board’s 1922 annual report noted that “considerable quantities of Indian rupees still circulate amongst the natives of the Coast locations.” In Uganda, “local difficulties which are not of easy solution” delayed the closing of the redemption account. The Board estimated that at least 2.5 percent of the rupee notes still in circulation would never be returned. Even in 1925, the Assistant Currency Officer in Mombasa reported that there was still “a steady influx” of old rupee and florin notes into the district treasury, and rupee and florin coins were “still in general use throughout the whole of Kenya and Uganda,” particularly outside urban areas.Footnote 12

Read alongside the history of the crisis in The Gambia, the parallel crisis of the rupee in East Africa offers a new perspective on the history of colonial monetary policies and the “currency revolution” debates. First, colonial policies in this area were not uniform, and there were numerous debates and inconsistencies which influenced the development of colonial monetary systems. The continued acceptance as legal tender of the French franc and the adoption of the rupee in East Africa even as other policies attempted to strengthen economic ties with Britain rather than India are two examples. These inconsistencies were of limited consequence under the stability of the pre-war gold standard but later would create costly confusion. Second, colonial policies were not monolithic, but rather shaped by disputes between different interest groups, which were brought into sharp relief in the East African crisis in particular. Third, long-standing African traditions of finding value in the mediation between currencies were readily adaptable to the uncertainties of the interwar period. Finally, disputes over currencies in Africa were not just about the retention of precolonial currencies over the introduction of new ones, but rather reflected wider developments in the global economy, including, as will be explored in the next section, the relative economic decline of the imperial powers over the course of the interwar period.

From Sterling to the Dollar in Liberia

The French five-franc coin was not the only European or colonial currency to circulate beyond the territorial limits of a particular colonial state. British West African shillings did so, as well. From the late nineteenth century, British currency—and, after 1912, British West African currency—also circulated in independent Liberia. When the British pound began to depreciate against the US dollar, however, both Liberia’s merchant elite and its government were vulnerable to significant financial losses. The impact on government finances in particular threatened significant upheaval in Liberia until it managed to switch to the US dollar with the financial assistance of the US government in 1943 (Gardner Reference Gardner2014).

One question in the study of colonial monetary systems is to what degree the policies adopted by colonial governments were driven by metropolitan pressure or by the broader pressures of globalization. Unlike the other two governments discussed here, Liberia was not formally colonized by any of the major imperial powers. Liberia was established in 1822 as a colony for freeborn African Americans, but it declared independence in 1847 in order to tax the growing coastal trade. The Liberian economy enjoyed a brief period of prosperity linked to that trade during the first two decades following the declaration of independence, but then suffered a long period of economic stagnation from the 1870s until the 1930s (Gardner Reference Gardner2022).

Liberia’s more limited access to capital provides one explanation for this stagnation. From the beginning, the Liberian government had struggled with the terms of its integration into the international financial and monetary system. After 1847, Liberia’s first president argued for the creation of a new Liberian currency, “for the conveniences of trade,” and to “mark the existence of the nationality of the republic.”Footnote 13 This new currency, the Liberian dollar, though nominally pegged to its American counterpart, was an unbacked paper currency. Its value relative to other currencies ultimately fell victim to the fiscal weaknesses of the Liberian government. By the early 1860s, the Liberian treasury had begun to issue unbacked paper to pay military wages and other government expenses. In his second inaugural address in 1866, President Daniel Warner referred to “an immoderate expansion of paper currency notes, which had resulted in severe monetary distress upon the whole country.”Footnote 14 These notes took a variety of forms, and included bills issued directly by the Secretary of the Treasury, which were used to pay European merchants for goods at below par value, who then returned them to the government in payment of customs duties at par. They also included what one British trade report described as “lithographed papers, issued in the form of banknotes and drawn upon the treasury,” which only realized around a third of their face value.Footnote 15

These issues of paper money resulted in the depreciation of the Liberian dollar relative to sterling. As Britain was at that point Liberia’s main trading partner, this depreciation made it increasingly difficult for Liberian merchants and others to purchase imported goods. It also increased the costs to government of servicing Liberia’s public debt, denominated in sterling during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Liberian government had raised its first loan of GBP100,000 in London in 1871, though on terms so onerous that it went immediately into default and remained in default until 1899. It raised a further loan of GBP100,000 in 1906 with the intention of funding the establishment of a rubber plantation (Gardner Reference Gardner2017). Neither loan achieved its stated goal, and they left the Liberian government with little to show other than an accumulating set of obligations denominated in sterling. As a result of the pressures of both trade and public debt, first Liberian merchants and then the government began to use British sterling as the primary medium of exchange—first in the form of the sterling coins circulating widely in British West Africa, and then from 1912 through the use of British West African shillings.

At the same time, however, Liberia’s economic ties to Britain began to weaken in favor of the United States. In 1912, the Liberian government raised a third loan—the so-called “refunding loan,” which was intended to redeem its previous obligations. This loan was denominated in dollars. In addition, the terms of the 1912 loan had stipulated the creation of a Customs Receivership and the employment of an American financial advisor and military advisor (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2007:75–76). Their salaries were also denominated in dollars.

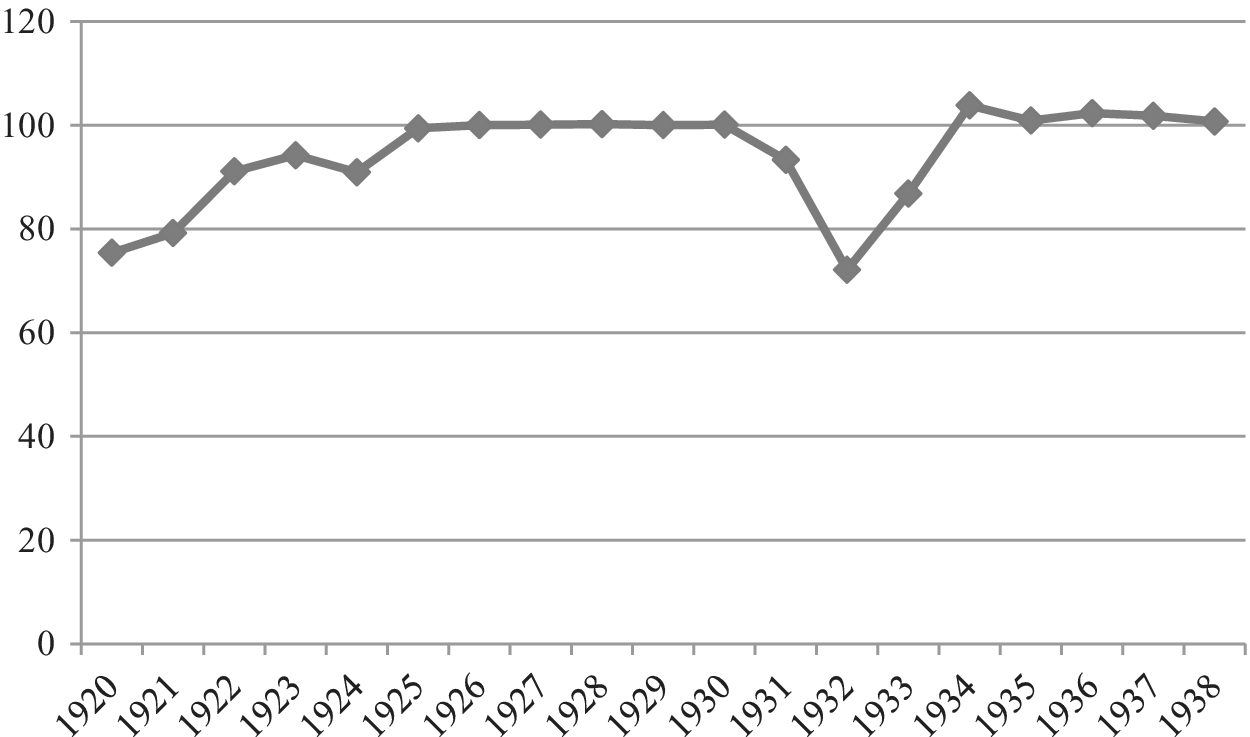

As in the previous cases, the mismatch between the currency in which the Liberian government collected its revenue—sterling—and the currency in which its debts were denominated—US dollars—was not an issue so long as exchange rates remained stable. However, once sterling began to depreciate against the US dollar, this increased the costs of servicing the debt substantially. Figure 3 shows the pound-dollar exchange rate over the course of the interwar period.

Figure 3. Pound-dollar exchange rate (1929=100)

Source: Dimsdale (Reference Dimsdale, Eltis and Sinclair1981)

The combination of the dollar’s appreciation and the additional costs of foreign financial controls pushed the cost of servicing external debt up to as much as 50 percent of total revenue during the periods of sharp depreciation in the early 1920s and early 1930s. Because the terms of the loan gave the Liberian government very limited control over its own funds, much of its revenue being managed by foreign financial advisors, little remained for other government obligations, including the payment of government employees. One result of this crisis of the public finances was the institution of policies allowing local officials to claim payment for taxes and other local obligations in goods or labor, contributing to a series of practices later investigated by the League of Nations (Gardner Reference Gardner2022).

As numerous observers noted over the years, the obvious solution was for Liberia to shift to using the US dollar as its primary currency instead of sterling. This was the recommendation, for example, of “money doctor” Ernst Kemmerer, who was commissioned to write a report on Liberia’s monetary system in 1939.Footnote 16 However, the costs of such a change, in terms of both buying up existing coinage and then replacing it, were prohibitive. According to US officials, these costs were estimated to be between USD100,000 and 150,000, which, as the charge d’affaires wrote in 1942, “Liberia does not have available for this purpose.”Footnote 17

In the end, the costs of the switch became part of the US war effort. Starting in 1942, the US began to station troops in Liberia for purposes of supporting the air campaign in North Africa. A letter from the State Department to the US legation in Liberia noted that “the appearance of American forces in Liberia will immediately present an important commissary and paymaster problem. The War Department has expressed a desire to introduce, if possible, American currency for local expenditures and salary payment.”Footnote 18 In the end, US dollars were flown in by the US military and exchanged for sterling silver coins and British West African currency, which was then shipped to the West Indies and Sierra Leone, respectively (Gardner Reference Gardner2014).

Contemporaries saw this shift as a symptom of wider global changes. According to a Federal Reserve of New York press summary, for example, Liberia’s currency change was “believed to foreshadow the emergence of the dollar as an international currency… Dollar exchange is steadily replacing the pound sterling as an international currency exchange.”Footnote 19 In other words, it reflected shifts not only in Liberia’s economy, but also in the world as a whole. For Liberia, the shift was not always positive. It resolved the currency mismatch problems of the interwar period. However, it may have had perverse effects on trade. After the war, dollar shortages among European countries which had traditionally been important trading partners for Liberia prevented many from buying Liberian products, perhaps serving to consolidate Liberia’s dependence on the United States. As the post-war decades were a period of rapid economic growth for Liberia, this impact may not have been perceptible to many Liberians. More obvious is the fact that even in the twenty-first century, the US dollar remains Liberia’s primary medium of exchange (Gardner Reference Gardner2022).

Conclusion

In his classic history of financial crises, Charles Kindleberger (Reference Kindleberger2005) describes the topic as a “hardy perennial” in research on economic history. Though individual crises are rooted in their specific historical contexts, Kindleberger argues that comparisons between crises (in his case, over time and across space) could yield broader insights into a general theory of why financial crises happen. In this article, a comparison between three crises in African economies generated by interwar instability in the value of metropolitan currencies provides a different perspective on the creation of colonial monetary systems. Most histories of colonial monetary policy focus on the early period, when colonial governments attempted to impose uniform currencies on economies which had developed around the mediation between different types of currency. Their limited success was one indication of their limited control over local economic dynamics—one of many such indications, as subsequent work has shown.

Frequently neglected in this work is the fact that the metropolitan governments themselves were struck with a series of monetary crises, beginning with the abandonment of the gold standard during World War I. How and to what extent this metropolitan instability was propagated to colonial economies has yet to be investigated fully. The three crises examined here show that interwar monetary instability did have a significant impact on colonial economies, an impact that was exacerbated by early inconsistencies in colonial monetary policies such as the continued circulation of the franc or the adoption of the rupee. In both The Gambia and East Africa, colonial governments took several years to adopt new monetary policies in response to changing global conditions, despite incurring heavy financial losses resulting from the delay. This struggle to respond effectively contrasted with the speed with which African, Syrian, and Asian merchants took advantage of the arbitrage opportunities offered by fluctuating interwar exchange rates.

The case of Liberia shows that these struggles were not restricted to colonial governments, and that informal influence could also bring African governments into the crises of the interwar period. Liberia, though independent, had come to adopt British sterling as its primary medium of exchange for official transactions due to the depreciation of the Liberian dollar. In time, however, the rise of US dollar diplomacy led to the shift in Liberia’s government debt from sterling to the US dollar. The depreciation of sterling then made it difficult for the Liberian government to service its dollar-denominated obligations with revenue raised largely in sterling.

This is not yet a comprehensive history of interwar monetary instability in Africa. There is much more to be said about the three cases profiled here, as space constraints preclude more detailed treatment. In particular, it remains challenging to locate direct evidence of African responses to colonial monetary policies (Pallaver Reference Pallaver and Pallaver2021). Other similar crises are equally deserving of attention. There has been a welcome effort recently, for example, to bring South Africa into the global history of the Great Depression and the interwar gold standard (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2021). Tensions between regional and imperial economic links in the Rhodesias provide similar stories. What this study has aimed to do is to show that a comparative approach to the currency crises of the interwar period can provide greater insights into the workings of colonial monetary policies during the period than the treatment of individual crises in isolation from one another.

It also shows that some of the crises that have afflicted post-independence African governments—currency depreciation, the repayment of public debt, and the challenges of dollarization—are not new. Another strand of literature on Africa’s monetary history focuses on the decolonization era and the ways in which post-independence states responded to some of the same dilemmas facing early colonial states (see, eg, Schenk Reference Schenk1997; Stasavage Reference Stasavage2003). Africa’s history should thus be part of global histories of monetary instability, not merely as a victim of colonial machinations but as part of a history of how people with different histories and traditions have responded to processes of global change. As Jane Guyer writes, paraphrasing Karl Marx, “People make their own history, albeit not under conditions of their own choosing” (Reference Guyer2004:5).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their comments. The article also benefited from the feedback of Michiel de Haas, Gerold Krozewski, Toyomu Masaki, Maria Eugenia Mata, and audiences at the ASAUK conference in Cambridge.