In the early 1880s, a witness before the Royal Commission on the Employés in Shops and Factories in the colony of Victoria, Australia, provided a report of statements from workers in the printing workrooms of newspapers:

boys of the most tender years are employed at excessive and unreasonable hours […] and they are compelled to work every night in the week […] from three or four in the afternoon till about three the following morning […] in a room filled with impure air and lighted gas.Footnote 1

Whether child labour is viewed as a problem depends on the norms of society. During industrialization, the employment of children in factories provoked great contemporary concern. Few aspects of the Industrial Revolution in Britain have received quite so much attention as the child workers of the “dark satanic mills”. Studies identified the core characteristics of the problem: the young ages of the children, the harsh circumstances of their work, and the extensiveness of their employment.Footnote 2 Lord Ashley (from 1851, the Earl of Shaftesbury) has long been celebrated as the Tory champion of child workers for his successful support of British legislation that restricted the employment of children in factories.

There is ongoing controversy, however, about the role and regulation of child labour within broader debates on the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 3 It has generally been accepted that children worked in factories in the early stages of industrialization, not just in Britain, but also in the United States (US), Canada, and Europe. Yet, there are differences in opinion about their employment as industrialization proceeded.Footnote 4 Nardinelli contended that advancing technology reduced the demand for children and so legislation to restrict child labour did not encounter great opposition. In contrast, both Tuttle and Humphries, though presenting different accounts, concluded that children continued to be employed in factories because advancing industrialization created jobs for which they were particularly suited. From the perspective of reformers, therefore, legislation was required to protect children.

While most research has focussed on Britain, a series of articles by Bowden and colleagues examined the employment of children during industrialization in Australia.Footnote 5 By the mid-nineteenth century, Australia had been transformed from a British penal settlement into six colonies. Following the major gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s, industrialization advanced rapidly. Most recent estimates show that Australia grew into its leadership position of the world's economies by the 1870s, maintaining this position for the next two decades.Footnote 6 Bowden and Stevenson-Clarke conducted a study of child labour in the colony of Queensland at the end of this period. Their findings support Nardinelli's viewpoint. They concluded that employers chose to hire skilled adult workers in preference to less productive children. They believed that the child labour problem in Australia was comparatively modest and confined to a restricted number of industries. Thus, there was little need for regulation, and, in their view, the factory acts passed in the colonies of Victoria (1885) and New South Wales (1896) were “pale imitations of their British counterparts”.Footnote 7

In this paper, these academic debates are considered by an investigation of child labour and its legal regulation during industrialization in a different colony of Australia. In contrast to Bowden's studies, which examined all industries in Queensland, where primary industries predominated, this research investigates child factory labour in Victoria, the most populous of Britain's Australian colonies and the leader in manufacturing. Consistent with changing views of childhood in late nineteenth-century Victoria, persons up to the age of fifteen are investigated.Footnote 8 This study is confined to the children of white settlers. After the first British settlement in Australia in 1788, the population of the indigenous peoples was drastically reduced, mainly through disease spread from the colonists. It has been estimated that numbers in Victoria fell from 60,000 in the 1790s to around 1,900 in 1850.Footnote 9 Following the arrival of the British in Victoria in 1834–35, the colony's indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their traditional lands. By the early 1850s, the Kulin people had been pushed out of what had become central Melbourne and confined to remote mission camps.Footnote 10

Three research questions are addressed. Was there a child factory labour problem in Victoria according to the norms of the colony as industrialization advanced? Was the Victoria child labour legislation of 1885 a “pale imitation” of its British counterpart? The relevant comparison is the British Factory and Workshop Act of 1878, a valuable benchmark because it consolidated and replaced a series of earlier nineteenth-century British factory laws. Was the legislation passed through employers’ indifference or through the efforts of liberal reformers? Three sources of textual primary data are investigated. These comprise reports and minutes from the Royal Commission on the Employés in Shops and Factories (1883–1884), the bills and statutes to regulate child factory labour (1873–1885), and the parliamentary and public debates that surrounded the eventual successful passage of legislation (1885). Addressing the research questions by an examination of these primary sources helps inform the academic debates by investigating the existence of child factory labour in several ways: through a direct study of the Commission's investigation of children in factories, by an analysis of the protective statutory measures deemed desirable by reformers, and by an appraisal of the level of support for and opposition to the regulatory measures.

This study considers the academic debates. It moves on to present the context of Victoria in the later nineteenth century, then investigates the primary data. The findings are compared with the results of studies of the “home country” of Britain and the British settler colony of Canada. The academic debates are reconsidered in the light of the results.

CHILD LABOUR AND INDUSTRIALIZATION: THE ACADEMIC DEBATES

The controversies about child labour in the Industrial Revolution concern its existence after the early years of industrialization and initially were confined to the textile industry in Britain.

Nardinelli maintained that machinery was operated by adults throughout industrialization and that children were never used as substitutes. Children were employed in the early stages because they could carry out certain tasks efficiently at a lower cost than adults. They performed secondary tasks such as picking up waste cotton and piecing together broken threads. As technology moved to steam power, there was less wastage and breakage and, correspondingly, factory demand for children was reduced. Further, while children were sent to work because their families were poor, as industrialization proceeded, growing real income lowered their supply. Consequently, a fall in child factory employment was already taking place before the first enforceable British factory act (1833). The Factory Acts, then, did not cause the long-run decline in child labour. Indeed, they may have been “more an effect of the decline than a cause” as opposition by business interests was no longer strong.Footnote 11 This viewpoint has been lent support by Kirby's analyses of 1851 British census data, which show a low incidence of child factory labour, not just in textiles but across industries.Footnote 12 The importance of child labour legislation is thus questionable.

In contrast, Tuttle concluded that child labour persisted throughout the Industrial Revolution. The crux of her explanation is that factory production benefitted from the distinctive age-related advantages brought by children. It was the “high energy, quickness, watchful eyes, nimble fingers and docility of children” that were suited to factory work, and the small size of their bodies that allowed them to fit in cramped spaces.Footnote 13 These features made children desirable to employers throughout industrialization. As technology developed alongside a division of labour, it created many simple one-step tasks that required such characteristics. Ongoing industrialization, therefore, increased work opportunities for children. Children were employed, not just as helpers, but as primary workers, assisting adults, tending some machines and operating others. For Tuttle, children could work in the factory, at home, and/or go to school. By lowering the financial returns from working, legislation could act as a deterrent to parents choosing to send their children to the factory.

Other scholars have investigated a range of industries. In her recent study of Britain, Humphries concluded that child labour, including factory work, persisted but from a different perspective. For Humphries, children played a central role in ongoing industrialization: the “industrial revolution […] retained at its heart and pulsing through its life-blood this shameful feature”.Footnote 14 But rather than creating jobs that suited the age-related characteristics of children, she argued that the very detailed division of labour created low skill, casual, and irregular work in which children were employed because they were cheap substitutes for adult males. Unlike Tuttle, she also emphasized the importance of poverty in supplying children to factories throughout industrialization. She presented growth and wage figures that were lower than previously estimated and not universal. Further, when more costly male breadwinners became unemployed, families sent their children to work. Humphries maintained that comparison of census figures with other records in Britain has shown that the former underestimate the extent of child labour. She analysed 600 memoirs of working men and found evidence of the widespread employment of boys across a wide range of industries. She noted the lack of protection for children before factory acts were passed. In such a situation, legislation to regulate the employment of children regains its importance.

Studies of US industrialization also present both sides of the debate. Hindman contended that the low productivity of child workers was tolerated during the early years of industrialization in a transition period. Like Nardinelli, he argued that, as industrialization progressed, capital investment in mechanization required returns from the high productivity of skilled adult male workers so children were no longer required. Other US research, however, provides support for Humphries. Goldin and Sokoloff's study of manufacturing in the North East of the US during industrialization up to 1850 found an organization of work that involved a separation of tasks with low-paid work associated with the substitution of women and children for adult men.Footnote 15 Further, from analyses of US census data, Gratton and Moen found parental poverty made an important contribution to the supply of child workers in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 16

Finally, Canadian research identifies themes very similar to those of Humphries.Footnote 17 For Hurl, children were “a viable, and for some industries even necessary component of the work force in later nineteenth-century Ontario”.Footnote 18 By 1871, extensive mechanization was accompanied by a division of labour, with lower-paid, less-skilled fragments.Footnote 19 Children were hired as cheaper substitutes for male adults in these jobs. There was a ready supply because of the poverty of some families. Hurl reported estimates showing it was not until the 1890s that the lower rank of workers in Ontario improved their economic position “relative to the more affluent”.Footnote 20

CHILD LABOUR DURING INDUSTRIALIZATION IN AUSTRALIA

These academic debates are considered in relation to the colony of Victoria, Australia. Industrialization advanced in Australia from the middle years of the nineteenth century and grew rapidly out of the British Industrial Revolution. Though on a much smaller scale, it was based on British transport, machinery, and ideas brought from the home country; mechanization processes relied on technology freely imported from Britain; entrepreneurs arrived from Britain; and technological knowledge was gained from contacts and visits to Britain.Footnote 21

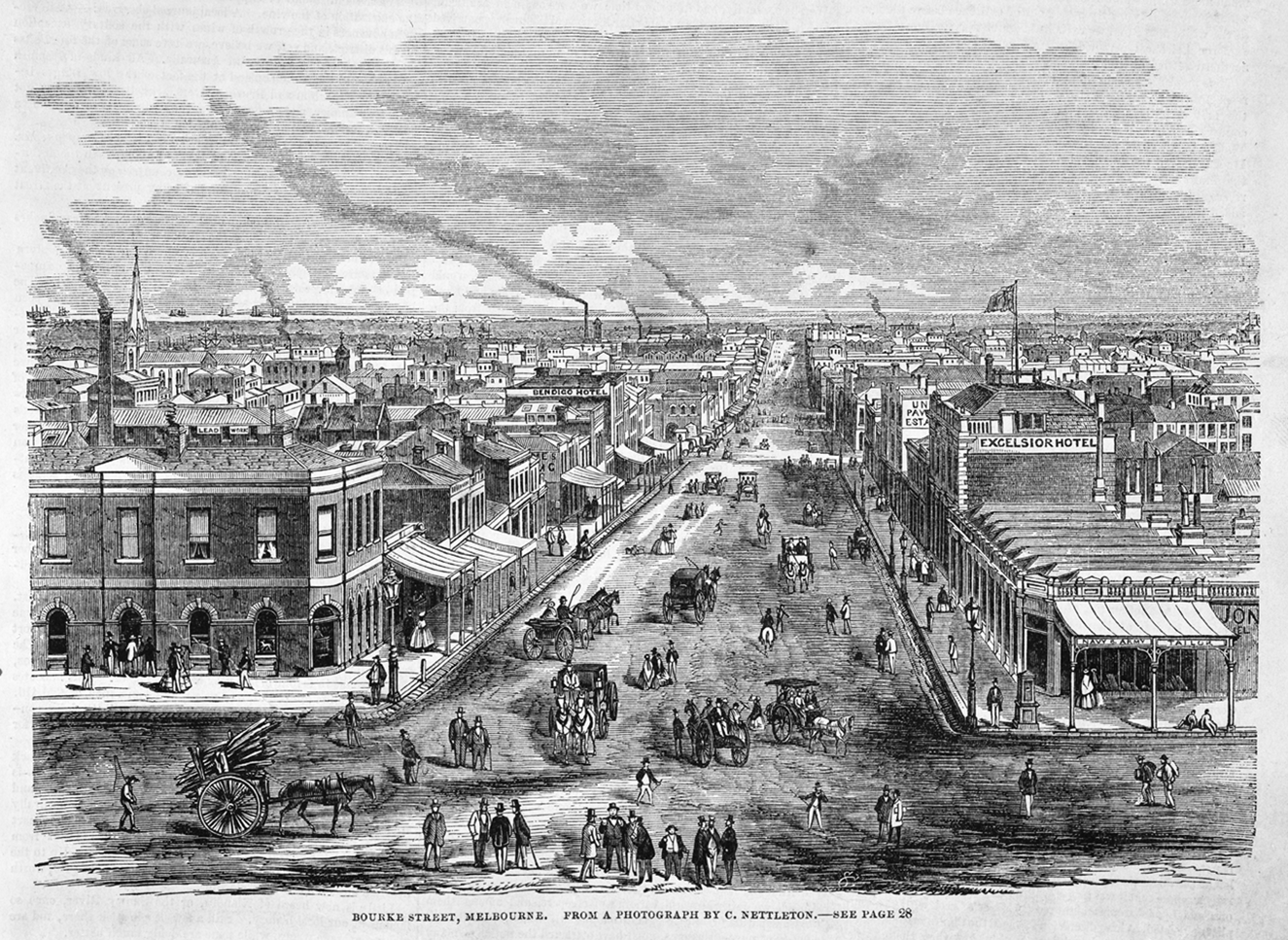

The major discoveries of gold, starting in the 1850s in Victoria and New South Wales, led to waves of immigration. It was conventionally held that the gold rushes brought about a period of sustained growth in the newly-constituted colonies: the “long boom” (1861–1890). Fox concluded that, while most prospectors who returned from the goldfields from the early 1860s onwards were initially “disappointed and despondent,” they gained work easily: “the picture emerges of a nineteenth-century paradise of the south-west Pacific”.Footnote 22 Victoria grew to become the most populous and industrialized of the Australian colonies and was especially held to “possess advantages which make Australia a workers’ paradise”.Footnote 23 By 1854, Melbourne was the largest city in Australia. Using census figures (which likely underestimate actual figures), Sleight reported an eightfold increase in Melbourne's population during the 1850s and 1860s.Footnote 24 A photograph of a wood engraving of Melbourne in 1862 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Bourke Street, Melbourne (with factories), 1862. Photograph by Charles Nettleton of wood engraving by Samuel Calvert, The Illustrated Melbourne Post, April.

State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/128428

“Marvellous Melbourne” fast became larger than most European cities and the second most populous city in the Empire after London, its population reaching nearly half a million in the 1880s. It has been estimated from contemporary accounts that, by this time, half the industrial workforce in Melbourne was employed in factories and workrooms and, of these, half worked in factories that employed more than fifty workers.Footnote 25 One result was the growth of trade unions, initially for skilled workers. In Melbourne, the eight-hour day was achieved by stonemasons in 1856 and the Melbourne Trades Hall Committee (THC) was established. Subsequently, the eight-hour day became the “principal union rallying point”.Footnote 26

According to Sleight, this period witnessed the first “baby boom” in Australia as the settlers raised families.Footnote 27 In 1881, half the population was under twenty-one years and a quarter between five and fifteen years with the largest concentration of children living in Victoria, especially Melbourne.Footnote 28 The image painted of “Young Australia” in many narratives of visitors to Australia was of a child who was “fat, contented, lucky, soft and untried”. An example is shown in Figure 2.Footnote 29 Victoria's children were, in particular, said to be “overindulged”.Footnote 30

Figure 2. “Mr Foster's little child”, 1879. Photograph by Foster & Martin of a small girl (photographer's daughter) sitting in a studio beside a ‘rockpool’, 4 June.

State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/242097

British contemporary commentators blamed the distance from “civilization” and regulations about school attendance for this “sorry state of affairs”.Footnote 31 The Education Act 1872 (Vic) made school attendance free, secular, and obligatory for children under fifteen. A photograph of one of the earliest state schools in Victoria is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Photograph of children of Bacchus Marsh School (one of the first schools in Victoria, opened in 1854), Melbourne. Early 1870s.

Federation University Australia Historical Collections, https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/4f72bed397f83e03086069eb

While one nineteenth-century chronicler acknowledged that some children in Australia “find their services called into requisition”, this was not viewed to be problematic as work gave them an amusing “precocious smartness”.Footnote 32 Thus, some observers denied the need for the regulation of child workers; “labour being well able to take care of itself is […] indifferent to that legislative protection which has been thought necessary for European workers under their entirely different conditions”.Footnote 33

Research by Bowden and Stevenson-Clarke supports this viewpoint, suggesting there was sparse employer demand for child labour across most industries. Using 1891 Queensland census data, they found only small numbers of children employed in factories. Following Nardinelli and Hindman, they stressed the importance of an employer preference for hiring productive adults. They argued that “much of the nation's manufacturing sector […] required skilled and/or experienced workers” so managers chose not to hire children.Footnote 34 Thus, there was no need for restrictive legislation.

An examination of the literature, however, shows similar industrial characteristics in Australia, particularly in Victoria, to those identified by Humphries in Britain and Hurl in Canada. Lee and Fahey conducted an in-depth analysis of Australian company records from the 1870s and 1880s.Footnote 35 Manufacturers competed fiercely by cutting costs through work sub-division. Factories “bundle[d]tasks of the same skill level into discrete jobs” with low-skill jobs consisting of straightforward repetitive tasks.Footnote 36 This organization of work was important for businesses in Australia, far from the home country, as they could shed an “outer husk” of unskilled workers to respond to “a shortage of imported parts, communication difficulties with Britain, the seasonality of rural produce on which the cities were dependent, and extreme weather”.Footnote 37 Thus, a very large, casual, unskilled workforce existed, including young persons, employed as low-paid substitutes for adult males. Such work organization was particularly marked in Victoria. Further, Australia – like Britain – was not as wealthy as previously thought and there were major disparities in work experiences and wage levels, even in Victoria. Australia, therefore, was not a “paradise” for all workers. It displayed a favourable economic context for child factory labour.

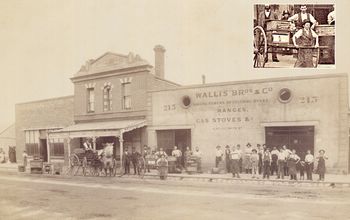

Although there are very few direct investigations of child factory workers in Victoria, from an analysis of the colony's census data (1861, 1871, and 1891), Larson concluded that very irregular school attendance “suggests that many children had some employment”, attributing seasonal truancy, in part, to “a heavy demand on children's labour at certain times of the year”.Footnote 38 She identified low numbers of children working in factories in 1861 and 1871 but reported the inadequacy of the data as the census forms made it impossible to return a child both as a worker and a student. She did not present figures for 1881 as she found the returns were too unreliable: under the provisions of the Education Act of 1872, families were discouraged from categorizing as workers children who also attended school because penalties could be imposed on parents (Section 14). Photographs of factory owners with their workforce are extremely rare, yet Figure 4 shows one such example with factory workers of a range of ages/heights. The Education Act of 1872 stated that “when any child is educated up to the standard of education required by this Act such child shall receive a certificate” (Section 20). The attire and stature of the person of small stature seems to indicate a male child worker, partly concealed in the background, perhaps because he has no certificate.Footnote 39

Figure 4. Wallis Bros & Co. factory, Melbourne. Inset: close up of child worker, c. 1884. Photograph by Charles Rudd.

State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/298694

Overall, therefore, although there are sparse studies, existing evidence shows that, from the 1860s, the economic context of later nineteenth-century Victoria provided fertile ground for the employment of children in low-paid, unskilled, unstable factory work.

Yet, Victoria also provided a political context favourable to child labour reform. As a result of the timing of the arrival in Victoria of the British free settlers in 1834–35, liberalism was the dominant orientation in this period.Footnote 40 The roots of colonial liberalism lay in British liberal traditions of electoral reform. Victoria gained its own constitution in 1855, followed shortly after by universal male suffrage and – leading the world – the secret ballot. From the late 1860s, the bulk of the Legislative Assembly had liberal sympathies.Footnote 41 The settlers had come to Australia to find a better life and, for colonial liberals, it was self-evident that “the New World offered opportunities for moral and physical development beyond anything available to the stunted inhabitants of industrial Britain”.Footnote 42 Liberals in Victoria “moved easily from the welfare of the individual to the welfare of society” and colonial liberalism was characterized by social liberalism: an ethos of social responsibility, notions of equality of opportunity, and an expanded role for the state.Footnote 43 State intervention in Australia owed much to geographical remoteness, origins as a convict prison, the scale of primary industries, and limited access to capital. Footnote 44

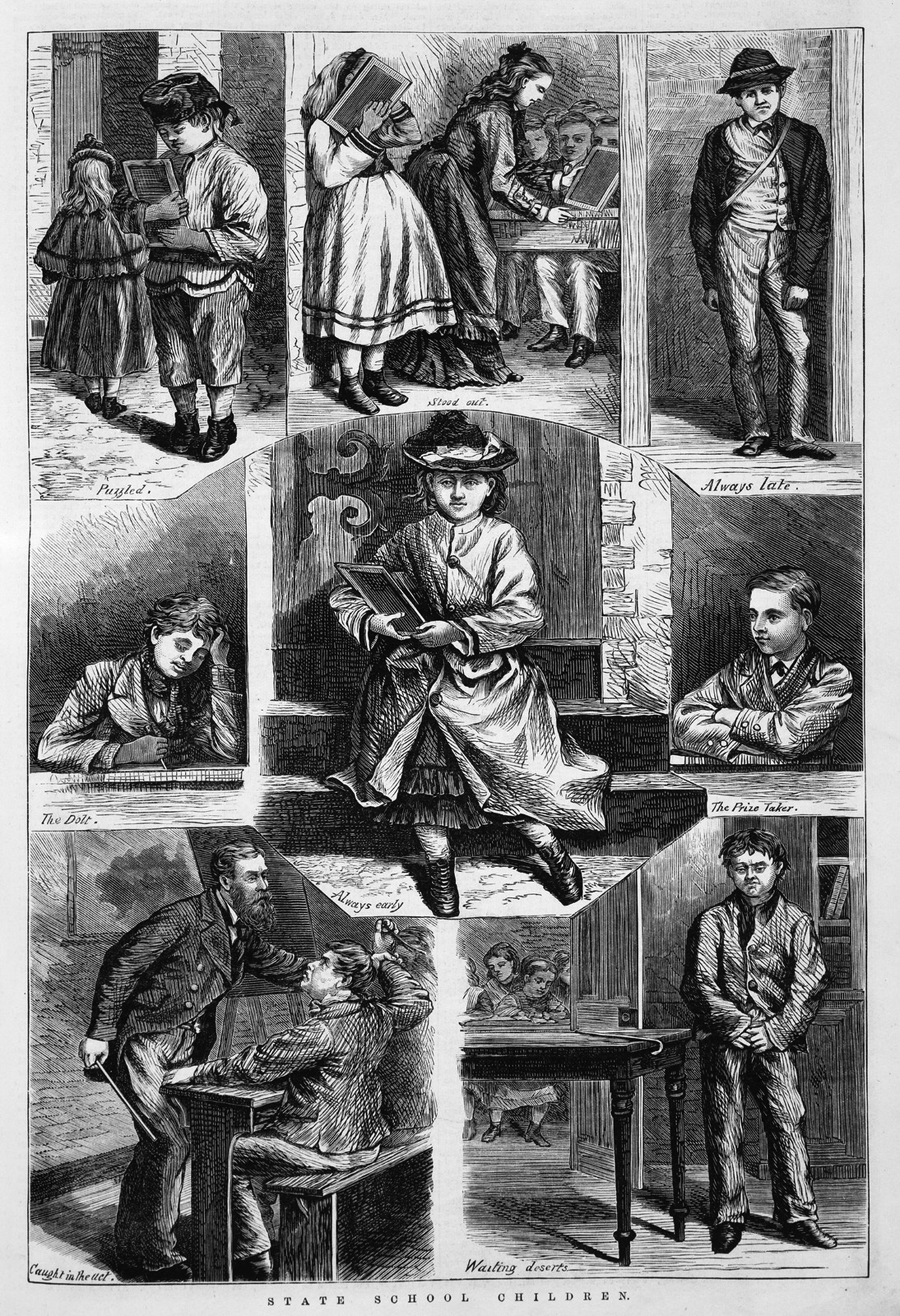

Colonial liberals, therefore, adopted a stronger interventionist stance than liberals in Britain. The state was given a “new role as the instrument and protector of the material well-being of its citizens”.Footnote 45 Regulation was passed to pursue the liberal tradition as “a march of material and moral progress […] conferring universal benefit through the enhancement of individual capacity”.Footnote 46 Factory and education laws were part of a coherent colonial liberal programme: factory legislation to remove children from the physical and moral harm of the workplace; education reform to send them to school, embodying the prevailing liberal ideal that careers were “open to talent”.Footnote 47 Figure 5 shows an image of a wood engraving of different images of schoolchildren.

Figure 5. “State School Children”, 1878. Eight images in one wood engraving (“Puzzled -- Stood out -- Always late -- The dolt -- Always early -- The prize-taker -- Caught in the act -- Waiting deserts”), The Illustrated Melbourne Post, 13 May.

State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/73837

For Alfred Deakin, the leading liberal politician in Victoria and later the second prime minister of Australia, “a Colonial Liberal is one who favours state interference with liberty and industry at the pleasure and in the interest of the majority”.Footnote 48 The charismatic young Deakin was “a tall, thin, handsome young man […] vivacious and eloquent”, the “driving force for factory reform”, and the “pivot for colonial liberals in Victoria”.Footnote 49

The research questions concerning whether, in this context, child factory labour was considered problematic, the character of the bills and statutes, and the response of business interests are considered by the following analyses of primary source material.

THE ROYAL COMMISSION ON THE EMPLOYÉS IN SHOPS AND FACTORIES

From the early 1870s, drawing on British precedents since 1816, liberal politicians had made calls for a Royal Commission to enquire into conditions in factories, including child employment. The Royal Commission on the Employés in Shops and Factories, with Deakin as one of its Commissioners, was established in Victoria in 1881. It conducted its enquiries over the following two years, making a series of reports to parliament.

The Commissioners paid visits to factories (large establishments) and workrooms (small establishments) in Melbourne, its metropolitan suburbs, and the smaller urban centres of Ballarat and Geelong. They visited over seventy establishments (employing up to 350 workers) where a wide range of industries was represented across broad categories including food, drink and tobacco, clothing and footwear, and household goods. Child workers were observed in almost all these industries. The first column of the Appendix lists the industries in which children were observed.Footnote 50 The Commissioners’ arrived unannounced in order to form “a correct opinion of the actual state of things prevailing”.Footnote 51 The Commission took evidence from witnesses including owners, foremen, and workers. Children (up to fifteen years) were reported in almost all the establishments. Over thirty child workers in the factories were approached and other young persons provided statements of personal experiences of working in factories when they were children. The Commission also interviewed medical practitioners, magistrates, a variety of the colony's inspectors, union delegates, representatives of the Chambers of Manufacturers and other functionaries. One of their major sources of information was the truancy officers, established by the Education Act of 1872 (Section 30) (and appointed in 1877), responsible for observing and recording, not just truancy, but the ages, activities, and workplace conditions of children who absented themselves from school. While six trade unions sent their own delegates, most unions allowed the Melbourne Trades Hall Council (THC) to represent their interests.Footnote 52 The THC set up a sub-committee that examined witnesses and held two conferences with the Commissioners. The Commission operated in “hearty cooperation” with the THC.Footnote 53

The Royal Commission clearly identified a child labour problem. It summarized its findings as follows:

many abuses […] have crept into the system of regulation of the factories and workshops of this colony; abuses which have done so much towards ruining the intellectual and moral faculties of the youth of this colony. […] That the necessities of the young have been cruelly ignored has been very clearly demonstrated by the evidence of every witness examined.Footnote 54

With regard to age, there was ample evidence that the employment in factories of children of eight and nine years old, and sometimes younger, was widespread: a “large number of very young children [are] employed in factories and workshops (sic) in almost every trade throughout the colony”.Footnote 55 A truancy officer reported finding sixty under-age children in factories in the previous three weeks.Footnote 56 The foreman at a glass factory stated that they “took them […] at any age we can get them”.Footnote 57 A foreman in the clothing industry said that, “I should say, judging from their appearance, they look to be about ten or eleven but, on questioning one or two of them, I found they were barely nine years of age”.Footnote 58 Another truancy officer cautioned a mother who said her children found working in a factory were “seven years and three month […] eight years, ten months, and one twelve years”.Footnote 59

Further, both owners and truancy officers explained that it was a common and widespread practice for children to lie about their age: children “state wrong ages generally, and many of them are put up to it by their parents”.Footnote 60 One example given by a truancy officer was as follows:

in one place I went […] a youngster about the height of this table, said he was eighteen years of age. I said, “Eight or ten, my boy, you mean”. he said, “No, eighteen”. “Who told you that?” “My mother, and she ought to know” and that shut me up.Footnote 61

Children in a preserving factory reported their current ages as twelve, thirteen, and fourteen years.Footnote 62 However, the Commissioners reported that “they almost invariably stated they were thirteen years of age, although, judging from appearances, they were not more than ten years”.Footnote 63 Children were reluctant to provide information to the Commission. A fourteen-year-old in a jam factory was asked how long she had worked in the establishment and responded: “I do not know”.Footnote 64

From the outset, the Commission was obstructed in its enquiries by employers. The majority insisted that they did not take children under the age of fifteen (those under fifteen were required to attend school).Footnote 65 A foreman in a brush factory asserted that their youngest worker was sixteen but, in the same visit, the Commission interviewed six of its child workers who stated ages ranging from thirteen to fifteen years (and they may have been even younger).Footnote 66 There was other evidence that employers were wilfully deceptive. “When a truant officer was expected, they (children) were told not to come to work. When he arrived unexpectedly, he was detained until they could be snuck over the back fence”.Footnote 67 A number of employers maintained that children younger than this age were of no use to them, as they were not reliable workers. The principal manager of a tobacco, snuff, and cigar factory stated that “[i]f you leave them to do anything they get larking”.Footnote 68 But, when pressed by inspectors, some employers conceded that they did not go to great lengths to ascertain the correct ages or level of education. A partner of a boot factory commented that: “generally we go by size, no particular age, […] but go by the boy's appearance”.Footnote 69

Factory children worked long hours for low wages. Comprehensive details about hours of work and wages were provided by most of the witnesses. Reports from both owners and workers (including children) were highly consistent across the trades. The Chairman summarized the Commission's findings: “we have it absolutely in evidence that families of children get up at daylight in the morning, get a hasty breakfast, and are at work till midnight”.Footnote 70 There were age-based wage differences in all establishments with one factory listing detailed rates for “men”, “youths”, and “boys”.Footnote 71 There were reports of an initial period of very low or even no pay. A child in the soft hat trade reported to the THC that at the start of her employment: “I gave three weeks [of work] for nothing”.Footnote 72 Children were then paid about a third of the adult male rate for a working week, the same length as adults, of between fifty and sixty hours.Footnote 73 Some children were reluctant to provide wage details to the Commissioners. When asked how much she earned, a child in a hat-makers replied: “I will not tell you what I get each week”.Footnote 74

There was widespread evidence of job fragmentation and a division of labour.Footnote 75 A union delegate reported that “we have been in factories where there are apparently a dozen classes” (that is, grades of job) when he had expected to find just two classes.Footnote 76 Children were employed in the lowest skill jobs. The owner of a clothing factory reported “the division of labour – trouser hands, vest hands, and so on” where girls carried out the low skill job of “tacking”.Footnote 77 Small establishments reported they were subcontracted by factories to conduct unskilled tasks that could be carried out by children: a bootmaker who “casts around to pick up a few boys […] in the course of a week or two [can] make them very useful in certain branches such as riveting or pegging [where] they can do as much as any man”.Footnote 78 In many big establishments, whole unskilled sections of the production process were carried out almost wholly by children (as the quote at the start of this article demonstrates). Large numbers of boys and girls were crowded in tobacco factories “with about sixty or seventy children to every twenty men”.Footnote 79 The Herald and World newspapers in 1883 had thirty boy compositors as compared with only four tradesmen in their staff.Footnote 80

The Commission found that children were employed in unskilled jobs “to secure cheapness in production”.Footnote 81 The THC reported that employers placed children in competition with those who were “thoroughly competent, and thereby the prices allowed are gradually reduced”.Footnote 82 “Those inferior workmen offer themselves for cheaper wages, and when the skilled workman goes to ask for employment […] so we suffer”.Footnote 83 A trousers hand commented: “that is the great obstacle in our trade. If they reduce our prices and we refuse to take what they offer, they put the young hands in our place”.Footnote 84 There were also many reports of children taken on as apprentices, paid little, receiving no training, then laid off at the end of the probationary period without means of earning a livelihood later in life.Footnote 85 A routine practice was to say “I have no work for you, my boy” when the apprenticeship approached the end.Footnote 86

The young ages of these children made them particularly vulnerable to the wretchedness of the Australian factory environment. The reports were rife with examples of factories where workers were “crowded into small rooms which are suffocating in summer and intolerably cold in winter”.Footnote 87 A foreman in a bootmaker's factory reported “seven men and four boys in this room, ten by ten feet […] a height of […] eight or nine feet […], no ventilation […]. Work was piled round in all directions; all the walls were smothered with cobwebs […] and they were standing knee-deep in shreds”.Footnote 88

Medical professionals evinced a strong concern for children: “in every way (factory work) damages their health”.Footnote 89 A doctor stated that:

a little girl was brought to me three days ago by her mother, a little worn-out looking thing. She had been twelve or eighteen months in a factory already, and she is only thirteen now. She is like a little old woman, pale and shrivelled, and suffering from palpitation of the heart.Footnote 90

Children who were forced to squat in cramped spaces or stand for long periods of time had problems with physical growth (such as joint diseases or curvature of the spine) and doctors testified that certain types of work affected children's growth, digestive functions, and respiratory condition.Footnote 91 In some factories, children fainted from sheer exhaustion and overcrowding on hot summer days.Footnote 92 Sanitary facilities, if existent, were limited, encouraging the spread of diseases such as typhoid, diphtheria, and whooping cough, which were often deadly for children.Footnote 93 Powered machinery was especially damaging to children and caused injuries and fatalities on an almost daily basis. For example, there was a report of a boy of twelve being dragged screaming through the rollers of printing machinery.Footnote 94 The THC sub-committee reported that:

numbers of boys are employed in many manufactories under the age of twelve years, and these boys are often put to work at dangerous machines. A boy, eleven years of age, nearly had a limb torn off through his leg slipping into the pit of a large grindstone, at which he was working; the accident was of a most painful and serious character.Footnote 95

The industries in which children were crowded were often especially damaging to physical health. The tobacco industry, which employed large numbers of children, was considered very dangerous, mainly because of the heat generated by steam pipes running through workrooms in order to sweat the tobacco away from the hands of workers.Footnote 96 Of particular concern to the Commission was the large number of children employed in night work in the printing industry, which was considered “most disastrous” to children.Footnote 97 This practice was reportedly at its worst (“evil in the extreme”) at some of the major Victorian newspapers: the Geelong Times, the Bendigo Independent, and the Herald, where observers bemoaned the “want of moral shame in some of our printers”.Footnote 98 A doctor testified that he had had “ample opportunities of witnessing the injurious effects of night-work” in The Age newspaper printing works.Footnote 99 Employers also sought to hide the worst aspects of the factory environment from inspectors. A union delegate at a bootmaker's testified that “I worked in factory myself that was never kept over clean; but they always seemed to get notice of the inspectors coming, and, of course, it was made nice and clean, and everything put in apple-pie order”.Footnote 100

The Commission also observed the effect of factory work on children's “moral” health and education. The THC sub-committee reported that:

ordinary conversation of the children was of the most filthy description, and nearly all the boys were addicted to smoking and chewing, and these habits were pandered to by some of the more unprincipled among the employers, for the purpose of inducing the youths to remain in their employ.Footnote 101

It felt that early exposure to the workplace led to moral degradation. For boys, it tended to “swell the ranks of rowdyism”.Footnote 102 The plight of factory girls was of even greater concern. A representative of the Pressers’ Union commented:

they finish up in the back-slums because they are sent into the factory amongst older girls and hear things that to older brains would not have an immoral tendency, but to such young girls as that they have […] and they meet a lot of boys; and my own experience is that in nine cases out of ten they go on the streets.Footnote 103

The Commission showed widespread concern about the mixed workplaces and sanitary arrangements: “the tendency being to add to the large amount of immorality which already exists in this city”.Footnote 104

It also lamented that, despite the provisions of the Education Act of 1872, the children interviewed were often “totally ignorant of the elementaries of state education. They scarcely knew their alphabet”.Footnote 105 A department superintendent in a japanning factory stated that “I have never found a single individual who possessed that [education] certificate”.Footnote 106 A child worker in a jute factory stated: “I am twelve years old; I have been here a year. I have never been to school”.Footnote 107

Finally, poverty was highlighted as a fundamental cause of child labour. The Commission concluded that “in the majority of instances, from sheer necessity, [children] will continue to work in the factory, although they are aware that by doing so they are undermining their health, and even jeopardising their lives”.Footnote 108 An engineer in a jute factory stated that “it is their poverty that keeps them here”.Footnote 109 There was ongoing competition for jobs. At a tinsmith's, a truancy officer reported a commonplace occurrence: “[t]he day I went there, I think there were about […] a dozen children under fifteen, and at the same time there were three or four children waiting outside wanting employment”.Footnote 110

The Commission, however, found no evidence that children were employed in factories at ages as young as three or four, as had been reported in Britain, nor did it find children employed in any industry in as great proportions as had been claimed in Britain. It reported that the “dire necessity” that compelled parents to send children to work at very young ages in Britain did not exist in Victoria.Footnote 111 Nevertheless, the major child-related recommendations were to ban the employment in factories of boys under the age of thirteen and girls under the age of fourteen, to ban from night work (other) persons under the age of sixteen, and to limit young persons not prohibited from factory work to the eight-hour day proposed for all factory workers.Footnote 112 The Commission's Final Report was strongly and explicitly influenced by the THC's more ambitious recommendations regarding age limits, hours, and health and safety, which were presented in a separate appendix.Footnote 113

PUBLIC AND PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES: THE PASSAGE OF LEGISLATION

Alongside making calls for a Royal Commission, liberal politicians had also proposed a series of factory bills that included child labour provisions. In 1873, the first legislation was passed in Victoria that addressed child factory work and one of the first factory acts in the colonies.Footnote 114 Females of all ages, including girls, were not allowed to work for more than eight hours a day in a factory (Section 3). Two subsequent factory bills (1873 and 1881) – with provisions that offered protection to both male and female children – failed to secure passage.

Following the Royal Commission's reports to parliament, two more factory bills were introduced by Deakin (1884 and 1885). The Factories and Shops Bill (Vic), 1884, lapsed the session with some members deliberately keeping it off the agenda.Footnote 115 On 17 September 1885, substantially the same version of the bill was introduced.Footnote 116 In general, it was supported in parliament by liberals and opposed by conservatives. There was also much public debate, mainly presented in newspaper columns. Under the editorship of David Syme, The Age supported the bill with The Argus against it.

The Commission's reports were a key factor in both parliamentary and public debates. In parliament, it was stated that, “in connexion with the employment of young children, the Commission found a state of affairs existing in some factories enough to make one feel grieved and ashamed at living in a country where such things could be tolerated”.Footnote 117 To bring about reform, the liberals’ main contention was that both the 1884 and 1885 bills were based on the British Act of 1878 and adapted to the conditions in Victoria. Deakin asserted that the provisions contained the “substance and spirit” of clauses in the British Act “so far as they are applicable to the circumstances and condition of this country”.Footnote 118

In response, conservatives praised the British Act. It had been proposed and supported by their Tory counterparts. During the passage of the 1885 bill, an obituary for Shaftesbury in The Age highlighted their dilemma: “more than any man [he] deserves the praise at having originated that industrial legislation in which modern Liberals see most hope for the future, and to which Conservatives are most bitterly opposed”.Footnote 119 Thus, the main contention of conservatives was that conditions were just not bad enough in Victoria to merit such a law. While the British Act was said to be “the most perfect system of industrial legislation that has been enacted in any part of the world”, they asserted that the proposed legislation was an over-reaction: “in Victoria, cruelty towards employés is an extremely exceptional thing […] I say so unhesitatingly that no other country in the world can beat us with respect to the good-will that exists between our employers and employed”.Footnote 120 In a similar vein, it was claimed that the British legislation sought to mitigate “an existing evil of gigantic dimensions which was as yet unknown in Victoria”.Footnote 121 Such views were also voiced by conservatives in the Legislative Council: conditions in the “old country”, where children worked in a “condition of abject slavery”, were “so far to the contrary” of the state of things in Victoria.Footnote 122 Further, it was a “dangerous thing to boil down, in the hope of improving, lengthy and elaborate legislation […] and to apply it to a country like this”.Footnote 123 In like manner, The Argus described the British Act as “one of the greatest monuments of legislative beneficence and ingenuity known in the world”.Footnote 124 But it also argued that the 1885 bill constituted over-legislation: “the unwisdom of enthusiasts is that they see a hard case and proceed to legislate wholesale on that basis. One man gets drunk, and all the world must be deprived of wine”.Footnote 125

From the outset, Deakin agreed that the “condition of affairs which calls for legislation in Victoria is not, I am happy to say, in the remotest degree to be compared with the state of things that formerly existed in England”.Footnote 126 The Age also concurred with the view that child workers in Victoria were better treated than those in Britain, where “children were growing up without knowledge of this world or the next, with stunted frames and with the seeds that every disease and excessive work, foul air and unwholesome food can engender”.Footnote 127 However, in response to the conservatives’ arguments, the 1885 bill was presented by liberals as a preventative measure to ensure conditions did not get as bad as those in Britain: a “highly conservative country […] a much more conservative country than this”.Footnote 128 While “employers here aren't like those in England”, it was not “beyond the reach of possibility” that conditions should get as bad as they had been in England.Footnote 129 Instead, “our factory system will grow up under the lines of the law”, to prevent the abuses found in other countries by applying this act early.Footnote 130 For over a decade, liberals had relied on the following tenet: “[H]uman nature in the colony of Victoria is just the same as it is in England; that is to say, those who make their money out of their fellow creatures have no scruples whether their fellow creatures live or die if they can only make money”.Footnote 131

Liberals won the day in parliament, convincing members there was a child labour problem that warranted the regulation contained in the provisions of the 1885 bill. Unlike its predecessors, this bill was discovered to be extremely popular and was rapidly rushed through Parliament, though not without dissent.Footnote 132 The Factories and Shops (Vic) Act 1885 applied to factories and workrooms in which “six or more persons are engaged […] in preparing or manufacturing articles for trade or sale”, or where “steam or other mechanical power is used” (Section 3). The main provisions with regard to children were as follows: no person under the age of thirteen could be employed (Section 30); no person under the age of fifteen [13–14 years] could be employed unless they had been educated up to the standard required by the Education Act of 1872 (Section 30); and no person under the age of sixteen could be employed unless their employer had obtained a certificate of fitness for employment from a medical practitioner (Section 31).Footnote 133 All female factory workers and males under the age of sixteen were restricted to a forty-eight-hour week (Section 29). The Act also contained provisions regulating the employment of young people in night work and in the printing industry (Sections 34 and 35). Finally, children were protected by clauses related to safety, sanitation and environmental health.

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS

These are unexpected findings. Despite the perception by parliamentarians in Victoria – liberals and conservatives alike – that child factory labour was not as serious a problem as in Britain, the Victoria Act contained provisions related to age limits and hours that offered more protection to children than the British Act of 1878. In Britain, prohibition only applied to children under the age of ten, school attendance certificates were only required under the age of fourteen (or thirteen if granted a proficiency certificate) and, when regulations were met, permitted hours of work for factory workers were up to ten hours a day.Footnote 134

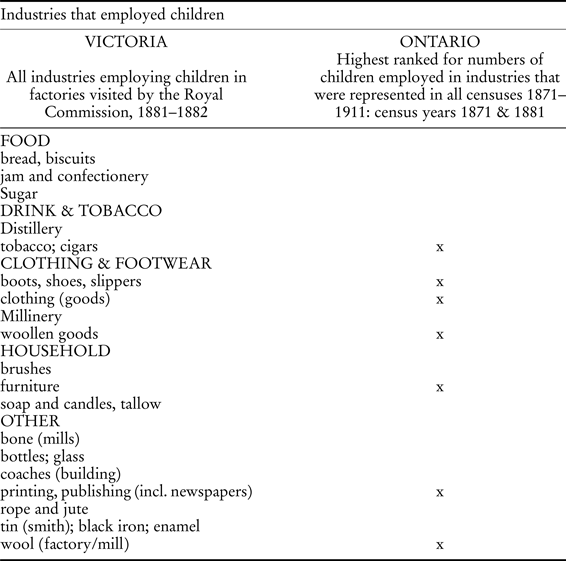

But how did the role and regulation of child labour in Victoria compare to other British colonies whose white settlers had also emigrated in search of a better life? Canada had much in common with Australia: a large landmass; dispersed population; and British parliamentary political processes. The majority of inhabitants were British immigrants or their descendants.Footnote 135 Many aspects of industrialization emanated from Britain in terms of machinery, skilled workers, and entrepreneurs.Footnote 136 The populations of urban centres doubled from 1871 – to reach over 1.5 million in 1891 – and manufacturing grew rapidly.Footnote 137 The province of Ontario, where eighty per cent of the population in 1871 was derived from British settlement, became the most industrialized of the provinces and shared major characteristics with Victoria.Footnote 138 Hurl presented census data showing industries in Ontario that employed the greatest numbers of children under sixteen years. Comparisons are difficult as the Commission in Victoria reported all industries in which child workers were observed. Nevertheless, there were important common industries. They include clothing (cotton and woollen goods), millinery, footwear, tobacco, printing, and furniture. The second column of the Appendix indicates those industries reported in Victoria in which a high number of child workers were employed in Canada.

A similar sequence of events also occurred in Canada related to the passage of child labour regulation. Federal parliamentary debates showed that reformers, led by Darby Bergin, recognized that the child labour problem was not as severe as in Britain but proposed more protective regulation as a preventative measure.Footnote 139 A series of federal factory bills (from 1879) failed to secure passage, leading to the establishment of a Royal Commission (1882), which subsequently reported the extensive employment of children working for low pay in harsh conditions.Footnote 140 It fell to the province of Ontario – which in 1871, under a liberal government, had enacted the nation's first law to provide free and compulsory education – to pass Canada's first factory act in 1884 (proclaimed in 1886).Footnote 141

Nevertheless, despite such similar characteristics, a comparison with the Ontario law also favours Victoria. Although the age regulations were much the same, with the limit in Ontario a year younger for boys (under twelve) and a year older for girls (under fourteen), at ten hours a day, permitted hours of work were higher in Ontario. There were also no educational requirements for those eligible for factory work.Footnote 142

A comparison can be made across all three jurisdictions. In each location, child labour was central to advancing industrialization: children worked as cheap substitutes for male adults in low skill jobs across a wide range of industries.Footnote 143 Reform was pursued in a common climate of British nineteenth-century morality. This present study identified fears about the corrupting influence of mixed workrooms and sanitation facilities. In Britain, children in factories were “regarded as being particularly vulnerable – physically or morally – and requiring special protection”.Footnote 144 In Canada, reformers also viewed child factory employment as “threatening to undermine the moral and physical foundations of the social order”.Footnote 145 Finally, the need for regulation was recognised by parliament in all three places. Nevertheless, the Victoria Act contained provisions related to ages and working hours that, in combination, offered the most protection to children. It also provided for the most effective enforcement. While a factory inspectorate was appointed in all three places, only in Victoria was it compelled to report to parliament. Only in Victoria were factories required to allow the entry of truancy officers. Although relative to Britain, the Ontario statute showed some aspirations in terms of age limits, Canadian historians judge that its lack of enforcement provisions rendered the legislation extremely weak. Victoria's top rank may be a result, at least in part, of differences in economic and political contexts.

In relation to the economy, Australia's superior wealth meant that relatively fewer children needed work than in Britain and Canada. From the 1870s until 1891, Australia's gross domestic product per capita was well above that of Britain and more than twice that of Canada.Footnote 146 Economic growth meant that trade unions in Victoria were influential in support of reform. While this present study showed that unions in Victoria aimed to reduce child labour largely to safeguard the interests of their male adult members, their goal of regulation coincided with that of reformers. Trade union recommendations strongly informed the Commission's report and subsequent legislation. In contrast, unions had little influence on reform in Britain and Canada. The British Trade Union Congress (TUC) – not established till 1868 – was not consulted by the Commission (that preceded the 1878 Act).Footnote 147 Further, it was not until 1883 that the Canadian Trades and Labour Congress was formed. It was not represented on the Commission (that preceded the Ontario Act of 1884) and was restricted to lobbying.Footnote 148

With regard to politics, the remoteness of Australia and the timing of the late British settlement in Victoria brought about interventionist tendencies that were adopted by colonial liberals in a mutually reinforcing programme of factory and education reform. Further, there was little of an established order to oppose aspirations for a better future. In contrast, the doctrine of laissez-faire “acted as a brake” on liberals in Britain.Footnote 149 Reform was espoused by conservatives. From 1833, they were led by Shaftesbury who was staunchly opposed to the idea of popular education, giving a “cold welcome” to the British Education Act of 1870.Footnote 150 Child labour reform was also proposed by conservatives in Canada. But, after the failure of their efforts to pass federal legislation, it fell to liberals in Ontario to champion reform. Laissez-faire among Canadian liberals, however, reached its peak in the 1870s.Footnote 151 Legislation, therefore, did not come about as the result of a clearly defined movement for social reform linking education and factory laws, but mainly for reasons of provincial political opportunism.Footnote 152

In tandem, the economic and political context of late-nineteenth-century Victoria helps explain why, of the three locations, reformers secured the passage of legislation with provisions that offered the most protection to children. In contrast to Britain and Canada, the wealth of the Australian colony provided an arena in which the ambitious aims of the colonial liberals could be initiated and enacted. They received the support of unions and did not face an entrenched opposition but, instead, opponents who were hamstrung by the achievements of Shaftesbury and their Tory counterparts in Britain. By repeatedly praising the British Act, conservatives lent support to the principle of reform.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study addressed the research questions posed at the outset. Was there a child factory labour problem in Victoria according to the norms of the colony as industrialization advanced? The success of the passage of the 1885 bill in Victoria showed that parliament acknowledged the existence of a child labour problem in factories and workrooms that was serious enough to require regulation. They were persuaded by reports from the Royal Commission, which described the employment of many children across many industries, and provided widespread evidence of low pay, long hours, harsh conditions of work, and ill effects of factory work on health and education. Was the Victorian child labour legislation of 1885 a “pale imitation” of the British factory act of 1878? This was not the case. Parliamentary debates showed that reformers explicitly aimed to build an improved society by securing the passage of more protective provisions to prevent the conditions that had arisen in Britain. Was the legislation passed through employers’ indifference or through the efforts of liberal reformers? Details of the bills alongside parliamentary and public debates showed that the legislation was passed by the efforts of liberal reformers in the face of over a decade of continuing opposition to reform from business interests. Truancy officers and the Commission were obstructed and deliberately deceived by employers. Nevertheless, liberals persuaded the majority of members of parliament to follow their lead. The findings of this study, therefore, do not support the conclusion of previous census-based studies of child labour in Australia.

The research also makes a contribution to academic debates about child factory workers in the Industrial Revolution. It offers strong support to explanations offered by Humphries in Britain, Goldin and Sokoloff in the US, and Hurl in Canada. Manufacturers established a division of labour whereby jobs were fragmented and some unskilled tasks were filled by children. Children were employed to price skilled adult males out of the market in industries across the board. They were paid a third of the adult wage and laid off when they became too expensive. Children were crowded in dangerous and unhealthy industries, jobs and sections of the production process where, in some instances, they were employed in greater proportions than adults. The mechanical processes imported from Britain, therefore, did not replace child workers. In contrast, these findings show that children were central to the Smithsonian-based organization of work. This study also identified poverty as a major cause of the child factory labour problem. The Commission concluded it was a fundamental explanation for why children worked in factories. Children lied about their ages, were reluctant to provide information to the Commission, and were observed queuing up for low-paid harsh work on a daily basis.

This research did not discern any factory employment of indigenous peoples (children or adults) in Victoria during industrialization. Yet, indigenous children were employed by white settlers in Australia well into the twentieth century.Footnote 153 A Queensland study found they were treated far worse than child workers from settler families: kidnapped, often receiving no wages, and suffering severe abuse from employers.Footnote 154 Moreover, the child labour provisions of laws that were passed for indigenous peoples in Western Australia (1896) and Queensland (1902) did not require employers to pay children for their work nor give them any education.Footnote 155 Robinson maintained that if laws similar to those for settler children had been enacted, they would not have been invoked as a result of racial attitudes among the settlers. Consequently, the relative lack of indigenous child labour legislation in Victoria would have made little difference, if any, to indigenous children who might have been working in factories.

The findings allow for a comparative assessment of the potential effects of the legislation on child workers themselves.Footnote 156 Children in Victoria had most to gain from the new regulations as fewer were permitted to work in factories and those eligible were prohibited from working long hours. Further, free compulsory state secondary schooling up to the age of fifteen years meant that the colonial liberal view of childhood as a time to be in school and “not an age for working full-time” might be fulfilled.Footnote 157 In contrast, Britain did not have free, compulsory education for children over ten until 1918; while in Ontario, it was only available up to the age of twelve.Footnote 158 However, this study has produced evidence that children in all three locations were sent to work because their family was poor and needed their wages. Paradoxically, the most stringent enforcement provisions in Victoria – had they been put into practice – might have prevented some of the poorest families from earning a subsistence livelihood through their children's labour, especially if work were not available for adults.

Limitations and strengths of the data warrant discussion. There was a reliance on Royal Commission data to identify child employment and work organization. Yet, the following procedures lent authority to the findings: the unannounced visits of the Commission; the location of interviews in the factories; the widespread sources of information; and reports of truancy officers and medical practitioners with years of experience. Such rich data, gathered from a broad range of industries, provide convincing contemporary accounts. Further, as much child factory labour was part of the informal economy – the compulsory provisions of the Education Act of 1872 meant that many children were likely working illegally – information missing from official sources was captured. In particular, these data also allowed the voices of children to be directly heard. Yet, as the reluctance of some child witnesses to provide more information probably reflected fears that parents would be fined, the likelihood is that the extent of child labour was under-reported to the Commission.

Finally, one of the major strengths of the data lay in the legal texts that allowed an analysis which produced a new finding. While the British Act of 1878 provided a broad framework, the actual child labour provisions of the Victoria Act of 1885 offered more protection to children, not just relative to Britain, but also to other industrializing colonies and countries. As this study has shown, reformers in Canada also searched for a better life, but the Victoria Act offered greater protection than the Ontario Act. Further, although there was earlier child factory legislation in parts of the US, Europe, and also in the nearby British white settler colony of New Zealand, comprehensive regulations that included provisions for effective enforcement were not passed elsewhere until the twentieth century.Footnote 159 The results of this research, therefore, contradict the accepted wisdom derived from secondary sources and repeated over a long period of time: from T.A. Coghlan – “the course of factory legislation in Australia was marked neither by originality nor intelligence; it was in fact the offspring of factory legislation in the United Kingdom” – to the current Australian Dictionary of National Biography, which states that the Victoria factory act of 1885 was “based largely on British legislation”.Footnote 160

In his oft-quoted maxim, Tawney maintained that “there is no touchstone, except the treatment of children, which reveals the true character of a social philosophy more clearly”.Footnote 161 The 1890s saw the onset of depression in Victoria, the weakening of child labour regulation, and the rise of a Labor party that became the later champion of factory reform. However, this study helps re-establish the character of late-nineteenth-century liberal reformers in relation to their attitudes to the role and regulation of child workers – albeit only of children of white settlers – in the most populous and industrialized region of a country that was described by the New York Times in 1891 as one of the “great and progressive English colonies”.Footnote 162

APPENDIX