When the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA; P.L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048) was enacted on November 16, 1990, it was a unique moment charged with hope; for the first time there was a tool to force the reluctant hand of museums, federal agencies, universities, and others to return Native American Ancestors and their belongings.Footnote 1 That hope was fleeting, however (Kanatas and Smith Reference Kanatas and Smith.2022; Lucas Reference Lucas2017; Yellow Bird Reference Yellow Bird2012). Several systemic problems were not addressed by the law, and the implementing regulation, 43 CFR Part 10, would not be published until 1995. Without guidance, what motivation was there to comply with the Act? For many museums and federal agencies, the two defined entities under the law, the emphasis was on “compliance,” despite Senator Daniel Inouye's passionate statement to Congress asserting that NAGPRA “is about human rights” (Dumont Reference Dumont2011:30). The perception remains among some museums and federal agencies that “compliance” is as simple as checking a box.

Further complicating the issue are the structural problems of space, stewardship, and funding still facing museums, repositories, federal agencies, and others with respect to collections (Bustard Reference Bustard and Skeates2022; Marquardt Reference Marquardt, Montet-White and Scholtz1982). Underlying these issues, however, is not only the most fundamental problem but also the most baffling one: many institutions do not know what is in their collections (Childs Reference Childs2004; Sullivan and Childs Reference Sullivan and Terry Childs2003; Teeter et al. Reference Teeter, Martinez and Lippert.2021). It has been more than 30 years since NAGPRA was enacted, but at least 110,000 Native American Ancestors have yet to be returned (Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, Hudetz, Ngu and Brewer2023; NAGPRA Review Committee 2022:21; Ngu and Suozzo Reference Ngu and Suozzo.2023). Boxes in the same curation rooms housing Ancestors also contain the remains of an unknown, uncounted number of persons of African descent. An initial estimate of “at least 2,000 African Americans—possibly many more” being housed in collections was offered by Dunnavant and colleagues (Reference Dunnavant, Justinvil and Colwell.2021): this estimate is acknowledged guesswork at best and, at worst, may be a mere fraction of the actual number of these individuals.

Compounding the horror of this situation are recent revelations about the forensic evaluation of and subsequent investigations into the identity of the remains believed to be those of Katricia Dotson (also known as Tree Africa), one of five children killed in the Philadelphia police bombing of the MOVE headquarters in 1985. In 2021 circulating reports asserted that the remains of Katricia, and possibly of Melissa Orr (Delisha Africa), were being held at the Penn Museum, studied without the knowledge or consent of their parents and used as teaching aids in university courses (Dickey Reference Dickey2022; Dunnavant et al. Reference Dunnavant, Justinvil and Colwell.2021; Heim et al. Reference Heim, Tulante, Graff, Tubbs, Ekhator and Hussain.2022; Miles Reference Miles2022; Pratt et al. Reference Pratt, Kastenberg and McKee Vassallo.2021; Tucker Law Group 2022). This underscores the reality that the acquisition of African American remains is not merely a result of past archaeological or anthropological collecting, which we so readily disregard as outdated practice; it is ongoing, and without question, unresolved.

In 2016, Justin Dunnavant presented a paper at the annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology calling for the creation of an African American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, AAGPRA, reviving a discussion that emerged following the 1991 rediscovery of New York City's African Burial Ground (Dunnavant Reference Dunnavant2016; McGowan and LaRoche Reference McGowan and LaRoche1996; Quintyn Reference Quintyn2023:7). In 2021, Dunnavant, along with Delande Justinvil and Chip Colwell, reaffirmed this need, decrying the pervasive dehumanizing treatment of African American individuals held in collections. In December 2022 Christina Miles proposed a modified ADGPRA—an “African-Descendant Graves Protection and Repatriation Act”—that broadened “the repatriation of goods” so it would “not be limited to descendants of enslaved Africans but rather be expanded to include all goods stolen from African or African American communities, at home and abroad.” Any legislation would require regulatory processes such as that of NAGPRA (43 CFR Part 10) to guide the disposition of African American individuals and belongings to their descendant communities. Those processes would likely include requirements for accountability and documentation of institutions’ collections, as NAGPRA did, but also like NAGPRA, may not make provisions for funding.

Although some institutions were able to meet their NAGPRA responsibilities,Footnote 2 many more were caught off-balance by its requirements and took years, even decades, to initiate work. Without meaningful changes to collections accountability, it is likely that these same institutions would be as poorly positioned to address any new legislation, such as a proposed AAGPRA. It is vital that institutions take the opportunity to rectify these deficiencies now, positioning themselves to meet their future responsibilities under potential new legislation and engaging frankly with descendant communities regarding their cultural heritage. It is now, and not in some undefined “future,” that institutions must develop plans for repatriation and ensure that they have a complete understanding of the collections under their stewardship.

In many cases, institutions—museums, federal agencies, repositories, universities, and others who may have NAGPRA or AAGPRA responsibilities—claim that insurmountable challenges prevent them from planning for repatriation. We mentioned an important one earlier—often, collections are not properly inventoried—but other barriers remain, including those of funding, staffing, and institutional support. In recognition of these challenges, we offer a model designed to encourage and promote progress over perfection, milestones over the finish line, and, above all, a self-reflective approach to initiating all repatriation activities. Although this model was inspired by conversations about the development of catalog inventories to facilitate the implementation of NAGPRA and AAGPRA, it is broadly applicable to collections work and the overall repatriation process.

THE START MODEL

First and foremost, we acknowledge the difficulty of taking the first step, and we recognize that in many institutions the individuals taking these steps may have no formal repatriation training. Whether in support of a federal law such as NAGPRA, prospective legislation such as AAGPRA, or other avenues of return (such as CalNAGPRA or international repatriation), “just starting” can feel daunting.

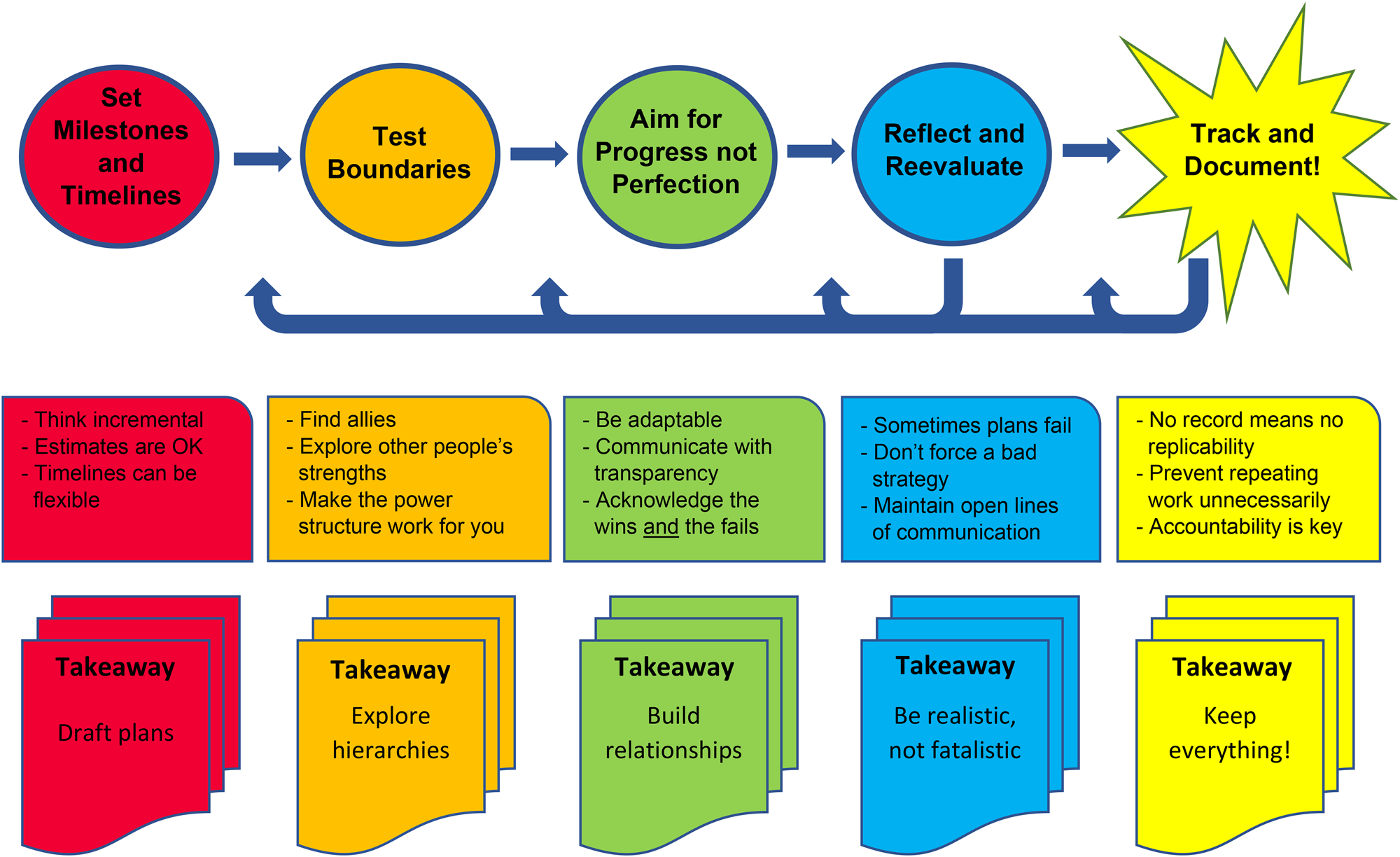

This model is organized into five steps, each of which is focused on helping you make progress incrementally but steadily, using resources you already have (Figure 1). For each step we summarize its importance and relevance to NAGPRA, AAGPRA, and collections work generally; provide some suggestions for specific tasks to target based on the lessons from NAGPRA (the “whats”); and discuss possible methods of accomplishing those tasks in support of a future AAGPRA (the “hows”). In summarizing what we considered to be the crucial phases of this model, we leaned heavily on the expertise and existing work of many scholars, incorporating their experiences and suggestions into an approach that we hope will empower others on their repatriation journeys (for further reading, see Bauer-Clapp and Kirakosian Reference Bauer-Clapp and Kirakosian2017; Benden and Taft Reference Benden and Taft.2019; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Martindale, Supernant and Elvidge2023; MacFarland and Vokes Reference MacFarland and Vokes2016; Meister Reference Meister2019; Miller Wolf Reference Miller Wolf2019; Teeter et al. Reference Teeter, Martinez and Lippert.2021; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Thompson, Garland, Butler, deBeaubien, Panther and Hunt2023).

FIGURE 1. The START model.

Set Milestones and Timelines

Milestones and timelines comprise the bulk of the 43 CFR Part 10 regulation. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that preparing for implementing those regulations requires diligence and accountability. A good plan can lead to institutional support and successful collaborations, and it can help foster relationships, even if some of your milestones are a long way from being reached. It seems likely that an AAGPRA implementing regulation would model itself on the NAGPRA regulations, at least as far as milestones and timelines are concerned.

What: Specific Tasks

(1) List, develop, and draft plans. We suggest an inventory plan, a communication plan, a collections care plan, and a repatriation plan as a starting point. A strategic plan to present to your leadership or management might also be helpful for long-term visioning (Table 1). One of the greatest impediments presented by NAGPRA is that it is an unfunded mandate; AAGPRA may be the same. Think through these challenges and identify potential solutions.

(2) Develop internal policies and procedures now. Lessons from NAGPRA suggest that timelines may be in the range of six months to two years. Some suggested policies include ones on repatriation, access and use, consultation, a treatment of human remains, and on traditional care (Table 1). We suggest that you determine any additional “as needed” policies in consultation with descendant communities.

TABLE 1. Selected Communities of Practice.

Note: Communities represented herein are intended as a starting point only and do not represent a comprehensive or complete list. AAA = American Anthropological Association; SAA = Society for American Archaeology. Websites accessed October 14, 2023.

How: Methods

(1) Use existing resources provided by professional organizations and colleagues to draft your documents (Table 1). Although there are not yet dedicated resources specific to AAGPRA, it is logical to assume that preparatory steps undergone for NAGPRA will also provide a foundation for AAGPRA.

(2) Use existing records; you may already have incomplete catalog records or provenance information that you were not aware of, especially if your records have not been digitized. It never hurts to check with the experts, such as registrars, archivists, librarians, curators, collections managers, and records managers.

(3) Make use of communities of practice that are facing the same challenges you are and finding innovative solutions collaboratively (Table 1). Join those communities and benefit from their knowledge or start one yourself at your institution and begin to build your support network.

Test Boundaries

Depending on your role at your institution, you may be authorized to initiate some, all, or possibly even none of what we recommend in this article. An important step in the START model is to recognize and address your personal and professional limitations, so that you can push the boundaries and gain ground on working toward your goal. If you become familiar with the roles and responsibilities of the people around you—in your department or other organizational structures—you can envision how to negotiate the limits of your and their positions to achieve some or all of your milestones. Be aware that testing boundaries may pose a degree of professional risk.

What: Specific Tasks

(1) Identify allies, obstructors, and supporters. Know who will collaborate with you, who can help you push forward your initiatives, and who might present challenges and, more importantly, why. Uncooperative institutional administrations delayed NAGPRA for decades. Understanding where challenges might arise for new repatriation efforts at your institution will help you address them early and effectively.

(2) Recognize that your greatest allies are the descendant communities whose relatives are in your collections spaces and avoid excluding or disregarding them throughout the process (Table 1).

(3) Get your leadership or administration on your side. Underscoring the importance of preparing for AAGPRA can help generate various forms of support, including financial support to complete inventories or hire personnel, students, and the like. Funding is the first and most persistent barrier faced by institutions seeking to complete NAGPRA work, and we should expect that to be the same for AAGPRA.

(4) Take initiative. Are there smaller steps you can take now, such as engaging a volunteer to help go through boxes? Are there resources (grants, for those not employed by federal agencies, communities of practice, trainings) that you can leverage to gain the attention of your institution? Can you engage with the descendant communities in your area or those who are connected to the individuals in your institution's collections?

(5) Explore setting up advisory boards comprising descendant community members to help guide you.

How: Methods

(1) Look at your institution's departmental or leadership structure. Reach out and build your network until you have a comprehensive knowledge of the position of each person in your institution as it pertains to your goals.

(2) Develop a brief or presentation that includes an overview of the importance of repatriation and what it entails, such as a collections inventory that includes an identification of African American or Native American Ancestors and belongings, as well as your milestones and budget. Include what support you will need and from whom; this support can include both financial and staffing support, as well as resources such as software, hardware, or equipment. If any descendant communities have previously expressed interest in the collections, include that information as well.

Aim for Progress, Not Perfection

It is natural to want the methodology to be perfect before we start. Although some people may thrive through an organic process, success is generally tied to planning. Yet, when planning becomes single-minded pursuit of perfection, you have entered a harmful holding pattern. The START model asks you to let go of perfection and instead focus on taking small steps that keep you moving forward. Progress can be as simple as cataloging one box at a time.

What: Specific Tasks

(1) Research the archaeologists (or donors) who created the collections and the context in which they were generated. Projects are tied to place and are funded through various means (private, federal, state). State and federal laws may have been applicable, and permits may have been generated to undertake the archaeological work. These will affect stewardship responsibilities, consultation requirements, and curatorial stipulations.

(2) Familiarize yourself as soon as possible with the descendent communities who may have connections to the people or objects within your stewardship. Be aware that these communities may be diasporic, extending beyond the local or regional boundaries from which the individuals or objects were excavated or the repository is located (Table 1).

(3) Establish relationships with descendant communities as soon as possible and engage in meaningful discussions about (1) how you can care for the individuals and objects within your stewardship and (2) how you can support their relatives or communities in doing the same. Descendant communities may have specific religious, sacred, or traditional care requests for the treatment of their Ancestors and cultural heritage.

(4) Start developing catalog inventories. Without catalogs, even incomplete ones, it is harder for institutions to conduct meaningful consultation and for descendant communities to identify cultural items. An accountable catalog should have as much information as possible, including about provenience information, the contents of the collection, repository tracking information (like box numbers or catalog numbers), and cultural associations or time periods of the site if those are known.

How: Methods

(1) Research and gather site records, permit applications, and project reports. Federal and state agencies should have records for projects undertaken or permitted by them. State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs), Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs), historical societies, and other community organizations may also have supplemental records (Table 2). Records of consultation with descendant and interested communities, if relevant, should be found in your institution's records.

(2) Familiarize yourself with regulations, best practices, and other standards pertaining to collections management, such as 36 CFR Part 79, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act.

(3) Publish public notices in local and regional newspapers to invite descendant communities to meet with your institution.

(4) Draft letters to communities that are already known to you; letters may be sent to spiritual or community leaders, families, and anyone identified as having a known or possible relationship to the individuals and cultural heritage in your care.

(5) Federal and state agencies, as well as historical societies, may have documentation or other archival resources that could be useful in identifying communities to contact.

(6) Develop working groups among similar institutions to facilitate communication and efficacy. Invite descendant communities to your institution to visit with you or a repatriation committee, to care for their relatives, or to help you identify objects.

(7) Enlist volunteers, students, or interns or get permission to hire part- or full-time support staff to open every box.

(8) If your institution does not have collections-management database software, consider investing in a program. It will help maintain accountability and make it much easier to produce inventories and summaries for AAGPRA or NAGPRA when needed.

TABLE 2. Additional Planning Resources to Aid Practitioners.

Note: Resources are examples only and are not intended as a comprehensive, endorsed, or complete list. AAIA = Association on American Indian Affairs; AAM = American Alliance of Museums; ICOM = International Council of Museums. Websites accessed October 14, 2023.

Reflect and Reevaluate

To be dynamic, you must be flexible and self-reflective. Often this means that you will need to reevaluate your priorities, goals, and milestones. Furthermore, being honest with yourself and your institution, including and especially your management/leadership, can push you to identify new strategies for overcoming problems. Take the time at each milestone to reflect, and if you need to take a step back to reevaluate, do not let it demoralize you. Instead, be open to inspiration.

What: Specific Tasks

(1) Set up regular meetings to touch base with your team and your institution to provide progress reports and to identify challenges before they become impediments. Be ready and willing to change course when necessary.

(2) Have an outside party review your plan for feasibility. Sometimes we cannot be objective about our own work or recognize when our own goals are unrealistic. An outside perspective can hold us accountable and keep us grounded.

(3) Build reflection points into your milestones. Commit to evaluating the level of success of each completed milestone and documenting how it could be improved if repeated.

How: Methods

(1) Early in the process, identify someone who is able and willing to provide review and feedback for you. This person (or persons) should be technically competent so that they can understand the scope of the project without explanation, but they should not be personally involved. An outside party can be more objective.

(2) Ensure that your progress meetings include everyone who should be kept informed, as well as every member of your team who will have progress to report, if relevant.

Track and Document

This step should be designed to answer one question: If you left your job tomorrow, could someone else continue your work? If the answer is “no,” then this is the time to reevaluate how you maintain your administrative records. Documentation is a critical aspect of NAGPRA, and it will be just as important for AAGPRA. Keeping an accessible, organized, and meticulous administrative record protects you, your institution, and the descendant communities with whom you collaborate.

What: Methods

(1) Keep everything: all your notes, correspondence, sketches, and plans. The administrative record is a critical component of success; the easiest way to waste the resources you have is to redo work that was already done.

(2) Organize logically. Your administrative record is useless if it cannot be accessed or understood. Federal agencies and museums struggle with piecing together early (and sometimes even recent) NAGPRA repatriations because the records were lost, never produced, or simply cannot be sorted through. Preparation now will prevent the same problems for AAGPRA work.

How: Methods

(1) Use a duplicate system of paper and digital files, when possible. Ensure that any document you create on paper is also saved to a central network or drive or to a stable external source. Have naming conventions that make sense for you and make your progress easy to retrace and create a key to those conventions for outside users.

(2) Keep a separate file that tracks your milestones and progress toward them. Ensure that this is always kept up to date.

(3) Maintain accurate records of all communications with descendant communities, both in a log including dates and communities corresponded or consulted with, as well as digitized copies of meeting minutes, emails, and letters. Copies of meeting minutes should always be provided to all meeting participants.

CONCLUSION

The conversation concerning AAGPRA legislation is ongoing but still unresolved. Dunnavant and colleagues’ (Reference Dunnavant, Justinvil and Colwell.2021:338) observation that “there are still no federal protections specifically for historic Black cemeteries” has been addressed partly by the recent African American Burial Grounds Preservation Program, which provides long overdue protection for burial grounds and cemeteries; it was included within the Consolidated Appropriations Act (at Section 643), signed on December 29, 2022 (Brown 2023; Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023). However, lawmakers must still seize the opportunity to advance supplemental legislation to address or provide for African American persons already held in collections across the nation, and institutions must hold themselves accountable to prepare for that legislation. The fact that Native American Ancestors are still being “discovered” in boxes, labs, or curation spaces after more than 30 years of NAGPRA is demoralizing (Hodison Reference Hodison2022; Mize Reference Mize2023). That individuals of African descent are largely invisible in collections entirely is staggering. By not properly—and compassionately—managing collections from the start, we have undermined our own ability to be accountable.

We are once again at a pivotal point as the discipline awaits legislation supporting expanded repatriation. It seems likely at this point that there will be an AAGPRA in some form, and institutions must prepare themselves to return the Ancestors of descendant communities in the expeditious fashion that many failed to achieve after the enactment of NAGPRA. The benefits of developing plans to achieve this success include the streamlining of existing efforts to complete repatriations under NAGPRA and accountability in the stewardship of remaining collections. We offer the START model as a tool to help practitioners organize and orient themselves to meet the common goal of respectful return by taking small and achievable steps. The key takeaway from the START model is simple: empowerment is a choice. There is always the potential to make meaningful progress, even if it is incremental.

Acknowledgments

No permits were required for this work.

Funding

No funding was provided for the work presented in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No original data are published in this article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.