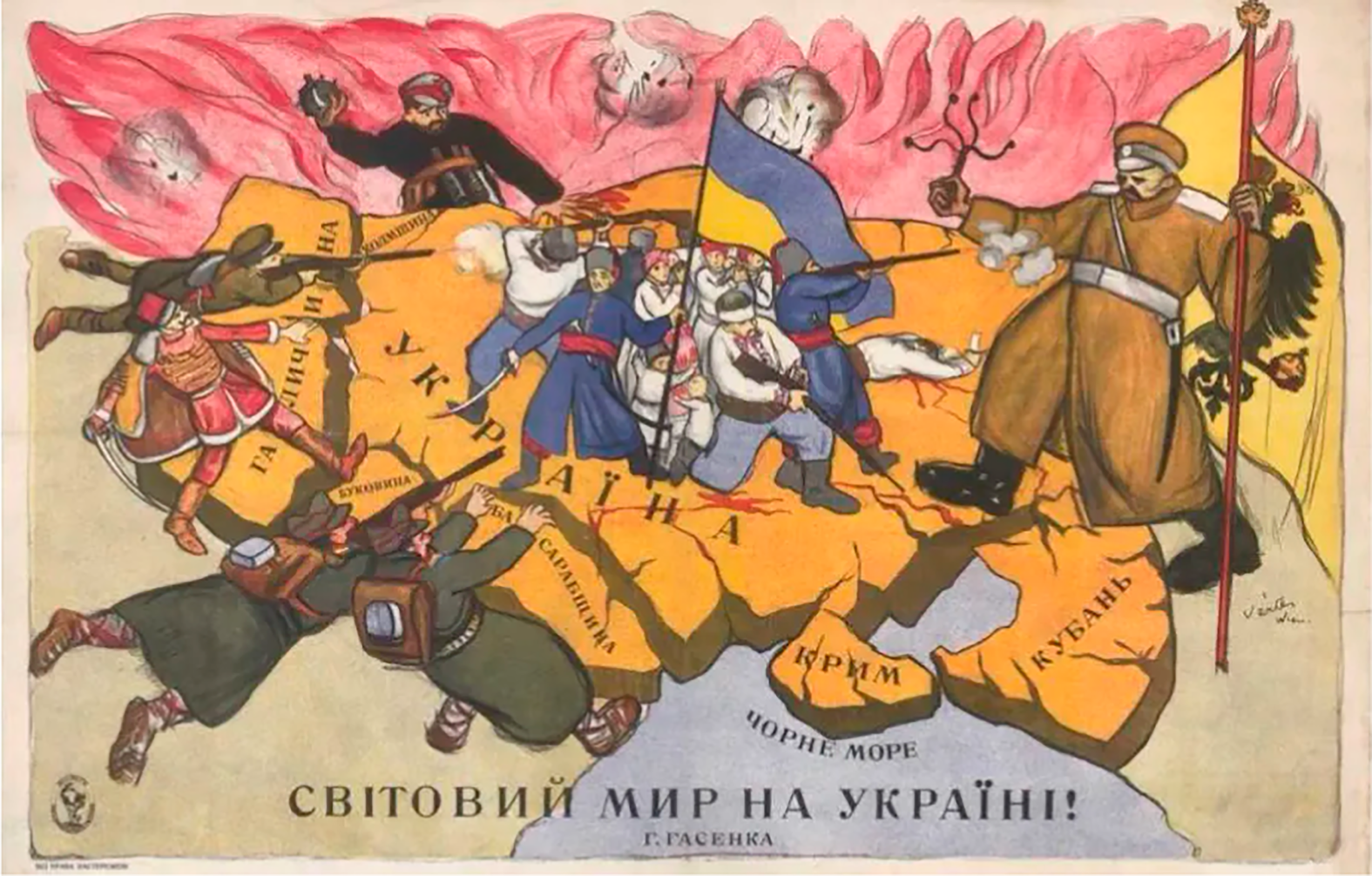

This poster, published in 1919 with the title “World Peace in Ukraine,” reflects skepticism about trying to settle territorial disputes through the Paris Peace Conference.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine, initiated on February 24, 2022, is among the most—if not the most—significant shocks to the global order since World War II. Its impact is of course most directly felt by Ukrainians, who have suffered enormous devastation and are still, as of this writing, fighting for their national independence. However, the stakes of Russia's invasion extend well beyond the horror that has unfolded in Ukraine. They go to the very heart of contemporary international law and to the world order that it has helped to create. International lawyers should be clear about the seriousness of this threat to the prohibition on the use of force, to the territorial integrity of states, and to the basic right of peoples to determine their own political fates. Only by recognizing these stakes can governments and other international actors meaningfully assess their problems and possibilities, and plan for what is to come.

I. The Challenge

By invading Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has made plain that he now rejects the foundational principle of the post-World War II order—namely, that international boundaries may not be changed with force alone. Putin foreshadowed his willingness to upend the global order in 2007, during a speech at the Munich Conference on Security Policy. There, he announced that he was “convinced that we have reached that decisive moment when we must seriously think about the architecture of global security.”Footnote 1 He directed his criticism at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), especially the United States, which, in his words, “has overstepped its national borders in every way” and tried to create a “unipolar world” with “one centre of authority, one centre of force, one centre of decision-making.”Footnote 2 In this world order, he said, “no one feels safe.”Footnote 3

Putin publicly challenged this order in the summer of 2021, when he escalated his rhetoric on Ukraine. He wrote an essay highlighting Russia's shared history with Ukraine and blaming the West for instituting in Ukraine a “forced change of identity.”Footnote 4 He characterized Ukraine as part of an “anti-Russia project” “under the protection and control of the Western powers.”Footnote 5 His essay was full of conspiracy theories and lies, but the message was clear: “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia.”Footnote 6 Russia would no longer tolerate a truly independent Ukraine, free to distance itself from Russia and align more closely with the West.

Putin repeated these themes in a national address days before invading Ukraine. Ukraine, he said, “is not just a neighbouring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space.”Footnote 7 Since “time immemorial” the people “living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians.”Footnote 8 The speech denies that Ukraine can ever be a legitimate state in its own right. According to Putin, “the Ukrainian authorities” built “their statehood on the negation of everything that united us, trying to distort the mentality and historical memory of millions of people, of entire generations living in Ukraine.” Ukraine, Putin went on, “never had stable traditions of real statehood.”Footnote 9

At the same time that Russia was denying Ukraine's statehood, it was amassing its military forces at the border with Ukraine. “You have a choice,” Russia effectively told the world: “accept that Ukraine is ours, functionally if not also formally, or suffer the consequences, which we assure you will be severe.” In December 2021, Russia demanded that NATO and the United States not expand further eastward, including into Ukraine, and not engage in any military activities in the former Soviet republics.Footnote 10 These demands were rejected for the same reasons that they were made.Footnote 11 They were not only, and even primarily, about the future of Ukraine. They were also about principles at the heart of the post-World War II international legal order: each country is entitled to territorial integrity and to the basic conditions for its own self-determination. To state the point in the negative and in the most minimal possible terms: countries may no longer acquire foreign territory through the use of force.

II. The Stakes

It is easy to blame NATO, and especially the United States, for their hypocrisy about the use of military force. The United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries have routinely pushed the boundaries on or violated the UN Charter prohibitions on the use of force and in other ways interfered with the political independence of other states. In announcing the invasion of Ukraine, Putin himself referred to the U.S.-led operations in Kosovo, Iraq in 2003, Libya, and Syria—the legality of each of which was seriously in doubt. We do not intend in this Comment to defend U.S. military or foreign policy. We both are highly critical of it.

And yet, we think it is important to emphasize that the invasion of Ukraine is unlike the others, for two reasons. First, this invasion is a clear repudiation of the norm at the core of the UN Charter system on the use of force: the prohibition of forcible annexations of foreign territory. Second and in part for that reason, it does not have, baked within it, a limiting condition to explain why the use of force might be justifiable here but not in other locations where people continue to harbor historical grievances about the internationally recognized borders that they have inherited. Although Putin made some half-hearted arguments about genocide and self-defense,Footnote 12 the only plausible explanation for this invasion, given the facts—and, again, this is the explanation that Russia itself has most stridently advanced—is that it simply rejects the idea of an independent Ukraine. This explanation hits at the holy grail of the post-World War II order.

Because the Iraq 2003 war might be the closest analogue to Russia's invasion, it is worth explaining why even that operation—which also violated the UN Charter, caused enormous devastation, and was an egregious abuse of national power—was different in kind. As an initial matter, Iraq itself had tried to annex Kuwait in August 1990. In the intervening period, the UN Security Council had imposed on Iraq harsh weapons disarmament and remediation obligations,Footnote 13 and had passed multiple resolutions condemning Iraq for its violations of international law and efforts to evade UN weapons inspectors.Footnote 14 Just a few months before the U.S.-led coalition initiated the 2003 invasion, the Security Council adopted Resolution 1441 “[r]ecognizing the threat Iraq's non-compliance with Council resolutions . . . poses to international peace and security,” “[d]eploring the fact that Iraq has not provided an accurate, full, final, and complete disclosure” of its relevant weapons programs and “with regard to terrorism,” and “[d]ecid[ing] that Iraq has been and remains in material breach of its obligations.”Footnote 15 In our view, the Security Council should not have adopted that resolution. But the fact is that it did, and once it did, it altered the legal and political landscape for what would follow. Resolution 1441, and all the baggage that pre-dated it, gave the United States the room to offer a justification for invading Iraq that, for all its defects, did not easily extend to other cases.Footnote 16 The U.S. legal position had a limiting principle built into it.

Western countries have offered different limiting principles for other actions that they have taken that have pushed the boundaries on or violated the UN Charter.Footnote 17 In other words, they have provided explanations for why their uses of force were in their view acceptable in those cases, even if not in other cases that would not replicate the same mix of factual, legal, and political considerations. For example, the NATO bombing of Kosovo was defended in part as necessary to avert an ongoing humanitarian crisis, in the face of the Security Council's persistent inaction.Footnote 18 President Trump's airstrikes in Syria were said to be about that country's repeated use of chemical weapons, in violation of fundamental international legal norms.Footnote 19 These efforts to justify specific operations in terms that are constrained are important, even if they are unpersuasive in law, even if they have contributed to divisions between the West and other countries, and even if they open the spigot for additional uses of military force going forward.Footnote 20 (Any precedent is, after all, a precedent.) The reason they are important is that they communicate a sustained commitment to—indeed, they are limited so as to preserve—the core norm against forcible annexations of foreign territory. They are a way of saying, “that is the norm that we will not touch.” That one is the holy grail. It is what, for all the other problems in this world, we must insist on if we are to avoid regressing to the colonial projects of the past, which involved levels of brutality and oppression on such an extraordinary scale that it is nearly impossible to fathom.

By contrast, Russia's invasion of Ukraine is—and is meant to be—an attack on that core norm. This invasion is a war of territorial conquest, specifically designed to annex another country by force, for no reason other than that Russia has decided that it should no longer exist as an independent state. Unlike Iraq in 2003, Ukraine in 2022 had not been sanctioned for trying to annex another country for nationalistic gain. There is no reason to believe that it had secretly tried to develop weapons of mass destruction. It had not repeatedly been found to be in violation of UN Security Council resolutions or other fundamental norms of international law. It had not committed mass atrocities or used chemical weapons against its own people, and there was no looming humanitarian crisis to avert. Ukraine was simply trying to define a future for itself, at some remove from Russia. And that is the main reason that Russia has given for invading it. Russia's invasion of Ukraine puts the prohibition on forcible annexations, which was already showing signs of weakening,Footnote 21 openly up for grabs.

As such, this invasion is not just another in a long string of violations of Article 2(4). It threatens the stability of borders around the world, borders that are often arbitrary and even unjust, but on which the current world order is premised. And though the problems with this order run wide and deep,Footnote 22 the stakes of tearing up its basic foundations, in the way that Russia has chosen to do, are extraordinarily high. Many countries are already suffering from food and energy shortages and high levels of inflation as a result of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. As of this writing, we still do not know whether it will lead to a broader regional or world war, or the use of nuclear weapons, in this case. Any such action would have ramifications for the entire planet, even if it would be most acutely felt by those who are directly involved.

Moreover, whatever happens in this case, the lack of a credible limiting principle coupled with Russia's territorial ambitions has far-reaching implications for other cases. This is true, even assuming, as Anastasiya Kotova and Ntina Tzouvala argue in their contribution to the agora in this issue of the Journal, that credibility is the currency of the powerful.Footnote 23 The Kenyan ambassador to the UN eloquently made this point before the UN General Assembly: “across the border of every single African country live our countrymen with whom we share deep historical, cultural, and linguistic bonds.” With statehood, he said, African countries:

agreed that we would settle for the borders that we inherited. But we would still pursue continental political, economic, and legal integration. Rather than form nations that looked ever backwards into history with a dangerous nostalgia, we chose to look forward to a greatness none of our many nations and peoples had ever known. We chose to follow the rules of the OAU [Organisation of African Unity] and the United Nations Charter not because our borders satisfied us but because we wanted something greater forged in peace.Footnote 24

That basic compromise lies at the heart of the UN Charter, which promises both territorial integrity and self-determination, two principles that are often in tension with one another but have nevertheless persevered together.Footnote 25

Once that compromise is reopened, who else might decide that they want to acquire territory by force? Even before the invasion of Ukraine, historians and international relations scholars warned that economic and geopolitical changes were making a global war increasingly likely.Footnote 26 Extensive historical research by political scientists suggests that disputes over territory are more likely than other kinds of disputes to result in war. As one of us noted back in 2017, Ukraine fit that profile perfectly.Footnote 27 But of course, it is not the only region in the world that does. International law secures territorial borders and quells territorial conflicts through a variety of norms, including not only the prohibition of territorial conquest and the protection of territorial integrity through Article 2(4) but also the lack of a right to violent secession and uti possedetis, as the above quote from the Kenyan ambassador suggests.Footnote 28 Because the precedent set by the Russian invasion offers an opening to the many other state and non-state actors who are displeased with their inherited borders, it might be especially dangerous in unleashing additional violent conflicts.Footnote 29

III. The Response

The question is to what extent other moves to acquire territory by force can effectively be deterred. In the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, NATO states have solidified their security commitments to one another and, in June, invited Finland and Sweden to join their ranks.Footnote 30 The United States has also reinforced, with both words and deeds, its security alliances with other countries, especially in Asia.Footnote 31 These efforts are, perhaps, welcome stopgaps in the short term, but they are not, in our view, sustainable or sufficient over the long term. They are too dependent on the hyperpower of the United States, which is already stretched thin, in decline (in both its material and its normative manifestations), and being exercised in ways that are disconnected from U.S. national politics and problems. In these conditions, U.S. partners should not be confident that the United States will be able to do what it takes to protect them from attack, at least not without massive support from many other states. Thus, the future, in our view, depends much more on what these other states do—on whether they are sufficiently invested in the core principle that has for decades defined the world order and are willing to do what is necessary to fight for the cause, even when their own country is not in the direct line of fire.

The global response to the invasion of Ukraine has shown some promise. In the July 2022 Contemporary Practice of the United States section of AJIL, Kristen Eichensehr reviews the extensive practice of states, international courts, and other international institutions in condemning Russia's conduct in Ukraine.Footnote 32 In the UN Security Council, most states denounced Russia's invasion as a blatant violation of the UN Charter.Footnote 33 The Security Council also considered a draft resolution, submitted by eighty-two countries, that would have condemned Russia's aggression and called for an immediate ceasefire in Ukraine.Footnote 34 That resolution failed on account of Russia's veto.Footnote 35 The Security Council then called for an emergency special session of the General Assembly, which met from February 28 to March 2 to discuss the situation in Ukraine.Footnote 36 At the end, the General Assembly adopted a resolution that, among other things, “[d]eplores in the strongest terms the aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine in violation of Article 2(4) of the Charter.”Footnote 37 States have also widely denounced the invasion in other venues, including the G7,Footnote 38 NATO,Footnote 39 and the Organization of American States.Footnote 40

Within days of the invasion, Ukraine initiated proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming that Russia misapplied the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.Footnote 41 On March 16, the ICJ issued an order determining that “it is doubtful that the [Genocide] Convention . . . authorizes a Contracting Party's unilateral use of force in the territory of another State for the purpose of preventing or punishing an alleged genocide,” and directing Russia to “immediately suspend the military operations that it commenced on 24 February 2022 in the territory of Ukraine.”Footnote 42 The European Court of Human Rights separately also ordered interim measures in a case that Ukraine filed before it, directing Russia “to refrain from military attacks against civilian and civilian objects . . . within the territory under attack or siege by Russian troops.”Footnote 43

These moves against Russia are important, but there are troubling signs just beneath their surface. From the outset, states that are not closely allied with the United States have been less active in condemning and sanctioning Russia, creating a dynamic in which this war is mostly waged with massive support for Ukraine by the West and its closest allies, and many other states standing on the sidelines. For example, India and the United Arab Emirates both abstained from the Security Council vote on the resolution condemning Ukraine.Footnote 44 In the General Assembly, five states voted against the resolution, and thirty-five abstained; these states were overwhelmingly Asian and African states.Footnote 45 And while China has historically championed traditional notions of sovereignty and non-intervention, it has failed even to condemn the Russian invasion and seems instead to support Russia in blaming the West.Footnote 46

To be clear, the problem with this dynamic is not that some countries question or resist U.S. and Western leadership. The problem is that the international order has depended, at the most basic level, on the prohibition on the use of force for territorial acquisition. For this prohibition to stay salient, other states must invest in it and not let it slip away. However reasonable the decision to stay on the sidelines might be on a state-by-state basis, it comes at a cost to the basic, so-called “community interests” that are now at stake.

IV. Implications

Russia's invasion of Ukraine will also have other—perhaps less obvious and more indirect—effects on an array of international legal norms, as the agora Essays in this issue of the Journal begin to explore.Footnote 47 Some of these developments might be positive, others not, and we do not offer an opinion on them here. But international lawyers and policymakers should bear in mind the long-term and multivariant effects of the invasion, as they consider how best to mitigate the harms and plan for future eventualities. For example, sanctioning and condemning Russia's conduct helps to reinforce the norm against forcible annexations. But some of the moves in this direction might further entrench divisions between Western and non-Western countries both in the specific context of Ukraine and on other global issues; they might be dismissed as mere posturing for national gain, if not done with broad support; or they might change well-settled legal rules that facilitate desirable activity in other areas, ranging from trade and commerce to the enforcement of judgments and beyond.

Several Essays in the agora explore the unprecedented actions that states have taken against Russia. Some of these actions, such as the freezing of Russian state-owned assets and the banning of Russian ships from national port, are framed as sanctions.Footnote 48 Agora authors argue that, in both of these contexts, third-party countries have responded to the war by taking or considering measures that have historically been used only by warring parties themselves. Himanil Raina argues that the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have all banned “Russian” ships based not just on the registration of the vessel but also on the nationality of the owners or the chartering parties.Footnote 49 Although “piercing the veil of a ship's registration” has been a common practice in war to target “enemy” vessels, he explains, the practice in peacetime has been to assign nationality on the basis of registration alone. Similarly, the United States, Canada, and the EU have considered confiscating frozen Russian state-owned assets (including central bank assets) and using them for reparations or to aid Ukraine.Footnote 50 Anton Moiseienko argues that these measures, which raise issues of international economic law and immunities, might have a historical basis in the old rules governing how warring parties treated enemy property.Footnote 51 In effect, these two Essays argue, the line between peace and war has blurred during this conflict,Footnote 52 with potential implications for non-wartime activity in the future.

Beyond formal sanctions, many countries—especially in Europe—seek to limit their dependence on Russian energy through strategies, such as nationalization and diversification, that might violate international legal rules on trade and investment, a trend that Anatole Boute examines in his Essay.Footnote 53 The conflict has even seeped into private international law. Jie (Jeanne) Huang explains that Ukraine has declared under the Hague Service Convention that service requests made or issued by Russian authorities in occupied areas are null and void and have no legal effect. Poland, Lithuania, Finland, Estonia, Germany, and Latvia have likewise declared that they will not accept any documents or requests from Russia that result from its occupation of Crimea.Footnote 54 Russia has issued a counter-declaration. These declarations create uncertainty for foreign litigants who seek to serve defendants in Ukraine and thus about the recognition and enforcement of the resulting judgments. Considered holistically, the strategies that individual countries have used to condemn or counter Russia all lean in the direction of expanding the space for unfriendly unilateral actions by limiting or shaping the legal regimes that govern different areas of international law, including shipping, trade, immunities, investment, and private law instruments.Footnote 55

The invasion has also emboldened international and regional organizations. Martina Buscemi argues that a range of global international organizations have suspended Russia or otherwise limited its participation in meetings or decision making, even when the legal basis for doing so is unclear.Footnote 56 In her view, the “paralysis” of the UN Security Council during the war has helped to produce more powerful international organizations.Footnote 57 Buscemi's assessment is consistent with what Elena Chacko and Katarina Linos find with respect to the EU, which has centralized its authority over foreign policy, energy, and migration during this war.Footnote 58 These moves were partly a response to practical problems, such as the massive influx of Ukrainians fleeing the war,Footnote 59 but they also reflect efforts to isolate and punish Russia.Footnote 60 In this context, too, the invasion may have a lasting impact—here, in the form of international or regional organizations that have adapted to be more nimble and potentially more powerful but also less inclusive, at least in relation to Russia.

Other developments described in the agora could also contribute to a more fragmented global order. Laura Dickinson and David Sloss anticipate this possibility. They argue that “a worldwide coalition of liberal democracies and hybrid states” is developing and that “IHL is a domain where the seeds of [this] new liberal plurilateral order are taking root.”Footnote 61 Nikola Hajdin focuses on international criminal law, arguing that prosecutions for the crime of aggression need not be limited to Russian government officials and could extend to private individuals.Footnote 62 It is not clear, however, whether expanding liability for the crime of aggression would feed or disrupt the kind of plurilateral order that Dickinson and Sloss envision. Enforcement of international criminal law is sometimes seen as a tool available to powerful countries at the expense of the weak.Footnote 63 Hajdin's broad reading of the conduct covered by international criminal law thus might exacerbate the fissures between the Global South and the West in this area, even if it also in certain ways bolsters the prohibition of aggression.Footnote 64

There might be opportunities to bridge the distance between the West and other countries, especially in the Global South. Henning Lahmann argues that technological advances, such as open-source investigations, have the potential to unify states by providing a shared factual base from sources other than governments. The open-source investigations did not appear to have this effect in the UN deliberations on Russia; in other words, the “amount and quality of incriminating evidence” did not appear to motivate more states from the Global South to condemn the aggression.Footnote 65 And as described above, initial signals point toward more divisions among groups of countries, rather than less. But of course, these technological advances might be used differently in other settings.

Finally, the events in Ukraine underscore the racial and other inequalities upon which international law is built—and that it in various ways continues to perpetuate.Footnote 66 Marissa Jackson Sow describes how countries use refugee law, both in response to the events in Ukraine and beyond, not for the universal benefit of refugees but to secure their own whiteness and reinforce hegemonic political ordering. Anastasiya Kotova and Ntina Tzouvala note that legal defenses that Russia has given for the invasion mirror those that the West has given for the use of force in Iraq, Kosovo, and beyond.Footnote 67 They argue that “jus ad bellum debates would benefit from extending to all imperial powers the same level of scrutiny and disbelief” that the West has exercised vis-à-vis Russia's justification for the invasion.Footnote 68

V. Conclusion

The nightmare that Russia has unleashed on Ukraine is not yet over, so we cannot know how it will end. What we do know is that, however it ends, it will reshape, in ways large and small, the world that we all inhabit. There is no going back to the status quo ante. A war of territorial conquest, with incalculable losses, has again been initiated, and much will turn on how things unfold from here. The questions that governments around the globe should ask, and that their populations should insist on hearing the answers to, are about what vision they have for the future of the world order, what they are doing to secure it, and what cost they are willing to bear to try to achieve it. Because the stakes of their decisions in the course of this conflict are extremely high—especially for Ukrainians but for the rest of us, as well.