Literally

Although humans are capable of causing extinction, we currently lack the ability to do the opposite: structure society according to ecologically nonviolent practices. Most people usually fault a lack of political will based in a manipulative power structure of corporate financial interest. But what if what is holding humans back is the inability to understand interconnectedness, to practice relationships and representation at scales necessary to think ecology? What if our political structures, such as countries, are just too small to address an entire planet? Ecology proposes new understandings of human and nonhuman political collectivity, agency, affect, and narrative. These epistemic revolutions highlight the way ecology indicates new directions in understanding drama, a testing ground of human consequence. Theatre’s strange hybrid of literal and metaphorical meaning-making power has significant relevance to addressing climate change’s challenges to reality. An ecological approach to analyzing theatre must take account of how meaning and affect are produced through not only metaphorical signification but also the literal facticity and reality of materials onstage.

In the theatre, artists can prepare a show, but there is no way to control how the audience understands what they experience. The audience opens up the closed system of the performance to uncontrollable and indeterminable conditions, introducing what is known in both accounting and climate science as externalities, or unaccounted for consequences of actions. The audience brings with them what is outside the theatre, including political and ecological realities. What if the partitioned autonomy of modernism has been superseded by a new reality to a degree that the audience attaches meaning beyond the theatrical context? Just as climate change reminds us that action in one place affects life elsewhere, so too do events outside of the show change its meaning for the audience. My approach to analyzing theatre through ecological literalism is an inclusive mode of reading the meanings and affects of events onstage as impossible to separate from nonhuman conditions. Just as humans might have failed to realize the potential for colonial industrialization to cause suffering through global warming, so too might theatre-makers miss the ecological implications of their stage images. Articulating the ecological as an act of creative response is an urgent task of both political and aesthetic criticism if we are to have any chance of understanding the ecological interconnectedness necessary to reverse the trend toward extinction.

The political potency of aesthetic ambiguity is reconfigured in the theatrical landscape of contemporary life. Theatre’s literal and symbolic imbrication can help humans more deeply understand climate change and the complex scales of scientific uncertainty. At the same time a certain mode of theatricality is gaining political momentum in new contests between facts. By looking at particular moments in the theatre, we may find a way to articulate the modes of violent interconnectedness as a way to imagine different relations between humans and the more-than-human world. In both Caryl Churchill’s Escaped Alone (2016) and Richard Maxwell’s The Evening (2016), the moments I have chosen to focus on are exactly that: occasions to understand how the human is newly inscribed ecologically. I focus on particular scenes in each case study, beginning with Churchill’s explicit engagement with ecological issues. One character in Escaped Alone repeatedly steps out of the stage and forward into the auditorium; and I argue, into the horrifically real world of the audience.

Maxwell’s The Evening requires a greater leap of ecological thinking because there is little evidence that the artist intended to comment on environmental issues. I see an implied meaning to a single stage event at the end of the show. It is a movement out of the fiction of the world of the play, a disappearing into invisibility that is not only ecological but also intersects with race and colonialism—an extinction of whiteness. Postcolonial scholars including Julietta Singh (Reference Singh2018) and Malcolm Ferdinand ([Reference Ferdinand2019] 2022) as well as geographers such as Kathryn Yusoff (Reference Yusoff2018) have pointed out the ways in which colonial human activity prefigured certain kinds of violent relationships to the more-than-human world. Approaching theatrical representation literally takes account of what is and has been excluded from performance analysis by a focus on human action. Accounting for this history of exclusion is a move against the anthropocentric and colonial perspective that first excludes certain kinds of humans from basic rights before extending the same kind of brutality to the nonhuman world. I offer an original insight into understanding performance, race, and ecology as literally interconnected through studying scenes of theatre as they emerge between materiality and the immaterial. The significance of this research is to demonstrate how theatre can assist the political project of climate justice. As the art that is both of and beyond materiality, performance harbors radical potential for proposing literally new practices of relating to the world.

Figure 1. Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill. From left: Linda Bassett (Mrs. Jarrett); Deborah Findlay (Sally); Kika Markham (Lena); June Watson (Vi). The Royal Court Theatre, London, 21 January 2016. (Photo by Johan Persson/ArenaPal; www.arenapal.com)

Figure 2. Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill featuring Linda Bassett as Mrs. Jarrett. Directed by James Macdonald, designed by Miriam Buether, lighting designed by Peter Mumford. The Royal Court Theatre, London, 2016. (Photo by Johan Persson/ArenaPAL; www.arenapal.com)

Escaped Alone

In Churchill’s Escaped Alone the use of language in space and time is a kind of ecological event in which the human and its presumed place of dominance is questioned by the literally ecological collapse that is caused by humans but beyond our control. In Escaped Alone Churchill articulates an everyday sense of collapse. The meaning of the play has been critically investigated by other scholars, including Jen Harvie, who has analyzed the play’s feminist sense of age and time (Harvie Reference Harvie2018). My aim is a disavowal of intentionality grounded in a posthumanist critique of authorship as genius. I am interested in pointing to the ecological in places it might not immediately be obvious, taking inspiration from Mark Bould’s approach in The Anthropocene Unconscious, where he asks whether “fiction [must] be immediately and explicitly about climate change for it to be fiction about climate change” (2021:4).

Emphatically, no. The ecological is more of these theatre works than in them. My approach is literal in the sense that these events make use of the actual conditions of theatrical representation to make meaning in a time of climate collapse; it is literally ecological because meaning is produced through material connections that extend beyond the humanism of theatre. The significance of the scenes I analyze is multiplied by “post-theatrical” ecological conditions in a world of extreme weather events, climate suffering, and despair (post-theatrical because global warming is a lived experience rather than some deferred possibility). If climate change challenges how we humans understand ourselves, the theatre is a significant site to experience new versions of the human and the world in process. The excluded and the unimaginable can be repeated night after night for an audience who pays to see something other than daily life. Returning to Harvie’s reading of Escaped Alone, it makes sense as a feminist exploration of aging: for the majority of the piece, four women in their 70s sitting in a hyperreal back garden with an inordinately blue sky speak to each other about life. The conversations are fragmented and funny, touching and sometimes brutal. And yet separate from these friendly chats, there are two other registers of Churchill’s writing given clear scenographic designation by designer Miriam Buether and director James Macdonald: a second register occurs when each of the four women is under a spotlight to speak what sound like internal thoughts, while the other actors are in darkened stillness. This happens once per actor at different times in the show. When the general lighting returns and the four resume their conversation, there is no acknowledgment of what was said in the monologs. The third register of writing is represented through a significantly different scenography. The garden goes dark and one of the actors speaks directly to the audience in front of an electrified orange proscenium frame. This happens repeatedly with Mrs. Jarrett speaking, as she renders the total collapse of social, ecological, and political life in horrific and sometimes absurdly comedic detail. In her narration, the first monolog details an enormous rockslide that forces humans to adapt to a life underground. “Four hundred thousand tons of rock paid for by senior executives split off the hillside to smash through roofs

[…] Time passed. […] survivors underground developed skills of feeding off the dead and communicating with taps” (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:8). While Vicky Angelaki explains that in these monologs Mrs. Jarrett “vocalizes the narrative of society” (2017:25), I suggest that the scenography proposes a more complex layering of the fictive aspects of reality.

During Mrs. Jarrett’s speeches the plasticky hyperreal garden is placed in darkness and obscured by an electric frame of orange neon tube lights out of which she speaks directly to the audience. There are three layers of fiction: first, the illusionistic representation of realism in which the women speak with a recognizable sense of verisimilitude; second, the soliloquy when lighting darkens on three out of the four women while the other shares something too intimate for the polite conversation that is happening by the shed and plants; and the third order of address is somewhere else completely. The electric frame, which may be interpreted as the space of aesthetic appearance, is the only scenographic anchor—and yet the performer steps beyond the frame, into the room of the audience. The uncannily absurd narration of catastrophe that is spoken during these sections is most accurately understood not as the projection into an apocalyptic future but rather as a critique of our current ecological situation. Whether language can accurately describe reality is made uncertain through these monologs. Mrs. Jarrett steps out of the frame of the proscenium and literally into the auditorium, into the time and space of the audience to address their present reality. Using my literal approach: Mrs. Jarrett’s speeches are a direct address that entirely absents the fiction of the play to a degree that the monologs might be more accurately understood as spoken by the actor playing Mrs. Jarrett, Linda Bassett. The story she tells could easily be considered an imagined future apocalypse, were it not for the staging and the tense of the texts, as well as the actual weather that is literally outside of the drama in the streets. Just outside of the theatre (and inside too) is a real full-fledged Anthropocene of planetary crisis. There have been deadly rockslides caused by industries of extraction, and we communicate using taps on smart phones—but are we feeding off the dead? Is this a future imagined cannibalism or a critique of the meat industry? Is Churchill referencing necropolitics? The challenging aspect of understanding the mixture of theatre and actuality in these monologs is an attack on a transcendently ideological understanding of nature that obscures ecological issues (Morton Reference Morton2009). Multiplying Rebecca Schneider’s notion of how gesture can work in a “cross-temporal register” into a cross-theatrical or cross-factual register,

Mrs. Jarrett’s monologs float around the theatrical, the real, the present, the future, the imagined, and the actual (Schneider Reference Schneider2018:289). Mrs. Jarrett’s weird address breaks down the barriers that encapsulate theatrical reality, both the reality of the illusionistic theatre, and the reality of

illusion in denials of ecological collapse. The audience might itself be dislocated spatially and temporally by the material alteration brought about through ecological violence. Hearing Mrs. Jarrett’s words materializes the ecological agency of the audience. The audience begins to realize that the responsibility of ecology is a threat to a humanism that imagines itself as master of nature.

Literalism as an approach to theatre has been suggested by Una Chaudhuri, one of the first performance scholars to consider ecology. Chaudhuri was part of the group that composed the “Climate Lens Playbook,” a manifesto for ecological performance (Chaudhuri with members of Climate Lens 2023:42). The playbook begins with “1. Practice literalism. End the tradition of turning everything into a symbol for human life.” While Chaudhuri focuses on the habit of turning a nonhuman animal into a metaphorical vehicle for human traits, she hints at a general sense of literalism as a practice that creates the potential for ecological theatre. The literalism I practice in this article is a mode of analysis. This is to say that I am not necessarily identifying Churchill and Maxwell as theatre-makers who practice literalism. Instead, I understand the implications of particular moments of their work as implicitly having literal ecological import. Literalism is also useful for ecological interpretation because it provides access points to the material conditions of interconnectedness instead of focusing only on the fictional environment of the drama. Literalism materializes theatre while still leaving room for metaphorical meanings that enable an escape from the determinism of militant materialisms. The fictions of theatre still matter. As Chaudhuri poignantly announced in 1994, “By defining human existence as a seamless social web, naturalism was unwittingly acting out 19th-century humanism’s historical hostility to ecological realities” (1994:24). Critiquing theatre’s anthropocentrism is a start toward addressing its ecological potential. In Escaped Alone, this literal direct address chips away at a sense of our ecological reality as a stable experience of backgrounded environments and picturesque landscapes. My literalist ecological approach extends the meaning-making function of theatre beyond Chaudhuri’s critique of nonhuman animal representation; literalism can be understood as a way to notice how the material preconditions (as in the physical facts that illusionism asks the audience to ignore) of representation configure how theatre makes meaning in relation to a political aesthetics of ecology.

The relevance of this interpretation is multiplied by the way in which the violent effects of climate change seem almost unreal. The unintelligibility of climate collapse should come as no surprise, given that powerful forces have tried for decades to convince people to be at least skeptical if not to absolutely deny the reality of things like global warming. At a longer historical perspective, dominant human groups have assumed the environment to be a site of extraction and benign beauty. So although there is no direct evidence that this is Churchill’s intent, I understand the monologs describing catastrophe in Escaped Alone as attempts at narrating the literal ecological horror of the Anthropocene. The literal relation between the texts and the suffering caused by climate collapse operates in such a way that unpeels the layers of ideological fiction through which the material facts of life on earth are disturbingly obscured through being naturalized. Directing and scenography transform the theatricality of the play’s text into words literally resonant with the effects and affects of the climate crisis. When the garden is darkened, Mrs. Jarrett might as well now be Linda Bassett, talking to us in the audience about the way in which ecology affects language. The show proposes a new literally theatrical poetics of horrific ecological crisis. Escaped Alone utilizes illusionistic theatricality to such a degree that the theatre of the planet is made briefly available through language as a violently horrific process: “Fire broke out in ten places at once. […] Houses exploded. Some shot flaming swans, some shot their children” (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:37). The dangerous conditions described in the monologs are indirectly a result of the artificial safety of the back garden. Fossil fuels produce both luxury and damage; the group of women do not see what is described. It should come as no surprise that a complex ecological aesthetic emerges from a playwright whose work has long experimented with how to think about what exists beyond the human.

Chaudhuri has held up Caryl Churchill’s writing as a prime example of ecological theatre.

In The Stage Lives of Animals: Zooesis and Performance (2017), Chaudhuri focuses on the representation of nonhuman animals in Churchill’s Far Away (2000). International human conflict in the play spills over into the more-than-human world, with certain animals siding with certain countries. Cats become allies of France, and even the weather gets involved, joining the Japanese in the fight. Chaudhuri explains that Churchill shows a world in which nonhumans “act along with yet independently of” humans (2017:43). This is not a situation where humans control the more-than-human. At the same time, the more-than-human seem to have no choice but to be brought into the human conflict. Chaudhuri explains that in Far Away Churchill “rigorously desentimentalizes the animal” (39). Not only are these nonhumans acting alongside and independently, they are also fighting violently. This is a representation very far away from the cute animals of popular culture that are domesticated even beyond designating them as agricultural material; cute pets that exist purely to comfort the human, affection machines (not unlike my own pug whose name is Chicken). Chaudhuri appreciates Churchill’s rigor precisely because it recognizes the harm of turning the animal into something that could never possibly be political. Chaudhuri explains that “the trivializing of the animal in contemporary culture may be harder to combat than overt hatred would be” (39). Even animal activism that metaphorically speaks for animals might be said to be another obstacle preventing us from being able to apprehend what animals might want to communicate to us. The ecological solidarity between humans and nonhumans in Far Away is rendered in Churchill’s Escaped Alone as clear, sober reportage of the suffering caused by environmental and climate collapse.

The reports of catastrophe in the play resist the idea that humanity has already and will ultimately transcend nature. Instead, strange statements, such as “the baths overflowed as water was deliberately wasted in a campaign to punish the thirsty,” propose an unreal theatricality as an antidote to the audience’s naturalized but fictitious sense of ecological actuality (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:12). We have been comforted so far by the idea that one by one people will gather the political will to implement enough of the many thousands of solutions to climate change to make a difference. The chaotically unfolding disaster described in the monologs reveals the slow pace of ecologically sound political development as horrifically inadequate compared with the acceleration of destruction. The symbolic power of individual action for a planet-wide collective problem might even be an obstacle to political global transformation. Consumerist lifestyle alterations by members of the global north’s middle class might only replace guilt with righteousness, obscuring the possibility of potent political change. The monologs in Escaped Alone propose a fantasy of human mastery at the heart of that story, and the difficulty presented in the monologs show solidarity with people and nonhumans for whom the suffering caused by habitat destruction, pollution, and climate collapse has already been occurring for a long time on a horrifically violent scale.

The monologs do not only remain in the present of the theatrical event, but refer back and forward to different times. As they recount events in the past, they also take the audience to their own pasts: “Smartphones were distributed by charities when rice ran out, so the dying could watch cooking” (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:22). Just as the monologs challenge the temporality of presentism of performance, so does ecological reality remove the earth from concepts of space and time. Linear time and history itself is up for debate, as these narrations concretize the ecological reality of human and more-than-human life. “The logic of approaching pasts in the reiterative waves of gestural call and response might allow for making palpable the alternative futures that responses otherwise to those so-called pasts might have realized—or better, might yet realize” (Schneider Reference Schneider2018:305). Ecological time is a critique of the implicitly humanist idea of sustainability, which obscures the fact that life must change for planetary survival. Mrs. Jarrett lays out this different world in impossible clarity. Some details are horrific beyond belief, and yet these speeches are very close to actual ecological events such as birth defects from chemical waste, rockslides caused by extraction of fossil fuels, and extreme weather: “The chemicals leaked through cracks in the money. The first symptoms were irritability and nausea. Domestic violence increased and there were incidents on the underground” (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:17). Is articulating these events such an apocalyptic stretch from what has been occurring on earth in the Anthropocene? Or is it that Churchill is addressing political ecology as a literal horror that is already happening? To see these descriptions as an imagined future apocalypse might be the artificial theatricality of a perspective on ecology that situates the human as in control no matter what. Churchill’s work is proposing that the literal materiality of ecology demands a different approach to the theatrical realities of the stage and the world.

The theatrical narration of catastrophe is absurd. The literal events themselves challenge the language system’s ability to communicate the true experience of apocalypse. “The wind developed by property developers started as breezes on cheeks and soon turned heads inside out. […] Buildings migrated from London to Lahore, Kyoto to Kansas City, and survivors were interned for having no travel documents” (28). Language stops making sense when scientific certainty in the stability of the environment is shattered. This critical appreciation of the limit of language intersects with a postcolonial challenge to language and aesthetics as forms of subjugation. There is something colonial in the double bind that traps the human in the perception of humanity as savior, which places the human above the nonhuman in a speciesist hierarchy. My approach to literalism builds on the work of theorist Julietta Singh who in Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements explains her understanding of literalist analysis as “a dehumanist education through which ‘subject matter’ comes not merely to describe a topic of study but to signal the physical matter that makes study possible” (2018:67). Singh offers a sense of literalism as a practice that is attuned to the material conditions of history and thinking. Not unlike Fred Moten (Reference Moten2003:1), Singh shows how subjects can be treated as objects. Singh suggests that the colonial articulation of indigeneity and animality is tied to a reinforcement of anthropocentrism. She warns against an anticolonial move toward humanist mastery that ends up reinforcing colonial structures. Instead, she advocates for a rejection of mastery that would in fact “mobilise one’s animality […] to dispossess oneself from the sovereignty of man” (2018:122). Instead of acting still more anthropocentric by trying to save the animals or to maintain our current scientific and linguistic understanding of the world, we might experiment with a political aesthetic that disassembles our constructed human relation to the more-than-human world. Likewise, the humans in Caryl Churchill’s Far Away are joined by the animals as they become a part of the fight. The environment in Escaped Alone riots against the human order that subjugates all of the earth as objectified resource.

Where Singh demonstrates how colonial symbolism oppresses through an exclusive mode of knowledge, my approach to literalism shows how the human can experiment with new semiotic forms to articulate inclusive solidarity with more humans and nonhumans. Understanding these aesthetic experimentations literally will necessitate the development of new forms of language, aesthetics, and science to catch up with the changes of the material world. The human continues to evolve. Churchill’s aesthetic politics propose deeply significant reconfigurations of ecological relations. In Mrs. Jarrett’s monologs, the language of uncertainty dramatizes the instability of the environment in an implicit refutation of the colonial logic of containment and extraction without cost. The monologs imply an anticolonial ecology of a language and environment that exceeds human control and understanding. The second speech concerns a great flood. Churchill again accesses the nonhuman as a kind of participant in human events, writing that the ponies “huddled with the tourists” (2016:12). Then, again, there is more horror and death: “Some died of thirst, some of drinking the water” (12). Absurd as they might sound, these are events that do happen. There are, however, other events described that have not happened, at least to my knowledge, such as that “drowned bodies were piled up to block doors”; or, even more unfamiliar, that the young “caught seagulls with kites” (12), presumably to eat them. Even though these images are unfamiliar, isn’t there the possibility that they are accurate? If so, perhaps Churchill is suggesting that much of the lived experience of the world is being performed invisibly, metaphorically backstage, as too much of life does not meet the conditions of reality expected by hegemonic capital.

Mrs. Jarrett’s monologs describe a vertiginous collapse of everything. Were it not for the straightforward clarity of language and staging, these texts might be seen as unrecognizably absurdist poetry. Perhaps Churchill is suggesting that there is in our apprehension of ecological reality a seductive and politically potent current of fiction even in the most recognizable of scenarios. This might be a different kind of speech altogether from the more recognizable descriptions of life such as weather and politics that imagines a transparent storyteller, full of authority. The hybrid Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett is an example of a reporter of ecological narratives making use of language that is not seeking mastery. Nonmasterful language resists a colonial sensibility that wishes to understand environments only as they serve certain humans. Julietta Singh’s work offers a path toward understanding how the uncertainty of the literal and metaphorical in these monologs might be interpenetrating in such a way that resists mastery as authoritative brutality in the symbolic realm of politics. Singh explains that “What the language of mastery does is to enforce legacies of violence,” which is to say that taking up the position of the master, knowingly or not, produces the slave (2018:66). The assumption of knowledge superior to that of the colonized subject provided some of the arguments needed to build empires. Singh proposes that attempting to inhabit forms of mastery even for postcolonial subjects will never do more than repeat violence. She extends the critique of mastery even as far as academic study. “To believe that mastery (of texts or languages) is possible, and to desire such mastery, solidifies our complicity with the very source of imperialism that so many intellectuals and activists are wont to resist” (2018:89). This is to say that one kind of actively decolonial work—to resist continuing aftereffects of the history of colonialism—involves refusing the ideological structures provided by historical colonists. The path of emancipation through mastery is the extension of rights, freedoms, and so on to the oppressed in order that they might be remade in the shape of the colonist. In other words, Singh is pointing out the absurdity of trying to repair the injustices of colonialism by turning everyone into a colonist. Singh’s quite important alternative is to suggest what she calls a vulnerable reading, in which the subject is constantly dispossessed of individual mastery and repositioned in relation to wider collectives of interdependency. Might Churchill’s texts be understood as a deeply vulnerable reading of the Anthropocene? Might they be read as an attempt to see the horror of ecological collapse as it has been happening without the comforts of the ideology of human mastery that will transcend and eventually overcome nature again? Just as colonialism is complicit with an extractive ecological regime, a decolonial critique of mastery is a part of the critical mass of progressive forces that also includes ecological adaptations that make collective survival possible.

The unbelievable parts of what Linda Bassett/Mrs. Jarrett says are included because the other more believable events are themselves challenges to a Holocene worldview that takes for granted the ability to farm crops, enslave populations, domesticate animals, and burn fossil fuels without the consequence of extinction. Taken literally, these monologs mark the alteration of the human subject by nature, a dispossession of the same colonial mastery that subjugated both people and the more than human. The Anthropocene and its accompanying biodiversity collapse, extreme weather, and extinction events are all environmental horrors of certain humans’ making. What is difficult to unpack is how the catastrophe is predicated on human action but not human intention. The human becomes a subject deeply reconfigured by the sense of responsibility without control; a subject able to cause destruction through a misleading sense of mastery. The horror is multiplied by the degrees of interconnectedness, which means that there is literally no certain escape from ecological difficulty. Humans might learn what made things go wrong, but there is no guarantee that we possess the ability to make things right when we are dealing with forces that cannot be controlled.

This kind of othered subjecthood is hinted at in Churchill’s title, spoken by the biblical character Job, also cited in Melville’s Moby Dick. To have escaped alone is what allows the tale to be told. Like Ishmael, Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett sees what is happening to the earth and reports it. The register of the language also means that the catastrophe is partly in the past. This is where the ecology of the Anthropocene is a problem for understanding time and space in relation to subjecthood. It is accepted that the material world has effects on our inner lives, but in the Anthropocene the new addition is that we are seeing the harm caused by what was once presumed innocent. This is not limited to industrialized farming, driving cars, or eating meat; the revelation extends to politics that are now obsolete, such as the grossly inadequate attention paid by nation-states to climate. The violent upheaval of the Anthropocene is even a challenge to philosophy. As Carl Lavery has explained in his divergence from Heidegger’s thinking, “ecology is a mode of operating that troubles the contours of the human subject by revealing the extent to which the entwined concepts of homecoming and dwelling are not only philosophically dubious but environmentally and socially harmful” (2018:12). It is possible to understand certain philosophies, such as Heidegger’s, as connected to violent modes of ecological relation between humans and environments. The ideas of the beautiful landscape, benign weather, and endlessly profitable natural resources are no longer tenable. Lived experience contradicts the false reassurances of extractive capital and its accomplices. Knowledge too is affected by global warming. Climate change is real, and it will get worse. We cannot know how much worse, but we have learned that what we have done and how we have lived makes changes in the environment go in a certain direction. As Jem Bendell, a researcher in sustainability, has explained: “It is difficult to predict future impacts. But it is more difficult not to predict them” ([2018] 2020). Part of this disconnect is brought about by years of misinformation dished out by profit-driven corporations and their accomplices. Mainstream media has only recently begun to connect extreme weather events to climate change. There persists a sense of constant ecological deferral that allows us to believe that mass extinction and global warming will continue to be far enough away that we will not have to think about them in our personal lives. While Churchill’s monologs are often describing events at a planetary scale, at other times they jump down to the scale of the individual, the personal, and the everyday. “Governments cleansed infected areas and made deals with allies to bomb each other’s capitals” (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:29); as leaking chemicals begin to effect residents,

Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett also explains how people could wait months for a National Health Service gas mask or buy one from a private company and choose a mask in their favorite color (17). The Royal Court Theatre marketed the play as “tea and catastrophe,” which neatly pairs the seriousness of collapse with the everyday (Royal Court Theatre 2016).

The proximity to ecologically related suffering is not the same for everyone. For many people, catastrophe has been an ongoing reality for too long. Horrific scenes that people have experienced are too often excluded from public discourse and memory. Kathryn Yusoff’s A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (2018) suggests that the uniquely global magnitude of the genocide and enslavement of African and diasporic populations was itself already human activity on a geological scale. This is not ecological violence as equivalent to racism, this is a racism that predetermined the ecological violence that would follow. The violence of the slave trade inscribes antiblack inhumanity on the stratigraphy of the earth through the violent relation of extraction that slavery modeled for nonhuman resources. The experience of the collapse of the world is nothing new for communities who have resisted annihilation. The horrors of the Anthropocene only seem new and extraordinary to a perspective of reality that seeks to minimize the ongoing histories of colonial violence. The perspective that creates the violence is exactly the one that seeks to minimize it. On the other hand, the subject who has escaped alone, who has lived through the catastrophe, speaks from a position of resistant survival as an alternative to the subject of mastery, who continues to seek out control. The kind of human subjecthood that Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett is performing is one in which the ability to do harm is not balanced or rectified by the ability to save or know that good will come. Her narration of ecological catastrophe is not one that finds resolution in masculine techno-solutionism. Her monologs illustrate that catastrophe is of the everyday rather than an exception to be corrected by more of the same human behavior. This correction of reality is an insight produced through an examination of the tensions between reality and theatricality. The force of accuracy literally undercuts the transcendent structure of metaphor. An ecological approach to performance studies rematerializes theatre beyond the anthropocentricity of metaphorical representation. Aesthetic innovations in performance that destabilize theatrical artificiality inform a politics of ecological literalism that challenges the reality and facticity of relations between humans and the environment. In Escaped Alone Churchill proposes an entirely new function of theatre in an age of ecological catastrophe: one where material injustice is made visible, literally in front of the illusionistic veneer of representation. The hybridized Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett performs the new position of the vulnerable subject resisting the violence of the Anthropocene. She speaks with the audience about events that hint at the limits of representation, not because the events are not real, but so that the audience can consider how linguistic representation is limited by power structures whose interest is to maintain the status quo. Understanding contemporary ecology requires new modes of representation.

The language and scenography of Escaped Alone invite the audience to consider how ecological politics are always already produced through processes of theatricality that obscure the materiality of things so that metaphor becomes transcendent. This play plunges the audience into the necessarily difficult uncertainty of realizing the insufficient linguistic aesthetic of old models and the need for completely new forms of knowledge to understand the current unprecedented political and ecological reality. My analysis suggests a literal turn in performance studies that identifies a specificity in the energetic power of lived aesthetic experience to make meaning by appealing to the potent materiality of ecological relationships, not by transcending matter to the abstract structures of metaphor.

Figure 3. The Evening by Richard Maxwell. From left: Brian Mendes as Asi; Jim Fletcher as Cosmo; Cammisa Buerhaus as Beatrice. Directed by Maxwell; designed by Sascha Van Riel. Théâtre National, Brussels, 2016. (Courtesy of Richard Maxwell)

The Evening

Richard Maxwell and the New York City Players’ 2016 production of The Evening begins with a letter detailing the last days of Maxwell’s father’s life. It is read by Cammisa Buerhaus, who plays Beatrice. The drama that unfolds includes two other characters, Cosmo and Asi, played by Jim Fletcher and Brian Mendes. In dialog the characters refer to each other using the names Bea, Cosmo, and Asi, but the play text itself attributes lines to the actors’ names.

CAMMISA, as bartender, is behind the bar doing her thing. After a moment, JIM enters in coat with a pizza box.

JIM: Hey Bea. (Gives her kiss, removes his coat and sits down. He opens his pizza box and takes a bite. BRIAN enters in parka.)

BRIAN: Hello, Cosmo.

JIM: Asi! Congratulations my brother! (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2016:4)

The naming of actors in the script signals to the literalist a theatrical hybridity of actor/character that I attributed to Escaped Alone but is more explicitly at work in The Evening. While literalism is more aesthetically established in Maxwell’s practice, the ecological only really appears at the end of the show. One notable aspect of the fictional drama that precedes the literalist ending of the performance is that its characters and place are working class. This is not the abstracted or autonomous aesthetic zone of some experimental theatres. Performed as a part of European experimental theatre festivals such as Kunstenfestivaldesarts, where I saw the show, The Evening presents its audience with a milieu that is distant in national, cultural, and political-economic identity. These characters are concerned with what they see as immediately important. They dream of travel as escape from exploitative material labor, even if this discourse is not framed as an analysis of political economy. They certainly are not talking about climate change. Bea, Cosmo, and Asi might be the kind of people who would rather have Jello shots and argue about football than sip wine and discuss the latest global temperature rise. The confrontation of this American working-class milieu with a cosmopolitan European audience is already a challenge for identificatory spectatorship.

The set designed by Sascha Van Riel is recognizable as an American dive bar, with simple tables and chairs, and a football game playing on the wall-mounted TV above the bar. The acting space is strikingly shallow and far downstage; the white working class is placed uncomfortably close to an audience that is possibly unwilling to identify with them. Although the fiction of the play says little to nothing explicitly about ecology, a literally ecological analysis includes what is apparently outside the play, including the audience. In The Evening, the audience is confronted with the political failure to muster the level of collectivity necessary to enact decisive political consensus on a range of issues including climate change and biodiversity loss. The affluent liberals in the audience of experimental theatre must admit some culpability for their exclusion of the white working class from their political reality, even as the white working class too often excludes itself from serious conversations about climate justice in its complex relationships to other forms of social justice. This is all to say that it is surprising to encounter the white working class, even as characters, in a space that is not always in solidarity with them.

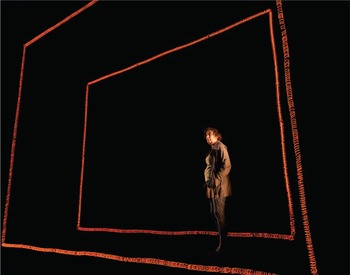

Figure 4. The Evening by Richard Maxwell. Cammisa Buerhaus as Beatrice, barely visible in the haze. Directed by Maxwell; designed by Sascha Van Riel. Théâtre National, Brussels, 2016. (Courtesy of Richard Maxwell)

All the more beguiling then is the literal ecological turn the play takes at the end. Late in the performance, a band enters and plays some songs that explore the feelings of the characters. As a kind of climax, Beatrice shoots Asi and Cosmo. Stage blood spurts from their wounds. The actors remove the pouches containing the fake blood. The production makes its turn to the literal. Stagehands enter and take away the pouches of blood, the gun, and the pizza box as the band plays and the actors watch. During the final song, the actors Jim Fletcher and Brian Mendes exit while the stagehands continue their work. Surprisingly, the stagehands remove all of what had been the set including the tables, the chairs, and then the walls. The whole room is carried offstage. A thick haze of stage smoke fills the now gapingly large and bright white room. This is not wisps of vapor but a truly thick haze that comes from nowhere in particular and yet fills the stage. A stagehand gives Beatrice, who may be literally both the character Beatrice and the actor Cammisa, a warm coat. She speaks but can barely be seen. The human is both there and not there, obscured beyond recognition. Was this opaque atmosphere behind the backdrop of the bar for the entirety of the preceding action? Is this visible air the escape that Beatrice/Cammisa was looking for? Or is this an environmental shift toward the literal? Perhaps both: the backlash of the atmosphere against an all too human attempt to aestheticize and placate nature. This moment is literally a deconstruction of life as we know it and the blurring of identity among nonhuman material. The image of Beatrice/Cammisa disappearing into the thick haze of stage smoke is ambiguous because it is literally outside the social drama of the bar. As I mentioned earlier, Mark Bould shows how the Anthropocene becomes the subconscious of artistic representation, which is partly why ecological images can be so difficult to interpret: “Metaphor is powered by contradictory impulses and energies” (2021:119). I have already discussed the political and economic forces that push the ecological into the subconscious. With Bould, I am interested in the contradictory energies of ecological meaning, and yet my focus is on how these meanings precede the metaphorical and appear already in the literal. Is Beatrice/Cammisa choosing to disappear or is this nonhuman material, the haze, consuming her? She says a few last lines and moves away from the audience until she becomes invisible.

The materiality of the stage becomes potent with a new order of meaning on a scale beyond the social concerns expressed in the bar. The hazy smoke literally exceeds what was contained within the drama of the play. The literal arrival of the atmospheric nonhumanity stretches the scale of meaning of Maxwell’s piece. This is no longer a recognizable human environment. It is a fog, a haze, and so could be polluted air—and it has eclipsed the human completely. This is more than Carl Lavery’s “ecological image” that he finds in theatre that shows “human beings as both central and superfluous to the fate of the planet” (2013:275). In Lavery’s writing on the work of Philippe Quesne, the image’s “gratuity” and “facticity” work toward “encouraging the audience to engage in its own act of ecological interpretation” (274). In The Evening, the thickness of the haze is gratuitous in how much it obscures the figure of the human. It is too much smoke. The image overtakes Lavery’s framework because Beatrice/Cammisa is no longer both central and superfluous; she is lost. Therefore, this is a moment of opacity in which the ecological implication is a matter of imagination rather than an inherent proposition.

Along with Claire Colebrook I experience the haze as “imagination without image,” or a way of reading even “if we were not to assume some ultimate readability or spirit beneath the materiality of text” (2016:123–24). Colebrook suggests that artistic images live beyond the intentions of the artist through the ever-changing materiality of their manifestation. In this hazy moment the thickness of the smoke is literally a representation of the disappearance of the human. The question is whether this disappearance should be understood in the context of the Anthropocene as the extinction of humankind in a toxic environment or, in a more hopeful register, the ending of a kind of humanity that causes the atmosphere to become unlivable. If the latter, the moment signals a possible transformation of human subjectivity capable of ecological justice. The dismantling of the stage set suggests that the haze can be understood as existing in an entirely different mode of the social that now includes the ecological. The stage becomes representative of a place of meaning that is aired in the awakening ecological reality of extinction. The human is invisible; the haze is all that can be seen. The moment is full of ecological potential when considered in relation to the climate outside of the theatre. Perhaps the stage smoke is a literal manifestation of one possibility of the Anthropocene, where all that exists is pollution. An anthropocentric lens would see nothing onstage, but that would render invisible what is literally there: the haze.

Any attempt to understand the possible meanings of this image invites an ecological interpretation because of the inhumanity of the image. Therefore, is the image an ecological situation without humans? If so, is it a flat white Anthropocene of toxic gas? Or a new space of interconnectedness that is only invisible according to the contours and outlines of contemporary subjectivity? The latter interpretation is a less cynical possibility that, understood alongside the white color of the smoke, can point toward a sense of collective solidarity that could emerge from both ecological and racial justice. More than a disassembly of anthropocentric realism, I argue that this moment of the construction of one kind of invisibility has not only ecological but also racial and postcolonial political implications. To understand how such a meaning can be interpreted in this way, it is necessary to understand Maxwell’s practice as a historical investigation of the boundaries of theatricality.

Richard Maxwell and his New York City Players emerged from the postdramatic tradition of companies like The Wooster Group and Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theatre. Maxwell’s revisionist approach resides in the idiosyncratic refusal to participate in an illusionist realism that attempts to reject the actual, even as he invests in the practices of dramatic literature. Working in and around that paradox stemmed from a discovery Maxwell made in rehearsal for an early production. He spoke about this in a talk at The New School where he explained the importance of working with “The notion of saying ‘no’ onstage as opposed to the improv pedagogy of always say yes” (in

The New School 2016). Negation and refusal are common traits of the avantgarde, but Maxwell’s is a gentle no. His refusal is an opportunity to turn toward a new mode of representation. Maxwell wants to provide experiences where questions are a part of the theatrical process.

The audience member in the theatre watches the stage and is presented with a question, “What is this thing happening before me?” It’s real and it’s fake—this room, this set, this person, this story. In this room there is accountability all around and on both sides of the footlights. (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2015:3)

Maxwell investigates a porous interplay between the real and the fiction and it becomes a question of responsibility. In The Theatre of Richard Maxwell and the New York City Players, Sarah Gorman explains that the work is exactly about the “slippage between the hermeneutic world of the plays and the auditorium” (2011:116). Maxwell’s practice is not merely a rejection of illusion, but rather an exploration of illusion in relation to fact. Gorman goes on to explore how Maxwell directs actors to experiment with facticity and illusion through performance.

Pivoting away from a temptation to describe Maxwell’s performers as deadpan, Gorman opposes the performance style of the New York City Players to the early 20th-century practice of method acting, and even identifies an ecological antihumanist potential lurking alongside the political implications of this approach to performance: “Maxwell’s work acts as a critique of the Humanist values of Method-training by demonstrating how it requires actors to ignore the reality of their immediate socio-cultural environment in order to imagine themselves into an absent, fictional reality” (2011:34). By refusing to purely transcend the here and now, Maxwell returns the literal to the theatre. Through materiality, Maxwell’s practice contains the potential for a posthumanist dramatic theatre. His experimentation with fact and fiction in representation reveals the human as interdependent within networks of material conditions. The political potential of the rejection of illusionistic humanism is embodied in the materiality of the actor’s labor. It is an interdependence that extends beyond the social and the human. The literal materiality of the actor is part of not only what is inside the auditorium but also the rest of what is outside the dramatic theatre. The literal does not avoid the world. In Maxwell’s work, this experiment is not merely in directing and acting, but also in design. In Theater for Beginners, Maxwell explains:

The designer of the theatre set has to draw the line between “the fake” and “the real.” […] In a theatre, the wing space, the ceiling, the chandelier above the audience’s heads, the black walls—these are objects not necessarily considered part of the fiction, yet they are visible. These features matter to the set designer and they feature in the design. (2015:32)

Productions by Maxwell and the New York City Players make use of multiple elements of theatrical representation to investigate the relations between the real and the fiction in dramatic performance. Even the fictional worlds of Maxwell’s plays, Gorman explains, “show free will to be something of an illusion” (2011:39)—a common theme of drama, yet in Maxwell it is amplified by the representational performance style.

Maxwell’s work therefore presents an occasion to literally analyze the bodies of the actors and their material embeddedness in structures of meaning beyond the fictitious social drama. The Evening becomes more politically potent, not less, when understood literally as materially dependent on the multiple preconditions of ecological relations and their histories. One narrative in the history of the Anthropocene and its violence tells how humanism constructs its senses of mastery, freedom, and scientific facticity through the exploitation of excluded subjectivities and objects. Enlightenment humanism takes for granted an implicit exclusion of racialized subjects. So even though race is not biological, it takes on a material reality in contemporary life. An ecological theatricality offers a way to understand the covalent artificiality and materiality of what comes to be seen as reality, in terms of both race and ecology. The separation of race and ecology might be just the problem that prevents either from moving past their violent configurations.

By separating environmental critiques on the one hand from antislavery and anticolonial critiques on the other, environmentalism embodies a colonial ecology: an ecology whose function it is to preserve colonial inhabitation and the forms of human and nonhuman domination that come with it. (Ferdinand 2022:115)

Separating the human effects of racialization and colonialism from how these human processes also interact violently with the nonhuman world is an obstacle to developing a realizable politics of decolonial justice. The facticity of interconnectedness when considering theatre in ecological terms reveals intersections with race and interconnected histories of postcolonialism. If dominant populations of humanity operate within an extractive colonial mode of exploitation for the sake of private capital accumulation, a predictable set of outcomes will occur: a planet warming at an alarming rate that produces suffering through extreme weather, biodiversity loss, and cascading extinction events. Such planetary and historical scales are difficult, but not impossible, to recognize in the relatively smaller scale of theatre.

How might these wider contours precondition the literal apprehension of the haze at the end of The Evening? The interrelated histories of ecological exploitation and racialized colonial extraction frame how the haze obscures the individual. But how is this nonhuman haze related to a history of racialized exploitation? To be clear, Maxwell is white, and all three of the actors are white. Nothing is said of their whiteness in the play. I argue though that their whiteness should be understood as a literal precondition of The Evening’s ability to make meaning. Whiteness and its relation to inhumanity is a recoverable feature of literally ecological theatre. In a program note, Maxwell discusses his interest in representing types of people to allow the stage action to go further than reality, such as Asi/Brian as the professional mixed martial arts “fighter”: “I’m looking at what the difference is between a person and a character” (in Benson and Maxwell Reference Benson and Maxwell2015:17). Cammisa is a bartender and sex worker and Cosmo is Asi’s corrupt manager. That a play of types consists of an all-white cast speaks to the certain role whiteness plays as both the all-too-visible norm of a racist culture of exclusion and at the same time the invisible neutrality of the enduring type. In this production whiteness is an implicit prerequisite for the representation of type. Whiteness here is innocently accidental in the play, its dominance an externality of an antiblack culture that makes whiteness an invisible, normal aspect of some cultural production. In this paradoxical situation, whiteness is both everywhere and neutral. However, in Maxwell’s The Theater Years, he reveals a more nuanced understanding of the political valence of neutrality, which I propose is a theatrical effect partially achieved through a logic of racism. Maxwell intentionally disturbs “the concept of neutrality onstage, if only because of its utter futility. […] What color is more neutral, white or black? Most theatres are painted black to become neutral, not considering what it means for a black performer to be in front of a white audience” (2015:15). This literalism admits to the facticity of race in such a way that resists new kinds of polite racism, such as colorblind casting, that ignore the lived experience of racialization. And yet Maxwell engages in a mode of thinking with whiteness as central; the quote above assumes the audience is white, as is he and the three actors in The Evening. One might go so far as to suggest here that the dominance of whiteness is grounded in how its visible dominance is masked by invisible neutrality. Resisting this racism through implicit exclusion via neutrality is not as simple as increasing the visibility of black, indigenous, and other people of color. Independent art critic Zarina Muhammad of the White Pube has explained in her seminal text, “The Problem with Representation,” that simply diversifying the content and programming culture produced by racialized people might only obscure the structures of inequality that usually result in exclusion (2019). Too often the representational, allied as it is with metaphor, occludes the supposedly invisible literal material conditions of structural systems. Moreover, it is important to be cautious about whether visibility and representation are themselves always beneficial. Noting a further externality of being included in the realm of the visible, Anne Boyer discusses how gaining more representation might be dangerous:

It’s probably obvious now that many aspects of experience are so visible and yet many conditions are worse, such struggled-for awareness mostly a disappointing variable of acquiescence, struggled for again and again, only to disappoint again as newly ordinary. Visibility doesn’t reliably change the relations of power to who or what is visible except insofar as visible prey are easier to hunt. (2019:159)

While antiblack racism can be said to cause a portrayal of generic types by an all-white cast, imagining naively that a more diverse group of performers would somehow result in the dismantling of antiblack racism is a fantasy of representational politics. Too many white artists default to this easy solutionism and thereby avoid questioning the hazy, barely visible structures of power. Just as Julietta Singh warns against postcolonial political projects that reinscribe colonial mastery as a false emancipation, I argue that the connection made between whiteness and invisibility is an implicit but powerful antiracist critique in the materiality at the end of The Evening. The nonhuman haze of whiteness on Maxwell’s stage is an occasion to identify an intersection between racism and ecology. This is not a moment of increasing visibility for anyone; it is the reduction of visibility, or centrality, for certain people.

The literally ecological point of this haze is that it is a nonhuman material that becomes whiteness to check its purported corporeal neutrality. This provides a path toward redefining whiteness. Attending to the ecological literalism of this image means taking seriously other-than-human whiteness as an ending—without humanity. If my analysis reads as a return of the metaphorical, that is only because signification has too long been seen as a process of dematerialization. Literalism paradoxically finds meaning through returning to the materiality and corporeality of the production of action in performance. The Evening presents its audience with a violent death of two characters, Asi and Cosmo, followed by a calm exit of the two actors Brian and Jim who portrayed those characters. The third figure, Beatrice/Cammisa, disappears into the haze. In an Anthropocene rife with extinction, is this yet another dying out? Is the disappearance of these three a prelude to extinction? I understand this theatrical disappearance as an occasion to consider how “neutral whiteness” might itself go extinct through the operations of both ecological and racial justice.

One aspect of understanding the interconnectedness of race and ecology is realizing the possibility to attribute responsibility for ecological collapse in specific ways. Not everyone shares equal responsibility for the biodiversity loss caused by global warming, and there is a racial dimension to the differentiation of ecological harm. Since the industrial revolution, the acceleration of harmful emissions has only recently been roughly equal on a global scale, affecting multiple races, ethnicities, nationalities. Historically, the colonial empires of white Europe, and subsequently the US, are responsible for most of the planetary pollution caused by industries powered by fossil fuels. Yet as other countries gain the capital and technology to outstrip the global north as the worst polluters, it is possible that an ahistorical connection between global warming and colonial whiteness as the problem seems less convincing. However, the extension of pollutive capability to countries such as India and China might in fact be evidence that the accumulation of extractive colonial capital has more to do with the subjectivity that history came to call whiteness than with the people who lay claim to embody this identity. And yet, whiteness still works as a shorthand for differentiating between nation-states that have benefited from industrialization over the past 200 years. Because of how profits have been unequally distributed, the United Nations has had its most difficult disagreements over attributing differential responsibility for the costs of climate change. Understanding these kinds of planetary relations as colonial hangovers invested in a kind of whiteness provides a route toward environmental justice. The possibility of a world without over-pollution might be just as unimaginable as a world without whiteness; seeing whiteness and pollution as interconnected provides suggestions for understanding how to enact wide-ranging global justice.

That such a complex problem can be interpreted in the literally hazy disappearance of an actor is indicative of a historically specific situation in which contested realities create confusion. The difficulty of understanding ecological justice is related to understanding the environment as separable from other registers of life. Analyzing the relations of colonialism might clarify the simultaneously intersecting ecological relations. Moreover, theorists of colonialism have also demonstrated the importance of understanding that which is beyond the grasp of hegemonic knowledge systems. For example, the disappearance of Beatrice/Cammisa is also the appearance of the nonhuman. Pointing only at the lack of the human obscures the theatre’s ability to function as a space for the appearance of nonhumanity and the posthuman. Seeing difference as unclear and understanding the limits of language points to new modes of political solidarity. In Poetics of Relation Edouard Glissant provides a framework for understanding the limits of the visible in relation to agency: “The opaque is not the obscure, though it is possible for it to be so and be accepted as such. It is that which cannot be reduced, which is the most perennial guarantee of participation and confluence” (1997:191). Glissant’s opacity is a condition of relation, in which a heterogeneity includes parts that are not necessarily subsumable into a whole. Opaque relations precede the imperative for a transcendental subject that identifies legibility. The relation between race and ecology is opaque, in the sense that there is evolving interdependence between them.

The relevance of Glissant’s opacity is the possibility of the irreducibility of Maxwell’s image.

A nonhuman haze of almost complete opacity obscures the figure of a white actor/character. She nearly disappears and yet a new figure in relation to a nonhuman matrix becomes visible.

The poetic register of this ending bears little to no relation to the human scale of the drama that precedes the haze. Understanding this theatrical event is an opportunity to extend its meaning toward its literal materiality. In this mode of analysis, there is more, not less, to actions onstage than what the makers of the performance intend. The stage can never fully extinguish the interruption of factual externalities, just as the effects and costs of climate change are unavoidable. This contingency and lack of containment literally operates as a political feature of the postcolonial subject who is always in relation to other subjects excluded from dominant legibility. For Glissant interconnectedness is only materially possible if radically open to the addition of excluded others and new modes of togetherness:

We have suggested that Relation is an open totality evolving upon itself. That means that, thought of in this manner, it is the principle of unity that we subtract from this idea. In Relation the whole is not the finality of its parts: for multiplicity in totality is totally diversity. (1997:192)

Glissant is explaining that a totality can never be ahistorical. Any real totality must be opaque and therefore open to reformation or revolution. Like ecological philosopher Timothy Morton’s concept of subscendence (2017), in which the whole is less, not more, than the sum of its parts, relation for Glissant is a qualitative multiplicity that cannot be contained by unity. The end of Maxwell’s The Evening is a moment in which whiteness becomes opaque. Where previously whiteness was an unidentifiable neutral condition for some humans, here the spectators can see whiteness in actuality—a ubiquitous haze—highlighted and disembodied, made visible as a prelude to extinction.

Instead of mystifying whiteness behind the type, the haze makes whiteness opaque in relation to the acceleration of extinction events. Whiteness is a machine of extinction. This is not simply to say that white people cause extinction and are going extinct, but it is to say that whiteness as constructed by colonial humanism must be disembodied and made extinct so that new subjectivities of racial and ecological justice can evolve. It may be that whiteness as a historical invention must be transformed to secure survival. Living ecologically requires wide-scale dismantling of political collectivity and subjectivity. “As long as we calculate the future as one of sustaining, maintaining, adapting and rendering ourselves viable, the future will differ only in degree; this would mean of course that there will be no future for us other than an eventual, barely lived petering out” (Colebrook Reference Colebrook2014:58). This is why “sustainability” is such a problematic term. Sustainability too often props up the violent systems of colonial extraction that cause global warming in the first place. Avoiding extinction means redrawing the limits of the actual and the possible. A future theatre without whiteness as we know it would require an irreducibly political magic. What seems like magic is only a new science of possibility.

This is not simply to say that white people cause extinction and are going extinct, but it is to say that whiteness as constructed by colonial humanism must be disembodied and made extinct so that new subjectivities of racial and ecological justice can evolve.

Enchantment is not the same as mystification. One is the ordinary magic of all that exists existing for its own sake, the other an insidious con. Mystification blurs the simple facts of the shared world to prevent us from changing it. (Boyer Reference Boyer2019:41)

Maxwell’s haze is not a mystification of racist humanity but rather the enchanting opacity of ecology represented as an extinction not of white people but of the specific historical category of whiteness that bears a disproportionately large share of responsibility for planetary harm. The end of The Evening is the deconstruction of Maxwell’s world of types who happen to be white and their replacement with a world in which they are included in ways so new as to be opaque. Just in time, or too late, for a world that requires deep adaptation if the suffering caused by climate change is to be reduced, and if we want to materialize the conditions for collective joy.

Literally Still

My literal approach to performance is essentially one that includes the outside world. If this approach is to have any potency in a challenging if not desperate political situation the work will need to offer a convincingly usable system. A return to Churchill signals how ecological literalism in the theatre might develop. The last two catastrophic monologs in Escaped Alone represent fire and hunger. Later, back in the garden with her friends, the lights dim on three of the women and Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett is made prominent to share her inner thoughts. She is not standing in the electrified frame of the catastrophic present, and nor is she in the politely public friendly conversation of the garden. At earlier moments in the show, when each of the other three women are individually in the spotlight to share an internal monolog, they tell stories. One divulges secrets of a violent dinner party, another of a fear of cats, and the last of depression. Mrs. Jarrett/Linda Bassett however repeats the words “terrible rage” 25 times (Churchill Reference Churchill2016:42). The extended repetition is an energetic moment full of irreducible affect. Perhaps this is Linda Bassett/Mrs. Jarrett acknowledging that environmental collapse provokes terrible rage. Her rage is also an expression that the exclusionary narratives legible in neighborly conversation obscures the talk and action necessary for the political change required for ecological survival. Furthermore, the affective charge of her repeated rage is corporealized as resistant to any transcendent metaphor. Any meaning that seeks to escape materiality is potentially rendered obsolescent—no longer able to provide, through art, some kind of political reflection. Even narrative and metaphor need materiality. The literally ecological supersedes metaphorical meaning.

Ecological theorists too have used the literal to understand human behavior in relation to climate. Bruno Latour questioned whether we have “shifted from a symbolic and metaphoric definition of human action to a literal one? After all, this is just what is meant by the Anthropocene concept: everything that was symbolic is now to be taken literally. Cultures used to ‘shape the earth’ symbolically; now they do it for good” (2011:11). Latour argues that even cultural human action has unintended physical consequences that threaten epistemology, in a kind of inverse historical materialism. My critical approach of ecological literalism therefore accounts for the compositional interdependence of metaphor, story, and ideology—which then become the reality of the world…until it changes again. Extreme weather events and the cinema of catastrophe point out the two-way relationship of culture and nature in which the normalized but violent material conditions of production are obfuscated by the spectacular mediation of harm. The scale and complexity of ecology is a challenge to our epistemologies. As Colebrook explains: “We are at once thrown into a situation of urgent interconnectedness, aware that the smallest events contribute to global mutations, at the same time as we come up against a complex multiplicity of diverging forces and timelines that exceed any manageable point of view” (2014:11). Ecological literalism throws into relief one of the most difficult questions of the Anthropocene: How is it that some humans are responsible for causing climate change while no humans are able to alleviate it?

When I think literally about climate change, I note the invention of thousands of possible solutions. Yet nothing on a scale appropriate to the magnitude of the problem is being done. I also see productions of ecotheatre that, through greenwashing, reduce the complexity of the issues into a naively personal domain of lifestyle consumption. Too often ecological thinking refuses to encounter the difficult questions that underpin the continuation of life on earth. Facile ecological discourse wants to remind humans that we are a part of nature. If humans are a part of nature, anthropogenic climate change and the resulting loss of biodiversity is a part of nature too. Understood this way, the concepts themselves are part of the problem. The way ecological relationships between organisms and their environments are understood must change. Why would we sustain something that causes suffering? As Colebrook puts it: “By asking how we will survive into the future, by anticipating an end unless we adapt, we repress the question of whether the survival of what has come to be known as life is something we should continue to admit as the only acceptable option” (2014:202). What is poignant about the two case studies I discuss is that they do not go so far as to ask how we will survive. Instead they are occasions to consider how we are dying, and what practices of living might go extinct so that other forms of life can survive.

In these two plays—Churchill’s Escaped Alone and Richard Maxwell’s The Evening—hybrid character/actors articulate the reality and horror of ecological violence while also accepting their inability to fix it. But neither playwright argues for inaction. Not knowing whether burning fewer fossil fuels will stop rising temperatures, because it is already too late, does not mean we should not live in a solar economy, with breathable air in cities. We can admit a lack of control at the same time as we take responsibility for our actions. Doing so would require giving up the fantasy of a certain kind of white human exceptionalism that instrumentalizes every literal piece of matter into a symbol for a transcendental zone of permanence. New understandings of political and ecological reality, especially understandings that include a healthy dose of theatricality, might be the material preconditions for systemic change at a scale equal to the immensity of the problem. Practicing literalism, as Una Chaudhuri advocates, is about not getting in the way of the actual material and its agency in the construction of the immaterial. Weather makes its way inside. The potent affective charge of the literally ecological is a new set of terms of responsibility for life.

What I am describing is a drift into opacity, to resist mastery while speaking accurately, and even, as Julietta Singh has explained, “exile ourselves from feeling comfortable at home” (2018:10). As so many have already been forced from their homes, it is not the building of the same old house that fixes the problem, but rather the reimagination of what a house might be.