Introduction

Cities are at the forefront of formulating policies that aim to improve the precarious situation of irregular migrants.Footnote 1 These urban policies are mostly discussed under the label of ‘sanctuary cities’, though sanctuary cities are a particularity of US federalism because US local governments are not obliged to cooperate with federal immigration authorities (see, for example, Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien Reference Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien2019, Mancina Reference Mancina2016). Yet, the urgency for cities to provide a sanctuary for irregular migrants resonates with cities worldwide (see, for example, Bauder Reference Bauder2017; Darling and Bauder Reference Darling and Bauder2019). This letter geographically expands sanctuary city research by comparatively examining how European cities address the precarious situation of irregular migrants. So far, these urban policies and practices in Europe have merely been examined through case studies of different European cities (see, for example, Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020; Kaufmann and Strebel Reference Kaufmann and Strebel2020) or through policy reports that compare selective cities (see, for example, Delvino Reference Delvino2017). We present a systematic collection and descriptive analysis of urban policy in support of irregular migrants in Europe's 95 largest cities.Footnote 2

Irregular migrants tend to live in dense urban settings because of the higher likelihood of finding jobs and suitable accommodation, better access to relational, ethnic, social or cultural networks, and greater anonymity (Spencer Reference Spencer, Spencer and Triandafyllidou2020). Therefore, there is an immediacy for city governments to support and protect irregular migrants (Bauder Reference Bauder2017; de Graauw Reference De Graauw2014; Varsanyi Reference Varsanyi2006), and the city can become ‘a space that challenges the exclusion perpetrated at the level of the nation-state’ (Darling and Bauder Reference Darling and Bauder2019, 4). In practice, cities employ a variety of urban policies and practices that support irregular migrants (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2019). By doing so, cities challenge the national state as the only regulatory body over immigration and citizenship policy.

We define irregular migrants as migrants who either never obtained any sort of residence status or had a status but later fell out of that status or allowed it to lapse. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN OHCHR 2014) estimates that 30–40 million migrants live in an irregular situation worldwide. A total of 12 million live in the US (Gonzalez O'Brien, Collingwood and El-Khatib Reference Gonzalez O'Brien, Collingwood and El-Khatib2019) and 2.9–3.8 million live in Europe (Pew Research Center 2019).

In the European context, cities are not only seeking solutions for migrants that never obtained a residence status; rather, they are mostly confronted with migrants whose asylum applications were denied but who nevertheless stayed (Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020). For example, following the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015/16, European countries refused the applications of more than a million asylum seekers, but their rate of return was well below 50 per cent (Spencer and Delvino Reference Spencer and Delvino2019). Some European cities directly oppose the increasingly restrictive national policies towards irregular migrants and rejected asylum seekers (Garcés-Mascareñas and Gebhardt Reference Garcés-Mascareñas and Gebhardt2020; Mayer Reference Mayer2018).Footnote 3

This letter provides a descriptive analysis of policies in support of irregular migrants in European cities based on an extensive data-collection and data-categorization process. The process consists of three steps: initial data collection, standardization and expert validation. We then analyse the data collected using a mixed-methods approach, including qualitative case knowledge and logistic regressions. We offer an inductively built policy categorization that distinguishes between urban policies that award a (more) secure status and policies that facilitate access to city services. We then propose some tentative explanations to make sense of urban policies in support of irregular migrants in Europe.

Different types of urban policies in support of irregular immigrants

Policies in support of irregular migrants are often mobilized by activating the normative concepts of jus domicili (membership upon residence) and urban citizenship. Both concepts view the city as an alternative locus of membership, regardless of residence status (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2003; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2019; Varsanyi Reference Varsanyi2006).

Few categorizations in the literature elaborate on the diverse urban policies in support of irregular migrants. Kaufmann (Reference Kaufmann2019) distinguishes between regularization, sanctuary cities and local bureaucratic membership. Regularization programmes confer national residence status on irregular migrants. Within these programmes, cities can make use of their implementation discretion, as they sometimes have a role in defining or evaluating regularization criteria. Sanctuary cities are cities that have passed a resolution or ordinance expressly forbidding city or local law enforcement officials from inquiring about immigration status and/or cooperating with national immigration enforcement authorities (Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien Reference Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien2019). In this definition, sanctuary cities are a product of US federalism: given that immigration control is the responsibility of the US federal government, cities cannot be compelled to cooperate with immigration enforcement. Local bureaucratic membership aims to facilitate irregular migrants' access to city services (de Graauw Reference De Graauw2014). Buckel (Reference Buckel, Frey and Koch2011) further distinguishes between access to city services based on parallel structures, that is, services specifically developed for irregular migrants, often in collaboration with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and regular structures that ensure access to city services for irregular migrants in the same way other residents access them.

These different policies are not mutually exclusive. They often complement each other, but they can also be incoherent and have contradictory directions and effects (Bauder Reference Bauder2017). Thus, cities often formulate regimes of policies and practices that seek to make residence status irrelevant in most interactions between residents and city employees (Mancina Reference Mancina2016). We attempt to capture this diversity of policies in support of irregular migrants, yet we are also trying to compare them; thus, we are creating simplifications that are a necessary step of concept building (Goertz Reference Goertz2006).

Research design

We survey urban policies in support of irregular migrants in all 95 European cities that have more than 350,000 inhabitants. This is a snapshot analysis, as the data were gathered from 2018 to 2020. Data collection represented an intense endeavour. Comprehensive data on urban policy are often extremely difficult and resource-intensive to obtain and maintain (Sumner, Farris and Holman Reference Sumner, Farris and Holman2020).

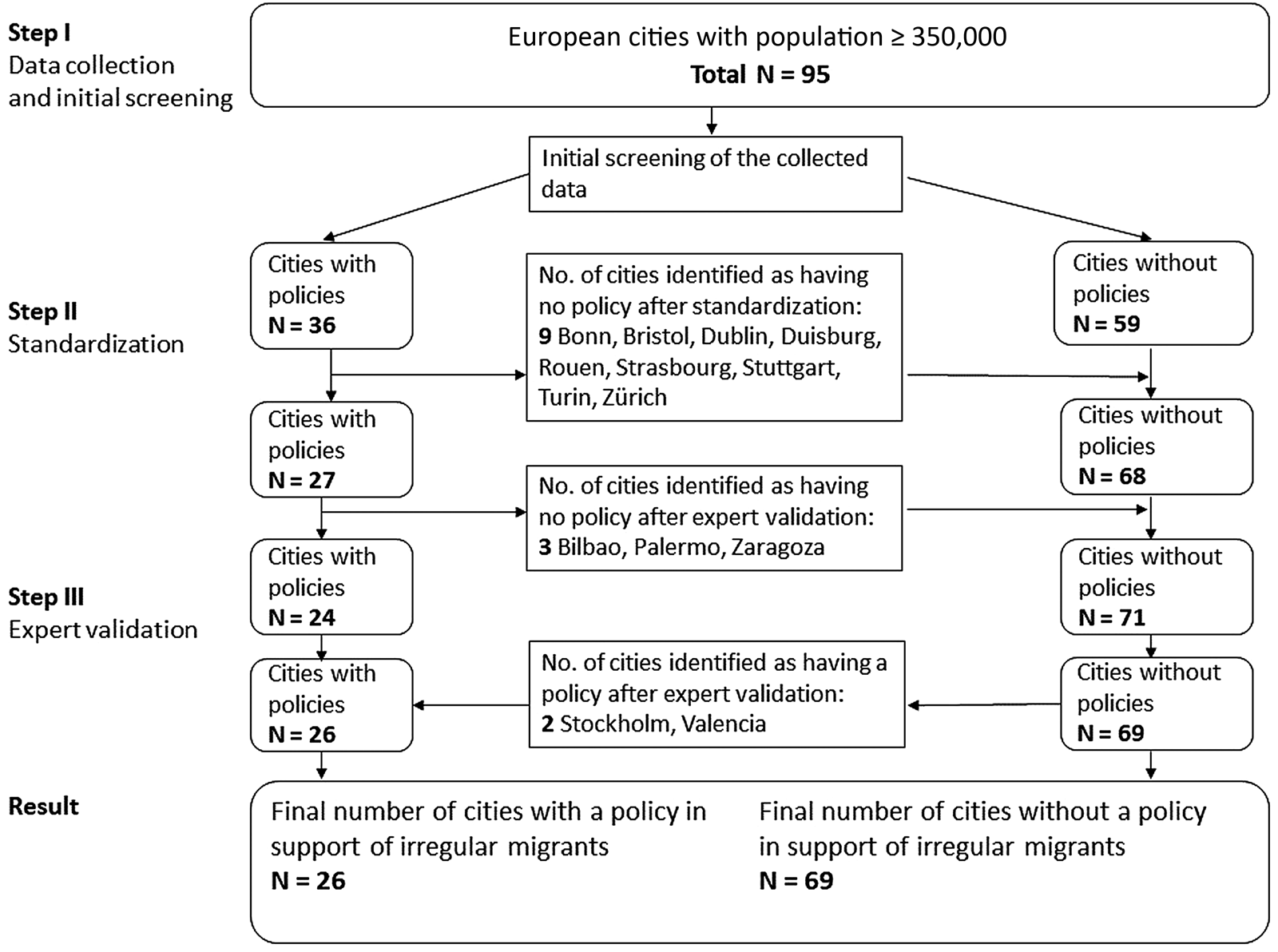

The data-collection and data-categorization process consisted of three steps (see Figure 1). First, we reviewed available academic articles or (policy) reports before starting an open Internet search using a catalogue of search terms in both English and the respective national language(s) (see Online Appendix A.1). As we are interested in how cities are openly active in a policy field that is under the formal authority of national states, we only include policies officially mentioned and implemented by city governments that deliberately target irregular migrants. We therefore did not include national policies implemented by cities, not-yet-implemented policies or symbolic declarations. We wrote short city profiles for each city in which we found a policy (see Online Appendix A.3). Second, we categorized these policies. This standardizing exercise was conducted very carefully through multiple rounds of discussions between the participating researchers to preserve place-based policy diversity, while still allowing for the comparison of policies. We also conducted additional investigations into specific cases. Third, 15 experts helped us validate the information in our city profiles. We gave the city profiles to the experts and asked them: (1) whether the city profile descriptions were correct; and (2) whether they were aware of other policies in this or any other city. We ensured that each city profile was checked by at least one expert. We selected experts that published about irregular migration in the specific cities in question or that worked in the city administration (see Table A.1.1 in the Online Appendix). This three-step method constitutes a collaborative process of knowledge generation that enhances the rigour of the collected and categorized data.

Fig. 1. Data-collection and data-categorization process.

We analysed the collected data using a mixed-methods approach, including qualitative case knowledge and logistic regressions. We estimated logistic regressions using cluster robust standard errors (Williams Reference Williams2000) to control for the importance of national legal immigration frameworks. The regression models include the independent variables of population, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in the metropolitan region, share of migrant population and political ideology of the mayor (see Online Appendix A.2). We interpret the outcomes of the logistic regressions together with qualitative case knowledge given the observed place-specific idiosyncrasies as well as the data limitations of central explanatory factors.

Findings: status and service

We distinguish between policies that aim to award a (more) secure status to irregular migrants and policies that facilitate access to city services. The status policy category is conceptually related to the local implementation of regularization programmes and sanctuary cities, and the service category is conceptually related to local bureaucratic membership.

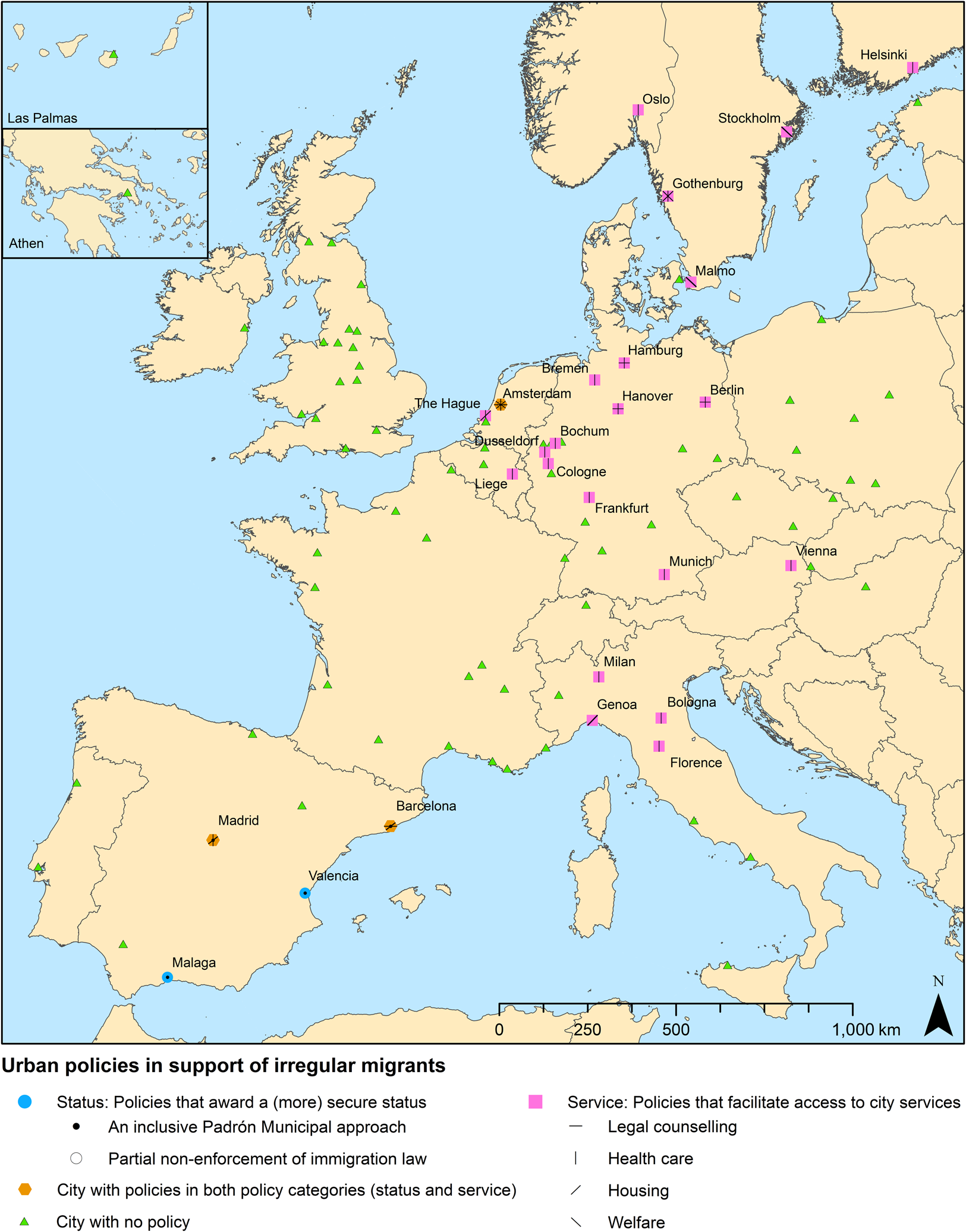

Out of the 95 cities, five (5.3 per cent) formulate policies that award irregular migrants with a (more) secure status, 24 (25.3 per cent) formulate policies that facilitate access to city services and 69 (72.6 per cent) formulate neither (see Table 1). Amsterdam, Barcelona and Madrid are the only cities that formulate policies in both policy categories. Additionally, Amsterdam aims to facilitate access to all four types of city services, which highlights the encompassing nature of its ‘24-Hour Reception for Undocumented Migrants’ plan (see City of Amsterdam 2018). Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution of these policies.

Table 1. Overview of urban policies in support of irregular migrants

Fig. 2. Map of policies in support of irregular migrants in European cities.

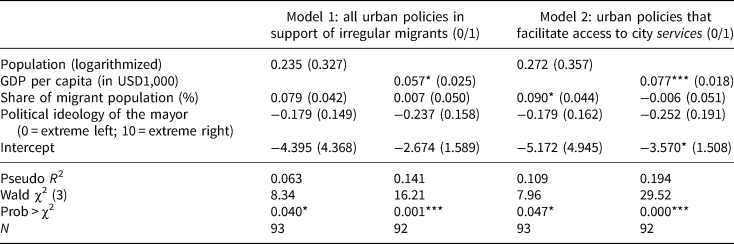

We ran two regression models: Model 1 includes all urban policies in support of irregular migrants as the dependent variable; and Model 2 only includes service policies as the dependent variable (see Table 2). We split both models into two sub-models because of multicollinearity problems between the variables of population and GDP per capita. We refrain from estimating a model of status policies because the variance is too low and extremely clustered in Spanish cities. The qualitative case knowledge is better suited to describe and interpret these five cases than a logistic regression.

Table 2. Results of the logistic regressions

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The logistic regressions reveal a positive statistical association at the 95 per cent confidence interval between GDP per capita and all policies, as well as between GDP per capita and service policies. It seems that affluent cities have more resources at their disposal and more capacity to formulate policies in support of irregular migrants. There are no other statistical associations at the 95 per cent confidence interval. The association between the share of migrant population and service policies vanishes in the model that includes GDP per capita. We discuss the null findings in the Online Appendix (see section A.2). We will examine these findings by relying on the gathered qualitative case knowledge.

Status: policies that award a (more) secure status

We found two types of policies that fall into our category of awarding a (more) secure status: an inclusive approach to entry into the Spanish Padrón Municipal registry; and partial non-enforcement of immigration law in Amsterdam. These policies rest upon the policy-making discretion that the national legal immigration frameworks grant to cities.

Four Spanish cities openly formulate an inclusive approach to registration in the Padrón Municipal, an administrative municipal record in Spain. Spanish law obliges everyone residing in Spain to register in the Padrón Municipal, without excluding irregular migrants.Footnote 4 Registration makes a person eligible for public services, and it can substitute for an identity card when, for example, opening a bank account or issuing a library card. In addition, the Padrón Municipal becomes important as a proof of residence and social integration within Spain's permanent regularization mechanism (arraigo). Thus, the Padrón Municipal simplifies access to city services in the short term and facilitates regularization in the long term.

Spanish municipalities enjoy very high administrative discretion regarding the documents that they require for registration, as well as when assessing irregular migrants' social integration as part of the regularization process (Delvino Reference Delvino2017, 5–6; Moffette Reference Moffette2018). For example, Barcelona and Madrid accept affidavits from social workers and religious figures to confirm a person's identity (Moffette Reference Moffette2018, 140). Moreover, Barcelona and Valencia encourage residents to register even if they do not have an official address (Delvino Reference Delvino2017, 32). In contrast, other Spanish municipalities obstruct the registration of irregular migrants by requiring minimum living standards or even residence permits (Delvino Reference Delvino2017, 32; Moffette Reference Moffette2018, 140). We only include Spanish cities in our survey if we found official policies that facilitate an inclusive approach to entry into the Padrón Municipal.

Amsterdam developed the ‘free in, free out’ policy, which guarantees irregular migrants the right to freely enter and leave a police station to report a crime, whether as victims or witnesses. The police of Amsterdam-Zuidoost piloted this programme in collaboration with local migrant support organizations and with the consent of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security (Delvino Reference Delvino2017, 35–6; Timmerman, Leerkes and Staring Reference Timmerman, Leerkes and Staring2019). After the successful test in Amsterdam, other Dutch cities can now also implement this practice, as it was formally introduced as national policy in 2015. It ‘has been recognized by various migrant and human rights observers as a European “best practice” in the area of safe reporting for irregular migrant victims of crime’ (Timmerman, Leerkes and Staring Reference Timmerman, Leerkes and Staring2019, 18). This policy therefore shares some similarities with sanctuary cities; however, it only guarantees the non-enforcement of immigration law in specific circumstances (that is, when reporting crime).

Service: policies that facilitate access to city services

Policies that facilitate irregular migrants' access to city services resemble what Els de Graauw (Reference De Graauw2014) calls ‘local bureaucratic membership’. Cities try to ensure basic services for all people in precarious situations by making residence status irrelevant when accessing city services (Buckel Reference Buckel, Frey and Koch2011; Spencer Reference Spencer, Spencer and Triandafyllidou2020).

Legal counselling is one such service that is available in many cities. These services are crucial given that the irregular migrants' precarious situation stems from national immigration legislation. City governments invest in legal counselling to inform irregular migrants about pathways out of irregularity. Legal counselling is mostly done by NGOs themselves through so-called ‘parallel structures’ because irregular migrants may perceive them as being more trustworthy than city governments. Our survey only incorporates examples of cities that officially fund these services.

Ensuring access to health care is the most frequent policy in our survey (n = 20). There is a cluster of German cities (nine out of 20 cases) that set up clearing offices to assess whether it is possible to refer patients to the public health-care system or that set up local medical consultation centres to provide anonymous medical consultation and basic health services (Delvino Reference Delvino2017, 26). These health-care policies specifically target irregular migrants without health insurance. Helsinki provides an interesting case, as the city provides free health care for all irregular migrants that live in the city, and it developed an internationally recognized best-practice protocol (PICUM 2017, 17).

Six cities formulate policies that facilitate access to housing. Gothenburg funds several shelters that are explicitly open to irregular migrants. Amsterdam and Madrid financially support NGOs that mediate between tenants who are irregular migrants and landlords. However, these housing programmes have also become conflictual because the national policies of many European states aim to ‘encourage’ the ‘voluntary return’ of rejected asylum seekers by deteriorating their living conditions. The city of Amsterdam, for example, explicitly and openly challenges this national strategy, and emphasizes the city's responsibly to guarantee basic needs (including housing) for all people who live in the city (Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020, 123–4).

Irregular migrants can access welfare provisions in four cities. Most notably, all large Swedish cities offer welfare for families that have children and who are in an irregular situation. Swedish cities do not have to pay benefits to people without a residence status, but they can do so if they wish (Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020). Amsterdam provides monthly allowances to irregular migrants who lack sufficient funds. Again, these welfare provisions lead to conflicts with the Dutch government (Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020, 122–3).

Conclusion

Out of the 95 largest European cities, only about 27 per cent formulate policies in support of irregular migrants. Around 5 per cent of these cities formulate policies that award a (more) secure status to irregular migrants, and around 24 per cent formulate policies that facilitate access to city services. These numbers are rather low compared with the US, where more than 100 cities have passed sanctuary laws (Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien Reference Collingwood and Gonzalez O'Brien2019). The main reason for this transatlantic difference lies in the different institutional settings of European national states. It is also necessary to interpret this low number of policies in European cities cautiously because many urban policies in support of irregular migrants are often provided through a web of parallel structures via civil society organizations (Buckel Reference Buckel, Frey and Koch2011; Mayer Reference Mayer2018; Spencer Reference Spencer, Spencer and Triandafyllidou2020). Cities may also choose to strategically engage in low-visibility forms of support for irregular migrants in order to prevent conflicts with national governments (Delvino Reference Delvino2017; Spencer Reference Spencer, Spencer and Triandafyllidou2020).

This letter provides an empirical contribution to the study of irregular migration and sanctuary cities and a methodological contribution to the study of comparative urban policy. Empirically, we provide a descriptive overview of, as well as a conceptual distinction between, urban policies that aim to award a (more) secure status to irregular migrants and urban policies that facilitate access to city services. Status policies are prone to provoking conflicts with the national level because they contest the primacy of the nation state in immigration and citizenship policy making (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2019). Few cities implement status policies, and those that do take advantage of their policy-making discretion. National migration laws set the scope of discretion for status policies. Within this scope, discretion allows urban policy makers to formulate bottom-up policy responses even though they might be decoupled from national (migration) policies (Sager, Rüefli and Thomann Reference Sager, Rüefli and Thomann2019). Similar to actor-centred institutionalism (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1997), urban policy making in support of irregular migrants depends on purposive actors that are constrained but not determined by national migration laws.

Service-oriented policies are more pragmatic measures (de Graauw Reference De Graauw2014), but they can also lead to intergovernmental conflicts as European states try to harshen the lives of irregular migrants in order to ‘incentivize’ their return (Ataç, Schütze and Reitter Reference Ataç, Schütze and Reitter2020). Cities have more autonomy when establishing service policies than when establishing status policies. The regression results show that GDP per capita correlates with service policies, suggesting that more affluent cities have more resources for funding service policies. Thus, cities have policy-making autonomy in service policies, yet they are costly and also controversial.

Methodologically, we demonstrate that our data-collection and data-categorization process produces meaningful and reliable data about comparative urban policy. We developed this extensive and collaborative process because urban policies in support of irregular migrants are products of complex policy-formulation processes in which institutional opportunities, political agency and the resources of local actors result in often rather idiosyncratic policies (Kaufmann and Sidney Reference Kaufmann and Sidney2020). Studying comparative urban policy is a balancing act that requires paying close attention to path-dependent and place-specific idiosyncrasies, while searching for and identifying commonalties. We believe that by engaging local experts and by relying on a mixed-methods analysis, we have developed a rigid process for conducting large-scale, comparative urban policy analysis.

This letter advances sanctuary city research outside of the US. Our analysis could be improved with better data about irregular migrants, yet the absence of reliable (local) data on the presence of irregular migrants is a key limitation for studies on irregular migration (Spencer and Delvino Reference Spencer and Delvino2019). Future analyses could benefit from more fine-grained city-level data about relevant urban policy-making actors. Studies on local legislative bodies might be interesting, as they can play a key role in advancing urban policies in support of irregular migrants (for example, in the case of Zürich, Kaufmann and Strebel Reference Kaufmann and Strebel2020). Additionally, immigrant-serving NGOs play a crucial role in pushing policy making in this field (see, for example, Kaufmann and Strebel Reference Kaufmann and Strebel2020; Mayer Reference Mayer2018, Spencer Reference Spencer, Spencer and Triandafyllidou2020); however, there is no reliable comparative city-level data that represent this activity. Case studies could accompany our comparative research to account for in-depth and path-dependent policy-formulation processes, as we only compare these policies in space, not in time. Despite these limitations, we show that a rigorous data-collection process and careful mixed-methods research can provide meaningful comparative urban policy findings in an important and contested policy field.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000326

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QBJ3JS

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editors of the British Journal of Political Science and the reviewers for their suggestions that helped to improve this letter. A cornerstone of this analysis was the expert reviews of our city profiles. We want to express our immense gratitude to the 15 experts for sharing their valuable knowledge and time with us. We are also indebted to Stefan Wittwer, who offered valuable advice several times, and to Sophie Hauller for her support in creating and designing the map in Figure 2. This letter also benefited from the comments of Abigail Fisher Williamson, Claire Galesne and colleagues from the Comparative Urban Politics group of the American Political Science Association.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.