Introduction

The history of the Bata company is generally perceived through the lens of its spectacular industrial growth.Footnote 1 Its hometown, Zlín, has largely been shaped and developed by the firm. Within a few years of the company being founded, it had become an emblematic industrial city with a remarkably sophisticated social welfare system. Later, in the 1930s, the firm engaged in an ambitious expansion through the establishment of more than thirty company towns, inspired by the Zlín model, in no less than sixteen countries in Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Built from scratch, mostly in isolated areas, these settlements were intended to become part of a global network of new satellite cities, all maintaining the same common standards and principles.

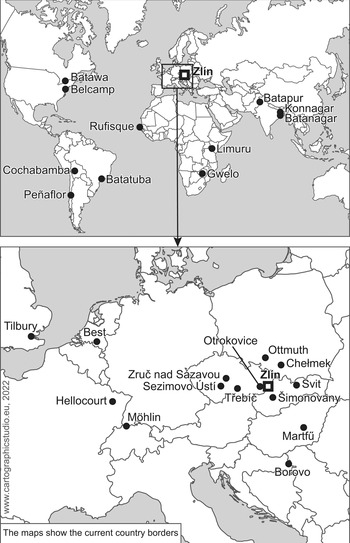

Currently, there is renewed interest in these company towns. The seemingly illogical advance of one small company from a Moravian provincial town to one of the largest shoe producers in the world (Figure 1) has attracted the attention of various organizations and individuals.Footnote 2 Interest in Bata waned in the decades after World War II, as the company assets were nationalized in the Communist Bloc. Having gradually abandoned its social welfare system in the West, Bata appeared as just another firm in the footwear industry. However, in the last three decades, since the regime change in Central and Eastern Europe, the history of the firm and its company towns has once again received significant attention. Today, almost 1,700 books, articles, student theses, and other works have been published on the history of Bata.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Bata company towns around the world.

The transnational dimension of Bata's history remains neglected, however, as most studies have focused on Zlín or on specific European settlements. There is a need, therefore, to bridge a historiographical gap by investigating Bata's transnational activity in other geographical areas. A partial explanation of this blind spot can be found in the enterprise's extreme decentralization after World War II, when it operated with intentionally limited headquarters in London and, later, in Toronto. With such a structure, and with the vast majority of the documents essential for understanding the global history of the company dispersed between different company archives – from North America to Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe – it is an arduous task to cover and research all the relevant archives and institutions.

Two recent studies with a primary focus on urbanism have opened up new perspectives on Bata's transnational history by comparing its settlements in different parts of the world.Footnote 4 While they stress the isomorphic power of the firm, which underpinned the development of common urban planning and principles of social organization across continents, they also provide clues as to how local settlements have deviated from the original plans. Moreover, evolutions of the model itself have been highlighted: Victor Muñoz Sanz has shown how Bata's urban design moved away from the Garden City planning principles before re-adopting them later on.Footnote 5 The author also argues that the company tempered its transnational vision, showing “an intention to ground the projects in their local social and cultural contexts”.Footnote 6

As we shall see, deviation from the original Zlín model went beyond the strict domain of urban planning to encompass human resources policies, industrial relations, work organization, and community life. In this article, we ask why Bata company towns assumed different forms despite the global project to export a unique model, and we seek to identify the logic underlying these diverging patterns. In this regard, geographical constraints, economic conditions, and political actors are obvious local factors that need to be considered. Less obvious are the complex interplays between the Bata welfare policies and those that were developed simultaneously by the relevant nation states, and which could potentially limit the organizational isomorphism of the firm. As evidenced by our study, Bata company towns never fully constituted “a state within a state”.Footnote 7 This finding suggests an understanding of how the firm could – or could not – supersede, challenge, or subvert the nation states. More dynamically, we seek to identify how the rise and fall of Bata's welfare activity in its company towns can be related to the evolution of universal social benefits, labour legislation, and national welfare regimes.

The global history of Bata company towns offers us an opportunity to link two separate literatures. Following recent studies on the circulation of models and practices,Footnote 8 our analysis underlines the problematic character of institutional transfers within multinational companies and the uncertainty surrounding the adaptation of their policies and practices to local conditions. It thereby contributes to the study of globalization of business practices in the twentieth century, with a special comparative focus on the different national contexts. The second body of literature relates to the historiography of company towns, welfare capitalism, and industrial paternalism.Footnote 9 The central question of how welfare capitalist practices have been more or less dialectically related to the development of the state has mostly been addressed through national case studies, in particular in North America. With its international dimension, the case of Bata company towns offers new insights into how national histories have affected the dynamics of welfare capitalism.

Our perspective is in line with recent discussions on transnational history. We argue for the need to avoid the trap of “methodological nationalism” without neglecting the local isomorphisms, especially those resulting from the activity of nation states.Footnote 10 We depict the history of Bata company towns paying attention to what happened within each nation state, but also between or beyond nation states. Our research thus draws upon a comparative-historical analysis of archival sources from different locations in the world. We conducted research at the state regional archive in Zlín, where the documents from before nationalization in 1945 are stored. We also worked with material from the factory archive in Batanagar in India, files and documents donated by the company to the University of Toronto, the company archives in Best, the Netherlands, and Möhlin, Switzerland, as well as the departmental archives in Saint Avold and Saint-Julien-lès-Metz in France. We also used published literature and autobiographical materials, such as employers’ memoirs and diaries.

Zlín: The Making of a Bata Social Welfare System

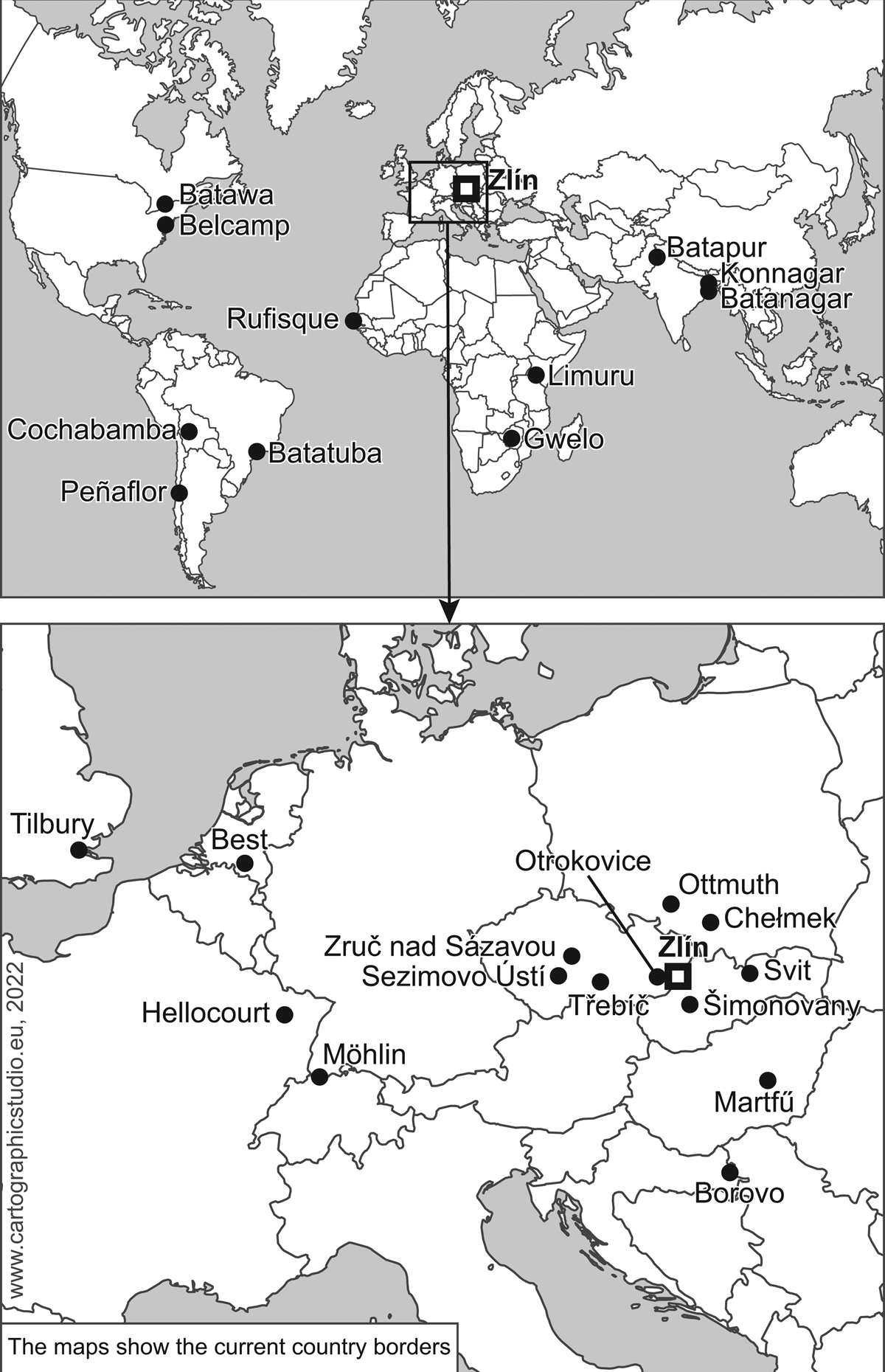

The Bata company was founded in 1894. At that time, Zlín, despite its long history and a certain manufacturing tradition,Footnote 11 was a small town on the periphery of the Czech lands and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The firm started to develop and expand significantly from the beginning of the twentieth century thanks to machine innovations, which were brought from Germany and the US, and a specific organizational structure implemented by the company founder, Tomáš Baťa. Nevertheless, after World War I, with the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the loss of its large internal market, the company struggled to find a market for its products. The firm introduced strategic restructuring, such as reducing product prices by half,Footnote 12 which brought in much-needed capital and further rationalized production based on American models (Taylorism, Fordism). In addition, the favourable market development after the early 1920s contributed to the enterprise's re-expansion.Footnote 13 In this period, the importance of Zlín in the overall Czechoslovak economy grew with every new year. While Zlín was just a modest town of 2,976 inhabitants in the early twentieth century, its population grew more than tenfold in just three decades, and, in 1938, 36,243 lived in the city, putting it among the ten largest urban areas in the country, and one of the most important industrial centres (Figure 2).Footnote 14 In the 1930s, the firm became the largest taxpayer in the state and covered 90 per cent of Czechoslovak shoe exports; indeed, mainly because of this enterprise, by 1935, Czechoslovakia had become the largest exporter of leather footwear in the world and the second-largest exporter of rubber footwear.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Postcard with a view of Zlín in the 1930s. Bata houses for employees with the factory in the background.

Bata Information Centre. Tomas Bata University, Zlín, Czech Republic.

The rapid economic growth of the Bata company was fostered by a very elaborate system, combining an advanced method of organizing work and a specific social order. The production process was rationalized in order to reduce losses of raw materials, time, and resources.Footnote 16 Workshops were equipped with newly invented or upgraded machines, and in the 1920s conveyor belts were installed. In addition, to motivate the workers, production units were defined as autonomous cost centres and managed a specific profit-sharing system.Footnote 17 Tomáš Baťa, the company founder, was not a theorist and did not develop an extensive and elaborate system of ideas. Rather, he was a practitioner.Footnote 18 Following the first strikes in his Zlín factory, he demanded the exclusion of politics in the workplace, although the workers or management were not forbidden from taking part in political life outside of the factory. Nevertheless, the company's founder tried to avoid political involvement and attachment to ideologies, even in the period when he was the mayor of Zlín (1923–1932). By contrast, in the second half of the 1930s, his successor, Jan Antonín Baťa, would express admiration for the futuristic aspirations of the Mussolini regime in Italy.Footnote 19 While the aforementioned measures were introduced in production, Zlín, simultaneously, continued to evolve. The roots of this transformation can be found in Tomáš Baťa's fascination with America and its models.Footnote 20 The influence of Fordism and Taylorism is visible in his rhetoric, expressed in the articles that he wrote for publication in the factory newsletter, or which were published by other authors in the same media. Ford's idea of a city shaped by a private entrepreneurial initiative led to a transformation in all aspects of the city: economic; social; political; and technical.Footnote 21 Motivated by this, the Bata company took over many responsibilities that were usually within the state's jurisdiction or that of religious institutions, such as building hospitals, schools, community houses, cultural facilities, sports grounds, and swimming pools. From 1924 onwards, the company began its support of the Bata Sports Club, for which it built sporting facilities. In addition, the company founded a social and health department and, in 1928, it set up a Bata Support Fund, aimed at organizing and financing broader social activities. By means of these policies and institutions, the Bata company supplanted and enhanced the flawed state social security system of the day, making Zlín a company town typical of welfare capitalism, i.e. a place where capitalists could control the social protection system at their discretion.

Beyond American models, Bata was likely influenced by the Garden City movement, mainly from Germany. Most of the characteristics of those cities can be found in the Bata model. Even Tomáš Baťa's thoughts on the need for individual housingFootnote 22 were reminiscent of the rhetoric of the Deutsche Gartenstadtgesellschaft (German Garden City Association).Footnote 23 This model was the foundation for the building of individual tenement houses containing one, two, or four flats, instead of the collective workers’ barracks associated with the unhealthy and detrimental life of the urban poor.Footnote 24 Therefore, in Zlín, Bata built a specific social system of its own, drawing on business and social models circulating in Europe and across the Atlantic. The company founder's paternalist ideas were similar to Karl Schmidt-Hellerau's vision of building Hellerau as an instrument of social reform that would enhance the lives of working families.Footnote 25 Nevertheless, while its inspiration can be viewed as a parallel with some other paternalist capitalists, from Pulman to Krupp's Margaretenhohe, Cadbury's Bournville, or the Lever brothers’ Port Sunlight,Footnote 26 what distinguished Bata from other models was its scope and the intention to spread the Zlín model globally. This Zlín model rested upon five pillars: urbanism applied to the industrial city; the employer's moral values; industrial relations geared towards social harmony; and sport and social events organized by the company.

On this basis, a specific difference can be observed between Bata and the corporate policies that developed the company towns systems that preceded it. For example, Bata may have been inspired by American models, but they were mainly realized on a nation level. During the 1930s, it would transpire that the model of a company town in a national context (which was not specific solely to American, but also to other companies that founded similar settlements) was not economically viable due to a number of unfavourable circumstances in local, national, and supranational contexts (depletion of natural resources, increased state intervention in the area of working conditions and workers’ rights, and the Great Depression). By contrast, at that time, Bata was embarking on his project of founding numerous company towns abroad. In this regard, it is essential to highlight two facts directly related to the business vision of Tomáš and Jan A. Baťa. First, over time, they recognized Czechoslovakia's unfavourable structural predispositions for the expansion of their own company (primarily the continental character of the country, the lack of natural resources, and no access to large markets due to the protectionist policies introduced in response to the Great Depression). Second, they tried to internationalize their model of company towns, although this was unnecessary (they could have chosen to establish factories without building settlements and transferring social institutions).

Urbanism and the Search for an Ideal Industrial City

Bata invested substantial resources in improving the living conditions of its employed workforce. After 1924, the Company had a construction department, which built standardized, functional concrete and brick factory buildings with large windows to let in the light.Footnote 27 Some of the best Czech architects were recruited, such as František L. Gahura, Vladimír Karfík, Antonín Vítek, and others. Under a concept developed by F.L. Gahura, the transformation of Zlín into a garden city began. Gahura and Tomáš Baťa were heavily influenced and inspired by a series of ideas developed from the earlier utopian urban concepts of Ebenezer Howard and Frank Lloyd Wright for the creation of an ideal (garden) city. The influence of Ebenezer Howard's concept of an ideal industrial city for 32,000 people can be seen in Gahura's plan for an ideal industrial town for 10,000 people.Footnote 28 In later phases, the Bata architects and managers were also inspired by Le Corbusier, who began cooperation with Bata and, in 1935, even came to Zlín. However, Jan A. Baťa and Le Corbusier's collaboration achieved little more than attracting media attention, which the company's marketing department used widely.Footnote 29

The standard factory building was based on a 6.15 × 6.15-metre spatial module, with a reinforced concrete frame, brick lining, and large swathes of glazing. Later, this model was also used for hospital buildings, department stores, schools, dormitories, and other public buildings. In addition to factory premises, residential buildings were constructed for employees, from one- and two-flat houses for senior workers and administrative staff to four-flat dwellings for workers.Footnote 30 In line with Tomáš Baťa's ideals, these houses had their own gardens and were not fenced off from other homes and neighbourhoods. The flats averaged in size from fifty to seventy m2. For the interwar period, the workers’ accommodation standards were very advanced with running water, electricity, sewerage, and other benefits. All the buildings had two storeys and similar interior layouts. The ground floor consisted of an anteroom, a dining room, a kitchen, and a bathroom, with one or two bedrooms on the first floor, depending on the house's size. The rent for these flats was heavily subsidized and usually accounted for only a small portion of the employees’ salaries.Footnote 31 As a result of Bata's efforts, more than 2200 houses were built in Zlín. The firm even organized a competition in 1935 to attract architects from around the world to find the most suitable model for building the houses. Aside from accommodation units, as has already been mentioned, public buildings were constructed, and the company shaped Zlín to satisfy both its needs and ideology. This resulted in the building of new residential neighbourhoods next to the old historic town and the establishment of an extensive factory complex consisting of more than seventy buildings. Zlín, which had originally developed organically, was now shaped after the concept of an ideal industrial town.Footnote 32

Moral Values and the Quest for the Ideal Man

To implement his ideas and policies, in addition to providing the above-mentioned material conditions, Tomáš Baťa also intended to shape his employees according to his vision. The company strove to create a working class composed of workers who would be loyal to the firm, which granted them employment and higher living standards. In Bata's discourse, the ideal man was clean, hardworking, and healthy.Footnote 33 The firm waged a permanent campaign against its greatest enemies, alcohol, tobacco, and gambling, which were considered a threat to stable family life.Footnote 34 Women were expected to maintain a clean, tidy house and garden, while the husband was designated as the breadwinner.Footnote 35 When women became pregnant, employment was interrupted.Footnote 36 Unmarried girls who worked in the factory were housed in dormitories for girls.

This quest for the ideal worker was also accomplished through social rationalization and the “raising” of the company's labour elite, with the goal of producing a disciplined, loyal, and dedicated workforce. In 1925, an apprentice school, named the Bata School of Work, opened and gathered people from around the world, trained according to company standards, to work in Bata factories and stores in their respective countries.Footnote 37 Such apprentice schools were later founded in the former Yugoslavia, France, the Netherlands, England, Canada, India, and elsewhere, and had a similar system and regime to that in Zlín.

Bata's goal to create the ideal worker entailed adapting recruitment practices. An analysis conducted for the International Labour Office in 1930 found that the vast majority of workers at Bata were young, aged between twenty-one and twenty-five years old.Footnote 38 Bata employees were recruited mainly from the unskilled rural population. Their combination of youth and rural origin made them receptive to the Bata training, which aimed to create homogeneous teams that would work successfully in autonomous workshops. The firm preferred not to employ urban workers, as it suspected them of already being influenced by communist and socialist ideas, making it more difficult for the company to mould them according to its preferences. Moreover, these workers had been socialized within the existing industrial tradition, and were considered inappropriate and needed further training before integrating into the Bata system. During the 1920s and the first part of the 1930s, protests were held in several countries against Bata, and the working-class population was mainly hostile to the company's expansion.Footnote 39 The wave of protests against Bata began in the mid-1920s in Germany, and continued in Great Britain, Scandinavia, and Yugoslavia. Governments in France and Switzerland even introduced so-called Lex Bata laws in the first part of the 1930s, which were intended to contain Bata's expansion and protect domestic shoe production. The success and expansion of the company was one of the major topics at the all-European congresses of the International Boot and Shoe Operatives and Leather Workers Federation, in Paris in 1924, London 1927, and Prague 1930.

Industrial Relations and the Building of Social Peace

Salaries in the Bata system were usually more substantial than average salaries in the leather industry. During the mid-1930s, the average daily wage of a worker in the leather and footwear industry in Yugoslavia was around twenty dinars,Footnote 40 while average wages at Bata were between fifty-two and fifty-eight dinars per day for male workers and thirty dinars for female workers.Footnote 41 In Czechoslovakia in the late 1920s the average daily wage in the industry was twenty-six crowns while the regular salary in Bata factories was thirty-nine crowns.Footnote 42 Women were usually paid around fifty to sixty per cent of men's wages.Footnote 43 Critics of Bata usually explained these above-average salaries with reference to overtime, exaggerated and excessive rationalization, exploitation, and workers’ alienation. The working day in the Bata factory lasted from 7 am until noon, followed by a break until 2 pm, after which the workshops stayed in operation until 5 pm. The two-hour break was used for workers’ lunch and leisure time, including cinema projections or different sports activities. However, employees who had built up backlogs were strongly encouraged to use these breaks to catch up. Most of the employees’ salaries flowed back into the firm through various channels. The flats provided by the company were rented to workers who dined in company canteens, bought groceries and other supplies in stores that were also company property, and visited company cinemas. These are just a few examples of how, through various services, salaries paid to workers ended up back in the firm's coffers.Footnote 44

The Bata company did not allow forms of organized labour other than the unions managed by the firm. The general strike in Zlín from September to December 1906, as well as a one-day strike in March 1918, followed by a strike by the Zlín factory's metalworkers in April 1919, led to this policy of banning other unions. Bata claimed that this policy aimed to avoid class conflicts, preserve social peace, and further a collective commitment to communitarianism.Footnote 45

Sport and Other Social Events: Towards Total Social Integration

The company devoted great attention to sports, founding and assisting in the establishment of various sports clubs in the factory, and encouraging workers’ participation in sports competitions. Of course, this required both an infrastructure and a favourable attitude towards the employees who promoted Bata through sport. Sport was seen as an ideal way to present healthy living, as referred to above. Sport's potential was used for advertising, and the company sponsored different sports competitions to increase the visibility of the Bata brand.Footnote 46

Another favourite pastime of the residents of the Bata company town was visiting the cinema. In most towns, films were screened in community houses, but, in some cases, as in Best, they were shown in dedicated premises in the main factory buildings. The films most often screened were of domestic or Hollywood origin. In some of the settlements they were screened every day, in others three to four times a week.Footnote 47 In addition, orchestras were established in most of the company towns, performing at various events and celebrations. Performances of professional or amateur theatre groups were also organized in the factory towns.

Besides sporting events, concerts, films, and theatre, there was an additional dimension to public occasions and various mass events. Most notable were the annual Labour Day celebrations, which were organized on 1 May.Footnote 48 The Bata Company introduced the May Day celebrations in Zlín to counter the monopolization of Labour Day by the left. This event was later transferred elsewhere, and usually included massive organizational planning, rehearsed marches of workers, sports matches, aviation exhibitions, film projections, concerts, and prepared meals for visitors.Footnote 49 A critical role in the company narrative was also played by the annual commemorations of Tomáš Bata's death on 12 July.Footnote 50

Zlín Abroad? Bata Company Towns Worldwide

Europe

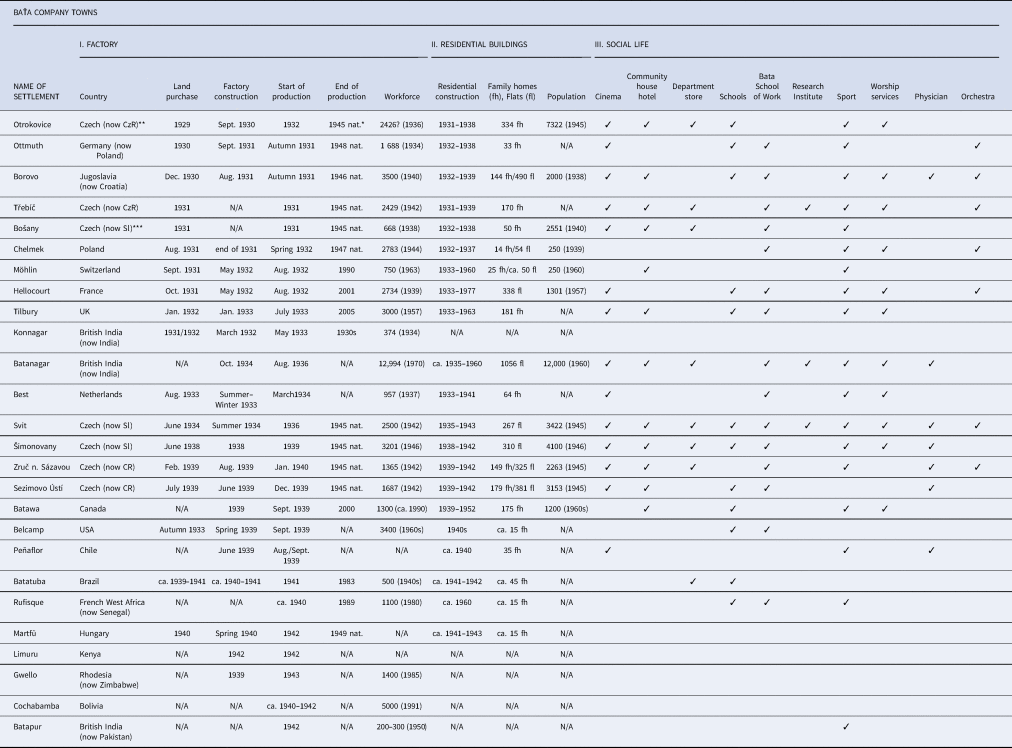

Up to now, we have defined the original Bata social welfare system as it developed in Zlín. We now analyse the evolution of welfare practices in different Bata towns worldwide and assess to what extent the Zlín model was applied (see Table 1). Rather than describing the history of all Bata settlements exhaustively, we focus on a few selected cases, which provide relevant clues on how and why institutional transfers have deviated from the original model.

Table 1. Specifics of Bata company towns.

* nat. = nationalisation

** Czech (now CzR) = Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic)

*** Czech (now Sl) = Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia)

Source: Zdeněk Pokluda, Jan Herman, and Milan Balaban, Bata na všech kontinentech (Zlín, 2020), p. 48.

While Zlín had initially developed organically, the other Bata towns in Czechoslovakia and abroad were built from scratch, and were established according to formal rules and methods drawn from the firm's previous experience. Their construction followed the idea of a clear division of production, residential, and recreational zones. The settlements were founded outside of existing urban areas in order to foster the local community's formation, and workers with rural backgrounds were recruited, rather than those from industrial areas.Footnote 51 In the majority of those company towns, in addition to the Bata owned stores, there were also small, local independent businesses, such as barber shops, bakeries, and other services.Footnote 52 The towns were to be situated on flat terrain, near a river or water channel. They needed to have convenient travel links, with railways, motorways, and airport connections. Where those transport connections were not satisfactory, the company enhanced them by building waterways, railways, and roads. Except for Otrokovice, built near Zlín, the other company towns were built outside of large urban zones. In this respect, Bata had significant autonomy over their development. Exporting the blueprint from Zlín was an enormous enterprise: as Muñoz Sanz has observed, in 1935 the company was simultaneously building no less than eight company towns abroad and six within Czechoslovakia.Footnote 53 During this process, the plans needed to be adapted not only to natural circumstances, for example in Otrokovice, but also to the different local social and political conditions. For those reasons, the outcomes were mostly different from what the architects from Zlín had planned. The original projects had reckoned with much larger settlements, numbering dozens of factory buildings, hundreds of semi-detached houses, thousands of inhabitants, and a broad and comprehensive social welfare system for employees and their families. In many cases, however, specific local constraints, historical contingencies, and social reactions to these projects (such as organized boycotts, political interference, or anti-Bata legislation),Footnote 54 resulted in more modest outcomes.Footnote 55 This process was centrally controlled from the Zlín headquarters, with very limited autonomy of the different companies abroad. This changed during World War II, however, when the occupation of Czechoslovakia impeded the control of factories and sister companies outside of the Axis occupation zone. After World War II, the global company was deliberately decentralized, after having lost the majority of its assets to nationalization in Central and Eastern Europe. The new headquarters, first in London (up to 1962), then in Toronto, only coordinated the companies’ cooperation and provided them with the necessary legal and technical support.

The Bata Company sent hundreds of its workers abroad from the early 1920s onwards. From the 1930s, these employees worked in company branches – stores, trading companies – and many of them also in factories. They usually worked in higher professional positions, trained local staff, and returned to Zlín after completing their tasks. The working stays of these Czechoslovaks were mostly limited in time, only exceptionally lasting more than a few years. For example, in Borovo, which was the largest Bata factory in Europe outside of Czechoslovakia, the number of Czechs was less than twenty at its peak.Footnote 56 Notable exceptions were large factories in Batanagar, to where more than 150 persons came from Zlín, and Batawa in Canada, where the number of Czech families was around 100. The overall number of Zlín workers abroad is not easy to determine due to the changing global political and economic conditions (economic crisis, customs measures, anti-Bata laws in Switzerland and France). To illustrate, in the period of March 1938–March 1939, the company sent 400 people abroad. Another 450 people left Zlín before September 1939.Footnote 57 According to the war statistics from September 1944, 1032 employees from Zlín worked in the unoccupied allied part of the world.Footnote 58 With the growing danger of German Nazism, Jewish workers were sent abroad to a greater extent after March 1938.Footnote 59

The Bata workers from Zlín were trained to adapt to the local religious, linguistic, social, and cultural conditions, as it was the company's aim not to alienate public opinion in the respective host countries. For this reason, the firm respected the local religious and cultural traditions, and supported the construction of religious buildings such as Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches, as well as mosques and Hindu temples. Tomáš Bata himself urged employees who were sent abroad to adapt to the local lifestyle, use the language of the host country, consume the local cuisine, and respect the local traditions and culture. While the Bata management promoted internationalism and wanted to create a transnational class of Bata-men, the results were embodied, as Zachary Doleshal observed, in “a complicated cosmopolitanism”.Footnote 60 The Bata modernist vision of the creation of a global class of Bata-men, regardless of their race, nation, religion, or culture, was confronted with increasing nationalism and chauvinism in the 1930s.Footnote 61

We identified fifteen Bata settlements founded in Europe during the twentieth century. Initially, the company built small copies of Zlín within Czechoslovakia, and then went on to establish company towns in other parts of Europe, following the same pattern. Two case studies are depicted here, one in Southeast Europe, and a second in the western part of the continent. The first is Borovo in Yugoslavia. In this country, the firm achieved almost the same status and success as in its home state, dominating almost 90 per cent of domestic shoe production.Footnote 62 The workers’ conditions, in terms of the level of welfare services provided to them, were closest to those in Zlín. As the social welfare system in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was in its infancy, and insufficient,Footnote 63 the Bata Company needed to take on a more substantial role, supplementing the state institutions to a large degree. The firm financed a vast social services network. It built over twenty public buildings, among them three primary schools, a kindergarten, a cultural and community centre, a clinic, a post office, a railway station, a bakery, sports grounds, a swimming pool, and an ice rink.Footnote 64 These benefits brought the system's level almost in line with that in Zlín. At the end of the 1930s, around 2000 inhabitants lived in 147 buildings containing almost 500 flats, and in three dormitories for unmarried workers.Footnote 65 However, the majority of the approximately 4500 workers employed by the factory did not obtain the highest company benefit, namely, of living in modern brick houses. They lived in villages around Borovo, which saw large increases in building projects.Footnote 66 The Bata Company tried, as it had done in Czechoslovakia, to create the perfect worker for the modern industrial age. As elsewhere, recruits were young workers from rural areas, who were trained under Bata standards. The company newsletter, Borovo, which was published twice a week, played an important role in instilling the desired worldview in employees.Footnote 67 It promoted not just how the ideal man and woman should work and behave, but also a healthy lifestyle and abstinence from vices.Footnote 68 It seems that the majority of the workers in Borovo and the surrounding area had a positive relationship with Bata and the opportunities it provided.Footnote 69 The situation was different on a national level, however. The company was the target of a series of protests and boycotts, which lasted from the mid-1920s until the second half of the 1930s, and the Yugoslav government prepared – but did not use – similar legal measures as those seen in France and Switzerland.Footnote 70 Resistance towards Bata was motivated not only by its suffocating and suppression of domestic competition, but also because, as the Union Federation stated: “The Bata company develops so-called industrial feudalism, in which it controls all the needs of its workers, and behaves as master of their needs.”Footnote 71 They also condemned the firm's practice of building company towns outside of the larger urban areas, as it isolated Bata employees from other workers.Footnote 72 In the case of Borovo, the development of the town was closely connected with the success of the company, with the local government in control of the firm, as Toma Maksimović held the position of the town mayor, just as Tomáš Baťa did in Zlín. Borovo was nationalized after World War II. This nationalized company, which later became one of the ten largest firms in socialist Yugoslavia, was an engine of development for the entire region of Eastern Slavonia, and, at its peak, in the 1980s, it employed more than 23,000 workers.Footnote 73

In its first years, the Bataville settlement, founded in the east of France, benefited from the great expansion of the French branch of the company. It became one of the largest Bata towns and hosted one of the company's most productive plants worldwide. It was equipped with a runway for airplanes, a community centre, a school, a swimming pool, outside sports grounds, a post office, sports hall, church, and professional training centre. Bataville also had a factory orchestra, cultural and leisure activities, such as regular weekend entertainment events and balls, and a sporting club under company control. Bata owned a farm that supplied the company restaurant and store in the town.Footnote 74 These amenities and social activities indicate a particularly important endeavour of the firm in the region, as compared to other settlements. Further evidence of the company's special interest for this site is evidenced by an ambitious project for the extension of the city involving the famous architect Le Corbusier, in the first half of 1936. His plans for a renewed and extended Bataville were finally rejected by the firm due to their exaggerated scale and their deviation from the urbanistic canons of the company – Le Corbusier proposed, for example, replacing individual houses with apartment blocks.Footnote 75 As we see, this clash between garden city and modernist-urbanistic approaches ended in favour of the company's original plans, which followed Bata's founding principles. The year 1936 also witnessed the promulgation of an anti-Bata law (the so-called Le Poullen law), resulting from a massive political and lobbying campaign against Bata within the shoe industry. The new legal constraints substantially hindered the development of the French branch of the firm, which had to reorient its strategy towards improving its production and retail system without expanding it as planned.Footnote 76 The growth of Bataville, therefore, never met the expectations of the Zlín headquarters: instead of 13,000 inhabitants, it barely reached 1400 inhabitants after World War II.Footnote 77 As elsewhere, Bataville did not host all the factory's workers. Throughout its history, the company town provided accommodation to one third of them, while the remainder commuted from the small villages scattered around it. While Batavillois and workers from the rural villages shared similar working conditions within the factory, their everyday lives were notably different given the distance to the amenities and social institutions located exclusively in Bataville.

Social welfare practices in Bataville were initially heavily influenced by the Zlín model, but as the French legislation evolved some adaptations were made. Hence, a few weeks before the adoption of the forty-hour working week legislation by the French national assembly, the journal Bataville announced a reduction of working time to forty hours per week. Given the context of social uprising in the Front Populaire, this proactive measure by Bata managers appears as a potential means of avoiding strikes and political socialization. As early as 1939, the working week was extended to forty-five hours and only returned to forty hours in the 1970s.Footnote 78 The patterns followed by Bata's paternalistic practices in Bataville were often affected by the development of public social welfare services in France. Hence, the 1946 law on works’ councils resulted in the firm abandoning several prerogatives, such as meal tickets or the handling of the budget devoted to festivities and commemorative events. When Bataville was founded, its environs were characterized by the absence of public childcare services. Gender relations were organized by socially defined roles for men and women, ascribing most of the domestic work and childcare to the latter. Hence, most of the time, the female workforce in the factory was young, single, and childless.Footnote 79 When facing a labour shortage, Bata executives could easily mobilize a new labour pool by offering work at home or setting up small rural production units in the surrounding villages. By the same token, employees’ transportation costs were reduced and specific products with slow production cycles, such as moccasins, could be manufactured outside the factory, allowing for faster cycles in the production lines, where only the most standard products were made. At the end of the 1970s, one third of Bata's female workers were working outside the factory.Footnote 80 In this way, the Bataville settlement deviated from its original industrial model, which was based on concentrated manpower in a single factory.

Asia and Africa

The largest of the Bata company towns outside of Europe was Batanagar in India, on the outskirts of Kolkata. The design of the company town and the factory complex was devolved to F.L. Gahura.Footnote 81 The foundation stone for the settlement was laid on 28 October 1934.Footnote 82

Because of the tropical conditions, the factory buildings in Batanagar were made from reinforced concrete, instead of the usual Bata combination of red bricks, steel, and concrete.Footnote 83 The company also provided medical services with the opening of a clinic, and subsequently introduced dental care.Footnote 84 The firm introduced ten days of unpaid leave, which was usually taken during Puja season.Footnote 85 A mosque was built in the settlement, and a chapel for the Christians.Footnote 86 A Hindu temple was also added later. In September 1937, the Bata School of Work was founded to train a suitably qualified workforce. A sports hall was built for indoor sports activities, as well as a football stadium.Footnote 87 A Bata club, with a swimming pool and tennis court, was also constructed. Typical Bata events were held in the settlement, including May Day celebrationsFootnote 88 and the commemoration of Tomas Bata's death in July.Footnote 89 Until the end of the 1950s, 1056 housing units were built in Batanagar, as well as dormitories for unmarried workers with 2400 beds. Around 12,000 people lived in the company town.Footnote 90

The Bata company town in India differed in some details from those in Europe and, as we shall see below, North America. Accommodation for Europeans and Indians was separate, on different sides of the factory complex. Around 150 Czechoslovaks lived in the European part of the settlement at the end of the 1930s. With the exception of the higher-management villas, their accommodation consisted of two-storey houses, all of which had a lounge, kitchen, and a pantry on the ground floor, and two bedrooms and a toilet on the second floor, as well as a terrace and a small garden.Footnote 91 On the other hand, the housing for Indian workers comprised six flats in one building for higher-level employees and a collective settlement for ordinary workers.Footnote 92 A community centre, which also served as a cinema, was built to meet the Indian workers’ social needs. These differences in accommodation standards were among the main reasons for the workers’ unrest in January 1939, which lasted two weeks.Footnote 93 This was by far the most significant workers’ protest in the overall Bata international system. Subsequently, the company invested significant funds in improving the living conditions of the Indian workers.Footnote 94 Even before that, however, the company systematically promoted Indian employees, and, already in the second half of the 1930s, several departments in the factory were managed by domestic employees. Their number increased over the years, and, in a process that lasted from the second half of the 1940s to the mid-1960s, they completely replaced the Czechoslovak management, while adapting the business to a policy of “Indianization”. This was a continuation of attempts by the company management to build on its good relations with the Indian elite, which had been in place since the 1930s, when the Bata family organized several visits of Indian politicians and businessmen to Zlín. They even sent a plane to Prague in order to bring Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira to Zlín in August 1938.Footnote 95 In the early 1930s, during the initial phase of the establishment of the enterprise in India, the company had been on the verge of a social boycott by other Europeans in Kolkata, who resented Bata's policy as insufficiently “white” due to the company's lack of social distance from the native inhabitants and the small salary gaps between the Czech and Indian employees.Footnote 96 Without concrete evidence, we can only assume that, during the building of the company town, the measures for dividing settlements into European and Indian areas were introduced in order to avoid such problems.

While Bata's presence in India was carefully planned and executed, the establishment of the company's factories in Africa was necessitated by the occupation of Czechoslovakia and World War II, when the company needed to establish new production centres because the vast majority of its resources were in countries under German occupation. For this reason, and due to the haste with which settlements were founded, they lacked the facilities and social services that had been built in Europe or Asia. The larger of the two African Bata towns was in Limuru, Kenya, thirty-five kilometres from Nairobi. In 1942, a new factory was built, along with a residential complex for employees with brick houses. Leather and rubber footwear, as well as clothing, were produced in five factory buildings. The number of employees increased, reaching 1400 in 1946.Footnote 97 The company also provided a football and basketball court, tennis courts, and a children's playground in addition to accommodation facilities. The other Bata factory town in Africa was located in Gwelo in Rhodesia (today, Gweru in Zimbabwe).Footnote 98 Gwelo was built based on a pre-war plan for an industrial village of 300 inhabitants and represented a unique project of its type.Footnote 99 The firm established a factory in 1939, soon to be followed by the company's residential complex, which included the building of accommodation units for employees, a school, sports playground, and the Bata Club. Different cultural and social activities were organized. As the accommodation in Gwelo was not ideal, significant investments were made in its modernization during the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 100 Given that more detailed data on these settlements is currently unavailable, it is not possible to determine whether their social welfare regimes were typical or atypical with regard to the dominant local patterns of so-called labour reserve economies, i.e. the colonial imperative of employing cheap labour that was characteristic of Kenya and Zimbabwe until the 1970s.Footnote 101

If we compare the Bata towns in Europe with their counterparts in Asia and Africa, the only one that resembled the European towns was Batanagar. This settlement became one of the most enduring Bata towns, and it came close to the ideal imagined by Bata. With its long-term partnership between the local community and the company in terms of social, economic, and technological dimensions, Batanagar became synonymous with Bata in India. This company town's longevity is also connected with its full identification with India and not with colonial rule. From the outset, some of the crucial roles in the development of both the town and the company were held by Indian citizens. With regard to the standard of the social welfare system, this practice was very advanced if we compare it with the colonial company towns of Fushun in ManchuriaFootnote 102 or Catumbela in Portuguese Angola, for example.Footnote 103 There was no overt racial discrimination in Batanagar and, apart from the housing conditions for local workers, the level of welfare facilities was high. Even the housing situation improved considerably after the 1939 strike. While Batanagar was built according to plans from Zlín, partly adjusted to domestic circumstances, the African Bata towns, Gwello and Limuru, were built amid the haste and chaos of World War II. For this reason, they looked more like industrial villages, with a lower level of welfare services, than the carefully planned and implemented Indian Bata town.Footnote 104

The Americas

Unlike in Europe and in Asia, the Bata company towns in the New World were erected under extraordinary circumstances, during World War II. Just as in the African cases mentioned above, the American company towns raise questions as to why they turned out different from the initial plans and, more generally, from the model town of Zlín.

For various reasons, the American continent was a unique location for the Bata company during the Interwar period and World War II. First, Bata's presence there was negligible in terms of factories and urbanization until 1939. Second, the towns had to be hastily organized with imported machinery, which created only the necessary infrastructure, usually a factory and dwellings. Third, the plants and towns were built during difficult economic times, which prevented substantial investment and growth because resources were scarce. Fourth, the organization had to be more decentralized as a result of Thomas J. Bata falling out with his uncle Jan A. Baťa.Footnote 105 Fifth, the socio-cultural system was primarily used for the Czechoslovak immigrants and refugees – staff, workers, and their families. All these circumstances led to a more pragmatic approach on the American continent. It inevitably led to a limited version of the Bata towns and their associated social welfare system. The company's presence in the Americas is demonstrated in the two largest factories and towns, established in 1939 and 1940, respectively: Batawa in Canada and Batatuba in Brazil. However, the corporation also established other settlements, in Belcamp in the US, and in Peñaflor in Chile.

The Bata company's presence in Canada was planned at the beginning of the 1930s, with the idea to build a small enterprise. Eventually, in 1938, the Munich Agreement stripped Czechoslovakia of its border regions, leading to a reassessment of the idea. Thomas J. Bata was in charge, and visited Canada to look for a suitable area to build a new town. The Quebec government offered him several possibilities, which he refused because of the French language barrier that company workers would have to overcome. Later, he found an ideal spot in Ontario, in the Trent river valley, with a power supply, railway, highway, and a navigable river. Today, the place is called Batawa.Footnote 106 In the subsequent months, Thomas J. Bata transported machinery from Zlín to his employees’ location. Problems with the Canadian government arose, as it had restricted the immigration of factory workers, favouring farmers. As a result, only 100 instead of 250 families were accepted. The machinery came to Canada on a German ship, which then refused to unload the cargo.

The nearby town of Frankford, with 850 inhabitants, relied on the paper industry, but the factory had closed during the Great Depression.Footnote 107 Bata took over the factory and launched an improvised production while simultaneously embarking on plans to build an industrial town.Footnote 108 Nevertheless, the original plans had to be sacrificed:

The first street of this new Ontario township of the future – still without a name – was laid out according to a plan which envisaged the development of an industrial community of some thousand people. […] The hell which gaped open in Europe during the fall of 1939 swallowed all the great plans for a new model industrial town in Canada. Instead of a town, only a small village sprang up around a medium-sized rather than full-sized plant.Footnote 109

Furthermore, even production had to be adapted to the war effort, so that Bata could gain political capital among the Allies and use the resources available.Footnote 110 Batawa did not resemble Zlín but was merely a provincial town. It was built around a main boulevard with stores, offices, and public buildings on both sides. The five-storey factory building was surrounded by a Bata hotel for single workers and a recreational hall used by the residents as a theatre, cinema, and indoor sports gymnasium.Footnote 111 In the surroundings, a village of two- or three-bedroom houses appeared in 1940.Footnote 112 The lodgings had to be rationed because the prices were three-and-a half times higher than in Czechoslovakia, and just 185 houses were built. On the other hand, they still offered affordable conveniences and featured a kitchen, dining room, bathroom, two bedrooms, and a cellar.Footnote 113

During World War II, Batawa occupied an elevated position in Bata's organizational hierarchy. Even though the corporation's structure was decentralized and sister companies were autonomous during the conflict, the temporary headquarters, where Thomas J. Bata managed the company, was located in Canada. This led to an elaborate social welfare system in Batawa, unparalleled elsewhere in Bata's American enterprises. Employees – at first only key staff and their families, later all personnel – received life and sickness insurance, workers’ insurance after six months, family insurance after two years of service. For the purposes of social life and to maintain a connection with their homeland, the staff received a mimeographed daily newspaper, a home broadcast of daily news, a 16-mm cinema, a church, a market, and a cafeteria, where meetings could be organized. A night school for studying English, a parents’ committee managing the children's education, tutoring for forepersons and key management personnel, and the company's training of unskilled labour were set up. Another association was the local division of “Sokol” (Falcon), a gymnastics, sports, and cultural club.Footnote 114

The development of Bata's welfare practices in Batawa was shaped by the specific context of Canadian social welfare measures. After World War I, Canada started to undertake several social reforms on a federal level, albeit half-heartedly: veterans’ benefits; a modest programme of social housing; a national programme of employment exchanges; and the introduction of an old age pension that was financed by both the federal and provincial governments. Most provinces also offered widows’ allowances, sometimes also used to assist abandoned wives.Footnote 115 After the Great Depression, the social welfare programmes remained almost the same. The Dominion Housing Act of 1938 was rejected in Ontario, so it did not apply to Batawa.Footnote 116 It was not until July 1941 that the prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, announced that the federal government would have exclusive control over unemployment insurance.Footnote 117 The social system remained fragmented until the end of World War II, however, and had many gaps, including health insurance or a minimum wage. Some provinces offered the latter, but it was so low that it could not cover family expenses, and it was possible for employers to evade the law.Footnote 118 These efforts were followed during World War II by six documents prepared by the advisory committees of the Canadian parliament. One of these documents was the import report by Leonard Marsh, prepared in 1943, which is considered by many to be the foundation of Canada's social welfare system. Nevertheless, the social welfare measures that were debated and approved were implemented only gradually, in the years following the war.Footnote 119 When Thomas J. Bata came to Canada in 1939, he was aware of the macro-social measures that were instituted by the federal and provincial governments, and so he focused on the micro level, especially when he realized that many of the Canadian programmes were either not applicable (pensions) or useless (veteran's benefits, mother's allowances) for many of his employees. He therefore focused on housing problems and healthcare. Many Canadian companies also introduced similar welfare programmes in the Interwar period: sickness insurance; mortgage loans; and recreational programmes to foster worker loyalty.Footnote 120

The importance of the Bata social system, however, also lay in the sphere of immigration policy and welfare. The Canadian government had no integration programmes and merely provided newcomers with information about job opportunities, or introduced restrictive measures, as in 1931, when it admitted only Czechoslovak farmers with sufficient capital.Footnote 121 In 1939, Bata fought this legislation, with partial success, guaranteeing jobs to the newcomers and providing integration measures, such as English lessons. Similar to that of Batawa was the case of Belcamp in the US. The factory there was founded by Thomas's uncle, who also had big plans that, ultimately, were not implemented. Jan A. Baťa's problems were not purely financial; the Allies blacklisted him for failing to condemn Adolf Hitler. He claimed he could not condemn him because it would threaten all the employees in Zlín, but the US administration refused to prolong his visa and he had to move to Brazil.Footnote 122

In 1941, Jan A. Baťa established his headquarters in Brazil. After Munich, the company had started a production unit in a rented building in São Paulo, which was to serve as a springboard for the construction of the industrial city Batatuba. When Jan Antonín arrived, the factory was already operating, albeit in a hastily constructed shed. There were some refurbished houses and some better homes for Czechoslovak employees. The workers had to be transported every day from the nearby city of Piracaia.Footnote 123 The city started to grow, but never reached the planned capacity of 10,000 inhabitants. The factory was not profitable until 1942, when Brazil entered the war. Even then, the resources were limited, and the number of workers rose to just above one thousand.Footnote 124

Thanks to plans dating from 1948, we know precisely how Batatuba was intended and what it looked like during World War II. Its social welfare system was more ambitious than those in North America, presumably because the city was situated in the middle of a rainforest. After the factory and warehouses, community buildings started to appear, first the houses, each for a single family, then residences for the management and for J.A. Baťa himself. Subsequently, to provide food the company built a marketplace, a canteen, and a butcher's shop. From the outset, education was crucial in Batatuba; as early as 1942, two schools, one mixed and one industrial, were set up for workers and their children. “The Industrial School taught classes at night, in mathematics, history, ‘physical education’, accounting, Portuguese, calculus, arithmetic, mechanics, ‘shoe selling.’ Also, a building for singles was erected in the middle of the residential area, whose aim was to receive young apprentices, and it seems to have also functioned as a hotel for war refugees.”Footnote 125

The Bata company also provided community services. It published the newspaper Novidades de Batatuba and ran a community centre with a cinema. There, a band composed of students from the industrial school practised and organized dances. There was an emphasis on physical recreation, and the local park served as an ideal place to take time off. A football team and a basketball team were established. Nevertheless, the social welfare plans had been even more ambitious. The blueprints include buildings such as a social centre, a social institute, a church, and a hospital. According to documents from 1948, none of them was constructed.Footnote 126 Jan A. Baťa established other cities in Brazil during World War II, such as Vila CIMA or Mariápolis, but these remained secondary and in their incipient phases, never outgrowing Batatuba in terms of importance.Footnote 127

By the time Bat'a arrived in Brazil, the country and its social system were already going through a period of dynamic progress. Getúlio Vargas had come to power in 1930 and retained it for the next fifteen years. The new regime had emerged from the deep crisis of the so-called First Republic, whose oligarchic government had been unable to challenge the growing agricultural crisis, intensified by the Great Depression, and to respond to increasing pressure from the urban working and middle classes.Footnote 128

Vargas's regime had placed the social agenda, together with industrialization, among its priorities, as both problems were intertwined in Brazil. He is therefore labelled by historians as the author of a social revolution in the country that, for the first time, allowed “people to enter into history”.Footnote 129 These efforts were coordinated by the new Ministério do Trabalho, Indústria e Comércio (Ministry of Labour, Industry and Commerce), established in 1930, and the Institutos de Aposentadorias e Pensões (pension and benefit institutes), introduced in 1934. The labour legislation was consolidated in 1943, but remained in the developmental phase until at least 1964.Footnote 130 The pillars of Vargas's social system were the nationwide labour union structure, the social security system, labour regulations, and the imposition of a national minimum salary. These measures did not make up a universalist social welfare system, however, but were rather parts of a corporatist model that suited the state. Other areas, like education or health, underwent certain changes but did not occupy a central place in the agenda or were neglected.Footnote 131 It is also worth highlighting that these social policies served the purposes of the ruling elites by providing them with mass support. It also facilitated government control over the workers and the unions, which authors often label as “public trade unions”. Overall, Vargas's social policy can be categorized as a corporatist meritocratic–individualistic model of social solidarity that imposed restrictions on democracy.Footnote 132 Furthermore, the system was selective. It was focused on the largest urban centres and completely omitted peasants and rural workers. Similarly, it was oriented towards those professional categories that were politically and productively important.Footnote 133

Batatuba was established in the state of São Paulo, one of the most industrialized in Brazil. As in Batawa, here Jan A. Baťa could rely on the macro-social measures introduced by the Vargas government. Especially after 1942, when the country entered the war, the importance of the company grew. Baťa also took advantage of the pension system, which was instituted as a national scheme, but which was decentralized by the economic sector and regulated by a specific state agency.Footnote 134 Nevertheless, the limitations he had to endure because of the lack of capital are clear. The decision to build a city almost on a greenfield site was too ambitious, and much of the company's funds ended up in the building of a basic town infrastructure. Like his nephew, Jan Baťa also focused on the integration of Czechoslovak refugees as employees,Footnote 135 providing them with housing, education (Portuguese lessons), and leisure. Most of the locals commuted daily from the city of Piracaia and so did not benefit much from the town's infrastructure and local welfare. Jan A. Baťa intended to improve Batatuba's welfare system by building a social institute or a hospital, but financial problems led him to focus on the more lucrative construction of further factories across Brazil.

Conclusion

Bata's extensive social welfare system in Zlín primarily drew upon its vision of an ideal industrial town. While the company strove to replicate its social system in other settlements worldwide, policies and practices ultimately followed diverging paths. Rather than clones, Bata company towns have developed more like grafts. The firm's ambitious plan to scatter the Zlín model over the globe was therefore never fully realized.

The emergence and development of Bata's social welfare system can be viewed in the context of how multinationals engage in globalization through institutional transfers, and under conditions in which these transfers deviate from the original plans. In the Bata case, three main dynamics caused divergence between its settlements around the world. First, the company had to make pragmatic adjustments to its original model in order to fit into the local environment. This happened especially in non-European locations, such as Batanagar, where colonialist relations translated into segregated urban planning and housing. Second, the changing legal, economic, and social conditions induced the company to implement medium-term adaptations to its local infrastructures and policies. This dynamic has been observed in all continents. The trajectory of the French settlement is a good example: Bata renounced an ambitious expansion plan for its town when faced with an anti-Bata law; later, it reduced the scope of its welfare provision as the national social protection system expanded to include new prerogatives. Third, divergence between settlements could have resulted from the evolution or erosion of the model itself. Bata's efforts to develop an extensive welfare system became diminished between the time of the foundation of the European settlements in the early 1930s and the building of company towns in other continents within the uncertain context of World War II. The lower number of amenities and services in the second wave of settlements clearly illustrates this shift.

These results contradict any linear conceptions of an institutional transfer of business policies and practices from the country of origin to several different locations abroad. Our research shows instead that Bata welfare policies and practices were shaped by transnational activities, from the design of the original model to its transfer to other locations. In this process, the socioeconomic and legal framework of the nascent welfare states and the local dynamics of social relations played a major role in the differentiation of the multinational's social welfare practices. In this process, the company kept a degree of agency that allowed for a re-evaluation of the original plans and, in many cases, an adjustment of its welfare commitments. Bata became increasingly disengaged in this area after the 1950s, in a context marked by the continued rise of the welfare state, the eroding legitimacy of industrial paternalism, the nationalization of Bata's assets in socialist countries, the decolonization process, and, especially after the 1970s, the global shift of the economy to a more financial capitalist approach. The post-war decades therefore saw the decline of one of Bata's most – if not the most – singular dimensions: its social welfare system. Paradoxically, in terms of business strategies, Bata's cross-border expansion between the 1930s and the 1950s foreshadowed many business strategies of modern multinational companies from the 1970s onwards (the establishment of production facilities on a global level; a constant search for resources, labour, and new markets; introduction of technological innovations into the production process). In this respect, we raise the more global question of how these interconnected dynamics in the field of multinational companies actually relate to the recent history of nation states, and, in particular, their increasing isomorphism.

Among the many avenues for future research, we stress the issue of labour relations and conflicts (mainly through the collection of primary data on events in the African Bata towns). Because of our primary focus on welfare policies and practices, an analysis of workers’ experiences of their living and working conditions in Bata company towns was beyond the scope of this paper. A more meticulous socio-historical analysis of the social control exerted by the company, the forms of resistance or conflict that workers engaged in, and the role and depth of unions in this process, are crucial to providing a full account of Bata's transnational operation.