In the push to provide further interaction with museum and heritage exhibitions, the internet has become an established venue, offering nearly unlimited space and options for providing extensions to in-person content. These internet-based supplements in many cases outlast the physical displays they are meant to accompany. After the exhibitions have closed and the museums have moved on, the digital content remains, a static placeholder for a particular viewpoint on heritage, curation, and public outreach. Such is the case with the Interface Experience, the Web extension to the exhibition of the same name, which ran for a few months in 2015 (Bard Graduate Center [BGC] 2014a). This site, which remains largely functional, is now disconnected from the exhibition it was meant to accompany, leaving it to stand alone as a study on the connections between digital outputs and materiality.

WHAT IS A DIGITAL EXTENSION?

It is rare now, across the worlds of museology and heritage, to encounter an exhibition without an accompanying digital presence, though these outputs vary from large-scale independent digital installations to minimal mentions on internal websites and vary as well based on national standards. These outputs may be mirrors of the physical exhibition, organized to emphasize the material highlights on offer, or may be contextually based, with the goal of providing more textual information than modern exhibition design permits. Typically, they provide pre-experiences and are centered around drawing the user into the physical space of the exhibition (Gorgels Reference Gorgels2013; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2015). In short, they are enticements.

After the exhibition has ended, however, these enticements remain, attempting to engage the user with an experience that no longer exists. The digital content persists, long after the museum cases have been refilled and the exhibition space has been reappropriated. As digital extensions, they typically serve a clear (if often questionably successful) purpose, but what purpose do they serve, if any, in their postexhibition life? Most digital extensions do not change form. There is very rarely a plan for the curation of a digital extension, and in their role as promotional materials, they are not updated to serve any postexhibition purpose.

As artifacts of process, these abandoned digital outputs provide an opportunity for an engagement with our recent digital heritage and with the development of digital outputs in the heritage sector. One example, the Interface Experience, is provided for review of the potential for that engagement.

WHAT IS THE INTERFACE EXPERIENCE?

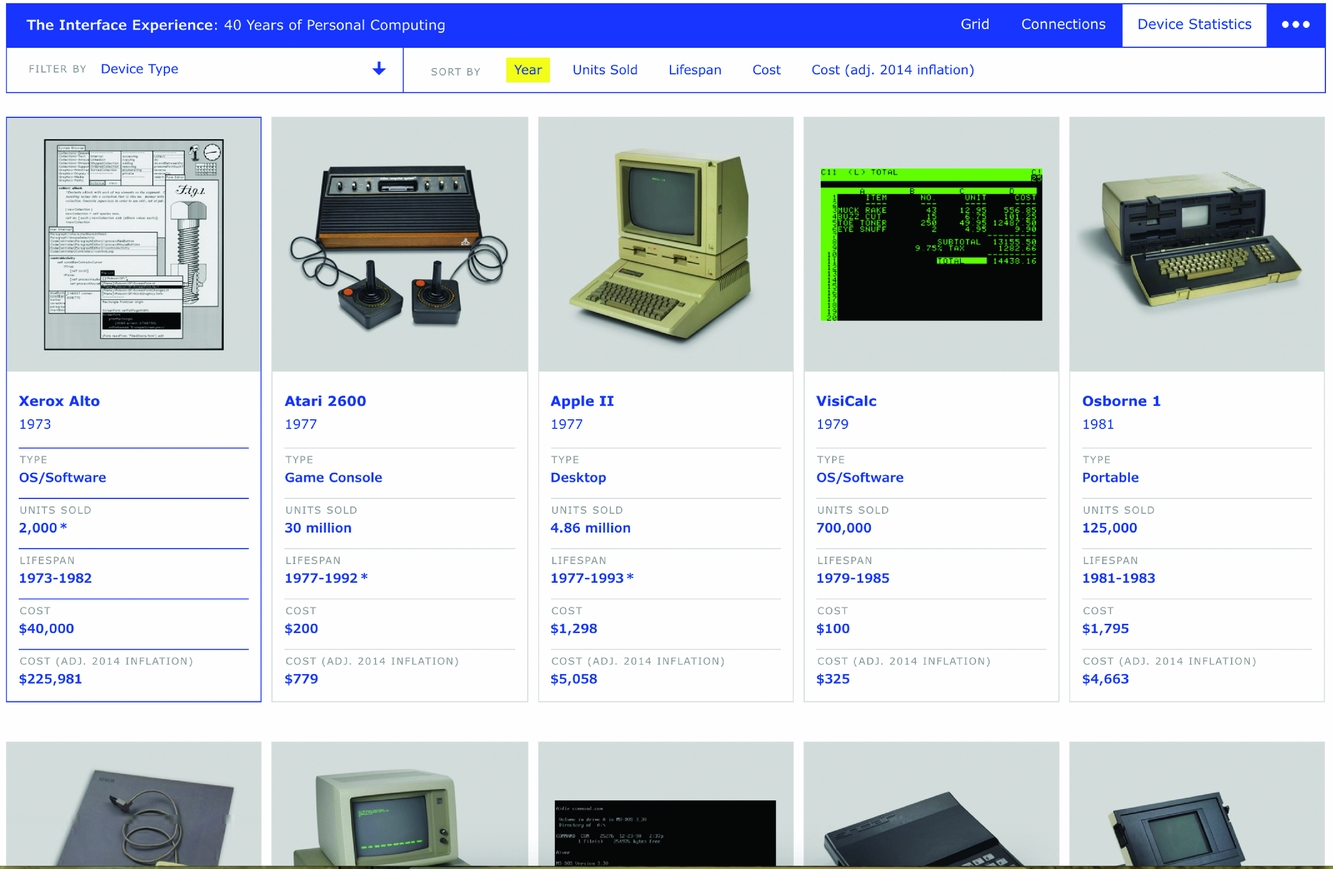

The Interface Experience Web presence (Figure 1) was created in 2015 to accompany the physical exhibition of the same name and was organized and implemented by staff and students from the Bard Graduate Center (2014b). While the physical exhibition ran from April 3 to July 19 of that year, the accompanying digital output, a graphic database of 40 years of personal computing and connected devices, is still available online. The main functionality of the site remains, though some pages that rely on external user-generated submissions are without content (BGC 2014c) and others have become inaccessible due to link rot (BGC 2014d). In other words, internal navigation links continue to function, but navigation to individual pages from outside of the site is difficult.

FIGURE 1. “Grid” mode of the Interface Experience Web extension, the default view of the site and organized chronologically, with no regard for typology within the technology displayed.

On the site, data concerning personal computing devices are available in three formats. The first format, referred to as “Grid,” is a tiled graphical interface, where images of the technology provide links to dedicated web pages that include product histories and examples of advertising and promotional materials. The second format, referred to as “Connections,” is also a grid interface, where the selection of an object shows its connection to other objects in the exhibition. The third format, referred to as “Device Statistics,” is a graphical database, where statistics on sales, typologies, and costs (both original and adjusted for 2014 inflation) can be sorted and viewed (BGC 2014e).

In itself, the technology on offer through the site is a snapshot of the range of personal computing devices that have passed in and out of modern life over the past 40 years. It is not a comprehensive database, and the selection criteria for which objects made it into the assemblage, and which were omitted, are unclear. Apple and Microsoft dominate examples of computing hardware and peripherals, and Nintendo illustrates more than one example of game technologies, but aside from a solid slate of examples illustrating the variety of the early computing industry, the gaps in the database are noticeable. Mobile technologies are underrepresented, and the move to an internet-based communications economy is represented solely by one piece of browser software, Netscape Navigator circa 1994 (BGC 2014f). What qualities led to the inclusion of the HP Compaq TC4200, a precursor to modern tablets, but not the Nokia 3310, the phone that popularized SMS messaging (BGC 2014g)? Why is Apple's Magic Trackpad, which exemplified early gestural development, present but not the ubiquitous AOL CD mailer (BGC 2014h)? As both a stand-alone database and an exhibition accompaniment, no part of the Interface Experience Web presence indicates what qualities of user experience, economics, or materiality went into the design of the site content or the exhibition content, raising questions about the effectiveness of the Web presence both in its concurrency with the exhibition when it ran and now, as a digital placeholder for memorializing its content. Taking the site as it is, three questions arise: (1) Is the Interface Experience Web presence effective on its own? (2) What function did the Web presence have in facilitating the physical exhibition? and (3) What lessons can we take from this as regards our collective digital museology and heritage practice going forward?

The website is well organized. It does not yet feel dated aesthetically or systemically, largely due to the interface, which is based around a selection of artfully photographed images of (mostly) hardware tiled against white space. Of the three modes (Grid, Connections, and Device Statistics), the Device Statistics mode (Figure 2) is the only area that allows for user control over sorting and prioritizing data. Unfortunately, one of the most interesting aspects of those data, original sale cost versus inflationary cost (an area that could potentially speak to the relative value of a piece of technology vs. earning power), is locked for an adjusted 2014 value. Coding that section to draw from an external source of inflation rates, such as those provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (US Department of Labor 2017), would have future-proofed the site to increase its value for potential users beyond the life of the website's initial development and deployment. As well, none of the database information is available in any exportable format. The bibliographic information for the Web presence (and for the exhibition and accompanying exhibition book) provides a good set of resources (BGC 2014i) but is buried as a link among a great deal of other links on a text-heavy “About the Exhibition” page (BGC 2014b) and is hosted off-site in a proprietary collection, increasing the likelihood that it will itself be unavailable in the future (Law and Morgan Reference Law and Morgan2014).

FIGURE 2. “Device Statistics” mode of the Interface Experience Web extension, the closest the project gets to providing the user with the ability to manipulate and sort data.

Information provided in the credits of a video about the exhibition notes that “the Interface Experience exhibit was a faculty-student collaboration, part of a BGC Focus Gallery project that developed out of a year-long course sequence in 2014” (BGC 2015). An additional note on the “About the Exhibition” page indicates that the Web presence was intended to further contextualize the objects selected for the physical exhibition, providing “insight into the place of each of these devices in the history of personal computing, by both telling their individual stories and building multiple connections between the objects” (BGC 2014b). So if the Web presence was designed to provide context for the exhibition, and the exhibition ended, why was the Web presence left active? The Interface Experience Web presence illustrates a common reality in digital extensions for heritage and museology. There is a plan for an exhibition, a plan for a digital extension to that exhibition, and no plan for the postexhibition curation of digital extension outputs.

When digital outputs are the result of student labor, as is the case, in large part, with the Interface Experience, there is an additional consideration that needs to be resolved in planning beyond the period of enrollment of the students involved. Once student investment in the project has ended, should the extension remain accessible, or should it be removed? What responsibility, if any, does the institution have to the maintenance of the output, and what responsibility, if any, do the involved students have in its physical or financial continuance?

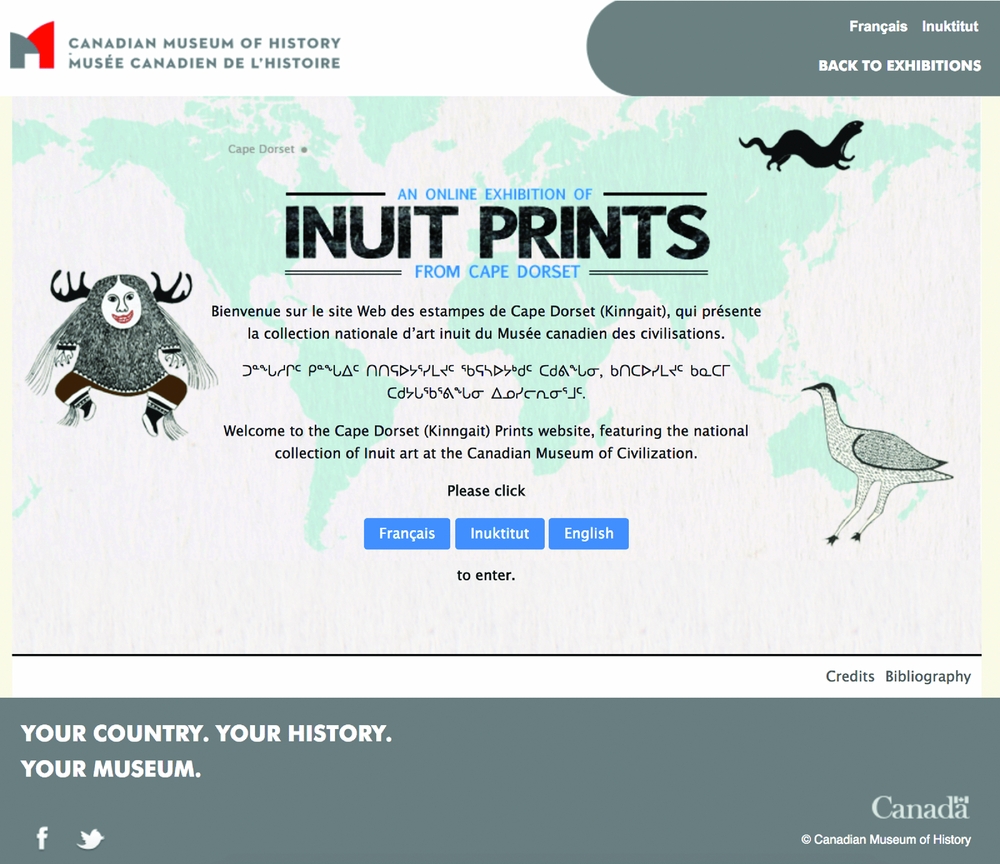

In the best of cases, such as that of the Canadian Museum of History's Online Exhibition of Inuit Prints from Cape Dorset (2014), a digital extension remains accessible, or is created to function independently, and has something to say on its own. In the case of the print exhibition extension, the digital output (Figure 3) highlights materials held by the museum but is an entirely self-contained experience, with a design directive to promote the ethical collection of contemporary materials. The extension can be read to comment on museum acquisition practices, the relationship between collections and owners of cultural patrimony, and the importance of considering audience; the extension (with a few hiccups) is available in French, English, and Inuktitut.

FIGURE 3. Canadian Museum of History's online extension of its collection of modern Inuit printmaking, which stands alone without the physical exhibition and provides translations in French, Inuktitut, and English.

The Interface Experience website, considered in this way, can be read on its own as a digital experience, providing a viewpoint from early-career academia circa 2014 on the ways in which technology is rooted in an innate self-centeredness, the way it provides pseudo-personalization through minor variation in hardware choices, and the way it relies on catering to current attitudes on materiality and the imagined future. The Interface Experience Web presence does not necessitate user access to the physical exhibit, though without that access, and with the database as sparse as it is, why it would be appealing (or useful) beyond the initial encounter is questionable.

In the worst of cases, a digital extension is created but is so wholly dependent on its relationship to the physical exhibition that it is useless, apart from being a potential draw to that exhibition, and is therefore without value after the exhibition concludes (and is of arguably limited value during its run). It has nothing to say on its own and is often left unusable or not hosted at all, referenced only via a broken link on an institutional web page discussing past exhibitions. These lost extensions could be said to be part of a potential “Digital Dark Age,” during which digital content is created en masse but is “subsequently lost due to an inability to preserve the material or a lack of foresight in planning for its preservation” (Reference JeffreyJeffrey 2012: 554). Even early exemplars of digital outreach lack immunity from such losses, as illustrated by Carol McDavid's (Reference McDavid1998) seminal Levi Jordan Plantation site (Figure 4), wherein only three external resource links, out of 16, still function.

FIGURE 4. Carol McDavid's Levi Jordan Plantation website, a seminal example of the internet as an extension of heritage and museology content, still hosted and available though most external links are inoperable due to link rot.

WHAT IS THE TAKEAWAY?

The push toward the increasing use of digital resources in heritage and museology extensions is typically rooted in the best of intentions to democratize the process of heritage engagement and alleviate the pressures of class structures that restrict museum attendance. How successful it has been in this regard, however, remains open to debate (McDavid 2004). As the Interface Experience Web presence illustrates, the connectivity potential of technology has only grown over the past 40 years and is realized materially in the objects that we surround ourselves with and bind ourselves to. To ignore the importance of digital resources in compiling, promoting, and providing heritage and museology outreach would be to intentionally ignore the reality of the modern experience. Part of this appears to be due to audience and a failure to consider who the digital audience is and how they consume digital experiences (Schweibenz Reference Schweibenz2004). I would also point to technological wariness and a fear of utilizing technology outside of the accepted physical methods of heritage dissemination: the untouchable glass-cased object, the textual caption, and the predetermined route of access. Budgeting too is a conditioning factor, including a usual funding structure that privileges the immediate production of heritage output as product over long-term investment in continued relationships and interaction.

Looking at the Interface Experience Web presence is looking at a snapshot of where digital heritage outputs were in 2014. This, in reality, is not appreciably different from where they are in 2018. We are beginning to see our first digital outputs as distant enough to be considered as digital heritage on their own, but we have yet to learn, as practitioners, from that heritage to make changes in our outputs going forward. It is the attitude of complacency—built on the ease of producing digital products—that needs to change, before such poor practice becomes so entrenched disciplinarily that we cannot change it.