Introduction

Is there a discrepancy between the field of International Political Economy (IPE) as we know it from recent debates concerning its role, distinctiveness, and contribution with the actual experience of its practitioners on the ground?Footnote 1 IPE faces a set of dilemmas: intellectually it is needed more than ever to engage real world events but faces constraining institutional imperatives of conformist disciplinary pressures. We have two interrelated objectives related to this: (1) to assess the extent to which the patterns in recent interventions are replicated when you ask those who self-identify as IPE scholars in the UK, and (2) to appraise survey data on the reproduction of a particular community of practice within the field as it evolves intellectually and institutionally in a period of increasing managerialism. Rather than imposing our interpretation of IPE through publications, citation practices, conference attendance, or textbook content as recent interventions have, the article asks how scholars see themselves within IPE to relate their ‘real’ lived experience of teaching and research in IPE in UK universities.

The article offers two important contributions. The first, to report new empirical data on IPE as a ‘field of inquiry’ in UK universities. Longer term, our aspiration is to establish a regular survey of UK IPE scholars, so the article is both an initial statement based on our first survey, as well as a call to colleagues to contribute to the next iteration of the survey of self-identifying IPE academics working in UK universities. The second is to develop a critical intervention on the indisciplined and disorganised nature of IPE as a field of inquiry in the UK. By indisciplined we mean the widely acknowledged and long-standing fertile intellectual advantages of IPE's ‘open range’, unlimited intellectual borders, and transgressive enquiry.Footnote 2 One implication of this is an organisational and institutional disadvantage for IPE as an academic subject distinct from other social sciences.

Two points of clarification are worth noting at the outset. First, we use the phrase, IPE scholars in UK universities where possible to distinguish from the so-called ‘British School’, hesitant to bring such a school further into existence by performatively reinforcing disciplinary caricatures.Footnote 3 The caricatures have often polarised debate and such narratives matter because they have been repeated so frequently that we face the problem of being socialised into accepting caricature as metatheory. In contrast, Leonard Seabrooke and Kevin L. Young reveal how intellectual clustering is inculcated in IPE. They reaffirm a fuzziness of both the intellectual and personal content of defining IPE in terms of two schools by capturing

published articles but also books, and … patterns of intellectual clustering that are not visible elsewhere … [analysing] trends not only in published scholarship but also in teaching (through analysis of IPE syllabi) and through organs of professional socialization such as conference participation.Footnote 4

This challenges the idea of two discrete schools and instead reveals the organisational niches occupied by scholars.Footnote 5 We recognise Seabrooke and Young's entreaty to think beyond these dualisms, and set out to probe one of their niches by asking the members of that niche about their lived experience of working in that niche.

Second, throughout, we also avoid labelling IPE as a ‘discipline’. Our reason for this flows from the main argument in the article: that when looked at from the self-perceptions of IPE scholars in UK universities, IPE looks like an indisciplined field of inquiry that benefits intellectually from that indiscipline but that also faces significant institutional risks associated with the lack of formal disciplinary status that selects and elevates some ideas and their proponents. Instead, we use the term ‘field', emphasising the link into the sociology of knowledge production and dissemination as institutionalised social practice rather than the status conferred by the notion of discipline.Footnote 6 Where we do use the terminology of discipline from this point onwards, is to note the taken-for-granted institutionalised context of knowledge production where ‘what is essential goes without saying because it comes without saying.’Footnote 7 We conclude that indiscipline is a double-edged sword, offering the intellectual freedoms of the ‘open range’ at the same time as configuring institutional vulnerabilities. This core finding offers a novel baseline from which to assess the development of what we will term from this point onwards, the field in the future and potentially make international and regional comparisons. We recognise the limitations of the data for developing the discussion, and style the contribution as an intervention to stimulate further debate.

The argument unfolds across five sections. The first draws out the function of an academic field to provide a reflexive account of the evolution of IPE. Section two then offers a necessarily truncated discussion of that evolution from the emergence of a self-conscious field after the collapse of the Bretton Woods regime, to the implications of the trans-Atlantic debate and more recent interventions. Section three presents the empirical data from our survey and some initial reflections on ethical issues raised by the data. It answers the simple question of: what does IPE in UK universities look like, if you ask its self-identifying practitioners? Section four draws out a series of thematic implications from this data, relating the findings from our survey to the wider debates in IPE. The fifth section poses a number of open-ended questions about the sustainability of IPE into the future.

1. IPE as a field of inquiry

Academic ‘disciplines’ construct boundaries, identify core problematics, specify what constitutes data as opposed to knowledge, they establish a place for critique and the distinction between what is regarded as orthodox and, by extension, that regarded as heterodox, while conveying intellectual histories. Discursive framings have ‘textual, theoretical and political effects’.Footnote 8 These discourses matter, as Lucian M. Ashworth illustrates: ‘one of the most effective ways of disciplining a discipline is to control the historical narratives that lay out the nature and origins of a field of study.’Footnote 9 The gatekeepers of IPE ‘remind those who pray for admittance to the temple that only those who abide by the established rules will gain access’.Footnote 10 There are several well-known accounts of the emergence of IPE as a field of inquiry. We therefore situate our approach in relation, and in distinction to several recent attempts to define the intellectual terrain of IPE.

The most well-known attempt to define the terms of IPE in recent years was Benjamin J. Cohen's account of an apparent transatlantic divide between a positivist, empiricist, and policy-focused American IPE, and a more theoretically open and ‘critical’ British IPE focused on conceptual questions of emancipation. Cohen's account also comes with an ‘origin story’ where the ‘real world’ tumult of the late 1960s and early 1970s prompted an heroic ‘Magnificent Seven’ to fill the void between International Relations and International Economics. Five of these seven launched the American School while Robert Cox and Susan Strange's more critical stance led to the emergence of the British School. Cohen's intervention was certainly effective at evincing responses, many that rejected the binary distinction between schools, objected to the caricatured nature of the framings, and we might add to the imposition of a ‘disciplinary’ narrative.Footnote 11

One alternative response to the imposition of such disciplining is to undertake empirical enquiry offering a systematic method to define the terrain. Just such an approach has arisen recently from two researchers who straddle Cohen's divide. Seabrooke and Young use a sophisticated network analysis parsing data on publishing, teaching, and conference attendance to map the terrain of IPE scholarship. They find that IPE is highly pluralistic with multiple niches of shared research agendas, but in terms of teaching there is a ‘reduction to polarity’ in binary scholarly reproduction processes proximate to Cohen's characterisation of an American and British school, or a ‘quantitative vs. qualitative divide [that] does not dominate the world of publications, but it certainly is present in the classroom’.Footnote 12

A recent similar approach taken by Ben Clift, Peter Marcus Kristensen, and Ben Rosamond reinforced a critique of IPE ‘origin stories’ with a review of IPE textbook narratives and then citation analysis based on published research in two key journals.Footnote 13 Their account both resonates with and diverges from Seabrooke and Young. They uncover a degree of consensus around the reduction to polarity teaching discourse found in IPE textbooks and some evidence to support the Magnificent Seven analysis. However, they also advance a number of additional claims including a close relation between Comparative Political Economy and International Political Economy problematising the 1970s origin story, that output in the two key journals has become less diverse and less supportive of critical (especially Marxist) scholarship over time, and they demonstrate important omissions in the citation practices of authors published in these journals, in relation to feminist and gender scholarship.

IPE has adumbrated a set of now traditional core problematics such as trade, finance, (US) hegemony, multinational corporations, north-south relations, and globalisation. Given Clift et al.'s findings, a recent shared Special Issue of both RIPE and NPE also discussed the relative paucity in IPE scholarship that reflected the significance of coloniality and patriarchy in the field.Footnote 14 These omissions and silences are concerns that IPE scholars have previously visited.Footnote 15 It is not as if IPE has failed in the past to focus on these issues as the contributors to these Special Issues have repeatedly immersed themselves in such topics. Yet, as Heloise Weber reminds us, ‘It is … less than clear, for instance, why important issues … were completely absent’.Footnote 16 It is not as if gender inequalities and patriarchy did not exist before Cynthia Enloe or Spike Peterson offered a language in which to theorise them, nor racial categories before Robbie Shilliam or Lisa Tilley articulated their absence.Footnote 17 Rather it is that such discussions have not taken off in terms of a critical mass of scholarship.

In the various efforts to define the terrain of IPE there is relatively little consideration of the way that the institutional structures exogenous but contextual to the intellectual process help to shape the field. Here the distinction between field and ‘discipline’ becomes clearer. In some cases fields of inquiry become recognised in more formal institutionalised structures as subjects or ‘disciplines’, which are then regulated by committees, producing statements of appropriate subject content and methods of enquiry. In the UK, performance management systems focus around a series of university and subject level metrics that construct league tables of increasing importance as they are gradually attached to funding streams and used to develop a quasi-market for research funding and, importantly in the contemporary period, student numbers. Though what survives of this in a post-pandemic future will be open to debate. Nonetheless, any story of the evolution of IPE must also embed its proponents within the broader institutional arrangements of UK Higher Education (UK HE).

These arrangements convey status, and link intellectual inquiry to accounting systems and funding models. In the context of the UK HE system ‘disciplines’ receive different forms of institutional recognition. These include being granted codes accounting for staff and student numbers, for recording performance in terms of student employability and satisfaction with their course, for reporting progression and dropout rates. Some of this data is drawn together in assessments of performance in teaching like the Teaching Excellence Framework, and institutions use that data to guide staffing decisions and considerations of what courses to introduce, expand, or contract. While the majority of funding for teaching comes from students themselves paying £9,250 a year (and considerably more for international students) there are government funded uplifts for courses considered of significance or involving higher costs, such as lab-based science subjects. Some social sciences – notably Psychology – attract such uplifts.

‘Disciplines’ are also recognised in terms of research and the regular assessments of performance that result in significant allocations of public money for research. The Research Excellence Framework (REF) and its predecessor the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) are used to divide available public funding by institution so that each receives an allocation of annual funding for particular subjects. Institutionalised ‘disciplines’ in this sense count; they are used to organise the allocation of resources. Formal status helps in the reproduction of an intellectual field of inquiry.Footnote 18 As a significant aside it is notable that the emergence of IPE occurred at about the same time as governments strove to increase the regulation of academic inquiry through disciplinary structures and, in particular, to focus the social sciences on questions of importance to the economy, the increasing commercialisation of HE and the wider politics of performance management.Footnote 19

All empirical research has strengths and weaknesses and methodological pluralism often helps to produce a more comprehensive picture. While network and citation analysis certainly throws up interesting patterns and findings, they are clearly not immune to common research problems. For example, while the key interventions we noted above are admirably rigorous in their approach, they cannot completely overcome the selection challenges that bound their enquiry. An alternative approach we utilise below is not so much in competition with these enquiries but instead compliments them. First, we sought to overcome some of the selection issues in these definitional reviews, and the danger of contributing to an intellectual disciplining or border construction process. Second, we sought to consider both institutional and intellectual currents and, at least to some extent, the interaction between the two. The method we chose to achieve this was simple; we explore that field of those who self-identity as IPE scholars (rather than having that designation assigned) in UK universities, by asking them about their working lives.

The stories we tell about ourselves are vital narratives, as ‘control over knowledge about the disciplinary past is one of the primary means through which particular moves in the disciplinary present are justified and legitimized.’Footnote 20 How might we move beyond a ‘debate about a debate’, abstracted from the lived experiences rather than relying on published outputs, sociological reconstructions, interpreting citation practices, or what gets taught as ‘the canon’?Footnote 21 We ask the occupants of that niche to tell us about themselves and what constitutes their ‘real’ lived experience of teaching and research in IPE in UK universities.

2. The emergence of IPE as a self-conscious field

Part of the problem for IPE in constituting its own status is precisely because of the often-repeated claims of wide-scoped and porous disciplinary boundaries.Footnote 22 We focus in this section on the intellectual opportunities that this offers and return to the institutional problems of IPE seeping into other academic ‘disciplines’ below. There are clearly key issues and debates that constitute IPE as a field. Similarly there are wide ranging epistemological variations of what constitutes knowledge and understanding in IPE. There is a place for critical scholarship, alongside ‘disciplinary’ histories. We need to remain cognisant of the way that certain powerful myths structure the naturalisation of the field and our engagement both internally and externally. How we narrate our histories matters, and discursive framings have ‘textual, theoretical and political effects’.Footnote 23 Or as Leszek Kolakowski put it, ‘we learn history not in order to know how to behave or how to succeed, but to know who we are.’Footnote 24 What appears to be the intellectual and institutional crossroads IPE finds itself at might be an expedient starting point for rethinking questions of who ‘we’ are, beyond existing analysis of citations, networks, or reading lists. Instead, we ask the scholars who self-identify as IPE themselves to discuss their ‘disciplinary’ or, indeed non-disciplinary status and explain this ambiguous status.

No field exists in a vacuum. One history that we tell about ourselves is that since the 1970s US policy orientation has set the agenda as the foundation of that self-conscious field called IPE. This is the history that the most recent debate has elected to reinforce.Footnote 25 IPE emerges from US policy and academic circles following the breakdown of Bretton Woods in the 1970s,Footnote 26 the emergence of yet another round of the US decline debate,Footnote 27 and the emergence of US policy concerns related to interdependence and multipolarity,Footnote 28 propagating the foundational texts of IPE as a self-conscious ‘discipline’ distinct from IR. Such fundamental changes precipitated a decisive shift in the balance of economic power in the international economy. US policymakers and scholars grew fearful of the growing interdependence of national economies and the perceived threat to sovereign governments to stay in control of economic affairs. This was manifested in the theory of complex interdependence and the emergence of transnationalism,Footnote 29 concerns with the impact of ‘domestic structures’ on world economy alongside explorations of hegemonic stability and Regime Theory.Footnote 30 This long since naturalised retelling of history is that IPE emerged in the 1970s as an amplification of IR, and established a field neither solely IR nor international economics that Susan Strange, supposed ironically referred to as concerning ‘states and markets’ and countless introductory textbooks and histories of the field have reproduced.Footnote 31

Contrast this with an alternative story where IPE frames itself as historically sensitive and self-aware. This has often been a rather superficial engagement, as Matthew Watson's astute excavations of the classical political economy roots in IPE reveal, mapping foundational thinkers onto the existing trichotomous paradigms.Footnote 32 It is of little surprise that deeper engagement emerged after the so-called global financial crisis.Footnote 33 Rejecting the narrative of IPE emerging in the 1970s IPE scholars became deeply concerned with its own longue duree historiography driven by efforts to understand the implications of the separation of politics and economics and the disappearance of political economy that reappears at points of great crisis such as the challenge of reconstructing the international economy after two world wars, the Great Depression, the global financial crisis, and Covid. The distinction between a self-conscious IPE and an historical IPE remains and the 1970s intellectual scaffolding has been dragged into the debate around Cohen's transatlantic divide. Our aim here is not to refight this debate; rather we restate the positions to offer context for the survey. Obviously, we do not accept that the territorial terminology is tied to any particular approach to IPE; rather that this acts as caricature of the epistemological, ontological, and methodological commitments of said approaches.

For US trained scholars IPE is centred on a particular reading of the scientific model committed to positivism and empiricism. The main problematic remains centred on the state, particularly questions related to how states behave. It is founded on a logical, reductionist, deductive epistemology that given its heritage in US IR seeks to offer parsimonious theorising to develop generalisable laws and predictions. This often appears in the form of certain factors of analysis and their measurement through statistical analysis of empirical data. IPE is taught as one subdisciplinary component of IR in the US, which is already considered a subdiscipline of Political Science.Footnote 34 This offers some explanation for the dominant norms of quantitative methods that have come to dominate in this particular school. With the increasing dominance of open economy politics in US scholarship, IPE has ‘moved away from the traditional “big questions” toward more micro-approaches that successfully integrated key insights of both comparative political economy and IPE’.Footnote 35 This contrasts with the so-called British School, often explained as commencing with Strange's entreaty to ask qui bono. An openness to pluralist approaches, interdisciplinary links across other social sciences and humanities confects an emancipatory IPE that still subscribes to grand visions of societal transformation and development with the state just one of many actors.Footnote 36 This germinated in Strange's 1970 article and a year later the establishment of the International Political Economy working group (IPEG). Our concern for IPE is the danger of a narrowing of the intellectual terrain of scholarship, we suggest, akin to the way that a particular method, as well as a rejection of that method, has come to colonise and fundamentally split Economics, one of the fields cognate to IPE, inducing all manner of institutional problems for heterodox economists.Footnote 37

3. Data and methods

Our stylised reading of the contours of the intellectual terrain of IPE clarifies how and where our intervention is situated in contributing to existing debates. In this section, we turn to the empirical data that provides the basis of our analysis. The article draws on data from a survey of academics in UK universities self-identifying as working in IPE. It was distributed through a number of key online IPE networks (the IPEG email list and Facebook page, CPE-RN, and the Occupy IR/IPE Facebook page). Additionally, we asked participants to encourage snowballing the survey and galvanise others by forwarding the survey to their personal networks of those who fitted the criteria of working in IPE in a UK university. We did not distribute the survey through networks where the vast majority of the membership would be based outside UK universities, (such as the International Studies Association IPE email list). While this may have marginally increased the response rate, we were interested specifically in self-identifying IPE scholars in UK universities and UK-based networks were deemed the most appropriate method of circulation. Moreover, while we could have attempted selection of IPE scholars by invite, this would have relied on our own determination of who counted as an IPE scholar, rather than the respondents themselves, replicating some of our aforementioned concerns with the Seabrooke and Young method. The survey was in field for three months between September and November 2016 and received 62 completed responses.

Some injunctions reflecting on the ethical issues raised by the study data are necessary at this point. Both authors are themselves embedded in UK IPE. Given the relatively small (and as we claim later, even smaller) IPE community in the UK we were concerned that the sorts of data we would collect could easily reveal the identities of individuals and this would hinder completion rates and present a dilemma in reporting. We contracted a separate commercial survey firm with experience of undertaking often very large-scale surveys. They conducted the survey and separated aspects of the data that they reported to us. For example, the data provided included in one block individual responses to most of the questions we asked but separated from names, contact details, institutional detail and some other aspects of the data that could have identified individuals (such as institution they studied at, supervisor). This data was provided because it helped to shape our analysis but in a disaggregated fashion. We are unable to link pieces of data related to individual identity with answers to other questions. For example, we could not say how a single respondent supervised by a particular individual felt about their working conditions or compare working conditions in one institution against another. Survey respondents had an initial information sheet that explained the separation of data and the purpose we would use the information provided.Footnote 38 The survey tool was approved by both institutional research ethics committees. Funding was received from one of the institutions to pay for the administration costs of the survey and for a free prize draw that acted as an incentive for survey completion. The name of the winner was publicised with their explicit permission.

A second concern relates to the representativeness of the response sample. We were initially disappointed at what appears a rather low response rate. The IPEG list contains more than four hundred email addresses and a response rate of 15 per cent would be problematic for any analysis we might develop.Footnote 39 On reflection though, many of that putative four hundred work outside the UK, one such colleague volunteered a number of times to complete the survey if needed (we resisted that request), many from disciplines that are at best tangential to IPE, and also others whose email addresses are out of date, duplicated, and who may have moved out of active engagement in IPE (retired, moved into administrative or management roles, subject focus shifts, etc.). Over the last twenty years the IPEG mailing list has predominantly shared information rather than driven intellectual debate. The most important point though for the claims the article makes is the frequent elision of UK IPE and political economy. Care is needed when making claims about IPE in the UK when there is slippage across such distinctions.Footnote 40

In other subjects the institutional apparatus of UK HE might be used to develop an evaluation of representativeness of our sample. All UK universities make an annual return to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), which covers staff and students by subject area. However, there is no subject code for IPE. The closest is ‘Politics’ but clearly not everyone in Politics departments is focused on IPE, and IPE scholars are frequently based across a variety of departments. A search on the University and College Admissions Service (UCAS) reveals that there are 35 institutions in the UK teaching undergraduate and/or postgraduate programmes with a keyword including either IPE or GPE. Few of these actually list a programme with IPE in the title itself (three courses at undergrad in two universities and 17 courses in 14 universities at postgraduate level). Using HESA student number returns at programme title level, we find 15 institutions running thirty postgraduate programmes with 615 students registered to them in 2016–17. At UG level there were four programmes at four universities with a total of 430 students registered to them. There are questions where we do not report the data at all and places where we report the data at high levels of aggregation to avoid analysis the overall numbers cannot support.Footnote 41 The more one looks at such proxies the less problematic our sample size.

The HESA figures and our survey data reinforces our argument around the legitimacy of the existing survey response. We suggest that four hundred includes non-UK scholars, numerous duplicates, and is much closer to the wider political economy community in the UK than those who self-identify specifically as IPE. Perhaps institutional structures in universities find it easier to understand the discipline of political economy in contrast to IPE? We now think that the community of scholars who self-consciously identify as IPE, who are the practitioners of IPE rather than political economy in the UK is somewhere in the region of 100–150. Given that, we are satisfied that a response sample of 62 is sufficient to draw tentative outline conclusions about the nature of the population, even if we cannot be sure of the ‘representativeness’ of the response sample relative to the wider population. As below, the characteristics we were able to observe of the response sample were broadly in line with the staffing of UK politics departments, as documented in institutional disciplinary data. It is certainly not a ‘small’ sample relative to the population, though the absolute size of the sample mitigates against more sophisticated analysis of invariance between subgroups. Where we do draw out invariance, we highlight the statistical limitations involved.

4. Survey findings

The survey data support two key findings: IPE scholars in the UK are indisciplined in that they draw on a wide range of intellectual influences, publish in a wide range of journals and engage in broad ranging debates. This indiscipline extends to pluralistic theoretical leanings, within a broadly ‘critical’ orientation. Indiscipline does not necessarily equal diversity however, either in the identities of IPE scholars themselves or in terms of the nature of their intellectual influences. The data also supports a second headline finding: that indiscipline may have some associated costs. The field of inquiry is relatively small in both the number of staff involved in it and its institutional footprint. This and a perceived lack of prominence, especially at institutional level suggest that indiscipline may lead to a somewhat fragile university profile, and there are also indications that IPE scholars lack confidence in the wider institutional support for the field, in relation to research funding, for instance. An extension of this is that some IPE scholars had concerns about their own working conditions and their security/fairness, though this may be a separate point related to insufficient support for diversity and job security, reflecting gendered and wider inequalities in the UK HE workforce, as recently reported in a Special Issue of Political Studies Review.Footnote 42 Overall, we suggest that the findings can be aligned to two core themes: (1) intellectual indiscipline and (2) the nature and effects of institutional indiscipline.

Intellectual indiscipline

The survey asked a number of questions that helped to unpick the intellectual structure of the field of inquiry occupied by self-identifying scholars of IPE within UK universities. One indicator of a lack of intellectual ‘discipline’ was the disciplinary background of respondents. Answers to these questions revealed a wide range of undergraduate backgrounds and even PhD topic (though 43 per cent were from a Politics background at undergraduate level). Our respondents suggested that their work had been shaped by a wide range of individual influences – with five ‘free' choices to rank the most important individual influences on their research, they identified a total of 130 separate individuals, most of whom received one nomination. The long list provides some indication of the plurality of influences on UK IPE academics. A similar pattern emerges when looking at responses about the journals that respondents read and would consider submitting to with more than ninety journals being identified in both prompted and free text questions. Journals that publish broadly critical scholarship were prominent indicating that it is difficult to unpick a ‘disciplinary’ core undergirding IPE.

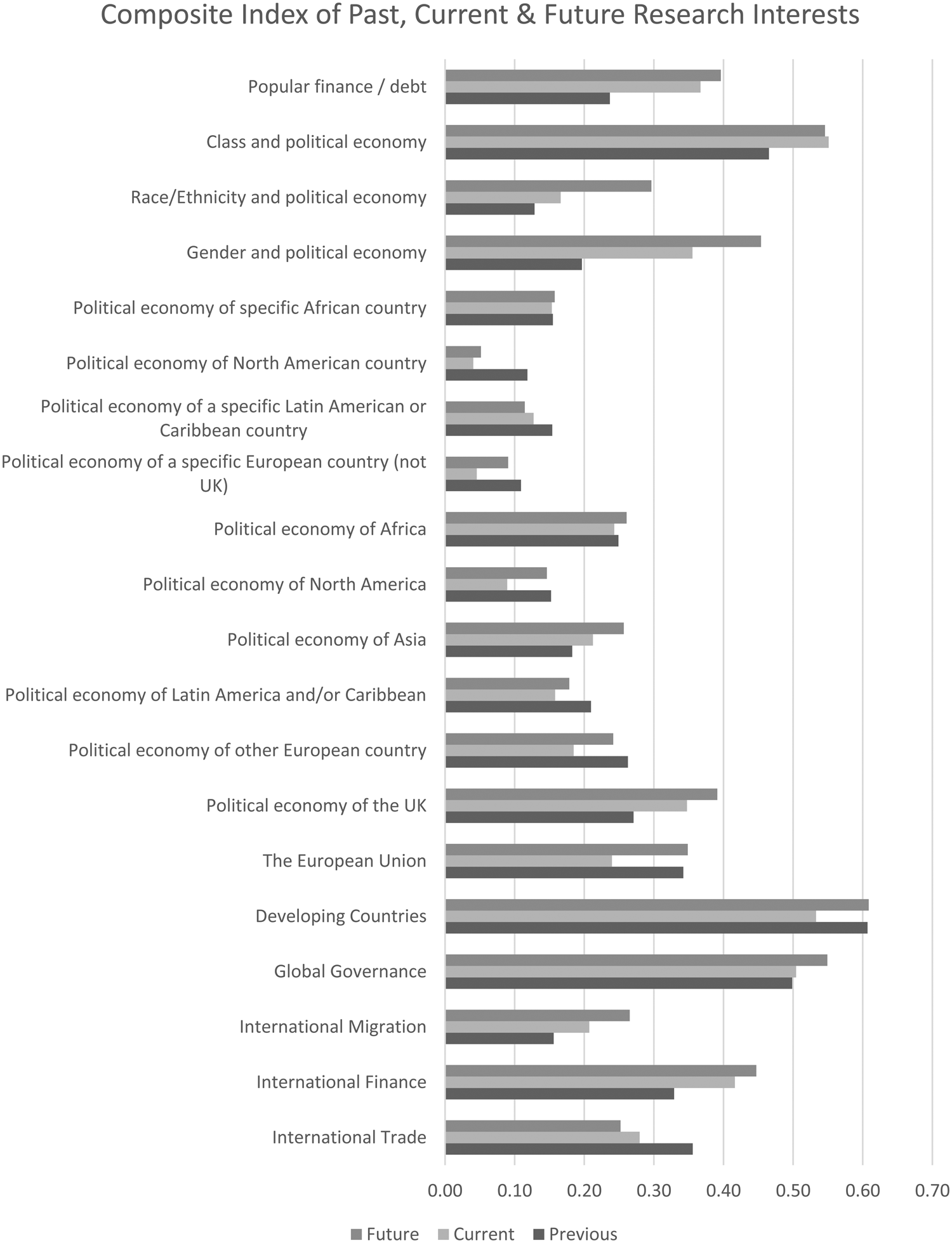

Consideration of primary research interests, or the ‘meat and potatoes’ of IPE scholarship is clearly revealing of the collective trajectory of research in UK IPE, though we feared overstating the case and potentially misleading (see Figure 1).Footnote 43 There are interesting parallels here with Seabrooke and Young's discussion of two clusters of case-led research around global economic governance and international organisations.Footnote 44 The survey data shows ongoing interest among UK-based IPE researchers in topics such as class, developing countries, international finance, debt, and global governance with a quarter or more of those that identified primary research interests selecting these. The data also suggests that these are the main areas for future research interest for UK researchers. Other topics that the survey indicates are of growing interest are gender and race, perhaps an attempt to diversify the subject matter of IPE reflected in recent illumination of our blind spots.Footnote 45

Figure 1. Composite of index of past, current, and future research interests.

Research interests in the UK, international trade, and the EU all show interesting patterns, possibly related to contemporary events. Less than a quarter of respondents’ primary interest is the UK but that represents a growth in interest from researcher's prior interests (in terms of ‘primary’ interests at least). This may reflect the burgeoning interest over recent years in austerity and also the domestic foundations of the global economy; either in the sense of the way that domestic political economy structures contribute to actor-agency at the global scale,Footnote 46 or the literal domestic foundations of the global economy in household structures.Footnote 47 However, we also speculate this might be related to our distinction between IPE and political economy. Colleagues working on the international aspects of the UK political economy may not self-identify as IPE. Both international trade and the EU were previously of more interest but look like they are set to recover some degree of prominence in IPE researchers’ agendas reflecting the impact of the Brexit referendum which immediately preceded the survey fieldwork period, and surely there will be a response from IPE scholars thinking about COVID-19 the next time we run the survey.

Open text responses to questions about research interests revealed broad continuities in interest. Several thematic areas appear, only partly covered by the prompt list. These included topics that could be aggregated to ‘globalisation’, ‘work, global production and production networks’, ‘popular resistance, social movements and anti-capitalism’. Other topics raised tended to be individualised such as history of political thought, energy, conflict, fraud, and ‘the seaside’. No clear collective patterns emerged in terms of change over time as a group of researchers from this data, but it is indicative of the freedom to pursue evolving and interdisciplinary lines of inquiry that might result from indiscipline.Footnote 48

We also asked a number of questions related to theoretical orientation and research focus. Strong associations among respondents existed with Marxist, Gramscian, constructivist, feminist, and poststructuralist theoretical traditions (confirming Kristensen and indicating where Clift et al.'s missing Marxists have been hiding).Footnote 49 The data shows little self-identification of scholars in the UK as realist or liberal. There is the possibility that our survey distribution networks reinforced bias among critical scholars and scholars of different theoretical traditions are engaged with alternative networks. While this might be a function of soliciting responses from particular networks, as we noted in the previous section, it is not clear which additional networks would have helped the sample be more representative without straying beyond scholars who self-identify as IPE practitioners in UK universities. We may have gained additional responses via networks in ‘Economics’ or ‘International Relations’. Though we do not have data to explore this question, if it were the case that the response sample would have been more heterogeneous theoretically and less critical in orientation, this suggests that the label IPE in the UK denotes a specific critical orientation, that is, it is not just members of the field that are disproportionately critical in orientation; rather it is the label and networks associated with it that denote this. This again emphasises the importance for a certain intellectual and institutional mobility across established ‘disciplinary’ borders.

It is also interesting to identify overlaps between the influences of different theoretical traditions to illuminate the ways in which IPE researchers in UK universities combine multiple traditions. The most prominent overlaps were perhaps unsurprisingly between the influence of Marxist and Gramscian perspectives. Just under half of those who identified in some way with Marxism also associated their work with Gramscian theory. Other prominent theoretical associations emerged between Marxism and feminism, constructivism and institutionalism, and between constructivism and neo-Gramscian perspectives. Perhaps a more counter-intuitive overlap was evident between Marxist and institutionalist influences; half of those associating with institutionalism also associated themselves with Marxism. These overlapping responses reinforce assessment of a critical orientation of UK IPE. For example, while institutionalist scholarship can be oriented towards a less critical stance, its combination with constructivist and Marxism among UK IPE scholars suggests otherwise. Again a preference for broadly ‘critical’ theoretical traditions combines with intellectual indiscipline in the willingness to combine theoretical traditions. Our sample of IPE scholars in the UK is not a community of conformists in any sense of the term.

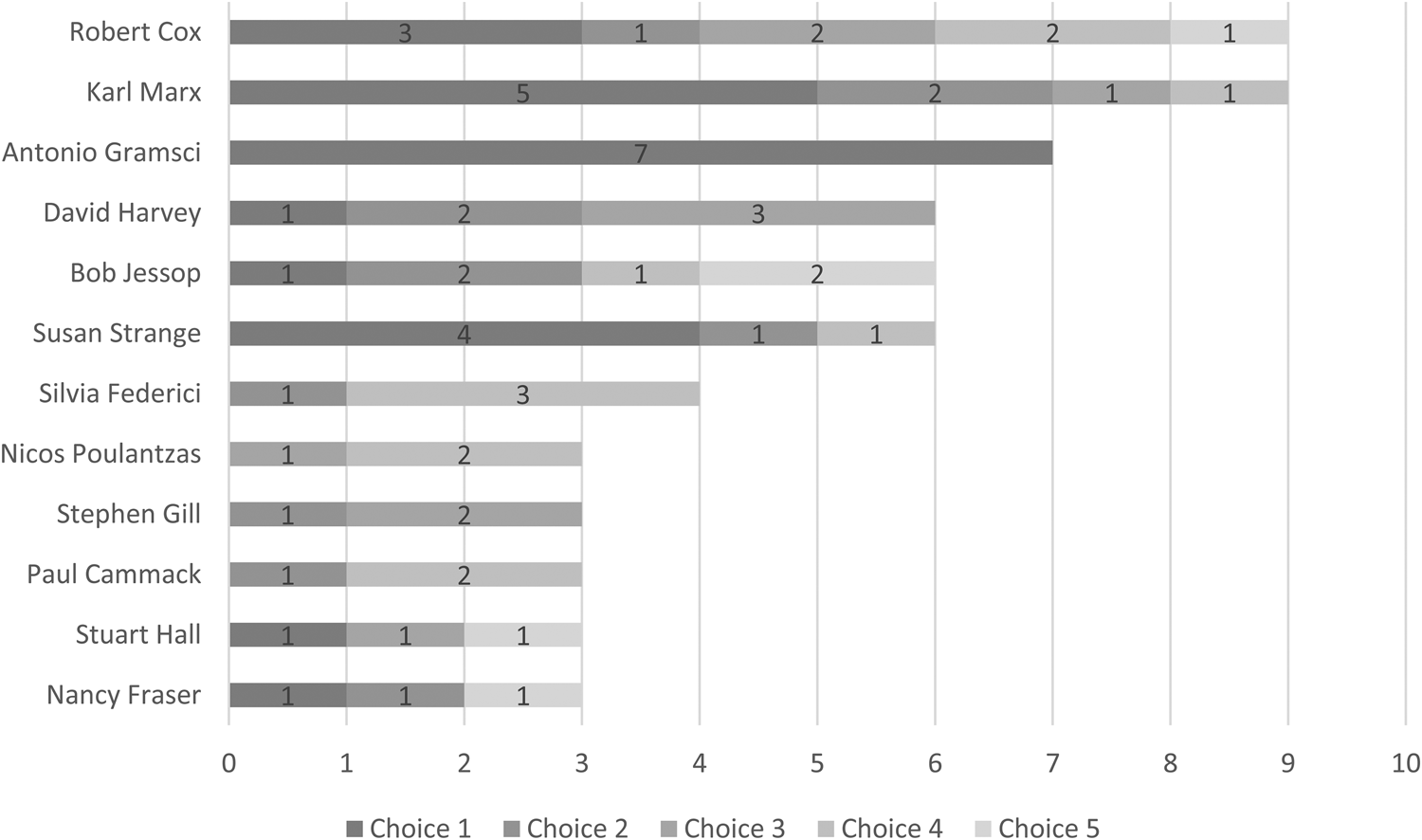

A more complex picture arises if we frame the analysis slightly differently and cast it in terms of respondents’ five choices of intellectual influence. A small number of individuals were identified by multiple respondents. Figure 2 sets out the five most cited influences. Karl Marx and Robert Cox were the most frequently identified across the five selections, while Antonio Gramsci received the most nominations as ‘first choice’ (though the options were not explicitly ranked in the questionnaire format). Prominent feminists are also present. Further indicating either indiscipline, or the inaccuracy of Cohen's origin story for IPE, of his Magnificent Seven, only Cox and Strange show up in this data, again suggesting a lack of field constraint in terms of the positivist leanings of the American roots of the post-Bretton Woods origin story.

Figure 2. Respondents’ major intellectual influences.

However, imputing gender and ethnicity to the authors listed – clearly not an ideal method – is nonetheless revealing about the nature of indiscipline.Footnote 50 Namely, indiscipline does not necessarily indicate diversity. Among the ten most frequently cited intellectual influences (aggregating all five choices), only three were women, against nine men. As far as we can gauge only one of the twelve individuals in the top five ranked positions is/was not of white European/North American ethnicity. In the whole list of 130 individual intellectual influences of our respondents, 27 of the individuals were women, receiving 38 nominations. This compared against 103 men, who received 156 nominations. Given that academics are likely to reproduce the prominence of their own intellectual influences in their research and teaching, this adds weight to the recent self-critical exhortations among IPE scholars based in UK universities to consider important ‘blind spots’ in our scholarship, and the multiple and rich directions of a wide scoped roving field of inquiry.Footnote 51

This lack of diversity is somewhat underlined by the identity of respondents themselves (see Table 1). This shows that women have a slightly higher representation (37 per cent) but that the ethnicity profile is very similar (79 per cent white) to Politics departments more generally. The nationality profile is also similar with (62 per cent being of UK nationality in Politics departments) but slightly more other-EU nationals in our response sample than more broadly (15 per cent). Overall then our response sample is no more diverse than Politics departments nationally, which are already identified as lacking diversity.Footnote 52

Table 1. Summary of respondents by equalities profile.

The nature and effects of a lack of institutional discipline

In contextualising the data we have already proposed that the reality of IPE in the UK is a relatively small endeavour that lacks institutional status in terms of formal nomenclature such as a HESA subject code, Unit of Assessment in the REF, or independent recognition in the TEF or institutional status such as departmental structures. There were several themes in the survey data that illustrate the nature and consequences of being a field of study that lacks this institutional ‘disciplinary’ recognition.

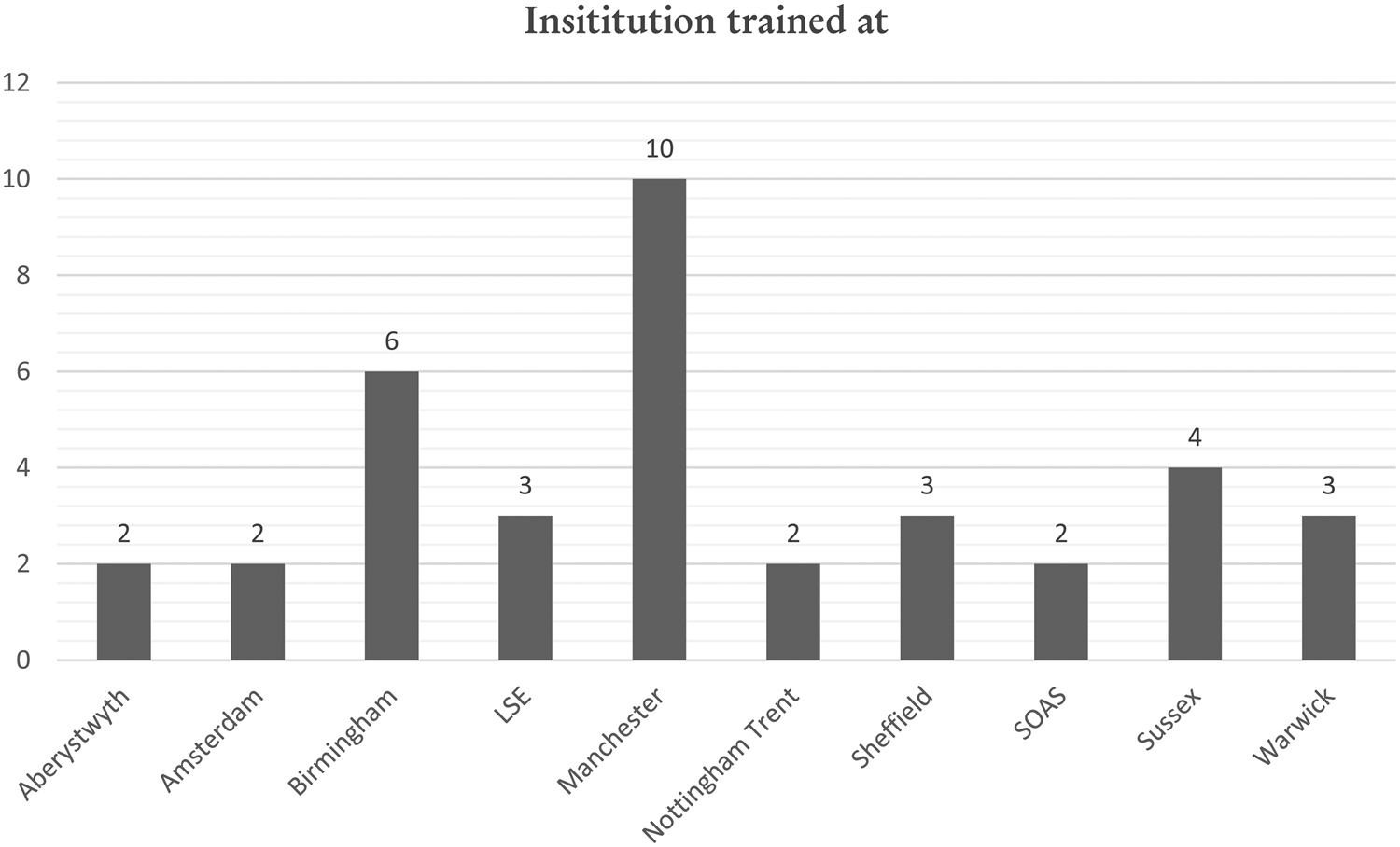

The institutional footprint of the field is narrow. Figure 3 shows the primary institutions where IPE scholars completed their PhD. We list only those institutions that were included at least twice. We can also look backwards in career development terms and see that the vast majority (84 per cent) of UK-based IPE academics in our sample were trained in the UK, even where they had different nationalities, and in a relatively limited number of institutions; mostly ‘old’ pre-1992 universities and where a handful stand out as being the most important training institutions for the current workforce (Birmingham, LSE, Manchester, Sheffield, Sussex, and Warwick). This suggests that claims about the intellectual diversity, plurality, and openness of the subject should be set against the indicators that inculcate a degree of homogeneity and narrowness in the reproduction of IPE.

Figure 3. Institution trained at.

The visibility of the six institutions here offers some interesting points for reflection. As we have implied through the preceding stages of the article there are a number of institutions known for doing political economy rather than IPE. LSE and Sussex are the only institutions with departments that carry the international in the departmental name specifically. One curious absence from the data is Kings, one of the largest groups of IPE scholars in the UK but also one that offers courses that could be identified as IPE across a number of different institutional structures including a department of Political Economy as well as European and International Studies with its IPE MA pathways, and IPE research grouping. This absence reinforces our point regarding the institutional elision of political economy and IPE. Of the core institutions associated with the reproduction of IPE as a field, Sheffield (SPERI), Manchester (PEC), and Warwick (CSGR) also have long-standing strong, multidisciplinary, and institutionally supported political economy research groups.

The UCAS data combined with our response data suggests a relatively small field of study, lacking in critical mass either within or between institutions when judged in volume of staff and students, relative to other social sciences. Among our sample, self-selecting those who identify as in IPE networks motivated to take a survey badged and explained as being about teaching and researching IPE, 23 per cent reported that IPE is not their main field. Respondents also suggested that they felt the subject lacked institutional support with only 50 per cent saying the subject was seen as important in their home department, and this falling to 30 per cent at faculty and 16 per cent at institutional level (see Table 1).

Even where respondents felt that IPE was taken seriously in their institution, several indicated the erosion over time with a shift towards security studies as the ‘disciplinary’ representation of the international in politics departments. Several respondents noted that they were the only member of staff focusing on IPE or were among a very small group of staff, which reinforces our sense of the distinction between I and PE. Alongside a lack of undergraduate programmes with relatively small numbers of taught postgraduate and PhD students, this contributed to indications that IPE was unimportant as a subject outside of lower-level institutional structures (that is, departments). Some respondents indicated how even where other IPE colleagues were employed within the university they were spread widely across departments and rarely worked collaboratively. Our suspicion then, reinforced, if not entirely ‘proved’ by the data, is that beyond the big six IPE training institutions a disparate workforce is stretched thinly across many institutions lacking institutional critical mass for teaching or research when compared to other cognate fields like Criminology and heterodox Economics as we noted above.

The juxtaposition with Criminology is particularly apposite. Criminology is also an interdisciplinary field that developed out of Law and Sociology and Psychology with a similarly broad field providing refuge for scholars at one end of the spectrum, who explain crime as a problem to be controlled by punitive state responses, to those who emphasise the uneven social and power relations that legitimise certain behaviours and delegitimise others. That should resonate with IPE scholars, yet while IPE has eschewed disciplinary organisation, Criminology has pursued it. The British Society of Criminology has organised and been active in distancing from the disciplines (in both senses) of Law and Sociology. They have developed a subject benchmark and the REF consultation recognised the clamour among criminologists for a separate Unit of Assessment (UoA). Whatever the outcomes of REF2021 and the shape of REF2028 take, Criminology will likely emerge further reinforced as a ‘discipline’ with all the resources and recognition crucial in the pursuit of funding and impact for self-reproduction.Footnote 53

Another indication of a lack of institutional weight might travel through sector-wide initiatives such as the REF and resulting quality profile and volume metric for distributing research funding between subjects and institutions. IPE does not have a REF UoA and scholars are therefore returned to a wide range of cognate subjects including Business and Management, Law, Politics and International Studies, Sociology, and Social Policy. We asked respondents to what extent they had been affected by institutional pressures such as the REF. More than 67 per cent reported that they had been affected ‘greatly’ or ‘somewhat’ by the REF, with a quarter saying it had not impacted them at all. The main impacts cited were changing where scholars sought to publish (more than 42 per cent), with demotivation experienced by a quarter of those that answered the question and just over a fifth reporting positive effects. Less than 6 per cent of UK-based IPE scholars reported that they had changed their research focus empirically, theoretically, or methodologically because of the REF. This may also link to an important apparent contradiction. In the survey, IPE scholars have responded to institutional pressures by partly ignoring, partly resisting them. We suspect that the porosity of disciplinary boundaries reappears as an important factor here. One potential impact that might help to explain both the small footprint of the IPE field of inquiry and also the ambivalence of some self-identifying IPE scholars towards labelling themselves as such may be that disciplining structures such as the REF force researchers to identify with other ‘disciplines' in order to gain institutional recognition and reward for their work.Footnote 54

One further consequence of a lack of ‘disciplinary’ structures might be engagement with sector-wide support institutions. Our survey data suggests that IPE researchers are relatively unenthusiastic in applying for research funding and when they do this tends to be from only a small number of sources. Fifty per cent of our respondents have applied for funding from the ESRC, and Leverhulme/British Academy are the only others attracting applications from a sizeable proportion of our respondents (30 per cent). For most other funders, limited numbers of IPE scholars had applied. Similar patterns were observed for future intentions to apply. In particular very small numbers of IPE scholars had either applied in the past or were considering applying for funding from international foundations, charities, the EU, and UK government. Given the theoretical orientations we might well anticipate some of the ‘self-censoring’ reasons for this. However, given the reported research interests of IPE scholars and their reported concerns about institutional support, it may well be that failure to engage with funders is a significant problem for the institutional status of the field. The formal institutional scaffolding of a discipline matters when other cognate fields are funding similar research to IPE, in development studies and geography for example. That said, a lack of institutional embedding is unlikely to make those concerns any easier.

Despite this, and again representing a preference for indiscipline over organisation, relatively few respondents expressed enthusiasm for professional associations. Fewer than 15 per cent of those that answered the question suggested that they wanted ‘professional recognition of taught awards’, ‘regulation of staff-student ratios’, or ‘academic training’. The most popular additional function for professional associations was PhD training, but that still failed to garner support from a quarter of those who answered the question. There is no single professional association explicitly associated with IPE. Respondents to our survey belonged to a wide array of such organisations. BISA was the most prominent of these; but with only 25 per cent of respondents’ members, its coverage was far from comprehensive. Only around 10 per cent of respondents were members of the PSA. We speculate that would be much higher among political economists given PSA has a British and Comparative Political Economy specialist group. Otherwise, respondents belonged to a wide range of international organisations (that is, with less interest or purchase in engaging with detailed aspects of UK HE policy and institutional environment or career structures). Even in the face of complaints about working conditions, concerns about institutional support and a clear lack of experience in seeking external support for their work, IPE researchers appear not to want a more institutionalised discipline with no clear vehicle to achieve this even if they did, reliant instead on existing levels of engagement with BISA and to a lesser extent, the PSA, as well as finding more hospitable intellectual homes in international, and therefore less institutionally or sectorally influential organisations at UK level, like CPE-RN and IIPPE.

In this section we have discussed the survey data. There is a tension evident between a relatively narrow intellectual position, a porous set of boundaries with other fields, and interaction with institutional constraints. In the next section, the article moves on from the data and reframes the discussion by roblematizing how IPE might develop.

5. Implications for the future of IPE

The motivation for this article was a sense of unease that, at least anecdotally at conferences, and in the pages of field reflective pieces, IPE has been a ‘discipline’ if not in crisis, then at least deeply concerned with ambiguities over its identity and status. Our intervention addresses whether the field of inquiry generated through the literature or networks tells the same story about IPE as those scholars who identify as the practitioners of IPE. The data, although far from conclusive as we discussed above, allow us to frame a preliminary account of the challenges facing IPE scholars in UK universities. As throughout, we split these into two broad framings, intellectual and institutional, for ease of engagement and analytical purposes only, fully acknowledging issues that such parsimonious distinctions generate.

If we want a neat message to read into the survey data, it is the benefits of an indisciplined intellectual project set against the institutional rewards for formal disciplinary structures. IPE in the UK is situated among other social sciences but with no agreed and distinct set of theories, epistemology and methodology. A healthy situation perhaps, but one that lacks institutional power. The parallels with Economics are an instructive warning. Drawing on Sheila C. Dow's critique of ‘anything goes’ as antithetical to quality control,Footnote 55 Geoffrey M. Hodgson identifies how heterodox economists identify as a community but fail to agree what heterodoxy means.Footnote 56 The development of heterodoxy alongside mainstream Economics inculcates problems when attempting dialogue between competing visions of what constitutes a ‘discipline’. As Hodgson notes, ‘disciplines work as ensembles of social institutions … disciplines are organised systems of power. However imperfectly, these systems control quality and create incentives for enduring participation and engagement.’Footnote 57 Our data suggests that UK IPE practitioners are committed to challenging inequities in this world, using non-positivist methods and a broad sweep of critical theoretical perspectives in the face of institutionalising pressures on funding, career development, and performance management imperatives.

A significant challenge for IPE in UK universities is the absence of the formal disciplinary and institutional professionalisation structures that shape a field.Footnote 58 UK IPE is not represented by any single professional association, and falls between institutional and disciplinary representatives. UK IPE scholars exist in a number of competing as well as complementary institutional spaces. Perhaps IPE scholars do not want to accommodate what it means to become a stable academic ‘discipline’?Footnote 59 If we did not already know, wide-ranging epistemological and ontological positions have practical institutional as well as productive intellectual outcomes.

Immediate concerns from these questions include IPE's formal absence from the REF, a lack of representation in (HESA) subject codes used to generate data to assess institutional performance and make funding decisions in relation to research and teaching or monitor the distribution of resources and equalities profiles of both staff and students. How would we know whether IPE is well supported in material terms compared to other fields? How would we assess the relative quality or robustness of IPE scholarship or its impact and how could we understand the subject's reproduction into the future unless such criteria are in place? Our survey exhibits similar self-identification issues for IPE. Universities are also subject to the same internal interest group politics as any other institution. Previous debates have mostly focused on the internal dynamics of the field, however we need to be cognisant of the external pressures brought to bear on the opportunities for differentiation of a ‘discipline’, such as the resources that enable expansion.Footnote 60 Reproduction of a field as small as IPE depends on a whole series of micro-decisions to award this PhD studentship over that one, to appoint this job candidate not the other, to promote one lecturer rather than another, to create professorial leadership positions in particular subjects, and to cultivate student populations in some areas but not others. Given our survey indicates a relatively narrow institutional footprint for IPE, the low external visibility means that for all its intellectual potential, UK IPE is exceptionally vulnerable to just a small number of these micro-decisions in relatively few institutions with calamitous effect.

Conclusions

This article reported a first iteration of data from what we hope will be an ongoing survey of IPE scholars working in UK universities. We used this material as an intervention in existing debates about the nature of IPE as a ‘discipline’ or as we preferred a field. We did this by reconstructing two competing histories of the ‘discipline’, engaged with existing analyses based primarily on citation data and network analysis and then brought these into dialogue with our data analysing those who self-identify as IPE practitioners in UK universities. We developed a number of points of argument. Do the existing field literature and workforce tell the same story? Partially, yes. The survey data does reaffirm the idea of a particular critical orientation to IPE as practiced in UK institutions.Footnote 61

What is perhaps not so obvious in contrast to previous discussions of IPE as an academic field that frame an interpretation through analysis of networks, publications, citation practices, textbook content, or course reading lists are two issues. First, whether we like it or not, academic fields are defined in part through their engagement with the broader institutions of UK HE, sometimes in alignment with it and sometimes in opposition to it. It may be that the responses of IPE scholars to such developments is at least partly behind the absence of coherent institutional development in the UK. The survey data suggests that IPE scholars have an ambivalent relationship with the structures of power in UK HE and that this to some extent shapes the field, even just by the absence of a push for such structures.

Second, and relatedly, despite the intellectual liveliness and responsiveness of UK IPE, it is a relatively small endeavour often subsumed into political economy or IR, with a limited number of courses and a matching institutional footprint absent of the architecture and foundations to secure recognition across institutions in UK HE. That ultimately configures a fundamental vulnerability in the reproduction of IPE. Simultaneously, career progression, the successful pursuit of research funding, and so on necessitates alignment with that institutional architecture; and perhaps also explains how UK IPE scholars have been able to carve out spaces in journals and particular departments hospitable to them while concurrently looking to cognate fields like political economy and geography for institutional and sectoral support. This might well be another example confirming the bridge building that Clift, Kristensen, and Rosamond argue works to generate exclusions from the IPE mainstream and propels scholars out of IPE.Footnote 62

Where does this leave us in terms of the future of IPE in the UK? We have no wish to be prescriptive, we teased out some necessarily broad brushed reflections on these potential issues alongside our interpretation of the first set of survey data. Beyond further iterations of the survey the article also raises a number of possibilities for developing future research through expanding the methodological techniques employed in this initial intervention that would incorporate more of our own determinations of who counts as IPE in UK universities, though this runs the risk of imposing our own constructions of a ‘discipline’ with the traditional mechanisms others have identified of gatekeeping, geographical camps, niches, and citation practices.Footnote 63 The indisciplined nature of UK IPE is its strength and collective organisation should not be confused with ‘discipline’ in either an intellectual or institutional sense. The article makes no attempt at offering a definitive roadmap to resolving these problems, but we hope that it stimulates debate on the desirability and shape of what that roadmap might look like.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2016 International Initiative for Political Economy Conference at Berlin School of Economics and Law, the 2017 British International Studies Association International Political Economy working group annual workshop at the University of Liverpool, and the 2018 International Studies Association annual convention in San Francisco. Ian Bruff, Randall Germain, Huw Macartney, Chris May, Len Seabrooke, and Dani Tepe provided invaluable commentary on and support for earlier drafts. We'd also particularly like to acknowledge the three referees for the journal. Despite the time and workload pressures, all three referees engaged so thoroughly with the initial version, offering robust but positively framed criticisms that we greatly appreciated. Thank you. The Global Inequalities programme at Leeds Beckett University generously funded the use of a survey company to conduct the research. Usual caveats apply.