The history of antipsychotics began when the sedative effects of chlorpromazine were first reported by Delay & Deniker in 1952, Reference Delay and Deniker1 and entered into clinical practice in many countries the following year. This was a significant milestone in the treatment of acute psychosis, but despite isolated reports over the subsequent decade, Reference Scarpitti and Pasamanick2,Reference Prien, Cole and Belkin3 the exact significance of long-term medication in the prognosis of schizophrenia remained unknown. The development in 1966 of antipsychotic long-acting injections (LAIs) was due to the initiative of G. R. Daniels, who at that time was the medical director of E. R. Squibb & Sons Ltd. The first LAI was fluphenazine enanthate in 1966 and the second, some 18 months later, was fluphenazine decanoate. The first clinical evidence of potential benefit came from the UK on the completion of two ‘mirror image’ studies, when the duration and frequency of admissions to hospital were compared over identical periods before the use of LAIs and after the initial prescription. Reference Denham and Adamson4,Reference Johnson and Freeman5 It was accepted that this method of investigation has a number of problematic design faults, but the results showed a dramatic reduction in morbidity. A Danish pharmaceutical company (Lundbeck) next introduced flupenthixol decanoate, and a mirror-image study in Sweden gave almost identical results. Reference Gottfries and Green6

The concept of antipsychotic LAIs for psychotic illness was not, initially, warmly received by the medical profession (psychiatrists and general practitioners alike). Injectable forms of medication had only previously been used in gynaecology. Also, the case against continuous medication was argued strongly by certain influential psychiatrists and fears of increased side-effects were widespread. Many psychiatrists simply did not accept that an LAI alone would result in an ongoing therapeutic dose, and as a consequence wanted to add oral medication as an ‘insurance strategy’. Even more importantly, the increasingly vocal groups interested in ‘freedom of choice’ and ‘human rights’ during the late 1960s and early 1970s, who had introduced terms such as ‘chemical straitjacket’ or ‘chemical cosh’, saw this new method of administration of treatment as an attempt by psychiatrists to impose a treatment upon patients without due regard to their feelings or rights. However, the increasing awareness among clinicians of the unreliability of patients, non-psychiatric as well as psychiatric, in taking drugs regularly for long periods motivated the gradual increase in the use of an LAI, as well as acceptance of the emerging scientific data.

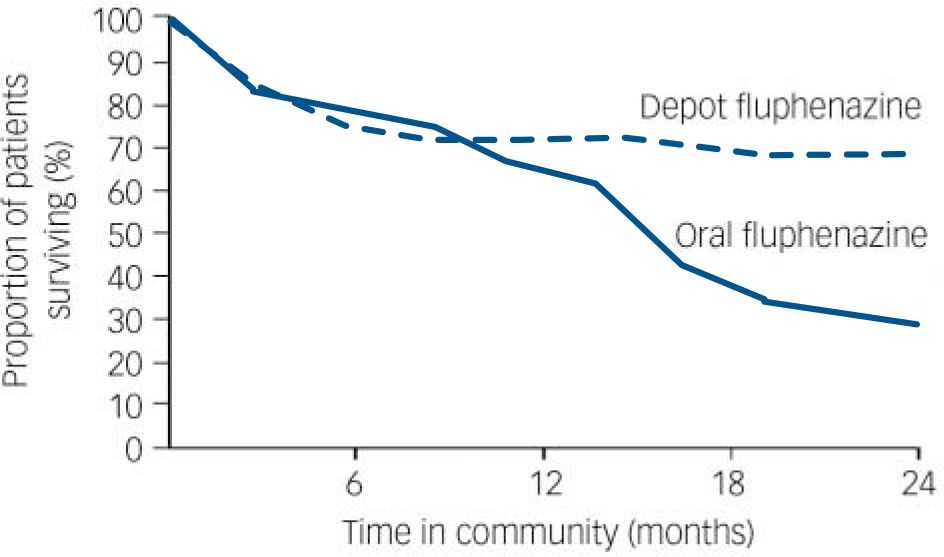

A series of double-blind prospective studies confirmed the importance of LAIs in both chronic or relapsing schizophrenia and first-illness schizophrenia. Reference Hogarty, Goldberg and Schooler7–Reference Pietzcker, Gaebel, Kopcke, Linden and Muller21 In a comparison of oral and LAI fluphenazine, Hogarty et al demonstrated that relapse rates were notably worse for patients taking the oral formulation, but this was not apparent until after at least a year of treatment (Fig. 1). Reference Hogarty, Schooler, Ulrich, Mussare, Ferro and Herron22 The prescribing of LAIs for out-patient maintenance therapy continued to grow worldwide, although the use varied considerably in different countries. Reference Kissling23 Psychiatrists in the UK appeared to be initially using LAIs most widely, with one study showing that 80% of out-patients with psychosis were receiving this treatment. Reference Johnson and Kissling24 Sweden and Austria had approximately 50% of out-patients treated with an LAI. Reference Dencker and Kissling25,Reference Fleischhacker, Meise and Kissling26 Germany and the USA had the lowest use: only 12–20% of patients in the USA were receiving LAIs, and overall the use in Germany was probably in the region of 20–30%. Both America and Germany had particular delivery problems, with reliance on general practitioners and other professionals to give the injections.

Fig. 1 Survival curve for patients treated with fluphenazine in the community (time to relapse): depot v. oral formulation. Reproduced with permission from Hogarty et al. Reference Hogarty, Schooler, Ulrich, Mussare, Ferro and Herron22

Historical background

To have a more complete understanding of the development of the use of long-term medication, particularly in the community, it is important to be aware of the parallel changes taking place in psychiatry at that time, which were partly based on an evolution of clinical practice and knowledge over many years.

Setting the scene

Cooper & Shepherd suggest that modern notions of psychiatry may be said to date from the publication of Pinel's Traite Medico-philosophique in 1801, Reference Cooper, Shepherd and Price27,Reference Pinel and Davis28 which included a range of potential social, emotional and physical causes for mental disorder. They also highlight Pinel's statistical approach to classification. A unitary psychosis with multifactorial causation enunciated by Griesinger in 1867 and the influential Kraepelinian system of classification in 1896 were both considered as further advances for psychiatry. Reference Cooper, Shepherd and Price27 Bleuler in 1911 introduced the term ‘schizophrenia’ for the concept of dementia praecox, with emphasis upon flattening of affect and loosening of associations.

In the 1970s there was a dramatic resurgence of interest in classification, particularly in the USA. Reference Kendal, Pighot and von Cranach29,Reference Kendal, Kerr and Snaith30 This new outlook was heralded by the publication of strict operational criteria for the diagnosis of 15 major syndromes, Reference Feigher, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz31 and then proclaimed 8 years later by the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–III). 32 Before this there were serious international differences in diagnostic concepts, particularly between North America and Europe. Reference Leff and Wing33 The previous broader diagnosis of schizophrenia in the USA was well illustrated by the World Health Organization's International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. 34 It is only since the 1970s that it has been possible to have truly international research or full understanding of research from other countries. This development of an international standardisation of diagnostic methodology subsequently enabled more consistent identification of schizophrenia to which a specific treatment regimen could then also be more consistently applied.

Evolution in the management of schizophrenia

Mandelbrote divides the management of schizophrenia into various time-related era. Reference Mandelbrote and Price35 The moral era (1825–75) described the importance of the social setting in which ‘treatment’ took place and led to changes in the social setting of mental hospitals. Greenblatt et al summarised it ‘as therapy that emphasized close and friendly association with the patient, intimate discussions of his difficulties and the daily pursuit of purposeful activity’. Reference Greenblatt, York and Brown36 The benefit of social change within the hospital environment is illustrated by a follow-up study over 20 years of first admissions in the USA, Reference Bockhoven37 which suggested a high rate of discharge from hospital; 70% were discharged as recovered or improved. Even among patients with chronic disorder, 45% were discharged as recovered or improved. The custodial era refers to a later period between the end of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. The emphasis was on institutional care, supervision and regimentation. It resulted in a significant fall in discharges and a rapid increase in the patient population. The prime consideration was the protection of the community. Nevertheless, a review of surveys in the USA by Standt & Zubin showed that approximately 30–40% of individuals with acute schizophrenia recovered or improved over a 5-year period. Reference Standt and Zubin38

Between the two World Wars a number of treatments were introduced. These included insulin coma, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and intensive occupational therapy. The first two have long since been abandoned, apart from ECT in catatonic states or depressive phases resistant to other treatments. Moniz introduced prefrontal leucotomy as a treatment for schizophrenia, Reference Moniz39 but this was discontinued because of the resultant personality changes and other unwanted effects. Formal psychotherapy was tried in schizophrenia but the outcome over 5 years was no different from the spontaneous remission rate. Reference Appel, Lhamon, Myers and Harvey40

After the 1950s the new formally trained psychiatrists began to evaluate critically the symptoms of schizophrenia and the treatments offered, thus recognising that not all the associated disabilities were an essential part of the illness, but that some resulted from prolonged residence in a restrictive and socially sterile institution. The mental hospitals began to change and adopt features of the ‘therapeutic community’. Wing & Brown in their study of female patients with schizophrenia concluded that there was good preliminary evidence that the social conditions in a mental hospital do influence the patients' mental state. Reference Wing and Brown41 An increasing number of patients were admitted and discharged. It was against this changing social background in the pattern of management of schizophrenia that new pharmacological preparations were introduced into clinical practice in the 1950s (phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and the benzodiazepines), leading to the antipsychotic LAIs in 1966.

Birley & Brown found, first, that both life events and reducing or stopping phenothiazines acted as precipitants of schizophrenia (i.e. non-adherence leading to possible relapse), and second, that the symptoms of acute schizophrenia were largely unrelated to its precipitants. Reference Birley and Brown42 The increasing reliance on medication was in part because social change was more expensive to achieve, took place more slowly and was dependent on a change of attitudes not only within the psychiatric profession but also among the general public. However, the research evaluating the social influences upon schizophrenia has not been without its critics, and a balanced view is presented by Bebbington & Kuipers. Reference Bebbington, Kuipers, Bebbington and McGuffin43 No single treatment should be regarded as exclusive. Reference Greenblatt44,Reference Bebbington and McGuffin45

Long-acting injections and community care

The development of the concept of ‘community care’ meant more individuals with schizophrenia were discharged into the community, often with an incomplete resolution of symptoms. This led to an increased burden being placed upon the family, causing stress to the relatives and in turn an adverse effect upon the patient's mental state. The role of the family in assisting medication adherence in the community was noted. Also, the importance of supporting the family and offering some form of intervention to help relieve the family stress soon became clear. Taylor et al reported that good social performance of the patient is found when the patient's closest associate has a large diffuse network with low density, a large number of non-kin people who visit him, and people on whom he can rely. Reference Taylor, Huxley and Johnson46 At the time antipsychotic LAIs were launched, the health service was a tripartite system in which the hospital, general practitioners and the public health service (embracing social workers) functioned independently. Psychologists were not yet an independent profession and they were almost completely hospital-bound. It became generally accepted that a ‘community mental health service’ was required that linked not only to extramural facilities, but also to a comprehensive programme of care and treatment, including all hospital services. Reference Freeman47 It soon became clear that unless professionals (particularly nurses and social workers) had some formal training in psychiatry and regularly liaised with the rest of the psychiatric team, the care arrangements seldom survived. The initial defaulting rates from LAIs were considerable. An outline of how this was attempted in one city in the UK, and the progress achieved is described by Freeman & Johnson. Reference Freeman and Johnson48 It was into this fragmented health service, with only the very beginning of cooperation between the various elements of service, that LAIs were launched. From the very beginning the advantages of a community psychiatric nursing service, not just to deliver injections but to act in a wider support role, were advocated.

The changes to the structure of health services during the latter part of the 20th century created the circumstances (i.e. more out-patient and community care) that made the delivery of LAIs possible and necessary. This was coupled with the progressive deinstitutionalisation of mental healthcare, and the recognition that everyone (including psychiatric patients) is liable to non-adherence or partial adherence to long-term prescribed medication. It can be seen therefore that any improvements in care and outcome in cases of schizophrenia were attributable to the combination of evolving social and pharmacological care.

Continuous maintenance medication

It became increasingly clear that not only did phenothiazines control the symptoms and distressed behaviour of the acute psychotic illness, but continuous medication for a prolonged period thereafter prevented, delayed or modified a further relapse. Reference Prien, Cole and Belkin3,Reference Davis11,Reference Schooler, Levine, Severe, Brauzer, DiMascio and Klerman14,Reference Wistedt16,Reference Kane, Rifkin, Quitkin, Nayak and Ramos-Lorenzi17,Reference Crow, McMillan, Johnson and Johnstone20,Reference Kissling23,Reference Leff and Wing33,Reference Davis, Schaffer, Kinard and Chan49–Reference Barnes, Hirsch and Kissling51 It was also demonstrated that continuous, or maintenance, medication could protect individuals with schizophrenia against the stress of their environment which often arose from within their own families, Reference Brown, Birley and Wing52,Reference Vaughn and Leff53 and facilitate the delivery of social interventions and rehabilitation which formed part of their treatment package. Reference Hogarty, Ulrich, Goldberg, Spitzer and Klein9,Reference Hogarty, Goldberg, Schooler and Greenblatt54 However, approximately 20–25% of all patients with schizophrenia have a good prognosis, independent of active maintenance medication. Reference Leff and Wing33,Reference Cutting, Kerr and Snaith55 Unfortunately no satisfactory method of identifying this good prognosis group has emerged.

Problems in the early days of long-acting injection use

Need for medication adherence

By the 1960s there was a widely held view that communication between medical professionals and their patients needed improvement. Ley & Spelman investigated this problem in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients. Reference Ley and Spelman56 They found that a quarter to a half of patients failed to recall instructions, even when their importance was emphasised. In their review of the literature, they found that the same percentage of individuals failed to follow instructions concerning medication even when a serious illness such as tuberculosis was involved, or they were mothers who were responsible for their baby's care. Reference Ley and Spelman56 Wilcox et al showed that 48% of psychiatric out-patients failed to take their medication, Reference Wilcox, Gillan and Hare57 and Neve found that 11% of in-patients on chlorpromazine failed to take medication as prescribed. Reference Neve58 Prospective studies in the setting of general practice showed similar results. Reference Johnson18,Reference Johnson59,Reference Johnson60 With the increasing weight of evidence that maintenance medication was essential, the need for improved medication adherence was self-evident. The LAI offered great potential in this respect. In particular, it identified the actual drug and dose taken, to allow informed decisions to be made about future treatment. Unfortunately, prospective monitoring showed that drug defaulting on an LAI without a specific system of organisation was also considerable. The infrastructure to develop specialised clinics within the community and arrange for psychiatric-trained nurses to follow up defaulters simply did not exist at that time. Attempts to involve non-psychiatric-trained district nurses (who were not part of the hospital or the psychiatric service) or general practitioners largely proved a failure. Reference Johnson and Freeman61 The need for special delivery services such as LAI or depot clinics or outreach facilities, whether hospital- or community-based, was apparent. Happily, over time the development of the mental health service has been transformed. The service is now more integrated, with psychiatrists, general practitioners, community psychiatric nurses, social workers and psychologists all working in the community, often in well-defined roles as assertive outreach teams, early intervention teams, home treatment teams or dual diagnosis teams. The adoption of these community team strategies has probably reduced drug defaulting from oral medication.

Injection frequency

A number of mistakes associated with the initial use of the LAI compounded the very real problems of side-effects, principally extrapyramidal symptoms, and the need for an efficient drug delivery system. These mistakes continue to haunt the correct use of LAIs and the often related problem of polypharmacy. The original LAI of fluphenazine enanthate was recommended to be given every 2 weeks. Two years later, fluphenazine decanoate was introduced as a 3-weekly injection. The next available preparation, flupenthixol decanoate, was also recommended as a 3-weekly injection. The concept of an individual flexible dose regimen was initially completely overlooked, possibly because it did not fit the marketing strategy of the time. This was a major error because flexibility is the key to maximising the therapeutic benefits and minimising the adverse effects of drug therapy. This was increasingly recognised from the mid-1970s onwards. Reference Baldessarini, Cohen and Teicher62–Reference Marder, van Putten, Mintz, Lebell, McKenzie and May65 In addition, regular consideration needs to be given to the dose prescribed, with an aim of achieving the minimum effective dose for long-term care. Reference Kissling, Kane, Barnes, Dencker, Fleischhacker, Goldstein and Kissling66

Extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia

Extrapyramidal symptoms when they occurred as a side-effect were usually treated with an anticholinergic drug, and some clinicians even prescribed such drugs on a routine basis as a prophylactic measure. The strategy of increasing the interval between injections and/or adjusting the injection dose was seldom explored. One study demonstrated that by varying the dose regimen, such as by giving smaller doses more frequently, the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms could be reduced to 34%. Reference Johnson67 By delaying the next injection for 2–3 weeks, and sometimes even longer, before introducing the new dose regimen the symptoms often settle without recourse to additional treatments. The very real risks associated with the prescription of anticholinergic drugs, Reference Johnson68,69 which include physical and psychological side-effects and an exacerbation of existing tardive dyskinesia, may possibly be avoided. Another consideration is to note that the prescription of a tricyclic antidepressant in combination with an antipsychotic may have an adverse effect on existing tardive dyskinesia. Reference Johnson68 The wide-ranging disadvantages of polypharmacy to the patient, particularly with the overuse of anticholinergic drugs, were never fully appreciated or addressed by psychiatrists and continued over many years despite repeated warnings. This is not to deny the very real benefit to individual patients of additional drugs, particularly the selective prescription of anticholinergic drugs to patients with Parkinsonism unresponsive to other strategies and ‘akinetic’ depression. Reference Johnson67

Antidepressant co-prescribing

Antidepressants were often added without due consideration of the cause of any apparent depressive signs or symptoms. The causes of depression in the course of treated schizophrenia are many and varied. Reference Johnson68,Reference Johnson70–Reference Brockington, Kendell and Leff82 They include premorbid personality, post-psychotic depression, drug-related akinetic depression, depression as a symptom of schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychoses. In the early days of antipsychotic treatment, surveys of drug prescriptions to patients with schizophrenia revealed that at least 20% were prescribed antidepressants, yet no study showed that the broad spectrum of patients gained any benefit. Only Siris et al, studying a group of patients with post-psychotic depression, reported any overall advantage. Reference Siris, Williams and Dalby83 Again we had the problem of polypharmacy – with the risk of a spectrum of unwanted side-effects, including worsening of tardive dyskinesia – for no justifiable reason.

The problems of polypharmacy were not fully appreciated by all psychiatrists, and repeat surveys showed that it remained a problem for many years. Reference Johnson and Wright84

Administration of LAIs

Other important early difficulties included the problem that drug administration often was not centralised nor carried out by team members with appropriate training in mental health. The occasion for an injection administration was not seen as an opportunity to support and evaluate the patient, both for changes in mental state and the early development of side-effects. Health staff who were not sympathetic to psychiatric problems may have played a part in significant defaulting among patients receiving LAIs and less than optimum care in many respects. Reference Johnson and Freeman61 The use of LAI or depot clinics then fell somewhat from favour with some psychiatrists, and has been considered as leading to stigmatisation of patients. Reference Johnson72,Reference McGlashen and Carpenter73 As a consequence, it was suggested that such clinics should be renamed ‘maintenance medication clinics’, although it also is essential to recognise that research and experience has demonstrated that the success of LAIs rests with the quality of the follow-up service, Reference Johnson and Freeman61 which now includes several forms of service delivery within the community.

Duration of maintenance treatment

Over time the treatment of people with schizophrenia has been increasingly based in the community, involving a widening range of professionals offering supervision and advice to patients and their families. A survey in 1997 by teleconference was carried out to explore the professional attitudes of psychiatrists, general practitioners, pharmacists and community psychiatric nurses, throughout all parts of the UK, towards the duration of maintenance therapy for both first-episode and multi-episode illnesses. Reference Johnson and Rasmussen85 The results caused grave concern in that the professions varied widely in the advice they offered to patients and their families, and this was often substantially different to the multinational Consensus Group recommendations which were widely accepted worldwide. Reference Kissling23 For first episodes, over half of psychiatrists recommended 1–2 years of maintenance therapy, but only 45% of general practitioners, 33% of community psychiatric nurses and 30% of pharmacists recommended similar periods. For multi-episode disorder, the variation was even greater: 90% of psychiatrists recommended 3–5 years or more of maintenance therapy, but only 79% of community psychiatric nurses, 69% of general practitioners and 55% of pharmacists recommended similar periods.

It is recognised by the author that no individual or authority can give absolute guidelines with regard to duration of maintenance therapy with antipsychotic drugs, but the issue is the conflict in information received by patients and their families, and the likelihood that this will influence adherence.

Advent of oral second-generation antipsychotics

The introduction of oral second-generation antipsychotics (SGA–orals) brought claims of improved tolerance. Many of these drugs were an attempt to reproduce the efficacy of clozapine, which was reintroduced to the UK in 1989, but without that drug's adverse side-effects, including agranulocytosis, which required regular monitoring. Despite a wave of optimism regarding potentially superior outcomes, the increased use of SGA–orals did not lead to clear evidence of significant improvement in adherence. The claims for a reduced risk of extrapyramidal side-effects and tardive dyskinesia have yet to be confirmed. Reference Kissling86–Reference Jones, Barnes and Davies90 The existing trial results can be criticised for design faults, contamination by previous medication and short duration of follow-up. It must also be recognised that the SGA–orals may have a side-effect profile that differs from that of first-generation antipsychotics. It has been suggested that there are increased risks of hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, raised blood pressure and increased weight gain. Reference Cassey87–Reference Shirzadi and Ghaemi91 The jury is out on the true risk–benefit ratio of the SGA–orals.

In more recent years, with ongoing community psychiatry, concern by the public has been expressed regarding individuals with schizophrenia who are perceived as dangerous. This is based not only on a number of tragedies (including the Clunis case), Reference Blom-Cooper, Hally and Murphy92 but also on untoward stereotyping in the media. This includes the overstating of concern about medication non-adherence. Nevertheless, due consideration must be given to the appropriate drug delivery system and whether LAIs might be more easily monitored. This is an important issue, as these tragedies have influenced the public perception of mental illness. The UK government response has been in part to increase significantly the resources devoted to forensic mental health services. It was shortly thereafter that the first SGA–LAI, risperidone, was introduced. Most recently, community treatment order legislation was introduced in the UK.

Conclusion

Over the past 50 years there has been a major change in the training of psychiatrists and the practice of psychiatry. In the UK, psychiatrists now all receive formal training under the supervision of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The asylums have closed; bed numbers have been much reduced, and are either in general hospitals or small specialised units. The treatment of patients is either entirely in the community, or with periods of short-term in-patient care. In 1999, the introduction of the National Service Framework for Mental Health Services provided a major blueprint for adult mental health services in England. Reference Thornicroft93 Its introduction was responsible for subsequent funding, which has transformed mental health services by raising standards of service provision and delivery, including defining performance indicators. Our knowledge of the social influences upon mental health and the course of mental illness has increased immensely. Consequently, community services have expanded and developed; nurses have developed new qualifications and roles, both within the hospital and especially within the community; and psychologists have become an independent profession, bringing new psychological treatments to the care of patients. The emphasis is very much on mental health teams offering care and support within the community, involving all disciplines.

In the 1950s a range of new drugs were introduced including the antipsychotics. Unfortunately, poor adherence was found to be a major factor. The development of LAIs (initially called depot injections, which would be the author's preferred terminology since it accurately describes the delivery of esterified drugs) was an attempt to overcome this problem. It was soon found that this form of drug delivery was only successful in the setting of an organised psychiatric team to supervise and monitor the drug treatment. Although the use of LAIs was widely adopted, Reference Johnson and Kissling24–Reference Fleischhacker, Meise and Kissling26 with repeat surveys suggesting this might be a superior form of drug delivery, Reference Rifkin, Quitkin and Rabiner12–Reference Schooler, Levine, Severe, Brauzer, DiMascio and Klerman14,Reference Hogarty, Schooler, Ulrich, Mussare, Ferro and Herron22 a number of prescribing problems were identified. Over time it was recognised that individual flexibility of dose, coupled with minimal polypharmacy, was essential to reduce side-effects, particularly the severity of tardive dyskinesia. It was also realised that the structure required for the successful use of LAIs could offer much more in the way of patient care than merely the administration of an injection alone. No additional side-effects from the use of injections should be anticipated, apart from painful injection sites described by some patients, since the drug administered is essentially the same whether taken by mouth or injection. Nevertheless, the use of LAIs requires its own skills. The introduction of the oral SGAs brought claims of better tolerance and fewer side-effects, despite a lack of clear scientific evidence. I believe the jury is still out. The use of first-generation antipsychotic LAIs has declined. Reference Patel, Nikolaou and David94,Reference Patel and David95 The introduction of second-generation antipsychotic LAIs allows psychiatrists once again to prescribe LAIs without losing any of the potential advantages of the SGAs, if shown to exist, by using this form of delivery. It is important that the lessons learnt over many years of clinical practice (e.g. working with flexible dosing frequency for LAIs), should not be lost.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.