1. Introduction

Over the last decade, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of evidence-based policy in reaching decisions about criminal justice programmes and practices.Footnote 1 Indeed, it is reasonable to say that the idea of evidence-based decision making has become key not only to theory but also to practice. Evidence-based policy requires that decision making in criminal justice be strongly influenced by basic and applied research. For example, large-scale programmes would not be widely implemented without strong scientific evidence of programme success. In turn, programmes that are implemented would be evaluated and assessed on a regular basis to ensure that they are meeting the goals of the organisation.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), which is the main funder of criminal justice programmes in the United States (US), declares on its website that ‘[e]ncouraging the adoption of E[vidence] B[ased] P[ractices] is a key component of BJA's 2013–2016 strategic plan, which calls for the promotion and sharing of evidence-based and promising practices and programs’.Footnote 2 Even earlier than this, in 2004, the Community Corrections Division of the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) had already started working together with the Crime and Justice Institute to develop an ‘integrated model’ that ‘emphasizes the importance of focusing equally on evidence-based practices, organisational development, and collaboration to achieve successful and lasting reform’.Footnote 3

In some sense, it would seem intuitive that evidence-based policy is a useful tool for government. A recent report by the Pew Charitable Trusts describes the policy in the following terms:Footnote 4

Evidence-based policymaking uses the best available research and information on program results to guide decisions at all stages of the policy process and in each branch of government. It identifies what works, highlights gaps where evidence of program effectiveness is lacking, enables policymakers to use evidence in budget and policy decisions, and relies on systems to monitor implementation and measure key outcomes, using the information to continually improve program performance.

Why would government not want to use the best available research and information to inform policies and practices? Shouldn't evidence-based policy approaches be easy to integrate and implement for criminal justice government agencies?

In many papers that advocate evidence-based policy there is much discussion of the benefits to government if it adopts the evidence-based approach.Footnote 5 This can give the impression that the ‘road to evidence-based policy’ is a direct one in which agencies will naturally adopt the policy because of its convincing logic. Once adopted, evidence-based policy will naturally infuse and permeate itself throughout an agency because it provides a more scientific decision-making model. However, many commentators have identified barriers to implementation of the policy, and it is clear that the road to evidence-based policy often includes difficulties that agencies find hard to overcome.Footnote 6

In this article we use our experience in implementing evidence-based policy in the Israel Prison Service to illustrate the extent to which the adoption of the policy is affected not only by the inherent utility of the approach but also by the vagaries of human interactions and circumstances. We also emphasise in this context the importance of practitioners taking ownership of evidence-based policy. These themes were raised by one of the authors of this article in earlier work that emphasised how key individuals impact upon the implementation of the policy.Footnote 7 Our story overall is a positive one. At the same time, it suggests that the road to implementation of evidence-based policy is not direct and that it is dependent on human factors which influence the introduction of the policy and its implementation as a long-term strategy. In turn, our experience should be informative to researchers about the need to abandon the idea of a fairy-tale happy ending to the road to evidence-based policy. It is not only a winding road; the full implementation of the policy will often be quite difficult to achieve. Of course, following the above quote from Ethics of the Fathers, the fact that one cannot fully achieve the goals of evidence-based policy in practice does not mean we should abandon efforts to do so.

2. The Importance of Human Agency in Implementing Evidence-Based Policy

While the adoption of evidence-based policy is often traced to the value of the approach itself and the benefits it can bring to organisations in developing policies, programmes and practices, the realities of adoption are often dependent on the specific experiences of key people who have the authority to make and lead change in organisations. Indeed, in some sense the ultimate adoption of evidence-based policy can be seen more as an example of the importance of human agency than the inevitability of improvement in government decision making. By human agency we mean ‘the human capability to exert influence over one's functioning and the course of events by one's actions’.Footnote 8 This point is made by Telep and Weisburd in an article on the development of evidence-based science in systematic reviews.Footnote 9 They note that the major increase in the number of policing-related systematic reviews in recent years was made possible in large part because of the leadership of an innovative practitioner, Peter Neyroud, who previously headed the National Police Improvement Agency in the United Kingdom (UK). Neyroud had pioneered evidence-based approaches in UK policing in good part because of his contacts with criminologists associated with the Campbell Collaboration.

A similar description is offered by Farrington in detailing the history of experimental research in criminology.Footnote 10 While strong science can be developed using quasi-experimental methods as well, experiments allow strong assumptions of causality and have been seen as key to evidence-based policy in practice.Footnote 11 Farrington argues that ‘feast and famine periods [in experimental criminology] were influenced by key individuals’.Footnote 12 These key individuals, in combination with fluctuations in funding and priorities, often have major influence over the type and quality of research being conducted. For example, Palmer and Petrosino charted the history of research in the California Youth Authority, finding that support from higher levels in the agency and the research division, most prominently Herman Stark and Keith Griffiths, facilitated a series of important randomised experiments in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 13 Stark directed the California Youth Authority from 1952 to 1968 and Griffiths served as the director of the Division of Research from 1958 to 1983. These leaders fostered a culture in which quality research was supported and highly regarded, being considered an essential component in decision making regarding correctional programming. As these and other individuals eventually retired or were replaced, subsequent directors tended to feel more politically vulnerable and the agency became increasingly risk averse, thus being less likely to use rigorous methodologies to evaluate programmes.Footnote 14

Similarly, Nuttall documents changing priorities in the UK Home Office, which became much more averse to funding randomised experiments with Ronald Clarke's tenure in the Home Office Research Unit.Footnote 15 In this case, Clarke and Derek Cornish had been highly critical of the usefulness of randomised trials in advancing knowledge.Footnote 16 As Farrington and Welsh note: ‘The Clarke-Cornish critique was very influential in ending Home Office-funded randomized experiments for a quarter century’.Footnote 17 This illustrates the fact that key individuals cannot only advance evidence-based policy in agencies; they can also hinder or reverse advances that had been made by earlier leaders.

3. Human Agency and the Advancement of Evidence-Based Policy in the Israel Prison System

The introduction of evidence-based policy in the Israel Prison Service (IPS) was led by Benny Kaniak, the Commissioner of the Prison Service from 2007 to 2011. Commissioner Kaniak had previously been the Deputy Commissioner of the Israel Police. During that period he was responsible for communications between a large-scale evidence-based study of policing terrorism and the Israel Police. The study was expected to be funded jointly by the Ministry of Public Security in Israel, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) in the United States. As the senior representative of the police, Commissioner Kaniak worked with one of the authors of this article (Weisburd) in developing the parameters of the jointly funded study.

In some respects, the study highlights the challenges of evidence-based policy to take root in the Israeli criminal justice system. The funding agencies had agreed to provide USD 450,000 for the project (split equally between the three agencies) and negotiations about potential security challenges and other questions had begun successfully. However, serious barriers were encountered in the development of a contract. The Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Public Security wanted a clause in the contract stating that no publications or information could be released without his approval. He believed that the Ministry, as funder of the work, should have the right to review and censor publications. This review would be independent of the ‘security review’ which had been agreed by all parties to prevent the release of sensitive government information affecting national security.

A key component of evidence-based policy is recognition by agencies of the importance of the values of science.Footnote 18 One such value is academic freedom in the production of scientific knowledge. Of course, some knowledge in areas where security concerns are examined must be kept from the wider public, but, as far as possible, science must be transparent and open. The NIJ and DHS were concerned that the additional censorship required by the Ministry of Public Security would affect the quality of the study because of its potential to ‘reign in’ researchers from criticising policing practices. However, the Chief Scientist of the Ministry refused to back down on his demand, which led to the project being redesigned and developed without the participation of the Ministry.Footnote 19

What seemed like a failure for evidence-based policy in Israeli criminal justice was to lead indirectly to the establishment of the most important evidence-based policy programme in Israel to date. In 2007 Deputy Chief Kaniak was made Commissioner of the IPS. Despite the resistance to principles of evidence-based policy at the Ministry, Commissioner Kaniak came to view the policy as an important tool for advancing practice. A year later he invited one of the authors of this article (Weisburd) to his office to discuss how evidence-based science could be better integrated into the work of the prison service. Weisburd suggested that an important step was to create an Academic Advisory Board made up of scholars from universities and colleges in Israel. Commissioner Kaniak accepted this recommendation and on 15 November 2009 the Academic Advisory Board's first meeting convened.Footnote 20 The idea of creating a specific Research Unit in the IPS was discussed during these initial meetings and contacts. The Commissioner subsequently established a Research Unit and recruited a PhD researcher, Dror Walk, to head the Unit as a senior commander in the IPS. The appointment of a Director of the Research Unit at a high rank in the agency was indicative of the importance being attached to the new Unit.

The Academic Advisory Board put forward a number of recommendations. Perhaps the key recommendation was to develop a research programme for evaluating rehabilitation initiatives in the prison service. While the IPS was given a formal role of incarceration of criminals and their removal from society, almost from the outset there has been an emphasis on treatment and educational activities. In the late 1990s, this policy was consolidated by the IPS administration and anchored in the following mission statement:Footnote 21

The Israel Prison Service is a security organisation with a social mission and part of the law enforcement system. The essence of its role is: holding prisoners and detainees in safe and suitable custody, while respecting their dignity, supplying their basic needs, and providing all appropriate prisoners with corrective tools, in order to improve their ability to integrate into society upon their release.

There are several programmes geared to rehabilitation in the IPS. The total prison population for criminal offenders in Israel is estimated at 12,000 inmates.Footnote 22 In 2010, about 2,200 participated in employment or vocational programmes of some variety. About 3,000 additional prisoners performed daily work inside the prisons in maintenance, kitchen or other services, and 2,300 prisoners worked in 54 factories operated by the IPS. Furthermore, the IPS runs about 40 different vocational programmes in which 700 prisoners participate every year.Footnote 23 In 2009, 276 formal education classes operated in the IPS in which 4,300 inmates participated (more than a third of the total prison population). With regard to treatment programmes, the prison service runs 235 treatment groups for drug, alcohol and other addictions, domestic violence and sexual offending, in which 3,800 prisoners participate every week.Footnote 24

Despite the wide-scale support for rehabilitative programmes in the IPS, there had been only a handful of evaluations of their effectiveness.Footnote 25 The Academic Advisory Board advocated a large-scale research programme that would systematically evaluate IPS rehabilitation efforts. The Commissioner voiced his support for such a programme, though there had never been such wide-scale interest in scientific evaluation in the prison service, or for that matter in any of the Israeli criminal justice agencies. In December 2010 the IPS issued a call for proposals, which attracted five applications from various research teams. The funding was awarded to a team of researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, led by the authors, and a team at Ashkelon College, led by Professor Efrat Shoham. The proposed study would use a quasi-experimental research design with a commonly used methodological approach for drawing conclusions about programme effectiveness – propensity score matching (PSM).Footnote 26 Finally, cost–benefit analysis would also be conducted. This model for an evaluation research programme was based on the tenets of evidence-based policy.

The study began in 2012 and was established as a long-term (five-year) evaluation programme. The study's researchers are examining the effectiveness of more than twenty rehabilitation programmes operated by the IPS, including the group work release programme, educational programmes, a programme for the reduction of domestic violence, programmes for the cessation of drug and alcohol addiction, vocational training programmes, employment programmes, a programme for the rehabilitation of sex offenders, and programmes that include religious study.

Thus far, the experience of the prison service in evidence-based policy suggests the importance of what are seemingly unconnected, or at least unplanned events. Commissioner Kaniak's experience with the failed Ministry of Public Security policing terrorism study led him to have contact with researchers committed to the policy. This contact was key to his adoption as Commissioner of the basic model of evidence-based policy in the field of corrections. In chaos theory, a small set of causes early on can lead to the development of a major event.Footnote 27 Here, the establishment of the largest effort in evidence-based policy in criminal justice in Israel to date can be traced back to discussions which seemed to have led to failure rather than success in advancing the policy.

More generally, however, our story shows the importance of human agency in the development of evidence-based policy. Commissioner Kaniak was the key figure in the establishment of evidence-based corrections in Israel. Without him and his decision to work with senior academic figures, evidence-based policy would not have emerged on its own during that period.

4. Establishing the Legitimacy of Evidence-Based Science

While Commissioner Kaniak established a large grant programme of NIS 1,000,000 for the evaluation of prison rehabilitation programmes, his term was completed shortly after the funding of the programme. A key question at that juncture was whether the new Commissioner, Aaron Franco – who had previously been a high-ranking police commander – would support the advances in evidence-based policy that Commissioner Kaniak had pioneered. Again, we can see the importance of human agency in the development of the policy. The two had been colleagues in the Israel Police and Kaniak had impressed on Franco the importance of both the new project and new approach for the prison service. Commissioner Franco was to become a strong advocate for evidence-based policy more generally. His advocacy was key to the successful advancement of the project. In a hierarchical organisation like the IPS, the support of a senior commander is critical.Footnote 28

At this stage, the prison service had also begun to receive recognition from other government agencies for its efforts in assessing the effectiveness of programmes and its intention to draw information from evaluations in developing future programmes and practices. Such recognition was noted, for example, at a forum of the Israel Democracy Institute which was led by Knesset Member Benny Begin.Footnote 29 In the forum, the efforts of the IPS were noted in positive terms by Begin and representatives of the treasury. In coming years such references to the evidence-based approach of the IPS would become common.

An important component of the project was the integration of the Hebrew University/Ashkelon College researchers with the new IPS Research Unit (which now included two additional researchers, both studying for PhDs in Israeli universities). This approach took into consideration the importance of practitioners taking ‘ownership’ of science.Footnote 30 Weisburd and Neyroud argue that for evidence-based policy to be successfully implemented, three factors supporting ownership of science must be advanced.Footnote 31 First, the organisation must ‘value’ science and become committed to its values. Second, the organisation and its members must become knowledgeable of science and its procedures. Neyroud and Weisburd argue that it is not enough to include outside researchers: the organisation must develop internal knowledge and capabilities which allow it to assess the quality and processes of research used to inform decision making. Third, the organisation and practitioners should become more involved in the world of science, for example, by producing publications and becoming active in scientific meetings and conferences.Footnote 32 For its part, the Research Unit became a key advocate for research and evidence-based policy more generally. It also became a key interpreter for the agency in assessing the activities of the research team and in conveying the importance and relevance of methods of evaluation and findings to the IPS. Perhaps as important, the Research Unit became a partner in the research effort, participating in research meetings and providing key insights into how the research should be conducted.

The Research Unit also played a role in arranging access (for the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team) to the rehabilitation programme staff within the prison. This was particularly important for the qualitative work directed by Efrat Shoham, which informed the models of ‘selection’ for evaluating the programmes. Propensity score models require a clear understanding of the factors that lead to selection into the programme, since these factors become the basis for matching non-treated prisoners with those who received treatment.Footnote 33 By having strong access to programme staff, we were able to develop an intimate knowledge of the programmes that went beyond the statistical data, and to more easily recognise challenges in implementing PSM models. Equally important was the work that the Research Unit carried out in developing quantitative data and measures for use by the research team.

Despite the support of the Commissioners and the Research Unit staff, the team still encountered a good deal of resistance to the project in its initial stages. For example, practitioners expressed their fear that the research would not take into account the realities of the world in which they operated. Another concern was that external researchers would ‘draw (unfair) conclusions’ about the rehabilitation programmes. As we have already noted, the IPS has a strong commitment to rehabilitation. This commitment is one that was not strongly influenced by the ‘nothing works’ movement in American corrections in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 34 The practitioners felt that the project could only ‘bring bad news’ to a system of rehabilitation that they were committed to and believed helped in rehabilitating prisoners.Footnote 35 Practitioners were concerned that researchers who did not ‘care’ about rehabilitation would miss the complicated picture of rehabilitation and draw rash conclusions about the effectiveness of programmes. They were also suspicious of the utility of statistical data and its potential to contradict their clinical knowledge. These types of expression and reaction are not suprising, with similar experiences having been noted in other countries and contexts.Footnote 36

The Research Unit played a key role in mitigating these concerns, although the concerns persisted as obstacles in establishing the legitimacy of the research programme. This resistance was to be clearly showcased at the first Steering Committee meeting. The Steering Committee comprised 17 individuals, including senior IPS staff and representatives from the Ministry of Public Security and the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority. The Chair of the Committee was the Head of Department of Treatment with the IPS, and a Major General with many years of experience. Our research team presented the research design for the programme evaluation and then the first evaluation results. As the first pilot programme for evaluation the Research Unit and the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team chose the work release programme. The choice was strategic because the programme was clearly defined and was believed to be one of the more successful in the prison service. Israel's work release programme includes not only working outside the prison before release, but the integration of therapeutic elements. It is one of the more intensive rehabilitation programmes in the prison. The Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team (led by the authors) agreed that choosing a programme with strong potential for success was a good strategy. The literature supports the idea that being able to present ‘good news’ at the outset can help in allaying concerns of practitioners and improving their receptability to research.Footnote 37

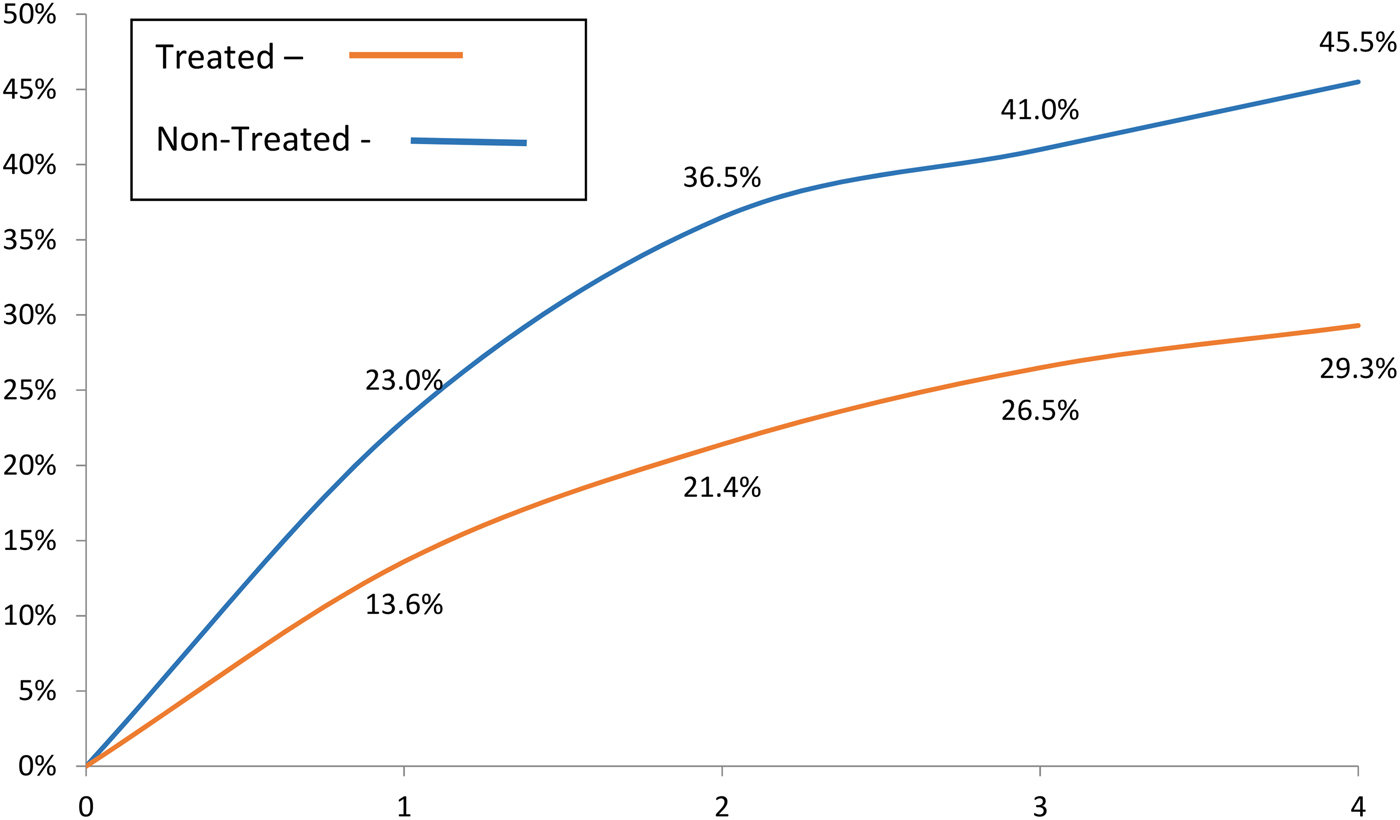

The results of the evaluation were indeed positive. Importantly, the matching procedures yielded strong evidence of the successful development of a valid comparison group.Footnote 38 Figure 1 shows the raw percentage of prisoners re-arrested over four years, comparing the treatment and matched comparison prisoners.Footnote 39 Each year there is a large and statistically significant difference between the treated and untreated prisoners. The Hebrew University/Ashkelon team thought the differences provided strong support for the success of the rehabilitaiton programme, and a good start to the efforts to evaluate prison programmes. Importantly, this was the first time that empirical data on the programme was examined.

Figure 1 Cumulative Proportion of Prisoners Re-arrested for Treatment and PSM Comparison Groups (over Four Years)

When the research team presented these results to the steering committee on 1 September 2013 they expected that it would help to allay the concerns of practitioners. However, the resistance to this work was clear from the start. Practitioners began to raise criticisms of the research and its ability to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes. The Chair of the Steering Committee supported these criticisms and the overall tone was one in which the Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team and the Research Unit were identified as being able to provide only marginal information to the treatment programmes of the prison service. The meeting ended with both the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team and the Research Unit sensing that the Steering Committee was questioning the value of the project more generally.

Following this meeting, the Research Unit arranged for Commissioner Franco and the head of the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team (Weisburd) to discuss the Steering Committee and its role in the project. Weisburd emphasised that the research could not have an impact on the system without the support of the Steering Committee for the overall idea of evidence-based policy in advancing corrections. Criticism was useful and key to providing valid findings, but there was a difference between criticism intended to improve the project and criticism of the overall programme of evidence-based evaluation. Commissioner Franco immediately saw the importance of intervening in the process, and placed himself as the leader of the Steering Committee at the next meeting.

This decision by the Commissioner provided an extremely powerful and important message for a hierarchical organisation like the prison service. Significantly, this again reinforces the idea of the importance of human agency in evidence-based policy. One of the authors (Weisburd) argues elsewhere that policing provides a distinct advantage for carrying out experimental research, because the hierarchy allows the agency head to choose a direction for the agency that others must follow.Footnote 40 A similar situation seems to apply more generally to evidence-based policy in criminal justice in that the heads of organisations like the police or IPS exercise ultimate decision-making authority in the organisation. Of course, other high-ranking officials, as well as the rank-and-file, may try to undermine such decisions. However, in the case of the IPS, where Commissioner Franco had strong legitimacy and where the organisation is relatively small, this did not occur. It was not common for the Commissioner to lead such meetings, and his opening comments at the next Steering Committee meeting reiterated his commitment to the research and evidence-based policy in general, all in the presence of the IPS senior command.

Despite the problems encountered in the Steering Committee, it was clear that the leadership of the IPS had much to offer in developing the research programme. At the original meeting regarding the work release programme, senior staff had brought up the question of whether prior therapy (not included in the PSM model) played a key role in the programme's success. The Research Unit and the Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team sought to answer this important question, collecting data from a different source for a sample of the inmates. The results of the analysis showed that the treatment and control groups were equivalent on this factor.Footnote 41 The fact that this issue had been investigated, and that the general findings were not challenged, appeared to contribute to increased confidence on behalf of the practitioners. Perhaps this was the case because this represented an opportunity to demonstrate that the researchers were being responsive to questions that they raised.

5. The Institutionalisation of Evidence-Based Policy

In the fourth year of the study, two key members of the Research Unit were assigned to new positions. In Israeli criminal justice agencies it is common for staff to move from unit to unit and, indeed, it is critical for their advancement in the agency. While staffing changes in the IPS and the Israel Police facilitate broad organisational experience, essential for developing leadership, these staffing changes work directly in contradiction to the principle of building up research expertise over time. We will comment on this problem again later, but note here that these changes led to a reduction in the ability of the Research Unit to contribute to the research efforts of the evaluation programme.

During this year, Commissioner Franco's term ended and a new Commissioner, Ofra Klinger, was appointed. Commissioner Klinger had chaired the Steering Committee for the project in the final years of Commissioner Franco's term. She communicated continuing IPS support for the project by remaining as Chair of the Steering Committee. At the first meeting an important test for the institutionalisation of evidence-based policy in the IPS took place. At prior meetings the researchers had been able to report findings that were positive overall (or with mixed findings) regarding prison rehabilitation programmes. For example, positive results were found not only for the work release programme, but also for domestic violence and education programmes.Footnote 42 However, at this meeting the Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team presented findings to the Steering Committee that showed negative results regarding a group of programmes that were central to the rehabilitation mission of the IPS.

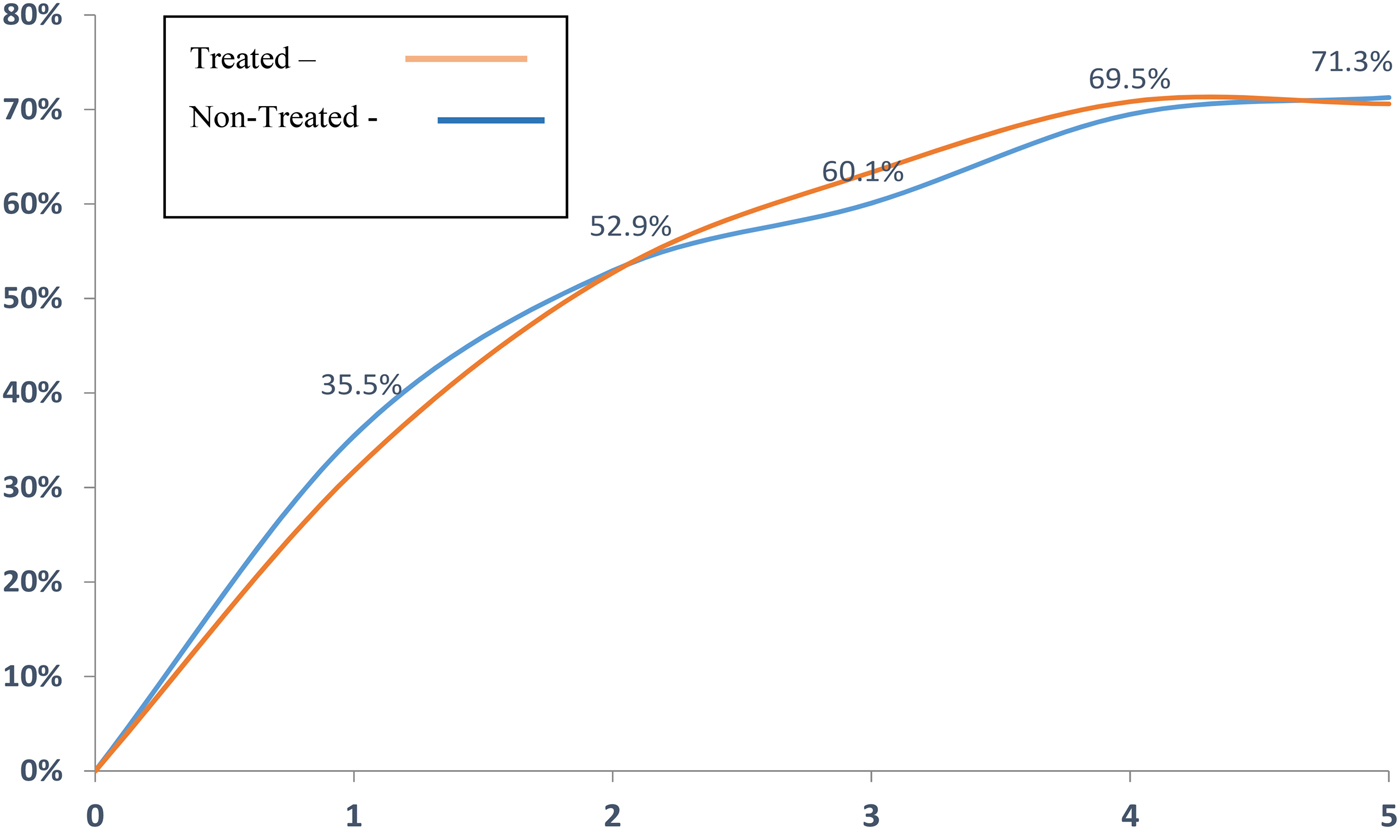

We provide an example of the findings we presented in Figure 2, which compares prisoners in the IPS alcohol treatment programme and the PSM matched comparison group in terms of the cumulative proportion of prisoners re-arrested over five years. This treatment is widely used in the prison service and involves therapeutic and educational components. It is apparent that the treated and untreated subjects demonstrate very similar re-arrest rates over the five-year follow-up period after matching in a PSM model. The results for drug treatment programmes were also discouraging. While providing some examples of significant differences, overall the story remained one of relatively little influence being associated with a programme to which the IPS had attached great importance in its perceived contribution to reducing recidivism.

Figure 2 Cumulative Proportion of Prisoners Re-arrested for the Alcohol Rehabilitation Programme in the Hermon Prison and the Comparison Group (over a Five-Year Follow-up Period)

While the research team expected strong resistance and pushback following the presentation of the findings to the Steering Committee, the opposite occurred. The tone was again set by the Commissioner, who began by emphasising the importance of evidence-based assessments of the rehabilitation programmes for the IPS. In her view the evaluation findings provided important information about the programmes and also aided the IPS in its budget requests to the government. In introducing the findings, the Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team emphasised that their job was not to ‘grade’ the IPS, but to provide information that could be used in developing stronger and more successful programmes.

In some sense, it came as a surprise to both the Research Unit and the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team that the immediate reaction of the Steering Committee was to question what problems may exist in the programmes that would have led to such results rather than the results themselves. Indeed, the tone of the meeting was positive from the outset with researchers, practitioners and members of the Research Unit raising questions and sharing ideas regarding the programmes and reasons why they were not achieving the expected impacts. Over the four years of the study to that point, this was perhaps the most positive indication of the successful institutionalisation of evidence-based policy in the IPS. The Steering Committee related to the results as ‘their findings’ and sought to utilise them to improve programmes in the prison service.

6. The Future of Evidence-Based Policy within the IPS: Challenges and Opportunities

Evaluation evidence provided by the Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team had become a key tool in the decision-making process. In turn, the movement towards evidence-based policy had survived significant changes, including the involvement of three different Commissioners in four years. However, the fourth year of the project also brought significant challenges to the long-term implementation of evidence-based policy in the IPS.

As noted earlier, staffing changes in the Research Unit impeded the development of the policy in the IPS. Two key researchers in the Unit moved to other units (in order to allow for their advancement in the prison service more generally). Such changes greatly reduced the ability of the Research Unit not only to participate in the research process of the grant programme, but also to provide information to the prison service itself. The Commissioner also decided to change the official identification and structure of the Research Unit from a ‘Unit’ to a ‘Branch’. This change was part of a reorganisation in the IPS intended to reduce costs (as a branch would require lower-ranking leadership). However, the change in the definition of the Research Unit to the Research Branch also meant that the rank of the existing commander was too high to continue to lead the unit.

In some sense, this change in the identity of the Research Unit can be attributed to the success of the research programme. The Hebrew University/Ashkelon evaluation team became the central pillar for the introduction of evidence-based policy to the IPS. It provided not just the main technical skills, but also the overall knowledge base for implementation of evidence-based evaluation approaches. Accordingly, the new Commissioner, in reorganising evidence-based practice in the prison service, saw the Hebrew University/Ashkelon team as the key player in advancing the evidence-based policy process in the organisation, and perhaps saw the internal capabilities of the Research Unit as less critical for the advancement of the policy within the IPS.

The full implications of this change are still to be seen. However, there are indications that the institutionalisation of evidence-based science will continue in the IPS. A strong statement of this commitment was made when Commissioner Klinger appointed Dr Kathrine Ben Zvi as Commander of the new Research Branch. Dr Ben Zvi had been one of the original researchers with the Research Unit, and received her PhD in criminology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Criminology. The appointment of a PhD researcher, with a strong commitment to evidence-based policy and experience with implementing evidence-based science in the IPS, represented an important step in the continuity of evidence-based policy in the prison service. More generally, there is much evidence that IPS practitioners have begun to participate in the wider world of science, such as attending national conferences. There is also a clearly growing knowledge of evaluation science in the IPS.Footnote 43

There is the question of whether the IPS will continue to support external evaluations of its programmes once the present research project has ended. The new organisational structure of the prison service seems to identify an external team of researchers as necessary for the development of evidence-based policy within the prison service. However, to date, it is unclear whether this approach will continue in the future.

7. Conclusions

The implementation of evidence-based practices in the IPS, as well as in other settings, is not an inevitable, natural outcome. Rather, as we have highlighted, it is highly dependent on human agency. We have illustrated here how Commissioner Kaniak started the research programme because of his almost serendipitous contacts with research and researchers while he was Deputy Commissioner of the Israel Police. We have also shown how the hierarchical organisation of the prison service enabled future commissioners to work towards the institutionalisation of evidence-based policy by using their hierarchical authority to advance the approach. We have also shown how the introduction of the Research Unit facilitated the efforts of the prison service to take ownership of science. The IPS became a key player in the development of the project and in monitoring its scientific integrity. As Weisburd and Neyroud argue, evidence-based policy should not be imposed from outside an agency; rather, the agency should become a key participant and co-owner of the scientific process.Footnote 44

We have also detailed how the road to evidence-based policy is a ‘winding road’, identifying key turning points along the way that have had an influence on institutionalisation. Our experience also highlights the fact that even with great successes, new challenges emerge. We have detailed those challenges and questions facing the IPS in the continued development of evidence-based policy. We began by quoting a phrase from the Ethics of the Fathers, and we think that researchers and practitioners would benefit from its wisdom. While none of us may be able to bring evidence-based policy to its conclusion in any organisation, and while there may be no ‘end’ to the process, we are not free to abandon our staunch efforts to make evidence-based policy a key part of decision making in criminal justice.