Introduction

More than half a million Canadians live with dementia, and that number is expected to grow to 1,100,000 in 2038, as the baby boomer generation ages (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2010). Many people with dementia (PWD) prefer to receive care at home in the community; in fact, 73 per cent of older adults expect to always live in their current residences (AARP, 2000). Continuing to live at home allows older people to maintain existing social connections, experience greater security and familiarity, and feel more independent (Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve, & Allen, Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). At the same time, receiving care at home can be associated with burden on family caregivers. Family caregivers often endure significantly high levels of stress and emotional and physical burden associated with their caregiving duties (Givens, Mezzacappa, Heeren, Yaffe, & Fredman, Reference Givens, Mezzacappa, Heeren, Yaffe and Fredman2014; Rosler-Schidlack, Stummer, & Ostermann, Reference Rosler-Schidlack, Stummer and Ostermann2011; Vitaliano, Murphy, Young, Echeverria, & Borson, Reference Vitaliano, Murphy, Young, Echeverria and Borson2011).

To reduce the burden on family caregivers of PWD, scientists are developing and promoting the use of innovative technologies, such as assistive technologies and telemedicine (Armstrong, Nugent, Moore, & Finlay, Reference Armstrong, Nugent, Moore and Finlay2010; Lauriks et al., Reference Lauriks, Reinersmann, van der Roest, Meiland, Davies and Moelaert2010). These technologies are designed to address diverse needs in domains, including but not limited to physical health, safety, recreation, and well-being of PWD and their family caregivers. For example, “wandering” technologies can detect if the care recipient is wandering from home during the night, and can automatically warn caregivers so that they can have better quality sleep without the need for constant monitoring, and supervision systems allow family caregivers to monitor the care recipient’s activities from a distance. Nevertheless, gaps between the needs of family caregivers and new technologies still exist because of incorrect understanding of the needs and challenges of people living with dementia who are also the technology users (Wherton & Monk, Reference Wherton and Monk2008). Some researchers have pointed out (Miranda-Castillo, Woods, & Orrell, Reference Miranda-Castillo, Woods and Orrell2010) that the needs of family caregivers may not be effectively communicated to health care providers. Misunderstanding may lead to caregiver needs being ignored and unsupported, which may leave family caregivers with more challenges from within the health care system.

The purpose of this study was to explore how family caregivers of PWD living at home use technology to meet their needs. Conducting a descriptive comparison between family caregivers and health care providers, we aimed to identify the important, unmet needs of family caregivers of PWD living at home, to investigate family caregivers’ specific experience with technology use to assist them with their dementia care tasks, and to examine health care providers’ understanding and knowledge of family caregivers’ needs and technology use.

Literature Review

Needs of Family Caregivers

Family caregivers play a critical role in all stages of care for PWD, including diagnosis, treatment, symptom management, and placement (Dupuis, Epp, & Smale, Reference Dupuis, Epp and Smale2004). Care responsibilities are often lengthy in duration, variable across time, and cumulative as dementia symptoms progress (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Epp and Smale2004). Therefore, family caregivers are often challenged with physical and psychosocial problems: they visit health care professionals more frequently, have more health problems, and use more medication than other people of their age (Butler, Reference Butler2008; Eagles et al., Reference Eagles, Craig, Rawlinson, Restall, Beattie and Besson1987; Keating, Fast, Fredrick, Cranswick, & Pierre, Reference Keating, Fast, Fredrick, Cranswick and Pierre1999; Pot, Deeg, & Van Dyck, Reference Pot, Deeg and Van Dyck1997).

Given the intensive nature of the dementia caregiving role, family caregivers have complex needs in diverse domains. Recent studies found that family caregivers reported multiple needs around providing care for PWD, with key domains including information about dementia and services, emotional support, access to formal services, assistance with care tasks and activities of daily living, and financial and legal assistance (Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant, & Sanson-Fisher, Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017; McCabe, You, & Tatangelo, Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016). The degree to which needs are met is crucial not only for the well-being of family caregivers (Costanza et al., Reference Costanza, Fisher, Ali, Beer, Bond and Boumans2007), but also for PWD to receive high quality of care at home. Although many studies focus on needs assessment for the purpose of implementing targeted clinical support (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017), few studies have shed light on whether the needs can be met by either current health care and social care services or technology use. Therefore, in contrast to studies aiming to identify caregiver needs more generally (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016), this work targets the important, yet unmet needs that can be addressed through dementia care technologies.

Technology Use Studies

Technology has the potential to address many of the needs of PWD and their family caregivers. Various types of technologies are widely used in health care, such as assistive technologies, telemedicine, eHealth, medical devices, and electronic medical records. In this study, we focus on three groups of commonly adopted technologies: (1) assistive technologies, (2) telemedicine, and (3) social media (Czarnuch, Ricciardelli, & Mihailidis, Reference Czarnuch, Ricciardelli and Mihailidis2016). For family caregivers, technology can help provide emotional support, training, and education, and can facilitate coordination of care with professionals (O’Connell et al., Reference O’Connell, Crossley, Cammer, Morgan, Allingham and Cheavins2014; Topo, Reference Topo2009). Technology can also decrease care tasks of family caregivers by increasing PWD’s independence in performing daily activities, self-managing their health, keeping themselves safe, and delivering psychosocial therapy (Barlow, Singh, Bayer, & Curry, Reference Barlow, Singh, Bayer and Curry2007; Ekeland, Bowes, & Flottorp, Reference Ekeland, Bowes and Flottorp2010; Topo, Reference Topo2009).

Effective technological solutions need to be matched to current needs (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Barlow, Comas-Herrera, Damant, Freddolino and Hamblin2015). Most mainstream technology studies primarily examine functions of technology and user experience (Asghar, Cang, & Yu, Reference Asghar, Cang and Yu2015; Godwin, Mills, Anderson, & Kunik, Reference Godwin, Mills, Anderson and Kunik2013; Lauriks et al., Reference Lauriks, Reinersmann, van der Roest, Meiland, Davies and Moelaert2010). Lauriks and colleagues (Reference Lauriks, Reinersmann, van der Roest, Meiland, Davies and Moelaert2010) conducted a study to identify the gaps between technologies and identified needs. Evaluating information and communication technology-based services for the needs of people with mild-stage dementia, the authors pointed out that demand-oriented, personalized information is still difficult to obtain, and that support for coping with behavioural and psychological changes in dementia is relatively insufficient (Lauriks et al., Reference Lauriks, Reinersmann, van der Roest, Meiland, Davies and Moelaert2010).

There is a growing interest in studying technologies that incorporate principles of user-centred design to fulfill users’ needs. In 2016, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) published a comprehensive report on how caregivers use currently available technologies, what functions they are interested in, and barriers to using technologies (AARP, 2016). This report focused on health needs that could be fulfilled by available technology, without much discussion of other types of unmet needs, such as social needs or emotional needs. In Canada, some researchers have shed light on how assistive technology may help family caregivers by decreasing their burden (Mortenson et al., Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and DeRuyter2012). Mortenson and colleagues (Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and De Ruyter2015) developed a tool (the Caregiver Assistive Technology Outcome Measure), to study the contribution of assistive technology usage to reducing indices of burden experienced by family caregivers. Using this tool, a randomized controlled trial confirmed that the usage of assistive technology can significantly reduce caregiver burden, such as the physical strain of providing care or concerns about care recipient accidents or injuries (Mortenson et al., Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Bilkey and Plante2018). This research contributes to the development of the literature on technology use in health care. However, their inclusive approach to technology interventions for various diseases provides little information about technology use in the specific field of dementia care, in which family caregivers are facing a unique set of challenges, such as unpredictable progression of symptoms. Here we focus on family caregivers of PWD, who often demonstrate higher levels of unmet needs and lower levels of service utilization (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016), with the purpose of understanding how technology can be utilized to address these needs to more effectively support family caregivers and care recipients living with dementia.

Perspectives of Health Care Providers

In addition to technology, family caregivers need to be provided with adequate resources from the available health care services to cope with their caring tasks and increasing responsibilities in response to progressive health declines in the care recipient experiencing dementia (Van Mierlo, Meiland, Van Der Roest, & Dröes, Reference Van Mierlo, Meiland, Van Der Roest and Dröes2012). Sometimes health care providers play the role of opinion leaders and recommend technologies to family caregivers to better assist their care tasks (Lauriks et al., Reference Lauriks, Reinersmann, van der Roest, Meiland, Davies and Moelaert2010; Meiland et al., Reference Meiland, Innes, Mountain, Robinson, van der Roest and García-Casal2017). However, the recommendation will only be successful when health care providers are sufficiently aware of the needs of family caregivers and are knowledgeable about how specific technologies can meet their needs. Without a good understanding of family caregivers’ needs, health care providers’ support may be inefficient, and will consequently result in ineffective care or support for PWD.

The perspective of frontline care providers, such as personal support workers (PSWs) who provide 70–80 per cent of the paid home care services in Canada, including services for PWD living at home (Afzal, Stolee, Heckman, Boscart, & Sanyal, Reference Afzal, Stolee, Heckman, Boscart and Sanyal2018), is especially relevant, and can potentially inform whether there are unmet needs. An accurate perception of health care providers regarding unmet needs of family caregivers can contribute to improvements in quality of care through directing adoption of new technology, development of new policies, or educational programs for health care providers.

The few reports in the literature examining the difference between caregivers’ perceived needs and health care providers’ assessment of their needs indicate that the latter tend to overestimate the unmet needs of caregivers (Cohen-Mansfield & Frank, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Frank2008; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016). In regards to the domains of needs being examined, Cohen-Mansfield and Frank (Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Frank2008) looked at health-related needs, including health and function, mental health, sensory function, and health behaviours, whereas Orrell and coworkers used a comprehensive list of the needs of older adults (Orrell et al., Reference Orrell, Hancock, Liyanage, Woods, Challis and Hoe2008). Both studies evaluated whether the needs were met by the health care system. These studies suggest that with the wider adoption of technology in the field of health care, it is necessary to examine whether technology use, as a substitute for or extension of care services provided by health care institutions, can fulfill not only health needs, but also the informational and social needs of family caregivers of PWD.

To address the gaps in the literature, we adapted existing surveys in the field to create two comparable versions of The Dementia Caregiver Needs Questionnaire, one for family caregivers and one for health providers, with the purpose of answering three research questions.

(1) What are the important, unmet needs of family caregivers?

(2) How do family caregivers use technology to assist with their care tasks?

(3) What do health care providers know about family caregivers’ needs and technology use?

We chose a quantitative, survey-based method for three reasons. First, items could be designed to correspond across the two versions of the survey to facilitate comparison of overall opinions of family caregivers and those of health care providers. Second, the survey administration could be flexible, in either online or paper mode, depending on respondent preferences, with the online option increasing the reach of the study. Third, the survey method permits access to larger sample sizes (Jones, Baxter, & Khanduja, Reference Jones, Baxter and Khanduja2013), and we intended to collect data from a sample that was large enough to be representative.

Methods

Participants

Family or friend caregivers of PWD (n = 33) and health care providers (n = 60) working with PWD living at home were eligible for the study. Participants were provided with the survey link on SurveyMonkey or a printed copy with a postage prepaid envelope.

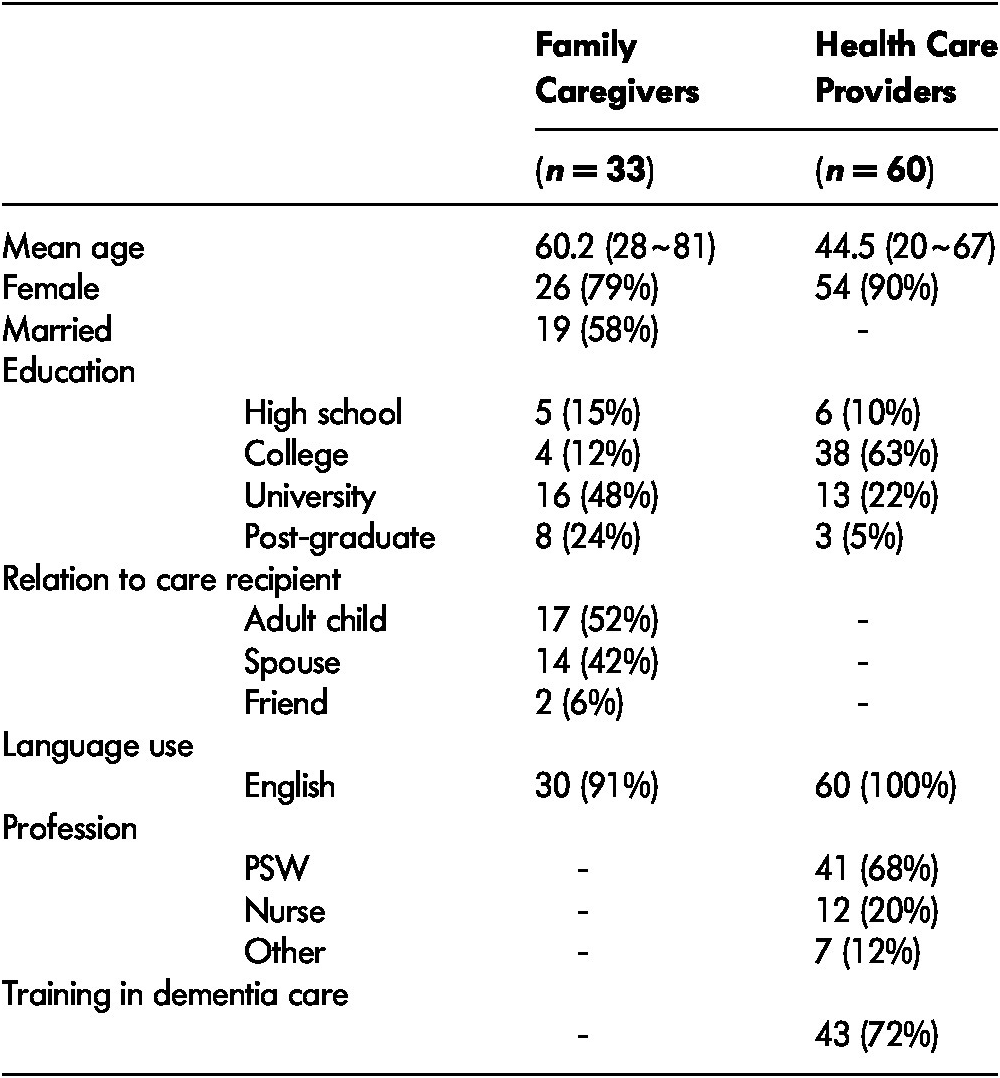

The mean age of the participants who are family caregivers was 60.2, and 79 per cent were female, which is slightly higher than the percentage of female caregivers in Canada (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Epp and Smale2004).The participants are well educated, with 72 per cent of them having a university or postgraduate degree. Over half (52%) of family caregivers are taking care of a parent, and 42 per cent are taking care of a spouse (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants

Note. PSW = professional support worker.

The average age of PWD who are receiving care from family caregivers was 76.9. Most (94%) of the care recipients had received a formal diagnosis of dementia; of these, 52 per cent had been diagnosed with dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Most PWD started to show dementia symptoms 3–5 years prior to the study period.

For health care providers who responded to the survey, the mean age was 44.5. Among them, 90 per cent are female, 68 per cent are PSWs who provide care to PWD in their homes, with other participants in various professions. Nearly three quarters (72%) of the participants have received training in dementia care (Table 1).

Measures

The survey for family caregivers consisted of questions in multiple sections, such as demographic information on the PWD and their caregivers, caregivers’ needs in providing care at home, their communication and interaction with health care providers, their experiences with innovative care technologies, and their social support networks. The survey for health care providers consisted of questions on their perceptions of family caregivers’ needs, their communication with family caregivers and PWD, their opinions and use of technology in dementia care, and their professional networks.

The Dementia Caregiver Needs Questionnaire was constructed using five distinct need domains identified from previous checklists: information needs, emotional and self-care needs, care task needs, formal service needs, and legal/financial needs (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Anderson, Leach, Smith, Schmitt and Mendiondo2004; Keefe, Guberman, Fancey, Barylak, & Nahmiash, Reference Keefe, Guberman, Fancey, Barylak and Nahmiash2008; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017; Vaingankar et al., Reference Vaingankar, Subramaniam, Picco, Eng, Shafie and Sambasivam2013; Wancata et al., Reference Wancata, Krautgartner, Berner, Alexandrowicz, Unger and Kaiser2005). We also included three items assessing the need for understanding from others about dementia caregiving, to measure opinions around dementia-related stigma. The measure included 38 total needs across these six domains: (1) information (Need 1-7), (2) emotional support and self-care (Need 8-15), (3) care tasks (Need 16-25), (4) formal care (Need 26-33), (5) financial and legal assistance (Need 34-35), and (6) understanding from others (Need 36-38) (See Appendix 1). Participants rated the importance of each need on a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). They also indicated the degree to which the item had been met in the past 12 months, with response options including no need, unmet need (1), partially met need (2), or met (3) need. Scores for the latter three options were averaged across needs to give an overall indication of the degree to which each need domain was met. The overall internal reliability of the needs measure was strong (Cronbach’s α = 0.96). Formal caregivers received the same questionnaire items; however, they were asked to judge the importance of each need to family caregivers of people with dementia, and indicate the degree to which each need was met in the current health care and social services systems.

The technology use by family caregivers measure focuses on the use of 21 types of assistive technologies, telemedicine, and social media by family caregivers for dementia care (see Appendix 2). We used a list of technologies adapted from Czarnuch et al. (Reference Czarnuch, Ricciardelli and Mihailidis2016), asking about ownership and frequency of use, as well as participants’ opinion of the usefulness of each item. Additional emerging technologies were added relevant to health care (e.g., virtual visits to health care providers), emotional support (e.g., remote psychotherapy), social connections (e.g., social media), and cognitive/leisure activities (e.g., brain training games). Caregivers indicated whether they owned each technology type, and if so, how often they used it (daily, weekly, monthly, every 6 months, every 12 months, or not at all). They also rated how useful each technology was perceived from 0 (not at all useful) to 10 (extremely useful). Formal caregivers also rated the perceived usefulness to them of each technology type for dementia care, and indicated whether they had ever recommended that type of technology to their clients.

Caregiver burden was measured using the 12-item version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) (Bédard et al., Reference Bédard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater burden. Participants also rated from 1 to 10 how stressed they felt related to their caregiving role. Functional ability of PWD was rated by participants using the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS) (Bucks, Ashworth, Wilcock, & Siegfried, Reference Bucks, Ashworth, Wilcock and Siegfried1996), a validated measure used in previous studies (e.g., Czarnuch et al., Reference Czarnuch, Ricciardelli and Mihailidis2016). Scores ranged from 0 (totally independent) to 60 (totally dependent).

Access to service was measured using a 29-item list of currently available health care and social services in Canada. Caregivers indicated whether they had access to each service (1 for yes and 0 for no). An overall access score was calculated by summing scores of all items.

Size of social network was a continuous variable. Family caregivers were asked to report how many connections they have for each category of family, friends, coworkers, neighbors, and other relationships. Size of social network was calculated from the total number of the connections.

We also included five continuous variables to understand the context and experience of participants: family caregiver’s age, care recipient’s age, care recipient’s years of dementia symptoms, health professional’s age, and health professional’s years of experience in dementia care.

Analysis

We conducted four analyses. First, we described caregiver needs and technology use behaviour and attitude using mean scores and percentages. Second, we revealed association among variables using correlation analysis. Third, we conducted linear regression analysis to further understand the factors that contributed to technology use behaviour. Finally, to compare various groups’ opinions on the same items, such as importance of needs, importance of technology, usefulness of technology, we used mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

Important Needs of Family Caregivers

As the needs of family caregivers of PWD have been identified in the literature (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016), it is reasonable to consider that all the needs are somewhat important. In fact, the average importance score of all the needs reported by family caregivers is 7.7, indicating that family caregivers tend to believe that all the needs are fairly important to them.

Among the six groups of caregiver needs, understanding has the highest mean importance score, with the mean (M) of 8.3 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.1). The second most important category is financial and legal assistance (M = 8.0, SD = 2.6). The least important category is care tasks (M = 7.3, SD = 2.3). Although this value is slightly lower than the overall mean importance of all needs, it still confirms the importance of the needs in this group for family caregivers.

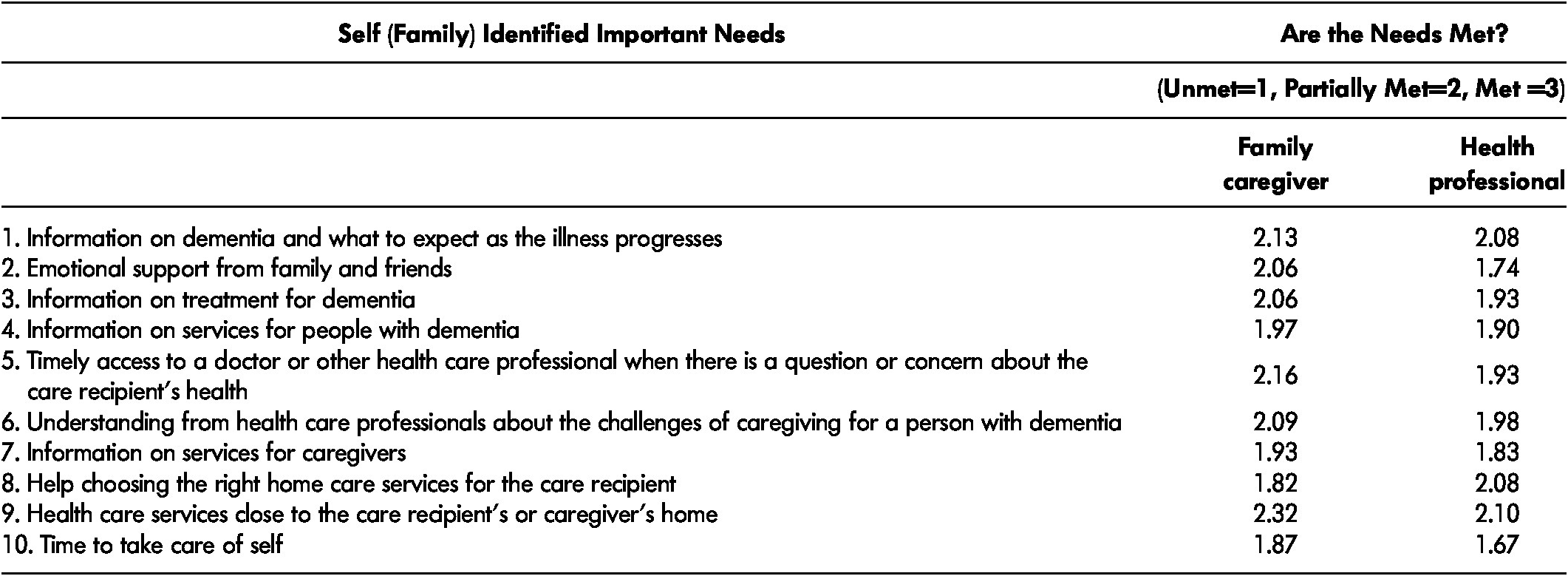

To further tease out the important, unmet needs, we focus on 10 specific needs whose mean scores of importance are at or above the 75th percentile (8.4) of the mean importance score of all needs (Table 2). Four items belong to information needs; three are needs for formal support, two are needs for emotional support and self-care; and one a need for understanding.

Table 2: Most important needs for family caregivers and whether they are currently met according to family caregivers and health care providers

Family caregivers deemed three needs as unimportant: (1) information that is easier to understand or is given in another language, (2) services that cater to the care recipient’s and/or the caregiver’s ethnic or cultural background, and (3) help with making decisions and managing conflicts with other family and friends involved in caring for the care recipient. The relative unimportance in the first two needs can be explained by the fact that 90 per cent of the participants speak English as the primary language.

In addition to the importance of each of the specific needs, we also ask family caregivers whether the needs for family caregivers are unmet, partially met, or met (the value ranges from 1 to 3). On average, 20 per cent of family caregivers gave a score of 1 across six need groups, which suggested they had unmet needs; whereas 36 per cent of participants reported unmet needs for financial and legal assistance and 33 per cent reported unmet needs for understanding as well as therapy to manage stress, depression, and anxiety. Accordingly, the mean scores for financial and legal assistance, understanding, and care tasks are lower than the other three groups of needs, which indicates that these needs are less well met. The need for information in general is better met than other groups of needs.

Among the 10 important specific needs, family caregivers identified four unmet needs: help choosing the right home care services for the care recipient, time to take care of self, information on services for caregivers, and information on services for PWD. These needs are in the domains of information, formal support, and emotional and self-care. Eighteen out of 38 items were reported to be lower than 2, which is the value for “partially met” needs. The lowest ranking of an unmet need was for financial assistance. In additional, five of the unmet needs are related to care tasks and four are related to formal support.

Individual Differences in Caregivers’ Needs

To identify factors that are associated with the importance of needs and the degree to which needs are met, we conducted a Pearson’s correlation analysis. Family caregivers reported a moderate level of stress from care responsibilities; the mean burden score was 25.5 (SD = 8.9; short Zarit Burden Interview [ZBI] Bédard et al., Reference Bédard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001) out of 48, and the mean self-reported stress level was 6.6 (SD = 2.2) out of 10. Self-reported stress of family caregiver was positively associated with the importance of emotional support (r[30] = 0.40, p < 0.05), formal support (r[30] = 0.47, p < 0.01), and financial and legal assistance (r[30] = 0.45, p < 0.05), while it was also highly negatively correlated to the degree to which the need for emotional support was met (r[31] = -0.61, p < 0.001). Family caregivers’ burden score was also negatively associated with the degree to which the need for emotional support was met (r[31] = -0.64, p < 0.001). These results suggest that caregivers with increased stress and care burden are more likely to have unmet emotional support needs.

Finally, family caregivers’ size of social networks was positively associated with the degree to which the need for emotional support was met (r[31] = 0.43, p < 0.05). The larger networks family caregivers had, the better their emotional needs were supported.

Technology Use by Family Caregivers

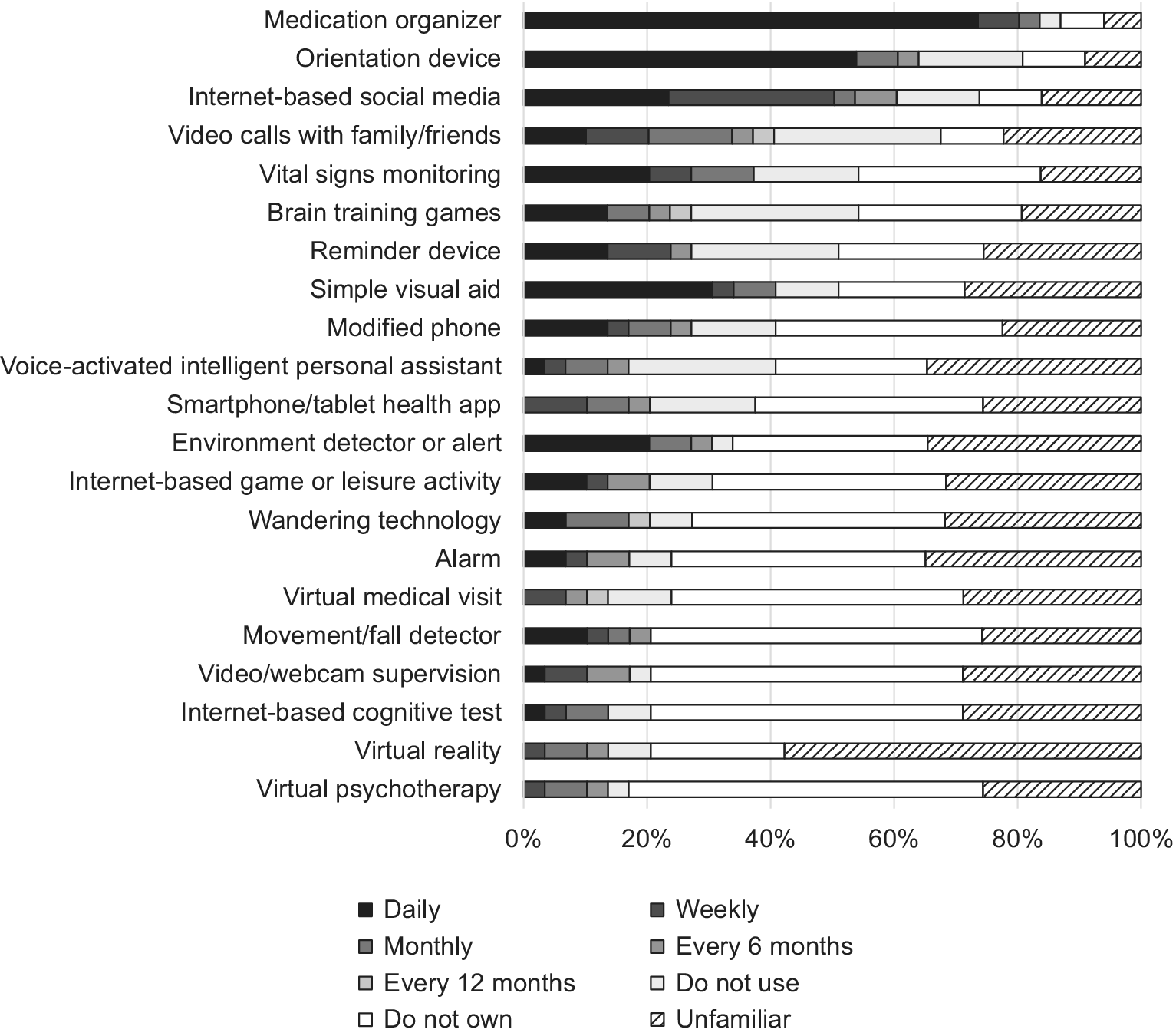

On average, family caregivers reported having eight types of technologies to help in their caregiver role, but the variance was rather high (SD = 6.0). The most commonly used technologies were medication organizers or reminders and orientation devices, which were owned by more than 80 per cent of participants. Other than these two technologies, social media, video calls to communicate with family and friends, in-home monitor of vital signs and other health indicators, brain training games, reminder systems, and simple visual environment aids were owned by more than half of the family caregiver participants. The least available technology was psychotherapy or counselling delivered remotely online (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Family caregivers’ technology ownership and use

Given that our technology use measure included many recent, emerging technologies, family caregivers were unfamiliar with several of these items. There were 14 technologies (67% of all technologies) about which more than a quarter of the participants said that they did not know whether these technologies were useful. The technology associated with the lowest familiarity was virtual reality: more than 50 per cent of family caregivers were unable to judge its usefulness (Figure 1).

Ownership is related to frequency of technology use. It stands to reason that people who own technology may use it more frequently. Meanwhile, frequency of technology use is also predetermined by the functionality. For example, “wandering” technology might be in use 24/7, whereas remote visit to a doctor might be used weekly or monthly.

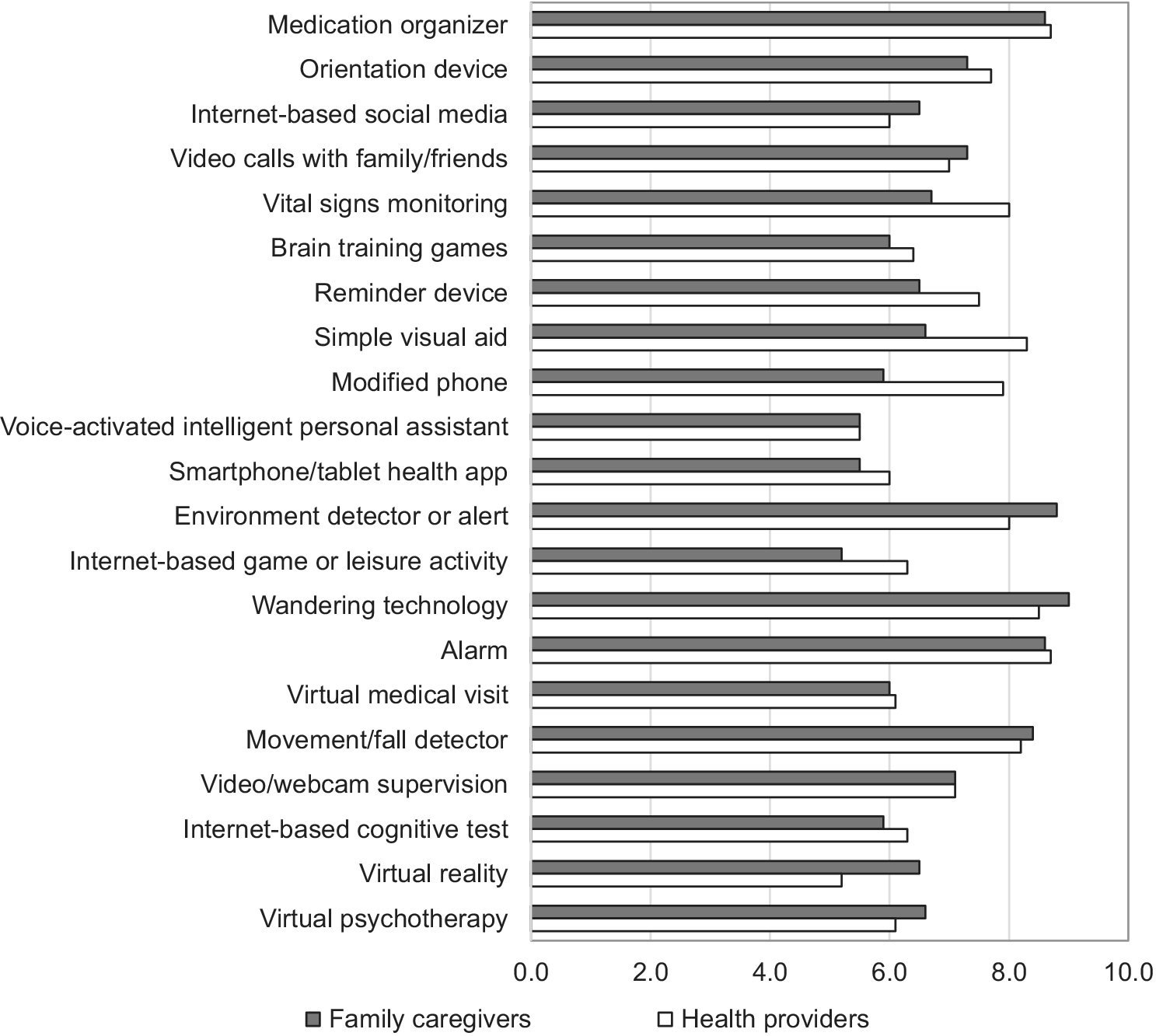

For technology usefulness, family caregivers provided positive responses: all technologies were useful in general, but at varying levels. The most useful technologies were: (1) “wandering” technology, (2) environment detectors or manipulators, (3) medication organizers or reminders, (4) alarm or pager units, and (5) movement or fall detectors. Despite the high usefulness score, only one useful technology, medication organizers or reminders, was commonly owned by family caregivers (87%). Less than 35 per cent of family caregivers owned any of the other four useful technologies.

Technology owners and non-owners may have different opinions about the usefulness of certain technologies because of the differences in their real experience with the technologies. Using t tests to compare the usefulness scores reported by owners and non-owners, we found that these two groups shared similar opinions, except about one specific technology: owners of a device for in-home monitoring of vital signs and other health indicators considered the technology to be highly useful, whereas non-owners considered it significantly not useful (t[23] = 2.5, p = 0.02; Figure 2).

Figure 2: Family caregivers’ and health care providers’ perceptions of the usefulness of technologies

To explore and identify factors that were associated with family caregivers’ use of technologies, we examined the correlation among ownership, frequency of use, importance of technology, and other predictors. We found that number of technologies owned was negatively associated with age of family caregivers (r[31] = -0.40, p < 0.05) and age of care recipients (r[30] = -0.53, p < 0.01). This suggests that family caregivers or care recipients who are older own and use fewer technologies than those who are younger.

Conversely, frequency of technology use was positively associated with caregiver’s age (r[31] = 0.60, p < 0.01) and care recipient’s age (r[30] = 0.65, p < 0.001). This suggests that family caregivers or care recipients who are older are more likely to use technologies that require frequent use, such as medication organizers, than those who are younger. Using a regression analysis to further examine predictors of frequency of technology use (R2 = 0.66), the results show that caregiver’s age was positively associated with frequency of technology use (β = 0.41, p < 0.05), and access to healthcare services had a stronger positive effect (β = 0.44, p < 0.01), whereas caregiver’s stress (β = -0.46, p < 0.05) and number of technology owned (β = -0.39, p < 0.05) had significantly negative effects on frequency of technology use.

To further understand family caregivers’ attitudes towards technology, we focused on technology use for communication purposes. Among family caregivers, 74 per cent used social media and 68 per cent used video calls to communicate with family, friends, and other community members. Furthermore, 90 per cent of family caregivers reported that they often used the Internet to get information about dementia or dementia-related resources. This percentage is much higher than the second source of information about dementia, which is through a care provider (70%). The third source is through health media (50%).

Other than proactively using the Internet to obtain information about dementia and dementia-related resources, family caregivers also showed a rather open attitude towards communicating with health care providers via technology. When asked their opinion on the statement “I am comfortable talking to health care providers in person instead of over the phone or Internet,” approximately half of the participants indicated disagreement or neutrality. The average score of attitude also consistently showed that family caregivers are not against the option of communicating via technology.

Health Care Providers’ Perceptions

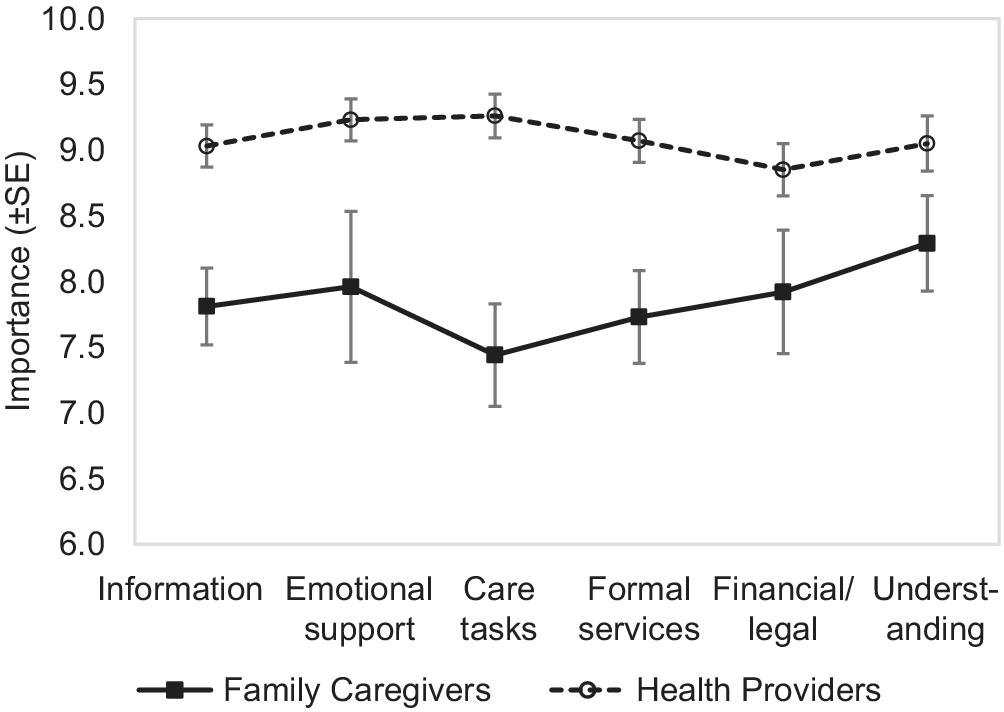

We examined health care providers’ opinions on the importance of the needs of family caregivers and asked them to rate whether the needs were met. Importance ratings were compared across groups using a 2 (group: family caregivers, health professionals) × 6 (needs type: information, emotional support, care tasks, formal services, financial/legal, understanding) mixed ANOVA with repeated measures on the second variable. Greenhouse–Geisser adjustments for degrees of freedom are reported where appropriate. In general, health care providers gave higher importance to the score of needs than family caregivers (F[1,88] = 16.60, p < 0.001). There was no main effect of need type (F[3, 282] = 1.42, p = 0.22). There was a significant group × needs interaction, (F[3,282] = 4.60, p = 0.003), indicating that the relative importance of needs differed between groups. In particular, health care providers rated care tasks (9.26) as the most important need, which was substantially higher than the importance score rated by family caregivers (7.33). For family caregivers, the needs for care tasks had the lowest importance score (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Importance of needs for family caregivers and health care providers

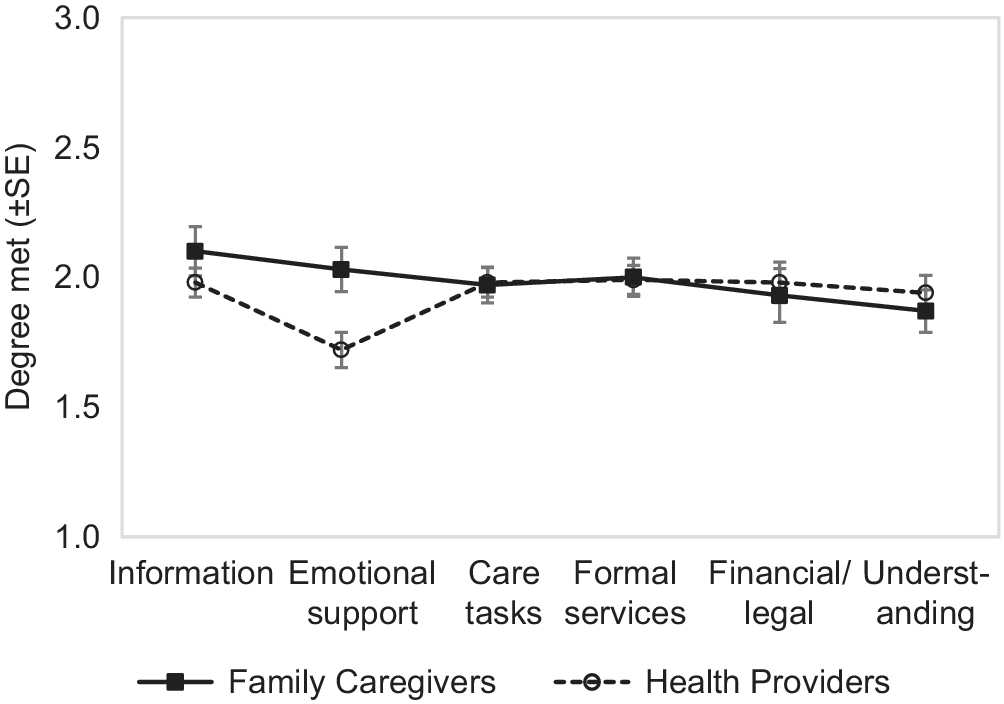

Ratings on whether needs were met were also entered into a 2 (group) × 6 (needs type) mixed ANOVA. There was no overall difference between family caregivers and health care providers (F < 1). A main effect of needs type (F[4,348] = 3.57, p = 0.004) was qualified by a significant group × needs type interaction (F[4,348] = 3.34, p = 0.01). In particular, health care providers had more pessimistic ratings about whether emotional needs of caregivers were met (see Figure 3). Particularly for emotional support and self-care, family caregivers reported that this group of needs was partially met, but health care providers gave this item the lowest rating (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Degree to which needs are met for family caregivers and health care providers

Breaking down health care providers’ opinions into 38 specific needs, we observed some discrepancies between health care providers and family caregivers. For the 18 specific needs that were rated as unmet by family caregivers, health care providers reported that help coordinating and organizing the care that the care recipient is receiving, help choosing the right home care services for the care recipient, and information on planning for the future were partially met (Table 2).

Health care providers shared the opinions of family caregivers towards technology usefulness. In fact, we observed a high level of correspondence between the opinions of these two groups (Figure 2). However, the opinions towards three types of technologies were different. Family caregivers gave less importance to environmental aid (6.6), a phone with modification for the care recipient (5.9), and in-home monitoring of vital signs and other health indicators (6.7), whereas health care providers gave these significantly higher scores.

Finally, health care providers’ perception about family caregivers’ attitudes towards using technology for communication with them was significantly different than caregivers’ responses (t[83] = 5.5, p < 0.001). Health care providers believed that family caregivers preferred to communicate in person versus via technology.

Discussion

This study was an exploratory investigation to understand how family caregivers of PWD used technology to cope with care tasks and increased difficulties at home. We developed a comprehensive survey called The Dementia Caregiver Needs Questionnaire to study the experiences and opinions of both family caregivers and health care providers. We identified the important, unmet needs of family caregivers, revealed family caregivers’ technology use behaviour and attitudes among family caregivers, and recognized differences in opinions towards various needs and technology between family caregivers and health care providers.

In summary, the important, unmet needs reported by family caregivers are in the domains of information, formal support, emotional and self-care, and understanding. These needs are dependent on caregivers’ levels of stress, perceived burden, access to health care services, and social networks. Those who were more stressed with heavier burden tended to feel that their needs for emotional support were unmet. Larger social networks can provide family caregivers with more emotional support.

Many family caregivers neither own emerging technologies, nor are they familiar with these technologies. Nevertheless, both technology owners and non-owners considered technology to be useful in general. Family caregivers primarily used technologies to help manage medication, keep care recipients safe from environment hazards, provide care recipients with cognitive assistance, and communicate with family and friends.

There were some differences in perceived family caregiver needs between the family caregivers and health care providers, particularly in the domains of care tasks and emotional support. There was also a gap in perceived family caregiver attitudes towards communication via technology: family caregivers were open to communicate with health care providers via technology; health care providers, despite their optimistic opinions on technology usefulness, believed that family caregivers were more resistant to use of technology for communication.

Our results suggest that currently available technologies are not successfully supporting family caregivers to accomplish their dementia care tasks. Family caregivers, in general, have limited access to the majority of the technologies. In particular, caregivers who are older adults have even fewer technologies at home. This result is consistent with other technology studies with older populations (Cotten, Anderson, & McCullough, Reference Cotten, Anderson and McCullough2012; Smith, Reference Smith2014). Therefore, lack of ownership is the first barrier to technology use for dementia care. However, our findings prove caregivers’ willingness to use technology to support their care roles. Older adults are not heavy users of technology, but they might be dependent on one or two tools, such as medication organizers, on a daily basis; 90 per cent of family caregivers use the Internet to search for dementia-related information; those who use technology more frequently have more access to health care services; and family caregivers indicated an amenable attitude towards communicating with health care providers via technology.

Our work contributes to the study of family caregivers of PWD in three ways. First, this study used an exploratory approach to investigate the needs of family caregivers. We identified important, unmet needs and explored the factors that contribute to the occurrence of these needs. In the literature, caregiver needs have been primarily identified using qualitative analysis of structured research interviews; several quantitative checklists of caregivers’ needs have been developed, but these measures are lacking in some indicators of psychometric rigour (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017). We believe that our exploratory approach with a survey questionnaire can provide a mechanism to perform more rigorous quantitative analyses of caregiver needs.

Second, we revealed the gaps in perceptions between family caregivers and health care providers. Although health care providers seem to be more knowledgeable and better trained to care for people in various phases of dementia, they do not necessarily understand the needs of family caregivers or the degree to which needs are met by current health care and social service systems (Cohen-Mansfield & Frank, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Frank2008; Orrell et al., Reference Orrell, Hancock, Liyanage, Woods, Challis and Hoe2008). Their understanding of family caregivers’ attitudes towards technology use in general is also overly pessimistic. As the top source of dementia-related information, technology-based resources are clearly relied on by family caregivers. Underestimations of family caregivers’ interest in using technology may inhibit the implementation of new care models using technology, thereby preventing potential improvements in quality of care.

Third, our findings revealed the importance of formal care, informal social support, and technology use in a complex care circle in which family caregivers are embedded. We argue that family caregivers of PWD can be better supported by easier access to formal health care and social services, active engagement in large social networks, and some use of assistive technology, particularly for communication. As family caregivers are open to using technology to receive service from health care providers and they own technologies to connect with members in their own social networks, we see significant potential in using technology to support older adults in the caregiving role at home. Existing studies have revealed positive impacts of caregivers’ technology use on their burden (Mortenson et al., Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and DeRuyter2012, Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and De Ruyter2015, Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Bilkey and Plante2018). The findings presented here extend this past research to identify which unmet caregiver needs these technologies should address.

A number of studies have examined the needs of family caregivers of PWD (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Boyes, Bryant and Sanson-Fisher2017; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016) and the use of technology to decrease caregiver burden (AARP, 2016; Mortenson et al., Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and DeRuyter2012, Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Lenker and De Ruyter2015, Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Bilkey and Plante2018). This study adds to the existing literature by focusing on unmet needs and linking these to caregivers’ existing technology use and/or willingness to adopt technology, with the purpose of informing how technology can be leveraged to address these unmet needs.

There are some important limitations of the research presented here. First, the study was conducted with a limited population, and replication with a broader Canadian sample is needed to determine the reliability of the findings. Second, factors such as the duration and frequency of caregiving activity, the severity of dementia in the care recipient, and the nature and quality of the interpersonal relationship between care recipient and caregiver, were not evaluated. Past research indicates that these factors may exert important moderating influences on unmet caregiver needs (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016; Mortenson et al., Reference Mortenson, Demers, Fuhrer, Jutai, Bilkey and Plante2018) and should be considered in future studies investigating the role of technology in meeting these needs.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000094.