Deliberation, in the sense of elevated discussion (roughly, an open-minded weighing of the arguments and evidence for and against competing alternatives), is generally seen as enhancing democracy (Bohman and Rehg Reference Bohman and Rehg1997; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2002; Elster Reference Elster1998; Fishkin Reference Fishkin1991) – perhaps most centrally by refining the ‘public will’ that democracy translates into policy choices. The participants acquire a better sense of what policies they should favor, in light of their own values and interests, moving their policy attitudes toward those they would hold with the benefit of unlimited information and thought.Footnote 1 This effect stems from deliberation's defining properties, those making it more than just any discussion.

But discussions also have non-deliberative effects, products of their social dynamics. These may plausibly lead a deliberating group's participants to: (1) converge on the same attitude (what we shall term homogenization), (2) adopt more extreme attitudes on whichever side of the issue the group started on (commonly termed polarization), or (3) adopt attitudes closer to those of their more socially advantaged (male, better-educated, more affluent) co-deliberators (to be termed, more hesitantly, domination). These are all varieties of group-level attitude change – as distinct from their sources and consequences, a point particularly worth stressing for ‘domination’, which in other, nearby usage (for example, Squires Reference Squires2008) denotes underlying dialogic inequalities. Here it simply means attitude change toward the attitudes of the advantaged.

A widely held, if not always fully articulated, concern about these particular attitude changes is that they may be mostly away from the attitudes the participants would hold with the benefit of unlimited information and thought.Footnote 2 They are, in that case, our title's ‘distortions’. Discussions routinely producing them would be warping rather than refining the public will. But, as the title's punctuation suggests, this leaves some questions. To what extent do these putative distortions actually prevail? And to what extent is it the deliberation in the discussion that produces them – making them deliberative distortions?

Here we tackle these questions with data from twenty-one Deliberative Polls (DPs), on various issues, in various contexts, encompassing 2,601 group-issue pairs. The core empirical analysis addresses the first question directly and affords inferences addressing the second. For these purposes, size (the dataset's) matters. Any one group, discussing any one issue, in any one context, may or may not exhibit homogenization, polarization, or domination, no matter what the discussion is like. It is the distributions across groups, issues, and contexts that are revealing. We preface this analysis by laying out the underlying theory and follow it by considering nuances, possible objections, and implications for deliberative design.

The Conceptual Terrain

We begin by sketching some key concepts.

Deliberation, Policy Attitudes, and Associated Cognition

Deliberation

What lifts deliberation above mere discussion is its being (1) substantive, (2) inclusive, (3) responsive, and (4) open-minded. That is: (1) the participants exchange relevant arguments and information. (2) The arguments and information are wide-ranging in nature, and the policy implications neither all of one kind nor all on one side. (3) The participants react to each other's arguments and information. And (4) they seriously and even-handedly (re)consider, in light of the discussion, what their policy attitudes should be. In short, deliberation requires that its participants engage in a serious, open-minded, even-handed weighing of the merits.Footnote 3 It does not require consensus-seeking or conscious, collective decision-making (cf. Cohen 1989; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004). It may or may not yield a consensus. It may but need not affect subsequent decision-making by other bodies (as many DPs have done). It may even – optionally – involve conscious, collective decision-making itself, although that may alter the discussion's effects, in ways we consider below.

Realistically, ‘deliberation’ is not a discrete property – something that does or does not occur – but the high end of a continuum (Fishkin Reference Fishkin1991). Some discussions are highly deliberative, others hardly at all. The unattainable top of the range is something like Habermas's (Reference Habermas, Benhabib and Dallmayer1990) ‘ideal speech situation’: a thought experiment in which every argument is made and countered, and in which everyone weighs all the arguments and counterarguments, free of all coercion. The bottom is vacuity: nobody says anything of substance. In these terms, the great majority of naturally occurring discussions fall much nearer the continuum's bottom than its top. By and large, they involve little focus on seriously weighing the merits, and the participants have little knowledge to share (Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine Reference Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine2000; Kinder and Kalmoe Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017; Luskin Reference Luskin1987), are demographically similar and attitudinally like-minded (Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine Reference Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine2000; Butters and Hare Reference Butters and Hare2020; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001), circumnavigate whatever few areas of disagreement exist (Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine Reference Bennett, Flickinger and Rhine2000; Cowan and Baldassarri Reference Cowan and Baldassarri2018; Gerber et al. Reference Gerber2012), and discount whatever little counterattitudinal information may nevertheless poke through (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013). This is a far cry from ‘deliberation’ (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge, Elkin and Soltan1999a; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge and Macedo1999b).

It would therefore be a mistake to regard studies of naturally occurring discussions (as in, for example, Beck et al. Reference Beck2002; Huckfeldt and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995; Mutz Reference Mutz2006, or Searing et al. Reference Searing2007) as saying much about deliberation. For that, we need deliberative designs: discussions organized to be more much deliberative than the vast majority of those in everyday life. Examples include Consensus Conferences and Citizens' Juries (thumbnailed by Ozanne, Corus and Saatcioglu Reference Ozanne, Corus and Saatcioglu2009), as well as DPs. In varying ways, and with varying success, these all get their participants to talk more about policy issues, to learn and think more about them, and to do so in a more earnest, open-minded way.

Policy Attitudes

We take policy attitudes to be evaluations of policy options: how much one favors or opposes X or favors or opposes X over Y.Footnote 4 A policy attitude is thus ‘positional’ – expressible as a point on a numerical continuum (taken here to run from 0 to 1, with 0.5 representing neutrality). We denote the ith individual's time-t attitude on the jth issue by Aijt, where t = 1, 2 (pre- versus post-deliberation).

Policy-Attitude-Associated Cognition

Assorted cognitions (perceptions, beliefs, perspectives) may underpin Aijt. Collectively these may be more or less complex (numerous and cognitively interconnected), more or less factually accurate, and more or less balanced (congenial, in equal or representative proportions, to opposing sides). Note that these cognitive variables – call them Cijt, Fijt, and Bijt – are conceptually distinct from the attitudes they support. The time-t attitude is just Aijt, no matter the Cijt, Fijt or Bijt behind it. Individuals 1 and 2 may have the same attitude (A 1jt = A 2jt) even if, for example, C 1jt > C 2jt, making 1's attitude better ‘developed’ or ‘crystallized’ (further from what Converse (Reference Converse and Tufte1970) called a ‘non-attitude’). Similarly, the time-1 to time-2 attitude change is just Aij 2 − Aij 1, however much or little Cijt, Fijt, or Bijt may have changed.

Full-Consideration Attitudes

The attitudes people have are not necessarily those they would have with the benefit of unlimited information and reflection. Denote the ith individual's full-consideration attitude on the jth issue as ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $. Axiomatically, we take this to be the attitude most closely aligned with his or her values and interests.

$A_{ij}^\ast $. Axiomatically, we take this to be the attitude most closely aligned with his or her values and interests. ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $ is thus close kin to Lau and Redlawsk's (Reference Lau and Redlawsk1997) ‘correct votes’, Mansbridge's (Reference Mansbridge1983) ‘enlightened preferences’, and the ‘full-information’ votes and policy attitudes simulated by Bartels (Reference Bartels1996), Delli Carpini and Keeter (Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996), and Althaus (Reference Althaus2003), among many others. Now, we never know

$A_{ij}^\ast $ is thus close kin to Lau and Redlawsk's (Reference Lau and Redlawsk1997) ‘correct votes’, Mansbridge's (Reference Mansbridge1983) ‘enlightened preferences’, and the ‘full-information’ votes and policy attitudes simulated by Bartels (Reference Bartels1996), Delli Carpini and Keeter (Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996), and Althaus (Reference Althaus2003), among many others. Now, we never know ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $. Even estimating it can be tricky (Luskin Reference Luskin, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003). But here we need it only as a conceptual touchstone, for which we need only posit its existence.

$A_{ij}^\ast $. Even estimating it can be tricky (Luskin Reference Luskin, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003). But here we need it only as a conceptual touchstone, for which we need only posit its existence.

Appropriateness

In similar vein, we may define an attitude's appropriateness (for the individual holding it) as its proximity to its holder's full-consideration attitude: αijt ≡ 1 − ![]() $\vert {A_{ijt}-A_{ij}^\ast } \vert $. Thus αijt = 1 when A ijt =

$\vert {A_{ijt}-A_{ij}^\ast } \vert $. Thus αijt = 1 when A ijt = ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $ and = 0 when A ijt = 1 and

$A_{ij}^\ast $ and = 0 when A ijt = 1 and ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $ = 0, or vice versa.

$A_{ij}^\ast $ = 0, or vice versa.

Homogenization, Polarization, and Domination

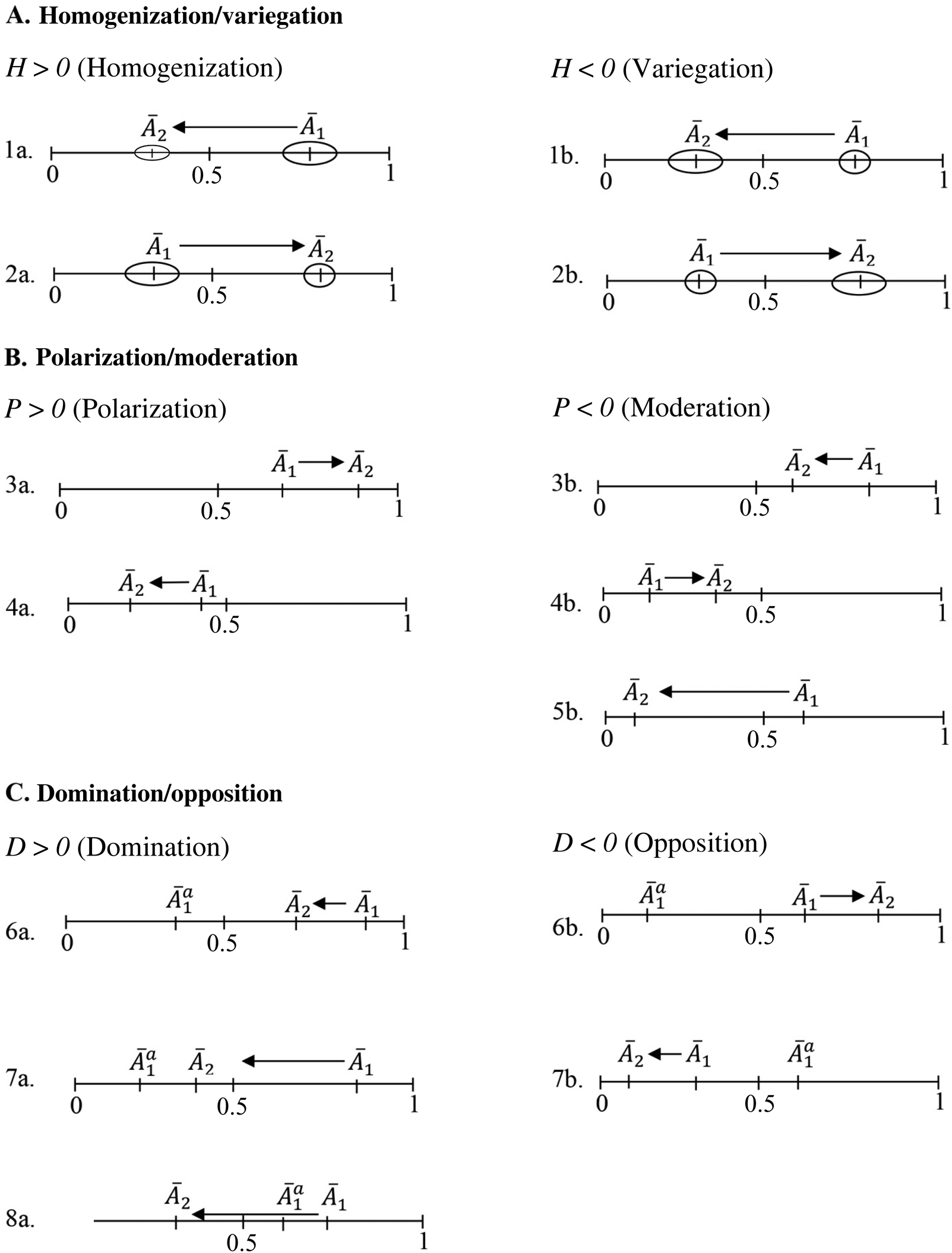

Our focal variables are all species of group-level attitude change. It sometimes makes sense to treat them as dichotomies, simply distinguishing cases in which they occur from those in which they do not. More informatively, however, they can be treated as continua centered at 0. Their names express their worried-about sides (taken to be numerically positive), but the opposite sides (taken to be numerically negative) also exist: a group's attitudes may exhibit homogenization or variegation (decreasing or increasing variance); polarization or moderation (movement toward or away from the nearer extreme), and domination or opposition (movement toward or away from the attitudes of the group's socially advantaged members).

To formalize these variables, let Aijt's time-t mean within the gth group be ![]() $\bar{A}_{gjt}$; its time-t standard deviation within the gth group be sgjt; and, assuming some mutually exclusive, exhaustive division into advantaged and disadvantaged, its time-t mean for the gth group's advantaged and disadvantaged members be

$\bar{A}_{gjt}$; its time-t standard deviation within the gth group be sgjt; and, assuming some mutually exclusive, exhaustive division into advantaged and disadvantaged, its time-t mean for the gth group's advantaged and disadvantaged members be ![]() $\bar{A}_{gjt}^a $ and

$\bar{A}_{gjt}^a $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gjt}^d $. In these terms:

$\bar{A}_{gjt}^d $. In these terms:

The homogenization of the gth group's attitudes on the jth issue is:Footnote 5

which > 0 for homogenization, < 0 for variegation, and = 0 for neither. Figure 1 illustrates, representing the within-group variation by more or less elongated ellipses. Regardless of what happens to the mean (compare Panels A1a and A2a with Panels A1b and A2b), a decreasing variance (as in Panels A1a and A2a) is homogenization, an increasing one (as in Panels A1b and A2b) variegation. Hgj is at its most positive (0.5) when the participants are evenly split between the polar attitudes (half at 0, half at 1) before deliberating but all have exactly the same attitude (whatever it may be) after doing so – changing, that is, from perfect dissensus (sgj 1 = 0.5) to perfect consensus (sgj 2 = 0). It is at its most negative (–0.5) for the opposite change, from perfect consensus to perfect dissensus. The binary version is ![]() $H_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Hgj > 0 and = 0 if Hgj ⩽ 0. Redundantly, though perhaps usefully for later exposition, the complementary binary variable for variegation can be defined as

$H_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Hgj > 0 and = 0 if Hgj ⩽ 0. Redundantly, though perhaps usefully for later exposition, the complementary binary variable for variegation can be defined as ![]() $V_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Hgj < 0 and = 0 if Hgj ⩾ 0.Footnote 6

$V_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Hgj < 0 and = 0 if Hgj ⩾ 0.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Illustrating the definitions.

The polarization of the gth group's attitudes on the jth issue is:

where Sgj 1 indicates the gth group's time-1 side on the jth issue: Sgj 1 = 1 for ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5 and = –1 for

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5 and = –1 for ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < 0.5. The multiplication by Sgj 1 ensures that Pgj > 0 for polarization, < 0 for moderation, and = 0 for neither (no mean attitude change).Footnote 7 Panels B3a and B4a show

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < 0.5. The multiplication by Sgj 1 ensures that Pgj > 0 for polarization, < 0 for moderation, and = 0 for neither (no mean attitude change).Footnote 7 Panels B3a and B4a show ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ moving toward the nearer extreme (polarization); Panels B3b, B4b, and B5b show it moving in the opposite direction, toward or beyond the midpoint (moderation).Footnote 8 Pgj is at its most positive (just barely under 0.5) when the mean is either just barely above 0.5 before deliberation and exactly 1 after or just barely below 0.5 before deliberation and exactly 0 after. It is at its most negative (just barely above −1) when the mean is just fractionally toward the midpoint from the nearer pole (just barely below 1 or above 0) before deliberating and at the opposite pole (0 or 1) after.Footnote 9 The binary version is

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ moving toward the nearer extreme (polarization); Panels B3b, B4b, and B5b show it moving in the opposite direction, toward or beyond the midpoint (moderation).Footnote 8 Pgj is at its most positive (just barely under 0.5) when the mean is either just barely above 0.5 before deliberation and exactly 1 after or just barely below 0.5 before deliberation and exactly 0 after. It is at its most negative (just barely above −1) when the mean is just fractionally toward the midpoint from the nearer pole (just barely below 1 or above 0) before deliberating and at the opposite pole (0 or 1) after.Footnote 9 The binary version is ![]() $P_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Pgj > 0 and = 0 if Pgj ⩽ 0. Its complement, for moderation, is

$P_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Pgj > 0 and = 0 if Pgj ⩽ 0. Its complement, for moderation, is ![]() $M_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Pgj < 0 and = 0 if Pgj ⩾ 0.

$M_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Pgj < 0 and = 0 if Pgj ⩾ 0.

The domination of the gth group's attitudes on the jth issue (with respect to a given dimension of advantage) is:

where R gj1 indicates the ordinal relation between ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $: R gj1 = 1 for

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $: R gj1 = 1 for ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a > \bar{A}_{gj1}$ and = –1 for

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a > \bar{A}_{gj1}$ and = –1 for ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a < \bar{A}_{gj1}$. Thus Dgj > 0 for domination, < 0 for opposition and = 0 for neither (no mean attitude change).Footnote 10 In Figure 1, C6a, C7a, and C8a show

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a < \bar{A}_{gj1}$. Thus Dgj > 0 for domination, < 0 for opposition and = 0 for neither (no mean attitude change).Footnote 10 In Figure 1, C6a, C7a, and C8a show ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ moving toward or beyond

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ moving toward or beyond ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (domination), while C6b and C7b show it moving in the opposite direction, away from

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (domination), while C6b and C7b show it moving in the opposite direction, away from ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (opposition). Dgj is at its most positive (just barely < 1) when the disadvantaged start at 1 or 0, the advantaged start just barely toward the midpoint from that (as, therefore, does the whole group), and everyone, whether advantaged or disadvantaged, moves all the way to the opposite pole (0 or 1), not only toward but as far as possible beyond

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (opposition). Dgj is at its most positive (just barely < 1) when the disadvantaged start at 1 or 0, the advantaged start just barely toward the midpoint from that (as, therefore, does the whole group), and everyone, whether advantaged or disadvantaged, moves all the way to the opposite pole (0 or 1), not only toward but as far as possible beyond ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $. It is at its most negative (just barely > −1) when the advantaged start at 1 or 0, the disadvantaged start just barely toward the midpoint from that, as therefore does the whole group), and everyone moves all the way to the opposite pole (0 or 1), as far as possible away from

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $. It is at its most negative (just barely > −1) when the advantaged start at 1 or 0, the disadvantaged start just barely toward the midpoint from that, as therefore does the whole group), and everyone moves all the way to the opposite pole (0 or 1), as far as possible away from ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $.Footnote 11 The binary version is

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $.Footnote 11 The binary version is ![]() $D_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Dgj > 0 and = 0 if Dgj ⩽ 0. Its complement, for opposition, is

$D_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Dgj > 0 and = 0 if Dgj ⩽ 0. Its complement, for opposition, is ![]() $O_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Dgj < 0 and = 0 if Dgj ⩾ 0.Footnote 12

$O_{gj}^b $ = 1 if Dgj < 0 and = 0 if Dgj ⩾ 0.Footnote 12

We shall examine three dimensions of advantage – gender, education, and income – both individually and all three combined.Footnote 13 For gender, a matter simply of sociodemographic group membership, the threshold of advantage (maleness) is relatively clear. For education and income, matters of having more or less of a numerical or ordinal property, it is less clear. But division at each DP's sample median makes sense for several reasons. First, the sample median varies from sample to sample, tacitly recognizing that what is highly educated or high income varies by time and place. Social advantage is relative. Second, the sample median, unlike the small-group median, lets the proportions of advantaged versus disadvantaged vary from group to group. Third, the median, compared to other sample-dependent cut-points, minimizes the proportion of small groups for which the number of either disadvantaged or advantaged members scrapes zero. Fourth, the median is a good guess when we do not know where to draw the line. If the actual proportion of the sample that is disadvantaged has a symmetric (Bayesian) probability distribution centered at 0.5 (the uniform distribution being a special case), the minimum mean-squared-error guess is 0.5, corresponding to division at the median.

Theory, Expectations and Inferences

In broad strokes, our central proposition is that homogenization, polarization and domination rest (and therefore shed light) on the deliberative quality of the discussion. It will help in developing the why's and how's to note that the population means of Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj (averaging across all possible group-issue pairs, a sense of ‘population’ about which we say a bit more below) are E(Hgj), E(Pgj), and E(Dgj), where E(.) denotes mathematical expectation. Positive values indicate the extent to which, on average, homogenization exceeds variegation, polarization exceeds moderation, and domination exceeds opposition; negative values, the reverse. Similarly, the relative frequencies of homogenization, polarization, and domination are E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $), E(

$H_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $), and E(

$P_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $), and those of variegation, moderation, and opposition E(

$D_{gj}^b $), and those of variegation, moderation, and opposition E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(

$V_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $), E(

$H_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(

$M_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $), and E(

$P_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(

$O_{gj}^b $) = 1 − E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $). It will also help, at points, to take

$D_{gj}^b $). It will also help, at points, to take ![]() $\vert {{\bar{A}}_{gjt}-\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ and

$\vert {{\bar{A}}_{gjt}-\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ and ![]() $\vert {s_{gjt}-s_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ – the distances between a group's sample-mean attitude (

$\vert {s_{gjt}-s_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ – the distances between a group's sample-mean attitude (![]() $\bar{A}_{gjt}$) and its sample-mean full-consideration attitude (

$\bar{A}_{gjt}$) and its sample-mean full-consideration attitude (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $) and between the sample standard deviations of its members' jth-issue attitudes (sgjt) and of their full-consideration attitudes (

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $) and between the sample standard deviations of its members' jth-issue attitudes (sgjt) and of their full-consideration attitudes (![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $) – as simple, tractable reflections of group-level ‘appropriateness’. The smaller these distances, the more appropriate the group's attitudes.

$s_{gj}^\ast $) – as simple, tractable reflections of group-level ‘appropriateness’. The smaller these distances, the more appropriate the group's attitudes.

Social Dynamics versus Weighing the Merits

We see two broad mechanisms by which a discussion may change policy attitudes.

Social dynamics (SD)

The first lies in the discussion's social interactions, the relevant features of which we shall call its social dynamics (SD). People commonly seek approval and sidestep disagreement. That should shrink the initial within-group standard deviation sgj 1 (Cialdini and Goldstein Reference Cialdini and Goldstein2004; Gerber et al. Reference Gerber2012; Huckfeldt and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995; Huckfeldt, Johnson and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt, Johnson and Sprague2004; Mutz Reference Mutz2006; Suhay Reference Suhay2015; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2002; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2009; Sunstein and Hastie Reference Sunstein and Hastie2014) and pull the initial group mean attitude ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ toward the nearer extreme (Suhay Reference Suhay2015; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2002; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2009; Sunstein and Hastie Reference Sunstein and Hastie2014; Wojcieszak Reference Wojcieszak2011; Zuber, Crott and Werner Reference Zuber, Crott and Werner1992). In addition, some participants, often concentrated among the socially disadvantaged, will normally be less articulate, less assertive, or less heeded than others. That should move

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ toward the nearer extreme (Suhay Reference Suhay2015; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2002; Sunstein Reference Sunstein2009; Sunstein and Hastie Reference Sunstein and Hastie2014; Wojcieszak Reference Wojcieszak2011; Zuber, Crott and Werner Reference Zuber, Crott and Werner1992). In addition, some participants, often concentrated among the socially disadvantaged, will normally be less articulate, less assertive, or less heeded than others. That should move ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ toward

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ toward ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (Fraser Reference Fraser and Robbin1993; Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012; Sanders Reference Sanders1997; Young Reference Young2000). Hence SD should produce homogenization, polarization, and domination – not always strongly, nor in every instance, but on average and more often than not. More formally, we should expect E(Hgj), E(Pgj), E(Dgj) all ≫ 0, and E(

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ (Fraser Reference Fraser and Robbin1993; Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012; Sanders Reference Sanders1997; Young Reference Young2000). Hence SD should produce homogenization, polarization, and domination – not always strongly, nor in every instance, but on average and more often than not. More formally, we should expect E(Hgj), E(Pgj), E(Dgj) all ≫ 0, and E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $), E(

$H_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $), and E(

$P_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $) all ≫ 0.5 and, ipso facto, ≫ E(

$D_{gj}^b $) all ≫ 0.5 and, ipso facto, ≫ E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $), E(

$V_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $), and E(

$M_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $).

$O_{gj}^b $).

Weighing the merits (WM)

The second mechanism is the participants' open-minded, even-handed, and earnest weighing of the merits (the arguments and evidence), as they see them – the deliberation in the discussion, call it WM. This where Habermas's (Reference Habermas, Benhabib and Dallmayer1990, Reference Habermas1996) ‘unforced force of the better argument’ resides. In WM, participants can be expected to absorb nontrivial quantities of new information, higher-than-everyday proportions of which are accurate and counterattitudinal, thus increasing Cij 1, Fij 1, and Bij 1 (as the results in Barabas Reference Barabas2004; Hansen Reference Hansen2004; Luskin, Fishkin, and Jowell Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002; and Farrar et al. Reference Farrar2010 suggest). That, in turn, should allow them to see more clearly how given policies may serve or thwart their values and interests (which they may also come to see more clearly), thus moving A ijt closer to ![]() $A_{ij}^\ast $Footnote 14 and, at the group level, reducing the distances

$A_{ij}^\ast $Footnote 14 and, at the group level, reducing the distances ![]() $\vert {{\bar{A}}_{gjt}-\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ and

$\vert {{\bar{A}}_{gjt}-\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast } \vert $ and ![]() $\vert {s_{gjt}-s_{gj}^\ast } \vert $. There is no obvious reason to expect these changes to constitute homogenization, polarization, or domination (or their opposites), although …

$\vert {s_{gjt}-s_{gj}^\ast } \vert $. There is no obvious reason to expect these changes to constitute homogenization, polarization, or domination (or their opposites), although …

A Closer Look at WM's Effects

We can actually reason out some rough expectations about WM-induced homogenization/variegation, polarization/moderation, and domination/opposition by taking account of the pre-existing homogenization/variegation, polarization/moderation, and domination/opposition (call them ![]() $H_{gj}^o $,

$H_{gj}^o $, ![]() $P_{gj}^o $, and

$P_{gj}^o $, and ![]() $D_{gj}^o $) of the outside-world attitudes with which the discussion begins. These latter can most sensibly be defined as differences between the initial sgj 1 and

$D_{gj}^o $) of the outside-world attitudes with which the discussion begins. These latter can most sensibly be defined as differences between the initial sgj 1 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and the full-consideration

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and the full-consideration ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $ and

$s_{gj}^\ast $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ (in contrast to Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj, which are differences between the initial sgj 1 and

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ (in contrast to Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj, which are differences between the initial sgj 1 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and the post-discussion sgj 2 and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ and the post-discussion sgj 2 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj2}$).Footnote 15

$\bar{A}_{gj2}$).Footnote 15

Figure 2 illustrates the pre-existing ![]() $H_{gj}^o $,

$H_{gj}^o $, ![]() $P_{gj}^o $, and

$P_{gj}^o $, and ![]() $D_{gj}^o $ alongside the corresponding WM-induced Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj. To avoid redundant mirror-image cases, we assume, without loss of generality, that

$D_{gj}^o $ alongside the corresponding WM-induced Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj. To avoid redundant mirror-image cases, we assume, without loss of generality, that ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5, making 1 the nearer extreme. The lower, solid arrows depict the WM-induced attitude changes, moving sgjt and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5, making 1 the nearer extreme. The lower, solid arrows depict the WM-induced attitude changes, moving sgjt and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gjt}$ toward

$\bar{A}_{gjt}$ toward ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $ and

$s_{gj}^\ast $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $, and the upper, dashed ones the prior effects of outside-world forces, pulling the initial s gj1 and

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $, and the upper, dashed ones the prior effects of outside-world forces, pulling the initial s gj1 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ above the full-consideration

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ above the full-consideration ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $ and

$s_{gj}^\ast $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ in Scenario A and below them in Scenario B. Scenario A consists of pre-existing variegation (sgj 1 >

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ in Scenario A and below them in Scenario B. Scenario A consists of pre-existing variegation (sgj 1 > ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $), polarization (

$s_{gj}^\ast $), polarization (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$), and domination (

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$), and domination (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ or

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ or ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$, given

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$, given ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$), Scenario B of pre-existing homogenization (sgj 1 <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$), Scenario B of pre-existing homogenization (sgj 1 < ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $), moderation (

$s_{gj}^\ast $), moderation (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $), and opposition (

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $), and opposition (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $, given

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $, given ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $).Footnote 16 We shall return to the two possibilities for pre-existing domination in Figure 2's rows 3a and 3b.

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $).Footnote 16 We shall return to the two possibilities for pre-existing domination in Figure 2's rows 3a and 3b.

Figure 2. Homogenization. Polarization, and Domination to Be Expected in the Outside World, then from Weighing the Merits.

Note: A 1, A 2, A*, A 1a, s 1, s 2, and s* are short for the text's Ā gj1, Ā gj2, Ā gj*, sgj 1, sgj 2, and S gj*. We assume, without loss of generality, that Ā gj1 > 0.5.

Scenarios A and B are alternative legacies of the forces shaping outside-world attitudes. Some of those forces – notably, communications siloing (residential and other sorting, homophily, selective media consumption) and social inequalities – are centrifugal, pulling the initial attitudes away from 0.5, toward both the nearer extreme and the mean attitude of the advantaged (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), and thus also (since the nearer extreme is 0 for some group members but 1 for others) increasing their variance. Other forces – principally, inattention, ignorance, and irreflection – are centripetal, keeping the initial attitudes closer to 0.5 and thus also restraining their variance. The centrifugal forces make for Scenario A, the centripetal ones for Scenario B.Footnote 17 The world, of course, involves a mix of both kinds of forces. The centrifugal ones are presently much noted (and understandably bemoaned). But, behind the scenes, the centripetal ones are at the same time etiolating the attitudes of the less politically engaged – and, on low-salience issues, many of those of the more politically engaged as well.

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), and thus also (since the nearer extreme is 0 for some group members but 1 for others) increasing their variance. Other forces – principally, inattention, ignorance, and irreflection – are centripetal, keeping the initial attitudes closer to 0.5 and thus also restraining their variance. The centrifugal forces make for Scenario A, the centripetal ones for Scenario B.Footnote 17 The world, of course, involves a mix of both kinds of forces. The centrifugal ones are presently much noted (and understandably bemoaned). But, behind the scenes, the centripetal ones are at the same time etiolating the attitudes of the less politically engaged – and, on low-salience issues, many of those of the more politically engaged as well.

What Figure 2 makes clear is that WM can be expected to ‘correct’ what the outside world has done – producing homogenization, moderation, and opposition that reduce or reverse the pre-existing variegation, polarization, and domination in Scenario A and variegation, polarization, and domination that reduce or reverse the pre-existing homogenization, moderation, and opposition in Scenario B. As drawn, the arrows (shorter from sgj 1 to sgj 2 and from ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ to

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ to ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj2}$ than from

$\bar{A}_{gj2}$ than from ![]() $s_{gj}^\ast $ to sgj 1 and from

$s_{gj}^\ast $ to sgj 1 and from ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ to

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ to ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$) depict reductions, which seem likelier than reversals (its being hard for a few days of discussion to completely negate the accumulated effects of a lifetime of prior circumstances and experiences). The reduction or reversal may be slightly smaller for Scenario A's pre-existing domination, which can yield WM-induced opposition in 3a but WM-induced domination in 3b, than for Scenario A's pre-existing variegation or polarization (or anything in Scenario B). But the centrifugal forces pulling

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$) depict reductions, which seem likelier than reversals (its being hard for a few days of discussion to completely negate the accumulated effects of a lifetime of prior circumstances and experiences). The reduction or reversal may be slightly smaller for Scenario A's pre-existing domination, which can yield WM-induced opposition in 3a but WM-induced domination in 3b, than for Scenario A's pre-existing variegation or polarization (or anything in Scenario B). But the centrifugal forces pulling ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ above

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ above ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ should also pull the better-educated and better-off, who tend to be more exposed to the information and messaging involved, still further above it (

$\bar{A}_{gj}^\ast $ should also pull the better-educated and better-off, who tend to be more exposed to the information and messaging involved, still further above it (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), making 3a much more common than 3b.

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), making 3a much more common than 3b.

The lesson for the frequencies of WM-induced homogenization/variegation, polarization/moderation, and domination/opposition is that they ultimately depend on the balance between centrifugal and centripetal forces. Absent much reason to see either as greatly stronger than the other, the safest guess, and our expectation, is that they are about equally strong. In this case, WM should produce homogenization, polarization, and domination about half the time and variegation, moderation, and opposition about half the time: E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(

$H_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(

$V_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(

$P_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(

$M_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(

$D_{gj}^b $) ≅ E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $) ≅ 0.5. To the extent that these proportions depart from 0.5, however, we might expect to see slightly more homogenization than variegation but slightly less polarization and domination than moderation and opposition. These are increasingly tribal days (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016), in which the balance of outside-world forces may be tipping toward the centrifugal. Probably not too grossly, to be sure. Inattention, ignorance, and irreflection remain forever widespread and potent, and should keep E(

$O_{gj}^b $) ≅ 0.5. To the extent that these proportions depart from 0.5, however, we might expect to see slightly more homogenization than variegation but slightly less polarization and domination than moderation and opposition. These are increasingly tribal days (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016), in which the balance of outside-world forces may be tipping toward the centrifugal. Probably not too grossly, to be sure. Inattention, ignorance, and irreflection remain forever widespread and potent, and should keep E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $), E(

$H_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $), and E(

$P_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $) (and E(

$D_{gj}^b $) (and E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $), E(

$V_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $), and E(

$M_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $)) from departing too much from 0.5.

$O_{gj}^b $)) from departing too much from 0.5.

Theoretical Asides

Two side notes, important in different ways to our post-analysis reflections below, need sounding.

Motivated reasoning

The first is that both WM and SD entail varieties of ‘motivated reasoning’, a term often simplistically reduced to ways of ignoring, discounting, or reasoning around counterattitudinal information. This too-narrow sense is apt enough when the motivations are strictly or mainly ‘defensive’. In that case, discussion should tend to produce little attitude change. But defensive motivations may be less pervasive than previously thought (Arceneaux and Vander Wielen Reference Arceneaux and Vander Wielen2017; Druckman Reference Druckman2012; Druckman and McGrath Reference Druckman and McGrath2019; Hahn and Harris Reference Hahn and Harris2014; Hart et al. Reference Hart2009; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Már and Gastil Reference Már and Gastil2020), and are hardly the only motivations in play (Kunda Reference Kunda1990), not even the only ‘directional’ ones (Hart et al. Reference Hart2009). In discussions, social approval motivations (to please or favorably impress others) are important to SD, and accuracy motivations (to ‘process information in an objective, open-minded fashion …’, Hart et al. Reference Hart2009, 558) important to WM. Both can be expected to change attitudes – the former in directions tending to yield homogenization, polarization, and domination, the latter in the direction of full-consideration attitudes.

Contextual factors

The second note concerns the conditions under which the discussion occurs. A discussion involving a serious weighing of the merits is deliberative, but the deliberation may be more or less ‘effective’ – more or less helpful to its participants in considering what their attitudes should be – depending on who is ‘in the room’ and (not unrelatedly) the information readily available to them. The more demographically and attitudinally heterogeneous the discussants, and the more plentiful, balanced, and accurate the information, the harder it is for the discussion and its participants to misconstrue, slight, or ignore relevant information and arguments (see Mercier and Landemore Reference Mercier and Landemore2012; Tuller et al. Reference Tuller2015). These variables, too, are part of what separates successful deliberative designs from everyday discussions, in which homophily and sorting make the discussants relatively homogeneous, and the information is generally confined to whatever the discussants bring with them, which is, for most of them, in most discussions, sparse, imbalanced and/or inaccurate.Footnote 18

In Sum

A discussion's effects on homogenization, polarization, and domination should depend on how deliberative it is – on how much it revolves around WM. Everyday discussions, involving much SD and little WM, can be expected to yield decidedly more homogenization than variegation, polarization than moderation, and domination than opposition. The deliberative discussions spawned by successful deliberative designs should not. If anything, they may produce some slight homogenization, but also, if so, some slight moderation and opposition.

These widely different expectations allow the observed distributions of Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj and ![]() $H_{gj}^b $,

$H_{gj}^b $, ![]() $P_{gj}^b $, and

$P_{gj}^b $, and ![]() $D_{gj}^b $ to form a rough diagnostic. If the sample means

$D_{gj}^b $ to form a rough diagnostic. If the sample means ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$,

$\bar{P}$, ![]() $\bar{D}$ (estimating E(Hgj), E(Pgj), and E(Dgj)) are well above 0, or the sample frequencies

$\bar{D}$ (estimating E(Hgj), E(Pgj), and E(Dgj)) are well above 0, or the sample frequencies ![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ (estimating E(

$\bar{D}^b$ (estimating E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $), E(

$H_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $), and E(

$P_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $)) well above 0.5, the discussion is probably not very deliberative, involving little beyond SD. If instead

$D_{gj}^b $)) well above 0.5, the discussion is probably not very deliberative, involving little beyond SD. If instead ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ are all close to 0, and

$\bar{D}$ are all close to 0, and ![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ all close to 0.5, the discussion is probably quite deliberative, involving a healthy dose of WM.

$\bar{D}^b$ all close to 0.5, the discussion is probably quite deliberative, involving a healthy dose of WM.

Data

We take our data from Deliberative Polling, a well-known deliberative design (described, for example, in Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002). Its signal features include randomly sampled participants, randomly assigned to small groups; honoraria to help recruit hard-to-get participants, including those unenticed by the prospect of discussing the policy issue; balanced, factually accurate briefing materials provided in advance; lightly moderated small-group discussions alternating with plenary question-and-answer sessions with panels of policy experts; and anonymous questionnaires to gauge policy attitudes and other relevant variables both before and after deliberation. The twenty-one DPs supplying our data are summarized in Table 1. Five were in Britain, eleven in the United States, two in the EU, and one each in China, Australia, and Bulgaria. Sixteen were face to face, five online. The topics spanned policy issues from foreign policy to health care. In all, the data encompass 372 small groups (containing, all told, 5,736 participants), 139 policy issues (counting each policy attitude index as tapping an at least somewhat different issue), and 2,601 group-issue pairs.Footnote 19 Appendix A describes the indices and their ingredients in greater detail.

Table 1. DPs analyzed

Note: WTU, West Texas Utilities; CP&L, Central Power & Light; SEP, Southwestern Electric Power.

a All (then twenty-seven) Member-States.

In the fullest accounting, we are sampling time-indexed person-populations (for example, Great Britain in 1994, which is in our sample, or Paraguay in 2011, which is not), then both the individuals within those time-indexed person-populations and the policy issues facing them (for example, crime in Bulgaria in 2007, which is in our sample, and climate change in the United States in 2009, which is not). The samples of individuals are almost always random draws. The samples of time-indexed person-populations and policy issues are not. Yet we hope they are large and varied enough to afford some hard-to-quantify but nonzero sense that the results are unlikely to be peculiar to just a few places, times, or issues. Although most of the DPs here were in Anglo-American democracies and conducted face-to-face, ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ are only trivially different for the group-issue pairs from other countries and in online mode, as can be seen in Appendix B.

$\bar{D}$ are only trivially different for the group-issue pairs from other countries and in online mode, as can be seen in Appendix B.

Results

So how much homogenization, polarization, and domination does there appear to be? The short answer is, very little. Figure 3 shows the distributions of the group-issue-level Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj across group-issue pairs. All are packed tightly and symmetrically around near-zero means. Some group-issue pairs exhibit homogenization, some variegation; some exhibit polarization, some moderation; some exhibit domination, some opposition. But often and on average very little of any.

Figure 3. Distributions of group-issue pairs on H gj, P gj and D gj.

Table 2 homes in on the means (![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$,

$\bar{P}$, ![]() $\bar{D}$) and relative frequencies (

$\bar{D}$) and relative frequencies (![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$). The top row shows

$\bar{D}^b$). The top row shows ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$,

$\bar{P}$, ![]() $\bar{D}$,

$\bar{D}$, ![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$, the lower rows the Huber-White estimates of the standard errors (White Reference White1980),Footnote 20 and two-tailed p-values for the null hypotheses that E(Hgj) = E(Pgj) = E(Dgj) = 0 and E(

$\bar{D}^b$, the lower rows the Huber-White estimates of the standard errors (White Reference White1980),Footnote 20 and two-tailed p-values for the null hypotheses that E(Hgj) = E(Pgj) = E(Dgj) = 0 and E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $) = E(

$H_{gj}^b $) = E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $) = E(

$V_{gj}^b $) = E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $) = E(

$P_{gj}^b $) = E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $) = E(

$M_{gj}^b $) = E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $) = E(

$D_{gj}^b $) = E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $) = 0.5 – that in the population of all possible group-issue pairs the mean levels of homogenization, polarization, and domination are 0 and that each occurs only as often as its opposite (as would be expected from WM, assuming centrifugal and centripetal forces to be equally strong).Footnote 21 The alternative hypotheses are that E(Hgj), E(Pgj), E(Dgj) all > 0 and that E(

$O_{gj}^b $) = 0.5 – that in the population of all possible group-issue pairs the mean levels of homogenization, polarization, and domination are 0 and that each occurs only as often as its opposite (as would be expected from WM, assuming centrifugal and centripetal forces to be equally strong).Footnote 21 The alternative hypotheses are that E(Hgj), E(Pgj), E(Dgj) all > 0 and that E(![]() $H_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(

$H_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(![]() $V_{gj}^b $), E(

$V_{gj}^b $), E(![]() $P_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(

$P_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(![]() $M_{gj}^b $), and E(

$M_{gj}^b $), and E(![]() $D_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(

$D_{gj}^b $) > 0.5 > E(![]() $O_{gj}^b $) – that the mean levels of homogenization, polarization, and domination are all positive and that each occurs more often than its opposite.

$O_{gj}^b $) – that the mean levels of homogenization, polarization, and domination are all positive and that each occurs more often than its opposite.

Table 2. Homogenization, polarization and domination: occurrence and (signed) magnitude

Note: in the ‘Mean’ row, the entries for Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj are the means of those variables (![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$). Those for

$\bar{D}$). Those for ![]() $H_{gj}^b $,

$H_{gj}^b $, ![]() $P_{gj}^b $, and

$P_{gj}^b $, and ![]() $D_{gj}^b $ (

$D_{gj}^b $ (![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$) are the relative frequencies with which Hgj > 0, Pgj > 0, and Dgj > 0.

$\bar{D}^b$) are the relative frequencies with which Hgj > 0, Pgj > 0, and Dgj > 0.

In their stronger versions (![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ ≫ 0 and

$\bar{D}$ ≫ 0 and ![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ ≫ 0.5), these alternatives are what would be expected from a discussion involving mostly SD. But Table 2 shows nothing of the sort. True, six of the table's ten estimates are statistically significant (p < 0.05). In these cases, we can be quite sure that, in the population from which we are sampling, there is some homogenization or variegation (depending on the signs of

$\bar{D}^b$ ≫ 0.5), these alternatives are what would be expected from a discussion involving mostly SD. But Table 2 shows nothing of the sort. True, six of the table's ten estimates are statistically significant (p < 0.05). In these cases, we can be quite sure that, in the population from which we are sampling, there is some homogenization or variegation (depending on the signs of ![]() $\bar{H}$ and

$\bar{H}$ and ![]() $\bar{H}^b$ – 0.5), some polarization or moderation (depending on the signs of

$\bar{H}^b$ – 0.5), some polarization or moderation (depending on the signs of ![]() $\bar{P}$ and

$\bar{P}$ and ![]() $\bar{P}^b$ − 0.5), and some domination or opposition (depending on the signs of

$\bar{P}^b$ − 0.5), and some domination or opposition (depending on the signs of ![]() $\bar{D}$ and

$\bar{D}$ and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ − 0.5). But how much? At a glance,

$\bar{D}^b$ − 0.5). But how much? At a glance, ![]() $\bar{H}^b$,

$\bar{H}^b$, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$, and

$\bar{P}^b$, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ are close to 0.5,

$\bar{D}^b$ are close to 0.5, ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ close to 0.

$\bar{D}$ close to 0.

A closer look reinforces that impression. Take homogenization. ![]() $\bar{H}^b$ = 0.595, distinctly above but still quite close to 0.5 (less than 20 percent of the way to 1). This is far from ‘routine’. On average, moreover, it is weak. To see this, imagine a group of twenty participants whose initial attitudes are as follows: four at 0.6 and two each at every other integer multiple of 0.1 from 0.2 to 1. This initial distribution has a mean of 0.6 and a middling standard deviation of 0.245, close to halfway between sgjt's maximum of 0.5 and minimum of 0. Now let one of the participants initially at 0.2 move to 0.3 and one of those initially at 1 move to 0.9 – in each case, 0.1 closer to the mean. This is not much homogenization: the distribution is almost completely unaltered. The mean remains 0.6, while the standard deviation shrinks from 0.245 to 0.230. This unimposing scenario thus yields Hgj = 0.015. The observed

$\bar{H}^b$ = 0.595, distinctly above but still quite close to 0.5 (less than 20 percent of the way to 1). This is far from ‘routine’. On average, moreover, it is weak. To see this, imagine a group of twenty participants whose initial attitudes are as follows: four at 0.6 and two each at every other integer multiple of 0.1 from 0.2 to 1. This initial distribution has a mean of 0.6 and a middling standard deviation of 0.245, close to halfway between sgjt's maximum of 0.5 and minimum of 0. Now let one of the participants initially at 0.2 move to 0.3 and one of those initially at 1 move to 0.9 – in each case, 0.1 closer to the mean. This is not much homogenization: the distribution is almost completely unaltered. The mean remains 0.6, while the standard deviation shrinks from 0.245 to 0.230. This unimposing scenario thus yields Hgj = 0.015. The observed ![]() $\bar{H}$ = 0.013 is still lower.

$\bar{H}$ = 0.013 is still lower.

Next take polarization. ![]() $\bar{P}^b$ = only 0.454, meaning that slightly fewer than half the group-issue pairs polarize (more than half moderate), and

$\bar{P}^b$ = only 0.454, meaning that slightly fewer than half the group-issue pairs polarize (more than half moderate), and ![]() $\bar{P}$ = –0.022, meaning that, on average, their mean attitudes move slightly toward, not away from, the midpoint, likewise representing moderation. To contextualize this

$\bar{P}$ = –0.022, meaning that, on average, their mean attitudes move slightly toward, not away from, the midpoint, likewise representing moderation. To contextualize this ![]() $\bar{P}$, take again a group of twenty with an initial mean attitude

$\bar{P}$, take again a group of twenty with an initial mean attitude ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ of 0.6. If just five of twenty members decrease their scores, from whatever starting points, by just 0.1 apiece (a scenario involving a bit more attitude change than the one sketched just above, but still not much),

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ of 0.6. If just five of twenty members decrease their scores, from whatever starting points, by just 0.1 apiece (a scenario involving a bit more attitude change than the one sketched just above, but still not much), ![]() $\bar{P}$ is only –0.025. The observed

$\bar{P}$ is only –0.025. The observed ![]() $\bar{P}$ is still smaller (–0.022).

$\bar{P}$ is still smaller (–0.022).

Finally, domination. Across our four dimensions of advantage, ![]() $\bar{D}^b$ runs only from 0.447 to 0.485. No matter what the dimension, fewer than 50 percent of the group-issue pairs move toward the initial mean attitude of the advantaged, meaning that more than 50 percent move away from it. This is (weak) opposition, not domination. The

$\bar{D}^b$ runs only from 0.447 to 0.485. No matter what the dimension, fewer than 50 percent of the group-issue pairs move toward the initial mean attitude of the advantaged, meaning that more than 50 percent move away from it. This is (weak) opposition, not domination. The ![]() $\bar{D}$'s tell much the same tale:

$\bar{D}$'s tell much the same tale: ![]() $\bar{D}$ = 0.008 for gender, = –0.013 for education, <0.0005 for income, and = –0.015 for threefold advantage. Again take a group of twenty members. Let

$\bar{D}$ = 0.008 for gender, = –0.013 for education, <0.0005 for income, and = –0.015 for threefold advantage. Again take a group of twenty members. Let ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ = 0.6 and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ = 0.6 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ = 0.8. If just three of the twenty participants decrease their scores by just 0.1 apiece, Dgj = –0.015. If just two do so, Dgj = –0.10. These scenarios involve scant attitude change, but their Dgj's bracket the negative

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ = 0.8. If just three of the twenty participants decrease their scores by just 0.1 apiece, Dgj = –0.015. If just two do so, Dgj = –0.10. These scenarios involve scant attitude change, but their Dgj's bracket the negative ![]() $\bar{D}$'s for education and threefold advantage. The positive

$\bar{D}$'s for education and threefold advantage. The positive ![]() $\bar{D}$'s for gender and income are still smaller. There is more opposition than domination, but not much of either.

$\bar{D}$'s for gender and income are still smaller. There is more opposition than domination, but not much of either.

The principal lesson is clear. The homogenization, polarization, and domination here are much too modest to suggest attitude changes stemming largely from SD but are consistent with attitude changes stemming largely from WM. A further suggestion, too faint and uncertain to be a ‘lesson’, lies in the signs of ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ and of

$\bar{D}$ and of ![]() $\bar{H}^b$'s,

$\bar{H}^b$'s, ![]() $\bar{P}^b$'s, and

$\bar{P}^b$'s, and ![]() $\bar{D}^b$'s departures from 0.5. These show some slight homogenization, moderation, and opposition, a combination suggesting that the deliberation may be redressing outside-world variegation, polarization, and domination.

$\bar{D}^b$'s departures from 0.5. These show some slight homogenization, moderation, and opposition, a combination suggesting that the deliberation may be redressing outside-world variegation, polarization, and domination.

Elaborations and Reflections

By way of follow-up, it may help to say a bit more about what ‘domination’, the most polyglot of our terms, does and does not mean; to elaborate on and probe our findings regarding it; to consider motivated reasoning's implications for our rough diagnostic; and to suggest some of the likeliest reasons for which our results diverge from some other studies’.

Dgj and the Meaning of Domination

‘Domination’, here, is simply attitude change – specifically, the group's mean attitude change toward the initial mean attitudes of its advantaged members, distilled in Dgj. It is not itself a matter of dialogic inequalities or other asymmetries in the discussion's social interactions, although they presumably affect it. Equivalently, Dgj is also the weighted mean of ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $'s movement toward

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $'s movement toward ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $'s movement toward

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $'s movement toward ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $:

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $:

where ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ = (

$M_{gj}^d $ = (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj2}^d $ −

$\bar{A}_{gj2}^d $ − ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $),

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $), ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ = (

$M_{gj}^a $ = (![]() $\bar{A}_{gj2}^a $ −

$\bar{A}_{gj2}^a $ − ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), and dg ≠ 0 is the proportion of the gth group who are disadvantaged. Note that both

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $), and dg ≠ 0 is the proportion of the gth group who are disadvantaged. Note that both ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and

$M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ > 0 represent movement toward the advantaged or, equivalently, away from the advantaged (assuming, without loss of generality, that

$M_{gj}^a $ > 0 represent movement toward the advantaged or, equivalently, away from the advantaged (assuming, without loss of generality, that ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5 and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ > 0.5 and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $, implying

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $, implying ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $ <

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $ < ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}$).

$\bar{A}_{gj1}$).

But this is not the only possible way of looking at domination qua attitude change. It may thus be clarifying to contrast Dgj with a couple of alternatives. One is the unweighted mean:

the special case of D gj in which dg = ½ for all g. Removing Dgj's dependence on dg does more to contrast ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ and

$M_{gj}^d $ and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $.

$M_{gj}^a $. ![]() ${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ shares Dgj's sign when

${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ shares Dgj's sign when ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $ and

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^d $ and ![]() $\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ move in the same direction but can have the opposite sign when they move in opposite directions (

$\bar{A}_{gj1}^a $ move in the same direction but can have the opposite sign when they move in opposite directions (![]() $M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and

$M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ < 0 or vice versa). If, for example,

$M_{gj}^a $ < 0 or vice versa). If, for example, ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ = 0.4 and

$M_{gj}^d $ = 0.4 and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ = –0.2, Dgj can be negative when the disadvantaged are sufficiently few relative to the advantaged (Dgj = –0.08 for dg = 0.2), but

$M_{gj}^a $ = –0.2, Dgj can be negative when the disadvantaged are sufficiently few relative to the advantaged (Dgj = –0.08 for dg = 0.2), but ![]() ${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ is always positive (in this case,

${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ is always positive (in this case, ![]() ${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ = 0.1), because the disadvantaged are moving further toward the advantaged than the advantaged toward the disadvantaged.

${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ = 0.1), because the disadvantaged are moving further toward the advantaged than the advantaged toward the disadvantaged.

A second alternative, doing still more to contrast ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ and

$M_{gj}^d $ and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $, is

$M_{gj}^a $, is

where Qgj = 1 for ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and = –1 for

$M_{gj}^d $ > 0 and = –1 for ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ < 0.

$M_{gj}^d $ < 0. ![]() ${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ > 0 when the disadvantaged move further toward the advantaged than the advantaged move in that same direction, and < 0 when the disadvantaged move further away from the advantaged than the advantaged move in that same direction. For example, if

${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ > 0 when the disadvantaged move further toward the advantaged than the advantaged move in that same direction, and < 0 when the disadvantaged move further away from the advantaged than the advantaged move in that same direction. For example, if ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ = 0.2, and

$M_{gj}^d $ = 0.2, and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ = 0.4, Dgj and

$M_{gj}^a $ = 0.4, Dgj and ![]() ${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ (= 0.3) both > 0, because the disadvantaged, the advantaged, and ergo the whole group are moving toward the advantaged, whereas

${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ (= 0.3) both > 0, because the disadvantaged, the advantaged, and ergo the whole group are moving toward the advantaged, whereas ![]() ${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ = –0.1, because the disadvantaged are moving less in that direction than the advantaged, whereas if

${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ = –0.1, because the disadvantaged are moving less in that direction than the advantaged, whereas if ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ = −0.2, and

$M_{gj}^d $ = −0.2, and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ = −0.4, both Dgj and

$M_{gj}^a $ = −0.4, both Dgj and ![]() ${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ (= –0.3) < 0, because the disadvantaged, the advantaged, and ergo the whole group are moving away from the advantaged, whereas

${D}^{\prime}_{gj}$ (= –0.3) < 0, because the disadvantaged, the advantaged, and ergo the whole group are moving away from the advantaged, whereas ![]() ${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ = 0.1, because the disadvantaged are moving less in that direction than the advantaged. Appendix C supplies a fuller account.

${D}^{\prime \prime}_{gj}$ = 0.1, because the disadvantaged are moving less in that direction than the advantaged. Appendix C supplies a fuller account.

These alternatives would make sense for more sociometric notions of ‘domination’, comparing subgroup A's influence on subgroup B with B's influence on A. But what we are studying here – what is most relevant to deliberative democracy – is the bottom-line effects on the whole group's attitudes. And for that, Dgj (like Hgj and Pgj) is the best fit – and would be, whether we call it ‘domination’ or something else. (Juliet was right about names.)

Parsing Dgj

It is nevertheless interesting to separate ![]() $M_{gj}^d $'s and

$M_{gj}^d $'s and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $'s contributions to Dgj. Given Equation (4), Dgj > 0 may stem from

$M_{gj}^a $'s contributions to Dgj. Given Equation (4), Dgj > 0 may stem from ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ > 0,

$M_{gj}^d $ > 0, ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ > 0, or both; Dgj < 0 from

$M_{gj}^a $ > 0, or both; Dgj < 0 from ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ < 0,

$M_{gj}^d $ < 0, ![]() $M_{gj}^a $ < 0, or both. The separate means and relative frequencies, in Table 3, evince two interesting patterns. First, the disadvantaged and advantaged move toward each other, each drawing the other's attitudes in their direction (

$M_{gj}^a $ < 0, or both. The separate means and relative frequencies, in Table 3, evince two interesting patterns. First, the disadvantaged and advantaged move toward each other, each drawing the other's attitudes in their direction (![]() $\bar{M}^d$ > 0,

$\bar{M}^d$ > 0, ![]() $\bar{M}^a$ < 0). Second, the advantaged move slightly further toward the disadvantaged than vice versa (on all three dimensions, though not quite as far on the three combined), consistent with the slightly negative

$\bar{M}^a$ < 0). Second, the advantaged move slightly further toward the disadvantaged than vice versa (on all three dimensions, though not quite as far on the three combined), consistent with the slightly negative ![]() $\bar{D}$'s.

$\bar{D}$'s.

Table 3. Parsing domination

Note: ![]() $\bar{D}$,

$\bar{D}$, ![]() $\bar{M}^d$, and

$\bar{M}^d$, and ![]() $\bar{M}^a$ denote the whole group's mean movement toward the initial mean of disadvantaged, its disadvantaged members’ mean movement toward the initial mean attitude of the advantaged, and its disadvantaged members’ mean movement in that same direction.

$\bar{M}^a$ denote the whole group's mean movement toward the initial mean of disadvantaged, its disadvantaged members’ mean movement toward the initial mean attitude of the advantaged, and its disadvantaged members’ mean movement in that same direction. ![]() $\bar{D}^b$,

$\bar{D}^b$, ![]() $\bar{M}^{db}$, and

$\bar{M}^{db}$, and ![]() $\bar{M}^{ab}$ are the relative frequencies with which those means are greater than 0.

$\bar{M}^{ab}$ are the relative frequencies with which those means are greater than 0. ![]() $\bar{D}$ does not necessarily = ½(

$\bar{D}$ does not necessarily = ½(![]() $\bar{M}^d$ +

$\bar{M}^d$ +![]() $\bar{M}^a$), because dg varies across groups and is likely correlated with

$\bar{M}^a$), because dg varies across groups and is likely correlated with ![]() $M_{gj}^d $ and

$M_{gj}^d $ and ![]() $M_{gj}^a $.

$M_{gj}^a $.

Dgj's Dependence on dg

A more extrapolatory question is the extent to which our results might differ for other dimensions of advantage. Let the whole-sample proportion who are disadvantaged be d (which, given random assignment, should be close to the unweighted mean of dg). For the individual advantages we examine here, d ≅ 0.5 – inherently for gender and by virtue of division at the whole-sample median for education and income. As we have argued, these operational thresholds make sense for these advantages. Our results for them are what they are. But what of other advantages, for which d might be much higher or lower? For home ownership in the United States, d < 0.5; for having attended private school in the United States, d > 0.5. Let us therefore consider what ![]() $\bar{D}$ might have been if d had been markedly higher or lower.

$\bar{D}$ might have been if d had been markedly higher or lower.

A simple approach is to estimate a bivariate, linear equation for Dgj as a function of dg. The OLS-estimated slope is small and insignificant, and the R 2 < 0.001, which is already telling. The estimates imply, moreover, that, for dg = 0.2, ![]() $\bar{D}$ = 0.012 for gender, −0.013 for education, −0.007 for income, and −0.014 for all three, while for dg = 0.8,

$\bar{D}$ = 0.012 for gender, −0.013 for education, −0.007 for income, and −0.014 for all three, while for dg = 0.8, ![]() $\bar{D}$ = 0.002 for gender, −0.005 for education, 0.013 for income, and 0.003 for all three.Footnote 22 That is,

$\bar{D}$ = 0.002 for gender, −0.005 for education, 0.013 for income, and 0.003 for all three.Footnote 22 That is, ![]() $\bar{D}$ would still show a bit more opposition than domination but not much of either if the disadvantaged were only 20 percent of each group and slightly more domination than opposition, but next-to-none of either if the disadvantaged were 80 percent of each group. In fine,

$\bar{D}$ would still show a bit more opposition than domination but not much of either if the disadvantaged were only 20 percent of each group and slightly more domination than opposition, but next-to-none of either if the disadvantaged were 80 percent of each group. In fine, ![]() $\bar{D}$ does not appear to depend much on dg.

$\bar{D}$ does not appear to depend much on dg.

Motivated Reasoning Redux

Could the near-zero homogenization, polarization, and domination in our DPs be a mere artefact of motivated reasoning? In everyday discussions, defensive and social approval motivations may limit attitude change, thus reducing Hgj, Pgj, and Dgj and (assuming no correlation between signs and reduction in magnitude) ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$. But this is hardly a convincing explanation for our near-zero

$\bar{D}$. But this is hardly a convincing explanation for our near-zero ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$. DPs are not everyday discussions. Their briefing materials and expert panels afford more information and make uncongenial information harder to ignore. They explicitly cultivate WM, promoting even-handed evaluations, a sense of accountability for one's views, and civic-mindedness, all of which should strengthen accuracy motivations (Bolsen, Cook, and Druckman Reference Bolsen, Cook and Druckman2014; Kam Reference Kam2007; Lerner and Tetlock Reference Lerner and Tetlock1999). They also involve direct interactions with more heterogeneous others, strengthening WM's ability to change attitudes (Mercier and Landemore Reference Mercier and Landemore2012; Tuller et al. Reference Tuller2015), specifically toward their full-consideration counterparts.

$\bar{D}$. DPs are not everyday discussions. Their briefing materials and expert panels afford more information and make uncongenial information harder to ignore. They explicitly cultivate WM, promoting even-handed evaluations, a sense of accountability for one's views, and civic-mindedness, all of which should strengthen accuracy motivations (Bolsen, Cook, and Druckman Reference Bolsen, Cook and Druckman2014; Kam Reference Kam2007; Lerner and Tetlock Reference Lerner and Tetlock1999). They also involve direct interactions with more heterogeneous others, strengthening WM's ability to change attitudes (Mercier and Landemore Reference Mercier and Landemore2012; Tuller et al. Reference Tuller2015), specifically toward their full-consideration counterparts.

In fact, DPs do generally produce considerable attitude change, as our present data make clear (see also, for example, Luskin, Fishkin, and Jowell Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002).Footnote 23 Across our 21 DPs, the mean absolute net change, Mean(|Mean(A ij2 − A ij1)|), is 0.092, and the mean gross change, Mean(Mean(|A ij2 − A ij1|)), 0.203.Footnote 24 Since these numbers may not speak for themselves, consider a simple, artificial scenario that would closely approximate them. Take a familiar five-point, Likert-type scale, with response categories running from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, linearly projected onto the [0, 1] interval as 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1. Let 20 percent of the sample change from neutrality to agreement, another 20 percent from neutrality to strong agreement, and only 24 percent in the opposite direction, from disagreement to strong disagreement. In sum, nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of the sample change their response, nearly a third of them (20 percent of the sample) by two response categories. And two-thirds again as many (40 percent versus 24 percent) change toward 1 as toward 0, doing so, on average, by one-and-a-half times as much (1.5 categories versus 1.0). Here the mean absolute net change is 0.090, and the mean gross change 0.210—numbers within hairs of the 0.092 and 0.203 in our results. So the latter represent quite a lot of attitude change, both gross and net. The reason that ![]() $\bar{H}$,

$\bar{H}$, ![]() $\bar{P}$, and

$\bar{P}$, and ![]() $\bar{D}$ hug 0 is not that the participants are simply clinging to their time-1 attitudes.

$\bar{D}$ hug 0 is not that the participants are simply clinging to their time-1 attitudes.

Deliberative Polling versus other Deliberative Designs

Other deliberative designs do sometimes yield routine and strong homogenization, polarization, and domination. Although there is not yet much systematic evidence on specific design features' effects (notably excepting Karpowitz, Mendelberg, and Shaker Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012), several features characteristic of DPs but rare among other designs do figure to promote WM, inhibit SD, and thus limit homogenization, polarization, and domination (and their opposites). Three, in particular, leap out:

(1) The task being set. Are the participants asked to reach a conscious, collective decision? To reach a consensus? Or simply to talk, listen, learn, and think about the issues? When the goal is consensus, homogenization is a demand characteristic. It is hardly surprising or informative when a design seeking consensus approaches it (consistent with research on compliance and conformity, as in, for example, Cialdini and Goldstein Reference Cialdini and Goldstein2004; Carlson and Settle Reference Carlson and Settle2016). Striving to reach a conscious, collective decision, too, may create incentives to indulge emerging pluralities. Voilà, homogenization. More subtly, the pressure to agree may also hinder WM and allow SD freer rein, thus facilitating polarization and domination as well.Footnote 25 Designs asking the participants only to decide what they individually think entail no such task-based impetus toward homogenization, polarization, or domination.

(2) The encouragement versus discouragement of interim, public expressions of bottom-line attitudes (‘I prefer Policy X’) as opposed to tributary beliefs about likely consequences or valuations thereof (‘Policy X would produce more/less of Y, which would be a good/bad thing because …’). For example, many designs require or encourage publicly tallied votes or shows-of-hands.Footnote 26 This can be regarded as a subtler version of (1), and it, too, may constitute a shove toward homogenization, polarization, and domination (consistent with Brauer et al. Reference Brauer2004; Levy and Sakaiya Reference Levy and Sakaiya2020).

(3) The methods by which the participants are sampled, then assigned to groups. The ideal is random sampling, followed by random assignment, making every group a small random sample. Many designs attempt neither. Random sampling, even when attempted, is never fully realized in practice. Not everyone who is randomly selected can be reached or interviewed, and not everyone interviewed attends the event. Men, the young, the less well educated, and the socially marginal are particularly under-represented. So, still more relevantly, are the least interested in and knowledgeable about the topic. The magnitudes of these biases depend on details like the number of callbacks, the insistence with which anyone besides the designated respondent is excluded, the existence and size of an honorarium, the venue's being away from home, etc. Thus some designs claiming to practice random sampling come reasonably close, while others do not. Even random assignment can vary in attainment. Participants sometimes have their own ideas about what group to join. All this matters because random samples should, on average, across hypothetically iterated sampling, be just as demographically and attitudinally heterogenous as the population from which they are drawn. And the more heterogeneous the groups, the wider-ranging and more balanced the information their members exchange should be – which, as previously argued, should limit homogenization, polarization, and domination (see Levendusky, Druckman, and McLain Reference Levendusky, Druckman and McLain2016 and Strandberg, Himmelroos, and Gronlund Reference Strandberg, Himmelroos and Gronlund2019).

In all these respects, DPs stand apart. They do not task their participants with reaching any conscious, collective decision,Footnote 27 nor urge them toward (or away from) consensus; they sternly discourage interim public expressions of bottom-line opinion, including votes and shows-of-hands; and they employ high-quality random sampling,Footnote 28 followed by thoroughly random assignment, or the closest possible approximations thereof. The recruitment is well-organized and persistent, the participants are offered honoraria, and their travel and lodging are paid for. Small wonder, in this light, that DPs tend to produce much less homogenization, polarization, and domination than many other deliberative designs.

Closing Remarks

Part of this study's value lies in its data. Scattered analyses of individual DPs and other deliberative events have reported broadly similar results regarding homogenization and polarization (Luskin, Fishkin, and Jowell Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002; Fishkin et al. Reference Fishkin2010; Fishkin et al. Reference Fishkin2011; Grönlund, Herne, and Setälä Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2015). In finer grain, Siu (Reference Siu2009) finds that the disadvantaged and advantaged speak about equal numbers of words and for about equal lengths of time, consistent with little domination. But a more convincing test requires a larger number of groups, deliberating on a larger number and wider variety of policy issues, in a larger number and wider variety of contexts. Here we have examined twenty-one DPs, in multiple countries and at different times, encompassing 372 small groups, 139 policy issues, and 2,601 group-issue pairs.

The results show only irregular and feeble homogenization, polarization, and domination. The means are close to 0, the relative frequencies close to 0.5. This is not simply because the participants' attitudes do not change very much, as might be expected from heavily defensive motivated reasoning. They do change, appreciably, just not in ways regularly constituting homogenization, polarization, or domination. This faintness of pattern suggests a relatively deliberative discussion, involving considerable weighing of the merits, rather than just the social dynamics that would yield routine and strong homogenization, polarization, and domination.