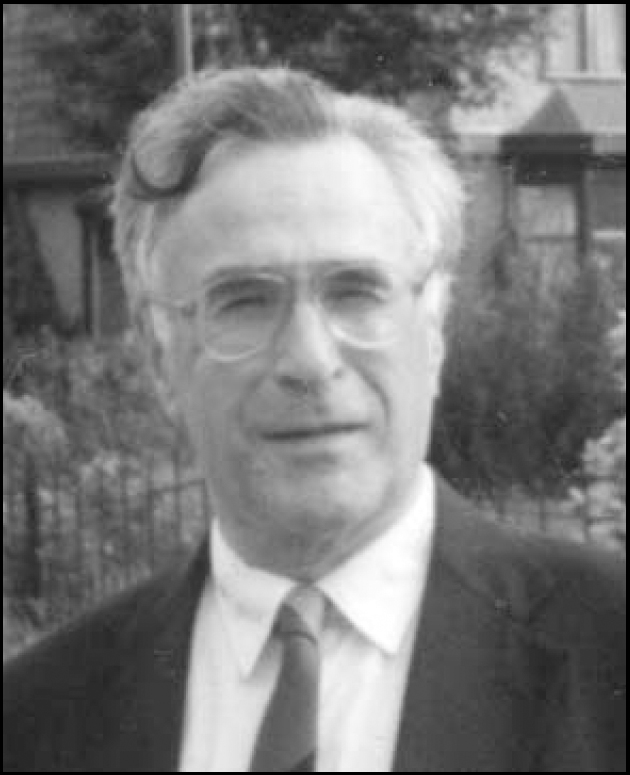

If I sought professional help, Yuri Nuller would have been my choice. This is the best way I can describe Yuri Lvovich Nuller as a person. All other descriptions fall short. To our deep regret, Yuri passed away in his sleep during the early hours of 10 November, 2003, after battling a long and distressing illness.

Yuri Nuller was a kind man. Even when upset about an injustice, he would continue to radiate kindness, while carefully and with a slice of ironic humour trying to explain what in his view was wrong or unjust. Humour was undoubtedly a very important trait that helped him through an interesting yet difficult life. His father, then posted as a senior diplomat at the Soviet Embassy in Paris, was called back to the homeland in 1938 and subsequently executed by the NKVD. The family moved back to their flat in Leningrad. Yuri often told me stories about these years, when the Great Terror swept over the Soviet Union and one neighbour after the others were taken away in the dark of the night, disappearing in the seemingly endless Gulag. These events marked Yuri and, maybe paradoxically, in my view contributed to his gentleness and kindness.

After the war Yuri followed the fate of his father: he was arrested and accused of having been recruited by the French secret service at the age of three, while living in Paris. He was sentenced to a long camp term and sent to the death camps of Kolyma, from which he returned only after the death of Stalin.

I met Yuri for the first time at the end of the 1980s, in Kiev at the house of a common dissident friend. It turned out that we had many friends in common, people connected to the dissident movement in Moscow. Yuri belonged to the ‘second layer’, those who supported the movement and helped political prisoners and their families, but did not sign statements themselves. Yuri was afraid to do so; the 8 years in the Gulag had made him uncertain whether he would be able to survive KGB interrogation or another prison or camp term.

Indeed, Yuri was not only a kind man and a former political prisoner, and a real friend to the people he loved and respected, but also a professor of psychiatry with an excellent international reputation. He was the opposite of a Soviet psychiatrist, with superb clinical skills in which he took the person behind the illness as the focal point of attention and not the diagnosis. In a way he was, again paradoxically, not only the son of a senior Soviet official but also a rare example of the Russian intelligentsia, the same Soviets had tried to exterminate. It was the complete absence of any Sovietism in his nature that made Nuller unique as a Russian psychiatrist and kept him from becoming a leader in his country, which he actually never regretted.

When Yuri fell ill, it was a shock not only to him and his family, but to all who loved him dearly. Years of hope and setbacks followed, but somehow he managed to give his illness a place in his life. Yuri remained the kind, gentle, intellectual but also down-to-earth person he always was. It was an honour to have known him, and it is very hard to lose him as a friend.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.