Childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity are major public health challenges in both their magnitude and consequences. In the USA, data in 2012 showed that more than one-third of children and adolescents were overweight and 18 % were obese( 1 ). In Israeli adolescents, the prevalence was slightly lower, with 13–15 % being overweight and 4–9 % being obese depending on gender and ethnicity( Reference Nitzan Kaluski, Demem Mazengia and Shimony 2 ). Overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence have significant negative impacts on health, which last long into adulthood. Studies have shown that adolescent obesity is associated with increased risk of end-stage renal failure( Reference Vivante, Golan and Tzur 3 ), CVD( Reference Chen, Copeland and Vedanthan 4 , Reference Bjørge, Engeland and Tverdal 5 ) and some types of cancer( Reference Bjørge, Engeland and Tverdal 5 , Reference Levi, Kark and Afek 6 ). A recent Israeli follow-up study has shown that overweight and obesity in adolescence are strongly associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in adulthood( Reference Twig, Yaniv and Levine 7 ).

Lifestyle including dietary change is one of the main causes of overweight and obesity. Among various dietary patterns, the Mediterranean diet (MD) has been accepted as one of the healthiest dietary models in the world. The MD has shown its health benefits in adults by reducing CVD, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers and some neurodegenerative diseases( Reference Serra-Majem, Roman and Estruch 8 , Reference Sofi, Abbate and Gensini 9 ). Meanwhile, the MD is also a common heritage of the culture and tradition in countries around the Mediterranean basin. In 2013, the MD was inscribed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization( 10 ). Nevertheless, against the background of global Westernization and urbanization, a trend of erosion in adherence to the MD is occurring, especially among children and adolescents( Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo 11 ).

On the other hand, the characteristics of eating behaviour in adolescents also affect their dietary patterns. Adolescence is a critical time for the development of eating habits, which are a complex set of behaviours influenced by physiological, psychological, social and genetic factors( Reference Grimm and Steinle 12 ). Disordered eating, as one of the most common chronic conditions in adolescents( Reference Gonzalez, Kohn and Clarke 13 ), influences adolescents’ eating behaviours, thus affecting their diet. Data from an Israeli national survey showed that some 30 % of Israeli girls met the criteria of disordered eating using a modified SCOFF questionnaire( Reference Kaluski, Natamba and Goldsmith 14 ).

Given the high prevalence of overweight/obesity and disordered eating in children and adolescents, as well as the healthy and cultural implications of the MD, it is important to investigate the dietary patterns in adolescents. This is to clarify the dietary features in this key population, identify the high-risk groups and suggest possible interventions for improvement. Since the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED), a tool to evaluate adherence to the MD in children and adolescents, was developed in 2004, it has been widely used in many Mediterranean basin countries, including Spain( Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo 11 , Reference Schröder, Mendez and Ribas-Barba 15 , Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Rivas and Velasco 16 ), Italy( Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi 17 , Reference Roccaldo, Censi and D’Addezio 18 ), Greece( Reference Kontogianni, Vidra and Farmaki 19 – Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki 22 ), Turkey( Reference Sahingoz and Sanlier 23 ) and Cyprus( Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas 24 ). However, adherence to the MD among Israeli adolescents has not yet been described.

To rectify this, the current paper describes the factors associated with adherence to the MD in Israeli adolescents based on an Israeli national youth health and nutrition survey (Mabat Youth Survey, 2003–2004). The data also allow study of possible associations between MD adherence and body weight.

Methods

Population and sampling

The study population, study design and sampling have been described in detail elsewhere( Reference Nitzan Kaluski, Demem Mazengia and Shimony 2 ). Briefly, 6274 schoolchildren in grades 7 to 12, aged 11–19 years, were enrolled into a cross-sectional, nationally representative, school-based study: the Mabat Youth Survey. Self-administered questionnaires including FFQ, eating habits and lifestyle questionnaires were completed by 6274 adolescents, among whom 5268 finished the FFQ. The compliance rate for completion of the FFQ in Jewish and Arab participants was 87·7 and 76·1 %, respectively. Adolescents who were in middle school, who were from low socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds or who did not perform aerobic activity or ball games weekly, had a higher rate of not finishing the FFQ. Five hundred and seventy-eight of the 5268 adolescents who completed an FFQ were also interviewed using the 24 h food recall method. Because the FFQ contained the majority of information on the dietary patterns, only the 5268 adolescents who completed the FFQ were included in the present KIDMED study. The original questionnaire was developed in Hebrew and then translated into Arabic. Data were collected in both Jewish and Arab, religious and non-religious schools. Schools from the Haredi (ultra orthodox) sector or boarding schools were not included.

Data resources

Adherence to the MD in adolescents was assessed using a modified KIDMED index( Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo 11 ). The KIDMED index components were extracted from the self-administered FFQ or eating habits questionnaires. Other data related to the KIDMED index, which were not asked about specifically in the FFQ or eating habits questionnaires, were derived from the 24 h food recalls. Ethnicity (Jews or Arabs) was defined by the location of the school and the language of questionnaires used in the school. SES was taken from the Ministry of Education’s classification of the welfare level of schools based primarily on the socio-economic level of the location. Other demographic and lifestyle factors were determined from answers to the self-administered questionnaires. Anthropometric indicators were measured by trained personnel.

Composite variables

KIDMED score

The modified KIDMED index used in the present study was composed of fourteen items adapted from the original sixteen-item KIDMED index. Items on olive oil usage at home and nut consumption (Table 1, items 15 and 16) were not included, because neither was specifically asked about in the FFQ of the Mabat Youth Survey. Olive oil usage at home was derived from the 578 adolescents who finished an additional 24 h food recall, but nut consumption was not available. Calculation of the modified fourteen-item KIDMED score was applied as shown in Table 1. In the original KIDMED index, three items (items 9, 11 and 12 in Table 1) specifically referred to consumption of designated food categories at breakfast. However, since the FFQ contained no information on meal times, daily consumption of designated food categories was defined as positive in the modified KIDMED index. From the 24 h food recalls, it was found that dairy products (item 11) and commercially baked goods or pastries (item 12) were not typically consumed at breakfast by Israeli schoolchildren. Cereals or grains (item 9) were a major component of breakfast, but were also eaten throughout the day.

Table 1 Definition of the modified KIDMED index used in the Mabat Youth Survey (2003–2004)

KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

The original KIDMED score was classified into three categories: (i) ≥8, good; (ii) 4–7, average; and (iii) ≤3, poor. Based on the fraction of the upper limit to the score range, and the fact that two +1 points were lost in the fourteen-item KIDMED index, we defined cut-off points for the modified fourteen-item KIDMED index as follows: (i) ≥7, good; (ii) 3–6, average; and (iii) ≤2, poor.

BMI

BMI was categorized based on the age- and sex-specific cut-off values of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics 2000 growth charts. Four categories were defined as underweight (<5th percentile), normal weight (5th to 85th percentile), overweight (85th to 95th percentile) and obese (>95th percentile), which was previously described elsewhere( Reference Nitzan Kaluski, Demem Mazengia and Shimony 2 ).

Disordered eating

Disordered eating was assessed using an adapted four-item SCOFF questionnaire compared with the original five-item SCOFF questionnaire, which was used to screen for eating disorders( Reference Luck, Morgan and Reid 25 ). The question on weight loss was modified from original 6·35 kg (1 stone) in three months to 3 kg in our questionnaire( Reference Kaluski, Natamba and Goldsmith 14 ), in order to adapt to the general lower body weight of adolescents as compared with adults. The cut-off point for the four-item screening test was the same as the original one; that is, two or more affirmative answers in the questionnaire was categorized as disordered eating (positive)( Reference Kaluski, Natamba and Goldsmith 14 ).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0. The χ 2 test was used to compare the distribution of KIDMED scores. Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA was used to compare the mean of KIDMED scores. When one-way ANOVA showed significant difference among groups, the Bonferroni correction was used to account for the inflation in Type I error in the multiple comparisons. Adjusted odds ratios were calculated by binary logistic regression. A P value of <0·05 was considered as significant.

Results

Among the 5268 schoolchildren between 11 and 19 years old, 43·5 % (n 2290) were boys and 56·5 % (n 2978) were girls; 50·6 % (n 2665) were in middle school and 49·4 % (n 2603) were in high school; 74·7 % (n 3936) were Jews and 25·3 % (n 1332) were Arabs.

Among the Jewish children, 20·3 % (n 322) of the boys and 15·7 % (n 306) of the girls were overweight or obese; among the Arab children, 23·1 % (n 122) of the boys and 21·7 % (n 159) of the girls were overweight or obese.

KIDMED score by demographic and lifestyle factors

Table 2 shows the distribution of the modified fourteen-item KIDMED scores by school level, gender and ethnicity. Items 1–4 showed that 20–30 % more Arab adolescents than Jewish adolescents consumed fruits and vegetables daily. By contrast, Arabs ate fewer dairy products (items 11 and 13) and more sweets and candies (item 14) than Jews. Regarding eating habits, Arabs consumed more fast foods (as shown in item 6), with the highest rate (73·5 %) in Arab boys in high school, which was more than 30 % higher than that in Jewish boys of the same age group (41·7 %). Girls generally had a 15–20 % higher rate of skipping breakfast than boys, with Jewish girls in high school skipping breakfast the most (44·5 %; item 10). Besides the fourteen items in Table 1, olive oil usage at home was summarized from 578 adolescents from their 24 h food recalls, which showed that 18·1 % (80/443) of Jewish and 71·1 % (96/135) of Arab families used olive oil at home.

Table 2 Distribution of the modified fourteen-item KIDMED index in Israeli adolescents aged 11–19 years by school level, gender and ethnicity; Mabat Youth Survey (2003–2004)

KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

Among 5268 participants, 181 and 100 responses were missing on items 6 and 10, respectively.

Table 3 shows the categorization of the fourteen-item KIDMED scores. Of the total population, 25·5 % (n 1276) had poor, 55·2 % (n 2761) had average and 19·3 % (n 968) had good KIDMED scores. Further analysis by school level, gender and ethnicity showed that Jewish middle-school children had the highest proportion (28·0 % in boys and 28·4 % in girls) with a poor KIDMED score, while Arab middle-school children had the highest proportion (boys 26·9 % and girls 23·2 %) with a good KIDMED score.

Table 3 Categorization of the modified fourteen-item KIDMED scores in Israeli adolescents aged 11–19 years by school level, gender and ethnicity; Mabat Youth Survey (2003–2004)

KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

*P<0·05. **P<0·01.

Table 4 presents the comparison of KIDMED scores stratified by demographic features and selected lifestyle factors. In Jews, high-school children had higher KIDMED scores than middle-school children, and the difference was close to significant in Jewish boys (P=0·053). In contrast, in Arabs, middle-school children had significantly higher KIDMED scores than high-school children (Arab boys P=0·023; Arab girls P<0·001). No significant difference was observed in KIDMED scores between groups according to SES. Mother’s school education (≥12 years) was positively associated with higher KIDMED scores in all the groups, with a significant difference in Jewish boys (P=0·012) and Jewish girls (P=0·001). Both Jewish boys and Arab boys who smoked had lower KIDMED scores than those who did not, and the difference was statistically significant in Arab boys (P=0·027). In all the groups, students who performed aerobic activity or ball games weekly had higher KIDMED scores than their comparison group, with significance in Jewish boys (P=0·009). Watching television/videos or listening to music for ≥2 h/d was significantly associated with poorer KIDMED scores in all groups. Children who always/often read food labels consistently had better KIDMED scores than children who sometimes/don’t read food labels, and the difference was significant in Jewish boys, Jewish girls and Arab boys. In Jewish boys, one-way ANOVA showed that body weight was associated with KIDMED score (P=0·021); a further post hoc Bonferroni test revealed that the real difference existed between the underweight group and the normal weight group (P=0·032).

Table 4 Modified fourteen-item KIDMED scores in Israeli adolescents aged 11–19 years by demographic features and lifestyle factors; Mabat Youth Survey (2003–2004)

KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

*P<0·05, **P<0·01.

Explanatory factors of KIDMED score

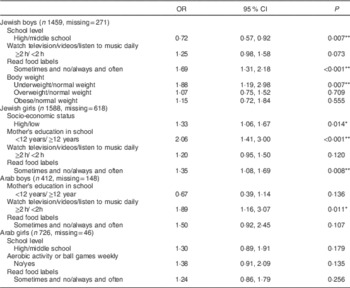

Table 5 shows the adjusted odds ratios for having poor KIDMED scores by gender, ethnicity and selected lifestyle factors.

Table 5 Adjusted odds ratios of having a poor KIDMED score (v. average/good) among Israeli adolescents aged 11–19 years by gender, ethnicity and lifestyle factors; Mabat Youth Survey (2003–2004)

KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

*P<0·05, **P<0·01.

In Jewish boys, being in high school was negatively associated with having a poor KIDMED score (OR=0·72; 95 % CI 0·57, 0·92). Watching television/videos/listening to music for ≥2 h/d, sometimes/not reading food labels and being underweight were positively associated with having a poor KIDMED score, with statistical significance for sometimes/not reading food labels (OR=1·69; 95 % CI 1·31, 2·18) and being underweight (OR=1·88; 95 % CI 1·19, 2·98). Overweight and obesity were not explanatory factors for having a poor KIDMED score.

In Jewish girls, SES, mother’s school education, sedentary lifestyle and reading food labels were associated with adherence to the MD. The odds of having a poor KIDMED score was significantly higher in groups who had higher SES (OR=1·33; 95 % CI 1·06, 1·67), whose mother’s years of education was <12 years (OR=2·06; 95 % CI 1·41, 3·00) and who sometimes/don’t read food labels (OR=1·35; 95 % CI 1·08, 1·69).

In Arab boys, watching television/videos/listening to music for ≥2 h/d and sometimes/not reading food labels were associated with having a poor KIDMED score. The odds of having a poor KIDMED score if watching television/videos/listening to music for ≥2 h/d was 1·89 times higher than that of the comparison group in Arab boys.

In Arab girls, no aerobic activity or ball games weekly or sometimes/not reading food labels were associated with a poor KIDMED score, but without statistical significance.

A further analysis into reading food labels showed that the proportion always/often reading food labels was significantly higher in girls than in boys (52·4 v. 39·6 %, P<0·001). A higher percentage of Arab children always/often read food labels than Jewish children (57·5 v. 43·2 %, P<0·001). When stratified by school level and ethnicity, the proportion of always/often reading food labels in girls was always significantly higher than that in boys (Fig. 1(a)).

Fig. 1 The proportion of Israeli adolescents aged 11–19 years who always/often read food labels by gender, ethnicity, school level and selected factors; Mabat Youth Study (2003–2004). Always/often reading food labels was significantly associated with (a) gender (

![]() , boys;

, boys;

![]() , girls), (b) body weight (

, girls), (b) body weight (

![]() , underweight;

, underweight;

![]() , normal weight;

, normal weight;

![]() , overweight/obese) and (c) dieting (

, overweight/obese) and (c) dieting (

![]() , no dieting;

, no dieting;

![]() , dieting): *P<0·05, **P<0·01

, dieting): *P<0·05, **P<0·01

When analysing the association between reading food labels and body weight, the proportion always/often reading food labels in the overweight/obesity group was almost always higher than that in the normal weight group, except in Arab boys in middle school (Fig. 1(b)). After stratification by gender, ethnicity and school level, the number of cases in the underweight category (<5th percentile BMI) in some Arab groups was as small as less than ten. Therefore, the rate of reading food labels in underweight group in Arab children might not be reliable.

Dieting was also shown to be associated with frequency of reading food labels. Generally, adolescents who were dieting were more likely to always/often read food labels. The difference in the rate of always/often reading food labels between those who were and were not dieting was greater in Jews than in Arabs (Fig. 1(c)).

KIDMED score and disordered eating

When comparing the fourteen-item KIDMED scores between disordered eating (+) and disordered eating (−) groups, no difference in KIDMED scores were observed between the two groups when stratified by gender and ethnicity (data not shown).

Discussion

The present paper is a first attempt to describe the adherence to the MD using a modified KIDMED index in Israeli adolescents based on a nationwide health and nutrition survey – the Mabat Youth Survey. It has described the dietary patterns in Israeli adolescents, identified the high-risk group in terms of poor quality of eating and eating habits, and provided the direction for intervention programmes.

KIDMED distribution

The compliance to the MD was not very satisfactory in Israeli adolescents when compared with other youth populations of comparable age around the Mediterranean basin region. The overall distribution of fourteen-item KIDMED scores in the present study was that 25·5 % of the total participants had poor, 55·2 % had average and 19·3 % had good adherence to the MD. In other populations, Spanish children and adolescents seemed to have the best adherence to the MD, with only 2–7 % having a poor and 30–50 % having a good KIDMED score, according to different studies( Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo 11 , Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Rivas and Velasco 16 , Reference Grao-Cruces, Nuviala and Fernández-Martínez 26 ). Surveys in other countries, including Greece( Reference Kontogianni, Vidra and Farmaki 19 ), Turkey( Reference Sahingoz and Sanlier 23 ) and the Balearic Islands( Reference Bibiloni Mdel, Pons and Tur 27 ), demonstrated that the percentage of poor adherence to the MD at comparable ages ranged from 15 to 27 %, while the proportion of good compliance to the MD was between 8 and 28 %. In spite of the difference in cut-off values of KIDMED categories due to two missing items in the present study, the high proportion of poor adherence to the MD in Israeli adolescents was still alarming. It should be noted that the adolescents who completed the FFQ and thus were included in the KIDMED study represented 87·7 and 76·1 % of the Jewish and Arab participants in the Mabat Youth Survey, respectively. Further analysis showed that the non-completers tended to be in middle school, with low SES and did not engage in physical activity regularly. Therefore, the true adherence to the MD in Israeli adolescents may be even less than the present data have shown. Geographically, Israel is in the Mediterranean basin; however, the diversity of the population in terms of ethnicity, religion, origin of immigration, family structure and more, may lead to a weaker tradition in compliance to the MD, which may explain the poor adherence to the MD in the present study.

Further, looking at the KIDMED score distribution by school level, gender and ethnicity, Jewish middle-school children were identified as a high-risk group for low adherence to the MD, with an overall rate of having a poor KIDMED score of 28·2 % (similar in boys and girls, Table 3). This was mainly attributable to less fruit and vegetable consumption, and more skipping breakfast (Table 2). Therefore, intervention programmes aimed at reversing these trends should be developed to improve the dietary quality and eating habits of this high-risk group.

Factors associated with KIDMED score

School level was inconsistently associated with KIDMED score between Jews and Arabs. Arab high-school children had poorer adherence to the MD than Arab middle-school children in terms of both the proportion of having a poor KIDMED score (Table 3) and the mean of KIDMED scores (Table 4). The trend disappeared in Jewish girls, and even reversed in Jewish boys (Tables 3 and 4). In other studies, the association between compliance to the MD and age, which was represented by school level in our study, was not consistent in different populations. A negative association between age and KIDMED score was found in most studies, including among Greek( Reference Kontogianni, Vidra and Farmaki 19 , Reference Bargiota, Pelekanou and Tsitouras 21 , Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki 22 ), Spanish( Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Rivas and Velasco 16 ) and Balearic Islands( Reference Bibiloni Mdel, Pons and Tur 27 ) schoolchildren. In fewer studies, KIDMED score did not differ among age groups( Reference Farajian, Risvas and Karasouli 20 , Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas 24 ), although the age groups were not exactly the same as those in the present study. In addition to the effect of age, school education may also play a role in the trend of adherence to the MD by school level.

Mother’s education was positively associated with better adherence to the MD in all groups of our study population (Table 4). In Jewish girls, the mother having less than 12 years of school education was the strongest explanatory factor for having a poor KIDMED score (Table 5). Similar findings were also observed in Spanish( Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo 11 ), Greek( Reference Kontogianni, Vidra and Farmaki 19 ), Balearic Islands( Reference Bibiloni Mdel, Pons and Tur 27 ) and Turkish( Reference Sahingoz and Sanlier 23 ) adolescents, highlighting the influential impact of mothers’ education on their children, which should also be a focus for intervention.

Physical activity and sedentary lifestyle, as expected, showed opposite associations with the KIDMED scores. Performing aerobic activity or ball games weekly, and watching television/videos or listening to music for <2 h/d were consistently associated with better adherence to the MD (Tables 4 and 5). Such associations between physical activity, sedentary lifestyle and the KIDMED score have also been suggested in other studies( Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki 22 , Reference Santomauro, Lorini and Tanini 28 , Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala 29 ). In a study on adolescents in Tuscany, with a sample size of 1127, the odds ratio for having a poor KIDMED score increased monotonically when frequency of physical activity decreased or time spent on sedentary activity increased, showing the consistency of the association( Reference Santomauro, Lorini and Tanini 28 ).

Since SES was classified based on the location of schools, without assessment at the individual level, the analysis by SES might be not reliable. This might explain the finding that, in Jewish girls, high SES was associated with poor adherence to the MD.

Reading food labels and KIDMED score

Always/often reading food labels was positively associated with better adherence to the MD in all study groups after stratification by gender and ethnicity (Tables 4 and 5). However, previous studies showed that reading food labels did not always translate into healthy food choices directly( Reference Auchincloss, Young and Davis 30 ). One possible reason for our positive finding may be the facilitating role of nutrition knowledge in the association between reading food labels and better dietary quality. Evidence has shown that people who have better nutrition knowledge can utilize food label information better and make healthier food choices( Reference Auchincloss, Young and Davis 30 , Reference Miller and Cassady 31 ). Another possible explanation is that the sub-populations who may be more conscious about their body weight, such as female students, heavier students and those who were dieting, may be more careful about their diets and therefore more likely to read food labels. In the present study, our data support the claim that these sub-populations do indeed read food labels more frequently (Fig. 1), but do not necessarily have higher KIDMED scores (Table 4). Because of the cross-sectional study design, the temporality of reading food labels and adherence to the MD was not known. Regardless of the pathway, for the positive association between reading food labels and better adherence to the MD, from the public health policy point of view, some facilitating factors should be considered to transform food label reading into healthy dietary choices and practices, such as providing key points of nutritional knowledge on the package, promoting reader-friendly food labels and advertising, etc.( Reference Auchincloss, Young and Davis 30 ). Also, psychological and social factors that affect eating behaviours in adolescence should also be considered.

The proportion of reading food labels among the Arab students was higher than that in the Jewish ones (Fig. 1(a)). This result was counter-intuitive, because Israeli law requires labelling in Hebrew only, which may have created some barriers in understanding food labels. A possible reason for the positive association was the differential selection bias between Jews and Arabs in the current KIDMED study. Among the national representative samples in the Mabat Youth Survey, the proportion of Jews and Arabs who completed the FFQ, thus being enrolled in the KIDMED study, was 87·7 and 76·1 %, respectively. The non-completers had a significantly higher percentage of being in middle school or from a low-SES background, who would be less likely to read food labels frequently. Another possible reason was a social desirability bias( Reference Fisher and Katz 32 ). Since the questionnaires were self-administered, participants may tend to give the expected answers to various extents depending on demographic, psychological and other factors. Because of the possible selection bias (rate difference in completing the FFQ between Jewish and Arab students) and the response bias (social desirability bias), the direct inter-ethnic comparisons might be not valid.

Overweight/obesity and KIDMED score

Overweight/obesity was not associated with adherence to the MD in the present study (Tables 4 and 5), which was consistent with studies in Greece( Reference Farajian, Risvas and Karasouli 20 , Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki 22 ). In contrast, some studies have shown that overweight/obesity was associated with a higher KIDMED score( Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi 17 , Reference Santomauro, Lorini and Tanini 28 ), whereas another study found a negative association between obesity and the KIDMED score( Reference Schröder, Mendez and Ribas-Barba 15 ). These contradictory results demonstrate the complexity of this question. One explanation is the mediating effect of parents’ educational status: a study in Greece showed that adherence to the MD in adolescents was inversely associated with children’s obesity status only in families where parents had a higher educational level( Reference Antonogeorgos, Panagiotakos and Grigoropoulou 33 ) . On the other hand, these inconsistencies might reflect certain drawbacks of the KIDMED index, which focuses only on dietary quality and healthy eating behaviours without considering the quantities of food consumed, and is therefore limited in its ability to predict overweight/obesity-related health outcomes.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to the present research. The main one was that the Mabat Youth Survey in general, and the FFQ in particular, was not specifically developed for the purpose of calculating a KIDMED score. Therefore, there were some necessary compromises in translating the data generated from the Mabat Youth Survey questionnaires to the KIDMED score, which could affect the comparability of our results with other KIDMED studies. However, we think that using fourteen of the sixteen questions with appropriate scaling still gave meaningful results. Second, the rate of completing the FFQ and thus being included in the current KIDMED study among the participants in Mabat Youth Survey was significantly higher in Jews than in Arabs (87·7 v. 76·1 %). This differential selection bias may influence the inter-ethnic comparisons. Third, the Mabat Youth Survey questionnaires were self-administered, which may cause the respondents to over-report socially desirable responses (social desirability response bias). Fourth, the SCOFF questionnaire was validated extensively in females, particularly in females more than 18 years old, but the validity test in boys was limited. Lastly, the data presented here relate to the year of 2004. The new Mabat Youth Survey, carried out in 2015–2016, will provide a new data set. Then the methodology discussed herein can be used and will allow following of time trends, which it is hoped will show an improvement in adherence to the MD.

Conclusions

In general, Israeli adolescents had poor adherence to the MD, especially among Jewish middle-school students. Interventions aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary time, improving mother’s education, promoting and facilitating reading of food labels are suggested, in order to improve nutritional status and promote the health of schoolchildren. Further research on the effectiveness of interventions targeting different factors in each sub-population might be needed. The time trend of dietary pattern transition in adolescents also should be investigated.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: This work was presented as part of the requirements of the International MPH programme in Braun School of Public Health, Hebrew University – Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem. The authors are very grateful to Dr Mario Baras for kind statistical advice. They would also like to thank the Israel Center for Disease Control and the Ministry of Health, who conducted the survey together. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All the authors participated in conceptualizing and designing the study; W.P. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; R.G. and E.M.B. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript critically. Ethics of human subject participation: According to Ministry of Education guidelines, those students whose parents did not oppose, in writing, the participation of their children, were included in the survey, and given the self-administered questionnaire to complete.