Video games are one of today's quintessential media and cultural forms, but they also have a surprising and many-sided relation with the past (Morgan Reference Morgan2016). This certainly holds true for Sid Meier's Civilization (MicroProse & Firaxis Games 1991–2016), which is a series of turn-based, strategy video games in which you lead a historic civilization “from the Stone Age to the Information Age” (Civilization ca. 2016). Sid Meier's Civilization VI, the newest iteration of the series developed by Firaxis and released on October 21, 2016, allows players to step into the shoes of idealized political figures such as Gilgamesh, Montezuma, Teddy Roosevelt, and Gandhi. Via these and other leaders, you aim to achieve supremacy over all other civilizations. This is done through founding cities, creating infrastructure, building armies, conducting diplomacy, spreading culture and religion, and choosing “technologies” and “civics”—philosophical or ideological breakthroughs—for your civilization to focus on. In this way, Sid Meier's Civilization series, often simply referred to as Civ, allows players to engage with past and present technological advances, social systems, and built heritage in a playful history that is closely analogous to but always slightly different from our own (Figure 1). In this review, we provide a brief overview of the series and some of the new features present in Civ VI. We also question Civ’s treatment of world history and heritage and place the series in a broader perspective as a cultural and ideological artifact, entangled with changing perceptions and politics of the past.

Figure 1. Screenshot from Civilization VI. Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke playing as Harald Hardrada of Norway, upon achieving a cultural victory. Around the capital Nidaros, a number of wonders can be seen, such as the Great Lighthouse, the Colossus, Alhambra, the Terracotta Army, the Hanging Gardens, and the Hermitage.

CIV'S HISTORY AND HERITAGE

As you are reading this review, between 50,000 to 90,000 people are busy building their empires, one turn at a time, in Civ V or Civ VI (SteamSpy 2017a; SteamSpy 2017b). Since its debut, the Civ series has sold more than 37 million copies worldwide and, together, players have played over one billion hours across all versions (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2016). Its roots lie with developer and publisher MicroProse in Maryland, USA, where in 1991 Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley launched what would become one of the most recognizable and critically acclaimed franchises in the video game industry. Civ I became so popular that it gave rise to a whole genre of strategy video games known as 4X. In 4X games, players control an empire, state, or other large political unit through gameplay that is based on an iteration of “eXploration,” “eXpansion,” “eXploitation,” and “eXtermination.”

These elements are present in all subsequent Civ games, with every entry in the series making its own tweaks to this basic formula. As a result, Civ rewards long-term planning and features evolution-like, phased gameplay. The moment-to-moment mechanics that allow for this careful strategizing are facilitated by a turn-based system in which the player will manage resources and make political decisions. In one turn, a player may be confronted with diplomatic talks with Napoleon, give building orders for the construction of the Pyramids, choose whether to research mathematics or iron working, and send her scouts to explore uncharted territory.

Every game in the series features a “Civilopedia” that provides informative entries on all aspects of the game. These not only provide descriptions of in-game effects, but also provide information about the actual history underlying every building, wonder, unit, leader, technology, and more. Still, for people new to the series, starting up a first game of Civ can present somewhat of an overwhelming experience—which is mitigated to some extent in Civ VI by an extensive tutorial that pits the Sumerians against the Egyptians.

For those who are already acquainted with Civ, this newest iteration builds on the core of the series with some innovative features. In contrast to previous games, in which urban building was restrained to a player's city centers, Civ VI shifts the focus to the ecology of the wider landscape. Players need to zone plots adjacent to cities by developing them as commercial, residential, cultural, industrial, and other types of districts, which receive strategic bonuses from being built close to specific types of environments and other districts. Civ VI has also taken a leaf from quest-driven games with its introduction of “Eureka moments” that give the game a new strategic element, the completion of which will speed up the discovery of new technologies and civics. For example, the first meeting with another civilization will give the player a boost to the discovery of the “Writing” technology, which unlocks the option to build libraries and campuses. The diplomacy of computer-controlled leaders of other civilizations, known for largely predictable behavior interspersed with irrational decisions, has long been a thorn in the side of players (Figure 2). Civ VI now more clearly flags the quirks of other leaders, but their actions toward you and other opponents controlled by the computer can still feel erratic.

Figure 2. Gandhi declares war in Civilization I. Gandhi is one of the most pacifist leaders in the game, but thanks to a bug in the original game he is also one of the most likely to use nuclear weapons. This behavior was retained as an in-joke in later games, leading to a plethora of online memes about Gandhi's penchant for creating nuclear holocausts.

Civ has always had a colorful and clear graphic design, but Civ VI sports a particularly polished look. Tweaking graphical settings will make it perform on slightly older PCs, as well. Top marks go to sound design with an impressive game score that takes iconic compositions from one of the game's civilizations and evolves them from single instrument to full orchestra as the player continues through the ages. With generally favorable reviews and two million units sold in the first two weeks after its release, the game is already a critical and commercial success (Plunkett Reference Plunkett2016; SteamSpy 2017c; Zucchi Reference Zucchi2016). In short, over the next few years, millions of veterans and newcomers will experience our world's heritage and history viewed through the lens of Civ VI’s developers and designers.

POLITICS OF THE VIRTUAL PAST

As an exercise in interactive history-telling, Civ VI and its forebears have a complex relationship with the past. A regular game of Civ VI starts at the “dawn of civilization” at 4000 B.C., with the founding of a capital city for every player and computer-controlled opponent. Likewise, the game always ends in similar ways, with one of four types of “victory”: military, religious, cultural, or technological domination. The technology tree starts with “Pottery,” “Animal Husbandry,” and “Mining” and through relatively tightly prescribed pathways leads to “Robotics,” “Nuclear Fusion,” and “Nanotechnology.” The civics tree starts with “Code of Laws” and has “Globalization” and “Social Media” as its epitome—one can only hope the designers were having a laugh when they envisioned tweeting and Facebooking to be the new pinnacle of civilization.

When it comes to this cookie-cutter approach to societal and cultural change, it has to be noted that Sid Meier, the series’ creative father, is regarded by his peers as one of the most brilliant game developers (Crossley Reference Crossley2009). The first Civ game Meier created was based on what he remembered from his family's subscription to American Heritage and what historical atlases and books he could scrounge from local libraries. Yet it is perhaps a lack of interest in the finer intricacies of the past that drove and continues to drive the design of Civ. Indeed, Meier meant and means for Civ to be an “apolitical game,” or, as he stated in a recent interview: “one of our fundamental goals was not to project our own philosophy or politics onto things. Playing out somebody else's political philosophy is not fun for the player” (Tharoor Reference Tharoor2016).

The idea of “apolitical fun” has big implications for Civ’s gameplay and the type of interactive experiences it presents its players with. The result of Meier's mollycoddling is that it undercuts the potential for an honest engagement with the past that is, in principle, present in a game like Civ. For example, wars are waged between units that look more like small miniatures than actual combatants, fought with only battle cries and some clatter of arms. City sizes, indicated with single or double digits, drop a few points to indicate the massive loss of life after a successful siege. Slavery, one of actual world history's darkest pages, as well as a practice that has had great societal, cultural, demographic, and economic impacts, did not appear in the series until Civilization IV. Civilization V did away with it, as well as with the series’ long-standing feature of global warming and pollution caused by ecologically destructive behavior. Civilization VI continues this clean—we would argue too clean—view of historical societies and cultures.

In 1991, the idea of an apolitical yet interactive version of history at the “end of history” must have sounded less ridiculous (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1992). The result of this is a series of games that is perhaps more palatable for a large audience with a range of sensibilities, but at the cost of projecting a false reality. Moreover, we argue that a more political stance does not necessarily hinder enjoyment of a game. As the popularity of such titles as Never Alone (Upper One Games 2014), Prison Architect (Introversion Software 2015), This War of Mine (11 Bit Studios 2015), and Undertale (Toby Fox 2015) shows, players are quite capable of dealing with even highly politically or philosophically charged interactive media. Instead, the lack of a clearly defined politics of the virtual past has opened Civ up to the risk of replicating dominant narratives of what it means to create or have “civilization.” Simply put, the enterprise of making a game about civilization is inherently a political philosophical undertaking.

THE WONDERS OF CIVILIZATION

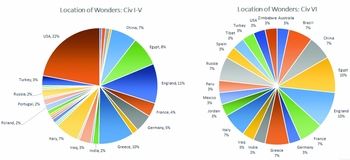

An in-depth look at the “building blocks” of civilization in Civ—the technologies, buildings, and civics—makes it immediately clear that these games have largely perpetuated a traditional narrative of what it means to have civilization. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Civ’s “wonders,” a collection of unique buildings and projects that are closely analogous to the concept of World Heritage. An overview of the wonders in Civ’s main games (Figure 3) shows a core group that have appeared in (nearly) all versions. These core wonders are the video game equivalent of an old-fashioned world history atlas, like the one Meier used to consult for the first Civ. Starting with ancient, Orientalist wonders like the Hanging Gardens and the Pyramids, we continue our traditionalist interactive world heritage tour through Classical Greece, via Renaissance and Industrial Europe, and end it with “marvels” of the modern era like the Pentagon and the Manhattan Project. An additional breakdown of the actual location and main cultural identity of wonders across Civ I through Civ V makes it clear that there is an overwhelming focus on Western and Orientalist heritages (Figure 4a).

Figure 3. A two-mode network showing how wonders are distributed over all six main Civilization games. At the center, the core of wonders present in most or all of these games.

Figure 4. Pie chart with a breakdown of the nations from which the actual versions of the wonders in (a) Civilization I through Civilization V and (b) Civilization VI can be found.

There is some reason for optimism, however. In the list of wonders in Civ VI, we see several new wonders as well as more variety in their actual world locations (Figure 4b). Interestingly, many of these are referred to in the original language of the culture they are associated with. For instance, the Templo Mayor, or Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, has been added to the game under its Nahuatl name: Huey Teocalli. We suggest that this change in direction is the result of new attention to indigenous languages and heritages, a movement that has a long(er) history in politics and academia, but which now seems to have made its mark on a mainstream game like Civ. The introduction of a more diverse set of world heritages, as well as the new naming convention, seems to suggest that the game's design is not as impervious to changing cultural sensibilities as its intellectual father might suggest.

From the perspective of the archaeological and heritage disciplines, this may well be the true innovation of Civ VI, even more so than the inclusion of “archaeologists” as units and “museums” as buildings. Beyond being merely a sign of the times, the inclusion of heritage in a game as popular as Civ has an impact outside the game. As proof, the date of the prerelease reveal of the Aztec culture and the date of the release of the game itself show an upsurge in popularity of Google searches on “Huey Teocalli” and other new wonders (Figure 5). These are certainly steps in the right direction, but for the upcoming expansions of Civ VI or an eventual Civ VII, we would like to see a more avant garde and multi-vocal engagement with history as event and process and an even wider inclusion of our world's cultural, natural, and intangible heritage.

Figure 5. Graph showing the increase in number of searches in Google for the term “Huey Teocalli.” A peak is visible in the middle (announcement of the inclusion of the Aztecs in Civilization VI) and on the right (release of Civilization VI; data from Google Trends).

CONCLUSION

When a player in Civ VI discovers the “Cultural Heritage” civic, she is greeted with the words of Marcus Garvey: “a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” In a very real sense, 25 years of Civ have helped millions of people gain knowledge of human history, origins, and culture through a playful and interactive engagement with the past. However, even if Civ VI has some new sensibilities when it comes to the representation of the past as well as a much expanded Civilopedia, this game is not a good replacement for World History and Heritage 101.

It is, however, a medium and artifact that merits more attention by the archaeological and heritage disciplines. There are many routes of approach here; writing reviews in scholarly journals is just one of them. For instance, those who are experienced with the core game of Civ could try the mods and scenarios that allow you to experience specific periods in the past or even aim to build your own scenarios and mods. In addition, you could try to go beyond the tight confines of its design and experiment with new approaches to play, such as pacifism.

For those who have never played Civ, there is no better time than the present to pick up this game. If you do, the authors of this review are not liable for nights spent building empires until the early morning and any missed deadlines that may ensue.