Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common chronic disease affecting in excess of 180 million people worldwide, and the number will double by 2030, to around 366 million (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2006). Ongoing structured patient education is a core requirement within UK national and international diabetes health policy (Declaration of the Americas, 1999; Rutten et al., Reference Rutten, Verhoeven, Heine, De Grauw, Cromme, Reenders, Van Ballegooie and Wiersma1999; Finnish Diabetes Association, 2000; Department of Health, National Service Framework for Diabetes (NSF) Standards, 2001; Diabetes UK, 2003; International Diabetes Federation, 2003; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2003). Structured patient education aims to empower patients by improving knowledge and skills towards effective, confident self-care. In the United Kingdom (UK), where DM affects 2.3 million people (Diabetes UK, 2007), black and ethnic minority peoples, and poor and socially disadvantaged groups are especially vulnerable to the effects of the disease (Department of Health NSF, 2001).

In the UK, it is recommended that all patients with diabetes be offered structured education at the time of diagnosis and ongoing, based on a formal assessment of need (NICE, 2003). Systematic review evidence offers a cautious indication that education has a beneficial impact on health and quality of life (Norris et al., Reference Norris, Engelgau and Narayan2001; Deakin et al., Reference Deakin, Mcshane, Cade and Williams2005), and this is reinforced in recent UK trials of structured education (Deakin et al., Reference Deakin, Cade and Williams2006; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Heller, Skinner, Campbell, Carey and Cradock2008; Sturt et al., Reference Sturt, Whitlock, Fox, Hearnshaw, Farmer, Wakelin, Eldridge, Griffiths and Dale2008). The most recent review (Loveman et al., Reference Loveman, Frampton and Clegg2008) reveals mixed results, with little evidence to suggest whether or how educational programmes might be directed to achieve maximal benefit for patients with type 2 diabetes. Ongoing education for the majority, who have lived with diabetes for many years, is in its infancy. The Healthcare Commission (2007) reported that only 11% of people with diabetes surveyed had accessed diabetes education. This lack of access is related to both provision and uptake, and more qualitative research is recommended to explore areas such as patient motivation to attend (Lucas and Roberts, Reference Lucas and Roberts2005). Individuals who have never been exposed to diabetes education may have difficulty articulating what they need to know and how best they can learn, when planning preferences for future education (Benavides-Vaello et al., Reference Benavides-Vaello, Garcia, Brown and Winchell2004). Other people, often white and male, recruited from a population likely to be well educated in general terms, are able to articulate and justify their own diabetes educational requirements (Sturt et al., Reference Sturt, Hearnshaw, Barlow, Hainsworth and Whitlock2005a).

Methods

Aims

This paper is written from a broader study, carried out for a master’s dissertation, looking at the attitudes of hard-to-reach groups, towards ongoing diabetes education and self-management. The aim of this paper is to explore the data specifically relating to attitudes towards ongoing diabetes learning, in those from different cultural backgrounds, including black and ethnic minority groups.

Setting

The primary care setting was an inner-city general practice, with a list size of 5800, in Nottingham, UK. Nottingham city was ranked seventh, in the most deprived local authorities in England (Nottingham Research Observatory Ltd, 2004). The practice covers a population with a high ranking in the 2004 indices of deprivation ID data tables (Nottingham Research Observatory Ltd, 2004). Those from the practice with type 2 diabetes included black and ethnic minorities, and the socio-economically disadvantaged, but not exclusively so. Diabetes education offered at the practice consisted of discussions within consultations, and two diabetes open mornings held within the previous two years.

Participants and recruitment

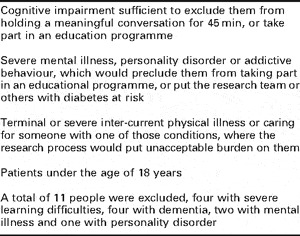

In January 2006, 171 people with type 2 diabetes who had been diagnosed for over one year and were over 18 years of age were registered with the practice. Eleven of these 171 were excluded; Table 1 explains the reasons for exclusion. The recruitment strategy required two stages. Firstly, in order to comply with the Data Protection Act (1998), a single letter of invitation was sent to the remaining 160 people, asking them to opt in to the research process and be available to be considered for recruitment into the study. Alternatively, they could opt out and not be contacted further (Data Protection Act, 1998; Hewison and Haines, Reference Hewison and Haines2006; Kalra et al., Reference Kalra, Gertz, Singleton and Inskip2006). The letter was signed by the practice manager to distance the author HP from the recruitment process and any coercion to take part. Posters were displayed in English within the practice, also asking for people to opt in to the research process and be considered for recruitment. Secondly, purposive, non-random sampling was undertaken on those who had opted in (Mays and Pope, Reference Mays and Pope1996). It was hoped to interview chosen people of different ages, gender and cultural backgrounds, and those experiencing social disadvantage such as refugees or those with learning disabilities or from care homes, from those who had opted in.

Table 1 Exclusion criteria

There was a low response rate with 19 people responding. Eleven positive opt in replies (6.9%) were received, with few from the target populations. Nine were males (all white; seven out of nine over 70 years); two were females (one white, one African-Caribbean, both over 70 years). Eight people replied to opt out and declined further participation. A total of 141 people did not reply, including most from the target populations. Purposive sampling was carried out on the 11 positive replies, as follows. The first reply received (white male, over 70 years) was recruited to pilot the interview schedule. The two females were recruited. As all three participants so far were over 70 years, the youngest white male was additionally chosen to collect data from a wider age range.

The recruitment strategy was deemed unsuccessful with only four participants and little cultural, age or other variation. Hence, one trained administrator made targeted, verbal and telephone approaches opportunistically, when people telephoned or visited the practice. From the 141 who had not replied to the initial letter, she was given lists of black and ethnic minorities by gender and age, to try and encourage them to opt in. Only four more people opted in. Hence all of them were chosen; there was further purposive sampling as they had been pre-selected by age, gender and ethnicity. This brought the total number of participants to eight (Table 2). Time constraints meant that no other hard-to-reach, socially disadvantaged or non-English-speaking participants were sought. The sample remained small and was not fully representative of the practice population.

Table 2 Participants with identifier, showing age, gender and ethnicity, total = 8

Procedures

Interviews

An interview schedule (Table 3) was developed following a review of the literature and consultation with the Warwick Diabetes Research & Education User Group (WDREUG). This is a body of people living with diabetes who meet bi-monthly with researchers to review and contribute to both emerging and ongoing diabetes research within the Medical School. Their role is widespread across the research process and they form an established part of the research infrastructure (Lindenmeyer et al., Reference Lindenmeyer, Hearnshaw and Sturt2007). The interview questions reflect the wider aims of the original study, but were aimed at generating quality data concerning ongoing diabetes learning in different informal and formal contexts. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken in the practice or the participant’s home, using the interview schedule (Table 3) as a guide, with opportunity for elaboration and additional questions emerging as the interview proceeded. The interview schedule was pilot tested on the first participant and the schedule did not change substantially as a result. The first question about job-related learning was intended to provide a non-threatening early opportunity to explore education; school-related learning was avoided in case it had been a negative experience. Each interview lasted 45 min and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Nottingham Local Research Ethics Committee granted approval in January 2006.

Table 3 Interview schedule

Interviewer

The interviews were conducted by HP who is also a general practitioner (GP) partner at the practice. She undertook all the interviews and transcribed and analysed the data. Hence, the interviewer already had a relationship with the participants as their GP. It was necessary for her to be fully sensitive to the reflexivity; that is the way this pre-existing relationship would shape all aspects of the research process, in particular the interview itself.

Analysis

The method of analysis used an inductive approach to classify the data into categories and themes (Dey, Reference Dey1993). Each sentence or part sentence was scrutinized several times to understand the meaning, and what it represented. It was assigned a category, and gradually categories were reshaped into larger themes, or vice versa. There were no predefined ‘a priori’ categories or themes, they were inductively found from the transcripts. The strategy was to achieve conceptual clarification through classification, which was purposive, and guided by the overall research aims (Dey, Reference Dey1993). The analysis was carried out after each interview, comparing that interview to all the others, to find similarities, differences and new ideas. Connections and links were then sought between the themes and a template or map evolved, enabling a thematic analysis to be carried out (King, Reference King2004). The analysis was complete when a coherent story had been built by developing an account around the map, across all participants, using illustrative examples from each interview. Trustworthiness was demonstrated by using a second person to help analyse the transcripts and debate the importance and worth of the themes and categories. The WDREUG was consulted throughout the study from protocol development to analysis. Some WDREUG members independently read a sample of the anonymized transcripts, in order to debate and facilitate understanding of what represented the findings, and the meanings attributed to them. To improve the quality of this qualitative study, methods were recorded in detail, and criteria of reproducibility, reliability and trustworthy data analysis were applied (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Dingwall, Greatbach, Parker and Watson1998; Mays and Pope, Reference Mays and Pope2000). Nvivo 2 software (www.qrsinternational.com) was used to manage the data and store the text in an easily retrievable form.

Findings

Responses

The recruitment strategy was deemed unsuccessful. The necessity to opt in to the research process (in order to be available for consideration for recruitment), either by responding to a letter in English and returning a tear-off slip or by verbally replying to a poster advertisement, was not the best way of reaching people of different cultural backgrounds and the socially disadvantaged. By using targeted, personal, non-traditional recruitment methods (opportunistic verbal and telephone approaches by a known administrator), more hard-to-reach groups were willing to opt in.

Learning

Conditions for successful learning were at the heart of the findings. Although this was a heterogeneous group of people, there was a lot of similarity in their opinions and views.

Participant quotes are used to illustrate our findings and participant demographic identifiers are used with reference to those in Table 2.

Attitudes for learning

Learning about diabetes was very important and of great value. It was needed so that participants felt well and alive, lived a better life and the more of it the better. It was necessary for the learning to be personal, the desire had to come from inside. It was also about listening and being listened to, with your views taken seriously, in order to discern the choices and options for yourself.

‘Its good to hear when people talk, and sometimes them not talking to you, but your ears is there, can listen, you can listen, you can learn from it too, know what I mean?’

(M2)

The exception however was one who thought that he should only listen to the doctor.

Well it’s the doctors isn’t it, that’s it, it’s the doctor’s job to teach the patient when they come in to them. I mean as I’ve said, I’ve had good advice from your staff so I can’t really complain about it myself. And if other doctors don’t do that, there’s not much I can do about it, you know.’

(M1)

There was a great desire for quality in the learning experience, whoever delivered it: being treated with respect, being noticed and not ignored, the professional being interested in them, trust and competence in the teacher and the honesty of the process. For some, learning was recognised as an ongoing lifelong experience, of being in control, asking questions, keeping up to date and trying new things.

Ways of learning

Participants, who had all done some paid work, talked easily about how they had learnt about their jobs, including being shown the ropes by another person; three had been factory workers, others were a typist, caretaker, housing benefits officer, driving instructor and social worker. They expressed a sense of pride and positive self-esteem about their work. The interview schedule worked well in this regard. Talking about a familiar learning experience generated confidence in the articulation of opinions.

Family networks

The family played a big role as a source of learning and this was true of all participants. South Asian participants stressed how much they themselves knew; diabetes was common knowledge, attitudes to food and cooking, albeit not always healthy, continued down the generations. The Jamaican man had learnt from his aunty and wife. The white males had brothers with complications of diabetes, which influenced their determination to do better for themselves. The white female had nursed her own mother with diabetes for many years and had learnt from her.

The South Asian participants recognised the difficulty of getting their family members out of the home. The family had a duty to care for their elderly; they would be pitied if they were seen leaving the home to access learning, or indeed other types of social care.

(thinking of his own mother also with diabetes) ‘If you can get to the people around them, and then bring them from outside in, do you know what I mean? If they are not going to come to you as a nucleus, a central point, then maybe with everything else, they’ll come in.’

(M4)

The solution was felt to be active engagement with their family and friends, and to gather information and education into the home from outside.

Social networks

Informal networking was valued; it included meetings in pubs, church, place of work, own homes, out-patient waiting areas and two informal open sessions run at the GP practice designed to get people talking together about diabetes. There was specific bias here, as four of the participants had attended the sessions and been exposed to the author’s enthusiasm for education. One man who had attended both sessions did not like them, or value the group experience, but he was the exception.

But as for sitting in a …… I say I know I’ve come up to the two lots you’ve had…. That doesn’t seem to sit very well with me. I’ve come up because I would not be ignorant and not come up, I’ve come up to it, but uh! But as for, I say, talking to other people about it, no……… I mean it’s not you know whether I can go to people and talk to them, because they won’t make me feel any better.’

(M1)

But interestingly, he had already described changing his lifestyle after talking to a man at the pub who died from diabetes complications. For the rest, there was a lot of eagerness for listening and talking to others, for giving advice, for giving others a goal and setting an example. There was a common bond, it was ‘in built’, the desire to know how others with diabetes cope.

‘well I wouldn’t say it’s not their thing (informal meetings), because everybody’s having this diabetic or whatsoever it is. So what ever you from Africa or Jamaica or English or whatsoever it is, so long as you got it. And if you’ve got it, you got to take care of it, yeh.’

(M2)

The South Asian community felt more comfortable within their own groups; as it was difficult to get their women to leave the house, two or three might meet in their own homes.

All recognized the difficulty in reaching those people who chose to disregard their diabetes. Advertising, involving the community, exercise and social opportunities dedicated to those with diabetes, and linking up with other health campaigns like obesity or heart disease were identified as useful approaches.

‘if you hit the nail on the head really with people. If you just, sort of, get that bit that rings home, you know, that, well, you get them then’

(F4)

There was a need for diabetes to be noticed more, of it making a visual impact, including the importance of learning itself. Advertising posters, local radio and papers, a stall at the local market showing an educational video were all suggested. Temples, churches and mosques could be places for leaflets, short talks or films.

‘How many posters of burgers do you get? Big Macs! Do you know what I mean? You can go along and you see these posters of everything, but nothing, there’s nothing about (diabetes).’

(M4)

Learning delivered by the NHS

Most eventually did mention the role of the professional, GP practices, leaflets, books, the hospitals, occasionally Diabetes UK, in learning. The exception was one male who talked about it first. He had been ‘instructed’ by the practice nurse and ‘did what he was told’. Otherwise, health professionals were there to ask questions of, and to check out what others had said, but they could give conflicting advice. There were problems with leaflets, they could be confusing and contradictory, or they were only briefly read, or in the wrong language. Some felt videos and visual learning better than the written word.

‘Leaflets is not enough information or there’s too much information on what you should and shouldn’t do, there should be one for one and that’s it’

(M3)

Structured education

The attitudes towards a formal diabetes course were given by the tone, expression and body language of the participant and not always by the words spoken. This may have been part of the reflexivity, an influence of the interviewer’s dual role with regard to the participants. None had previously attended structured patient education for diabetes so their comments were not based on experience. Many barriers were voiced. One lady, whose own schooling had been disrupted, thought courses might be full of ‘academic types’ and too intimidating. A six-week course was considered too long, and particularly for the less-educated South Asians, the insight that the wife could not be more educated than the husband.

‘I mean, some people, because they can’t speak the language, thinking, oh their wife’s going out, bearing in mind they could be diabetes, or the man. They think, oh she may get above myself, and think it negatively.’

(F3)

Stress and depression as a barrier to learning

One participant described being very stressed and depressed; hence, it gave opportunity for the relationship between stress and depression, and successful learning to be explored. She had insight into depression stopping people from learning. Her close proximity to the negativity of the disease (seeing relatives die young from it) had led to a fear of diabetes, which diminished her capacity to change. All participants mentioned depression or stress at some point, particularly the need to guard against it.

‘If you want to do something, that’s not big problem, you can learn. But if you give up, or you can’t be bothered, or you don’t want to do anything, then you can’t learn’

(F1)

‘Like I said you know everything (about diabetes), you see everything but…. we talk about it. We talk about it, we do get scared, we do…. That’s another thing you know, we are not doing much about it. It’s just sitting on the sofas and just worrying and just thinking, Oh God what is going to happen! Why isn’t this happening, why? We are not solving anything but still, just sitting home and talking about it.’

(F1)

‘And you see other people worse than you, I mean like the diabetic foot clinic, people with amputations, and you know that while you’re there, you think, oh I’m lucky. But then when you’re in a quiet moment, in the middle of the night, you think, oh dear, could I end up like that?’

(F4)

Recognizing the link between their state of mind and their inability to act was also apparent.

‘I asked if that’s with the needle? I says, well I ain’t going to do it, and I can’t do it, and I won’t do it! Because I was that frightened, because I was so much afraid of the blood and injection’

(F2)

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

Summary of findings

Different recruitment methods were needed to engage hard-to-reach participants in discussing their attitudes and experiences of diabetes learning. The need to continue to learn about diabetes in different settings and contexts was strongly acknowledged by participants and, in its broadest sense, ongoing education was of great value. It needed to be a quality, ongoing, respectful experience involving listening and being listened to. The presence of stress and depression made it harder to engage in a learning experience and to motivate behaviour change. Past learning for employment was regarded positively and enabled discussion of learning issues through a familiar context. Past diabetes learning had been through family members, in informal social meetings and within consultations with health professionals, which were generally preferred to formal classes.

Strengths and limitations

This study has demonstrated that hard-to-reach participants from different cultural backgrounds hold very similar views regarding education quality, trustworthiness and the learning value of peers, as is held by white, mostly educated persons (Sturt et al., Reference Sturt, Hearnshaw, Barlow and Hainsworth2005b). Differences emerged according to the specific culture of the participant, in relation to where and how diabetes education can be accessed. In particular, some South Asians found it difficult to leave the home and preferred learning through informal family and social networks within the home, others were not always allowed to be educated.

However, it was a small study: only eight participants in total, who were interviewed once for 45 min, by a familiar GP. Reflexivity was a most important bias consideration in the study, as was the question of power relations (Rogers and Schwartz, Reference Rogers and Schwartz2002). The relationship had to aspire to change from one of doctor–patient, where the power was perceived to be with the doctor, to one of researcher–participant, where the relationship was equal and mutually enhancing. The problem is that primary care relationships are long term and create vulnerabilities; patients may feel less able to refuse to take part or to only give responses aiming to please the interviewer, based on the fear of compromising that relationship, or their own or family members’ future health care (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Murphy and Crosland1995). The author HP worked hard to negate the effects of reflexivity, by understanding it, explaining the changed relationship to participants, becoming a good interviewer gathering quality data, and being involved in the analysis and in interpretation of the findings. However, all interviews only provide access to what people say, not what they do (Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2004). The study confirmed the problems of opting in, namely, that it leads to low response rates, wasted resources and research of limited validity (Hewison and Haines, Reference Hewison and Haines2006). Invitation letters, information and posters were only provided in English. Non-English-speaking persons were not used for the additional recruitment and it further limited the diversity of participants, as did failure to recruit from other socially disadvantaged groups. In common with other studies, we found that altering the recruitment methods resulted in accessing people from the target population (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Sturt, Johnson, Mughal, Collins and Barnett2008). There was inevitably selection bias of those encouraged to opt in by personal invitation; those from black and ethnic minorities, who attended the practice regularly, were likely to agree and were around to be approached. Owing to these limitations, the sample being small and not representative of all the practice population, the findings are not generalisable to a wider setting.

Comparison with existing literature

Findings emerged that fitted with other findings about diabetes education in inner cities (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Collard and Begum2005; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Pound, Pancholi, Farooqi and Khunti2005). The need for the learning to be a quality respectful experience is found in other studies (Maillet et al., Reference Maillet, Melkus and Spollett1996; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Booth and Gill2003; Sturt et al., Reference Sturt, Hearnshaw, Barlow, Hainsworth and Whitlock2005a; Reference Sturt, Hearnshaw, Barlow and Hainsworth2005b). The preference for informal ways of learning, including the value of learning from others with the disease, is found in studies of other ethnic minorities (Maillet et al., Reference Maillet, Melkus and Spollett1996; Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Antone and Cornelius1999; Rosal et al., Reference Rosal, Goins, Carbone and Cortes2004; Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Collard and Begum2005). An increase in anxiety can be a negative effect of informal sharing (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Pound, Pancholi, Farooqi and Khunti2005). This downside emerged in this study with one participant’s experience of the diabetes foot clinic generating stress. Some South Asians value teaching from an ‘educated person’ (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Pound, Pancholi, Farooqi and Khunti2005). They express the views of the one exception in this study, ‘What will I learn from them (someone just with diabetes)?’ Even so, as with this study, there is limited motivation to attend a formal education programme. However, it could be argued that once a programme has been attended, attitudes become more positive and recruitment by word of mouth more successful.

The role of the family as a source of knowledge, support and influence, shaping attitudes to diabetes in general, not just education, is confirmed in other studies (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Barr, Edwards, Funnell, Fitzgerald and Wisdom1996; Reference Anderson, Goddard, Garcia, Guzman and Vazquez1998; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich1996; Maillet et al., Reference Maillet, Melkus and Spollett1996; Sadlier, Reference Sadlier2002; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Pound, Pancholi, Farooqi and Khunti2005). Participants in this study had a broad awareness from their family history, which seemed dominant in directing their learning, but it could be argued as stifling. Negative attitudes and too much information from previous generations could be unhelpful, distressful and lead to apathy.

The prevalence of increased levels of stress and depression in those with diabetes is well recognised (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Freedland, Clouse and Lustman2001; Grigsby et al., Reference Grigsby, Anderson, Freedland, Clouse and Lustman2002). In the wider education context, the inter-relationships between learning and health are enormously complex (Hammond, Reference Hammond2002). To become engaged in learning, a basic level of self-esteem is required (Aylward, Reference Aylward2002). Stress and depression, through low self-esteem, are barriers to learning; but improved self-esteem can also be an outcome of participation in a learning experience (James, Reference James2002). Hence, the challenge for the health professional is to foster that initial engagement. If the depressed person with diabetes can increase skills and confidence to self-manage through an educational experience, they may be able to reduce some of their stress levels, at least those related to living with diabetes.

Conclusions

• Diabetes education in different settings and contexts is greatly valued and important; it has to be a quality, respectful experience, involving listening and being listened to.

• The learning has to be personal, with the desire coming from within. It is an ongoing process of asking questions, keeping up to date and trying new things.

• The family plays a big role as a source and influence on learning.

• Being shown the ropes and meeting up informally with others are generally good learning experiences.

• Stress and depression are barriers to the engagement in learning, and can diminish capacity for change.

• Different types of recruitment strategies need to be considered for hard-to-reach groups.

Practice implications

Ongoing diabetes education for those with type 2 diabetes is not well developed. Although the findings from the study are not generalisable, they do show some transferability to the rest of those with type 2 diabetes registered at the practice. The reflective and insightful ideas of the participants can form a basis for future education opportunities within the practice.

To try and engage with more people with type 2 diabetes, it is planned to invite groups from the GP practice, to four informal sessions, based around talking to each other and their health professionals. Invitations will need to be varied, including personally, by telephone and in native languages. The emphasis for those running the sessions will be to provide the right conditions for successful learning so that it can be a quality, respectful experience, to help participants feel well, more alive and live a better life with diabetes. As well as diabetes itself, topics for discussion will include ways of learning, and perceived barriers and difficulties of meeting with their doctor or practice nurse in an unfamiliar way, such as a research or education setting. It would be a good opportunity for the further understanding of the successful engagement between the two parties and lead to an improved and confident dialogue between the patient and healthcare professional.

Funding

Research study supported by the general practice.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

Ms Helen Foster of Nottingham University and Warwick Diabetes Research & Education User Group helped with data analysis.