Introduction

The concept of altruism is evidenced in various disciplines, such as psychology, philosophy, economics, sociology, and evolutionary biology (Fehr and Fischbacher Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003; Sonne and Gash Reference Sonne and Gash2018). For these reasons, there are multiple definitions of altruism, of how it is achieved and can be observed. (Pfattheicher et al. Reference Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann2022). Overall, the concept of altruism is generally applied to any prosocial behavior carried out on a voluntary basis aiming to benefit the society or specific individuals (FitzPatrick Reference FitzPatrick2017; Pfattheicher et al. Reference Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann2022; Warneken and Tomasello Reference Warneken and Tomasello2009; West et al. Reference West, Griffin and Gardner2007). While altruism is primarily explained as an individual constitutive characteristic (DeYoung et al. Reference DeYoung, Quilty and Peterson2007), sources of motivations and the social norms underlying the exchanges between individuals are important dimensions to consider. Some potential sources of motivation include benevolence (Hubbard et al. Reference Hubbard, Harbaugh and Srivastava2016), empathy (Batson et al. Reference Batson, Batson and Slingsby1991), reward (Carlo and Randall Reference Carlo and Randall2002), anger (Fehr and Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2002; Mussweiler and Ockenfels Reference Mussweiler and Ockenfels2013), social norms, and interaction rules, such as social responsibility, group gain, and reciprocity (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zeng and Ma2020; Cropanzano and Mitchell Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005).

Patient altruism in end-of-life (EOL) settings

The expression of altruism has been understudied in EOL settings, which is of particular interest to better understand patients’ altruism. Patient positions at EOL are often reduced to a passive role, whereas the commitment of health-care professionals (HPs) and family caregivers around them receives more attention. However, literature from developmental psychology focusing on older adults broadens the understanding on altruism in this context. For example, they report more altruism by older people approaching the last phase of life than by younger people (Sparrow et al. Reference Sparrow, Swirsky and Kudus2021). This aligns with life span developmental theories showing a reorientation in motivation at EOL, often involving a sense of realization and meaning in life (Orenstein and Lewis Reference Orenstein and Lewis2021). Ebersole (Reference Ebersole, Wong and Fry1998) identified how the desire to help others is one of the most frequently mentioned aspects contributing to meaning in life. Similarly, Prager (Reference Prager2000) describes altruism as one of the most influential foundations of meaning in life. Sparrow and Spaniol (Reference Sparrow and Spaniol2018) showed that with increasing age, intrinsic values, such as authenticity, intimacy, spirituality, and altruism, are prioritized over extrinsic goals, such as achievement, competence, and power. There is also evidence showing shift toward meaningful social goals focusing on others, especially close ones, after the recognition that time is limited as we age (Carstensen et al. Reference Carstensen, Fung and Charles2003).

In the palliative care context, Fegg et al. (Reference Fegg, Wasner and Neudert2005) demonstrated how palliative care patients report higher self-transcendent values than healthy adults, a phenomena associated with altruism. Other research has shown that palliative care patients cite social dimensions as a source of meaning in life more than those in the general population (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, Berchtold and Strasser2020). While prosocial behavior and altruism can be explained from a developmental perspective, as detailed above, Vollhardt suggests that altruism may result from suffering after adverse life events, such as a life-threatening illness (Staub and Vollhardt Reference Staub and Vollhardt2008; Vollhardt Reference Vollhardt2009). In effect, patients may experience post-traumatic growth as a positive psychological change resulting from their struggle with life-threatening illness (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, Poncin and Althaus2022). In this perspective, altruism might be considered as a specific manifestation of post-traumatic growth in the palliative care context. These limited studies and findings point to the relevance and need to better understand patient altruism at the EOL settings.

One dimension of patients’ altruism at EOL has been thoroughly examined in literature and concerns their participation in research as an expression of altruism. Two systematic reviews evidenced how patients in palliative care understand participation in research as a gesture of giving back, providing support, and benefiting others (Gysels et al. Reference Gysels, Evans and Higginson2012; White and Hardy Reference White and Hardy2010).

The questions that guided our scoping review’s general aim were “What is the state of the scientific literature concerning the concept of ‘patient altruism’ in the context of EOL?” and more specifically “How do authors employ the concept of altruism?”; “How is altruism expressed?”; “What are the consequences of altruistic acts?”; and “What are the interventions that lead to altruism?.” To our knowledge, this is the first review addressing patient altruism in EOL settings.

Methods

We chose to do a scoping review given that it is the recommended methodology for exploring the breadth or extent of the literature, mapping and summarizing the evidence, and informing future research (Tricco et al. Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin2016). Scoping reviews are used to map key concepts within a field of research and to clarify working definitions and/or a topic’s conceptual boundaries (Arksey and O’Malley Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Munn et al. Reference Munn, Peters and Stern2018). They do not aim to assess instruments’ quality but rather to identify available evidence, ways of conducting research, and knowledge gaps in a given field (Munn et al. Reference Munn, Peters and Stern2018).

Eligibility criteria

According to recommendations, we combined a broad research question with a scope of inquiry that is clearly articulated (Levac et al. Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). We limited our search terms to relate to how altruism is interpreted and expressed by patients at the EOL.

Articles eligible to be included needed to (i) address the concept of altruism, (ii) involve patients in EOL, and (iii) be written in English, French, German, or Italian, major languages of the pertinent literature mastered by the authors. Reviewed articles could include original research, systematic literature reviews, editorials, discussion articles, and case reports and represent diverse methodologies. Posters and conference abstracts were excluded.

Articles were excluded from the review if they addressed altruism (i) manifested by HPs or relatives of palliative care patients; (ii) as part of volunteer activities or philanthropy such as donations or legacies after the death of the patient, for patients and HPs alike, (iii) in context of organ donation, (iv) as expressed through patient participation in research; (v) accomplished by cancer survivors; and (vi) that discuss altruism outside of EOL context.

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted in collaboration with a health information specialist (AT). The following bibliographic databases were searched on May 3, 2023: Embase.com, Medline ALL (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane CENTRAL (via the Cochrane Library), Web of Science Core Collection, Philosopher’s Index (EBSCO), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, and CareSearch Grey Literature Database.

The search strategies, translated for each source of information, combined free-text and index terms describing the concepts of altruism and EOL. No date or language limit was applied. The search strategies (supplementary online material – Table S1) were peer-reviewed by a biomedical information specialist.

For the concept of altruism, we used the following keywords: altruism, prosocial, social behavior, humanitarianism, selflessness, generosity, self-sacrifice, helping behavior, self-transcendence, universalism, benevolence, and unselfish.

For the setting, we used the following keywords: palliative, end of life, supportive care, comfort care, advanced or terminal or incurable disease/illness/sick/stage/patient/care/cancer/condition, life threatening, life limiting, hospice, and dying. International Standard Serial Numbers (ISSNs) of relevant palliative care journals were included in this concept, as seen in CareSearch’s PubMed filter (CareSearch 2021). The palliative care search filters developed by Rietjens et al. (Reference Rietjens, Bramer and Geijteman2019) were also used to identify relevant search terms.

Study selection

Records were retrieved from databases and exported into EndNote X20, and duplicates were removed (AT). In a first screening stage, irrelevant records were excluded (ACS). Then, 3 reviewers (ACS, MB, and a research assistant) independently and in parallel screened the same randomly selected 30 articles based on the abstract, discussed the results, and amended the exclusion/inclusion criteria before beginning screening for the articles to be included in the final review. A blind parallel review based on text was done for all the remaining articles. Each article (full text) was read by 2 reviewers (among the authors: ACS, GDB, MJD, CG, RJJ, PL, and MB) who compared via a discussion their final evaluations. Disagreements were discussed and resolved among 2 reviewers (ACS and MB).

Data charting process and synthesis

The scoping review is reported using the PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews (Tricco et al. Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin2018).

We organized the summary of the state of scientific literature (Arksey and O’Malley Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) according to basic descriptive statistics on the nature and distribution of the studies included in the review. Following team discussions, 2 authors (ACS and MB) developed a deductive data charting form that was used to deductively extract data from the selected articles. This form was used to create a data extraction sheet in Excel. Data were extracted on authors, publication title, journal, year of publication, country of the study (for research studies), type of article, design, settings, sample, and study aims. Then, findings were organized according to specific information about the articles that explored altruism, how altruism is used in the article and the method that was used to identify or explore altruism. Second, the literature was organized thematically; themes were created to correspond to the objectives of the study. The main themes and sub-themes include (theme 1) how authors employ the concept of altruism, including 3 sub-dimensions (i) how authors conceptualize altruism, (ii) how they define it, and (iii) what theoretical frame, if any, they use; (theme 2) how altruism is expressed; (theme 3) the consequences of altruistic acts; and (theme 4) possible interventions leading to patient altruism at EOL.

Results

Search flow and study characteristics

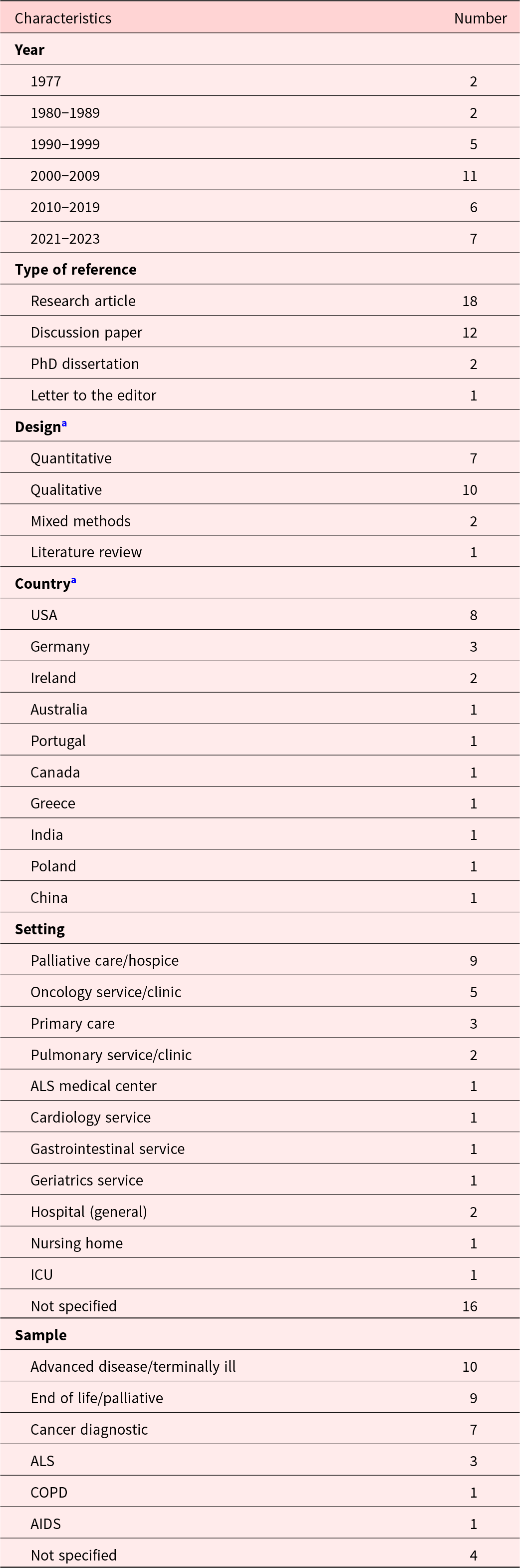

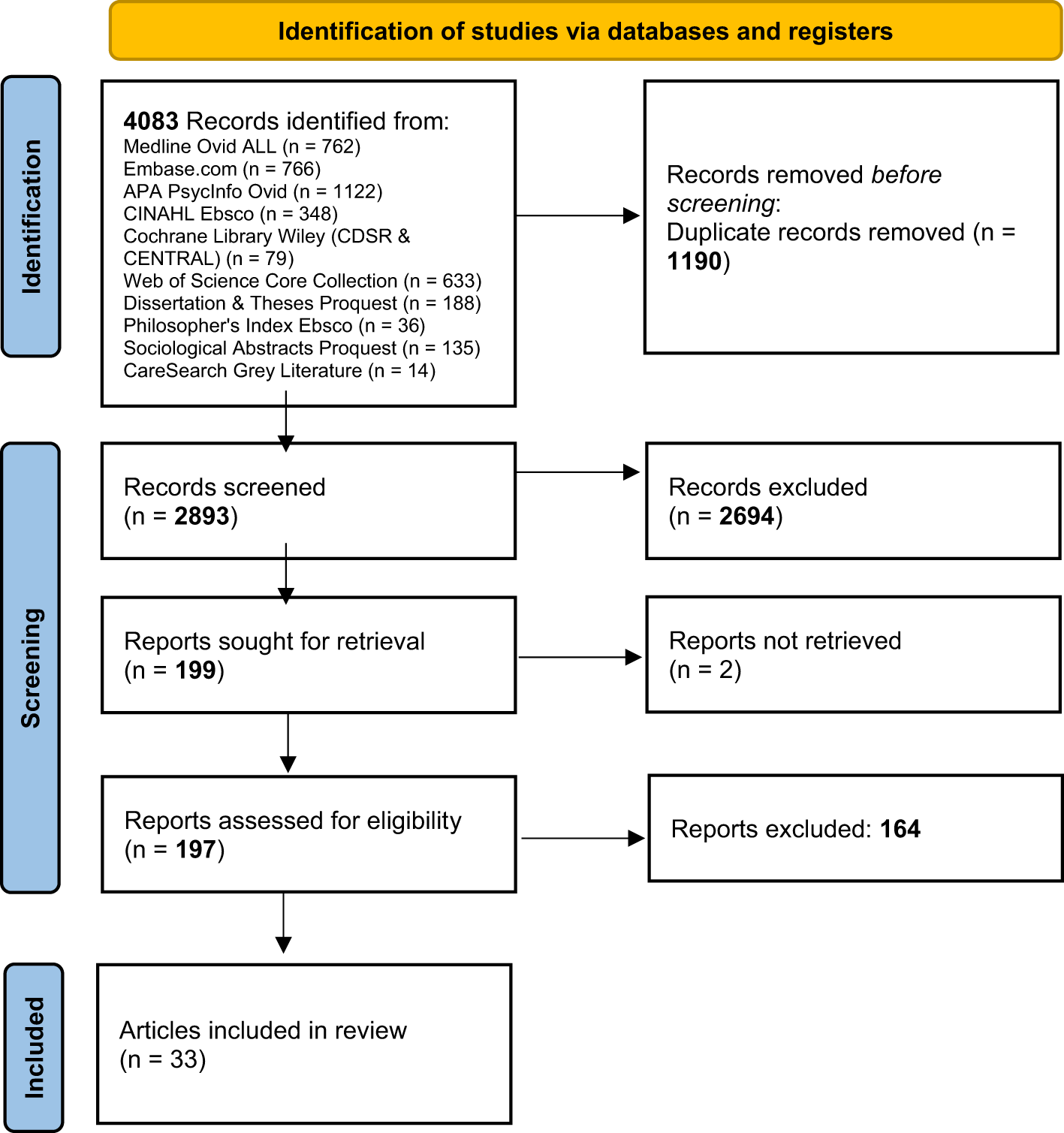

The search identified 2893 records after duplicates were removed. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 199 articles were identified after an initial evaluation according to title and abstract. There were evaluated by pairs of reviewers, and 33 articles were retained for the final analysis (Table 1). The study selection process is described in Figure 2 (Page et al. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt2021).

Table 1. Article characteristics

a For scientific articles (research articles and PhD dissertations).

Most articles were published between 2000 and 2009 (n = 11), concerned original research (n = 20, combining articles and PhD dissertations); research studies were predominantly conducted in the US (n = 8) and concerned palliative care (n = 9).

We then extracted data about how altruism is used in the article and the methods used to identify or measure it (supplementary online material – Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

In most articles (n = 24), altruism was used to explain or describe other phenomena of interest, meaning that it was not the main focus of the article but was evoked to interpret results. In 7 of them, altruism was the main focus of the article. In 2 articles, altruism was used as contextual background information but was not mentioned in relation to the results.

In terms of methods for measuring altruism, 12 articles used a qualitative methodology, 6 employed quantitative methods, and 1 was a literature review (Vachon et al. Reference Vachon, Fillion and Achille2009). Eight questionnaires were applied: the Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Brandstatter and Kramer2010, Reference Fegg, Kramer and L’Hoste2008); the NEO Personality Inventory Revised (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007); the Anticipated Farewell to Existence Questionnaire (Valdes-Stauber et al. Reference Valdes-Stauber, Stabenow and Bottinger2021); a non-validated questionnaire evaluating experience of support group by assessing 5 therapeutic factors (Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009); the Quality of Life Questionnaire (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021); the Scale of Spiritual Transcendence (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021); the Purpose in Life Questionnaire (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021); and the Altruism Scale (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021).

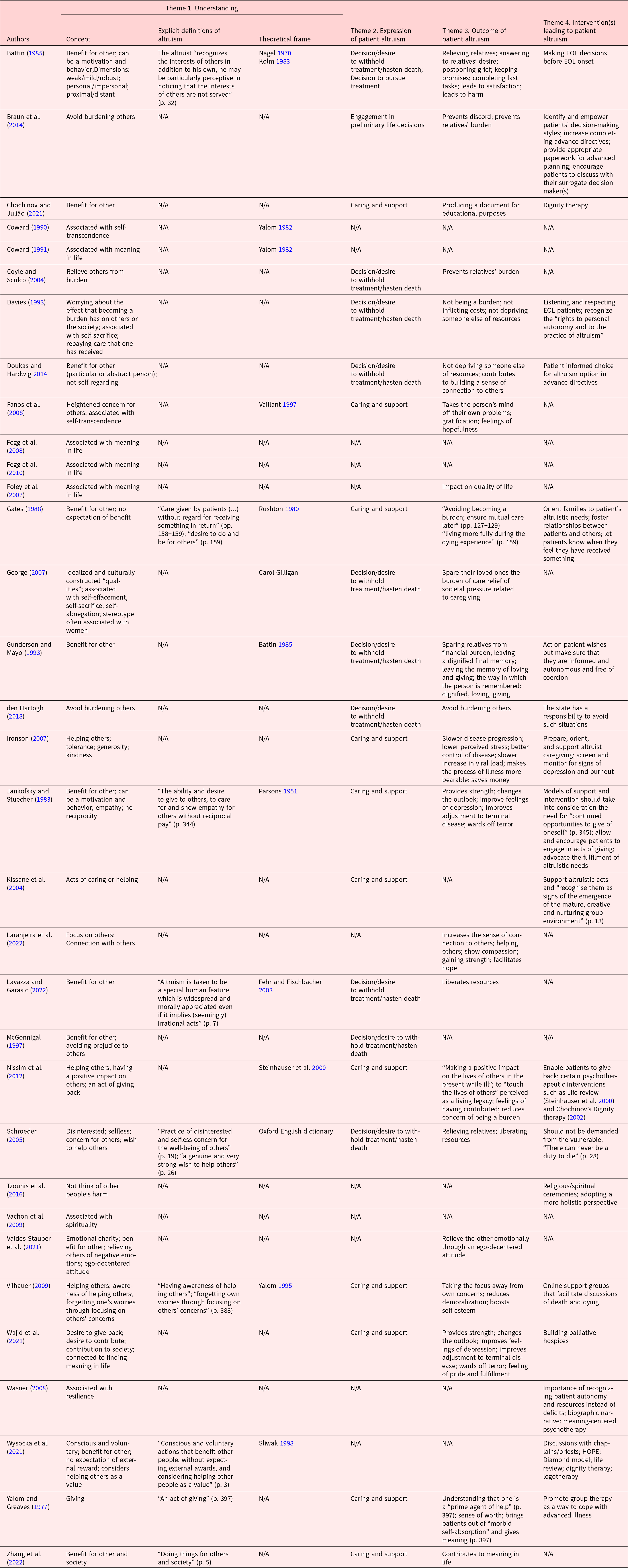

Findings were summarized according to 4 themes that were derived deductively and correspond to our research questions (see Table 2): (i) how authors employ the concept of altruism (including 3 sub-themes: a description of how authors explain/employ patient altruism as a concept, any definition quotes, and the theoretical frame); (ii) how altruism is expressed, (iii) the consequences of altruism, and (iv) possible interventions leading to patient altruism in EOL and palliative care settings.

Table 2. Themes

Theme 1. Understandings of altruism

Within this theme, we considered how authors understood (i.e., defined, described, or conceptualized) patient altruism as being (i) a concern for others, (ii) a wish and an act at the same time, or (iii) a dimension of another phenomenon. An explicit definition of what altruism means was found in 9 articles. In 13 of them, a theoretical frame or article for the conceptualization of patient altruism was provided.

Sub-theme (i), Altruism as a concern for others

In 27 articles, altruism was described as oriented toward others. According to 11 articles, altruism was oriented toward the recipients’ benefit (Battin Reference Battin1985; Chochinov and Julião Reference Chochinov and Julião2021; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Gates Reference Gates1988; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Lavazza and Garasic Reference Lavazza and Garasic2022; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997; Valdes-Stauber et al. Reference Valdes-Stauber, Stabenow and Bottinger2021; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhang and Yang2022). Seven emphasized that altruism was a way to express concern (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Schroeder Reference Schroeder, Häyry, Takala and Herissone-Kelly2005; Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021) and/or to avoid or relieve burden for others (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Beyth and Ford2014; Coyle and Sculco Reference Coyle and Sculco2004; Davies Reference Davies1993; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018). Other understandings of altruism encompass avoiding prejudice to others (McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997), providing help and care (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Schroeder Reference Schroeder, Häyry, Takala and Herissone-Kelly2005; Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021), and not wishing harm (Tzounis et al. Reference Tzounis, Kerenidi and Daniil2016).

Six articles addressed reciprocal dimensions of altruism. In 3, altruism was considered as reciprocity toward someone who has previously been of assistance (Davies Reference Davies1993; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021) and in the remaining 3, it was associated with not expecting any reciprocity from the recipient (Gates Reference Gates1988; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021).

Sub-theme (ii), Altruism as a wish and an act

Four articles (Battin Reference Battin1985; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Schroeder Reference Schroeder, Häyry, Takala and Herissone-Kelly2005; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021) distinguished between altruism being present in ideas, either as a wish, desire, or motivation, and altruism that manifests through action.

Sub-theme (iii), Altruism as a dimension

In 10 articles, altruism was considered as a dimension associated with other concepts such as self-transcendence (Coward Reference Coward1990, Reference Coward1991; Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008), meaning in life (Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Brandstatter and Kramer2010, Reference Fegg, Kramer and L’Hoste2008; Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021), self-sacrifice (Davies Reference Davies1993; George Reference George2007), and patient resilience in the context of incurable disease (Wasner Reference Wasner2008).

Theme 2. Expressions of altruism

The second theme concerned how patients express altruism at the EOL. Within this theme, we mapped 4 sub-themes: (i) care and support for others; (ii) desires and decisions to withhold treatment and hasten death; (iii) desires and decisions to prolong life; and (iv) engaging in EOL decision-making. Information about this was missing in 11 articles.

Sub-theme (i), Altruism as care and support

In 33% of the reviewed articles (n = 11), the authors identified patients expressing altruism at the EOL through acts of care and support toward others. The majority (n = 9) of these acts were oriented toward other patients. For example, caregiving (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007), transporting other patients to group sessions (Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004), providing meals for sick group members (Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004), expressing concern for other patients’ relatives (Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004), remembering other group members’ medical appointments and test dates (Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004), sharing symptoms and coping experiences (Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021; Yalom and Greaves Reference Yalom and Greaves1977), telephoning or visiting group members (Yalom and Greaves Reference Yalom and Greaves1977), and sharing life stories as a means to motivate and inspire others with similar problems (Chochinov and Julião Reference Chochinov and Julião2021; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2004; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhang and Yang2022). Of these, 3 articles equally considered altruism in pure thoughts, i.e., desires and intentions to be altruistic, even when they were not fully realized acts (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021).

Two articles described patient altruism expressed through acts of care for HPs (Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021; Yalom and Greaves Reference Yalom and Greaves1977), such as aid with writing medical records and the willingness to share their own experiences as patients for teaching purposes. One article designated altruism as acts of care for relatives, with patients at the EOL serving as life models and desensitizing people about death (Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012).

Subtheme (ii), Altruism as desires and decisions to withhold treatment or actively hasten death

According to 10 articles, patients expressed altruism through desires or decisions to withhold treatment or even actively hasten death. Five articles considered altruism displayed by requests to limit or refuse life-prolonging treatments (Battin Reference Battin1985; Coyle and Sculco Reference Coyle and Sculco2004; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Lavazza and Garasic Reference Lavazza and Garasic2022). Five others described altruism expressed through patient requests to physician-assisted suicide (Davies Reference Davies1993; George Reference George2007; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997; Schroeder Reference Schroeder, Häyry, Takala and Herissone-Kelly2005).

Sub-theme (iii), Desires and decisions to prolong life

In 1 article, patients’ decisions to pursue treatment with the intention of prolonging life were considered as altruistic for the benefit of relatives (Battin Reference Battin1985).

Sub-theme (iv), Engagement in preliminary EOL decisions

One article considered the act of patients engaging in advance care planning, e.g., completing advance directives and discussing EOL issues, as being generated by altruistic motives, to avoid burdening their relatives with decision-making and to prevent discord (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Beyth and Ford2014).

Theme 3. Consequences of altruism

Information about the consequences of patient altruism was present in 26 articles. When discussing consequences, we refer to the intended and actual results of altruistic acts from patients. We distinguished between (i) positive patient-centered consequences, (ii) positive non-patient centered consequences, and (iii) negative consequences.

Sub-theme (i), positive patient-centered consequences

Positive patient-centered consequences were mentioned in 14 articles. Patient altruism contributes to meaning in life (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhang and Yang2022) and leads to improving patient sense of satisfaction, pride, and gratification (Battin Reference Battin1985; Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Yalom and Greaves Reference Yalom and Greaves1977), to feelings of hopefulness (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008), to building a sense of connection with others (Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Laranjeira et al. Reference Laranjeira, Dixe and Semeao2022), and to leaving a dignified memory of oneself (Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993). Altruism was also found to improve patient quality of life (Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007), by inducing slower disease progression (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007), lower stress (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007), a sense of better control over the illness and by changing the outlook that people have on their illness (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Laranjeira et al. Reference Laranjeira, Dixe and Semeao2022; Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021), by alleviating fears associated with death (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021), and by reducing feelings of depression (Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Vilhauer Reference Vilhauer2009; Wajid et al. Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021). It was also considered as an adaptive resource for coping with terminal disease and death (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983).

Sub-theme (ii), Non-patient-centered consequences

While describing the recipients of altruistic acts, 4 important categories were referred to (i) relatives, (ii) HPs, (iii) individuals suffering from the same condition, and (iv) generic others. Three articles mention the contribution that altruistic acts bring to recipients and/or to society and how it manifests itself. For example, patients might transform their stories into educational resources (Chochinov and Julião Reference Chochinov and Julião2021) and have a positive impact on close ones’ memories of the deceased person (Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993). Ironson (Reference Ironson and Post2007) notes that altruistic acts can be cost-effective and save society money through patients’ wish to die to liberate resources.

Sub-theme (iii), Negative consequences

Two articles mention negative consequences of patient altruism. Altruistic acts can generate harm for both altruistic agents and their intended beneficiaries (Battin Reference Battin1985; Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007). For example, individuals may misjudge potential benefits to others and might impose well-intentioned but ill-received, burdensome consequences, particularly when decisions to limit life are involved. Altruist acts might also be expressed by individuals with low self-respect, who consider themselves valueless, and feel that their life is not worth extending.

Theme 4. Interventions

Interventions by HPs and relatives to encourage patient altruism at the EOL are mentioned in 19 articles. We categorized these types of interventions into the following sub-themes: (i) planning for future care; (ii) specific interventions; (iii) creating opportunities for patients to engage in planning for future care; and (iv) enabling and encouraging patient altruism.

Sub-theme (i), Planning for future care

Three articles underline the direct link between patients’ engagement in advance care planning and altruistic decisions (Battin Reference Battin1985; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Beyth and Ford2014; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014). As such, creating more opportunities for such discussions and decisions, even before EOL, was identified as a way of encouraging patient altruism.

Sub-theme (ii), Specific interventions

Eight articles discuss specific interventions that would encourage altruistic acts, such as Dignity Therapy (Chochinov and Julião Reference Chochinov and Julião2021; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021), the Life Review (Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021) and biographic-narrative discussions (Wasner Reference Wasner2008), HOPE (H—sources of hope, strength, comfort, meaning, peace, love and connection; O—the role of organized religion for the patient; P—personal spirituality and practices; E—effects on medical care and end-of-life decisions) (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021), Diamond model (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021), meaning-centered psychotherapy (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021), and logotherapy (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021). Less specific interventions consist of HPs engaging in discussing issues of death with patients, by involving mediators or events, such as chaplains, priests, or religious ceremonies (Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021) or through support groups and group therapy (Tzounis et al. Reference Tzounis, Kerenidi and Daniil2016; Wysocka et al. Reference Wysocka, Wawrzyniak and Jarosz2021). For Wajid et al. (Reference Wajid, Rajkumar and Romate2021), increasing the offer of palliative care would lead to patients being more altruistic in response to the care received.

Sub-theme (iii), Enabling and encouraging patient altruism

Six articles argue that HPs should also allow and encourage patients to be altruistic whenever possible (Davies Reference Davies1993; Gates Reference Gates1988; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983; Nissim et al. Reference Nissim, Rennie and Fleming2012; Wasner Reference Wasner2008). This involves listening and respecting altruistic needs (Davies Reference Davies1993; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993), informing relatives of the benefit of such acts and fostering close relationships (Gates Reference Gates1988), and expressing gratitude toward patients (Gates Reference Gates1988). Wasner (Reference Wasner2008) underlines the importance of HPs recognizing patient autonomy and patient resources, among which altruism, instead of deficits.

Sub-theme (iv), Not encouraging altruism

Six articles raise a need for caution about always actively encouraging altruistic acts, particularly when such acts may lead to patient decisions around withdrawing or refusing care. Two refer specifically to the fact that certain acts that might be conceived as altruistic by patients, such as refusing life-prolonging care, might be experienced as burdensome and stressful for relatives who are the intended benefits of the act (Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997). Two articles warn against the instrumentalization of altruism in EOL contexts by means of interventions, which might manipulate the goodwill of certain people (Battin Reference Battin1985; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018). Four articles discuss the important role that HPs have in ensuring that altruistic acts leading to decisions of withdrawing or refusing life-prolonging care are informed, voluntary, and autonomous (Battin Reference Battin1985; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993), and in monitoring patients for signs of depression, burnout, and factors that might be related to lower feelings of self-worth (Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007).

Discussion

This scoping review synthesizes the empirical literature on patient altruism in EOL contexts, particularly with regard to how the concept of altruism is understood and used by researchers and clinicians, how patients express altruism, the consequences of altruistic gestures, and interventions to encourage altruism.

We found that altruism is rarely defined explicitly and that authors often draw on what is considered as a common understanding. This observation was also made in a recent review of concepts and definitions related to altruism (Pfattheicher et al. Reference Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann2022). When looking at the understanding of altruism, we highlighted that altruism may be understood as an intention and an act at the same time. This is an important distinction when considering EOL context. Patients at EOL are confronted with questions brought on by diminished capacities and imminent death. This particular stage of the life course may bring people to reflect differently about their relationships, especially insofar as how they express altruism. Limited physical, emotional, or cognitive abilities may limit these patients’ expressions of altruism and constrain them by only enabling them to express altruism as intentions or wishes, which can lead to frustration.

We additionally found that altruism is not usually the main focus in the reviewed articles but often an explanatory element used in the interpretation of the results. In 8 studies, altruism is presented as a sub-dimension of another concept related to patient’s experience of EOL, such as self-transcendence, meaning in life, self-sacrifice, and resilience. The scoping review exercise showed that the range of instruments used to measure and evaluate altruism is varied. We identified both qualitative and quantitative approaches, though no standardized approach.

We identified a wide range of altruistic expressions, ranging from practical acts of care to unrealized desires to generate welfare in others. An important body of the literature focused on engaging in advance care decisions aimed at prolonging or limiting life (Battin Reference Battin1985; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Beyth and Ford2014; Coyle and Sculco Reference Coyle and Sculco2004; Davies Reference Davies1993; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; George Reference George2007; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Lavazza and Garasic Reference Lavazza and Garasic2022; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997; Schroeder Reference Schroeder, Häyry, Takala and Herissone-Kelly2005). Articles repeatedly associate such decisions, in this context, to a desire to relieve relatives of the burden of care (practical and emotional) or to contribute to a redistribution of resources toward others who might benefit more from them. This shows that individuals in EOL contexts are preoccupied with concerns that their care has beyond their benefit and that their altruism addresses inequities that they feel they might have engendered. Some authors were more critical toward enabling and supporting such altruistic expressions and highlight their ethical implications, notably that such decisions might be made under coercion or under the influence of factors such as depression in life (Battin Reference Battin1985; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997).

In terms of consequences of patient altruism at the EOL, we distinguished between patient-centered and non-patient-centered consequences. This distinction reflects an ongoing discussion in the literature, which opposes pure and selfish altruism (Feigin et al. Reference Feigin, Owens and Goodyear-Smith2014). The former is characterized by an ultimately egoistic motivation and the latter refers to the ultimate goal of increasing the welfare of other people. In this case, self-reward would only be a secondary effect or a by-product of the first goal.

Regarding non-patient-centered consequences, the distinction between relatives, HPs, individuals suffering from the same condition, and generic others showed that important “others” toward whom patients might feel a desire to display altruism concern not only those closest to them (relatives and HPs) but also those with whom they identify in more universal terms, such as other people in the same condition or with society as a whole. While altruism toward closest others may be brought about due to a sense of individual interest (for example, reciprocity or responsibility), altruism toward distant others demonstrates how people, even at the end of their lives, may maintain an awareness of the larger context and can continue to feel a sense of belonging.

Reflecting patient-centered consequences, articles identified a direct impact on the benefactor’s meaning of life and feelings of worthiness but also an improvement of their quality of life and satisfaction. This indicates that the EOL context may be conducive to altruism and highlights the important value of encouraging patients to express altruism and enabling them opportunities to do so. However, societal conceptions and expectations about patients at EOL, in particular the tendency to bypass patient autonomy, might preclude them from acting on such desires (Battin Reference Battin1985; Jankofsky and Stuecher Reference Jankofsky and Stuecher1983). In light of this, a majority of the reviewed literature acknowledges altruism as an important quality and resource that should be recognized and facilitated by relatives, close ones, and HPs. Many authors underline the need for HPs to recognize the altruistic need that patients have, to respect them and advocate for them. Since one of the specificities of altruistic decisions at EOL entails consideration about prolonging life or not, one such intervention is providing opportunities and supporting individuals to engage in making these kind of decisions while they still have the cognitive capacity to do so, notably when planning and discussing future (Battin Reference Battin1985; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Beyth and Ford2014; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014).

This scoping review provides several potentially relevant directions for future research on patient altruism at the EOL. There is a need to refine our understanding of this concept, both in research efforts as well as in clinical practice. This is particularly relevant for altruistic decisions concerning the withholding of life-prolonging interventions or those about hastening death, which have important implications also from a societal, political, and ethical point of view. For some (Battin Reference Battin1985; den Hartogh Reference den Hartogh2018; Doukas and Hardwig Reference Doukas and Hardwig2014; Gunderson and Mayo Reference Gunderson and Mayo1993; Ironson Reference Ironson and Post2007; McGonnigal Reference McGonnigal1997), the reviewed literature focused mainly on the positive consequences of altruism. This suggests that this concept benefits from high societal value and that more research is needed to explore the possible negative positive implications of certain altruistic acts. Overall, our results underscore the recommendations put forth by Pfattheicher et al. (Reference Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann2022) and highlight the need for authors to define and reflect on how they conceptualize their understanding of patient altruism.

Limitations

Our scoping review has some limitations. Scoping reviews do not appraise the quality of evidence, nor do they generate significant quantities of data, given that research questions are broad, exploratory, and conceptual in nature (Arksey and O’Malley Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). Our research strategy also presents some limitations. Complementary search methods, such as using Google Scholar to retrieve references in which altruism was only mentioned in the full text or applying citation searching techniques to the included articles, might have allowed us to identify additional articles.

Conclusion

This scoping review illustrates the importance that altruistic acts and intentions have for patients in EOL contexts. Patient altruism is associated with better quality of life and higher meaning in life. Expressions of altruism range from practical acts of care to unrealized desires to generate welfare in others. Our findings suggest that a particular behavior conceived as altruistic by patients and that is specific to the context of EOL is the decisions to engage in advance care planning aimed at prolonging or limiting life. Current understandings and explanations of altruistic behavior from patients at the EOL are relatively scarce and may benefit from further investigations that have a more rigorous and explicit approach as to how the notion of altruism is conceptualized.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951524000361.

Acknowledgments

We thank our research assistant, Fidelia Pittet, for her support with the review.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.