Highlights

What is already known

Mapping reviews are systematic methods designed to identify research status and gaps to reduce resource wastage.

Their use is increasing, especially in health and social sciences, but inconsistencies in concepts and reporting standards exist among different organizations and authors.

What is new

This study systematically analyzed existing guidance and methodological studies to elucidate and propose a consistent framework for terminologies, definitions, categorizations, timelines, and comparisons with other review methods.

It identified 28 reporting items for mapping reviews, providing a comprehensive set of evidence-based reporting recommendations.

Potential impact for Research Synthesis Methods readers

The proposed framework and reporting items aim to bridge existing gaps and provide essential methodological and reporting resources for primary authors, reviewers, journal editors, and other stakeholders.

These recommendations will serve as a foundation for future methodological researchers, guideline developers, and practical researchers, promoting complete and transparent reporting in mapping reviews.

1 Introduction

In response to the crucial challenge of optimizing the allocation of available resources to areas with the highest potential impact and minimizing research waste, researchers and policymakers urgently require a systematic and efficient approach to identify research gaps, needs, and priorities, as well as to enhance access to high-quality evidence for decision-makers.Reference Grainger, Bolam and Stewart 1 – Reference Wong, Maher and Motala 3 Mapping reviews (MRs) represent a method of evidence synthesis that systematically collects, assesses, and synthesizes existing evidence to clarify the current state and gaps in research, thereby fostering further research and decision-making.Reference Grant and Booth 4 Introduced by the Yale Prevention Research Center in 2000 as “evidence mapping,”Reference Katz, A-l and Girard 5 several organizations including the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Center), the Global Evidence Mapping Initiative (GEMI) in Australia, the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE), the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), and the Campbell Collaboration have since developed specific evidence products based on this method.Reference Saran and White 6 , Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 These products systematically organize and present current evidence and gaps within specific fields, providing valuable information for future research initiatives. Additionally, numerous institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) have employed the MR approach.Reference Hempel, Taylor and Marshall 8 – 11

Research findings have indicated a significant increase in the application of MRs since 2017, with these maps becoming increasingly prevalent in various fields such as medicine, environmental science, international development, and other health and social sciences.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 , Reference Li, Li and Li 12 – Reference Chew, Whitelaw and Vaduganathan 15 However, the absence of universally accepted reporting standards and methodological guidance has led to varied terminologies and reporting formats across different organizations and research fields, despite their shared objectives.Reference Saran and White 6 This lack of consistency in core methodological concepts and reporting has substantially impeded the development of high-quality MRs and curtailed their potential to reduce research waste. In recent years, several guidance documents aimed at standardizing this method have been published. Noteworthy among them are the guidance by Howard White et al. for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map in social sciences,Reference White, Albers and Gaarder 16 the ROSES (RepOrting standards for Systematic maps) by Neal R. Haddaway et al. for environmental sciences,Reference Haddaway, Macura and Whaley 17 and the guidance for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering by Kai Petersen et al.Reference Petersen, Vakkalanka and Kuzniarz 18 Furthermore, a methodological study by Hanan Khalil et al. in 2023 has underscored the existing methodological inconsistencies and confusion in the field.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 Developing a widely accepted conceptual framework and reporting recommendations that encapsulate the unique functionalities of MRs, based on existing guidance and methodological studies from various organizations and fields, represents a critical direction for future research.

This study follows the established methods for a scoping review as defined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI).Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco 19 Its aims are to elucidate and propose a consistent framework for key concepts and collect appropriate reporting items based on existing guidance and methodological studies related to MRs.

2 Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews reporting guideline.Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin 20 The protocol for this study has been published elsewhere.Reference Li, Ghogomu and Gaarder 21

2.1 Literature search

In the initial stage, nine electronic databases (Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, the Campbell Library, Web of Science Core Collection, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, VIP Chinese Science and Technique Journals Database, the Chinese Biomedical Database, Wan Fang Data) and 11 institution websites (Supplement Table S1) were searched from inception to January 2024 to ascertain the best available evidence. Following this, backward citation searching was performed for references cited in both primary studies and reviews related to the topic identified during the initial search. Furthermore, we consulted content experts in the field, particularly those on the advisory board, to further augment our resources. Simultaneously, the search strategy was determined based on the search terms, with no restrictions on date, language, or country/region. The major search terms and strategies (see Supplement Table S1) included the following: “evidence map*” or “gap map*” or “evidence gap*” or “systematic map*” or “evaluation map*” or “descriptive map*” or Megamap or Mega-map or “map of map*” or “mapping evidence” or “mapping review*.”

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

According to JBI guidance, the inclusion criteria were formulated using the “PCC” framework, which encompasses Population, Concept, and Context.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 , Reference Pollock, Peters and Khalil 22 In this study, population and context were deliberately omitted, implying an absence of specific restrictions, while the Concept included any guidance documents and methodological studies pertinent to MRs.

While formal guidance documents typically undergo a structured development process, similar to approaches adopted by other study,Reference Movsisyan, Arnold and Evans 23 this project did not confine the review scope exclusively to papers that delineate a formal guidance development process. Instead, we aimed to encompass a broad range of perspectives by including all guidance documents, whether published in journals or not, that offer advice and specific recommendations on key concepts, steps, principles, and strategies of MRs.Reference White, Albers and Gaarder 16 , Reference Khalil and Tricco 24 , Reference Campbell, Tricco and Munn 25

We included any methodological study that describes or analyzes methods in published or unpublished MRs.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 , Reference Miake-Lye, Hempel and Shanman 26 Methodological studies employ systematic methods to analyze literature gathered through systematic search techniques, often using a research report as the unit of analysis.Reference Mbuagbaw, Lawson and Puljak 27 An example of an eligible methodological study is a recent scoping review of 335 MRs by Khalil et al.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7

We excluded duplicate literature and individual MRs.

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

The entire process of screening and data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers. When discrepancies arose between the reviewers, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve the differences. Before the formal screening, we conducted training and a pilot study on approximately 10% of the search results to ensure that both reviewers achieved a minimum 90% agreement level. We utilized Covidence (www.covidence.org) for literature screening. Initially, duplicate studies were identified and removed. Subsequently, two reviewers evaluated the titles and abstracts of the selected studies. Studies were removed from further review if both reviewers agreed to exclude them. If at least one reviewer included a study, or if the title and abstract provided insufficient information for a decision, the full article was obtained for further review.

A standardized data extraction form was developed specifically for extracting the desired information, utilizing Excel 2023 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Following a pilot test of the data extraction form, teams of two reviewers independently extracted data, including descriptive information such as publication author, year, title, and country; research field, including health, social sciences: aging, business and management, children and young persons’ well-being, climate solutions, crime and justice, disability, education, international development, knowledge translation and implementation, and social welfare based on the classification standard of the Campbell Collaboration, and othersReference Iqbal, Khan and Niazi 28 – Reference Yang 31 ; key concepts of MRs, including employed terminology, definition, and category; and reporting characteristics including, but not limited to, the items related to titles, authors, abstracts, background, methods, results, conclusions, and funding.

2.4 Data analysis

We presented the results using tables and figures. Descriptive summary statistics, including frequency and median (interquartile range [IQR]), were calculated for each specified potential reporting item. Additionally, we adopted a narrative approach in cases where quantitative synthesis was not feasible. Our reporting adhered to the PRISMA for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin 20

2.5 Role of the funding source

The sponsors were not involved in research design, data collection, data analysis, and report writing. The corresponding author is responsible for all aspects of the study to ensure the proper investigation and resolution of the research for problems related to accuracy or completeness. The final version was approved by all authors.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

Figure 1 presents a flowchart depicting the literature selection process. Initially, 28,886 relevant records were identified. Of these, 11,746 records were removed due to duplication. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 17,140 studies were then screened, resulting in 16,995 being excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 145 articles were further assessed for eligibility, leading to the exclusion of an additional 77 studies, detailed in Supplement Table S2. Ultimately, 68 documents met our eligibility criteria and were included in the scoping review.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the literature screening process and results.

3.2 Study characteristics

As illustrated in Table 1, a total of 68 documents were included in the scoping review, comprising 59 guidance and 9 methodological studies, predominantly journal articles (56, 82.35%). The UK contributed the most documents (24, 35.29%), followed by the USA (13, 19.12%), with Australia and China each contributing five documents (7.35%). There has been a rapid increase in the number of relevant documents over time, particularly from 2018 to 2023, during which more than 30 documents were identified. The majority of documents focused on health science (13, 19.12%) and climate solutions/environmental sciences (12, 17.65%), with 24 documents (35.29%) not specifying a research field.

Table 1 Characteristics of included documents

Note: NR, not reported indicates that there are no restrictions on the research field for entries in this table.

3.3 Frequency and field distribution of terminology

As indicated in Table 2 and the Supplement Table S3, the included studies mentioned 24 research terms related to MRs. The term “evidence map” was the most frequently used, appearing in 23 documents and accounting for 33.82% of all included documents. This was followed by “evidence mapping” (19, 27.94%), “systematic map” (17, 25%), “evidence and gap map” (15, 22.06%), and “mapping review” (7, 10.29%). Regarding the timeline of term usage, “evidence mapping” and “evidence map” appeared earliest,Reference Katz, A-l and Girard 5 while “mapping review/systematic map” was categorized as one of the 14 review types in a study published by Maria J. Grant et al. in 2009.Reference Grant and Booth 4 The terms “mapping review” and “evidence gap map” were adopted in guidance and methodological studies most recently published in 2023.

Table 2 Terminologies used in included documents and corresponding research fields

Note: NR, not reported indicates that there are no restrictions on the research field for entries in this table.

Regarding the distribution of research fields (Table 2), documents using the terms “evidence map” and “evidence mapping” primarily focus on health sciences (11, 47.83%; and 10, 52.63%, respectively) and often do not specify a research field (8, 34.78%; and 6, 31.58%, respectively). Documents utilizing “evidence and gap map” typically address social sciences such as education and climate solutions (7, 46.67%). Those labeled as “systematic map/mapping,” “systematic evidence map/mapping,” and “evidence review map/mapping” predominantly target climate solutions in environmental sciences (8, 47.06%; 3, 60%; 3, 100%; and 1, 100%, respectively). “Mapping review” documents are generally not field-specific (6, 85.71%). Documents associated with “systematic mapping study” specifically concentrate on the software engineering field (4, 100%).

3.4 Definition components and objectives

As shown in Figure 2 and Supplement Table S4, a total of 55 definitions describing various terms or methods were analyzed, revealing that “systematic” was mentioned in 20 definitions (36.36%), “type of evidence” in 5 (9.09%), “content” in 53 (96.36%), “structure” in 25 (45.45%), “transparent” in 5 (9.09%), “visual display” in 23 (41.82%), “descriptive report” in 14 (25.45%), and “users” in 8 (14.55%). Furthermore, 53 definitions (96.36%) across various terms mentioned the objective of using relevant methods/tools to determine the current state of research, of which 14 (25.45%) further mentioned where evidence was present, and 20 mentioned where it was lacking (36.36%). Key distinctions in definitions were notably present in “type of evidence” and “visual display.” Specifically, “type of evidence” focused solely on evidence for interventional management in three definitions (37.5%) for “evidence and gap map” and one (100%) for “evidence-based policing matrix.” Meanwhile, “visual display” involved the creation of an interactive database in one definition each for “evidence and gap map” (12.5%) and “systematic map” (20%).

Figure 2 Analysis of 55 definitions across 11 components.

3.5 Terminology variations

Thirty-nine out of 68 documents discuss variations in terminology (Supplement Table S3). Seventeen (43.59%) documents examine the relationship between “evidence mapping” and “evidence map,” with nine of them (52.94%) reporting that “mapping” is a process or methodology, and a “map” is a multidimensional presentation of included studies, seven documents (41.18%) mention that these terms are used together without specifying differences, and one document (5.88%) considers an “evidence map” as a subgroup of “evidence mapping.” Seven documents (17.95%) explore the relationship between “systematic mapping” and “systematic map,” with six (85.71%) indicating that these are used interchangeably. Five documents (12.82%) investigate the usage of terms like “evidence map,” “mapping review,” “systematic map,” “mapping study,” and “mapping research,” noting a general lack of specified differences in their application. Additionally, one study (2.56%) introduces “evidence review mapping/map” as a new method focused solely on the review landscape for specific environmental topics or questions, and another describes “focused mapping review and synthesis” (FMRS) as a new review form.

Five documents (12.82%) analyze the particularity of evidence and gap map (EGM), noting that, unlike other maps, EGMs typically only include systematic reviews (SRs) and impact evaluations (IEs), with the “DPME policy relevant Evidence map” potentially including other types of research as well. EGMs are particularly noted for their intervention–outcome framework visualization and provision of user-friendly summaries. Similarly, the “evidence-based policing matrix” is described as including only IEs. Two documents (5.13%) mention the relationship between EGM, “mega-map,” and “map of maps,” stating that “mega-map” includes only SRs and other maps, while “map of maps” includes only other maps. One document (2.56%) highlights the difference between “mapping review” and EGM, stating that EGMs can either accompany an MR as a visual representation or stand independently.

Based on the analysis, as a systematic method, “mapping review” updates and replaces earlier terms such as “evidence mapping” and others including “evidence/gaps mapping reviews,” “mapping research/study.”Reference Grant and Booth 4 , Reference Sutton, Clowes and Preston 32 – Reference Booth 34 It encompasses terms used in specific fields like “systematic map” for environmental science,Reference Haddaway, Macura and Whaley 17 “systematic mapping study” for software engineering.Reference Petersen, Vakkalanka and Kuzniarz 18 Additionally, it includes newly recognized independent methodologies like FMRS,Reference Bradbury-Jones, Breckenridge and Clark 35 and “evidence review mapping.”Reference O’Leary, Woodcock and Kaiser 36 The term “evidence map” is consistently used within MRs in various forms such as tables, charts, or databases. An EGM is a special interactive form of an evidence map that can be used within MRs, other research methodologies, or as a standalone tool.Reference Saran and White 6 , Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 , Reference Campbell, Tricco and Munn 25 , Reference Snilstveit, Vojtkova and Bhavsar 37 , Reference Gaarder, Snilstveit and Vojtkova 38 The systematic definition and objective of MRs are as follows: MRs are a method of evidence synthesis that systematically collects, assesses, and synthesizes existing evidence to clarify the current state and gaps in research, thereby fostering decision-making and further research. It aims to identify areas with adequate evidence to support decision-making and highlight areas lacking evidence to guide primary research and evidence synthesis.

3.6 Timeline and comparison with other methods

As shown in Supplement Table S5, 13 documents reported the time frame required to complete an MR. Among them, five (38.46%) reported a required time frame of 1–6 months, another five reported a required time frame of 6–12 months, and three (23.08%) reported a required time frame of more than 12 months.

Twenty-eight documents discussed the differences between MRs and systematic reviews. Among them, 23 documents (82.14%) mentioned the research topic and objectives. Systematic reviews focus on specific research questions and synthesize studies qualitatively or quantitatively to address these questions. In contrast, MRs focus on broader research areas, aiming to identify the current distribution of evidence. MRs also have systematic searches but can be adjusted for different purposes (16, 57.14%), include all types of study designs (10, 35.71%), do not necessarily include quality assessments (16, 57.14%), and involve coding interesting characteristics instead of extracting research findings (6, 21.43%). Data analysis in MRs uses visualization to present evidence from different fields (19, 67.86%), resulting in an evidence map rather than a summary of effects (10, 35.71%). Stakeholder involvement is recommended in MRs (1, 3.57%).

Twenty-two documents discussed the differences and connections between MRs and scoping reviews. Among them, 11 documents (50.00%) noted similarities in research topics, searches, screening, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Compared to scoping reviews, MRs typically include a standardized or consensus-based data coding process (5, 22.73%), and quality assessment is recommended (but not mandatory), while it is generally not suggested for scoping reviews (3, 13.64%). MRs often recommend early stakeholder involvement (2, 9.09%), and their final output is an evidence map rather than a summary table of study content (7, 31.82%). The aim of MRs is to discover the current distribution of evidence rather than to summarize the content of the included studies. MRs can be distinguished from scoping reviews because the subsequent outcome may involve further review work or primary research, and this outcome is not known beforehand (11, 50.00%).

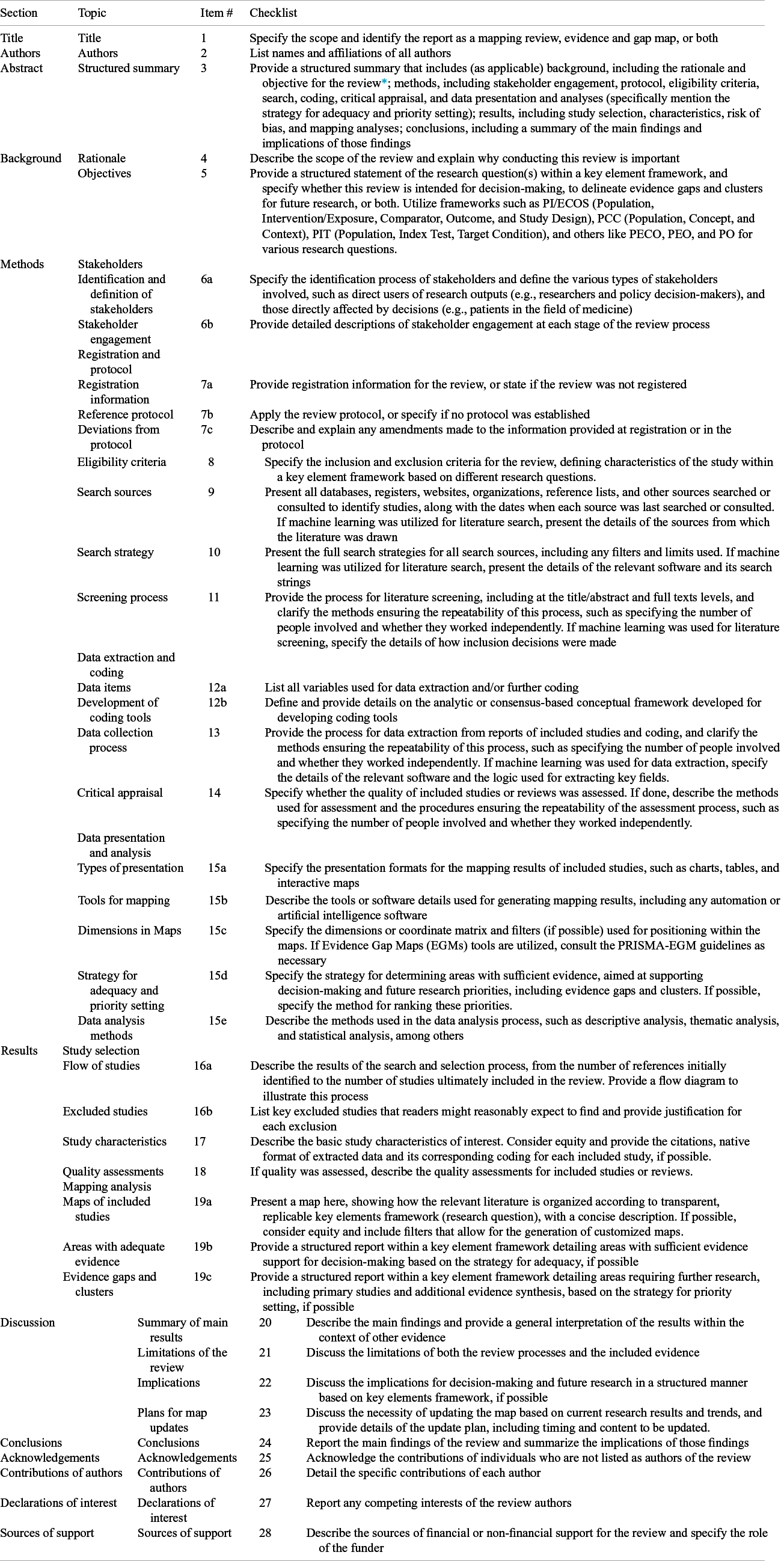

3.7 Reporting recommendations

In the 68 included documents, 57 mentioned one or more reporting recommendations for MRs, covering 28 items related to topics such as Title, Authors, Abstract, Background, Methods, Results, Discussion, Conclusions, Acknowledgements, Contributions of authors, Declarations of interest, and Sources of support. According to our protocol,Reference Li, Ghogomu and Gaarder 21 the research team (KHY, VW, EG, YFL, XH, LYH, NM, NC, FFE, XYH, SGX, and XL) summarized the different recommendations on the same topics using a predefined data extraction form and refined a new set of items that attempted to align with all the suggestions (Supplement Tables S6–9). Next, all the advisory board members (MG, HW, PN, FC, HK, and XXL) held a consensus meeting, in which the wording of 15 items was revised, and consensus was reached on each item (with materials from the meeting uploaded to OSFReference Li, Ghogomu and Gaarder 21 ).

Table 3 Twenty-eight items (including 39 recommendations) identified from guidance and methodological studies

* The term “review” in the items includes the EGM report.

The 28 reporting items formed are shown in Table 3. Among the 68 documents included, seven documents (six guidance documents and 1 methodological study) mentioned reporting on the title of an MR. Three guidance documents mentioned the authors, and four mentioned reporting structured abstracts. Fourteen documents (12 guidance documents and 2 methodological studies) discussed the reporting of rationale and objectives in the background section. Fifty-six documents (48 guidance documents and 8 methodological studies) addressed reporting on 10 methods-related items (stakeholders, registration and protocol, eligibility criteria, search sources, search strategy, selection process, data extraction and coding, data collection process, critical appraisal, and data presentation and analysis), with the median number of documents supporting an item being 34 (27, 39). Eighteen documents (15 guidance documents and 3 methodological studies) mentioned reporting on 4 results-related items (study selection, study characteristics, risk of bias in included studies, and mapping analysis), with the median number of documents supporting an item being 14.5 (11.5, 16). Twenty-five documents (23 guidance documents and 2 methodological study) discussed 4 items related to the discussion section (summary of main results, limitations of the review, implications, and plans for map updates), with the median number of documents supporting an item being 5.5 (3, 13). Six guidance documents mentioned reporting on conclusions, two guidance documents discussed acknowledgements and contributions of authors, three guidance documents mentioned declarations of interest, and four documents (3 guidance documents and 1 methodological study) discussed reporting sources of support (Supplement Tables S6–9).

Several specific reporting items were noteworthy. In the methods-related items, 22 documents (21 guidance documents and one methodological study) mention and define stakeholders, with two guidance documents (9.52%) specifically detailing the identification process of stakeholders. Additionally, 31 documents (27 guidance documents and four methodological studies) elaborate on the roles of stakeholders during various stages of development; 35 documents (32 guidance documents and three methodological studies) discuss the reporting of eligibility criteria for MRs, of which 24 (68.57%) also reporting a key elements framework for developing these criteria, including frameworks like PI/ECOS (population, intervention/exposure, comparator, outcome, and study design), PCC (population, concept, and context), PIT (population, index test, and target condition), PECO, PEO, and PO; 41 documents (36 guidance documents and five methodological studies) mention the search sources for MRs, with 31 (75.61%) explicitly reporting the use of systematic and comprehensive search methods; 39 documents (35 guidance documents and four methodological studies) discuss search strategies for MRs based on eligibility criteria or research questions, with 17 (44.74%) specifying validated search strategies for different resources. The primary reported limitations in research relate to study design, with five documents include multiple types of study designs (various primary studies and systematic reviews), two focusing only on reviews and guidelines, and one exclusively on SRs.

Furthermore, 37 documents (33 guidance documents and 4 methodological studies) mention data extraction and coding, with 26 (70.27%) mentioning the development of coding tools. Among these, 17 (65.38%) recommend that this process should utilize an analytic or consensus-based conceptual framework; 27 documents (25 guidance documents and 2 methodological studies) discuss the critical appraisal in MRs, with 13 (48.15%) recommend conducting critical appraisal (i.e., assessing the quality of individual studies) for all included studies. Seven (25.93%) suggest that quality assessment should be confined to SRs, not original studies, and eight (29.63%) view quality assessment as optional; 44 documents (37 guidance documents and 7 methodological studies) mention data presentation and analysis, all referring to types of presentation. Twenty-six documents mention presenting evidence in charts, 19 in tables, and 24 in interactive maps/databases, including tools like EGM; 15 documents mention the strategy for adequacy and priority setting, explaining how MRs utilize the evidence base to identify areas with adequate evidence to support decision-making, as well as to discover existing evidence gaps and clusters to set priorities for future research.

4 Discussion

In this scoping review, we examined guidance and methodological studies related to MRs. We uncovered substantial inconsistencies in core concepts and reporting practices. To address these inconsistencies, our research proposes a key conceptual framework derived from existing guidance and methodological studies. This framework includes standardized terminology and categorization, clear definitions, precise objectives, and comprehensive reporting recommendations.

We identified 24 relevant terms and 55 definitions for these terms (any descriptive statements). Our systematic analysis examined the occurrence of these terms over time, their focus fields, the 11 definition components identified by Ashrita Saran et al.,Reference Saran and White 6 and distinctions made between different types of MRs in the included documents. We found that primary distinctions in existing terms relate more to the research field than to the methodology itself. Terms such as “mapping review,” “evidence mapping,” “evidence/gaps mapping reviews,” and “mapping research/study” were found to describe the same methodological approach, a finding that is partially or fully supported by several included guidance documentsReference Sutton, Clowes and Preston 32 , Reference Booth 34 , Reference Wikoff, Lewis and Erraguntla 39 – 43 and a methodological study.Reference South and Rodgers 33 Notably, while the term “evidence map” is widely used and prevalent, the majority of relevant guidance documents still regard it as a tool rather than a methodological approach.Reference Katz, A-l and Girard 5 , Reference Parkhill, Clavisi and Pattuwage 44 – Reference Bates, Clapton and Coren 49 This tool consistently appears in MRs, invariably taking the form of charts, tables, or interactive databases, and is also observed in scoping reviews and network meta-analyses.Reference Saran and White 6 , Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin 20 , Reference Miake-Lye, Hempel and Shanman 26 , Reference Snilstveit, Vojtkova and Bhavsar 37 , Reference Chaimani, Caldwell, Li, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch 50 The EGM, as a special type of map,Reference Snilstveit, Vojtkova and Bhavsar 37 , Reference Gaarder, Snilstveit and Vojtkova 38 , Reference Saran 51 – Reference White 53 systematically presents evidence through an interactive database and can be utilized within MRs, other research methodologies, or independently.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 Importantly, MRs differ from other review types in that they are not focused on resolving clinical issues, determining the effectiveness of interventions (like SRsReference Shea, Reeves and Wells 54 ), or summarizing evidence (what the evidence says; like scoping reviewsReference Peters, Marnie and Tricco 19 ). Instead, MRs focus on identifying where evidence exists and where there are evidence gaps.Reference Campbell, Tricco and Munn 25 , Reference White 53 This focus is crucial for researchers and decision-makers to understand the landscape of available research and to prioritize future studies.Reference Katz, A-l and Girard 5 – Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 , Reference Snilstveit, Vojtkova and Bhavsar 37

Based on the documents included, we formed 28 recommended items, each supported or mentioned by more than one document. We identified three checklists related to MRs,Reference White, Albers and Gaarder 16 , Reference Haddaway, Macura and Whaley 17 , Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin 20 two of whichReference White, Albers and Gaarder 16 , Reference Haddaway, Macura and Whaley 17 were specifically designed for MRs. Neal R. Haddaway et al.Reference Haddaway, Macura and Whaley 17 developed reporting standards for environmental science MRs (systematic maps), while Howard white et al.Reference White, Albers and Gaarder 16 , Reference White, Welch and Marshall 55 created a reporting checklist for social science MRs (Campbell EGMs). Our preliminary set of 28 recommended items is derived from these checklists, enhanced and refined with insights from other guidance documents and methodological studies included. For example, stakeholder engagement, a critical feature of MRs, is detailed in our list under the identification and definition of stakeholders, and stakeholder engagement at each stage of the review process based on included documents.Reference Bradbury-Jones, Breckenridge and Clark 35 , Reference O’Leary, Woodcock and Kaiser 36 , Reference Haddaway, Kohl and da Silva 56 – Reference Simonovich and Florczak 60 Additionally, we have refined and developed new items that align with the distinctive features of MRs. These enhancements ensure suitability across various disciplines and fields, improve methodological effectiveness, incorporate the use of machine learning,Reference Candela-Uribe, Sepúlveda-Rodríguez and Chavarro-Porras 61 – Reference Wolffe, Whaley and Halsall 65 and consider equity.Reference Khalil, Campbell and Danial 7 Specific examples of these new items include those related to objectives, strategy for adequacy and priority setting, and mapping analysis.

5 Strengths and limitations

We employed the JBI scoping review methodologyReference Peters, Marnie and Tricco 19 to systematically gather and analyze guidance documents and methodological studies from diverse sources—including academic journals, nongovernmental organizations, governments, and university/research organizations—across various research fields. This scoping review meticulously defined the core concepts of MRs, effectively addressing and mitigating the research gaps caused by the existing confusion over terminologies and definitions within this methodology. The results will provide a crucial foundation for future methodological research and practice in this field. Additionally, our multidisciplinary team, each with at least 3 years of relevant field experience, developed a reporting item checklist applicable across various fields, based on the documents included. This checklist will serve as a critical reference for the reporting of MRs. However, there are some limitations to our study. First, as this method is rapidly evolving, there are significant discrepancies in opinions among different organizations and authors. In this context, our conclusions are based on the majority’s research rather than the consensus of all involved. Second, our items were solely dependent on the relevant documents and the opinions of the project’s advisory committee. These items have not undergone a formal Delphi survey, but they will serve as an essential reference for future methodological research, especially in the development of reporting guidelines, and MR practices.

6 Conclusion

Currently, there is a significant divergence among different organizations and authors regarding the key concepts of MRs and the standards for complete and transparent reporting. This lack of unified guidance affects primary authors, reviewers, journal editors, and other stakeholders. Based on a systematic analysis of all relevant terms, definitions, timelines, comparisons with other methods, and reporting characteristics from the 68 included guidance and methodological studies, we have proposed terminologies, definitions, categorizations, and reporting recommendations for MRs. These proposals aim to bridge existing gaps and provide essential methodological and reporting resources for this field. This comprehensive set of evidence-based reporting items will also serve as a foundation for future methodological researchers, guideline developers, and practical researchers.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: Y.L. Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: E.G. Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: XH and FE. Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: F.C., H.K., X.L., M.G., P.M.N., and H.W. Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: L.H., N.C., S.X., N.M., X.H., and X.L. Methodology, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: V.W. Methodology, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing: K.Y.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is contained in the manuscript and its supporting information.

Funding statement

The Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China: “Research on the Theoretical System, International Experience and Chinese Path of Evidence-based Social Science” (Project No. 19ZDA142); The Gansu Province Postgraduate Innovation Star Program (No. 2025CXZX-102).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/rsm.2024.9.