The rising global burden of non-communicable diseases has for decades been addressed by downstream efforts that focus on improving individual behaviours(Reference Coggon and Adams1). However, recently upstream efforts focused on societal and environmental changes have led to important population-level approaches and policies implemented in several countries to improve non-communicable diseases, including obesity and diabetes(2,3) . An important barrier to these approaches is the commercial determinants of health(Reference de Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone4,Reference Tangcharoensathien, Chandrasiri and Kunpeuk5) . These are actions, processes and ways in which commercial actors such as unhealthy commodity corporations (tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food and drink) influence health policy making and, in general, influence the environment to protect their interests(Reference Maani, McKee and Petticrew6).

There is extensive literature that shows how unhealthy commodity corporations are involved in setting health policy and research agendas globally(Reference Freudenberg7,Reference Hawkins and Holden8) . In particular, they use instrumental (action-based) and discursive (argument-based) strategies to influence science and policy surrounding public health efforts to protect well-being and healthy environments(Reference Maani, McKee and Petticrew6,Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Wate9) . Furthermore, corporations lobby and litigate against health policies and capture science by recruiting and hiring scientists to influence public discourse and position corporate interests in the public agenda(Reference Hawkins and Holden8,Reference Waa, Hoek and Edwards10,Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne11) . One key strategy is to capture health professionals and health institutions as a vehicle to achieve its interests more broadly in the global health agenda.

In the USA, one of the most important professional health associations is the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND)(Reference Nestle12–Reference Nestle14). The AND’s relationship with the food and beverage industry has been described elsewhere(Reference Storm15,Reference Simon16) . Founded in 1917 as the American Dietetic Association, the AND is the largest US-based organisation comprised of food and nutritional professionals, with approximately 100 000 dietitians and nutrition practitioners and students(Reference Right17). It is established as a 501(c)(6) trade association and certifies dieticians and nutrition practitioners in the USA and abroad(Reference Right17,18) . The AND’s stated mission is ‘to accelerate improvements in global health and well-being through food and nutrition’. AND acts as a reference for dietetics curricula accreditation and as an authority in US food policy making(19). For instance, the Academy has been influential in the process of setting US Dietary Guidelines, which are then taken into consideration all over the world in order to develop vital nutrition policy decisions(Reference Nestle14,Reference Nestle20) . The AND also provides ‘expert testimony’ including ‘comments and position statements for federal and state regulations on critical food and nutrition issues’(Reference Right17). The ‘philanthropic arm’ of the AND is the AND Foundation (ANDF), established as a 501(c)(3) charitable organisation. The ANDF does not receive member dues and relies on donations. It focuses on scholarships, awards, food and nutrition research and public education(21). The AND and the ANDF report jointly their annual activities and achievements, without a clear distinction between each another. They also share staff, including the chief executive officer and chief of operations(21).

The AND has been repeatedly criticised for its close ties to food and beverage corporations, including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and General Mills, which may undermine ‘the integrity of the professionals most responsible for educating Americans about healthy eating’(Reference Simon22). Two years after the publication of a critical report about AND’s relationship with food corporations in 2013, the ANDF announced a partnership with the food company Kraft(Reference Simon16). This collaboration, which was seen as an endorsement of some of Kraft’s products as ‘healthy’ options to include in children’s menus at schools, caused further outrage among AND’s members, public health experts and the general public(Reference Storm15,Reference Nestle20,Reference Tennille23) .

Although the AND’s relationship with the food and beverage industry has been described before(Reference Storm15,Reference Simon16,Reference Nestle20) , little is known about its relationship with other unhealthy commodity industries as well as the dynamics and evolution of such relationships. This study is the first to obtain and review AND’s internal communications and interactions between the AND and the food and beverage, pharmaceutical and agribusiness industries. We explore how these interactions evolved over time(Reference Storm15,Reference Simon16,Reference Nestle20) and how they influence the politics and decision-making of an influential professional health association, by analysing documents obtained through freedom of information (FOI) requests, filed by US Right to Know (USRTK).

Materials and methods

The USRTK, an investigative public health group, obtained internal AND communications through FOI requests. On 21 December 2017, USRTK filed a Georgia Open Records Act request to the Burke County Public Schools for email correspondence to or from Donna Martin, an AND leader who served in the AND for more than 10 years. The request asked for any mention in those records of key companies in the US food market: Splenda, Heartland Food Products Group, Tate & Lyle, Abbott Nutrition, Ingredion, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, as well as the American Beverage Association, based on previous publications pointing out some corporate relationships. Burke County Public Schools provided a total of 28 204 pages in response. USRTK sent two more FOI requests in 2019 and 2020. Burke County Public Schools responded with 53 684 pages and attachments, and then 27 more emails dated between January 2018 and March 2019. USRTK’s requests were for records after January 2013, the date when the first report criticising AND’s corporate ties was published, until September 2020(Reference Simon22).

We reviewed the documents and coded them inductively between September and November 2020. Two authors reviewed an additional 10 % of the documents to improve coding validity and reliability. The team met every 2 weeks to discuss coding and findings for consensus and reflection about the process and findings.

Additionally, to identify gaps and clarify key events described in the FOI documents, we triangulated the findings with an online search for documents in English. We searched the AND and ANDF websites, used the Wayback Machine (an online tool that captures historical versions of websites) and used Google Scholar and Google to collect further information about the AND and its Foundation, using a combination of key search terms including ‘AND’, ‘ANDF’, ‘Eat Right’, ‘sponsorship’, ‘corporate’, ‘mission’ and ‘Sponsorship task force’ as well as key names of leaders identified as relevant to our research objectives (online Supplementary material 1).

First, we mapped the actors and the timeline of events relevant to our study. We then conducted an inductive analysis. Any information from either the FOI documents or public AND documents (websites) related to corporate influence was captured.

The key information we identified in our data was (a) interactions between key leaders of the AND/ANDF and corporations, (b) corporate financial contributions to the AND/ANDF shown in Internal Revenue Service form 990 Schedule B tax returns or (c) the AND/ANDF internal policies and public positions since the Kraft partnership was announced in 2015 that generated public attention and outraged members(Reference Storm15).

The key emerging themes from that information were (a) use of revolving doors between AND’s board (BOD) of directors with corporate interests and (b) investments of AND in corporations and corporations funding AND/ANDF and their events. We also noted that corporations: (a) financed early career nutritionists and their research; (b) interfered with AND position papers on key nutrition related topics and themes and (c) led to the shaping of internal policies that benefit corporate partners.

We present a narrative review of our results in the form of mechanisms we identified in which corporations might exert their influence in and through the AND/ANDF. We also identify the ways in which the AND/ANDF have benefited from these corporate interactions over time. For the purpose of this paper, the term ‘influence’ (or ‘power’) is defined ‘as an actor’s ability to induce or influence another actor to carry out his (/her) directives or any norms he (/she) supports’(Reference Etzioni24–Reference Lukes26). We use ‘the Academy’ to refer to both the AND and ANDF, and we use ‘corporations’ or ‘industry’ to refer to unhealthy commodity corporations, including the food and beverage, pharmaceutical and agribusiness industries.

Results

Following a report published in 2013 denouncing AND’s close relationships with the food industry, the AND established a Sponsorship Advisory Task Force (SATF) to improve its Corporate Sponsorship Guidelines(27). In 2015, when AND’s partnership with Kraft was disclosed and criticised by the public, the AND/ANDF BOD dropped the deal. However, the documents gathered through FOI show they privately continued to engage with corporations by: (i) investing AND funds in shares of Nestlé, PepsiCo and several pharmaceutical company stocks; (ii) accepting corporate contributions without disclosing their size, (iii) allowing BOD members to work for or consult for companies with interests that conflict with the mission of the AND, (iv) discussing internal policies within the BOD to fit industry needs, ignoring the work of the SATF, (v) allowing corporations to support AND’s members research and (vi) releasing public positions favouring corporations.

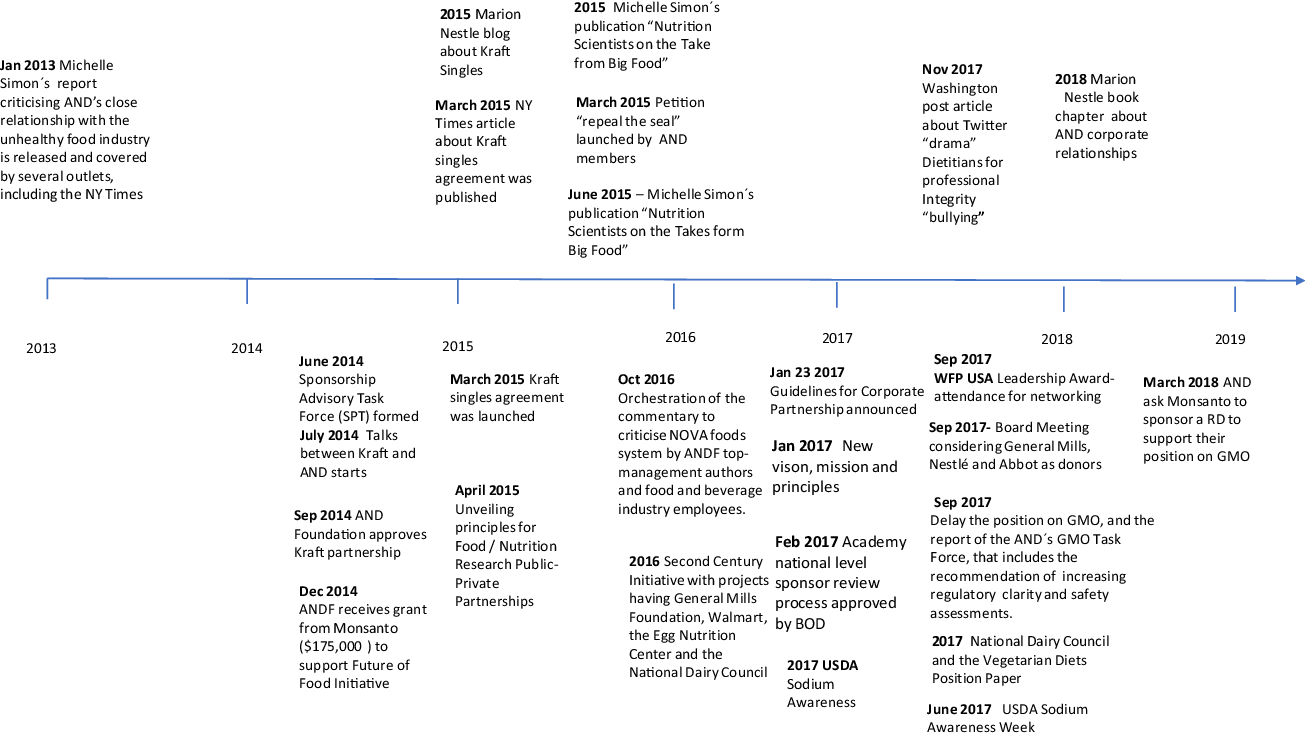

In 2017, after ‘unprecedented pressure from members and the public on the Academy’s sponsorship relationships’, the BOD presented to its members a new mission, vision and principles, accompanied by the new ‘Guidelines for Corporate Sponsors’ and ‘Guiding Principles of the Academy’s Corporate Sponsorship Program’(28,29) . Nonetheless, AND continued to accept corporate funding and engage in corporate partnerships such as a fundraising effort for their Second Century initiative and for the sponsorships for students and dietitians(30,31) . Figure 1 presents a timeline of key actions we identified regarding AND/ANDF interactions with corporations.

Fig. 1 Timeline of Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and its critics key events around corporate interactions

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation governing bodies’ interactions with corporations

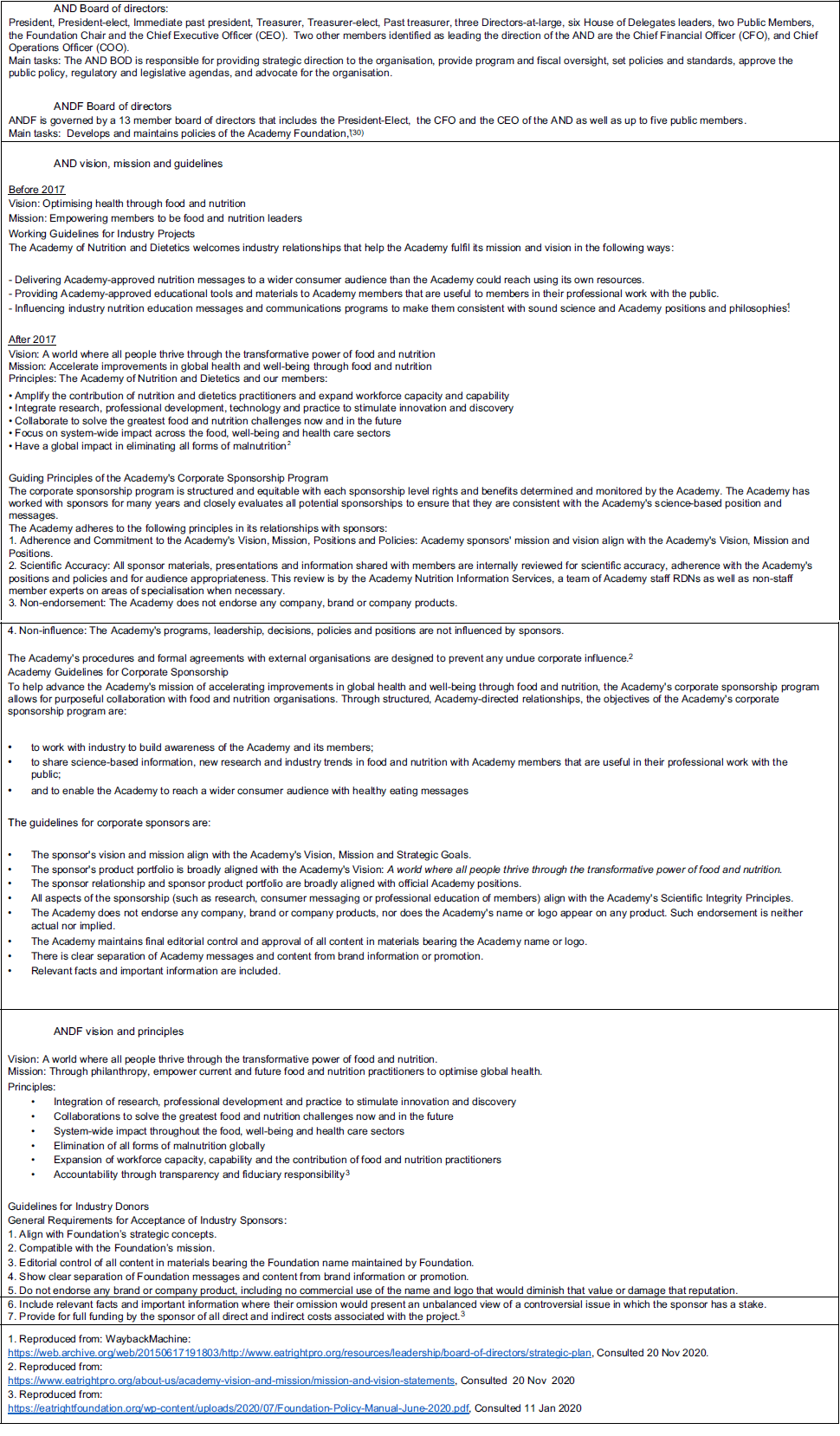

The AND’s BOD and the ANDF’s BOD are comprised of nineteen individuals and thirteen members, respectively. Details on the mission and vision of each are described in Fig. 2. Major internal policies are approved by the AND’s and ANDF’s directors and are reviewed and adopted annually(21).

Fig. 2 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and AND Foundation (ANDF) governing bodies, vision, mission and principles (from 2017)

After mapping some of the key AND and ANDF’s BOD, we identified several key members that have had close relationships with corporations throughout the years we mapped (2009–2020). Online Supplementary material 1 outlines a non-exhaustive list of these key AND members.

Donna Martin, an influential AND member who has encouraged corporate connections, has served in several positions for the Academy: as treasurer (2013–2015), president-elect (2016–2017) and president (2017–2018). In 2015, she agreed to endorse Kraft Singles, despite their poor nutritional value. Additionally, when commenting on a CFO’s report about the AND investment portfolio, she mentioned to another Academy’s executive member:

Everything looks good to me. The only flag that I saw was that PepsiCo is one of our top ten stocks (in which AND has invested). I personally like Pepsico and do not have any problems with us owning it, but I wonder if someone will say something about that. Hopefully they will be happy like they should be! I personally would be OK if we owned Coke stock!! (Donna Martin, email, 3rd January 2014)

Another AND director, Milton Stokes, was an employee at Monsanto in 2014, and from 2014 to 2020 he was the Global Lead, Public Affairs and Issues Management at Bayer Crop Science (a subsidiary of Bayer, which now owns Monsanto). Monsanto has donated at least $395 000 to the AND and worked closely with the AND, especially after Stokes joined Monsanto. For instance, in 2015 Monsanto contributed $175 000 for the Foundation’s ‘Future of Food Initiative’. The same year, Monsanto established an advisory group with fourteen former AND board members and had several AND/ANDF members as spokespeople ‘to serve on a two-year contractual basis as communication advisors’ (Milton Stokes, 11th December 2014). In 2017, he emailed several members of the AND leadership team mentioning that Monsanto has committed to support the Academy financially, and recruited AND members ‘to raise the visibility of the nutrition and dietetics community with Monsanto’ and arrange ‘a visit for the AND’s scientific officer to learn about Genetic Modified Organism (GMO) use in Nairobi, and Kenya’.

In 2017, as an employee of Monsanto, Stokes contacted two leaders to further collaborate with the AND to align agendas around sustainable diets, mentioning other industry-funded organisations involved:

‘to support convening experts from various disciplines to share the language, metrics and goals for each [sector] and then align on a research agenda that would allow for a more meaningful discussion of the science, including an acknowledgement of trade-offs. This work started already by ILSI’. (Milton Stokes, 11th May 2017)

In September 2017, as member of the BOD, Stokes invited the AND CEO to attend the World Food Program-USA Leadership Awards ceremony to connect with leaders on the topic (sustainable diets) as an attempt to ‘further advance the agenda on sustainable diets’ (15th September 2017), calling it a strategic meeting with government, illustrating the continued close relationships with Monsanto.

The Academy’s corporate financial contributions and its corporate investments

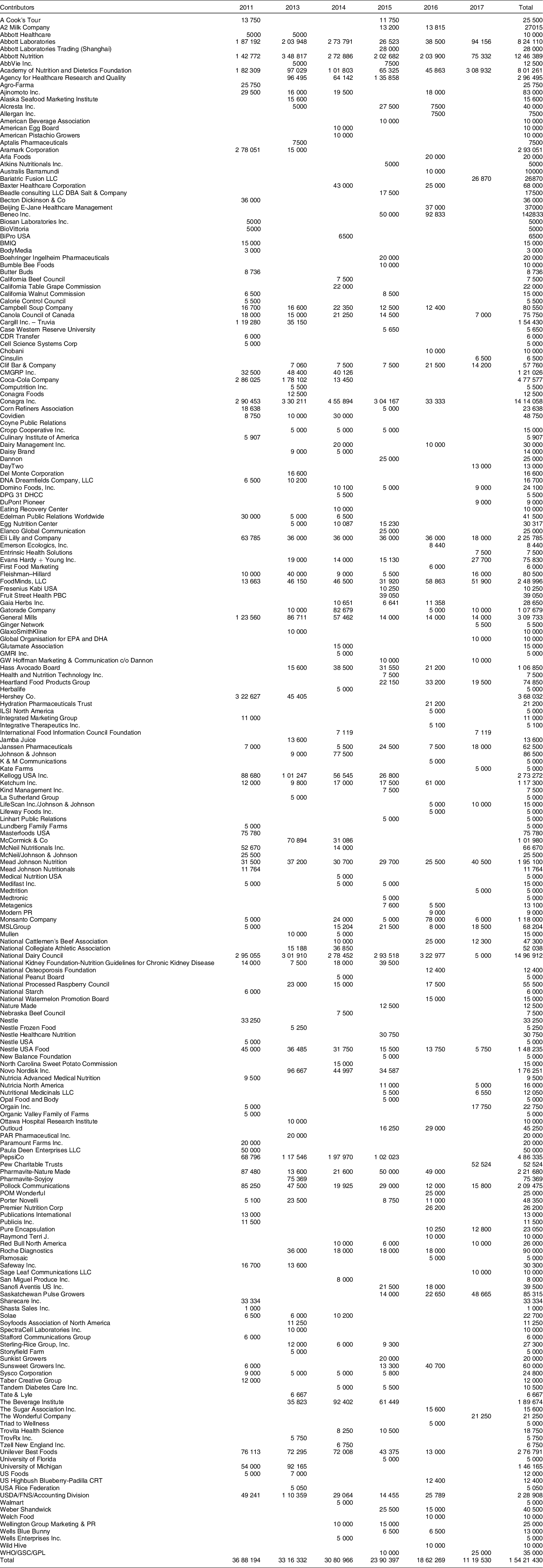

The AND has maintained financial ties to food, pharmaceutical and agribusiness corporations, despite criticism and the potential reputational risks identified by some ex-Academy members(32). We found three main types of financial ties. First, FOI documents revealed the corporate financial contributions to the AND for the years 2011, and 2013 to 2017 (Table 1). In 2011, the AND received more than US$300 000 from Hershey Co., a chocolate manufacturer, and nearly US$300 000 from the National Dairy Council (NDC), Conagra, Coca-Cola and Aramark, a company providing food services. Abbott, a pharmaceutical company selling infant formula, as well as General Mills and Cargill each donated more than US$100 000 in 2011 and maintained substantial donations from 2013 to 2017. Food and beverage companies such as Nestlé, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, with the exception of General Mills, reduced their contributions over time. Nevertheless, contributions from companies such as Pharmavite-Nature Made and Abbott increased substantially during this same period. Overall, contributions shrunk by more than US$600 000 in 2015 and by more than US$500 000 in 2016, in respect to previous years.

Table 1 Corporate and organisational contributions to the AND 2011–2017 in USD

AND, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; CDR, Constant Default Rate; DPG, Deferred Payment Guarantee.

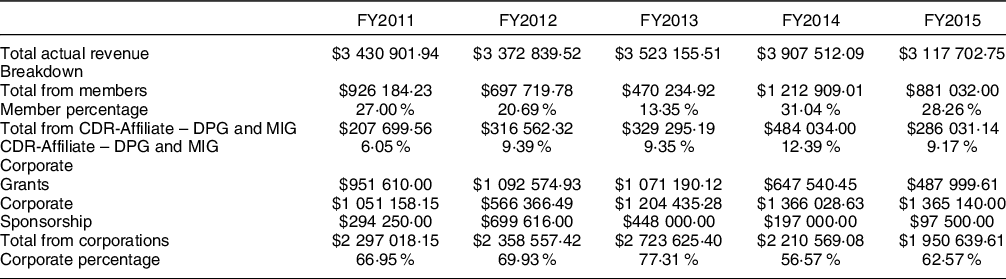

Second, FOI documents showed large corporate donations to the ANDF from 2011 to 2015, listed in Table 2. Between 2011 and 2014, the Foundation received more than US$2 million each year from corporations, representing approximately a third of its total revenues for that period. In 2015, the corporate funding dropped under US$2 million, but corporate funding still represented more than 62 % of the ANDF’s revenues.

Table 2 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation revenues 2011–2015

CDR, Constant Default Rate; DPG, Deferred Payment Guarantee; MIG, Minimum Income Guarantee.

Third, our findings suggest that ANDF is a means for corporations to reach out to young students and professionals. From 2009 to 2015, corporate contributions to the Foundation were US$15 million. Of these funds, more than US$6 million were transferred to AND members through the distribution of awards, scholarships, research grants, fellowships and other ANDF-led programmes. Of these, US$4·5 million went to an initiative called the ‘Champions Program’, which granted funds to hundreds of non-governmental organisations to support projects ‘promoting healthy eating and active lifestyles for children and their families’ (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation Industry Foundation Support Fundraising – Industry Revenue, 2015). At least US$500 000 went to stipends for public nutrition education programmes. Between 2009 and 2012, the General Mills Foundation provided an additional US$2 million directly to the Champions Program and summed a total US$7·5 million in 2015 after 13 years of donations(33).

Lastly, internal AND documents from 2015 to 2016 show that AND invested its funds in the stock of several pharmaceutical companies such as Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Perrigo Co., Pfizer Inc., Allegra, Merck & Co., and some food and beverage companies such as PepsiCo, Nestlé and J.M. Smucker’s Company.

Corporate co-opting of nutritionists and dietetic professionals through the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation

The AND certifies US professionals and develops content for continuing professional education as a ‘requirement for’ certification and ‘to build’ knowledge and advance nutritionists’ careers(34). Also, the AND provides a toolkit for individual or organisational members to build their own workshops with continuing professional education credits. Some of the topics of such continuing professional education resources were sponsored or aligned to industry’s interests. For example, ‘Whole Grain Product: Menuing and Getting Kids to Like Them’ was sponsored by General Mills (DM email, 12th June 2015). The ‘Certificate of Training in Childhood and Adolescent Weight Management’ and ‘Changing the Way We Look at Agriculture’ were supported by the National Dairy Council.

The AND also publishes the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal has become a means for the AND to publish its official positions on certain topics(Reference Lipscomb and Brown35). For example, the AND has published controversial positions that have been amended over time and appear to be aligned with corporate interests. For instance, in 2017 the AND CEO mentioned to some directors she received an email from the president of the National Dairy Council, concerned about the AND position on vegetarian diets published in the journal(Reference Melina, Craig and Levin36). The Council’s president indirectly questioned the science behind the public statement mentioning that the National Dairy Council was funding the AND. According to the AND CEO:

[I] Heard an earful yesterday on the phone from Jean as President of Dairy (NDC) about our Vegetarian position paper (six months later?) that has a line in it about dairy and meat. Nothing in the paper says don’t eat dairy or meat or be a vegetarian or vegan but she was saying that Dairy is helping us with funding to elevate the Academy’s science and evidence and it’s so disappointing. I resented the correlation of the sponsorship. (Patricia Babjak, 28th April 2017)

The original position paper on vegetarian diets published in 2015 was retracted at the request of the AND’s Academy Positions Committee, as they ‘became aware of inaccuracies’ and a new version was made public in December 2016, eliminating any mention of specific animal source foods(Reference Melina, Craig and Levin36). These actions resonate with the commitments to ‘return specific rights and benefits’ to AND/ANDF sponsors, as mentioned in internal documents (JS email, 6th July 2015) but contradict AND’s principle of ‘non-influence’ (point 4, Fig. 2)(37).

Internal policies and politics favouring corporate ties: the Sponsorship Advisory Task Force

The AND has changed its internal policies to address criticism of its corporate relationships, notably through its SATF. The SATF was established in 2014, following ‘internal and external criticism’ and for ‘enhancing communication and trust among members and the public, and facilitating transparency of process and decisions’(38) (Fig. 2(b)). The SATF was composed of eight AND members and one former director. The advisory group was established to make recommendations and guidelines and review AND’s and ANDF’s policies and practices on corporate-funded programmes and corporate donations.

After the SATF’s produced recommendations, the AND updated its Guidelines for Corporate Sponsors. These guidelines require the sponsor’s vision and mission to be aligned with the AND’s vision and mission, that its product portfolio is ‘broadly’ aligned with official AND’s positions and that the sponsorship complies with the Scientific Integrity Principles, principles developed by the International Life Science Institute (ILSI), an industry-funded organisation, in collaboration with the AND in 2015 (Fig. 2)(Reference Mialon, Ho and Carriedo39). The AND/ANDF also made clear that ‘it does not endorse any company, brand or company products, nor does the AND name or logo appear on any product’(27).

The SATF was not asked to approve the 2014–2015 Kraft-AND partnership. But AND’s strategic communication team commissioned risk assessments ‘with input from an outside source specialised in risk assessments’ noting that some AND members, ‘a vocal, but minor contingent’, would protest the partnership (Kathy Warwick email, 29th March 2015). The BOD weighted the risks and despite the results of the external risk assessment decided to go ahead with the Kraft partnership. AND’s COO conducted a ‘due diligence’ before deciding to ‘accept Kraft as a National Level Sponsor’ with an ‘unrestricted gift to Kids Eat Right’, recognising that ‘we risk alienating members and/or donors who are not supportive of opportunities to work with big industry’. To accommodate the partnership and justify it Donna Martin, who later became the AND president, had several conversations in August 2014 with the AND’s CFO trying to argue that Kraft Singles could be considered healthy:

We need to change the part that says that the Kraft reduced fat Singles would not meet (USDA) guidelines. Kraft Singles would not meet guidelines, but the reduced fat Singles would (Donna Martin email, AND President, August 29th, 2014).

A majority of AND members, when learning about the Kraft partnership, wrote to the BOD criticising the lack of transparency and their management of the Kraft partnership(Reference Storm15). A member of the BOD talked about the discontent among members and suggested hiding a new agreement being negotiated with Monsanto at that time in order to avoid any further criticism:

‘Dear Board, I think this has moved from educating the members and being appalled that they would believe the New York Times (in relation to their reporting about the Kraft scandal), to an issue of great dissatisfaction with corporate sponsorship, a very sensitive issue and one that we know members are sensitive about, some super sensitive (…) Lets respect and hear them out. They don’t want or deserve a pat on the head. And please, let’s not announce Monsanto any time soon.’ (Aida Miles, ANDF Director, March 2015)

Since the establishment of SATF some food and beverage corporations were no longer listed on the AND sponsorship programme, such as Coca-Cola and Nestlé. Yet, others replaced them such as Abbot Nutrition, Beneo Inc. (food ingredients company), Mead Johnson and others (see Table 1). Some other food and pharmaceutical corporations were still mentioned in AND/ANDF’s annual reports until 2019, either as sponsors or supporters(40).

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics allowed companies to purchase rights and benefits

According to AND/ANDF internal communications, AND distinguishes its ‘sponsors’ from its ‘supporters’. Corporate sponsors ‘pay a fee, and in return the Academy provides a right or a benefit’ (JS email, 6th July 2015). Corporate ‘supporters’ provide ‘a charitable contribution with no (explicit) expectation of a commercial return’ (JS email, 6th July 2015). We found several cases when AND has legitimised some corporate positions, which may relate to corporations procuring rights or benefits.

First, we found that the AND established a GMO Task Force in 2017 to work on the AND’s position on GMO. The task force’s report supported the National Academy of Science report, leaning to a critical view of GMO, that would have been a direct criticism of the products of some sponsors, including Monsanto, as discussed by three members of the AND’s BOD (Patricia Babjak, CEO, 8th September 2017). These directors tried to delay the report’s delivery after the September 2017 board meeting, where corporate funding opportunities were to be discussed. Some of the potential sponsors were Abbott, General Mills and Nestlé, and these partners would have had ‘representation in the Board of Directors’ and they ‘will accelerate their organisational nutrition commitments and global public health’ (Paul Mifsud, CFO, 8th September 2017). Thus, there was the intention to delay any potential criticism about GMO.

Second, we found that in 2016 the AND engaged with the American Society for Nutrition, the Institute of Food Technologists and the International Food Information Council (funded by corporations) to put together a ‘Food and Nutrition Science Solutions Task Force’. They also agreed to write a commentary for a special issue of the Journal of Public Health, criticising the NOVA classification of foods, based on their level of processing showing that the consumption of ultra-processed food lead to ill health. At least two of the authors of the proposed papers had ties with the food industry at the time. One was part of the Gerber Foundation and the other was part of the General Mills speaker’s bureau. This group never published the paper, but one of the authors who was an AND member published a criticism of the NOVA classification in a different journal in 2018.

In a final example, in June 2017, the AND CEO emailed other directors that AND had been invited by the US Agriculture Secretary to join the USDA’s new Sodium Awareness Initiative. The goal of this initiative was to reduce sodium in school meals. One director questioned the decision to engage in that initiative, saying that ‘although this is a tremendous HONOR, we do seem to be talking out of both sides of our mouth in regards to sodium’, and recognised that ‘I am well aware that the sodium restrictions in school meals cannot be achieved without industry help, and I am PROUD that we are at the table’. This member pointed out some inconsistencies with AND’s previous actions. In 2015, the AND indeed asked for the US Dietary Guidelines Committee to ‘reconsider the sodium recommendation of 2300 mg/day (considered too low)’, as ‘there is a distinct and growing lack of scientific consensus on making a single sodium consumption recommendation for all Americans, owing to a growing body of research suggesting that the low sodium intake levels recommended by the DGAC are associated with increased mortality for healthy individuals’.

Discussion

Our findings illustrate different ways in which the AND and its Foundation have interacted and continue to interact with unhealthy commodity corporations in a symbiotic relationship. In a prominent national professional association with high impact on the US food and nutrition practice and US consumers, there are ongoing interactions with food, pharmaceutical and agribusiness corporations. Corporations contribute financially to the AND and its Foundation. The AND/ANDF act as a pro-industry voices in some policy venues, including some of their public positions that clash with AND’s mission to improve health globally.

We have found some internal organisational issues that may compromise the Academy’s mission to improve health. AND leaders have been involved in controversial decisions about corporate relationships and were not removed from their leadership roles despite public disclosure of these relationships. AND has not required its BOD to publicly disclose conflicts of interest, and such disclosures have not been required for membership, as other professional associations have done(Reference Mialon, Ho and Carriedo39). This research illustrates the extent to which corporate funding enables corporate influence at AND specifically, and across such partnerships more widely. It also suggests this has been normalised, considering the nature of the agreements made and the relationships formed. Although AND has changed some of its internal policies to manage corporate interference and funding, it continues to advance corporate interests in several ways and serves as voice for its corporate sponsors(Reference Mokdad, Serdula and Dietz41,Reference Marks42) .

The current AND/ANDF policies and public statements are not sufficient to explain why the AND continues to accept financial contributions of corporations whose products (such as ultra-processed foods and formula milks) are associated with ill health(Reference Askari, Heshmati and Shahinfar43). We note however that the association is registered as a trade association, meaning it is an association having common business interests and that can receive contributions from corporations, clashing with its mission statement.

This paper supports previous findings that the AND has implemented minor ‘reforms’ rather than eliminating corporate sponsorship and requiring disclosure of conflicts of interest, with no real perceived commitment to change(Reference Marks44). Our findings suggest that even though some AND members have tried to make AND more transparent, these efforts have not prevailed, and to this day, some basic financial facts and decisions remain secret.

Our results show striking similarities to other cases of institutions captured by corporations, such as the International Life Science Institute and the Global Energy Balance Network, orchestrated by the soft drink industry to promote its commercial agenda in scientific institutions(Reference Serodio, Ruskin and McKee45,Reference Steele, Ruskin and Stuckler46) . For example, in the past, the pharmaceutical industry has been criticised for paying physicians to make income-driven choices leading to the introduction of regulatory frameworks such as the Code of Interaction with Health Care Professionals in the USA or the Physician Payment Sunshine Act to avoid any negative impact of those practices on population health(Reference Dorfman47,Reference Santhakumar and Adashi48) . There is no such law or rule governing for the interactions between food corporations and nutritionists or dietitians, and they continue to receive grants, scholarships and awards funded by corporations through the ANDF levering their way to continue to influence the profession(Reference Mialon, Ho and Carriedo39,Reference Mialon, Vandevijvere and Carriedo-Lutzenkirchen49) .

Limitations

This study does not include interviews with key actors, which would have provided a detailed narrative of actions and decisions in the AND and ANDF and would have helped contextualise our findings. In addition, some of the information about the AND/ANDF past policies was no longer available online when conducting the study. While this study is not a thorough review of the AND and ANDF policies and procedures around corporate sponsorships and interactions with corporations, it provides insights into several decisions and communications that might have influenced some decisions inside the organisation, pointing to the recent and current internal AND policies, procedures and financial contributions from industry actors. Our analysis was exploratory and not meant to be exhaustive. Hence, the examples presented here only represent a snapshot of the interactions between the AND/ANDF and corporations.

Conclusion

AND and its Foundation assist the food and beverage, pharmaceuticals and agribusiness industries through their large network of professionals and students, their lax internal policies on corporate partnerships and their topical position papers. The AND/ANDF have been supported financially by these corporations throughout the years despite public criticism and internal organisational changes. With a registration as a trade association, the AND and corporations interact symbiotically. This sets a precedent for close corporate relationships with the food and nutrition profession in the USA, which may negatively affect the public health agenda in the USA and internationally.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Kate Tasker and Rachel Takata of the UCSF Industry Documents Library for archival support and assistance and to Dr. Cristin Kearns for substantive input on this research. Financial support: The work was supported by Arnold Foundation. The funders had no role in design, conduct, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. Authorship: G.R. contributed to data collection, I.P., A.C., E.C. M.M. contributed with analysis and interpretation. A.C., I.P. drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to revision for important intellectual content. Ethics of human subject participation: N/A.

Conflict of interest:

GR is executive director of US Right to Know, a non-profit investigative public health organisation. Since its founding in 2014, USRTK has received the following contributions from major donors (gifts of $5,000 or more): Organic Consumers Association: $1 032 500; Dr. Bronner’s Family Foundation: $575 000; Laura and John Arnold Foundation: $397 600; Centre for Effective Altruism: $200 000; Ryan Salame: $160 000; US Small Business Administration: $119 970; Westreich Foundation: $110 000; Ceres Trust: $70 000; Schmidt Family Foundation: $53 800; Bluebell Foundation: $50 000; CrossFit Foundation: $50 000; Thousand Currents: $42 500; San Diego Foundation: $25 000; Community Foundation of Western North Carolina: $35 000; Vital Spark Foundation: $20 000; Panta Rhea Foundation: $20 000; California Office of the Small Business Advocate: $15 000; Pollinator Stewardship Council: $14 000; Swift Foundation: $10 000; ImpactAssets ReGen Fund: $10 000; Lilah Hilliard Fisher Foundation: $5 000; Aurora Foundation: $5 000; Janet Buck: $5 000.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001835