1 Introduction

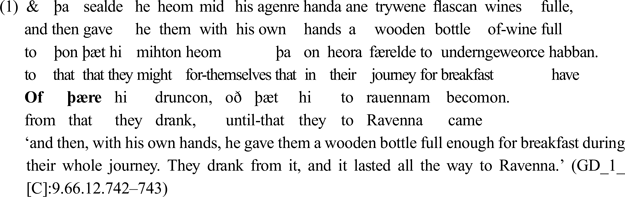

A considerable body of work over the last decade or so has shown that word order in Old English (OE) is more flexible than in later stages of the language and is partly determined by information structure. Information structure explains both some of the variation in object placement in OE (Taylor & Pintzuk Reference Taylor and Pintzuk2012a, Reference Taylor and Pintzuk2012b, Reference Taylor and Pintzuk2014; Struik & van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020, Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022) and subject placement (Bech Reference Bech2001; Hinterhölzl & Petrova Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2010; van Kemenade, Milićev & Baayen Reference Kemenade, Milićev, Baayen, Gotti, Dossena and Dury2008; van Kemenade & Milićev Reference Kemenade, Milićev, Jonas, Garrett and Whitman2012). Information structure is also a key factor in scenarios for word order change after the OE period; specifically, Los (Reference Los2009) argues that the loss of V2, which resulted in a subject-initial grammar, compromised information structure to such an extent that new structures emerged and others increased in frequency to compensate for the loss: stressed-focus it-clefts and cross-linguistically rare passives. Los further proposes that V2 is not just a syntactic constraint, but also entails a specific use of the clause-initial position in the case of non-subjects, so-called local anchoring (Los & Dreschler Reference Los and Dreschler2012). Consider the clause-initial PP of þære in (1):

Of þære in (1) refers to the bottle, newly introduced in the preceding discourse and anchored ‘locally’ to the immediately preceding sentence. Note that this information in clause-initial position is not necessarily contrastive and/or emphatic, i.e. it is information-structurally unmarked. A sentence like (1) is difficult to replicate in Present-day English (PDE), as non-subjects in clause-initial position have become restricted to contrastive and frame-setting interpretations: adjuncts like Of þære could be unmarked themes in OE in the sense of Halliday (Reference Halliday1967), while they are marked themes in PDE, where only subjects can be unmarked themes. Even if we assume that demonstratives as independent pronouns have more restricted functionality in PDE than in OE, this cannot by itself account for the infelicity of clause-initial From that in PDE, as the expanded alternative, From that bottle, would still be interpreted as having a specific emphasis that is not present in the OE sentence. Los (Reference Los2009) argues that the loss of V2 in the fifteenth century led to a stricter mapping between syntactic function and information-structural status: subjects as the default expression of given information, including links to the preceding discourse, complements and objects as the default expression of new information. The pre-subject position, which remained available to objects and adjuncts, also acquired a specific, contrastive, information-structural function, which was not compatible with non-contrastive local anchors. The subject appears to have taken over the local anchoring function. PDE allows subjects where V2 languages like Dutch or German would use adverbials, as is clear from e.g. Dutch–English translation studies like Hannay & Keizer (Reference Hannay and Keizer1993) or Lemmens & Parr (Reference Lemmens and Parr1995), which advise against a literal translation of examples such as (2a) (relevant items in bold):

(2)

(a) En daarmee was de tragedie van Bergkamp compleet.

(b) And with that Bergkamp's tragedy was complete.

(c) And that made Bergkamp's tragedy complete. (Hannay & Keizer Reference Hannay and Keizer1993: 68)

The literal translation as in (2b) renders the Dutch clause-initial adverbial with a clause-initial adverbial in PDE, but is less felicitous than (2c), which reworks the adverbial into a subject expressing the link to the previous sentence. Similar observations can be found in comparative studies of PDE and German, another V2 language (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1974: 11; Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: 58–61). Komen et al. (Reference Komen, Hebing, van Kemenade and Los2014) provide quantitative evidence for this change in function of the subject in the history of English, whereas other studies connect the increased functional load of the subject to an increased and/or extended use of passives, middles and so-called permissive subjects (Los Reference Los2009, Reference Los, Cuykens, De Smet, Heyvaert and Maekelberghe2018; van Gelderen Reference Gelderen2011; Los & Dreschler Reference Los and Dreschler2012; Dreschler Reference Dreschler2015, Reference Dreschler2020). An example of an extended use of the passive is the exceptional case-marking (ECM) construction with verbs of thinking and declaring like report in (3):

(3) This mushroom is reported to have a lobster like flavor when cooked.

(http://caldwell.ces.ncsu.edu/2015/01/336308/. Accessed 19 Oct 2015, via

WebCorp, www.webcorp.org.uk)

Many of these verbs do not have an acceptable active counterpart (*They reported this mushroom to have a lobster like flavor when cooked); Birner & Ward (Reference Birner and Ward2002) label the passive ECM-construction an ‘information-packaging’ device, its primary function being to allow discourse-old information to be expressed as a subject.

Examples of middles are (4)–(5) (relevant verb in bold):

(4) Speaker A: It seems to be impressing our American friend.

Speaker B: Americans impress easily (Inspector Lewis, series 2, episode ‘And the moonbeams kiss the sea’, quoted in Dreschler Reference Dreschler2015: 372)

(5) I think [Kate Middleton] photographs better than she knits. (Graham Norton Show, series 9, episode 1, 15 April 2011, quoted in Dreschler Reference Dreschler2015: 372)

Note that these verbs are not used with their default valencies: their subjects are not agents but patients. The productivity of middle formation in English is particularly exemplified in (5), meaning, as it does, ‘Kate Middleton is more photogenic than she is knittogenic’ (in the context of an enthusiastic knitter who knits effigies of members of the royal family). Key in these developments is the increased functional load of the subject that is at least partly the result of the loss of discourse links expressed by initial adjuncts – what we will call ‘local anchoring’.

This article will build a quantitative case for the loss of local anchoring by analysing clause-initial PPs in the history of English, annotated with quite minimal information: just their referential status. The goal is to uncover the decrease of local anchoring, and discover what restricted its use in the later periods. The extraordinary thing about these adjuncts is that even though their frequency was greatly reduced over time, they were not completely lost.

2 Background

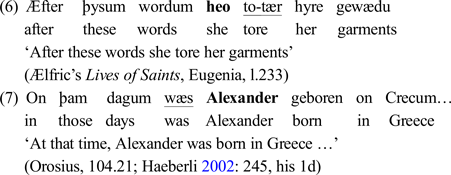

Following van Kemenade (Reference Kemenade1987), OE has generally been analysed as a V2 language, meaning that – as in present-day languages such as Dutch and German – the finite verb occurs in second position in main clauses. Subject-finite verb inversion was categorical in some contexts such as questions, negative-initial clauses, and clauses introduced by a temporal adverb þa or þonne ‘then’. But V2 in OE differed from the V2 pattern as it is found in present-day V2 languages. Outside the categorical contexts, OE shows alternation between V2 and V3, with pronominal subjects typically found with the latter pattern (as in (6)), and nominal subjects (as in (7)) with the former (subjects in bold, finite verb underlined):

The consensus in the literature appears to be that the finite verb in OE only moves to C when the first constituent is a question-word, a negated constituent, or a member of a restricted set of adverbs (þa or þonne ‘then’, swa ‘so’ or þus ‘thus’), while other types of first constituents – like the adjuncts in (6) and (7) – trigger movement of the finite verb to a lower head (AgrS in Haeberli Reference Haeberli, Zwart and Abraham2002; F in van Kemenade & Westergaard Reference Kemenade and Westergaard2012: 91), with the pronominal subjects moving to the specifier of that head, while full NP subjects remain in the default subject position. This means that (6) and (7) both have the finite verb moved into the lower head (AgrS/F) rather than C, even though their surface order is different. In recent years, this variation has been reassessed in terms of its information-structural properties: the variation in (6) and (7) is to a large extent governed by the information status of the subject, with new subjects generally following the verb and given or discourse-old subjects preceding the verb (Bech Reference Bech2001; van Kemenade Reference Kemenade2012; van Kemenade & Westergaard Reference Kemenade and Westergaard2012). In fact, Hinterhölzl & Petrova (Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2010) and Los (Reference Los2012) propose that in sentences such as these, movement of the finite verb in OE to the lower AgrS/F position may originally have arisen as a marker of information structure, separating given or background elements from new elements, while movement to the higher position, C, may have arisen as a way to mark off a focus domain. Hinterhölzl & Petrova (Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2010: 319) even call V2 order in OE an ‘accident’: a surface effect which happens when there is only one background element.

Information structure also plays a role in the V2 system in another respect – and this is our main focus in this article. As Los (Reference Los2009) proposes, following Halliday (Reference Halliday1967), the subject in PDE is the unmarked theme, and adverbials and complements are only chosen as themes, i.e. as initial elements, for contrast and emphasis. The following examples illustrate typical clause-initial non-subjects in PDE (in bold).

(8) This I can play.

(9) In the latest book, Asterix and Obelix are tasked with protecting Adrenaline from the Romans, who have captured her father.

(Both examples from guardian.co.uk, accessed 25 October 2019)

In (8), the object is fronted, and is contrastive, which is appropriate, as the immediately preceding text describes failed attempts at other games. Example (9) illustrates frame-setters, which – in Krifka's (Reference Krifka2008: 55) definition – function to ‘set the frame in which the following expression should be interpreted’. The proposition in (9) holds for the domain of the latest book in the series. Krifka points out that an important aspect of frame-setting is that there is a sense of implied alternatives when frame-setters are used, which means that they are contrastive or, in Krifka's terms, focused. This fits example (9): it is in this book and not the earlier books that Asterix and Obelix are protecting Adrenaline. Fronted objects and frame-setters both represent cases where there is a clear motivation for deviating from the unmarked option of a subject as theme. Biber et al.'s (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 772) extensive corpus data on adverbials provide further support for this observation that non-subjects are marked: even though adverbials can occur in initial position, they most commonly occur in final position, and much less frequently in initial position. It is especially circumstance adverbials that are ‘very marked’ in initial position (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 803); example (10) illustrates the use of such a circumstance adverbial, with the next sentence indicating a contrasted option (both adjuncts in bold). Stance adverbials, as in (11), and linking adverbials especially, as in (12), are more frequent in initial position.

(10) In many cultures, the practice of abstaining entirely from animal produce has an established history: with their belief systems rooted in nonviolence, many Rastafarians, followers of Jainism and certain sects of Buddhism have been swearing off meat, fish, eggs and dairy for centuries. In large swathes of the west, though, public awareness of what veganism actually entails has been sketchy.

(11) Needless to say, Johnson wants to push ahead, without installing safeguards.

(12) In contrast, it's unusual for disabled actors to be hired to play characters who aren't defined by their disability […].

(All examples from guardian.co.uk, accessed 28 October 2019)

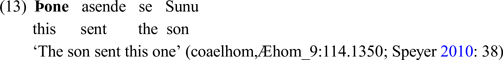

In OE, however, non-subjects in initial position are more versatile than they are in PDE, syntactically as well as information-structurally. In particular, fronted objects and clause-initial PPs are less restricted. Speyer (Reference Speyer2010) identifies a type of object fronting of a demonstrative pronoun in OE which – unlike PDE object fronting – is anaphoric; it does not present new information and is not contrastive, but just serves as a link to the preceding discourse, which has introduced the antecedent, se frofergast ‘the Holy Spirit’.

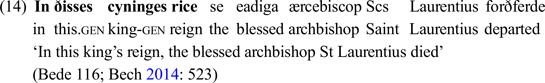

Dreschler (Reference Dreschler2015) and Bech (Reference Bech2014) provide similar examples for clause-initial PPs:

The fronted object in (13) and the PP in (14) are typical examples of local anchoring: there is a local link to the immediately preceding discourse. Crucially, these local anchoring phrases in initial position appear to be information-structurally unmarked, in the sense that they do not necessarily receive any special emphasis or indicate contrast or focus.

Some aspects of the decline of local anchoring have been addressed in earlier work. Los & Dreschler (Reference Los and Dreschler2012) and Dreschler (Reference Dreschler2015) present data that show a decrease in adverbials and objects in first position, while there is an increase in clause-initial subjects from the OE period through to the Late Modern English (LModE) period. The decline of clause-initial PPs that encode given rather than new information from late Middle English (ME) onwards is charted by Pérez-Guerra (Reference Pérez-Guerra2005: 357ff.). The discourse-linking aspects of the initial position in earlier periods is studied by Los & Dreschler (Reference Los and Dreschler2012), Bech (Reference Bech2014) and Dreschler (Reference Dreschler2015), who all show a decline in clause-initial prepositional phrases with anaphoric elements or based on information status. While these earlier studies lend support to the overall hypothesis about the decline of local anchoring, the nature of the problem – involving information structure rather than syntax – makes it difficult to pinpoint which period is particularly significant. Manual information-structural annotation leads to small datasets; scholars also differ in how they operationalize the relevant information-structural notions and work on different texts. The present study aims to contribute to the testing of the hypothesis by presenting data from a large-scale corpus study with a single consistent system for information status coding.

3 Methodology

We will investigate PPs that occur as initial constituents in main clauses, using the syntactically parsed corpora of historical English: The York–Toronto–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (YCOE; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Warner, Pintzuk and Beths2003); The Penn–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English, 2nd edition (PPCME2; Kroch & Taylor Reference Kroch and Taylor2000); The Penn–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English (PPCEME; Kroch et al. Reference Kroch, Santorini and Delfs2004) and The Penn–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Modern British English (PPCMBE; Kroch et al. Reference Kroch, Santorini and Diertani2010). The earlier subperiods of the Middle English corpus, the PPCME2, are somewhat problematic: many of the texts in the first subperiod, M1 (c.1150–1250), are copies or adaptations of OE texts, or have such a complex history that the dating of the manuscript is unlikely to bear any correspondence to the actual date of composition (see e.g. De Bastiani Reference De Bastiani, Los, Cowie, Honeybone and Trousdale2022: 121–2 for discussion and further references), while for the second Middle English subperiod, M2 (c.1250–1350), there is very little textual material. This notorious M2 data gap is unfortunate, as this appears to be an important period for syntactic change (see e.g. Truswell et al. Reference Truswell, Alcorn, Donaldson, Wallenberg, Alcorn, Kopaczyk, Los and Molineaux2019: 21–2).

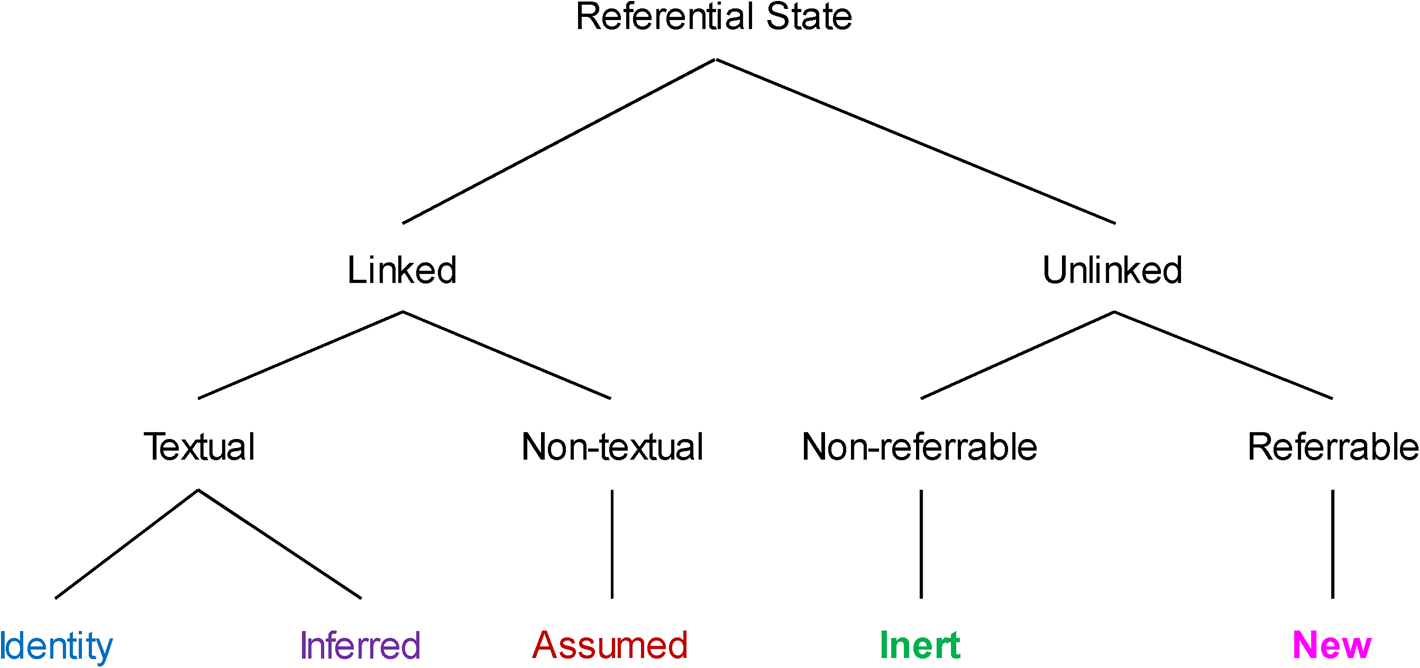

The hypothesis is that OE will have higher frequencies than later periods of NPs inside clause-initial PPs that present ‘given’ information by referring back to a referent in the immediately preceding discourse, and lower frequencies of NPs that are ‘new’ information, such as frame-setters that demarcate the context in which the following proposition is true. To test the hypothesis, all clause-initial PPs of the Penn–Helsinki corpora were annotated following the Pentaset-annotation scheme (Komen, Los & van Kemenade Reference Komen, Los and van Kemenade2023), marking the NP inside the PP as having a previously mentioned referent or not; and if yes, what the relationship is between the NP and that referent. The Pentaset categories (figure 1) build on Prince's (Reference Prince and Cole1981) categories, with some streamlining.

Figure 1. The referential state primitives in the Pentaset (Komen, Los & van Kemenade Reference Komen, Los and van Kemenade2023)

The first distinction is between NPs with and without antecedents, i.e. linked or unlinked. If unlinked, the model allows for a category inert for NPs that do not in fact refer to or introduce a referent, as they function as attributes of other entities (like a doctor in She is a doctor or She trained as a doctor) – they are discursively inert. Inert items are most typically bare nouns. In the context of a historical corpus, we can also think of NPs inside PPs that are in the process of grammaticalization, like cause inside be cause ‘because’, or stead inside in stead ‘instead’ as discursively inert. Any NP that is unlinked but does refer to or introduce a referent is given the status new.

If linked, the model makes a further distinction between referents mentioned or merely implied in the previous discourse. Those with textual antecedents are separated into cases of identity or cases with the status inferred. In cases of identity, the NP and its antecedent refer to the same referent; an example would be þære ‘that’ in (1), referring to flasce ‘bottle’ of the previous discourse. The status inferred is more indirect in that there is no exact match with a previously mentioned referent, but the referent's identity can nevertheless be inferred from an evoked schema – once a car is mentioned, we can talk about the driver; once a house is mentioned, we can talk about the windows, in which case driver and windows would be linked to the earlier mentions of a car and a house, respectively, with the status of the link marked as inferred. This is Prince's category of inferrable. A subtype of inferrable referents are ‘containing inferrables’ (Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981), which can be inferred from information within the same NP they occur in. The NP ðisses cyninges rice ‘this king's reign’ in (14) is an example, since the head noun rice is one of the possible inferences that can be made from the referent ðisses cyninges which has an antecedent in the previous discourse. Referents that cannot be linked to any referent mentioned in the previous discourse, whether with a status of identity or inferred, but have an extra-textual antecedent that can nevertheless be assumed to be in the common ground, are labelled as assumed.

The five statuses as a set (the Pentaset) inform an annotation scheme that minimizes ambiguity and hence promotes inter-rater agreement. The Pentaset-annotation scheme allows for a degree of (semi-)automatic annotation: NPs as subject or object complements can receive the status inert on the basis of their syntactic function; first- and second-person pronouns are always ‘given’ in the situational context of any discourse, so they receive the status assumed. In direct speech within a narrative, however, where they have referents in the discourse outside that direct speech, they will be linked to those referents.

Even in cases where automatic detection of information-structural statuses is not possible, the fact that the annotation scheme is added to a corpus that has already been enriched with syntactic information means that any of Prince's (Reference Prince and Cole1981) categories that are not included in the Pentaset, like her ‘brand new anchored’ versus ‘brand new unanchored’ statuses, can still be retrieved. ‘Brand new unanchored’ refers to cases like ane trywene flascan wines fulle ‘a wooden bottle full of wine’ in (1); in our annotation scheme, flasce will not receive any of the three linked statutes (identity, inferred or assumed) or the inert status, so will be new. The NP contains a postmodifier (wine fulle) but this is not an anchor in the sense of Prince because it will not have received a linked status, either. Prince's ‘brand new anchored’, on the other hand, which would be the status of, for example, guy in her example a guy I work with (Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981: 236) will be retrievable because of the combination of the information statuses (new for guy, identity for I) and its syntactic annotation: guy is anchored because the following postmodifier, the relative clause, contains an anchor (I) with a linked status (identity).

The (semi-)automatic annotation tries to keep any appeal to syntactic function or morphological form to a minimum, because categories cannot be assumed to have the same functionality over time; for instance, demonstrative pronouns double as demonstrative determiners in OE, while these two morphological categories have distinct information-structural functions in PDE (see e.g. Gundel, Hedberg & Zacharsky Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993).

Note that the Pentaset-annotation scheme does not employ information-structural notions like topic, focus or contrastiveness, and does not directly mark a PP as frame-setting or as containing a local anchor. Such notions require manual (as opposed to semi-automatic) annotation, which means that only small samples of text can be investigated. While notions of contrast or emphasis are clearly relevant to charting the development of local anchoring, they are difficult to operationalize in the absence of native-speaker judgements. There is also no (complete) consensus in the literature about how to define these notions; and it has become clear that even where there appears to be a consensus, as in the case of aboutness topics, these can be much more difficult to identify in languages other than PDE; Cook & Bildhauer (Reference Cook, Bildhauer, Dipper and Zinsmeister2011, Reference Cook and Bildhauer2013), for instance, report on annotation experiments of German, where the presence of local anchors and pronominal subjects in the same clause gave annotators two options for ‘topic’, leading to very low inter-rater scores.

The labelled bracketing files of the Penn–Helsinki parsed corpora were converted to xml format, and coreference information was added to the xml corpora. This annotation was done by means of CESAX (Komen Reference Komen2011, Reference Komen, Tyrkkö, Kilpiö, Nevalainen and Rissanen2012, Reference Komen, Mambrini, Passarotti and Sporleder2013), which employs a semi-automatic algorithm to resolve antecedent identity automatically where possible. When in doubt, CESAX asks for user input, offering a pool of potential antecedents, evaluated against a ranked set of constraints. An evaluation of the performance of CESAX is provided in Komen (Reference Komen, Tyrkkö, Kilpiö, Nevalainen and Rissanen2012). CESAX automatically processed 54 per cent of the 3,083 NPs in the LModE text investigated, 5 per cent of which were found to be erroneous.Footnote 2 The human annotator agreed with about 40 per cent of the remaining suggestions, choosing other options for the remaining 60 per cent. The total success rate of the algorithm was 72 per cent (Komen Reference Komen, Tyrkkö, Kilpiö, Nevalainen and Rissanen2012). The vast majority of the main-clause-initial PPs for this study were annotated by two annotators (Los and Komen), and a sample of 1,677 NPs within such PPs for the Early Modern English (EModE) part of the corpus were compared, using CESAX's inter-rater agreement calculator. Cohen's Kappa was 0.86 for antecedent agreement, and 0.95 for referential type agreement, which demonstrates that a consistent annotation was achieved.

Four texts (Herbarium, Lacnunga, Leechdoms and Medicina de quadrupedibus) were excluded because they mostly contain formulaic clause-initial PPs, which function as section headings (‘Against gout:’) and are not a constituent of the following clause.

4 Results

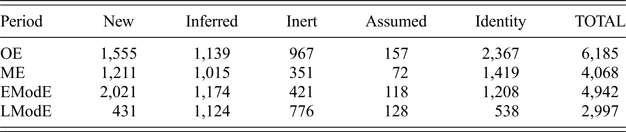

The results of our corpus investigation are given in table 1.Footnote 3

Table 1. The Pentaset status of NPs in main clause-initial PPs

With these high numbers, it is feasible to not just look at the four periods but to drill down to the individual centuries, as in figure 2 – although we need to bear in mind the problems of coverage in the first two subperiods of ME signalled in section 3.

Figure 2. The Pentaset status of NPs in main-clause-initial PPs

For figure 2, we fitted a generalized additive mixed-effects model to the number of prepositional phrases, using a Poisson distribution. We included the following terms (in parentheses, an explanation of how the term contributes to the model): Pentaset (Identity, Inferred, Assumed, Inert, New) as a parametric term (average number of prepositional phrases according to Pentaset), a smooth over century (9th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th) by Pentaset (change in number of prepositional phrases over century by Pentaset) and a by-text factor smooth over century (to account for variations between texts). An offset term was also included to account for the fact that length (in words) differed across texts. The reported estimates are the number of prepositional phrases assuming a text length of 100k words.

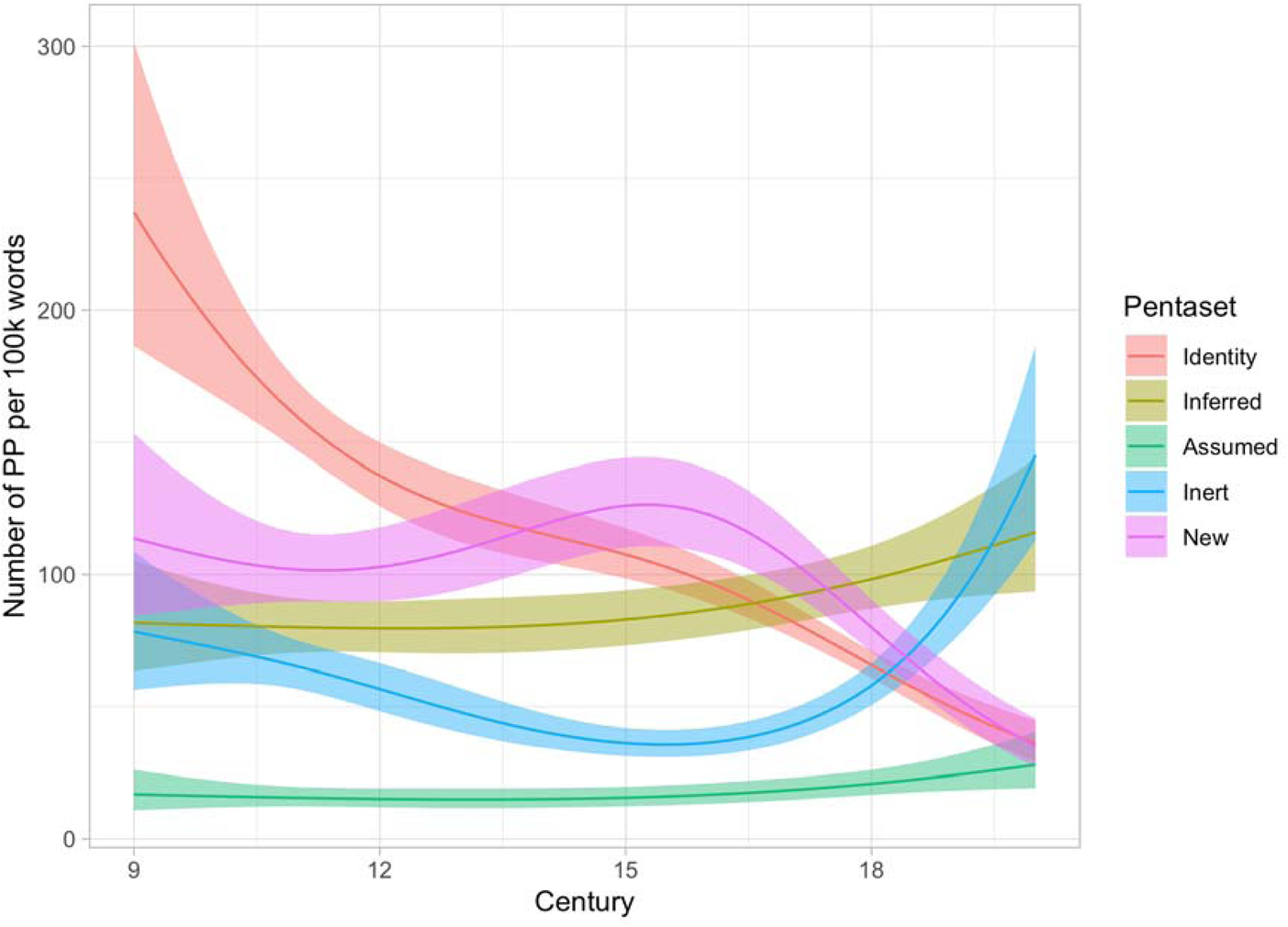

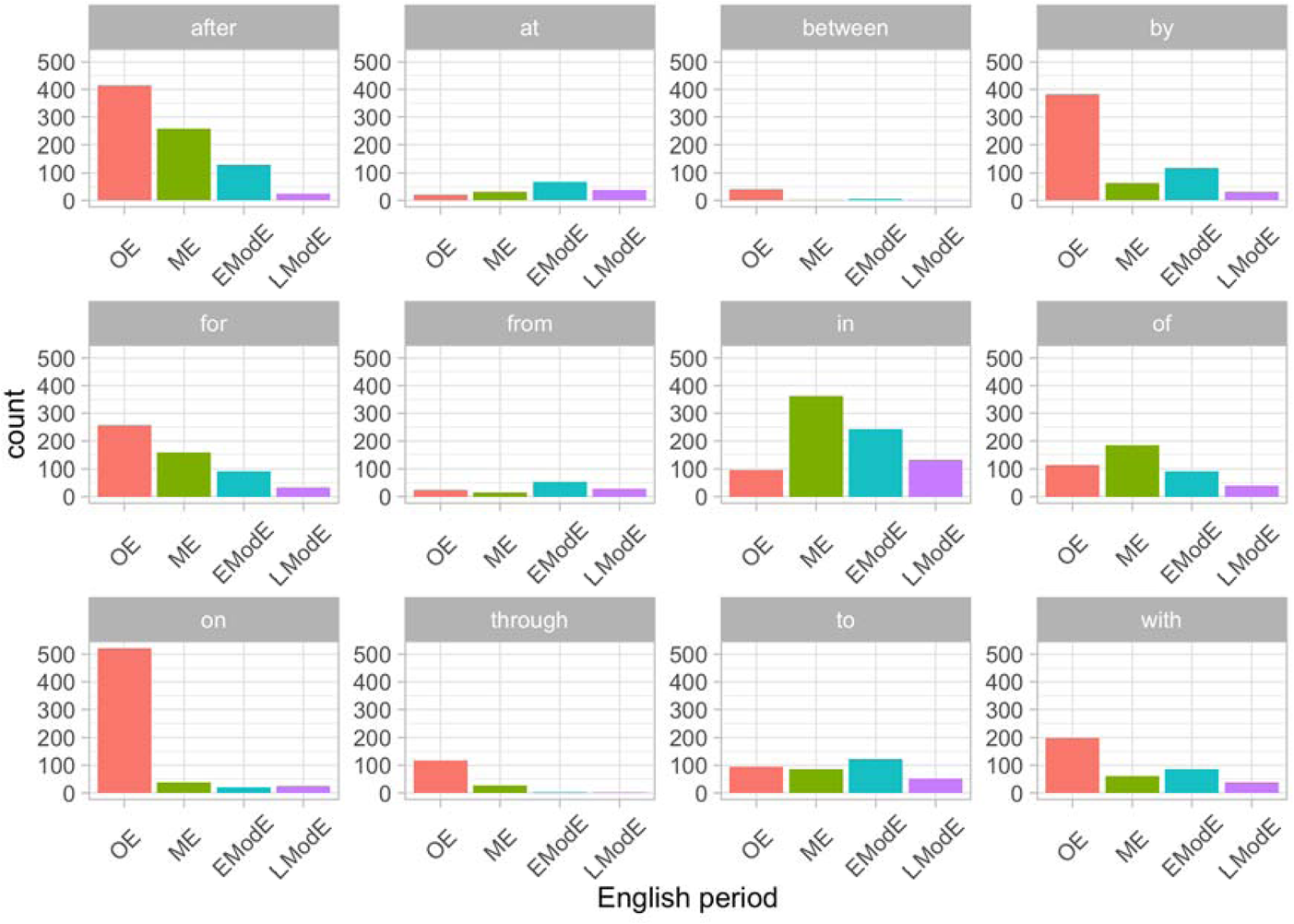

Our hypothesis about the diachronic development predicts a difference in the ratios between ‘given’ NPs (i.e. NPs with Pentaset statuses of identity, inferred and assumed) versus ‘new’ NPs within main-clause-initial PPs between all periods (as the rate of ‘given’ should show a persistent decline from OE onwards). This prediction is borne out for identity, the ‘heartland’ of the local anchor (like Of þære in (1)), as figure 2 shows a clear decline, confirming the hypothesis that main-clause-initial PPs become less referential. The decline is not evenly spread over all prepositions, as figure 3 shows, which contains the twelve most frequent prepositions over time, labelled by their PDE counterparts (so that with also includes OE mid, and in includes OE binnan).

Figure 3. Identity with the most frequent prepositions

Although a more detailed account of the variation must wait until a future investigation, we have a few suggestions for some of the fluctuations found in figure 3. The high rates of on in OE should be regarded in the light of the low rates of in, as a large share of the semantic field of ‘in’ was expressed by on at that period; OE wiþ means ‘against’ rather than ‘with’, but wiþ is rare in clause-initial position (only one instance of identity; twelve further instances with the status new occur in the medical texts that were excluded (Herbarium, Lacnunga, Leechdoms and Medicina de quadrupedibus) because these clause-initial PPs have heading-like functions and are followed by imperative rather than declarative clauses; see the end of section 3); so the majority of the identity-PPs included in the table for ‘with’ contain mid rather than wiþ. The preposition by does not mark ‘demoted’ agents in long passives in OE (which uses fram in this function); for an overview of the development of by, see Cuyckens (Reference Cuyckens, Cuyckens and Radden2002: 262‒3). On inspection, the little bump in EModE for identity with this preposition links up with a finding from another EModE corpus discussed in Los & Lubbers (Reference Los, Lubbers and Petréforthcoming), who note that 1700 appears to be something of a watershed, as the later texts in their corpus observe the flow of given to new information more diligently than the earlier texts, and are more geared to using the long passive in order to manoeuvre new information, expressed in the by-phrase, into clause-final position. In addition to a number of ‘demoted’ agents in clause-initial by-phrases, other items contributing to the EModE bump in figure 3 are of the type exemplified in (15) (by-phrase in bold):

(15) by this letter it appereth how carefull the lord president was to have the rebells thorowly prosecuted (perrott-e2-p1.d.1.p.1.s.138)

The previous context, which is the content of the relevant letter in full, does not contain anything to suggest that by this letter is used contrastively, in terms of evoking alternatives; this is a link to the previous discourse without any special marking, i.e. a proper local anchor, equivalent to a phrasing like this letter shows in PDE.

The category inferred holds its own and even increases slightly; so within the category ‘given’, there is a shift between the proportions of inferred and identity. Inert goes up from EModE onwards, reflecting the higher frequencies of PPs like for example and in faith in EModE, and of PPs like at night, of course, and in fact in LModE. Assumed PPs are a marginal phenomenon in all periods and do not show clear patterns of change through time, perhaps with the exception of a small increase between EModE and LModE.

Figure 2 also shows that the share of new referents gradually increases until EModE. We expect that frame-setters contain mostly new information, and with the decline of local anchors, new referents indeed become more prominent, and constitute a larger share of main-clause-initial PPs. A look at the data shows, however, that the bulge in EModE is largely due to the fact that the corpus contains a number of private diaries that structure their entries around time adverbials, bumping up the numbers of cases with after (after private prayer), at (at noon) and in (in the morning). Two-thirds of all new after-PPs, for instance, are from one particular diary (Diary of Lady Margaret Hoby, 1599–1605). A second factor is that the algorithm for inert looks for bare nouns, so that LModE at last is recognized as an inert PP but EModE at the last is not, nor is in the meane while. Even though some of the data around 1600 are somewhat skewed, the conclusion must be that there was indeed a shift in the information-structural status of the clause-initial adjuncts at least until EModE: they were more likely to encode discourse-links rather than frame-setters in the earlier periods. Ultimately, however, new PPs decline, too.

The hypothesis links the decline of local anchors to the loss of V2 in the fifteenth century, and it predicts a clear and significant decline from ME to EModE, with fewer identity PPs and more inferred and new PPs. However, if V2 was the trigger, the significant decline of local anchors from early ME onwards is unexpected.

5 The functionality of standalone demonstratives

5.1 Introduction

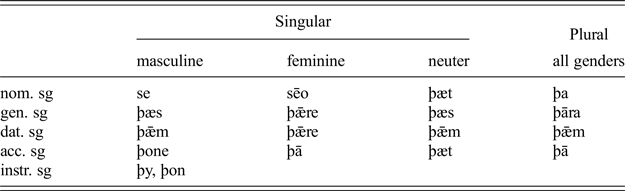

We will turn our attention in this section to the initial decline of local anchoring in the transition from OE to ME, and tentatively link it to the loss of an articulated demonstrative paradigm, which had the dual function of independently used demonstrative pronouns and demonstrative determiners. We will only consider the pronominal use here, and call them ‘standalone demonstratives’ in what follows. The paradigm is given in table 2.

Table 2. The demonstrative paradigm in OE

It is important to note that the paradigm marks case, number and gender. The fact that the demonstrative could be used as an independent pronoun as well as a demonstrative determiner in OE significantly enhanced its referential potential; unlike case, which is determined at the level of the clause, grammatical gender is a stable feature of the noun, and persists from one clause to the next (cf. example (1) above, where flasce ‘bottle’, a feminine noun, is referred to by a standalone feminine demonstrative, two clauses down). The paradigm was lost early on in the transition from OE to ME.

The decline of local anchors is a combination of two factors: the decline of main-clause-initial adjuncts as a means of creating links to the previous discourse, a function that has been taken over by the subject (Los Reference Los, Cuykens, De Smet, Heyvaert and Maekelberghe2018), and a change in the referential functionality of standalone demonstratives (see next section). Standalone demonstratives were ultimately not replaced by an alternative system, although there were contenders (the same, there+preposition, and personal pronouns, particularly the innovative use of (h)it); we will discuss these in section 5.3.

5.2 The antecedents of standalone demonstratives: from NP to stretch of discourse

This section zooms in on two prepositions in our corpus, in and on. In was selected because it is highly frequent in all periods and stable in its semantics, primarily denoting a container; on was selected because of the semantic overlap with in in Old English (see also the brief discussion of figure 3 above).

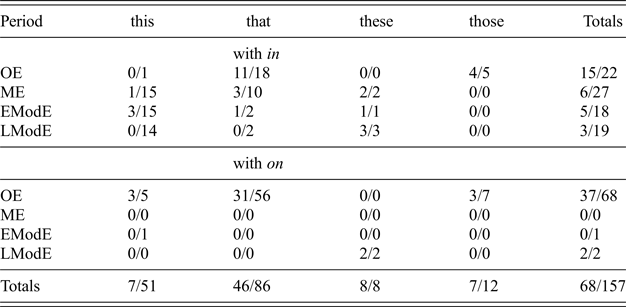

The antecedents of this/these and that/those in a main-clause-initial in-PP shows that there is a dramatic decline in standalone demonstratives with NP antecedents from ME onwards. Table 3 gives the numbers of standalone demonstratives and how many of them are true local anchors.

Table 3. Main-clause-initial in- and on-PPs in the corpus with standalone demonstratives: numbers of local anchors (identity – local – NP antecedent) (before slash) versus total numbers of such PPs (after slash)

The default standalone demonstrative in OE as complement of main-clause-initial in and on is the se demonstrative, whose paradigm we presented in table 2. After OE, the numbers of standalone demonstratives with NP antecedents plummet, even more so if we realize that all the instances of in these in EModE and LModE, as well as one of the two instances in ME, refer to the same biblical sentence, here represented by its LModE incarnation:

(16) Now there is in Jerusalem by the sheep gate a pool, which is called in Hebrew Bethesda, having five porches. In these lay a multitude of them that were sick, blind, halt, withered (erv-new-1881.d.1.p.1.s.331)

The two cases of on these in LModE refer to people, a reminder that the plural standalone demonstrative, unlike the singular, can still refer to human referents in PDE (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1504). The antecedents of the four remaining local anchors proper in EModE, all with in, are presented in (17)–(20) (antecedent and demonstrative in bold):

In ME, there are no examples with on; there are five clear examples with in (if we discard the one instance of a variant of (16)):

The majority of standalone demonstratives in ME, EModE and LModE, however, do not refer to an NP antecedent but to a larger entity; an example is (26) from ME, where ine þet refers to behaving badly in church:

By contrast, the thirty-seven proper local anchors in OE with singular that with in or on refer to places (a dwelling, a province, a camp, a monastery, a church, a vineyard, the Pantheon), but also to an angelic vision, to a sacrifice, to ale, to prayer, to a horse, to a day or a year, and to (a personification of) sorrow. Of the instances where the referent is not local, the reference is to a place (a monastery, an altar), but also to books and to a point made in a debate. Of the plural standalone demonstratives, five refer to groups of people that have just been introduced, analogous to PDE among those, while other single instances refer to candelabras, visions, horses and elephants. The one plural referent that is not local is again a place (churches). The standalone demonstratives that do not have NP antecedents either refer cataphorically (two with this, nine with that), or to a person's conduct or act (like (26)), an event, or to a quoted text.

A second very marked difference between OE on the one hand and ME, EModE and LModE on the other hand is genre; in ME, EModE and LModE, hardly any of the instances of standalone demonstratives occur in narrative texts, while they do in OE. This explanation could be the difference in antecedents: places in OE, and stretches of discourse in the later periods. This ties in with various observations that have been made with respect to PDE versus Modern German texts: in both languages, personal pronouns generally continue existing topics whereas demonstratives are topic shifters, as is demonstrated in (27), from Becher (Reference Becher2010: 1313):

(27) [Modern computers]i can perform [different tasks]k. Theyi / #k /These #i / k . . .

-

(a) # Theyk include mathematical calculations, text processing . . .

-

(b) Thesek include mathematical calculations, text processing . . .

-

(c) Theyi can solve mathematical equations, process textual data . . .

-

(d) # Thesei can solve mathematical equations, process textual data . . .

-

Modern computers and different tasks are both plural, so in theory, they and these could refer to either. Using these, however, most felicitously refers to the new information of the previous sentence, i.e. different tasks, rather than to the subject modern computers, and hence shift the topic from the existing one (the computers) to a new one (different tasks). Where PDE and German (and OE) differ is that German (and OE) can use standalone demonstratives as subjects to topic-shift to a new singular human referent, which PDE cannot do (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1504). Instead, singular standalone demonstratives as subjects in English have developed a clear text-structuring function, where the reference is to the entire previous sentence or stretch of discourse (so an entity of a higher order than a referent) rather than a particular focused constituent. An EModE example from our corpus is (28):

(28) As he [John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester] told me, for five years together he was continually Drunk not all the while under the visible effect of it, but his blood was so inflamed, that he was not in all that time cool enough to be perfectly Master of himself. This led him to say and do many wild and unaccountable things: By this, he said, he had broke the firm constitution of his Health, that seemed so strong, that nothing was too hard for it. (burnetroc-e3-h)

Instead of topic-shifting, singular this ‘rather establishes a new attention focus by shifting the addressee's attention to the state of affairs expressed in the preceding sentence’ (Becher Reference Becher2010: 1312); cf. this in (28), with both instances referring to a period of excessive alcohol consumption, as described in the first sentence.

Even though this textual use of this gives the proximal demonstrative an important, possibly even central role in textual cohesion (Consten et al. Reference Consten, Knees, Schwarz-Friesel, Schwarz-Friesel, Consten and Knees2007: 83), Becher's (Reference Becher2010) comparison of the concluding paragraphs of a number of PDE and German texts of a similar genre shows that demonstratives are nevertheless much more frequent in German than personal pronouns, which is the reverse of the situation in PDE – in PDE, demonstratives connect stretches of discourse, whereas in German, particularly in the form of pronominal adverbs (prepositional phrases built on da ‘there’, like damit ‘with that’; see also the discussion of ME þerfor in (33) below), they connect clauses, using the clause-initial position made available by a V2 syntax.

5.3 Alternatives for standalone demonstratives

If NP antecedents become problematic for singular demonstratives, what alternative expressions are available to restore that functionality? We saw that the referential functionality of a PP like from that in the PDE translation of example (1) could be ameliorated by spelling out the referent: from that bottle. Spelling out the referent, as by this tale in (29), appears as an alternative to the standalone demonstrative in (30).

(29) By this ye may se that he that wyll lerne no good by example |nor good maner to hym shewyd is worthy to be taught with open rebukes. (1526: merrytal-e1-p2 60.16)

(30) By this tale a man may well p~ceyue that they that be brought vp without lernyng or good maner shall never be but rude and bestely all though they haue good naturall wyttys. (1526: merrytal-e1-p1 2.13)

In this particular case, standalone this can also be argued to be referring to a stretch of discourse (i.e. the tale), which means that any reduced functionality is not necessarily a problem here; we find that the ratio of the frequencies of by this versus by this tale introducing the moral of the tale is 11:18 in this text.

An interesting development, and relevant as a potential response to the deficient functionality of standalone demonstratives in PPs, is the emergence of various types of ‘deictic strengtheners’ after ME. One type is the same in (31)–(32):

(31) then you shall make a very strong brine of water and salt, and in the same you shall boile a handfull or two of Saxifrage (markham-e2-p2, 2,116.228-9)

(32) havynge an noneste man with me, whoo had a foreste byll on hys bake, and with the same he cute downe a greate sorte of brakes (mowntayne-e1-h, 211.292-3)

Note that the function of the same is identical to that of a standalone demonstrative in earlier periods – it refers to an NP antecedent.

Another new development that could have replaced standalone demonstratives is pronominal adverbs, like þerfor ‘therefor’ in (33):

The pronominal adverb þerfor ‘for that’ is referential, unlike PDE therefore, and refers back to the clause following the first for (underlined): ‘Because he had excommunicated Anthemius for committing heresy, (for that reason) the emperor exiled and killed him’ or ‘It was because he had excommunicated Anthemius for committing heresy that the emperor exiled and killed him’.Footnote 4 Pronominal adverbs with there are coded as PPs in the corpus and are included in the clause-initial PPs annotated for this study, but they are marginal in terms of frequency and window of emergence and disappearance (end of ME/beginning of EModE).Footnote 5 Neither pronominal adverbs nor the use of the same caught on as a replacement for standalone demonstratives.

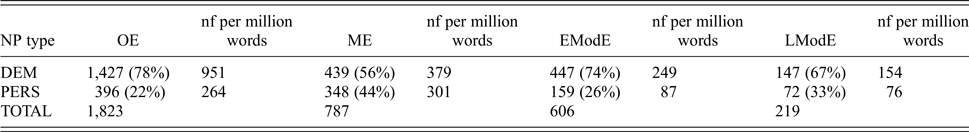

Another alternative to standalone demonstratives that refer to NPs is third-person pronouns, as they are also referring elements with NP antecedents. The share of pronouns (all persons) in the total of local anchors goes up from 22 per cent in OE to 44 per cent in ME (see table 4).

Table 4. Personal and demonstrative pronouns as complement of P in main-clause-initial PPs

Standalone demonstratives decline quite abruptly from OE to ME (from 951 to 379 occurrences per million words) while personal pronouns slightly increase (from 264 to 301 occurrences per million words); after which both standalone demonstratives and personal pronouns decline. In spite of the availability of personal pronouns, table 4 shows that the personal pronouns do not step into the breach left by the loss of standalone demonstratives as local anchors, and cannot be regarded as a strategy to compensate for the local anchoring decline.

Investigating personal pronouns as an alternative to standalone demonstratives does uncover another quirk that aligns OE with modern Dutch and German: the absence of neuter personal pronouns in main-clause-initial PPs. Local anchors in main-clause-initial position in Dutch and German can only contain strong forms of neuter pronouns, which means demonstrative forms. In Dutch, the neuter personal pronoun, which takes the form of a pronominal adverb with er- when the pronoun finds itself in the complement of a preposition, cannot occur there; instead, we get the demonstrative form, a pronominal adverb with proximate hier- (‘here’) or distal daar- (‘there’) (see Broekhuis & Corver Reference Broekhuis and Corver2016: 1249; Travis Reference Travis1984).

Hit is not found as the complement of main-clause-initial prepositions in OE, which is reminiscent of the situation in Dutch and German. The prepositions predominantly govern the dative, the neuter form of which would have been him, but none of the instances of that form in main-clause-initial PPs in the OE part of the corpus refer to non-human referents,Footnote 6 apart from one postposition, & him of afeol ‘(he) him off fell’ (cobede, Bede.4017), where him refers to a horse (a neuter noun), which is not likely to be in Spec,CP (Haeberli Reference Haeberli, Zwart and Abraham2002). Another non-human antecedent picked up by a personal pronoun inside a main-clause-initial PP is one instance of feminine hyre ‘her’ referring to a city: on hyre ne belæfde nane lafe cuce ‘in her not remained anyone alive’ (cootest, Josh 10.28.5480). Prepositions like þurh ‘through’ that govern the accusative are robustly attested with the demonstrative þæt, but not with hit.

(H)it, the neuter nominative/accusative singular personal pronoun, in main-clause-initial PPs represents a ME innovation; the first example in the Parsed Penn–Helsinki Corpora of a main–clause initial PP containing it is c. 1350:

There are six examples of it in local anchors in the fifteenth century, from three texts. The numbers rise slightly in early ME (nine in E1, five in E2 and ten in E3) but never really take off.

Table 4 appears to show that personal pronouns could have emerged as an alternative expression for anaphoric links to NP antecedents after singular demonstratives started to refer to longer stretches of discourse rather than NPs, but this did not halt the decline in the overall numbers of such local anchors. This decline must have been caused by changes in the restrictions on the availability of non-subjects to link to the preceding discourse. The rise of (h)it to express a local anchor may have been triggered by the loss of referential functionality of the demonstrative, but also points to a change in the first position itself, whose close relationship with the demonstrative paradigm – witness its insistence on strong demonstrative forms – and with other deictic elements like then, there and so (see e.g. Los & van Kemenade Reference Los, van Kemenade, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018), broke down in ME.

5.4 In-PPs and the rise of containing inferrables

This section turns to the rise of the category inferred that we saw in figure 2. Within the category of inferred, of particular importance in this rise are ‘containing inferrables’ (Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981; see also above, section 3). Containing inferrables typically contain a possessive pronoun, a demonstrative or a postmodifier (a genitive NP or a PP) linking to a known referent; an example is in ðisses cyninges rice ‘in this king's reign’ in (14) above. In later periods, however, these containing inferrables become increasingly less ‘given’, as their modifiers – typically postmodifiers – make them identifiable from scratch; the determiner the can mark nouns that are new to the discourse, signalling to the reader/hearer that there is a postmodifier that makes that noun identifiable (cf. the money that she had earned over the summer). What we see in the periods after ME is that the link with the previous discourse becomes more tenuous in the category inferred-containing.

Examples of how inferred-containing modifiers can make NPs identifiable are given in (35)–(39) below. The head nouns inside these PP are the near-synonymous place/stead/room, with their modifiers referring to previous holders of certain offices or posts (modifiers in bold):

(35) in his steade sir nicholas bacon, knight, was made lord keepour of the great seale of england, a man of greate diligence and ability in his place, whose goodnesse preserved his greatnesse from suspicion, envye and hate. (EModE, hayward-e2-p1.d.1.p.1.s.46)

(36) in steade of bonner, edmund grindall was made bishopp of london (EModE, hayward-e2-p1.d.1.p.1.s.194)

(37) in the room of the lord chancellor, they would have placed one watson a priest, absurd in humanity and ignorant in divinity. (EModE, raleigh-e2-p1.d.1.p.1.s.73)

(38) In the room of the unwarlike troops of Asia, which had most probably served in the first expedition, a second army was drawn from the veterans and new levies of the Illyrian frontier, and a considerable body of Gothic auxiliaries were taken into the Imperial pay. (LModE, gibbon-1776.d.1.p.1.s.374)

All of these have the status of inferred containing. In (35)‒(36), the link is to the previous discourse; the same is true for (37), but only because the Lord Chancellor happens to be mentioned at some earlier point in this long text; in terms of textual analysis, the NP is primarily identifiable because readers can be assumed to know that their government has such a post. Contrast these examples with (38), from LModE, where the postmodifier is not only much longer, but the link with the previous discourse, the first expedition, is also much more implicit, and requires some effort on the part of the reader to recover. The ‘first expedition’ can be interpreted as the disastrous campaign described in the previous paragraph, but the disaster had not been attributed to the character or provenance of the soldiers but to the climate, the terrain, and other factors, so the unwarlike troops of Asia are ‘new’; nevertheless, the in-PP is inferred containing because a link can be made to this earlier expedition.

One further note can be made about the loss of local anchoring in the context of these inferrables. The PP in (his) steade, as in (35), like some other local anchor-PPs (inside, because, at last), ultimately lexicalized as PDE instead (Tabor & Traugott Reference Tabor, Traugott, Ramat and Hopper1998; Lewis Reference Lewis2011), which no longer requires a modifier – the link with a referent in the previous discourse now has to be recovered from the context by the hearer/reader without the aid of an explicit anaphor: ‘The appearance in the 18th century of instead alone as an adverbial again can be seen as information compression: the replaced item is now ellipted, to be recovered from the context …. The host of the instead in each case is the salient alternative, so that instead without of becomes associated with high information salience’ (Lewis Reference Lewis2011: 427–8). Dutch would require a specific link in the form of a pronominal adverb (in plaats daarvan ‘instead of that’) and German would require a demonstrative pronoun (stattdessen ‘instead-of-that’). Becher's (Reference Becher2010) comparison of textual cohesion strategies in PDE and German texts refers to this phenomenon as ‘explicitation’, and provides further examples: PDE just has involved in a sentence like researchers are still far from working out all the processes involved, where German insists on adding an explicit anaphor: daran beteiligt ‘in that involved’; similarly, PDE would just have a relatively simple example where German has Ein relativ einfaches Beispiel hierfür ‘a relatively simple example of this’ (Becher Reference Becher2010: 1330). Instead has become an adverb in PDE rather than a PP, and hence more acceptable in main clause-initial position.

5.5 Discussion

We can conclude that there is a clear break in the use of standalone demonstratives between OE and ME, long before the loss of V2. In Los & van Kemenade (Reference Los, van Kemenade, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018), we speculate that the loss of the se paradigm and the loss of gender marking are related: grammatical gender allows demonstratives to refer to specific antecedents; of the nominal inflectional categories, gender and number, but not case, facilitate inter-clausal referent-tracking. We saw in section 5 that the singular demonstrative pronouns as local anchor drop in early ME; they are increasingly referring not to NP antecedents but to stretches of discourse. The shift to personal pronouns, particularly to the innovative it, has not led to a recovery, the main reason being the increasing marginality of non-subjects in first position to express links to the previous discourse. It is telling that Hasselgård (Reference Hasselgård2010) only gives half a page to local anchor adjuncts in her monograph on adjuncts in English, and then with examples such as (39) – an adverb with an implicit link (in bold; cf. the discussion of instead in the previous section):

(39) A great cast–iron beam protruded through an opening high up in the building. Inside was the engine – his engine. (W2F–007) (Hasselgård Reference Hasselgård2010: 80)

In Los & van Kemenade (Reference Los, van Kemenade, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018), we speculate that the loss of V2 meant the loss of a multifunctional first position (multifunctional in terms of information-structural status as well as in terms of syntactic function), which worked in tandem with an articulate, gendered, demonstrative pronoun paradigm to enable unmarked links to the immediately preceding discourse. The finer-grained analysis of this article shows that the loss of local anchors started earlier, and its timing suggests that it was due to the loss of that gendered paradigm, and later reinforced by – and possibly kickstarting – the loss of V2. In this light, it is significant that Allen's (Reference Allen2022) data offer concrete support for a link between the loss of gender and the loss of demonstratives as reliable discourse reference trackers (Allen Reference Allen2022: 126–7).

6 Conclusion

This article reports on a study of all main clause-initial PPs in the suite of the syntactically parsed Penn–Helsinki Corpora of OE, ME, EModE and LModE texts. All the NPs within these PPs were annotated with information about the antecedent: whether there was one, and if so, its position in the text; and the status of the link in terms of Pentaset-categories (New, Inert, Assumed, Inferred or Identity), in turn based on Prince's categories (Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981). The aim was to investigate the discourse status of the PP, in particular whether it was a local anchor (referring back to the immediately preceding discourse) or something else, like a frame-setter (forward scoping instead of backward linking). This article has focused on the ‘given’ categories (anchors), reserving frame-setters for future research. Local anchors decline, and there is a shift to personal pronouns instead of demonstratives; the use of the pronoun it in local anchors is an EModE innovation. The hypothesis was that V2 created a slot for a first non-subject constituent that was particularly suited to host local anchors, and that the loss of V2 in the fifteenth century should also mean the end of local anchors. As it turned out, the decline starts earlier, in ME, although the exact timing of the decline may be difficult to pinpoint in view of the M2 data gap. Los & van Kemenade (Reference Los, van Kemenade, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018) speculate that the decline in functionality of the deictic system is a consequence of the loss of a gendered paradigm, and this could also be the cause of the changing frequencies we see in ME. The connection between deictic elements and the first position made available by V2 was broken, and the loss of V2 may have further promoted the decline of local anchors. The unmarked way to establish links to the previous discourse became restricted to the subject.

The decline of local anchors must be considered in the light of the development of new ways to structure discourse in the history of English, after the loss of functionality in deictic expressions and their place in a V2 architecture had compromised earlier strategies to make textual connections. PDE still allows local anchors, albeit at very low frequencies, but with personal pronouns, most notably it, in what appears to be a quite restricted function.

The large-scale study conducted here focused on local anchors, but has also thrown up other questions, particularly about the transition into LModE, which does not continue many of the earlier trends; new main clause-initial PPs – presumably frame-setters – are down, for instance. This and other questions have to be left to future research.