The ancient Maya city of Calakmul was the capital of one of the most powerful Classic Maya kingdoms. At the heart of what became the Snake Kingdom, Calakmul played a pivotal role in the regional politics of the Maya Lowlands during the first millennium AD. Nestled in a riverless, endorheic basin and distant from reliable, year-round sources of potable water while also lacking consistent rainfall, Calakmul relied successfully on complex hydraulic management to feed its residents with adequate amounts of staple crops (Gunn and Folan Reference Gunn, Folan, McIntosh, Tainter and McIntosh2000; Stuart and Stuart Reference Stuart and Stuart2008). This ancient city also relied on extensive trade to obtain additional food and raw materials.

The Calakmul elite, characterized by shifts in spheres of power and far-reaching regional networks, remain poorly understood. Epigraphers have associated the shifts with movements of linguistic/ethnic groups across the Maya lowlands (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Morales López, Heredia, Domínguez Carrasco, Hernández, Josserand, Castillo and Pacheco2010; Josserand Reference Josserand2007; Lacadena and Wichman Reference Lacadena, Wichmann, Tiesler, Cobos and Greene2002, Reference Lacadena, Wichmann, Waters-Rist, Cluney, McNamee and Steinbrenner2005). The stylistic and chemical signature of the majority of local ceramics analyzed by Domínguez Carrasco (Reference Carrasco2008) and Domínguez Carrasco and others (Reference Carrasco, del Rosario, Folan Higgins and Cucina2015) show that they were produced at Calakmul, with copious exchange between Calakmul, Becan, El Mirador, Uaxactun, Tikal, and Barton Ramie during the Early Classic, and between Becan, Calakmul, and El Mirador during the Late Classic.

The location and far-flung political and economic interaction of Calakmul raise questions about the mobility of its residents, along with their food sources and dietary habits. Here we describe and discuss the isotopic evidence from human burials excavated by the Autonomous University of Campeche (CIHS) from 1983 to 1994, including radiocarbon dates; carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in collagen; and strontium, carbon, and oxygen isotope ratios in tooth enamel. These data provide novel information on chronology, water sources, potential places of origin, and child and adult diets of the core population of Calakmul, including two of its rulers.

Calakmul in Perspective

Calakmul lies in the southeastern part of the modern state of Campeche, Mexico, some 35 km north of the Guatemalan border (Figure 1). Decades of systematic survey and excavations at Calakmul, led by William Folan (Autonomous University of Campeche) and Ramón Carrasco (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), have provided detailed information on the urban settlement patterns, architecture, dynastic sequence, artifacts, and buried human remains (Carrasco Reference Carrasco and Guerrero2012; Folan et al. Reference Folan, Fletcher, Hau, Morales López, Domínguez Carrasco, Heredia, Gunn, Tiesler, Mostache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). Although recent decipherments of Maya epigraphy have provided a narrative for the dynastic history and regional interaction (summarized in Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008) of Calakmul, bioarchaeological investigations have put a human face on its urban dwellers (summarized in Tiesler Reference Tiesler and Carrasco2012).

Figure 1. Regional map of the northern Peten, southern Yucatan, and Gulf Coast of Mexico, northern Guatemala, and northern Belize. The colors reflect elevation. The dashed line marks the endorheic basin of the Peten and southern Yucatan Peninsula. The locations of major archaeological sites are marked.

Calakmul dates to the Preclassic and Classic periods (600 BC to AD 900). During the Late Classic (AD 550–830), Calakmul administered a major regional state encompassing an area on the order of 8,000 km2 (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Marcus, Pincemín Deliberos, Domínguez Carrasco, Fletcher and Morales López1995, Reference Folan, Domínguez Carrasco, Gunn, Morales, González, Villanueva, Torrescano and Cucina2013; Marcus Reference Marcus1992, Reference Marcus2003; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). Calakmul was likely one of the largest cities in the Maya region, with a population estimated at approximately 50,000. With some 6,500 structures, the site is huge and covered an area of more than 30 km2 in the middle of the northern Peten rain forest, now protected as a biosphere. Calakmul itself was recently declared a World Heritage site.

Here we report the results of the isotopic investigation of the human remains recovered by the Autonomous University of Campeche in the core of Calakmul (Figure 2). The mortuary treatment documented among these burials includes simple interments, chamber tombs, and sacrificial deposits. These contexts come mostly from excavated structures on and around the Central Plaza, along with Burials Ch-8-1 and Ch-8-2, which were recovered from isolated contexts surrounding the epicenter. A considerable part of this skeletal series (5 of 12 mortuary contexts with status assignment; Table 1) corresponds to richly attired elite tombs that were likely occupied by royalty. At the other extreme are the individuals recovered from probable sacrificial contexts or midden deposits (3 out of 12 mortuary contexts with status assignment; Table 1). This burial population is by no means representative of the whole population of the city, and even less so of the elite of the Snake Kingdom.

Figure 2. Plan of the core of Calakmul (after Folan et al. Reference Folan, Gunn, Domínguez Carrasco, Inomata and Houston2001a). North is up, and each grid unit is 500 m on a side.

Table 1. Sampled Burials, Demographic Data and Isotope Measurements.

Tooth: U = upper, L = Lower, R = right, L = left, M1 = first molar. Age: A = adult, JU: juvenile, I = infant. Sex: M = male, F = female. Status: H = high, M = middle, L= lower, S = sacrifice, PD = special deposit. Period: L = late, T = terminal, E = early, C = Classic, unk = unknown, CH = chultun. Burial number indicates structure in Roman number and the burial number assigned by the project. Sequenced burial numbers assigned at the Bioarchaeology Lab (UADY) appear in parentheses.

The Central Plaza is a large open area that was presumably used for religious, civic, and military activities (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Marcus, Pincemín Deliberos, Domínguez Carrasco, Fletcher and Morales López1995, Reference Folan, Gunn, Domínguez Carrasco, Inomata and Houston2001a). Structure II, its southern platform, was the most voluminous at Calakmul and is one of the largest in the Maya area (Figure 3). Several of the burials sampled for this study came from here: Burials II-1, II-2, II-3, II-5, II-6, and II-7 from Structure II; Burials IIH-1, IIH-2 from Structure IIH; Burials IIB-1, and IIB-2 from Structure IIB; and two unusual deposits (n = 12). Taken together, these crypt-, grave-, and refuse contexts span the Classic period. They contained the human remains of eight adults, three juveniles, and one child. Abundant funerary accouterments were recovered from Structure IIH, where two vaulted tombs were excavated (Folan and Morales López Reference Folan and Morales López1996). One of the individuals included here was an adult who had been cremated in a fleshed state below Stela 114. In all likelihood, this individual had been sacrificed as part of the ritual ceremony involved in resetting an Early Classic Stela (“II-Stela”) at the onset of the Late Classic period (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Marcus, Pincemín Deliberos, Domínguez Carrasco, Fletcher and Morales López1995; Medina Martin and Sánchez Vargas Reference Medina Martin, Sánchez Vargas, Tiesler and Cucina2007). Structure VII closes the Central Plaza in its north. From here we document the tomb of a ruler, also unidentified. Dated to circa AD 750, the large, stuccoed chamber tomb contained the remains of a male ruler who died during his fourth or fifth decade of life (Tiesler Reference Tiesler1999; Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Owen, Aguilar, Arias, Cauich, Folan, Domínguez Carrasco, Lozada and O'Donnabhain2013; see also Lagunas Reference Lagunas1985). The regal accoutrements include a jaguar pelt, a life-sized jadeite mosaic portrait mask, four large jadeite earplugs, a large ik’-shaped jade thorax plaque, and two cheek or lip plugs carved with glyphs.

Figure 3. The Central Plaza at Calakmul with Structures II-VIII. Burial locations shown as black dots (inset, Figure 2).

To the east of the Central Plaza lies Structure III, also called the Lundell Palace, which once served as a central elite residence. Tomb III-5 stands out among the rest of the funerary contexts of Structure III; this spacious, elaborate Early Classic funerary chamber was constructed beneath Room 6 in the center of Structure III and most likely contained the remains of an early, as yet unnamed, ruler of Calakmul. The contents of the tomb included a mat and a variety of textile fragments (Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Owen, Aguilar, Arias, Cauich, Folan, Domínguez Carrasco, Lozada and O'Donnabhain2013; Figure 4). A cloth adorned with hundreds of shells, arranged to form distinct designs, was placed near the deceased, along with other shells carved to represent human skulls. Three pairs of jade earplugs, a jade ring, 32 jade beads, 3 incised jade plaques, 8,252 shell beads, a stingray spine, 5 more elaborate ceramic vessels, and a fragment of a stucco vessel were also in the tomb. Among the offerings, 3 jade mosaic masks stand out: one next to the face, another lying on the chest, and the third at one side of the waist of the deceased (García Vierna Reference García Vierna and Cobos2004; Martínez de Campo Lanz Reference Martínez de Campo Lanz2010).

Figure 4. Artist's reconstruction of Tomb III-5, Structure III, at Calakmul (Sophia Pincemín Deliberos Reference Pincemín Deliberos1994).

The collective study of the above burial series provides information on the residential population, including social status. To characterize social status, we scored burial wealth and architecture in each primary context, using a polythetic set of attributes described in detail elsewhere (Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Tiesler, Cucina, Zabala and Tykot2012:34-35; Tiesler Reference Tiesler1999). For each individual, we also report their chronological association, sex, age at death, and living conditions, following standard procedures and classifications as described in Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994) and Loth and Henneberg (Reference Loth and Henneberg1996). We classified the dental work in the form of filing and inlays according to the taxonomy established originally by Romero (Reference Romero1958; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2000). In the documentation of artificial head modifications, we followed criteria adapted by Romano (Reference Romano1965) and Tiesler (Reference Tiesler2014).

Isotopic Studies

For the purposes of this research, we used several isotopic ratios obtained from bones and teeth. Radiocarbon has been used to obtain dates on bone collagen. In the following pages we first discuss the principles of these methods and known variations in these isotope ratios in the Maya region. The extraction and evaluation procedures for this study are described in detail in published work elsewhere (Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Tiesler, Cucina, Zabala and Tykot2012). In addition to the stable carbon isotopes, radiocarbon ratios were obtained from two diaphyseal samples from Calakmul to obtain direct chronological dates for the analyzed individuals. The calibration of 14C dates, provided in Table 2, converts radiocarbon years to calendar years.

Table 2. Radiocarbon Dates and δ13Ccol Values for Two Samples from Calakmul. LC = Late Classic.

Table Legend: Burial number integrates designation of structure (Roman numbering) and the burial number assigned by the project. Sequential burial numbers assigned at the Bioarchaeology Lab at UAY in Merida appear in parentheses.

Carbon and Nitrogen Isotopes

Nitrogen isotope ratios can reveal the importance of meat in the diet, the role of freshwater fish, and the trophic level of human diets. In this study, carbon isotope ratios were also measured in tooth enamel apatite (δ13Cen). Tooth enamel, and the carbonate and phosphate minerals where carbon is bound, forms during childhood. Thus, while bone collagen provides a record of adult diet, tooth enamel is a record of the diet of early childhood.

Strontium Isotopes

We have measured hundreds of strontium isotope samples from the Maya region, summarized in Figure 5. We obtained specific local baseline data for Calakmul from two archaeological samples of white-tailed deer and three modern samples from snails from the site itself. These values are presented in Table 3 and define a rather tight local range for Calakmul. The five faunal samples have a mean and standard deviation of 0.70776 ± 0.00002, with a range of 0.70775 to 0.70780. Maya centers more than 50 km distant, including Becan and Balamku to the north and Tikal, El Mirador, and Piedras Negras to the south, show average values of 0.708 or greater.

Figure 5. Baseline strontium isotope ratios in the Maya region. Data from Hodell et al. (Reference Hodell, Quinn, Brenner and Kamenov2004), Krueger (Reference Krueger1985), and Price et al. (Reference Price, Burton, Fullagar, Wright, Buikstra and Tiesler2008).

Table 3. Strontium Isotope Ratios for Faunal Samples from Calakmul.

Oxygen Isotopes

In bones and teeth, isotope variation in δ18O due to physiological factors (e.g., perspiration, metabolic rate, urine) averages out, with variation among local populations less than 2‰ (White et al. Reference White, Spence and Longstaffe2002). Oxygen isotopes have been employed in a number of studies in Mesoamerica in recent years (e.g., Spence et al. Reference Spence, White, Longstaffe, Rattray, Law, Ruiz and Pascual2004; White et al. Reference White, Spence, Stuart-Williams and Schwarcz1998, Reference White, Spence, Longstaffe and Law2000, Reference White, Pendergast, Longstaffe and Law2001, Reference White, Spence and Longstaffe2002, Reference White, Spence and Longstaffe2004; Wright and Schwarcz Reference Wright and Schwarcz1998). In addition to the published data, the Laboratory for Archaeological Chemistry has been measuring oxygen isotope ratios in tooth enamel for some time. A summary of these data is presented in Figure 6 for some of the major prehispanic settlements in Mesoamerica. These data are reported as δ18Oap (PDB) in enamel.

Figure 6. Box and whisker plots of δ18Oen (PDB) values from selected Maya sites.

Results

Carbon and Nitrogen Isotopes

Radiocarbon dates were obtained from two bone samples. Burial IIH-2(20) dated to the sixth or seventh century, and Burial VII-1 dated to the late seventh to the ninth century. Information regarding these determinations is provided in Table 2. Both ranges roughly confirm chronology estimates from ceramic wares associated with the burial contexts. What was surprising was the difference in δ13Ccol between the two samples. Burial IIH-2, an adult elite male, has a very high δ13Ccol ratio, typical of maize eaters in the Maya region (e.g., Tykot Reference Tykot and Jakes2002). In contrast, Burial VII-1, the primary high-status burial in Structure VII, has a much lower δ13Ccol ratio of −19.7‰, likely indicating more meat in his diet.

Additionally, carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios were measured in collagen from a series of dentine samples for information on adult diet. A number of such light isotope studies have been done in the Maya region for human remains from the Preclassic through Postclassic periods (e.g., Mansell et al. Reference Mansell, Tykot, Freidel, Dahlin, Ardren, Staller, Tykot and Benz2006; Tykot Reference Tykot and Jakes2002; White Reference White1999). The results of these studies generally point to diets dominated by maize and to some individual differences in terms of less maize and more protein in elite diets. Both carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios were measured on seven samples from Calakmul (Table 1), with a mean δ13Cap of −10.9‰ ± 2.3, and range between −14.5‰ and −7.8‰. These values suggest a maize-dominated diet with a good bit of individual variation. The single bone collagen measurement from the radiocarbon sample of Burial VII-1 was significantly different from these eight individuals; he must have had a diet with less maize or other C4 plants. The eight nitrogen isotope ratios (including one without a carbon companion) average 11.0‰ ± 1.4, with a range of 9.2–13.1. These values for carbon and nitrogen isotopes generally fall within the reported range for Maya burials (Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Tiesler, Cucina, Zabala and Tykot2012; Tykot Reference Tykot and Jakes2002). A scatterplot of δ13C vs. δ15N for these burials from Calakmul shows some correlation of the carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios, resulting in a negative relationship (r = −0.48). The value is not significant, but the trend reflects the relationship between consumption of animal protein and maize in the diet — that is, the more animal protein in the diet, the less maize.

Carbon Isotopes in Tooth Enamel

There are eight samples from Calakmul with apatite carbon measurements. These δ13Cap values range from −8.6‰ to −2.8‰ with a mean of −5.5‰ ± 2.16. There is a significant correlation (at 5%) between the collagen and apatite carbon, r = 0.78, documenting the relationship between childhood and adult diet among the Maya at Calakmul. The offset between the collagen and apatite δ13C values also is of interest. These eight values range between 2.1‰ and 6.7‰, with a mean of 5.4‰ ± 1.5. In general, the offset is greater than 4.4‰ and reflects the importance of maize in the diet. There is only one value less than 4.4‰. Burial IIB-2 was excavated in front of the access area to the earthen altar filling the central southern room of Structure II-B (Coyoc Ramírez Reference Coyoc Ramírez2006:56). It has an offset of 2.1‰, which suggests that meat protein played a significant role in the diet of this individual. If the 6.9‰ offset of Harrison and Katzenberg (Reference Harrison and Katzenberg2003) is used, all of the 13C apatite-collagen values are below 6.9, pointing to an emphasis on maize in the collagen 13C values.

Oxygen Isotopes in Tooth Enamel

Oxygen isotope ratios were measured in the enamel apatite of eight individuals from Calakmul. The δ18O values ranged from −0.1‰ to −2.8‰ with a mean of −1.3‰ ± 0.8. These values are the highest recorded in human samples from the Maya region and correlate well with the more positive surface water values reported from this area (Scherer et al. Reference Scherer, de Carteret and Newman2015). The two δ18O end values in this distribution are −0.1‰ for Burial CH 8-1 and −2.8‰ for Burial II-6. The values between 0‰ and −2‰ are intermediate between those expected from precipitation and consumption of relatively heavy water from aguadas and reservoirs. More specific information on oxygen isotopes in groundwater across Mexico is available from Wassenaar et al. (Reference Wassenaar, Van Wilgenburg, Larson and Hobson2009), who report δ18OSMOW values of −4‰ to −5‰ for the entire Yucatan peninsula, slightly lower in the province of Campeche (the location of Calakmul) with values averaging −3.38‰. Lachniet and Patterson (Reference Lachniet and Patterson2009) analyzed δ18O in surface waters collected from Guatemala and Belize. Values are highest in the area of the central Peten around Calakmul and Tikal, due to evaporation from the lakes. Modern values for surface water in the central and eastern Petén of Guatemala are approximately +3.0‰SMOW, among the highest values in the Maya region. Using the equation δ18Oap(PDB) = 0.610 x δ18O(VSMOW) −0.31, derived from equations of Chenery and others (Reference Chenery, Pashley, Lamb, Sloan and Evans2012), and correcting for the difference in standards, surface water data correspond to approximately +1.5‰ apatite (PDB) values.

Strontium Isotopes in Tooth Enamel

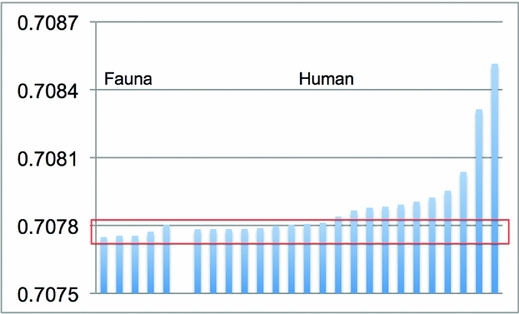

Strontium isotope ratios at Calakmul are of interest for a number of reasons. These values from 22 samples range from 0.70778 to 0.70852, with a mean of 0.7079 ± 0.0002. This, rather surprisingly, is the narrowest range of 87Sr/86Sr values we have recorded at a Maya center. The five faunal samples we measured for baseline bioavailable values also produced a very narrow range, from 0.70775 to 0.70780. The distribution of both faunal and human values is presented in a bar graph in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Bar graph of ranked 87Sr/86Sr for fauna and humans at Calakmul analyzed in this study.

The immediate issue for application of strontium isotope ratios to the burials from Calakmul is the determination of the boundary between local and nonlocal individuals. The very narrow range of values from both the baseline samples and the human remains make this a difficult question. The bar graph in Figure 7 shows three individuals who are distinct from the rest. These individuals are very likely not from Calakmul. The question remains, what about the rest? There is a break in the curve of ranked values in Figure 7 between burials IIH-2 and III-8, that is, at an 87Sr/86Sr value of 0.70825.

What does this break in the line of values represent? Is it local versus nonlocal individuals or simply slightly different sources of food? All five of the baseline values from deer and snails fall within the lower range of ratios, suggesting that the values above 0.70925 may be nonlocal. But again, the overall range of values is very narrow, and some variation in the isotope values of the agricultural fields at the huge site is likely. If food was brought to the site from some distance, this might also be reflected in the 87Sr/86Sr values of some individuals. In sum, because of the narrow range of values within the known range for the Peten, we take a more cautious route and suggest that all of the individuals below 0.708 are local. The three highest 87Sr/86Sr values in the bar graph (above 0.708) indicate individuals who are different from the rest of the samples, with ratios of 0.7081, 0.7083, and 0.7085. These higher values, although distinct at Calakmul, also fall within the known range for the northern Peten and may not indicate a distant origin. The one individual that stands out dramatically in the plot is the female adult from the Terminal Classic: Burial II-6, found in a midden. There seems little question that Burial II-6 moved from some distance to Calakmul. The low δ18O ratio of this individual was noted earlier. The combination of strontium and oxygen ratios indicates a possible place of origin in the Tikal area, perhaps identifying a captive or slave. There was nothing in the grave or location of the burial that would suggest any particular distinction.

Discussion

Isotopic analyses of a series of 22 samples from the Maya site of Calakmul have provided important information regarding the lives of some of its ancient residential population. They point to the maize-dominated diet and predominantly local origin of the upper crust of this closely knit urban center, some of whom were buried in Structures II, III and VII. In the samples available from the CIHS project, we undertook a variety of measurements including radiocarbon dates, carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in collagen, and strontium, carbon, and oxygen isotope ratios in tooth enamel. These measurements provide information on date, diet, and place of origin for the individuals analyzed.

Isotopes and Dynastic Life Histories

Radiocarbon dates were obtained from two bone samples from Calakmul (Table 2). In the case of Burial VII-1, the primary high-status tomb in Structure VII, this date provides a clue regarding the possible identity of its royal occupant. The calibrated BP 2-sigma dates define a range of AD 667–894, a period later than the era of the Snake Kingdom. The golden age of this superpower had come to an abrupt end by then—more precisely in AD 695, when Calakmul and its royal leader Yich'aak’ K'ahk lost a major battle with their old rival Tikal. Theoretically, any of the seven later rulers would fit within this range of radiocarbon years, so this date does not help identify this individual (Marcus Reference Marcus1973; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). Nevertheless, a match with Yuknoom Took' K'awiil seems improbable for reasons of life span. As the inscriptions suggest, Took' K'awiil ruled Calakmul and its hegemony for three decades, from AD 702 to 731 (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). The male adult occupant from the mausoleum in the interior of Structure VII most probably died in his late thirties or forties according to the osteological record (Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Owen, Aguilar, Arias, Cauich, Folan, Domínguez Carrasco, Lozada and O'Donnabhain2013), a number of years that appears too few to accommodate three decades of rule (Grube Reference Grube, Tiesler and Cucina2005). Presumably local, given the 87Sr/86Sr value of Burial VII-1, his low δ13Ccol ratio points to a distinctive diet. Habitual food intake must have been characterized by a non-C4, nonmarine, terrestrial diet with much more protein, likely meat. Such a menu might be explained by a luxurious lifestyle, given his privileged position in authority and his frequent participation in ostentatious feasting.

Collective Isotopic Dietary Information

The collagen nitrogen and carbon isotopic ratios confirmed that the diet of the inhabitants of Calakmul was similar to Maya individuals elsewhere—a combination of plant (mostly maize) and animal foods. Average carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios are plotted for a number of Maya sites in Scherer and others (Reference Scherer, de Carteret and Newman2015:25). Calakmul exhibits the highest δ15N values and a median δ13C value compared to other sites. At the same time there is a general similarity among the majority of the sites in terms of overall diet. The higher nitrogen value at Calakmul may be a reflection of the high proportion of elite individuals sampled in this study.

The Residential Histories of Calakmul

Strontium isotopes provide some information on the place of origin. At Calakmul, a narrow range of values was obtained for the local fauna. The human values are of particular interest in this study because of their narrow range, 0.70778 to 0.70852. In most cases, this range of values would easily fall into the local range of isotopic variation, and nonlocal individuals would not be discernible. There are three individuals (II-2, II-6, and III-1) not from Calakmul, but at the same time likely not from any substantial distance from the site, with the exception of the female Burial II-6 (who may have been a captive or slave). In this case, the combination of strontium and oxygen isotopes point to a person clearly coming from outside the larger region of Calakmul.

Oxygen isotopes provide another perspective on place of origin and are sometimes helpful when combined with strontium data. Figure 8 is a scatterplot of oxygen and strontium isotope ratios from nine individuals at Calakmul. Most of the individuals in this plot fall into a cluster with several pairs (CHII-2 and Est. 2, II-3 and II-7, and III-6 and IIH4). The related burial context of at least one of the pairs (II-3 and II-7) with very similar strontium and oxygen values suggests these individuals may be related or at least grew up in the same or similar households.

Figure 8. Scatterplot of oxygen and strontium isotope ratios from nine individuals at Calakmul.

Oxygen isotope ratios in enamel contain some information on geographic variation due to differences in precipitation and evaporation in the Maya region. Two individuals, II-6 and CH 8-1, were slightly aberrant in a group of largely similar δ18O values. These values are still within the range of variation for a typical population, so the difference may not be meaningful. One question concerns the place of origin for the possible nonlocal individuals identified with strontium isotopes. This question is complicated by the narrow range of 87Sr/86Sr values at the site and the general lack of variation in Sr isotope ratios across the northern and central Peten. As noted above, samples from the nearest major centers to Calakmul have average values between 0.708 and 0.709, e.g., Becan 0.7082, Kohunlich 0.7084, El Mirador 0.7090, Tikal 0.7080. It is certain that some of the lower values from these sites overlap with values from Calakmul. Nonlocal individuals at Calakmul, that is, the three highest 87Sr/86Sr values, could easily be from the region defined by these other centers. At the same time, similar 87Sr/86Sr values can be found across much of the central Peten, making this area also a potential homeland for the nonlocals at Calakmul. It is very unlikely that these individuals came from the northernmost Maya region where ratios are higher, or the southern part of the Peten or the southern highlands of Guatemala where values are lower.

The isotopic results can be considered in conjunction with the observation of permanent body modification in the form of artificial head shapes and dental decorations among the human remains. Ten sufficiently preserved individuals displayed a morphologically altered head form. Four out of the nine artificially shaped heads showed an artificially reclined frame, and the remaining five showed a broad and short shape, without distinguishing any sex or status correlation, as expected (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014). The only trends that stand out are the lack of inlays among the local royals, one rather late (VII-1) and the other one (III-5) rather early in the dynastic sequence, along with the fact that the foreigners with higher strontium ratios all had tabular erect head shapes, a trend that must have set these newcomers visibly apart from the locals with their diverse head shapes and their mostly reclined foreheads.

Conclusions

Used in combination, the isotopes scrutinized in this study provide a powerful means to learn more about the lifestyles and residential histories of the individuals who were buried in the urban core of Calakmul, and to follow broader patterns of population movement, especially given the far-reaching long-distance exchange and political networking at Calakmul (Marcus Reference Marcus1973). During its heyday, the Calakmul sphere of influence was far-reaching and stretched from Copan in Honduras to Palenque in Chiapas and Coba in Quintana Roo. The emblem glyph of Calakmul that appears at so many sites within this sphere is associated with the Kaan dynasty (Flannery Reference Flannery1972; Marcus Reference Marcus1973; Velásquez García Reference Velásquez García and Liendo2008). The presence of the Kaan glyph at Dzibanche before its use at Calakmul suggests that the dynasty may have had its origins further east towards the Caribbean.

In this light, at first glance the results of this study with mostly local signatures may come as a surprise. The relative absence of clearly defined foreigners in Calakmul stands in contrast to other major Mesoamerican centers for which data are available, such as Teotihuacan (Price et al. Reference Price, Manzanilla and Middleton2000), Tikal (Wright Reference Wright2012), Kaminaljuyu (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Burton, Price and Schwarcz2010), and Copan (Price et al. Reference Price, Burton, Sharer, Buikstra, Wright, Traxler and Miller2010). These populations show a much higher variance for 87Sr/86Sr values and a much greater proportion of identifiable nonlocal individuals. Based on the large number of samples we have investigated to date, Calakmul seems to have been inhabited primarily by homebodies; that is to say that Calakmul grew over the centuries with a local population. Nonlocal individuals did not settle at Calakmul in large numbers, or at least they do not appear in our sample. The elites born in the region of Calakmul tended to stay there until political breakup, and a major drought during the ninth century led to political melt-down, out-migration, and abandonment of most of the site (Folan Reference Folan1992a, Reference Folan1992b; Gunn et al. Reference Gunn, Folan, Robichaux and Folan1994, Reference Gunn, Folan and Robichaux1995). Perhaps the fact that Calakmul was a self-sustaining breadbasket in the Peten made it a better place to be.

On a cautionary note, it is important to remember that the burials used in our study come from the elite core of the site and are not representative of the site as a whole. Given the nature of our sample from Calakmul, it is best to be cautious in concluding statements because the individuals we analyzed lived in the center of the site and were largely members of the elite class. When more individuals from a wider area across the site have been investigated, this picture of a rather closed population may change. For the moment, however, Calakmul seems unusual in terms of the general absence of immigrants and the predominance of local individuals in society.

Investigations such as ours raise more questions than they answer. We regard this study as an initial step in the investigation of biographies of the individuals who inhabited the ancient Maya city of Calakmul, and we look forward to broader coverage in this direction. Beyond the historical particularities of the residential histories, the combination of different datasets holds promise for broadening the frames of explanation of past political processes beyond material products.

Acknowledgments

This study received funding from the National Science Foundation. The radiocarbon measurements were conducted at the Arizona AMS Laboratory, the stable C and N isotopes in bone at the Archaeological Science Laboratory of Robert Tycot at the University of South Florida, strontium isotope ratios were measured at the Geochronology and Isotope Geochemistry Lab at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill by Paul Fullagar, and carbon and oxygen in enamel apatite were analyzed by David Dettman of the Environmental Isotope Lab at the University of Arizona. Our sincere thanks go to Geoffrey Braswell and anonymous reviewers of earlier drafts of this work.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data used in this study appear in the article itself or have been previously published in cited materials.