Between 1963 and 1968 the central feature of politics in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) was the monopolization of political power by a divided military. The generals were determined to maintain political control but were consumed by infighting, leading to a succession of coups and attempted coups. In the absence of legal political institutions through which to challenge the successive juntas and as a means of protecting communal, religious, and regional interests, politics frequently took the form of street protests, riots, and rebellions. Many noncommunist civilian politicians and groups believed that the establishment of a legitimate, constitutional, and democratic system with a representative legislature and checks on executive power was the solution to the RVN’s political ills and would stand a stronger chance of resisting the revolution than the military regime. Alongside battles over the RVN’s political institutions, successive regimes and nongovernmental actors attempted to govern, reform, and mobilize. The juntas launched pacification programs and economic reforms and attempted to craft a coalition of support, while civil society groups and nascent political parties attempted grassroots organizing in response to what they perceived as failed government efforts to mobilize the population against the insurgency. Each of these groups had a vision, however limited, for the future of Vietnam that was at odds with that offered by the National Liberation Front (NLF) and Hanoi.

It was only after domestic political turmoil and a noncommunist rebellion against the government, along with pressure from the United States, that the generals acceded to the creation of representative institutions in 1966 and 1967. But the military’s manipulation of the constitution-drafting and electoral processes ensured that such institutions would only graft a thin veneer of legitimacy onto continued military rule and would provide only limited opportunities for competitive politics. General Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu won the 1967 presidential election, consolidated his control of the military, and built a fragile base of support within the new National Assembly. Some political and civil society leaders believed that the RVN’s new institutions provided the best avenue for challenging the military’s continued dominance or for seeking a negotiated settlement with the National Liberation Front. Other noncommunist groups denounced these new institutions as illegitimate and remained outside legislative politics.

In addition to these issues of immediate concern, RVN politics in the mid-1960s was a product of historic faultlines in Vietnamese nationalism. Political identity was sometimes strongly though not exclusively influenced by regional or religious background as well as by differing experiences of colonialism, communism, and the French Indochina War. Many groups were motivated by self-preservation and self-interest and acted in response to their perceived marginalization from power. Confessional and regional identity and historical memory did not wholly determine political action, and political alliances did not fall neatly along these lines, but these divisions contributed to the failure of the RVN’s noncommunists to find a common program and leadership around which to unify, perhaps one means by which the RVN could develop popular legitimacy.

The story of Saigon’s political scene in these years cannot be told without the United States and the RVN’s highly circumscribed sovereignty. Acutely aware of the RVN’s military and economic dependence on the United States, even while extremely sensitive to it, South Vietnamese officials frequently looked to the US Embassy for advice and approval. Through its various agencies in South Vietnam, the United States instigated programs and cajoled, coerced, or bribed RVN officials into action. Deciding that the RVN military was the strongest institution in the country and fearful that a civilian government might be too weak or too independent, the United States backed the generals.

And, yet, US officials repeatedly expressed their frustration at their inability to direct and manipulate South Vietnamese politics to achieve desired outcomes. Many noncommunist Vietnamese believed foreign intervention was necessary to secure an independent, noncommunist Vietnam, if only the foreign supporters would stay in the background. Some objected to and resented American domination of South Vietnam’s political affairs, even as they sought to harness it to their own ends. For others, the costs of American intervention became too great, and they began to support a solution which would include the NLF in the political process and secure an American exit from Vietnam. But opposition to the government did not necessarily mean sympathy for the revolution or opposition to the American presence. All the while, the United States created a screen, in the form of economic and military aid and then conventional military forces, behind which noncommunists fought with one another. As a result, the RVN’s fight against the NLF and North Vietnam frequently took a back seat to the struggle among noncommunists for political control and about the nature of the state and the society they hoped would survive the communist onslaught. Focusing exclusively on the relationship between the United States and the RVN government therefore overlooks an energetic, although highly dysfunctional, noncommunist politics in South Vietnam. The RVN was both an outpost of the American empire and a site of febrile postcolonial politics.

Recent scholarship has cast light on aspects of this topic, including how the legacies of Ngô Đình Diệm’s rule continued to shape the politics of the era and how an authoritarian South Vietnamese state suppressed a vibrant civil society.Footnote 1 But the period between the overthrow of Ngô Đình Diệm in 1963 and the establishment of the Second Republic of Vietnam in 1967 demands further archive-based studies. For decades, orthodox historians complacently argued that the US mission in Vietnam was doomed to fail because of the absence of a legitimate, functioning noncommunist state in the South. Yet those scholars rarely examined South Vietnamese politics in any sustained manner and failed to reveal the dynamics that made the RVN illegitimate and unviable. Just as American policymakers hoped they could win the war while sidelining South Vietnamese, the historiography has sometimes reproduced the imperialist marginalization of South Vietnamese actors from the American war at the time. An exploration of the Phủ Thủ Tướng (Office of the Prime Minister Collection) in National Archives II in Hồ Chí Minh City and the memoirs of RVN personalities would no doubt reveal many new insights to the researcher with the tenacity to examine the most unstable and chaotic period in the RVN’s twenty-year history.

The Military Revolutionary Council: November 1963–January 1964

On November 1, 1963, after months of political unrest, RVN president Ngô Đình Diệm was overthrown by several of his generals in a US-backed coup. The generals appointed a predominantly civilian cabinet but power rested with the newly established Military Revolutionary Council (MRC), composed of twelve generals with Dương Vӑn “Big” Minh as chair. Although the generals won political power, Buddhists and students had led the protests against Diệm, and the president’s downfall had unleashed or reenergized numerous other political forces. Student and Buddhist groups called for a social revolution that would attack poverty and alienation, which they believed had instigated the insurgency. Several of Diệm’s most prominent political opponents emerged from jail or returned from exile, while nationalist political parties that had long clashed with the communists but remained underground during Diệm’s reign began to operate more openly. The MRC and subsequent juntas were compelled to respond to these forces and would struggle variously to court, contain, or suppress them, while crafting a coalition of support.

The most contentious question of the MRC period is whether its leaders planned a “neutral solution” for the RVN. In a series of post facto interviews with the historian George Kahin, former MRC leaders insisted that their plan had been to build a base of support that would allow them to negotiate with the NLF from a position of strength. They believed they could detach noncommunist elements from the NLF, form a government of reconciliation, and allow the NLF to participate in elections. The result would be a neutral country which would secure peace with North Vietnam and reject foreign troops and bases, even while maintaining a military and leaning toward the capitalist bloc. Just as Diệm and his brother Nhu may have been exploring contacts with the North in 1963, Big Minh was in contact with his brother, a colonel in the North Vietnamese army, but there is no evidence that he began negotiations with the NLF.Footnote 2

The MRC made several moves to maintain the support of groups which welcomed Diệm’s downfall. The generals abrogated the Strategic Hamlet Program, the cornerstone of the Diệm regime’s counterinsurgency efforts and the source of much popular resentment in the countryside. To woo civilian politicians, the MRC promised a transition to civilian and constitutional rule and appointed a “Council of Notables” to draw up a new constitution.Footnote 3 This was the first of several bodies which, over the next few years, would act as constitutional conventions or pro tem legislatures. The members of these bodies insisted on a return to civilian and constitutional rule even as they failed to build mass-based political movements and instead attached or reconciled themselves to the military regimes. The generals also released imprisoned Buddhists and students and sanctioned the establishment of a new, independent Student Association and the Unified Buddhist Church.

But these groups placed demands on the new regime. Student organizations supported the establishment of civilian rule and opposed communism, neutralism, and foreign intervention, but were divided along religious and institutional lines.Footnote 4 For the RVN’s politicized monks, the November revolution remained incomplete. Drawing on the ideas of the Buddhist revival dating to the 1920s, these monks and lay leaders were committed to social activism and subscribed to a vision of Vietnamese nationalism based on Buddhist principles that they believed was threatened by foreign ideologies and religions, including communism and Catholicism.Footnote 5 The protests against Diệm showed they were capable of mobilizing thousands of followers in and around South Vietnam’s major cities, though they had less success linking up with Buddhist groups in the Mekong Delta, and the movement itself was factionalized.

By the early 1960s, two monks, Trí Quang and Tâm Châu, led the largest groups. With power bases in Huế and Saigon respectively, the two men briefly united forces against Diệm in the latter half of 1963, but their differences reemerged and widened thereafter. Tâm Châu, whose support rested largely on anticommunist Northern Buddhist émigrés, had a history of cooperation with Catholic organizations against the communists and tended to adopt a more conciliatory stance toward the Southern government. Trí Quang, with a stronger following among younger radical monks and students, has proven harder for scholars to pigeonhole. Some view him as an antiwar activist, committed to ending the conflict by securing the withdrawal of US forces and the establishment of a popularly elected civilian government, followed by negotiations with the National Liberation Front.Footnote 6 Others argue that Trí Quang hoped to channel Buddhist dissatisfaction with Diệm and subsequent military regimes into a mass movement for an anticommunist government based on Buddhist principles.Footnote 7 In the weeks after the coup, Buddhist and student groups demonstrated little opposition to American intervention and insisted instead that the junta purge the government and educational institutions of members of the Cần Lao, Ngô Đình Nhu’s secret political party which had shored up Diệm’s rule and which many viewed as a tool of Catholic repression.

Responding to Buddhist demands, the MRC replaced many officials with ties to the party and, although the depth of the Cần Lao’s influence and its secrecy made a true purge difficult, these moves alarmed some Catholic leaders. While many leftwing Catholics joined calls for a noncommunist social revolution and, eventually, for a coalition government with the NLF, the RVN was also home to more than 600,000 Catholic refugees who had migrated south following the partition in 1954. Many came from Catholic communities that had resisted Việt Minh incursions during the French Indochina War and blamed the communists for their exile. Suspicious of the state and Catholic political parties, including the Cần Lao, these communities often took political guidance from their priests and focused broadly on representing Catholic interests by resisting both communism and the Buddhist domination of RVN politics.Footnote 8

Still, in the weeks following the coup, these groups revealed far more patience with the MRC than they would for subsequent regimes, and the threat to the MRC emerged instead from within the military. American officials had little idea what to expect from the generals once they had removed Diệm, but were alarmed by the junta’s desire to reduce American influence in directing the war. Disgruntled officers, feeling insufficiently rewarded by the MRC, sought to capitalize on this American dissatisfaction and began lining up support for another coup. After I Corps Commander Nguyễn Khánh told his American advisor that he had acquired documentary evidence of MRC generals’ neutralist inclinations, he received word that the United States would not oppose a preemptive coup. The plotters pulled off their plans on January 30, 1964, placing four senior MRC generals under house arrest and retaining the popular Big Minh as a figurehead chief of state. Khánh assumed the role of prime minister and chair of the MRC.Footnote 9 US officials did not instigate the coup, but it is unlikely that Khánh and his associates would have acted without American sanction for fear of losing aid. When presented with the opportunity to remove the suspect generals, American officials chose to stand aside rather than stall Khánh’s plot.

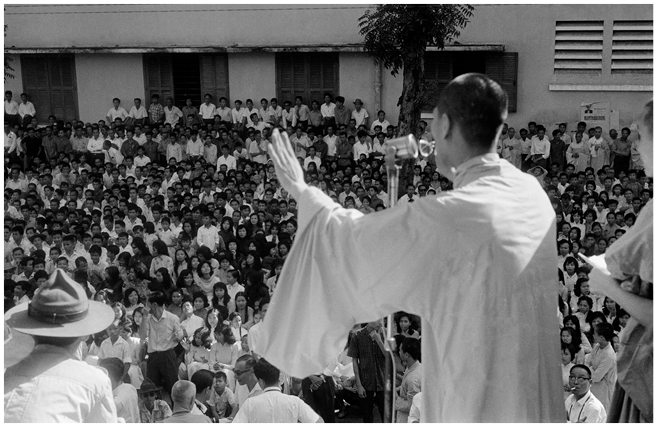

Figure 16.1 A Buddhist monk speaks to the crowd gathered at Saigon’s Xá Lợi Pagoda during memorial services for those who self-immolated to protest policies of President Ngô Đình Diệm (August 18, 1963).

The Rise and Fall of Nguyễn Khánh: January 1964–February 1965

Nguyễn Khánh’s rule marked perhaps the most chaotic period in the RVN’s twenty-year history. He welcomed greater American intervention, and American officials expressed confidence that he would prosecute the war more vigorously than his predecessors. As it turned out, Khánh demonstrated both dependence on and defiance of the United States, and his war leadership revealed itself in bellicose rhetoric about “marching north” rather than in battlefield results. He was highly unpredictable, making and breaking alliances and brutally suppressing some dissent while fleeing from other confrontations. In short, Khánh was an unprincipled opportunist, interested primarily in his own political survival.

Khánh proved incapable of building a base of support among the RVN’s diverse political constituencies. He attempted to win Buddhist favor by repealing a colonial-era decree which denied Buddhism the status of an official religion and by pressing ahead with the trials of several officials of the Diệm regime. These moves did not satisfy Buddhist leaders who wanted a more thoroughgoing purge, but they outraged some Catholic leaders and, throughout 1964, Buddhist and Catholic students took to the streets protesting Khánh’s policies. Meanwhile, Khánh awarded cabinet posts to Đại Việt politicians, the successors of a group of anticommunist, anticolonial parties formed in the late 1930s and with significant support among the officer class. Frustrated with their lack of power, these ministers soon began conspiring to overthrow him.Footnote 10

Khánh believed he could use the escalating war as a pretext for centralizing power and clamping down on his opponents, but his efforts backfired. He seized on the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in early August to impose a state of emergency. He then drew up a new constitution, the so-called Vũng Tàu charter, which granted him practically unlimited powers. This unleashed political turmoil and violence perhaps exceeding that seen during the final months of Diệm’s regime. Students in Saigon, backed by Buddhist leaders, protested the new charter and clashed with counterprotestors, some of whom student leaders believed were bused in from Northern Catholic refugee settlements on the outskirts of Saigon. In the final days of August, sectarian clashes led to several deaths. NLF operatives, having increased their penetration of urban organizations in the spring of 1964, further stoked the flames.Footnote 11 Buddhist and Catholic leaders appealed for calm, but the violence continued for days, indicating the difficulty religious leaders had imposing their will on their followers.Footnote 12

Faced with mounting chaos in the streets and fearful that students and monks could bring him down, Khánh revoked his charter and promised a framework for a new government. He would share leadership of the MRC with two senior generals, while a civilian-led High National Council (HNC) would draft a provisional constitution and ensure the return of civilian rule. But the HNC-appointed prime minister, Trần Vӑn Hương, also proved unacceptable to the Buddhist movement, and protestors again descended on the streets calling for his resignation. The new prime minister’s opponents resented his demand that student and religious groups refrain from political activity, objected to the composition of his cabinet, and condemned his failure to aid the victims of a devastating flood in central Vietnam. Hương imposed martial law in Saigon in mid-November, and dozens of protestors were killed and arrested in clashes that followed.Footnote 13

The balance of political power now shifted to a group of younger military officers or Young Turks, as the American and Vietnamese press would label them. Chief among them was Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, the 35-year-old Northern-born commander of the air force. Khánh had promoted these officers in 1964 to build a power base within the military that would rival senior generals. But the Young Turks gained leverage over Khánh when they rescued him from a Đại Việt–orchestrated coup in September. They demanded that the HNC forcibly retire dozens of senior officers and, when the members refused, the Young Turks dissolved the council. US ambassador Maxwell Taylor denounced the action and continued to back Prime Minister Hương. In response, Khánh publicly condemned Taylor’s interference and, in a volte-face, sought support among Hương’s Buddhist opponents, generating a rupture between the general and his erstwhile American backers. The MRC, now reconstituted as the Armed Forces Council (AFC), resolved the impasse by deposing Hương and exiling Khánh in late January and early February respectively. The AFC appointed the civilian politician Phan Huy Quát as prime minister, and he proved acceptable to the protestors, but the Young Turks were now the principal center of power within the military.

Throughout Khánh’s tenure, officials from the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson and the US Embassy looked on in frustration at the absence of a stable political base from which to escalate the war against the North. Fearful that the Buddhist movement’s success might lead to a neutralist government, US officials supported Khánh and then Hương in their confrontations with the movement, only serving to destabilize RVN politics. With the RVN military effort collapsing, the United States put aside the question of political stability and launched a bombing campaign against the North regardless. Evidently, the Buddhist movement could make or break governments and undermine the foundation upon which the US military effort rested.

American Intervention and the Young Turks, 1965–1966

One area that requires further study is the RVN’s role in the American expansion of the war in the spring and summer of 1965, perhaps the single most significant American violation of RVN sovereignty. Bùi Diệm, Prime Minister Quát’s close advisor and later ambassador to Washington, reported that the American decisions to begin a sustained bombing campaign against the North and dispatch combat troops to the South in February and March were made without consulting Quát’s government. As the number of American deployments grew and their mission expanded in spring 1965, Bùi Diệm said he and Quát felt powerless to oppose these moves. They felt sufficiently ill informed to judge whether South Vietnam was truly on the brink of military collapse and feared that opposition to the Americanization of the war might further threaten government stability during an ongoing cabinet crisis.Footnote 14

The crisis would spell the end of experiments with civilian rule. When Quát attempted to dismiss two ministers for their failure to deal with rice shortages, Chief of State Phan Khắc Sửu refused to sign the decree. He was backed by Southerners and Catholics who had borne the brunt of the arrests in the wake of another failed coup attempt in February and felt Quát’s cabinet was the product of Buddhist and Northern protest and scheming. The crisis dragged on until June and, when Quát requested the generals to mediate, they dispensed with the pretence of civilian rule entirely. The Young Turks established a National Leadership Council, otherwise known as the Directorate, under Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu as de facto chief of state, and a Central Executive Committee, a predominantly civilian cabinet, under Nguyễn Cao Kỳ as de facto prime minister. Thiệu and Kỳ would rule South Vietnam together until 1971, but would fuel their rivalry by building independent power bases within the military and bureaucracy. US officials were taken by surprise by this development but accepted the return to military rule.

Exhibiting a preference for authoritarian governance and military-led development, Kỳ’s “war cabinet” curbed civil liberties and promised to execute speculators and corrupt government officials, instituted austerity measures, and launched rural pacification programs. Opportunities for graft increased as American resources poured in. Supply shortages, inflation, and an artificially low exchange rate created opportunities for speculation, currency manipulation, and capital flight.Footnote 15 Senior officers were frequently implicated in corruption but usually suffered consequences only if their rivals chose to highlight it. Anticorruption efforts were arbitrary. The most egregious example came in March 1966 when Kỳ ordered the execution of the Chinese rice merchant and alleged speculator Tạ Vinh in central Saigon. As former commander of the air force, Kỳ himself reportedly profited from the lucrative heroin trade between Laos and Saigon.Footnote 16

Kỳ’s regime was the first since Diệm’s to pay serious attention to rural pacification. By 1965, the government controlled the cities, towns, and major transport arteries but had lost large areas of the countryside to the NLF. Kỳ established a Ministry for Rural Construction, which charged armed teams with the arduous task of reestablishing local government and carrying out development schemes to win the favor of peasants in newly pacified areas.Footnote 17 Youth groups, Buddhist social welfare organizations, and opposition political parties, already conducting their own pacification programs in the countryside and cities, captured some of these government programs at the local level and used the resources to build grassroots support for future elections.

In the second half of 1965, noncommunist challengers to the regime remained relatively muted. The US government was focused primarily on the military effort and was pleased enough to avoid further turnovers in leadership that it applied little pressure on Kỳ’s government in the field of democratic reform. Nonetheless, the Buddhist movement and even rightwing political parties continued to demand elections.Footnote 18 In late 1965, a rebellion also broke out among US-trained ethnic minority militias in the Central Highlands. Although the government violently suppressed the rebellion, the regime had to make concessions for greater Highlander representation in RVN institutions, foreshadowing a strategy of coercion and concession which the regime would deploy in its next standoff with the Buddhist movement.

The 1966 Buddhist Uprising

The Honolulu Conference in February 1966 set the stage for the RVN’s next political crisis. Recognizing the need for a stable and legitimate RVN government to underpin the American military effort, President Johnson and his advisors used the conference to press the generals into action on economic and political reform. But the summit only reproduced Kỳ’s formula for political development, which Buddhist leaders had already rejected – namely the appointment, rather than election, of a committee to draft a new constitution.Footnote 19 Moreover, Johnson’s endorsement of Kỳ at Honolulu emboldened the latter to move against his principal rival within the junta, General Nguyễn Chánh Thi.

As commander of I Corps in the RVN’s northern provinces, Thi had built up an independent power base, earning goodwill from local Buddhist and student groups through his participation in an aborted 1960 coup against Diệm and by tolerating Buddhist grassroots organizing in his corps area. He criticized Kỳ’s government, spoke out against the overbearing American presence, and refused to attend the Honolulu Conference.Footnote 20 Frustrated and likely threatened by Thi’s independence, and urged on by US ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Kỳ fired Thi in early March. This sparked massive protests throughout the cities in I Corps. The protests revealed a broad range of grievances, from support for Thi to demands for local autonomy, and from anger at the economic turmoil unleashed by the war to calls for Kỳ and Thiệu to resign. NLF activists participated in the protests, though there is little evidence to suggest they directed them.

Trí Quang, the Buddhist monk who had played such a prominent role in the movement against Diệm and enjoyed significant popular support in I Corps, sought to channel this anger into demands for a provisional civilian government, a new constitution, and elections. During the first weeks of the uprising, Trí Quang stressed that he did not oppose the United States’ role in Vietnam, only its manipulation of RVN politics, and even appealed to the Johnson administration to support the Buddhist movement against the generals. Yet the protests took on a growing anti-American tone as they proceeded, as the United States failed to express support for the rebels’ cause and sided openly with the generals.

In his efforts to suppress the movement, Kỳ oscillated between concessions and coercion. The generals sent Thi back to Đà Nẵng to negotiate a settlement, but he claimed he was persuaded by the rebels’ arguments and abandoned his role as mediator. By the end of the month, the central government had lost control of both Đà Nẵng and Huế, as protestors seized the radio stations and weapons depots, and entire army units as well as many local government officials openly sided with what was now called the “Struggle Movement.” The armed supporters of the Vietnamese National Party and Catholic militias now clashed with the struggle forces, even though they also wanted a transition to civilian rule. Kỳ made further proposals for political reform, but none satisfied the protestors. He then announced his determination to retake Đà Nẵng by force, denouncing the rebellious city authorities as communists and suggesting in a press conference that “either the government will fall or the mayor of Đà Nẵng will be shot.” Kỳ flew troops to Đà Nẵng, but backed down in the face of rebel strength and turned his attention instead to splitting the Buddhists by promising the moderate Tâm Châu that he would hold a National Political Congress to discuss elections for a Constituent Assembly. When protestors learned the United States had supplied Kỳ with planes for his Đà Nẵng operation, slogans and graffiti declaring “Down with the CIA” and “Yankees go home!” appeared in towns and cities across central Vietnam.Footnote 21

The regime managed to temporarily subdue the protests in the latter half of April. On April 12, the Directorate withdrew its troops from Đà Nẵng and convened the National Congress in Saigon. Although boycotted by the Buddhist movement, after two days of discussion the representatives made several proposals matching Buddhist demands. Chief of State Thiệu signed a decree that called for the election of a Constituent Assembly within three to five months and the generals’ resignation once it was elected. The demonstrations continued for several days in central Vietnam, but Trí Quang soon concluded that he could achieve his goals through an electoral process if Kỳ kept his word. He called for a temporary pause in the demonstrations and traveled around I Corps requesting Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers to return to their posts.Footnote 22

Kỳ shattered this fragile peace in early May when he said the regime would try to hold elections by October but that he expected to remain in office for another year, until a new government was elected. Huế and Đà Nẵng were soon back under the rebels’ control. Kỳ now resolved to destroy the movement by force, but not before two corps commanders defected rather than carry out the task. Over the course of late May and June, however, government forces retook Đà Nẵng, and Kỳ appointed the ruthless director of National Police, Nguyễn Ngọc Loan, to lead the operation in Huế. After scores of Buddhist movement supporters were killed in these operations and hundreds arrested, the junta announced that elections to the Constituent Assembly would be held in September.Footnote 23

The Buddhist uprising had won concessions at a great cost. The movement was irrevocably divided, and the repression would continue. Throughout the uprising, moderate and radical monks had struggled for control of key Buddhist institutions, with the radicals briefly gaining ascendancy and the moderates eventually attaining the upper hand. Tâm Châu had maintained good relations with the government and at several points urged Buddhists to cease the demonstrations.Footnote 24 In 1967, the government would issue a new charter recognizing Tâm Châu’s faction as an official group. Trí Quang, having once believed it necessary to gain American backing for a Buddhist-led government, was now implacably opposed to both the military regime and the United States. His Ấn Quang movement, itself factionalized, would boycott the Constituent Assembly elections and increasingly call for negotiations with the NLF for a coalition government.

Toward a New Constitution, 1966–1967

The Constituent Assembly produced limited opportunities for political participation by tolerated groups and promised to improve the RVN’s image at home and abroad. But while some hoped it might temper the military’s arbitrary exercise of power, it would in practice serve to legalize and reinforce the status quo of military rule. From the beginning of the electoral process, it was clear that the military would use its power to protect its privileges. The generals insisted that the electoral commission set strict rules for candidacy and, with CIA assistance, General Loan funded the campaigns of Kỳ’s allies. Despite these abuses, the election returned a mixture of religious and regional representatives, including lawyers, academics, businesspeople, and veteran politicians, and even some of the military-funded lists proved more independent than expected, but the generals worked to ensure the production of a constitution favorable to military interests.

Among the most significant political currents within the assembly was Southern opposition to Kỳ and his fellow Northern emigré military officers’ domination of the government. The leader of this tendency was Trần Vӑn Vӑn, a wealthy Southern landowner and veteran anticommunist, who referred to Kỳ as a “neocolonialist.”Footnote 25 Vӑn believed that Southern resistance to Northern domination was a driving force in Vietnamese history and argued that a Southern civilian government could draw on this to resist the communists and split Southern NLF members from Hanoi. Conscious of these charges, Kỳ had expanded his cabinet following the Honolulu Conference to include more Southern civilians and had depended on their support in his battle against the largely central Vietnamese Buddhist movement. They had used these positions to launch local development projects, upon which they built support for their allies’ election to the Constituent Assembly and later to the lower house of the legislature. Evidently ambivalent about General Loan’s use of extreme violence against the Buddhist movement, six Southern cabinet members threatened their resignation when Loan arrested a Southern minister in October 1966 for “North–South discrimination.”Footnote 26 The earliest meetings of the Constituent Assembly occurred against this backdrop. The loosely organized Southern bloc did not represent all of Southern Vietnam, but these Southerners would offer some of the strongest opposition to the regime in the future.

The Constituent Assembly met for the first time on September 27 in the Saigon Opera House. In the words of one deputy, the proceedings often resembled “cheap and ridiculous comedy” more than an opera befitting the setting.Footnote 27 The assembly operated under the watchful eye of the military, with General Thiệu ominously suggesting in his opening address that the Directorate would “lay before [the representatives] all views which we deem useful and constructive.” Assembly debates focused on local autonomy, freedom of religion and the press, private property, and land reform, but above all on the powers of each branch of government. Some delegates expressed support for a parliamentary model. Among those who favored a presidential system, promilitary deputies insisted on a strong executive, while others wanted to embed legislative checks on executive power. Southern deputies tried unsuccessfully to eliminate the 36-year-old Kỳ from the presidential race by proposing a minimum age of 40 for candidacy. The military rejected a draft because it granted too much power to the legislature, and the final version created a presidency with strong powers. But the legislature would not be entirely impotent. With a two-thirds majority vote, the National Assembly could remove from office a president or cabinet member who had served at least a year in office, while an independent inspectorate would investigate cases of corruption at the request of the legislature.Footnote 28

With the constitution promulgated on April 1, the assembly moved on to the contentious issue of an electoral law which would govern the presidential and National Assembly elections in the fall. Southern deputies wanted provisions for a runoff in any presidential election, making it more difficult for a united military to split civilian tickets. But the deputies faced intimidation and threats of physical violence by the military and its supporters. During debates, Loan strutted around the balcony above the deputies, guzzling beer and wielding a pistol. These threats were underscored by speculation that the junta was responsible for the assassination of Trần Vӑn Vӑn and for Deputy Phan Quang Đán’s narrow escape from a car bomb the previous December. The final version of the election law did not include a provision for a runoff and barred candidates who had advocated neutralism or worked directly or indirectly “in the interests of the communism.”Footnote 29

The 1967 Elections, the Tet Offensive, and Thiệu’s Consolidation of Power

American officials were divided about the degree to which the United States should try to shape the outcome of the presidential election. Recognizing that civilian candidates were at a distinct disadvantage against the military, some senior officials in Washington wanted to intervene in the election on the civilians’ behalf. They believed that a civilian victory, although achieved through American intervention, would showcase the legitimacy of the American and RVN war effort. But the US Embassy, at first under Henry Cabot Lodge and then under his successor Ellsworth Bunker, favored stability above all else and pursued a policy that would ensure a military victory.Footnote 30

Even before the new constitution was promulgated, rivals Kỳ and Thiệu began courting military support for their respective candidacies. Loan deployed his police to extort campaign funds from wealthy personalities and swing the vote to Kỳ in unyielding areas. With both men planning to run, American officials were divided as to whom the United States should support but agreed that there should be no joint military ticket. This would deny civilian candidates any chance and would do little to improve the image of the RVN in the United States and internationally. Efforts were made to induce Kỳ or Thiệu to drop out or to encourage them to join a civilian ticket. To resolve the impasse, the Armed Forces Council met in June. The details of the meeting remain unclear but it was finally decided that Kỳ should run as Thiệu’s vice president. After the AFC decision, Kỳ told a CIA contact that he had no intention of relinquishing power, that Thiệu would merely be a figurehead, and that Kỳ would be president in all but name. The generals had drawn up a plan for a “secret military committee” which would continue to guide the government from behind the scenes. It seems that Kỳ, at the very least, expected to have authority to appoint the prime minister and cabinet. With the generals resolved to support a Thiệu–Kỳ ticket, they persuaded promilitary deputies in the provisional National Assembly to eliminate civilian candidates on dubious grounds, including Big Minh, and obstructed the campaigning efforts of others.Footnote 31

Thiệu and Kỳ won a plurality with just 35 percent of the vote. The surprise runner-up was the relatively unknown lawyer Trương Đình Du. Du waited until his candidacy was approved before announcing a peace platform, which included an unconditional bombing halt and talks with Hanoi and the NLF. He won 17 percent of the vote, including a plurality in several provinces west of Saigon, where he earned support among followers of the recently established Tân Đại Việt party, an outgrowth of the more liberal Southern branch of the Đại Việt party that had established grassroots support in the area. Former prime minister Trần Vӑn Hương swept the vote in Saigon where, according to Kỳ’s ally and mayor of Saigon Vӑn Vӑn Của, the election had been honest and probably reflected the electorate’s preferences. Lower house candidate Trần Ngọc Châu reported that a district chief in Kiến Hòa and the Bình Định province chief told him they had manipulated the results to ensure a Thiệu–Kỳ victory. Americans feared that such actions would discredit the entire process. Amid concerns about irregularities, the Constituent Assembly only narrowly approved the election results.Footnote 32

In the senate elections, forty-eight ten-person slates competed for six places. As it was a nationwide race and no slate could claim broad appeal, a minuscule portion of the vote was enough to gain election. This allowed three right-wing Catholic slates to mobilize their loyal grassroots networks to secure half the seats in the senate. Although Ambassador Bunker received approval from Washington to make cash payments to “recruit” candidates for the elections to the lower house, the vote returned more representative deputies. Because of the constituency basis of the election, candidates with the support of locally influential groups could secure election with a small plurality of the vote. The lower house would prove more independent of the government than the senate, a venue in which opposition deputies denounced corruption and misrule. But the elections underscored the fragmentation of noncommunist politics, and the opposition would develop no common political program. As Deputy Trần Ngọc Châu later noted, the new constitution and elections had provided “a façade of democracy masking what was essentially the dictatorship of a military junta (engaged in its own internal power struggle).”Footnote 33

Thiệu’s ascension to the presidency by no means ensured his domination of South Vietnamese politics. For a year after the September 1967 election, Thiệu and Kỳ jostled for supremacy and worked through their aides and supporters to undermine one another’s power. Thiệu at first appeared to uphold his commitment to consult with senior generals on major decisions and acceded to Kỳ’s wishes on the composition of the cabinet. At the same time, however, Thiệu sought to isolate his vice president. Within weeks of the election, Thiệu’s and Kỳ’s staffs occupied opposite wings of the Presidential Palace, and one aide compared crossing the central vestibule to crossing the Bến Hải River, the waterway that divided North and South Vietnam. Kỳ complained to US Embassy officials that, on several occasions, he had attempted to see Thiệu only to be told that he was “sleeping, eating, busy with other visitors etc.” The president had not returned any of his calls.Footnote 34

The Tet Offensive proved a galvanizing event for the RVN. Although North Vietnamese leader Lê Duẩn had expected students to play a key role in the “general uprising,” student leaders called off their protests against the regime and joined the reconstruction effort.Footnote 35 Local self-defense groups sprang up in several towns and cities to protect neighborhoods against communist infiltration, often against the wishes of local government officials. The months after the offensive saw large increases in ARVN volunteers. Some groups now viewed their political survival as dependent on the continued viability of the RVN, including some central Vietnamese Buddhist leaders who were horrified by the communists’ murders in Huế, and now sought to work through the legislature to end government repression against Buddhists. The Vietnamese Confederation of Labor, despite the recent imprisonment of its leaders by General Loan’s police, reconciled itself to the government and enthusiastically embraced training members for civilian militias.Footnote 36

But the new government squandered opportunities to hold this coalition together. American officials implored Thiệu’s government to establish an anticommunist front, which would unite the RVN’s many and fragmented noncommunist constituents. Thiệu’s and Kỳ’s aides proceeded to organize rival groups. In the aftermath of the Tet attacks, Kỳ assumed the most visible role, heading the Recovery Task Force and chairing cabinet meetings to coordinate the government response. Rumors circulated that Kỳ was using the task force to launch a power grab and that a forthcoming constitutional amendment would allow him to assume concurrently the roles of vice president and prime minister. Although Kỳ’s aides were likely responsible for these rumors, Kỳ complained about Thiệu’s “continued, though unfounded suspicions” about the vice president’s plans to overthrow him. Neither the armed forces, Kỳ noted, nor international opinion would tolerate this. Bunker consoled himself that there had, at least, not yet been an “open break” between Thiệu and Kỳ.Footnote 37

The Tet Offensive produced serious anxieties about American intentions. Rumors circulated in Saigon that the offensive was the result of a joint US–North Vietnamese plot, and RVN policymakers feared the beginning of an American deescalation. As Ambassador Bùi Diệm wrote from the embassy in Washington, DC, “it looks like the limits of limited war have been reached.”Footnote 38 Rightwingers in the National Assembly expressed growing concern that the United States would unilaterally negotiate a deal with Hanoi that might include a coalition government with the communists. Throughout 1968, Thiệu adopted a hard line on the peace talks, insisting that they focus only on the cessation of hostilities and not questions of the RVN’s political future. Saigon would not negotiate with the NLF and demanded that Hanoi engage in direct talks with the RVN. In addition, the government increased the size of the military and began to broach the subject of gradual American troop withdrawals. Increased South Vietnamese self-reliance, the new government hoped, would serve as an alternative to a settlement. With improved security after the Tet Offensive, Thiệu tried to bypass the new legislature and instead establish links between the central government and the countryside by devolving to the villages responsibility for governance, defense, and development.Footnote 39

American officials saw Thiệu’s first few months in office and his response to the Tet Offensive as uninspired and lethargic. Kỳ initially appeared to enjoy a surge in power and prestige in the wake of the offensive, but in the following months Thiệu made a series of moves and benefited from several fortuitous events that definitively resolved the power struggle. In March, Thiệu assumed the power to appoint province chiefs, taking this privilege away from the four corps commanders. Under the pretence of an anticorruption drive, he purged chiefs appointed during Kỳ’s premiership and replaced them with loyalists. When Kỳ met with senior generals on March 31 and together they demanded that Thiệu uphold his promise to consult them on important decisions, the president chose not to attend the meeting and pressed ahead. In May, he replaced Kỳ’s chosen prime minister. Kỳ suffered a further diminution in power during the second wave of NLF attacks in May and June 1968. Loan was severely wounded in fighting in May and retired, while several of Kỳ’s closest associates were killed or wounded on June 2 when a US helicopter gunship accidentally fired on a building in which they had gathered in Chợ Lớn. Within weeks, Thiệu had replaced these officials, as well as two more of the corps commanders.Footnote 40 Although Thiệu remained apprehensive about possible coup attempts and even issued coup alerts in September and October, he benefited greatly from the perception among the generals that the United States would not accept any further political instability. By September 1968, Minister of the Interior General Trần Thiện Khiêm reported that the secret military council had collapsed and military leaders had lined up behind Thiệu.Footnote 41

Conclusion

A significantly large constituency of political and military elites accepted the RVN as legitimate, or saw its potential for legitimacy, and were committed to the preservation of a noncommunist Vietnamese state, even if they believed its institutions required reform. But could these groups have rallied around a common program? The diversity of RVN politics and the schisms within regional, religious, and political movements was such that developing a platform that could appeal to all noncommunists presented profound challenges. Military officers, hardline anticommunist politicians, Northern Catholic refugees, moderate noncommunist and antimilitary Southerners, and the followers of the Buddhist revival could all agree on their opposition to a communist takeover but were themselves factionalized and differed in their attitudes to crucial issues such as the extent of military power, the pace and extent of democratic reform, regional and religious representation, the role of the United States in Vietnam, and the degree to which the NLF should be accommodated.

As such, the United States attempted to plug the void of political and military power in South Vietnam. At the heart of this strategy was US support for the South Vietnamese military, which American officials perceived to be the most reliably anticommunist institution. In the absence of noncommunist unity, an authoritarian military-led state took root, one that swung between reform and repression because it was too weak and divided to accommodate or suppress the country’s fissiparous forces. A broad-based and truly representative government might have rallied against the revolution or attempted to maintain popular support by reaching a settlement with the NLF and calling for an American withdrawal, almost certainly leading to further conflict with the military and hardline anticommunist groups.

The RVN was dependent on the United States for its survival, but the success of the American war effort was equally dependent on the emergence and maintenance of a viable and legitimate RVN government. The alternatives – the use of overwhelming military force to compel North Vietnam and the NLF to submit, propping up a deficient South Vietnam indefinitely, or negotiating a political settlement that would preserve an independent South Vietnam – were not politically feasible. The very fact that so many groups in South Vietnam were united in their opposition to communism, if nothing else, convinced some Americans that an adequate anticommunist government might emerge. But the United States could not control political events in South Vietnam, and the likelihood of such an outcome lay in the hands of Vietnamese, not Americans. The dilemma for the United States was that the success of the intervention required political stability but the intervention itself was inherently destabilizing. Not only was the US presence one of the most contentious political issues in the RVN, but US military power also allowed the RVN’s noncommunists to fight among themselves. This may indicate that the war was unwinnable, but not for the reasons frequently posited. Further studies of South Vietnam’s postcolonial politics would therefore do a great deal to explain the failure of the American war effort.