In 1912, two years before the British invasion of Basra during World War I, a young Shiʿi scholar named Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani (1884–1967) departed from the shrine city of Najaf for a twenty-two-month trip through the Persian Gulf, India, and Yemen, spending the bulk of his time in India. The previous winter, he had shuttered the offices of al-ʿIlm (Knowledge), Najaf's first Arabic-language journal, which had run for two years under his editorship. In his travels, he hoped to establish new societies promoting the anticolonial and Islamic revivalist projects that also had been among the journal's missions. His travel diary records him standing on the bow, as he departed from Basra, watching the waves roiling under the ship, which he imagined as a sad metaphor for colonial conquest: “As I watched the water, I imagined that the ship subdued the waves, swaggering as it went, like an empire occupying an enemy country; we see how it humiliates the country's finest people.”Footnote 1 Passing the new refinery of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company at Abadan, he commented on the growing tension between Britain and Germany over the Baghdad railway, ending the passage with a cry: “May God awaken our Iraqi brothers! [ayqaẓ Allāh ikhwānanā al-ʿIrāqiyyīn].”Footnote 2 The call was of course a prescient one, given the importance of both oil and the Baghdad railway to the coming of World War I in general and the British occupation of Ottoman Iraq in particular (Fig. 1).Footnote 3

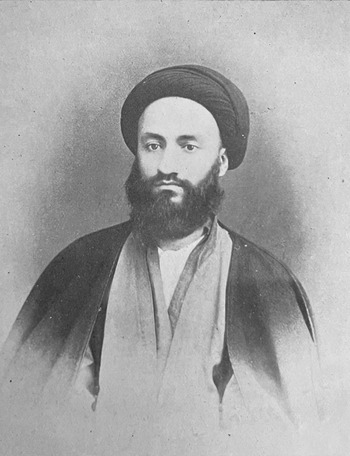

Figure 1. Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani in Muscat, Oman, on his way to India, 1913. Image courtesy of Ismael Taha Aljaberi and Maktabat al-Jawadain al-ʿAmma, Kadhimiya, Iraq.

Later, writing in his diary from India, al-Shahrastani compared his route from Najaf to Calcutta to the similar one traversed almost half a century earlier by the great anticolonial philosopher and Islamic reformer whom he consistently referred to as “Jamal al-Din, known as al-Afghani,” or “Jamal al-Din al-Hamadani, known as al-Afghani,” thereby highlighting the Shiʿi Iranian origins that al-Afghani had taken pains to conceal.Footnote 4 Commenting on these origins, on the philosopher's religious education in Karbala and Najaf, and on his deliberate misrepresentation of himself as a Sunni from Afghanistan, al-Shahrastani reflected on the challenges, “even in this era,” of a Shiʿi thinker such as himself being heard by fellow Sunni Muslims in the Islamic reform movement.Footnote 5 Despite this difference in their willingness to publicly embrace Shiʿism, al-Shahrastani clearly saw his project, including his efforts to establish ties with anticolonial thinkers in India and elsewhere, as a continuation of the anticolonial Islamic revivalist tradition associated with al-Afghani. He reportedly became known in certain circles in India as “Jamal al-Din the Second.”Footnote 6

Al-Shahrastani returned to Najaf a few months before the British invasion of Basra in November 1914. He immediately joined a number of other Shiʿi clerics on the war front in support of the Ottoman call for jihad to defend Iraq, acting as a liaison between Ottoman military commanders and irregular tribal forces; writing letters to Indian Muslim soldiers in the British army that called them to defect from the side of injustice and join the side of truth; and generally offering moral, political, and military guidance to all who would listen and many who did not. When the initial resistance was defeated in 1915, as Ottoman and irregular forces retreated and British forces advanced up the Tigris, al-Shahrastani returned brokenheartedly to Najaf, experiencing the defeat as an “irreparable loss for Islam” (thalama fī al-Islām thalima la yasaddha shayʾ, literally “it opened a gap in Islam that nothing will close”).Footnote 7 Five years later, he played an important role in the great Iraqi thawra (revolt or revolution) of 1920, which posed a major threat to the British occupation and the League of Nations declaration of the British mandate over Iraq. Although it was brutally suppressed by British ground and air forces over a six-month period, the revolt shaped the subsequent course of British governance of Iraq during the mandate years (1920–32). For his involvement, al-Shahrastani was sentenced in a British military tribunal to death by hanging and spent nine months on death row in Hilla before being pardoned in the general amnesty of 1921.Footnote 8

The central debate in scholarship on the 1920 thawra has been over whether it was “truly” or “genuinely” nationalist or instead fueled by local and traditional interests, passions, and attachments.Footnote 9 In both the English- and the Arabic-language literature, nationalism continues to be the primary frame, whether in its presence or absence; nationalism is what authorizes an event in historical time as modern and universal, rather than merely traditional and local. By enclosing the revolt within a particular vision of historical time and its ends, both narratives leave unexplored other kinds of anticolonial resources, networks, and sensibilities that the rebels, including al-Shahrastani and other Shiʿi clerics, might have been drawing on. The tendency in much of the English-language literature to explain away the event as a “tribal uprising” also may help account for the lack of engagement in Iraq studies with recent scholarship on the “Global 1919” moment, or the wave of anticolonial uprisings sweeping across Asia and Africa at the close of World War I.Footnote 10 This absence is especially striking given the significance to both Iraqi and British imperial history of the 1920 revolt, which one British historian has described as “the most serious armed uprising against British rule in the twentieth century,” and which was rehearsed in a major anti-British uprising in Najaf in 1918.Footnote 11

This article traces one strand of the intellectual genealogy of anti-British resistance in the Shiʿi shrine cities by exploring the writings and activities of al-Shahrastani before the war. These include his articles in al-ʿIlm, speeches and essays published in other periodicals, and his diaries from the period, which include drafts of bylaws for Islamic reform societies he hoped to establish.Footnote 12 I make four overall arguments, interwoven throughout the article. First, al-Shahrastani's calls for constitutionalism (mashrūṭiyya or dustūriyya), Islamic reform or revival (islāḥ, nahḍa, tajdīd, iḥyāʾ), Islamic unity or community (al-jāmiʿa al-Islāmiyya), and the ethical cultivation of the self (tahdhīb al-nafs) were all attempts to respond to what he saw as the immediate and existential threat to his world posed by European imperial expansion. The second argument is that al-Shahrastani attempted to mobilize what he called the Islamic social practices (al-sunan al-ijtimāʿiyya al-Islāmiyya) against this threat. Borrowing from his own terminology, I employ the concept of political sociality to gather his attempts to mobilize a variety of social practices and assemblages, including the required religious rituals; new print technologies and constitutionally protected freedoms to use them; social institutions and activities in the shrine cities, such as libraries and majlis gatherings; and Islamic reform associations established to foster all of the above.

Third, al-Shahrastani's conceptions of sociality and the social body, although often resonant with those of the more widely studied Sunni, Christian, and secular reformers of the Nahda (Arabic renaissance), had specificities that I relate to his understandings of subject formation, the sense of impending calamity (in the form of European conquest) in his writings, and the borderlands context of the shrine cities, where governance was shaped by multiple state powers and affiliations. His notions of the “social” did relate to modern changes—print media, constitutionalism, modern schooling, civic associations, etc.—but they were not, prior to World War I, closely affiliated with the nationalist and disciplinary project of a territorial state and were often animated by a temporality of urgency rather than deferral. In contrast to a self-governing or autonomous national subject formed through future-oriented and thus temporally deferring pedagogies, he called for the activation of a heteronomous subject through social bonds and networks organized by Islamic practices. These forms of sociality would breathe the “spirit of Islam” into the social body of the umma and enable it to meet the European threat. On an analytical plane, I propose that more heterogenous understandings of insurgent space and insurgent time—including emergent understandings of thawra or revolution—are revealed when they are not a priori enclosed within the homogeneous space and time of nation–state imaginaries.

Fourth and relatedly, I consider—in a more speculative than conclusive mode—how attending to al-Shahrastani's theorizations of sociality can reveal aspects of the historical emergence of a constitutionalist, revivalist, and later insurgent Shiʿi public in the shrine cities, the sites of coming uprisings in 1915, 1916, and 1918 in addition to the great Iraqi thawra of 1920. With the aim of pointing to areas for further research, I briefly consider modes of this formation in the prewar period, which related to new uses of print media and to existing institutions of libraries and majlis gatherings at least as much as to any theological or political inclinations particular to Shiʿism.

Throughout the article, I engage in a close reading of al-Shahrastani's texts, and do not begin from the assumption that his concepts were simply derivative of either Western thought or the more well-known Sunni reform movements of the Nahda, which developed not only within different Islamic traditions but also in different historical contexts. He did often engage with Sunni reformers such as Muhammad ʿAbduh and his disciple Rashid Rida, and many of his ideas were standard reformist fare for the period. But in addition to placing these thinkers themselves within a Shiʿi political and revivalist genealogy—by regularly reminding his readers of the Shiʿi origins and educational background of ʿAbduh's famous mentor al-Afghani—he also developed some reformist or revivalist concepts in less familiar ways. In arguing that some of these differentiate his thought from that of ʿAbduh, Rida, and other nahḍāwīs, my main interest is not in whether these ideas were or were not unique within the entire Nahda but rather in how they might have related to the sociopolitical context of the shrine cities in the empire's last decade.

The Najafi Nahḍa

Al-Shahrastani was born in 1884 in the Ottoman Shiʿi shrine city of Samarra to a Persian-speaking scholarly family with branches in Iran and Iraq.Footnote 13 In 1903, he moved to Najaf to pursue his advanced studies in the central ḥawza or Shiʿi religious education system. Al-Shahrastani's family and social milieu exemplify the imperial borderland context of the shrine cities. Although histories of Ottoman Iraq often frame the region as a “periphery,” in the world of Twelver Shiʿism Najaf was the center of religious learning and authority by the end of the 19th century, and the other Shiʿi shrine cities located in Ottoman territory (Karbala, Kadhimiya, and Samarra) also were important. These cities sustained and were sustained by religious and economic connections to Shiʿi Muslims in Iran, India, Lebanon, the eastern Arabian peninsula, and elsewhere. Students, pilgrims, corpse-bearers, and other visitors flowed in and out from all parts of the Shiʿi world, and financial gifts fortified links with particular locales abroad. As the Lebanese Shiʿi journal al-ʿIrfan (Knowledge) put it, Najaf was “the city in which the world gathers.”Footnote 14

Rather than view this region as a periphery or frontier, which would center the perspective of a particular state, I conceive of it as a borderland shaped by the interplay of multiple imperial and other state powers and affiliations.Footnote 15 The Ottoman state had a relatively noninterventionist presence in Najaf, which was not only in a peripheral location in relation to Istanbul but also had a “semi-independent” administrative status in recognition of its role as the global center of Shiʿi religious learning and shrine visitation.Footnote 16 The Iranian government also had jurisdiction over some of its affairs, especially regarding the thousands of Iranian students, pilgrims, and permanent residents there at any given moment, and the northern Indian princely state of ʿAwadh provided a significant proportion of the city's revenue, which by the late 19th century was distributed through British colonial agents.Footnote 17

All of these powers played a role in the flourishing of the Ottoman shrine cities as global Shiʿi centers by al-Shahrastani's time. In other words, this was a recent historical phenomenon, not solely attributable to the cities’ religious centrality to Twelver Shiʿism as the sites of the shrines of the most revered Shiʿi Imams. In the 17th and early 18th centuries, during the Safavid era, the Iranian city of Isfahan was the center of Shiʿi learning, and Najaf was “almost in ruin.”Footnote 18 Scholars attribute the 19th-century rise of Najaf and Karbala to a confluence of factors, including the collapse of the Safavid state in the 18th century, which drove many Shiʿi ʿulamaʾ into Ottoman Iraq, along with political, economic, and environmental changes over the course of the 19th century—including the shift in the course of the Euphrates toward the two towns—that contributed to their flourishing as religious, agricultural, and trade centers. Even the fledgling Wahhabi state in Najd had played a role, albeit a negative one. The Wahhabi sack of Karbala in 1802 helped inspire Shiʿi missionary work and conversions among the formerly Sunni tribal communities in southern Iraq, in the interest of defense but with the additional outcome of raising the status of the shrine cities among those communities.Footnote 19

By the turn of the century, the significance of the shrine cities was intensified by the increasingly active political engagement of religious scholars, which related to the above changes as well as to shifts in the dominant schools of Shiʿi thought. The re-ascendance of the rationalist school of Usulism, the emergence of the concept of deputyship (niyāba ʿāmma), and the rise of the institution of supreme exemplar (marjaʿiyyat al-taqlīd) all strengthened the authority of mujtahids to issue fatwas on political questions.Footnote 20 The most well-known manifestation of the “growing trend toward activism in Shiʿi Islam” was the increasing influence of the Ottoman shrine cities on political events in Iran, especially the tobacco boycott movement of 1891–92 and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–11.Footnote 21 The boycott movement was fueled by the fatwas of leading mujtahid Muhammad Hasan Shirazi from Samarra, the hometown of al-Shahrastani, who was around seven at the time.Footnote 22

Shirazi had moved from Najaf to Samarra in 1875, a move that “alarmed” the Ottoman government, since Samarra, although it housed an important Shiʿi shrine, was located north of Baghdad rather than on the Middle Euphrates, and had a predominantly Sunni population.Footnote 23 The government made some effort to stem rising Shiʿi influence there.Footnote 24 But in the other shrine cities, projects to integrate Shiʿi subjects into Ottoman institutions were minimal and largely unsuccessful.Footnote 25 After the Ottoman Constitutional Revolution of 1908, relations between the government and the ʿulamaʾ improved. Several public schools for boys were established in the shrine cities and Shiʿi neighborhoods of Baghdad, which Yitzhak Nakash calls the “beginning of Shiʿi secular education in Iraq.” Although they carried the title “Ottoman,” these schools seem to have been funded by Shiʿi merchants and managed locally rather than by the central government.Footnote 26 They may have been a model for al-Shahrastani when he tried to establish Shiʿi associations from Iraq to India that would run modern schools, as we will see below. In 1910, Ottoman authorities briefly considered closing some Shiʿi religious schools and the Shiʿi personal status courts, which operated outside official Ottoman recognition, and transferring cases in these courts to the Sunni Hanafi courts, but neither idea was pursued.Footnote 27

As with many clerics of his generation, al-Shahrastani's political awakening occurred in the context of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.Footnote 28 While religious actors were not the only leaders of this movement, its religious wing was guided by ʿulamaʾ based in Najaf. Foremost among them was Muhammad Kazim al-Khurasani, the leading Shiʿi mujtahid after Shirazi's death in 1895, who is often described as the spiritual guide of the Iranian constitutional movement.Footnote 29 After al-Shahrastani moved to Najaf in 1903 he became one of al-Khurasani's students.Footnote 30 Over the next few years, the entire Shiʿi clerical class would divide into two camps, the mushrūṭiyyīn (constitutionalists) and the mustabiddīn (literally despots, often translated as anti-constitutionalists).Footnote 31 So central did this divide become to life in the shrine cities that, according to Iraqi sociologist and historian ʿAli al-Wardi, children in the streets played a game called “the constitutionalists and the despots.”Footnote 32 Like other members of the constitutionalist camp, al-Shahrastani supported the Ottoman movement to restore the constitution in 1908, signing telegrams to the sultan and to the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) in Istanbul to that effect.Footnote 33 He also supported the deposing of Muhammad ʿAli Shah by Iranian constitutionalists in 1909, and gave public speeches defending both the Ottoman and Iranian constitutional movements.Footnote 34

In 1910, he established al-ʿIlm, which joined several Persian-language journals that had appeared in Najaf to support the Iranian constitutional movement but was the first Arabic-language journal of this kind.Footnote 35 Like its Persian counterparts, it covered events in Iran and India, and it engaged with reformist journals across the Shiʿi world, such as Habl al-Matin (The Strong Cord) in Calcutta and al-ʿIrfan in Lebanon, founded the year before al-ʿIlm. But it also engaged extensively with the Sunni and Christian Arabic-language press in Egypt and Greater Syria, as well as with events and publications in Istanbul. According to al-Wardi, al-Shahrastani was one of the first two intellectuals in Iraq to become passionate about the publications of the Egyptian Nahda.Footnote 36 He exchanged letters with the famous editor of the Islamic revivalist journal al-Manar (The Lighthouse), Rashid Rida, and on the pages of al-ʿIlm he frequently praised Rida, his Sunni mentor ʿAbduh, and ʿAbduh's mentor “Jamal al-Din al-Hamadani, known as al-Afghani.”Footnote 37 Assertions of the Afghani–ʿAbduh–Rida lineage were common enough in the writings of reformers in this period. But by emphasizing the Shiʿi origins of the first link in the chain, al-Shahrastani made claims to a modern tradition of revival and a political genealogy of Islamic constitutionalism that could be traced not only to Shiʿism but to the ḥawza of the Ottoman shrine cities, where both al-Afghani and al-Shahrastani had studied.

Al-ʿIlm was thus a bridge between the Iranian constitutional movement and the Arabic Nahda, as well as a window onto what we might understand as a specifically Najafi nahḍa. With few exceptions, the borderlands context of the shrine cities has been difficult to see from within the bordered lands of area studies scholarship, contributing to the peripheralization of this Najafi nahḍa in the literature.Footnote 38 In Iran studies, the influence of turn-of-the-century Najafi thought on Iranian constitutionalism is widely recognized, but it is sometimes seen as a temporary phenomenon that relates mainly to the history of Iran and withers away with the death of al-Khurasani and the end of the Constitutional Revolution in 1911.Footnote 39 In studies of the Arabic Nahda, in striking contrast, the assumed political and intellectual conservativism of prewar Najaf often serves as a foil for the emergence of a Shiʿi nahḍa in Lebanon.Footnote 40 In addition to contributing to the intellectual genealogy of anticolonial insurgency in Iraq, then, this article is meant as a contribution to our understanding of Najaf's place in the late Nahda.

The Narrowing of Time

All of al-Shahrastani's public interventions, including the founding of al-ʿIlm, were made in the interest of averting European conquest of what he considered the central Islamic states, the Ottoman and the Iranian, which together he referred to as “our Islamic waṭan [homeland].”Footnote 41 In accordance with the journal's explicitly stated mission to protect that homeland, al-Shahrastani used it to make anticolonial interventions as events unfolded.Footnote 42 For example, he published a fatwa signed by al-Khurasani and others calling for “Muslims of all sects [firaq]” to “strengthen the two Islamic states, the Ottoman and the Iranian, to preserve their rights and protect their independence from the interference of foreigners.”Footnote 43 Another published fatwa opposed the Italian occupation of Ottoman Libya in 1911 and asserted that “the greater the injustice of our enemies becomes, the stronger becomes our unity.”Footnote 44 And a contributor to the journal from Karbala ominously declared: “Time has narrowed [al-waqt qad ḍāq] and the enemy is at the gates; in fact, he is in the house.”Footnote 45

Although the phrase was invoked by a contributor to al-ʿIlm and not al-Shahrastani himself, the sense of a narrowing of time echoes his own frequently expressed predictions of impending calamity. One article warned that Europeans sought to “to annihilate the East and the Muslims together.”Footnote 46 And a statement issued by al-ʿIlm to the Iranian government in 1911—titled “Listen, Iran” and signed by al-Shahrastani and his managing editor ʿAbd al-Husayn al-Azri—cautioned the Iranian government against submitting to Russian and British aggression and demanded that it protect “your sons and your independence and keep the foreigners from your soil—before the day comes (God forbid) when you regret it.”Footnote 47

Adding teeth to these warnings, al-Shahrastani published a text that, according to his analysis of its coded signature, was a long-lost speech of “Jamal al-Din, known as al-Afghani,” whom he described as the “key to the independence movement of the East.”Footnote 48 The speech criticized the European states of al-Afghani's time for their illegal seizure of Algeria, Tunisia, India, Egypt, and other Muslim countries, as well as the despotic government of the Iranian shah Nasir al-Din, whose “insanity” had opened the doors of the calamity that threatened Islam and its ḥawza from every direction.Footnote 49 What will become of us Muslims if “we watch with our own eyes as the Europeans plunder our wealth, violate our rights, and show contempt for our shariʿa?”Footnote 50 The “lands of the Muslims” were in danger, and since it was only possible to remove the danger by removing the shah, it was necessary to remove him, and “replace this merciless and renegade government with a just and legitimate state.”Footnote 51 As is well known, the shah in question, Nasir al-Din (r. 1848–96), was assassinated in 1896 by a follower of al-Afghani. The publication of the speech in al-ʿIlm, moreover, occurred just a year after Muhammad ʿAli Shah was deposed by Iranian constitutionalists in July 1909.Footnote 52

For al-Shahrastani, as for many supporters of the Iranian constitutional movement, opposition to European aggression was necessarily linked to constitutionalism, since governments responsible to their subjects were seen as better able to preserve their sovereignty, whereas despotic governments were vulnerable to corruption.Footnote 53 The speech was followed with a commentary by al-Shahrastani, who noted that al-Afghani, along with the Christian reformer Malkam Khan, had been the “first to place in the hearts of Iran the spirit of the constitution [rūḥ al-dustūr] and to urge the people and their leaders to demand their rights and challenge the despotism [istibdād] of Nasir al-Din Shah.”Footnote 54 This was accomplished through the formation of secret societies, through which al-Afghani “cultivated many souls into his principles” (hadhaba nufūsān kathīratān ʿala mubādīhi)—a comment that foreshadowed al-Shahrastani's later work to establish similar societies from Iraq to India.Footnote 55

In apparently supporting the assassination, al-Shahrastani seems to have taken the right of Muslims to overthrow an unjust government as far as it could go. He addressed the potential charge of promoting anarchy—which in most interpretations of Islam is worse than an unjust government—by making an argument about “the people of Iran,” who only follow their religious leaders, and only when they call on them to act in the name of religion.Footnote 56 By imagining a people united behind their ʿulamaʾ in overthrowing an unjust ruler, al-Shahrastani was able to assert some form of ostensibly popular sovereignty while preserving what Malcolm Kerr called “the political sovereignty of the representatives of the Community, the ahl al-hall wa-l-ʿaqd,” or the religious leaders.Footnote 57 By “political sovereignty,” Kerr meant not the right of the ʿulamaʾ to politically govern but rather their power of decision—according to this interpretation of Islam—to determine when political governance became unjust and to authorize its overthrow. This position, historically a minority one in Islam, was theoretically consistent with that of Rida and ʿAbduh, although in practice perhaps closer to al-Afghani.Footnote 58 As Albert Hourani explains, ʿAbduh famously diverged from al-Afghani on the question of whether the people needed a period of education before they would become “ready for self-government.”Footnote 59 Al-Shahrastani seems to have agreed with al-Afghani rather than ʿAbduh that this period of deferral and education was not necessary or always possible.

Fears of European expansion were ubiquitous in late nahḍāwī writings, but most were not as apocalyptic as those of al-Shahrastani. Indeed, Thomas Philipp has remarked on the striking “general faith in social ‘progress,’” and in the future of the Ottoman state, that prevailed in the writings of most well-known nahḍāwī thinkers all the way up to 1914 and beyond.Footnote 60 He argues that this optimism was nourished by an Enlightenment faith in education and in the role of the intellectuals as the guides of progress. There were of course paradoxes in this relation to political temporality. The “constant suspension of maturity,” as the people were slowly educated into a capacity for self-government, served to legitimize the role of the intellectuals, but it also kept them from “acting as political leaders and mobilizing the masses into the political process.”Footnote 61 Moreover, it would come back to “haunt” them in the interwar period, when the European mandate powers became the “arbiters” of Arab maturity.Footnote 62

In contrast to a linear progressive time in which one works on catching up to the West/the modern by producing subjects worthy of national sovereignty, an impending calamity demands action now. Al-Shahrastani did call for and participate in various pedagogical projects, including schools, as we will see. But these seem to have been closer, at least as he imagined them, to the “secret societies” of revolutionary Iran that helped “cultivate in many souls” the spirit of al-Afghani and the principles of constitutionalism than they were to projects involving the suspension of maturity.Footnote 63 In any case, I submit that his anticolonial project differed from state-led disciplinary interventions to foster the formation of national subjects, which demand deferral of the very political change toward which they often claim to strive.Footnote 64 I will elaborate on this argument in the sections that follow.

Enjoining What Is Right

For several reasons, al-Shahrastani's constitutionalism is not most productively framed as the promotion of “political Westernization,” as Farzaneh has argued of his teacher al-Khurasani.Footnote 65 Al-Shahrastani did link constitutionalism with universal progress, writing that Muslims who believe that Islam is against progress in general, and constitutionalism in particular, are “lazy” and the fault lay with them, not with Islam.Footnote 66 But he rejected the notion that either progress or constitutionalism belonged to the West. He wrote that since the people of Iran would never accept a foreign constitution, it was necessary to educate them into constitutionalist principles on Islamic grounds: “How is it reasonable that a people such as this would rise up on its own and demand a constitution, if they have never heard about it except in foreign clothing?”Footnote 67 That al-Shahrastani called for constitutionalism “in Islamic clothing” does not mean that he was engaged in a derivative discourse or a transparent act of translation, but rather that opposition to despotic government could be articulated from the ground of an Islamic discursive tradition.Footnote 68 More importantly, a focus on translation (e.g., Western “constitutionalism” to Islamic shūra) would miss what was at stake for al-Shahrastani in these arguments.

As with other Islamic constitutionalists, al-Shahrastani invoked the Islamic concept of consultation, shūra or istishāra, of subjects by their rulers, which he asserted had been common in early Islam, before the rulers were seized by despotism: “Justice in government is mandatory and oppression is not permissible, and the ruler's consultation of his nation is a Prophetic practice [istishārat al-amīr qawmahu sunna nabawiyya] ordained by God.”Footnote 69 He linked the practice to Islam's recognition of the “equality of the public,” since “there is no distinction between the rich and the poor, the subject and the ruler” in Islam. He also linked it to the fact that the rulers are responsible for the “money of the Muslims” and for issues connected to war, which concern all.Footnote 70 For the same reasons, “the people are free to demand their rights,” and “free to criticize their rulers; free to command what is good and condemn what is wrong, with their hands, their tongues, and their pens; free to pursue personal benefits or harms, as long as it does not violate the laws,” which are based on the “religion of the country.”Footnote 71

As in these passages, explications of constitutionalism in al-Shahrastani's writings rarely dwelled for long on the concept of shūra. Rather, they regularly returned to the far more universal Islamic obligation of “enjoining what is right and condemning what is wrong” (al-amr bi-l-maʿrūf wa-l-nahī ʿan al-munkar), an obligation clearly referenced—as a “freedom” and a “right”—in the previously quoted passage.Footnote 72 According to a well-known hadith, a wrong may be condemned with the hand, the tongue, or the heart, depending, according to most interpretations, on the position or knowledge of the one doing the correcting.Footnote 73 This hadith also is directly referenced in the passage. Al-Shahrastani was not engaged in a project of reconciling Western and Islamic thought but rather asserting the conditions under which the Islamic obligation of “enjoining what is right” could be nourished as an anticolonial practice in his time. The main condition was its protection within a set of constitutional freedoms or rights accorded to “the people” so that they could use their “tongues and pens” to enjoin and condemn their rulers and one another. The link between freedom of speech and the obligation to enjoin what is right followed a number of other reformers, especially Rida.Footnote 74 And critique as a question of constitutional freedom was a recurring theme on the pages of al-ʿIlm. One article asserted: “The strangest thing I see in this constitutional era in the East is the silence of those who know the truth and the activity of those who do not, even though freedom is not for one type only but for all.”Footnote 75

Knowledge, Nationalism, and a Critique of Mastery

Al-Shahrastani's writings sometimes suggested a universal time of linear progress that was not determined by the West but prefigured in Islam. At other times, nahḍa referred to a cyclical phenomenon, a repeated practice of freeing Islam “from the dead weight of ineffectual and harmful accretions,” which as Samira Haj notes has been the project of Muslim revivalists in all times and places.Footnote 76 Since there was not one but many nahḍas, al-Shahrastani was not necessarily assuming “the existence of a division between two separate eras, and two separate times,” or participating in “the impossible telos of a dream of Nahḍah,” as some scholars have criticized other nahḍāwī thinkers for doing.Footnote 77 This was again not unique to him; it was a sensibility common to all revivalists by definition. The revivalist idea was to undo, through the spread of true knowledge, false customs and traditions. “Using knowledge and our pens, we fight all the forces of corruption, whether in the elderly or the young, the Salafi or the European. . . . We oppose blind rigidity and false traditions . . . whether ancient or modern.”Footnote 78 The journal's title, al-ʿIlm, reflects this preoccupation. The masthead during its first year was adorned on three sides with hadith quotations on this theme: “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim, male and female”; “Acquire knowledge from the cradle to the grave”; and “Seek knowledge even as far as China.”

The knowledge that al-Shahrastani called upon readers to pursue included that of the modern sciences as well as of religious truth; as with other Muslim reformers, the compatibility between the two was a regular theme in his writings. I will not rehearse this well-studied project here. More pertinent to my arguments below is how knowledge was imagined in these texts. Scholars have noted how the power relations and new discursive binaries of colonial modernity—which aligned ignorance/knowledge with tradition/progress, backward/modern, and East/West—altered earlier understandings of knowledge as well as of the subject who pursues it. For example, Stephen Sheehi argues that as knowledge became a “sign of and key to” progress in the 19th century, the “nature of knowledge underwent a transfiguration”; it became something to be “possessed” or “mastered” rather than merely pursued.Footnote 79 Although Sheehi's analysis focuses mainly on the writings of Lebanese Christian nahḍāwīs, he includes several Muslim thinkers, notably al-Afghani and ʿAbduh.Footnote 80 He also insists that these texts were “foundational” to nahḍāwī thought in general, because the dichotomies they delimited—success/failure, presence/lack, progress/backward—were the “epistemological condition endemic to the reform platform of the nineteenth century.”Footnote 81 Common to the discourses of “secular and nonsecular reformers” alike, according to Sheehi, was the production of “an authentic subject who possesses the desire for learning, the will to pursue and acquire knowledge, and the competency and agency to master it.”Footnote 82 This authentic subject was crucially a “national subject,” and an “Arab subject” in particular. Sheehi argues that since the gap between lack and mastery of knowledge was now aligned with the East/West binary, and was simultaneously now internal to the “Arab subject,” endless temporal deferral and thus perpetual failure were endemic to the project.Footnote 83 “It enables a modern Arab subjectivity to be imaginable by permitting the possibility of its presence, while also endlessly deferring this very presence.”Footnote 84

Sheehi's analysis helps to highlight some contrasts between these concepts and those of al-Shahrastani's prewar writings. An “Arab subject” does not appear in the latter, despite the fact that some later histories in Iraq would claim al-Shahrastani as an early Arabist. Nor, in most cases, could the Muslim subject they invoke be described as a national subject or even an “authentic subject” as Sheehi posits it, that is, as the target of a pedagogical project aiming for “autogenetic rejuvenation that needs to arise from the subject himself.”Footnote 85 In al-Shahrastani's revivalist project, an agentive subject is activated by outside forces, not only over time through the slow work of future-oriented pedagogies but also in the present, through the subject's insertion into certain animating social networks. I will elaborate on this in the sections that follow. Here I will just note al-Shahrastani's critiques of claims that knowledge is something to be mastered.

From a number of directions, al-Shahrastani criticized pretensions of mastery, whether expressed in the ambition for total knowledge, an annihilating drive for progress, or colonial domination fueled by nationalist passion. He suggested that the compatibility of Islam and modern science lay not only in their noncontradictory content but also in their methods, including that both established boundaries around what it is possible to know. Similar to how Islam teaches that human reason cannot know the essence and true nature (dhāt wa-kunh) of God but only some of His attributes and signs (ṣifātihi wa-ʿanāwīn dhātihi), modern scientists study the attributes (ṣifāt) of the mind (al-ʿaql) but do not claim to know its essence, any more than they know the essence of the spirit, of electrical power, or of the ether. “The door to knowledge of the essence is closed to all beings, but the door to knowledge through the face and the attributes is open” (bāb mʿarifat al-dhāt masdūda ʿala kāfat al-kāʾināt wa-bāb al-mʿarifat bi-l-wajh wa-l-ṣifa maftūḥ).Footnote 86

The often brutal drive for progress, exemplified in European colonial domination, was related to a failure to respect the boundaries of true knowledge. Although civilization (al-tamaddun) had given humans more knowledge, he wrote, they had used it in immoral ways, for example to develop weaponry with which to annihilate their fellow humans (fī halāk akhwātihi wa-itlāf abnāʾ nawʿihi) “in the name of reform and the establishment of order,” charging forward with “savage vitality under the guise of perfecting civilization [bi-ḥayawiyyat al-hamajiyya bi-zay takmīl al-madaniyya].”Footnote 87 A similar analysis was the grounds of his criticism of strong forms of nationalism, especially the “nationalist fanaticism” (al-ʿaṣabiyya al-waṭaniyya) of European countries, a phenomenon he considered ironic given the unending European critiques of Eastern fanaticism. In an article entitled “Are We the Fanatics, or Are You?” he argued that “fanaticism is a type of aggression against the truth or injustice against reality.”Footnote 88 It is to “operate beyond the bounds of what is necessary for knowledge or faith,” whether through stubbornness or ignorance. In its nationalist form, it accompanies aggression “against innocent creatures,” such as the “aggression of the English against the Indians and the Egyptians, or the aggression of the Russians against the Persians.” The opposite of fanaticism is tolerance, which means “working within the minimum that knowledge and faith require.”Footnote 89 These critiques of exceeding the bounds of necessary knowledge provide context for his advocacy of constitutionalism both as the setting of limits on despotic power and as the fostering of public critique, or enjoining what is right and condemning what is wrong.

The Islamic Social Practices

An article published in al-ʿIlm asserted that merely mentioning the term al-jāmiʿa al-Islāmiyya was enough to “terrify the Europeans,” and it was “what we must grasp and strive to achieve.”Footnote 90 This term is often translated as either “Islamic unity” or “pan-Islamism,” but it also carries the meaning of Islamic association, assembly, community, or gathering. Al-jāmiʿa is the active participle of the verbal root j-m-ʿ, meaning to gather or bring together. In the writings of al-Shahrastani (and many others), the term did not carry the ideological connotation of the English “ism,” nor did it evoke an essentialized national identity, as arguably suggested by the “pan-.”

Even more important to al-Shahrastani's thought, and occurring much more often in his writings, was al-ijtimāʿ, a verbal noun meaning gathering or coming together, from the same root as al-jāmiʿa. He first achieved public recognition a year before launching al-ʿIlm for an exposition of al-ijtimāʿ and its importance to the struggle against European expansion. The context was a speech he gave several times in Najaf in 1909, including at a school in response to the Russian invasion of Iran that year and at an event organized by the local CUP responding to British aggression in Iran.Footnote 91 The speech was translated into several languages and published in numerous venues, including the Ottoman journal Hikmet (Wisdom) in Istanbul and the well-known Persian reformist journal in Calcutta, Habl al-Matin. Footnote 92 Later, it would be reprinted in al-ʿIlm.

The speech began: “Through community [or ‘by gathering together,’ bi-l-ijtimāʿ] we identify the disease, and through community we treat it.”Footnote 93 This phrase was repeated poetically in slightly different ways throughout the speech, which celebrated what al-Shahrastani called the Islamic social practices (al-sunan al-ijtimāʿiyya al-Islāmiyya)—simultaneous prayer, Friday mosque gatherings, and the pilgrimage to Mecca—and called for their mobilization against the European threat.Footnote 94 He argued that these practices had similar effects, within ever widening social formations. The obligation to pray at specific times of the day unites individual believers, reminding “the negligent to think about any injury, disease, poverty, or tribulation befalling his brother and to help him.”Footnote 95 At Friday mosque gatherings, the community comes to know who is afflicted and who is well, so that the strong can “restore the legitimate rights” of the weak: “Through community, the afflicted are recognized, and through community the affliction is removed.”Footnote 96 The pilgrimage to Mecca extends the circle of community wider, as each people (shaʿb) takes from the others some “fortune it had lost,” thus renewing the “great and indescribable spirit” of Islam.Footnote 97 By gathering together at the birthplace of their Prophet, “all of the Islamic peoples” become aware of themselves as “members of a great social body [juththa ijtimāʿiyya ʿaẓīma]; if one member is afflicted, the others will be set into motion to treat [the afflicted one],” just as when an individual is afflicted the practices of collective prayer and mosque gatherings set others into motion to come to his aid.Footnote 98 “Through community, the umma is revived, and through community its troubles are removed.”Footnote 99

The reference to the umma as a “social body” resonates with similar figures in other nahḍāwī writings, but al-Shahrastani used an atypical noun, namely juththa, which can mean body but is more commonly used to mean corpse.Footnote 100 Most writers, and al-Shahrastani in some of his other writings, preferred al-hayʾa al-ijtimāʿiyya, social body/structure/association. The latter term is often translated as “society” and is sometimes seen as a bridge between earlier Islamic understandings of al-ijtimāʿ and the crystallization of the concept of national-territorial society in the word al-mutjamaʿ by the 1930s. With al-juththa, in contrast, al-Shahrastani evokes a mere body, certainly not a “self-regenerating, living organism,” as Ilham Khuri-Makdisi describes al-hayʾa al-ijtimāʿiyya in other Nahda writings.Footnote 101 But al-juththa is consistent with al-Shahrastani's descriptions of the umma as the body into which is breathed the “spirit of Islam.”Footnote 102 This breathing happens specifically through al-ijtimāʿ, the gathering together that sets the body into motion. “Through community, the umma is brought to life” (bi-l-ijtimāʿ taḥya al-umma).Footnote 103

In these texts, neither al-juththa al-ijtimāʿiyya nor al-hayʾa al-ijtimā`ʿiyya evoke the modern understanding of society as an object and of autonomous individuals who exist prior to becoming part of it.Footnote 104 Rather, al-Shahrastani argued that individuals come to exist as moral subjects only in relation to other individuals, and, by analogy, that nations or peoples also exist only in relation to each other (yaʿīsh aqwām bi-l-aqwām kamā yaʿīsh al-fard bi-l-afrād). In this sense—and not in every sense, as I will show below—his conception was closer to earlier Islamic theories, especially those of Ibn Khaldun, of al-ijtimāʿ al-basharī, or human sociability, which posited that “a single human being is dependent upon and thus inseparable from the rest of mankind.”Footnote 105 But this was only what might be called the philosophical or anthropological basis of al-Shahrastani's observations; he was mainly interested in how Islam utilizes this truth by prescribing particular social practices and associations to foster mobilization against a threat.

In thinking about the associational and nonfixed qualities of al-Shahrastani's “social” (ijtimāʿī) it might be useful to recall not only the organicist understandings of sociability of premodern figures such as Ibn Khaldun but also the social theories of postmodern ones such as Bruno Latour, who proposes that we “define the social not as a special domain, a specific realm, or a particular sort of thing, but only as a very particular movement of reassociation and reassembling.”Footnote 106 It is precisely movements of reassociation and reassembling, rather than a specific domain of existence (e.g., the modern “social” as distinct from the political) that al-Shahrastani describes in his call to mobilize the Islamic social practices. I am not suggesting that al-Shahrastani anticipated Latour but rather that we recognize the strangeness and historical particularity of the modern reified notion of the social as a domain or a “sort of thing,” and do not assume that there are only two options for understanding ijtimāʿī: organicist/traditional/Khaldunian or reified/modern/Western.

This might help elucidate how al-Shahrastani differs from Rida. Although Zemmin argues that Rida used al-ijtimāʿ in different ways, he concludes that the main tension was between its meaning as process on the one hand and outcome on the other. As process, it meant “the act of socializing and concurring,” as when Rida referred to “concurring on the beneficial” (bi-l-ijtimāʿ ʿala al-intifāʾ).Footnote 107 As an outcome, al-ijtimāʿ conveyed a social order, and was the “epistemic prerequisite” for the “subsequent and most modern understanding of ‘society’ as a reified entity onto which state and religion could be mapped,” and which ultimately crystallized in al-mujtamaʿ.Footnote 108 The role of the state in Rida's theories seems to account for some of the differences from those of al-Shahrastani.Footnote 109 “Rida defines good works (ṣāliḥāt) as those which rectify the souls of individuals (anfus al-afrād) and the order of social association (niẓām al-ijtimāʿ) in families (buyūt), society (umma), and the state (dawla).”Footnote 110 None of these descriptions evoke al-Shahrastani's emphasis on social practices as the means of mobilizing a community into action against an imminent danger.

The implications of these different conceptions of the social for political temporality are enormous. In al-Shahrastani's understanding, mobilization is at least theoretically possible as soon as the social practices and associations are activated, in contrast to the slow, state-aligned, and politically deferring disciplinary work of producing subjects worthy of the formation and stability of a modern territorial society, Islamic or otherwise. Although the bylaws of his reform societies, examined below, would express some ambivalence on the pedagogical question of temporality, more radical political implications of his theories of social mobilization also run through much of his writing.

The (Public) Cultivation of the Self

Michael Warner writes of the significance, in the modern period, of “the kind of public that comes into being only in relation to texts and their circulation.”Footnote 111 To address such a public—as al-Shahrastani was clearly doing—or to think of oneself as belonging to such a public is “to be a certain kind of person, to inhabit a certain kind of social world, to have at one's disposal certain media and genres, to be motivated by a certain normative horizon, and to speak a certain language ideology. No single history sufficiently explains all the different ways these preconditions come together in practice.”Footnote 112 Publics in Warner's sense are modern, being enabled by modern media technologies and public spheres, but they are not universal or homogeneous; they can only be understood in particular historical contexts and within particular “material conditions of discourse.”Footnote 113

As with the Islamic ritual practices, the value of world-making through print media for al-Shahrastani was to foster Muslims’ capacities to engage in tahdhīb al-nafs (the cultivation of the self) so that they could fulfill their ethical obligations to one another, to the umma, and to God. According to al-Shahrastani, al-ʿIlm was distinguished from other journals by its encouragement of the people to engage in tahdhīb al-nafs.Footnote 114 It did so not only through content exhorting readers to cultivate themselves, which was common enough among revivalist periodicals, but also through projects carried out by the journal's editorial office to “enlighten public thought in Najaf.” Every week “between fifty and 100” newspapers and journals “flood the offices of al-ʿIlm from all directions, in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hindi, and a few in English and French.” After the editors made use of them, these were distributed to “public libraries and reading circles” in Najaf, Karbala, and nearby places. “All of this is from the desire to publicize knowledge [taʿmīm al-maʿārif], bring light to dark thinking, cultivate the rising generation [tahdhīb al-nāshiʾa], replace despotic practices, and liberate the conscience [tahrīr al-wijdān] from the bonds of false traditions.”Footnote 115

Al-ʿIlm played a special role as a vanguard periodical, helping to produce a public of Muslim readers for other periodicals. The journal worked to counter the “aversion toward reading newspapers among the religious leaders of the towns and villages, and among the ascetics, since their view of newspapers improves after they read our humble paper, which offers them knowledgeable religious writing.” Footnote 116 Many “famous ʿulamaʾ . . . prohibited their sons from reading newspapers and journals after sending them to Najaf to be educated,” but they soon began making an exception for al-ʿIlm. Similarly, Arab shaykhs in rural areas used to burn any newspaper that fell into their hands, but they “changed their views” after partaking in al-ʿIlm and became interested in other newspapers as a result.Footnote 117

In recounting how issues of al-ʿIlm and the other periodicals that al-ʿIlm attracted to Najaf were distributed through existing spaces and institutions in the shrine cities, al-Shahrastani describes how a newer public sphere of print media converged with an older one of libraries and majlis gatherings (pl. majālis). The famous majālis of Najaf are recounted in many memoirs and Arabic-language histories of the city as constitutive of a generation of reformers and political dissidents. According to Mufriji, there was hardly a house in the city (presumably above a certain class level) that never hosted such gatherings, and they also were held in gardens, along the lake, and in the desert outside of town.Footnote 118 The majālis, he writes, were places where different classes mixed; there was a majlis for everyone's tastes, desires, and needs, such that Najaf itself could be thought of as a “vast club.”Footnote 119 Some were like “lecture halls”; others functioned as “courts of law”; some were “fatwa-giving majālis”; there were numerous poetry diwans; and many became centers of reformist agitation, helping to produce a “generation that took on the responsibility of reforming everything unacceptable in the society.”Footnote 120

Students and other intellectuals often made a habit of attending several majālis a day. Jaʿfar al-Khalili recounts:

I passed my time at the diwān of [ʿAli] al-Sharqi's house, where I was known to sit with the people in the second-floor room. . . . When his majlis ended, I would go to another diwān, that of Shaykh Jawad al-Jawahiri, and after that one was finished I would head to the diwan of Muhammad ʿAli Bahr al-ʿUlum.Footnote 121

It may not be a coincidence that the three figures recalled by al-Khalili had in the meantime become well-known political figures in the great Iraqi thawra of 1920, but it does mark the way in which these majālis were remembered by those who attended them as schools of insurgency.Footnote 122 Al-ʿIlm has likewise been remembered as helping to inspire the Najafi nahḍa and later anticolonial uprising. Historian ʿUdayy ʿAbd al-Zahra Mufriji writes that the journal helped guide Najaf's reform movement; Najafi poet ʿAli al-Khaqani recounts that it “nourished the souls of the youth”; and historian ʿAbd Allah al-Fayyad asserts that it paved the way for the events of 1920.Footnote 123

In suggesting that al-Shahrastani's journal was part of this world-making project, I am not trying to define a bounded empirical entity, e.g., the al-ʿIlm–reading Shiʿi public. I do not have ways of determining how far each issue traveled through libraries, majlis gatherings, and hand-to-hand sharing, or what its relation was to other circulating journals in this regard. In any case, Warner's publics are not bounded entities, and the Shiʿi public of the shrine cities was not a stable one. During the war, it would arguably mutate into several counterpublics. Mainly what I want to gesture toward here are the resonances between al-Shahrastani's ideas about Islamic sociality and tahdhīb al-nafs on the one hand and the nonstate-aligned social activities and institutions that helped form this soon-to-be insurgent Najafi public on the other.

“Al-Ijtimā ʿ Does Not Remain”

At the end of the journal's first year, al-Shahrastani wrote a remarkably personal reflection on the “benefits and harms” it had brought its founder, himself. He noted several benefits, including the chance to spread his ideas to remote countries and access to periodicals and books sent to him for free.Footnote 124 The list of harms was much longer, fourteen in total. The first was his “fall in the eyes of the public, most of the ascetics, and a group of the men of religion, especially the anti-constitutionalists.”Footnote 125 Others included damage to relationships, including with friends who were unhappy with something he wrote; the demands on his time, which had impeded his juristic duties and his capacity to work on his own ethical and intellectual development (takmīl nafsihi ʿilmān wa-akhlāqān); and the health effects of his physical and mental exhaustion, about which his friends were issuing dire warnings.Footnote 126

Although he continued to publish the journal for another year, at the end of 1911 he shut it down, reportedly due to pressure from senior ʿulamaʾ over his articles criticizing the Shiʿi corpse traffic as unhygienic and un-Islamic.Footnote 127 Shortly afterward, he embarked on his trip across the Persian Gulf to India. According to al-Bahadili, he established a number of Islamic reform associations as he went. The first was in Baghdad, called Jamiʿyyat Khidmat al-Islam (Society for the Service of Islam), and the second in ʿAmara in Iraq, which he named al-Jamiʿyya al-Islamiyya (the Islamic Society). Arriving in Bahrain, he purportedly established al-Islah (Reform); in Oman, al-Ittifaq al-ʿUmani (the Omani Accord); and in Calcutta, Junud Allah (Soldiers of God).Footnote 128 However, according to Ismael Taha Aljaberi, a leading expert on al-Shahrastani's reformist thought and a curator of his archives, he used the trip as an opportunity to imagine and write about the kinds of associations he would like to found, rather than actually founding them.Footnote 129 In any case, the diaries he kept of his trip include several sets of draft bylaws for these associations.

In a two-page introduction to one bylaws draft, al-Shahrastani explained his reasons for founding the association, namely that he had witnessed the emergence of “disease” in the “social body” (al-hayʾa al-ijtimāʿiyya) of the umma. This was due to the disintegration of those bonds that, in the period of early Islam, had been stronger than in any other umma. “The enemies [of the Muslims] describe them today as their enemies were described in the past: ‘They have dismantled their homes with their own hands’ and ‘You may think they are together but their hearts are scattered, because they are a nation that does not understand.’” Many potential “doctors” of this disease in the social fabric “despaired of the life of Islam” because of the weakness they saw in its structure and the “difficult-to-treat diseases that were stuck in its body [juththa].”Footnote 130

Al-Shahrastani framed his society-forming project as the fulfillment of a debt he owed to Islam, and specifically to its shariʿa, a term he invoked not in the modern reified sense of “law” but in an older sense of a path along which one is guided in the project of ethical self-formation. “I grew up as a child in a shariʿa [nashaʾtu walīdān fī sharīʿa] that my right-acting ancestors had served” with all the means at their disposal. This religion afforded its followers “great rights” through its practices of self-cultivation. Given this, “it is not justified for someone like me to not be grateful for his blessings” and “to delay standing up in the service of Islam.” But restoring to Islam its “social life” was beyond the capacity of one person. “It demanded a great power comprising associations of Muslims.” Therefore, “it is right for someone like me to call them to al-ijtimāʿ and cooperation in the service of Islam,” so that they may “restore its moral spirit to its structure and its body [iʿādat rūḥihi al-maʿnawī ila haykalihi wa-juthmānihi].” Again, al-ijtimāʿ is the activity through which the spirit of Islam is breathed into the body (juthmān) of the umma.Footnote 131

This “body” should not be understood as a stable one, not only because it can be afflicted by disease but also because its holding together (ijtimāʿ) is not a state or a condition but rather the repetition of actions or works; it disappears if it is not organized and guided along a path that fosters this repetition.

Al-ijtimāʿ does not remain unless it is organized in itself and follows a path and preserves the rights of the individuals in it; so before anything else, I had to create an organization for the association [i.e., the bylaws] and coordinate its principles in accordance with the necessary goal . . . so that the matter would require nothing more except for action.Footnote 132

Gathering together is fostered by the delineation of a path that organizes its repetition; otherwise, the spirit of Islam will fail to continuously revive the mere body of the umma.

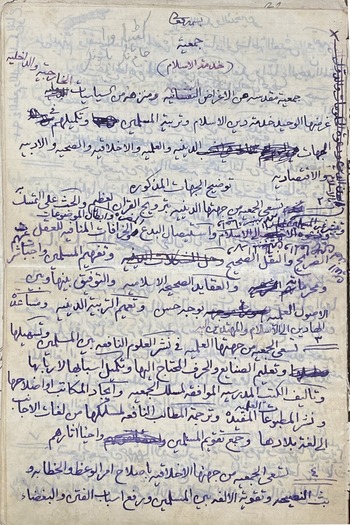

One set of draft bylaws starts with a definition of the society it is constituting as a “sacred association [jamʿiyya muqaddasa] with psychological [nafsāniyya] goals” (Fig. 2). The author then crossed out nafsāniyya and replaced it with the more capacious nafsiyya, which even more than the former word can mean spiritual or mental in addition to psychological. Both words point to the nafs, the self/soul/psyche/spirit that is the object of the work of tahdhīb al-nafs. The societies were oriented toward building what al-Shahrastani, in al-ʿIlm, had described as the “five pillars” of the “character of the modern person” (shakhṣiyyat al-insān al-ʿaṣrī): religion (al-dīn), reason (al-ʿaql), culture (al-adab), freedom (al-ḥurriyya), and morals (al-akhlāq).Footnote 133

Figure 2. First page of draft bylaws for “Jamiʿyyat Khidmat al-Islam,” from Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani, “Qawanin al-Jamiʿyyat al-Islahiyya,” n.d. [1912 or 1913], 4, al-Bandariyyat (manuscript), no. 137, Maktabat al-Jawadain al-ʿAmma, Kadhimiya, Iraq.

The bylaws themselves are arguably unimaginative in comparison to al-Shahrastani's theorizations of ijtimāʿ in other writings and even to the introductions he wrote for them. For example, one provision calls for the “propagation of the religious rulings and the correct beliefs, and the revival of the important practices (sunan),” without gesturing toward what he elsewhere describes as these practices’ capacity to generate social assemblages enabling political mobilization against a threat. They also describe a strikingly ambitious pedagogical project for associations that were not necessarily to be linked to any particular government. They called, inter alia, for the association to print a regular newspaper, found a library, and construct schools to educate boys and girls in modern sciences, Arabic and the local languages of trade, economic skills, hygiene and health, etc., in addition to the principles and required rituals of Islam. They seem to cover nearly all the fields of a contemporary government school, with the possible exception of history, a primary field for the cultivation of nationalism. The societies were to be free of domestic and foreign politics, their only goal being to serve the religion of Islam and cultivate Muslims in the “religious, scientific, moral, health, literary, and economic domains.”Footnote 134 In separating the association from politics, al-Shahrastani marked its dissociation from any particular government. In one bylaws draft, for a society called Jamʿiyyat Islah al-Shiʿa (Shiʿa Reform Association), the author specifies that the group will not do anything that contradicts “the religion or the laws of the local government.”Footnote 135 And another even notes that the society will serve the government to which it is subjected, whether in military institutions, administration, or constitutional councils.Footnote 136 It seems that al-Shahrastani was prepared for some flexibility in each society's relationship to the particular government of the territory in which it was established.

Nevertheless, al-Shahrastani was not, before World War I, intimately involved in a project to adapt Islam to the needs of a modern state. He had no need to devise a system of “all-out legislation in social and political matters” that would be compatible with Islam, as Dyala Hamzah writes of Rida's project.Footnote 137 Neither “public interest” nor “law” as a unitary concept played a significant role in his writings before the war.Footnote 138 He often used the term “al-shariʿa” to refer either to an ethical path of self-cultivation, as described above, or broadly to Islamic truth. In an example of the latter, he insisted on the compatibility between the “Islamic shariʿa and modern science.”Footnote 139 He did write in al-ʿIlm about particular Islamic aḥkām or legal rulings, including on polygamy, divorce, the consumption of alcohol, and the legitimacy of earning interest on loans (which he authorized if the survival of Islam or the independence of Islamic states was at stake).Footnote 140 But these articles are a small proportion of the total content of the journal, and they contain few references to state legislation.

Thawra

If the bylaws were somewhat predictable in their pedagogical content, al-Shahrastani also was beginning to link, in less predictable ways, the religiously grounded practice of nahḍa or revival to a political conception of thawra (revolt or revolution). In 1912, Rida's al-Manar published a one-page essay by al-Shahrastani entitled “Asrar al-Thawra” (Secrets of Revolution), which explored these ideas and arguably prefigured the young cleric's coming participation in political insurgency.Footnote 141 Al-Shahrastani was not alone in invoking thawra as revolution in a positive sense in this period, but neither was he typical. Before World War I, according to Ami Ayalon, the term was used positively to mean “revolution” by only “a handful of mainly Christian intellectuals”; it still mainly had negative connotations—of lawless revolt, bloodshed, and anarchy—including in the writings of Rida, who in 1908 had called it a “distasteful and repugnant thing.”Footnote 142

Al-Shahrastani's essay, written in a language that is poetic and scientific at once, proposes ten secrets, or principles, of al-thawra. I will mention just three of them here.Footnote 143 The second principle is that thawra manifests in different ways on different kinds of material at different speeds: it might start by creeping slowly underground “as a volcano,” or engulf dry straw all at once in flames, or spread as “a fever or rage” in an animal, or as “love or insanity” in a human, or as war or inqilāb (coup/revolution) in a government. Although arriving, in this final image, at the emergent understanding of thawra as a political event, these lines also evoke its earlier meaning of volcanic eruption and assert it as a kind of associative energy that moves through different fields, or bodies, according to different temporalities. We seem to no longer be in the circular imaginary of nahḍa as a repetitive and restorative event, but neither are we in the linear homogeneous time of the nation–state, notwithstanding the allowance for the possibility of inqilāb or state capture.

The third principle flows from the second: “the origin of revolution is the gathering together [ijtimāʿ] of strong influences in the thing,” which exceed its own capacity, and which excite it out of its stillness so that it becomes the carrier of the revolution, in turn influencing others.Footnote 144 This principle resonates with my argument throughout this article that al-Shahrastani's project was not so much about the slow work of remaking subjects through state-aligned and future-oriented disciplinary projects to create self-directed or autonomous citizens. It was about enlivening Muslim agency in the present by generating more, not fewer, social attachments.Footnote 145

In the tenth and final secret, al-Shahrastani shifts to the “literary revolution” or the “ethical revolution” (al-thawra al-adabiyya), which he describes as “a school of knowledge” that “cultivates ideas” and “brings out hidden morals [or character, akhlāq].”Footnote 146 The linguistic ambiguity of adabiyya, as literary and/or ethical, was productive here, conceptually linking the public sphere of the Nahda with the need for ethical pedagogy (the cultivation of the self), and connecting both to thawra, the possibility of political revolution.

I end this article with al-Shahrastani's brief, enigmatic, and open-ended poetic essay on thawra as a gesture toward the coming storm but also to reject analytical closure around his ideas or his political practice. In a similar vein, it may be worth mentioning that the derivative discourse model of Islamic reform has sometimes been accompanied by assertions that Islamic modernism was an elite project that failed to connect to popular politics. For example, Rudolph Peters argues that since the “Islamification” of “Western values” appealed only to the “Europeanized” elites, “pan-Islamism never became a mass movement” and “almost nowhere . . . did Islam play a crucial role as an ideology of anticolonial resistance. The endeavors of Jamal al-Din and Rashid Rida had little effect.”Footnote 147 Regardless of whether this statement holds true for these two reformers, the same can certainly not be said about the endeavors of al-Shahrastani and other Shiʿi constitutionalist clerics in the late Ottoman shrine cities, who from 1918 to 1920 would become leading figures in one of the most significant anticolonial insurgencies to confront the British empire in the 20th century. Although that history lies beyond the scope of this article, I have attempted to show here that the life and work of al-Shahrastani provide generative material for considering the interplay between revivalist concepts and anticolonial thought in the final years of the Nahda and the Ottoman Empire.

Acknowledgments

Gabriel Young was a dream research assistant in the early pandemic era, the summer of 2020, assembling a significant archive of sources online to begin a larger project on the intellectual genealogy of the 1920 revolt, which led me inter alia to al-Shahrastani. In Iraq in the summer of 2022, Ismael Taha Aljaberi (“al-Jabiri” in the transliterated citations above) provided incredibly generous assistance navigating al-Shahrastani's archives and prewar reformist thought. The directors and staff of the Jawadain library in Kadhimiya made this part of the research possible; I especially thank Shaykh ʿImad Alkazemi and Shaykh Munir Alkazemi for helping me access the archives and connecting me to Dr. Aljaberi. In Najaf, Faez Albaidhani provided very helpful research assistance. For close readings of and insightful comments on various drafts of this article, I also am grateful to Spencer Bastedo, Samera Esmeir, Saygun Gökarıksel, Samira Haj, Zachary Lockman, Milad Odabaei, Leila Pourtavaf, Joan Scott, and the participants in the writing workshop of the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in fall 2022. Finally, I thank the three anonymous reviewers and Joel Gordon at IJMES for introducing me to important relevant scholarship and pushing me to develop my arguments more boldly and coherently.