INTRODUCTION

A new way of observing the world emerged in the early Renaissance. It demonstrated itself most beautifully in painting and sculpture, but it shaped the study of the past with no less vibrancy. From Leonardo Bruni (1370–1447) to Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540), archival and literary sources began to be read more critically and formed the basis of complex analyses of past events, peoples, and places. At the same time, less polished, more experimental studies on similar subjects were made using material sources. From the time of Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), ancient objects such as coins, statues, and buildings became evidence in the investigation of historical change. In Poggio's generation, these studies included descriptions (often inelegantly written) of ancient objects, amateur drawings of antiquities, and bare lists of ancient inscriptions. The coarse nature of these studies of material sources is a hint in itself that they were often made from firsthand observation.

The most coherent of these first investigations of material sources dealt with inscriptions. Studies of inscriptions survive in abundance from the early fifteenth century on.Footnote 1 They were initially recorded in manuscripts, and drawn primarily from observations of buildings and monuments, especially those thought to be ancient Roman. Not only did a great number of individuals begin to compile such records—dozens of fifteenth-century sylloges still survive—but the scale of their work was transformative.

Numbers give a sense of just how expansive the endeavor was. Somewhere between 1405 and 1430, Poggio copied a total of eighty-seven ancient inscriptions in Rome.Footnote 2 Just a few decades later, by the end of his life Ciriaco d'Ancona (1391–1452) had copied more than one thousand ancient inscriptions from across Italy and the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 3 In 1488–89, Giovanni Giocondo copied 540 inscriptions in Rome.Footnote 4 In 1521, Giacomo Mazzocchi published Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Inscriptions of the ancient city), a collection of three thousand inscriptions found in Rome.Footnote 5 And, in 1602–03, Jan Gruter, Joseph Scaliger, and Marcus Welser published twelve thousand Greek and Latin inscriptions in Inscriptiones Antiquae Totius Orbis Romani (Ancient inscriptions from the whole of the Roman world).Footnote 6 The scale of epigraphic scholarship continued to increase after them, and today 180,000 ancient Latin inscriptions from across Europe and the Mediterranean are known, to say nothing of those in other languages, from other places, and from other historical periods.Footnote 7

The way in which the learned descended with notebook in hand on the world's cities and open countryside in search of inscriptions, among other types of antiquities, raises the question: How and why did this movement begin? To my knowledge, this question has only been studied in a general way before. That material remains of the past began to be examined more systematically in the fifteenth century has been known since at least Jacob Burckhardt (1818–97), who linked this shift to the interest in classical antiquity cultivated by humanists.Footnote 8 Arnaldo Momigliano probed its origins further and found them in what he called the classical “antiquarian” tradition, which humanists revived after a period of medieval slumber.Footnote 9 He argued that Poggio's generation and their successors imitated ancient antiquarian examples, such as Varro's Human and Divine Antiquities. More recent studies have cast doubt on the movement's classical origins.Footnote 10 Instead, Roberto Weiss's later assessment has remained dominant. Weiss argued that the new critical approach to classical texts first developed by humanists drove them to search out new sources not only in texts and manuscripts but also in material remains.Footnote 11

The study of inscriptions has thus been retrospectively lumped together with various other types of studies of antiquities from this period, such as descriptions, drawings, classifications, and analyses of coins, statues, buildings, and so on. The origins of these different types of studies, whether in a classical antiquarian tradition or in new humanist ideas, have been seen as one and the same. A new erudite mindset—a new value of all things ancient, a new sense of the past, a new ideal of critical scholarship—motivated scholars across Italy to leave the comforts of the library and search out and record all remnants of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. The authoritative work on Renaissance epigraphy by William Stenhouse builds on this presupposition.Footnote 12

However, I have found that the study of inscriptions developed in a special way. It was originally practiced in quotidian contexts in Italy and Greece by members of the social elite who observed inscribed buildings and monuments, collected and displayed inscribed fragments, and conversed about them. These individuals’ expert knowledge of inscriptions became essential to the work of humanists. Once humanists happened upon a ninth-century manuscript collection of inscriptions now known as the Einsiedeln sylloge, in the library of St. Gallen, they used it as their model to produce new records. Touring antiquities with the elite in Italian cities and commercial outposts, they created new manuscript collections of inscriptions. Once these two contexts—the social and the learned—came together, the practice of recording inscriptions exploded and the foundation for epigraphy was laid.

This synthesis first occurred to great consequence in the work of Ciriaco. The scale of his records of inscriptions was ten times greater than that of his predecessors and most of his immediate successors, and his collection's geographical scope was unmatched until the following century. For these reasons, Theodore Mommsen and Giovanni Battista de Rossi named him “the founder of our discipline.”Footnote 13 In this article, I show how and why Ciriaco came to build on medieval traditions and new humanist ideas to produce this revolutionary work. These findings thus shed light on the origins of the discipline of epigraphy and, to some extent, on the surge of general interest in examining the material remains of the past that occurred during this period.

THE TRADITION OF THE URBAN ELITE

Ciriaco has long been recognized for his importance to early Renaissance thought.Footnote 14 He traveled in Italy and the Mediterranean continuously throughout his life, taking note of just about everything he saw and experienced, and his records were significant not only to epigraphy. He composed countless descriptions of ancient buildings and objects, often including their measurements and details of their iconography.Footnote 15 His drawings, which were at least fifty in total, were similarly detailed. His image of the Parthenon still survives in his own hand, most famously, but most others survive through copies or as sources of influence for works like Mantegna's Parnassus and Agony in the Garden.Footnote 16

Inscriptions have thus been seen as one of his many pursuits, and consequently, modern scholars have not analyzed the development of his interest in this subject in particular, nor its origins. Following consensus about early modern antiquarian scholarship, it is generally assumed that the Florentine humanists, led by Poggio, whom Ciriaco met some time after 1424, inspired him to study classical texts and objects. Recently, an alternative interpretation has been proposed by Giorgio Mangani.Footnote 17 Mangani argues that it was Ciriaco's contacts with Eastern Roman scholars, especially Gemistos Plethon and Cardinal Bessarion, whom Ciriaco met in the 1430s, that shaped his studies.

All of these contacts, however, postdate Ciriaco's first examination of antiquities, including inscriptions. His studies began at an early age and took place in cities beyond the sophisticated centers of learning in Florence, Rome, Mistra, and Constantinople. To be sure, the culture of Italy and the broader Mediterranean were crucial to his work, but it was in the intermediary places that his interest in antiquities initially developed, and those places later came to be essential to his work. This development is documented in the biography written by his friend Francesco Scalamonti.Footnote 18 Scalamonti composed the biography on the basis of Ciriaco's first travel diaries,Footnote 19 which have now been lost, in many places copying them verbatim.Footnote 20 Throughout the biography and the surviving diaries and letters there is a clear pattern. During his travels, Ciriaco was welcomed by the local elite in most places he visited and, as a kind of social activity, was given personal tours of notable sites in the area, which included remarkable buildings, ancient monuments, ruins, and inscriptions. His first tours preceded his humanist studies with Florentine and Eastern Roman scholars.

Ciriaco was a highly successful merchant, at first trading in goods such as chestnuts and fir trees, which is why he traveled frequently and came to know the Mediterranean elite.Footnote 21 He was originally of relatively modest social status. According to Scalamonti, he was “a scion of the noble patrician family of the Pizzecolli,” and his father, also a merchant, had lost his wealth to shipwrecks and pirate raids when Ciriaco was a boy.Footnote 22 But Ciriaco's patrician relations as well as his exceptional business acumen helped to elevate him to some of the highest echelons of society. In his youth, he rose quickly through the ranks of the company owned by his extended Anconitan family, which brought him into business with eminent Venetian families, including the Quirini and Contarini.Footnote 23 He also held several public offices. For instance, before finishing his apprenticeship, he was elevated to the consular rank as one of the six anziani of Ancona, and later served in the senate.Footnote 24 Serving in such positions over the course of his life helped him to become a rather prominent member of the urban elite himself.

The first time Ciriaco is known to have toured antiquities with members of the local elite was during his visit to Palermo in 1415, when he was in his early twenties and working for his family's company.Footnote 25 After unloading his goods, he stayed for several days with a certain knight and count, “in whose humane company,” Ciriaco reports, “we inspected the fine porticoes known as the Tocci, the richly decorated churches, the splendid palace of the Grand Admiral Chiaramonte, and the remarkable Royal Chapel of St. Peter in the palace with its porphyry marble and marvelously worked mosaics.”Footnote 26 In this interaction, the old Sicilian nobility showed Ciriaco old and new buildings alike, and did not emphasize their antiquity, specially, but rather their craftsmanship.

This pattern of social exchange, in which the old-landed nobility and merchants walked together and viewed local buildings, was common in late medieval Italy. There were similar instances in Ciriaco's boyhood, when his grandfather took him to see the sights in Italy, such as the city walls and the castles, with their painted halls and caged lions, in Venice, Padua, and Naples in 1401–03—under the guidance of the nobility, with whom his grandfather was clearly close.Footnote 27 During the same trip across Italy, the two of them stayed as guests of the Duke of Sessa, and Ciriaco remembers that he became fast friends with the duke's son, “despite their difference in education and upbringing.”Footnote 28 The difference between the nobility and patriciate was overcome with the help of certain shared social practices, of which guided city tours were a prime example. Such interactions introduced Ciriaco to high society, which is why he was careful to record them in his diaries, in typical merchant fashion, but they also taught him about the local forms of architecture and notable sites.Footnote 29 In communities where ancient monuments in particular were valued, he learned to take an interest in the distant past.

The next tour Ciriaco was given by the local elite was in Constantinople in 1418.Footnote 30 There he was received by the consul of Ancona in the city, who showed him many of the city's sights. He saw dozens of monuments, such as the city walls, the royal Golden Gate, the Hagia Sophia, the “equestrian statue of Heraclius,” and the Hippodrome.Footnote 31 Ciriaco took special note of the Hippodrome and its inscriptions. “And most of all,” Scalamonti writes, “he admired the enormous obelisk made from a single block of Numidian stone, and inscribed on all sides with hieroglyphs which, as they learned from the Greek and Latin inscriptions below, was erected to the order of the emperor Theodosius by the architect Proculus.”Footnote 32 At this point, Ciriaco had not studied ancient Greek or Latin, which he began after coming into contact with humanists in Italy, in 1421. He must have relied on his more learned companions to read the inscriptions for him.

Ciriaco's next guided tour similarly turned his attention to the ancient monuments and, specifically, to their inscriptions. Visiting Pola in 1419, he saw a great number of ruins both inside and outside the city walls, including “numerous stone tombs, many of whose epitaphs he transcribed, being accompanied and much helped by Andrea Contarini, who was then the Venetian governor of the city.”Footnote 33 As in Constantinople, interest in material antiquities had become a ritual of elite culture.

These are the three key moments in Ciriaco's study of antiquities—in Palermo, Constantinople, and Pola between 1415 and 1419—that are recorded in the biography and precede his turn toward the systematic study of ancient texts. Together they suggest, first of all, that Ciriaco originally acquired his interest in antiquity from members of the Italian elite, and, second, that already in the early fifteenth century, the elite valued ancient monuments not simply because they were made of precious material, as was often the case in the early Middle Ages, but also because they held a certain meaning.

Even after Ciriaco began to study ancient texts—in his case, especially Homer, Ovid, Pliny, and Strabo—he continued to rely largely on his local guides, rather than on the facts and ideas he found in texts, to locate and understand monuments of the past. In his writing, he was always careful to name his guides.

The individuals Ciriaco met are tabulated in part in the appendix to this article, using his own language to identify them.Footnote 34 The information included in brackets is supplemented from external sources.Footnote 35 Unknown information is denoted with an x. This table includes only the instances in which Ciriaco explicitly identified the individuals who led him to the notable sites. In total he may have made as many as several hundred tours, many of which were documented in the biography and his diaries and letters. Ciriaco was almost always accompanied by locals on these tours, as he indicates in his writings, but only in the instances tabulated did he explicitly indicate their expertise. For instance, in 1444, he said of the entourage led by Palamede Gattilusio (ca. 1389–1455) in Ainos that “they expertly showed me all of the city's important sites.”Footnote 36 These individuals were not only familiar with the area, as one might expect of any local, but they also had specific knowledge of the notable monuments.

Ciriaco's diverse experiences, scattered in time and space, had common elements. The first is that the individuals whom he met were largely Italian in origin. The majority of the settings for their tours, some 64 percent, were Italian territories. Most were colonies or commercial outposts governed by Italian cities, especially Venice and Genoa. Several outposts were held by other cities, including Ancona and Florence. In many of these cases, the territories had been held by Italian cities for so long that the individuals whom Ciriaco met, such as Palamede, had actually been born there. Their families originated in Italy, however, and many retained their allegiance to those native cities. The rest of the territories Ciriaco visited with expert guides were Eastern Roman, some 21 percent, and Ottoman, about 14 percent. Clearly, Italian colonization of the eastern Mediterranean, which became substantial after the Fourth Crusade, was instrumental in the systematic examination of the new territories and their artifacts.

Another common element is that most of Ciriaco's guides—about 79 percent—either owned the land in or around the city or governed the city itself. They held noble titles, such as knight and count; they were ecclesiastic dignitaries, such as bishops and abbots; or they worked in governance, holding positions such as consul or praetor. The rest were unidentified “local inhabitants” (probably laborers), as well as lesser ecclesiastics, merchants primarily engaged in commerce (rather than politics), scholars, craftsmen, and sailors. In short, the people who were both the most knowledgeable about the places Ciriaco toured and the most interested in showing him around were those who owned or governed the cities and their surrounding lands.

The social status of Ciriaco's interlocutors is also revealing. Those who came from old noble families made up roughly 33 percent of the elite individuals Ciriaco encountered. By contrast, about 61 percent were from families that owned less land, earning their wealth primarily from commerce and other endeavors. The rest were secretaries serving the government. Of all these urban families, 41 percent were prominent enough to appear in the Treccani encyclopedia. The remaining 59 percent were either minor patricians, such as Ciriaco's family (which is not in Treccani), or not part of the aristocracy at all. Although some of his informants were of high birth, most were from newer, less eminent families.

Equally revealing are the types of sights these individuals chose to show Ciriaco. The table includes only the first objects he saw (again, using his own language to describe them), since he does not make clear when he parted ways with the guides.Footnote 37 Of these, some 74 percent were described as “ancient” or “old” monuments. Of these antiquities, 17 percent were inscribed. Most of the monuments were classical Greek and Roman objects, though it is important to note that this category was not fully developed at the time and can only be applied retrospectively. Some 12 percent were “new” monuments, which included civic and commercial buildings and objects. Ten percent were Christian monuments, also not yet a defined category. The rest were a miscellany of sights of foreign customs and natural phenomena. The preponderance of ancient objects is clear.

In sum, Ciriaco acquired a general interest in antiquities, as well as a general skill in their observation, through the local expertise of the Italian urban elite living in Italy and the eastern Mediterranean.

Now, how did the urban elite know where to find antiquities? Many of them were mysterious structures lying in ruins in the fields; others were limbless statues or broken columns. Yet they seem to have searched for them with just as much curiosity as Ciriaco expressed in his writings.

Ownership has a way of making the heart grow fonder. In Italy, the practice of searching out and acquiring antiquities had a long history by the fifteenth century.Footnote 38 The urban elite living on the peninsula had considered antiquities meaningful objects since their formation as a political and social body, in the twelfth century.Footnote 39 With the erosion of papal and imperial authority in Italy, ambitious families vied for independence. They took over the governance of cities and defended their precariously won positions, in part by arguing that their long and illustrious histories legitimized their rule, as Carrie Beneš has shown.Footnote 40 They made this argument explicitly by composing chronicles and histories demonstrating—in some cases inventing—the ancient origins of their families and the cities they governed.Footnote 41 And they made it implicitly by decorating their private tombs, their homes, and their civic buildings and squares with ancient objects.Footnote 42

The rise of the urban elite, which incorporated both old-landed nobility and new families that made their wealth from commerce and banking, led to a rise in the political and social reuse of antiquities. Before, only the old-landed nobility had done so. Ancient sarcophagi were the most widely reused object, for example.Footnote 43 Beatrice of Lorraine, Marchioness of Tuscany, was buried in an ancient sarcophagus illustrated with the story of Hippolytus and Phaedra in Pisa in the late eleventh century.Footnote 44 Meanwhile, popes took the tombs of ancient emperors. The ascent of commercial families gave them the means to do the same. The Agnelli family of Pisa, for instance, rose to prominence in the fourteenth century through business ventures, such as wool production, landholding, and serving in government positions.Footnote 45 One member of the family was buried in an ancient Roman tomb.Footnote 46 Several similar examples are known as well. As the number of families engaging in the practice increased, so, too, did the rediscovery of antiquities.

Larger-scale uses of antiquities for political purposes are known across cities in Italy from the late Middle Ages. Churches were ornamented with Roman-sculpted funerary reliefs. Palaces were installed with prominent pediments from Roman temples.Footnote 47 Markets were clustered around Roman monuments. Cities built on ancient foundations often had material remains nearby, which were easily brought into the center. Those that lacked antiquities had them brought in from places like Rome and Ostia, which had a seemingly endless supply, or they had artisans craft new objects that appeared ancient in script or iconography.Footnote 48 Modern scholars have identified medieval cases of purposefully reused antiquities in Salerno, Amalfi, Rome, Perugia, Pisa, Genoa, Siena, Modena, Verona, Padua, and Venice.Footnote 49 Probably more are known.

Inscribed ancient stones, in particular, were used in special ways in some of these cities. Most, if not all, of the urban elite could read parts of them. Many knew Latin, but vernacular literacy alone was enough to make out some of the inscribed names and titles. The rise of commercial education further increased the already high literacy rates of Italian cities. As families searched for antiquities with which to ennoble themselves and their cities, they readily picked up on famous names that appeared in inscriptions. This was the case, for example, in Padua in 1305–09, when a farmer discovered an ancient inscription in a nearby field.Footnote 50 It bore the name Livius, and it was assumed to be the epitaph of Titus Livy, so it was proudly immured in the wall of Santa Giustina. Later, Petrarch sat before it while reverently composing a letter to him. A similar example can be found in eleventh-century Pisa, where the duomo was copiously ornamented with Roman inscriptions.Footnote 51

Ancient inscriptions were also used to prove the ancient ancestry of individual families. In Rome, new families perused the names found on ancient stones and adopted them as their own in order to invent ancient genealogies for themselves, as Kathleen Wren Christian has revealed.Footnote 52 Perhaps as early as the eleventh century, the Anguillara “de Monumento” took their family name from an ancient tomb on the Via Tiburtina.Footnote 53 Other families looked for names that more or less resembled their own given names. For example, in the early fifteenth century, the Porcari family collected and displayed inscriptions bearing the name Marcus Porcius Cato, whom they fashioned as their fictive forefather.Footnote 54

Clearly, this tradition continued into Ciriaco's lifetime. Both antiquities generally and inscriptions in particular were displayed in cities across Northern Italy during his time.Footnote 55 Ciriaco observed several cases. In 1433–34, he noted instances of reuse in his observations of ancient material in Modena, Milan, Brescia, Verona, and Mantua.Footnote 56 For example, he saw an inscribed ancient Roman tombstone “set up in the marketplace” in Modena.Footnote 57 In Milan, moreover, he saw an ancient Roman inscription displayed “on the wall of the house of Enrico Panigarola,” a merchant who later ruled in the short-lived Ambrosian Republic against the Visconti.Footnote 58 These cases, and the history of the movement generally, suggest that the urban elite who took Ciriaco on tours in Italy were knowledgeable about the area because they had searched for antiquities for their own uses. So much for the case of the Italian peninsula.

In the eastern Mediterranean colonies and commercial outposts governed by Italian cities, the situation seems to have been similar. With the successes of the Crusades for Westerners, Italian cities were granted trading rights in the Eastern Roman Empire and conquered parts of their territories. Many Italians came and went. Others settled long term. For both those who returned to Italy and those who stayed, the newly won lands created opportunities for ambitious individuals of nonaristocratic origins to acquire wealth and status.Footnote 59 They ransacked cities for gold and precious goods and cornered commercial markets. Many took over governance of cities and islands. In some of these places, local governors bolstered their newly established authority by displaying antiquities in civic spaces.

Travelers took some antiquities home, as Patricia Fortini Brown has shown. The ancient bronze horses taken from Constantinople in ca. 1250 to adorn the Basilica of San Marco, in Venice, where they still stand today, are the most famous of these antiquities.Footnote 60 More minor cases are also known. For example, the galley captain Domenico Morosini, who transported the horses, took one of their hooves for himself.Footnote 61 This piece was passed down in his family for generations, until it was prominently installed on the facade of the house of one of his descendants in Venice.Footnote 62 These and other examples like them reveal that, to some extent, traveling Crusaders searched the lands formerly held by the Eastern Roman Empire for antiquities with which to adorn their native cities and homes.

Meanwhile, settlers built fortifications, churches, palaces, and houses on the Greek islands and mainland. They incorporated antiquities in these constructions. Some cases have been found by modern scholars in late medieval Crete, Panakton, Paros, and Cyprus.Footnote 63 Probably other cases are known, but the custom was, perhaps, still relatively rare compared to what was practiced on the Italian peninsula in the same period.

But by Ciriaco's time, this had changed. In 1417, not long before Ciriaco, his fellow learned traveler Cristoforo Buondelmonti (ca. 1385–ca. 1430) reported that he saw a statue garden made by Venetian nobleman Niccolò Scipio in Crete, which included busts of Marc Antony and Pompey, as well as “beautiful marble that had been brought there from other structures.”Footnote 64 He also described an instance in 1420 in which he and a few others attempted to raise a statue on columns with ropes in Delos.Footnote 65

Not long after, between 1430 and 1444, Ciriaco noticed relocated antiquities in cities throughout the eastern Mediterranean, including in Thessaloniki, Aphamnia, Perinthus, Imbros, Samothrace, Thasos, Naxos, Mykonos, Paros, Mytilene, Tainaron, Porto Quaglio, Merbaka, and Locris.Footnote 66 He also purchased gold coins of Philip, Alexander, and Lysimachus in Foglia Nuova in 1431.Footnote 67 Ciriaco's earliest recorded observation of the purposeful display of a relocated antiquity was in Thessaloniki in 1430, where he saw an ancient inscription that had been “brought from Mount Helicon,” probably by the Venetians, who had governed the city since 1423, or the Eastern Romans before them.Footnote 68 Another notable example is the ancient inscription that he saw in 1444 immured in the house of the Venetian Duke of Naxos, which he described as “brought from elsewhere to adorn the building.”Footnote 69 Most of the places in which Buondelmonti and Ciriaco saw the public display of antiquities were then under Venetian or Genoese rule.

These examples suggest that even before Ciriaco (and Buondelmonti before him) visited the eastern Mediterranean, the urban elite had been searching for antiquities and using them for political and social purposes. They likely followed the tradition established on the Italian peninsula. Some of the urban elite Ciriaco met had been born in Greece, but it was common for them to study in Genoa, Pavia, Padua, and Bologna.Footnote 70 Other local traditions, including those of the Eastern Romans and other Western Crusader settlers, likely reinforced the practice.Footnote 71 But Italian social networks played an instrumental role in creating common customs. They explain how the ubiquitous interest in reusing antiquities in cities developed on the Italian peninsula, as Beneš has argued.Footnote 72 Those same networks and rituals seem to have reached across the sea as well.

In sum, Ciriaco developed an initial curiosity about antiquities and a skill in observing them through conversations with the members of established families whom he met during his travels. His lifelong participation in communal tours may explain why he privileged empirical observation over systematic humanist study of antiquities, as Chatzidakis has demonstrated. As the scale of social mobility increased with the rise of the communes and the successes of the Crusades, which created wealth and opportunity in governance for a larger number of families, the practice of reusing antiquities, as the old-landed nobility had done, became widespread. The growing vibrancy of this medieval tradition resulted in an increase in the examination of local antiquities in both Italy and the newly conquered eastern Mediterranean territories.

These social conditions gave rise to a new culture of observation. The tour of the grounds emerged as a common activity, leading a growing number of people to explore local architecture, art, and antiquities. As Ciriaco's writings testify, the more they looked at objects together, the more they began to see and articulate distinctions and patterns in various materials, ages of stones, levels of craftsmanship, and images and texts, all of which they expressed primarily in conversation.

THE CHRISTIAN TRADITION

Gradually, conversations about antiquities turned to written accounts. Ciriaco had begun to keep records of his observations of antiquities early on, but they became focused and systematic only after he came into contact with humanists in Rome and Florence. The differences between his early and later records reveal that he learned of the Einsiedeln sylloge from them. They subsequently became the model for his work.

At first, Ciriaco must have kept vernacular records of his experiences and observations, which have now been lost. They likely formed the basis for his later diaries, which he composed in Latin and referred to as his “commentaries,” and which, in turn, were the basis of Scalamonti's biography. Otherwise, it seems unlikely that such a great level of detail about his first experiences— which include dozens of places he visited, people he met, and sights he saw, in chronological order—could have been preserved or entirely fabricated. The practice of keeping vernacular diaries was widespread among merchants during this period—take, for example, the ricordanze in Florence.Footnote 73 Documenting his elite contacts, the prestigious government positions he held, and his elevated interests, Ciriaco used the diary as a demonstration of status.

After visiting Rome for the first time, in 1424, Ciriaco began to compose diaries in Latin. By then he had met, crucially, Cardinal Gabriele Condulmer, who would later be elected Pope Eugenius IV. It seems to have been under his influence that Ciriaco was inspired to begin studying Latin and ancient Greek, as Condulmer had been doing at the time.Footnote 74 Ciriaco came to Rome in the first place to visit Condulmer, and through him, he met his family as well as the Colonna and other members of the urban elite.Footnote 75 Together with this elect group, Ciriaco observed and conversed about the local monuments, much as he had done in the greater Mediterranean. But now, the conversation was more complex.

Ciriaco writes that, on a walk with the Colonna family, they read the inscription on the Arch of Severus Septimus and discussed how it demonstrated the great heights the Roman Empire had reached.Footnote 76 They saw in it stark contrast to the current decline, but felt hope that Rome's current leaders might revive the city and its past glory. In the same year, Poggio had conceived of writing De Varietate Fortunae (On the vicissitudes of fortune, completed 1447–48), in which he described similar conversations between Antonio Loschi and himself, inspired by the ancient monuments they observed together.Footnote 77

In the same year, influenced by Poggio, perhaps, Ciriaco began to record all the noteworthy antiquities he encountered. He announced his purpose thus, according to Scalamonti: “He resolved to see and record antiquities scattered about the world, so that he should not feel that the memorable monuments, which time and the carelessness of men had caused to fall into ruin, should entirely be lost to posterity.”Footnote 78 Accordingly, his first Latin diaries were sweeping in approach. They were a composite of observations, organized like the vernacular merchant's diary in that they were written in the first person and followed a chronological order. But, unlike the merchant's diary, with its local, social scope, his diaries had a much more general intention, which indicates that Caesar's Commentaries were a source of inspiration, as Chatzidakis has argued.Footnote 79 Inscriptions were not yet of special importance to Ciriaco.

His approach changed, however, following his first visit to Florence, in 1433. Between 1424 and 1433 Ciriaco had begun transcribing inscriptions, but only sporadically and only in small numbers. In his diaries, he recorded one in Rome in 1424, one in Philippi in 1430, one in Cyzicus in 1431, one in Mytilene in 1431, and two in Tivoli in 1432.Footnote 80 However, after his visit to Florence, the scale of his activity increased sharply. During a single trip across the Italian peninsula, he recorded six in Modena, in 1433, and, in 1433–34, he recorded thirty-four in Milan, fourteen in Brescia, twenty-three in Verona, four in Mantua, one in Naples, and two in Benevento.Footnote 81

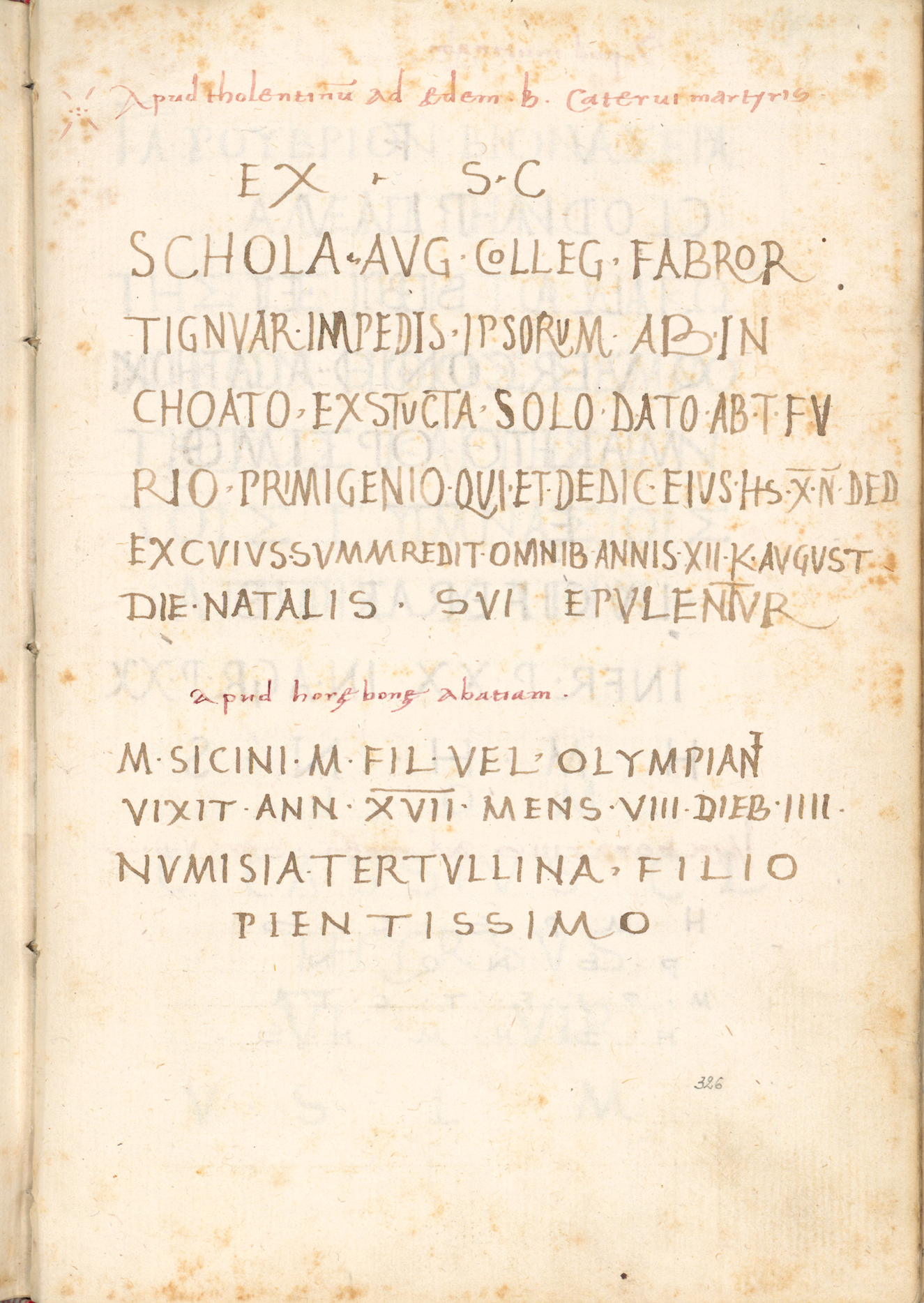

The reason for this change probably lay in Ciriaco's study of the Einsiedeln sylloge, although he never cites it explicitly. Poggio had discovered the manuscript—along with a copy of the first-century glossary of ancient inscription abbreviations made by Marcus Valerius Probus—in St. Gallen in 1417 and brought it back to Italy.Footnote 82 The Einsidlensis is a large-scale collection of inscriptions, both classical and Christian, recorded in the form of a simple list. Poggio made copies of the Einsidlensis, especially its ancient content, which he kept with him in Rome after 1423, and left the original in a Camaldulensian monastery in Florence in 1432.Footnote 83 It is likely that Ciriaco saw this very manuscript in Florence, if not earlier in Rome. But whatever the precise course of events, Ciriaco's records follow the sylloge's form closely. His first collections, which were published in Scalamonti's biography, already begin to reveal this. It should be noted that the biography's scribe was Felice Feliciano (1433–79), who clearly embellished the appearance of Ciriaco's records, though the fundamental structure of the work is likely the same as that of the original.Footnote 84 The records he made from observations in Milan in 1433–34 are preserved (figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Ciriaco's records made in Milan in 1433–34, preserved in Scalamonti's biography (Feliciano's hand). Biblioteca Capitolare del Duomo di Treviso, MS 2 A/I, olim I 138, fol. 73r.

Figure 2. Ciriaco's records made in Milan in 1433–34, preserved in Scalamonti's biography (Feliciano's hand). Biblioteca Capitolare del Duomo di Treviso, MS 2 A/I, olim I 138, fol. 73v.

The essential elements are clear. First, Ciriaco made brief headings indicating the monument or building on which each inscription was located. In this case, the headings are, “At the shrine of St. Nazarius” and “On the front facade of the palace of the praetor.” Next, he transcribed the inscription below each heading. The inscriptions are ancient rather than Christian, something that holds true for the majority of his records. Ciriaco's transcriptions preserve all capital letters and abbreviations found in the inscriptions. The organizing principle of the collection is the topography of the city. The final element to note is that Ciriaco did not provide any kind of analytical apparatus, such as visual illustrations, explications of the inscriptions’ historical context, or an indexing system.

The form is the same in Ciriaco's sylloges, including a version made in his own hand that he gave to Francesco Filelfo (1398–1481) between 1437 and 1440 (fig. 3).Footnote 85 A collection he made with Pietro Donato, probably in 1442–43, also survives, and has the same form.Footnote 86 The similarity between these autographed manuscripts and the biography scripted by Feliciano demonstrates that the biography followed Ciriaco's original records closely.

Figure 3. Ciriaco's records made in Tolentino in ca. 1437–40, preserved in the sylloge he gave to Filelfo (Ciriaco's hand). Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 80.22, fol. 326r. Printed with permission from the Ministero della Cultura. Further reproduction by any means is prohibited.

All of the essential elements of Ciriaco's approach to recording inscriptions—with one exception, which will be discussed below—are also present in the Einsiedeln sylloge (fig. 4). In the Einsiedeln sylloge, even the use of red and black ink to differentiate headings from inscriptions is similar to Ciriaco's collections. As in Ciriaco's works, the headings provide brief indications of the provenance of the inscriptions—for example, “On the tomb of St. Felix,” “In the basilica of St. Bastian,” and “On the Porta Appia.” The content of the inscriptions in this excerpt is both ancient and Christian, which is representative of the collection as a whole. The only significant difference between Ciriaco's collection and the medieval sylloge is the approach to capital letters. In the medieval sylloge, headings are written in capital letters, while the inscriptions are transcribed into minuscule letters.

Figure 4. Einsiedeln Sylloge, ca. ninth century. Einsiedler Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 326 (1076), fol. 78v (www.e-codices.ch).

These similarities reveal that Ciriaco saw either this precise manuscript or one like it, which derived from the same tradition. The Einsidlensis was composed sometime between the mid-eighth and early ninth centuries, probably in Fulda.Footnote 87 It includes a total of eighty-five Greek and Latin inscriptions, seventy-three of which were from Rome and twelve of which were from Pavia.Footnote 88 Slightly more than half are ancient, and the rest are Christian. The ancient Roman content especially piqued the interest of early humanists. But the more significant aspect of the work that they learned was the method of describing antiquity.

The general importance of this Christian method to early humanists has not been discussed by modern scholars, though they frequently cite the fact that Poggio copied parts of the Einsidlensis, and that Ciriaco, in turn, copied parts of Poggio's sylloge.Footnote 89 The Einsidlensis derived from a particular medieval tradition, as De Rossi showed long ago.Footnote 90 About a dozen medieval sylloges like it have now been found. All are substantial lists made originally from observation, ranging from ten to 183 inscriptions in total, and averaging eighty-one.Footnote 91

The medieval tradition of recording inscriptions developed out of an early Christian devotional practice, which is why it was systematic and empirical in nature. The original sylloges were composed between the sixth and ninth centuries by learned pilgrims visiting sacred sites in Rome.Footnote 92 The material inscriptions were important to pilgrims. They knew at which site to pause and worship from the inscriptions marking each site, which had been made on giant plaques since Pope Damasus's reign (366–84).Footnote 93 The late antique poet Prudentius describes their devotional role: “Come, let us with pious tears wash the letters cut on the marble slabs.”Footnote 94 As pilgrims traveled to these shrines, some recorded the inscribed texts in the order in which they saw them as they made their way along the pilgrim routes around the city walls.Footnote 95 Later pilgrims could use the manuscript collections that earlier pilgrims had created as guidebooks for their own travels.Footnote 96 For this reason, the collections were often small in size. The Einsidlensis, for example, was only 18 cm x 12.5 cm, making it easy to carry and consult.

After the ninth century, when popes moved the remaining relics into churches inside the city walls, the practice of walking and recording inscriptions from observation seems to have died down. But the sylloges were nonetheless copied and recopied in the following centuries. Part of the reason for this lasting interest was that the inscriptions Damasus commissioned were composed in the form of metrical verses, vividly describing the life and death of the martyrs. This made the sylloges valuable also to those interested in poetry and the history of martyrs, which is partly why they were preserved.

This treatment of inscriptions was distinctly medieval. It was not like the classical tradition, in which scholars either cited inscriptions as evidence in histories or recorded them among various poems in anthologies.Footnote 97 Classical writers such as Herodotus, Thucydides, Varro, Livy, and Tacitus occasionally recorded laws and treatises, many of which they found inscribed on monuments. And, similarly, those studying poetry, such as Meleagar of Gadara, recorded epigrams, some of which they saw preserved in epitaphs and other material inscriptions.Footnote 98 But many of these epigrams were never inscribed at all, and the collections of them were, accordingly, organized alphabetically or thematically, rather than topographically, since the fact of inscription was not of central importance.Footnote 99 The only notable exceptions from classical antiquity are Craterus of Macedonia and Polemon, who seem to have collected a significant number of inscriptions, perhaps hundreds or even thousands.Footnote 100 But only about twenty of the inscriptions they copied survive. Evidently, their immediate successors did not make copies of their collections or integrate them into new works in any substantial way, which reveals that the interest in inscriptions was limited at the time. In short, classical scholars did not take a systematic interest in copying and identifying inscriptions from observation on a large scale.

It was also a distinctly Western tradition, surprisingly. At other Christian pilgrimage destinations, such as Jerusalem and Constantinople, where there were Eastern Roman inscriptions denoting sacred sites and saints, pilgrims apparently did not copy and compile them. Or, perhaps, not enough study on the subject has yet been done.Footnote 101 There was, however, a scholarly tradition in the Eastern Roman Empire of studying classical and Christian epigrams in the collection now known as the Greek Anthology, which was composed by Cephalas in the ninth century and revised by Planudes in the twelfth or thirteenth century.Footnote 102 This anthology included many classical and Christian inscriptions that were copied from monuments, and their material provenance was noted much as in the Western sylloges, but they were interspersed among far more epigrams that were not inscribed at all, and the work did not, therefore, spark substantial interest in inscriptions per se.

Medieval Christians in the West, on the other hand, treated inscriptions as a subject in their own right. With the sylloges, they read and reflected on them all at once, whether to inform their visit to Rome or to imagine the city from a distance (which is how pilgrim accounts and other guidebooks at the time were used by those who did not travel), or to study and delight in the poetic stories of Roman martyrs.Footnote 103 This is partly why the scale of collection was so large. Much like the medieval lists studied by Umberto Eco, such as the litanies of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the mirabilia accounts, the sylloges created a “dizzying” effect through sheer abundance.Footnote 104 Toward the late Middle Ages, the tendency to accumulate information further expanded, as Ann Blair has shown.Footnote 105 The material context of the texts on the monuments as well as their locations in the city of Rome, which were always preserved in the sylloges, were key to organizing these large collections.

Ciriaco and his contemporaries inherited this medieval Christian tradition. All the other fifteenth-century sylloges that I have seen follow the medieval sylloge's form: they are simple, large-scale lists indicating the provenance of each inscription. In fact, most of them, unlike Ciriaco's, also maintained the medieval focus on Rome. Furthermore, the authors of the fifteenth-century sylloges, as well as their readers, seem to have taken a similar pleasure in reflecting on the content of the inscriptions much as their medieval predecessors had. Ciriaco gives insight into the experience, almost reverent in nature, when he describes how he and his companions discovered an inscription on an ancient arch in Zadar in 1436. “It was not enough to see it only once,” he writes, “but we took pleasure in reading it over and over again.”Footnote 106 Its subject was one Melia Anniana, who sponsored the building of the arch, the statues, and the road below in honor of her husband. Now it was not martyrs who moved travelers, but ancient heroes.

The Christian tradition was reappropriated to fit the needs and interests of a new society. It was revived in Rome in the early fifteenth century, for political and social (and moral) reasons It was only one of many older traditions, both ancient and medieval, that were rekindled in an effort to centralize and grow the authority of the papacy.Footnote 107 During the Western Schism, the city had fallen into disrepair, leaving large areas uninhabited and the rest vulnerable to the violence of competing factions, while many of the ancient monuments had been gutted for building material and the streets and churches left to decay. Following the papacy's return, in 1420, the popes began to restore Rome and, with it, their own power.Footnote 108 As part of the same movement, they commissioned humanists to compose works about the city's distinguished classical origins. The sylloge served this purpose, in part.

For scholarship, the importance of the Christian tradition was great. With the sylloge as their tool, Renaissance scholars began to make regular, precise, and substantial descriptions of antiquities—a departure from their other approaches, which were erratic and often unclear in this early period. The descriptions they composed—such as those by Ciriaco, Poggio, Biondo Flavio, and Leon Battista Alberti, for example—varied widely. Sometimes they included facts about their measurements, structure, material, iconography, and so on, and sometimes they did not. Their drawings were even more unwieldly than their textual descriptions. Some, such as Ciriaco, made detailed and accurate sketches, including jagged lines to indicate fissures in the stone, for instance. Others drew idealized antiquities that came more from imagination than observation, as did Ciriaco's near contemporary Giovanni Marcanova. However, the medieval sylloge gave them focus and method, making their records strikingly consistent.

THE INNOVATIONS OF HUMANISTS

While the form of the medieval sylloge, and the reverent feeling around it, persisted into the fifteenth century and beyond, much also changed. The subject had clearly been turned on its head. It was not Christian Rome but classical antiquity that became the focus of early modern inscription hunters. Since Petrarch, humanists had been developing a systematic interest in the classical past by studying ancient languages and texts and searching for new sources with which to broaden and refine their understanding. Ancient inscriptions became one of the sources serving this purpose, starting at least with Salutati.

In crafting his own records, Ciriaco built on the first two or so decades of humanist study of inscriptions. From the beginning, classical antiquity had been his central concern. His early travels and his informants had already inclined him in this direction and his induction into humanist circles—which were, of course, informed by the interests of the urban elite whom they served—helped him to develop this interest substantially. He learned not only to read Latin and Greek but also to write in both languages. During his travels he bought precious rare books, such as Euripides, Pythagoras, Plutarch's Moralia, and Ptolemy's Geography. Footnote 109 Like his learned contemporaries, he frequently cited such texts in his writings, either to make a point more elegant or to prove a fact. For him, ancient inscriptions were another source deriving from this period of history that had come to fascinate humanists.

Ciriaco was precise in a number of ways that departed from the Christian model. He always preserved capital letters. And, beginning early on, if not from the very outset of his work in this vein, he attempted to reproduce the particular script of each inscription. Some of the earliest recorded inscriptions that survive in his hand are found in the margins of his copy of Ovid's Fasti. Next to the passage describing the Battle of Philippi, he copied six inscriptions he saw in Philippi in 1430.Footnote 110 Here, Ciriaco preserved the sylloge's list-like form as well as the inscriptions’ capital letters. Where medieval Christian pilgrims had been more concerned with the content of the inscriptions, rather than their appearance on the stone, Ciriaco made his records match his observations more closely.

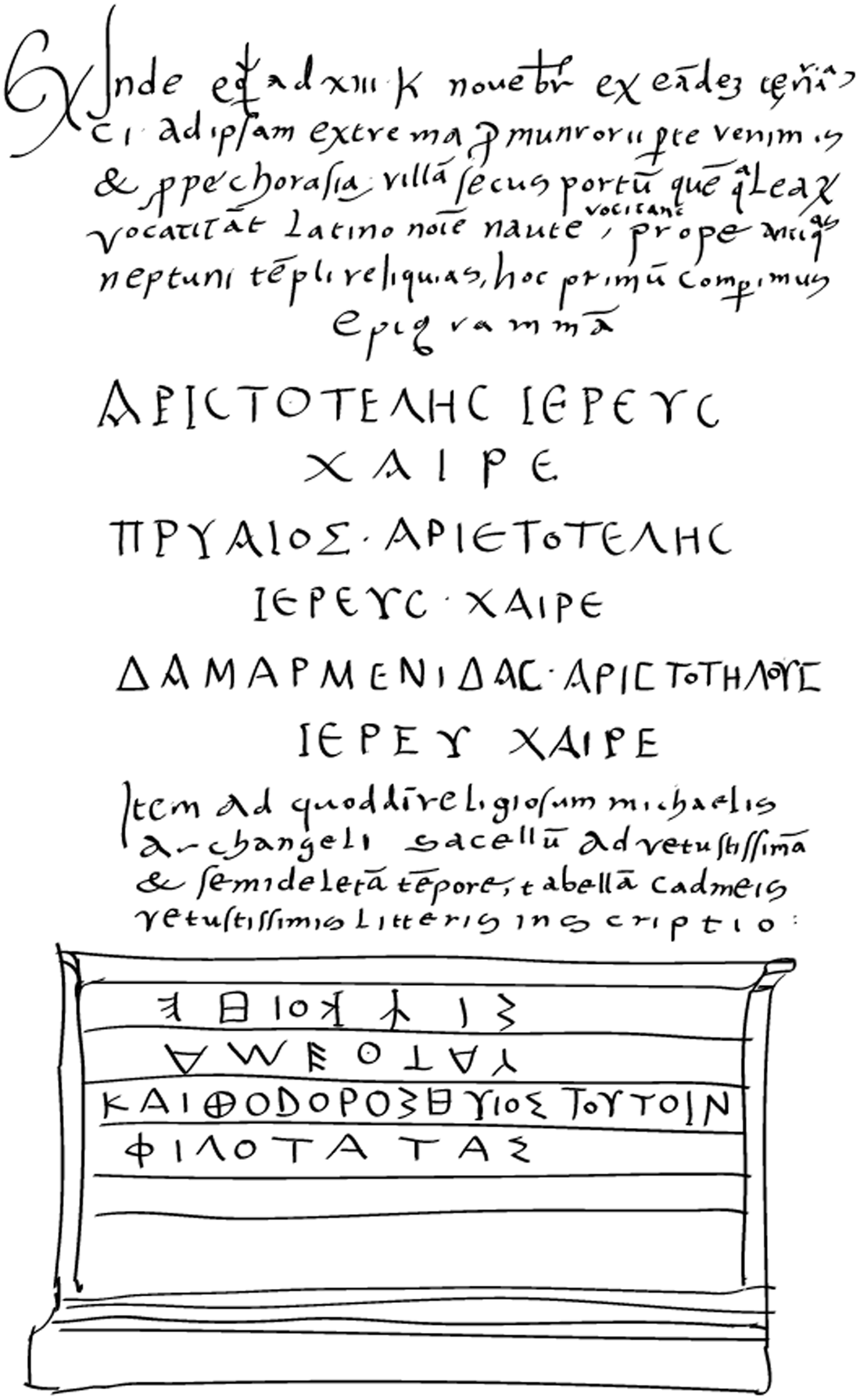

As mentioned above, Ciriaco also preserved the scripts. This is especially clear in the sylloge of 1437–40 made for Filelfo (fig. 3). There he differentiated, it seems, between the styles of the imperial Roman and early Christian inscriptions in his records. Later, he was similarly attentive to the various Greek scripts he encountered. For example, Ciriaco prefaced a copy of certain inscriptions he saw in a Peloponnesian village in 1447 thus: “We saw . . . marble bases of once noble statues, whose inscriptions, carved in Greek letters, I shall write down in their particular script.”Footnote 111 And, on the same trip, he observed in Porto Quaglio, “on a very old tablet, partially effaced by the passage of time, an inscription in very ancient Cadmaean lettering,” which he transcribed at the bottom of the page (fig. 5).Footnote 112

Figure 5. Ciriaco's records from Porto Quaglio, entered in his diary in 1447. My rendition of Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Trotti 373, fol. 116v.

Ciriaco was also keen to record fragmented inscriptions, which he faithfully copied using an ellipse to represent missing text. As far as I know, no fragmentary inscriptions are recorded in the Einsidlensis or the other medieval sylloges. By contrast, take, for example, Ciriaco's copy of a fragmentary monument in Merbaka in 1447 (figs. 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Ciriaco's records from Merbaka, entered in his diary in 1447. My rendition of Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Trotti 373, fol. 114v.

Figure 7. Inscribed monument decorating the Church of the Dormition of the Theotokos at Merbaka (Ayia Triada). Photo by Stelios Zacharias, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In each of these respects—the reproduction of capital letters and scripts and the indication of missing or illegible text—Ciriaco followed the example of earlier humanist sylloges. Poggio was the first and most significant to make such collections, and Ciriaco probably saw one of them. Now two copies of Poggio's sylloges survive, neither in his hand.Footnote 113 The earlier of the two was made by Niccolò Signorili in 1409.Footnote 114 Signorili's sylloge attends to the same elements prioritized by Ciriaco: fragmentary inscriptions are preserved, with missing text represented by ellipses, and the script is copied with some precision.Footnote 115

Early humanists studied such details for a number of reasons. One was historical curiosity, which depended on minute observations. For instance, in 1403, Salutati investigated the ancient name of Città di Castello. Following a series of clues in medieval texts, he deduced that it must have been called either Tyfernum or Tifernum.Footnote 116 He decided between the two thus: “I think that Tifernum should be written with an i and not with a pythagoric letter [y]. This point is made credible by the very ancient letters that I saw, taken from the marble stone that is in the house of the canons of this city.”Footnote 117

A similar approach was taken by Niccolò Niccoli some time before 1413, in composing De orthographia, in which he seems to have used inscriptions to make arguments about diphthongs.Footnote 118 His use of inscriptions is suggested by the fact that Guarino da Verona wrote an invective against him for presenting coins and marble remains as evidence.Footnote 119 Clearly, some humanists realized early on that inscriptions could be used as proof, and they were aware, therefore, of the importance of accurately recording their observations of material sources.

Humanists’ interest in script was not historical in nature—though its derivation could be seen as related to historical documentation. It stemmed from a practical need for clarity.Footnote 120 Petrarch had pronounced the prevailing book hand, the cramped gothic script, too difficult to read, and so he initiated a movement to find a more legible alternative.Footnote 121 Around the turn of the century, Niccoli and Poggio began examining the broad letters of ancient inscriptions as well as the Carolingian hand, which they saw exemplified in the Einsidlensis, among other manuscripts.Footnote 122 By 1408, Poggio had mastered the ancient Roman inscriptions’ majuscules and integrated them into the new humanist script.Footnote 123 The sylloges, both old and new, evidently served humanists as models for writing.

The sylloges also served in the creation of new inscriptions. Artists from Ghiberti (1378–1455) onward experimented in their sculptures and paintings with different scripts, which they adapted from the new humanist script and ancient inscriptions, as Millard Meiss has shown.Footnote 124 Notably, in 1463, Feliciano dedicated a collection of epigraphs to Mantegna.Footnote 125 New inscriptions were also crafted in cities to honor leading citizens, following the model of older inscriptions. Ciriaco, for instance, composed inscriptions for kings, dukes, bishops, and others throughout his life. For example, he wrote in 1445, “When we learned that his church [in Cydonia, Crete], which had collapsed from great age, had been restored by that excellent bishop [Luca Grimani] himself, we composed these Latin and Greek inscriptions for placement on the building itself.”Footnote 126

These changes to the medieval sylloge, including the reproduction of capital letters, scripts, and the indication of missing text, were the essential ones that Ciriaco inherited from Italian humanists on the peninsula. The others he developed himself in response to the particular culture he encountered in the eastern Mediterranean.

One specific change that Ciriaco introduced was to draw the inscribed monument. At least thirteen of his drawings of inscribed monuments are known.Footnote 127 As can be seen in figures 5 and 6, they were generally detailed and accurate. Embellishments are evident, and they are especially apparent in some of his drawings of other objects, but his accuracy overall is significant.

More and more of antiquity's physical appearance was entering the written record. With the material context of the inscription, both its script and monument, now preserved, the subject of the sylloge was no longer the text of the inscriptions alone but the objects themselves. They were objects that could be mined for details about provenance and historical context, as other scholars soon realized.Footnote 128 Through these innovations—both reproducing inscriptions’ particular scripts and drawing the monuments—Ciriaco and his contemporaries began to transform the practice of observing and recording inscriptions beyond its medieval origins. Ciriaco's observations were not limited to expert conversation, as they were for the urban elite. Nor were his records merely abstracted lists of texts, like the medieval sylloge. Rather, they became catalogues of artifacts.

Ciriaco's detailed work on inscriptions mirrors his investigation of other types of antiquities, such as fortifications, buildings, and walls. As Chatzidakis has shown, on these subjects, above all, Ciriaco developed the most sophisticated approaches to documenting artifacts, which foreshadow modern archaeological practices.Footnote 129 As with inscriptions, he was interested in minute details of the material of ancient masonry, for instance, and made drawings of them, even when they were neither complete nor spectacular.Footnote 130

Ciriaco's final advance on the study of inscriptions was his departure from the medieval sylloge as a medium. He did not restrict himself to a single manuscript collection, nor did he remain strictly devoted to the city of Rome. Instead, he copied inscriptions wherever he could find space for them as soon as he saw them. He compiled new sylloges. He copied inscriptions into his notebooks and diaries. He enclosed copies of them in his letters. And he crammed little lists of them into the margins of his books, next to the relevant passages of ancient texts. He had observed them in places all over Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. It was the vast scale and geographical scope that Ciriaco achieved that definitively transformed the study of inscriptions beyond its narrow medieval origins, making it an open-ended investigation of the Mediterranean world and its history.

The urban culture of Italy and the eastern Mediterranean was key to many of the elements that made Ciriaco's work revolutionary. As outlined in the first section of this article, Italian cities were full of curious individuals: curious about the lands they owned or wished to own, the precious goods and glorious buildings that were found in those places, and, not least, the antiquities scattered about them. Pragmatic concerns for greater dominion had spurred interest in some cases, while in others, the simple fact of long-term settlement had engendered a basic knowledge of the area. During Ciriaco's lifetime, and, of course, partly because of his interactions with locals, engagement with the land and its antiquities changed from tacit impressions, small-scale collections, communal observations, and conversations to systematic written accounts of them.

Tours of the grounds, guided by the model of the Christian sylloge, became essential to this turn. After learning of the Einsidlensis, Ciriaco focused his attention on ancient inscriptions, rather than other types of antiquities, and applied its system to all sorts of places. He compiled new sylloges, especially from material he saw in Dalmatia, Venice, and Padua, and Epirus, Achaea, Phocis, Boeotia, Euboea, Athens, and Sparta, as Edward Bodnar has deduced.Footnote 131 Ciriaco always walked with pen in hand on the tours his guides provided him, asking questions about the locations of antiquities and about the inscriptions in particular.

He circulated pages of his diaries and gave the new compilations he made as gifts not only to Filelfo (fig. 3) but to many others, such as the Contarini family.Footnote 132 Ciriaco also sent letters that included a handful of inscriptions at a time to friends, such as Bruni in Florence, Roberto Valturio in Ravenna, Melchiore Bandino in Candia, and Andreolo Giustiniani in Chios.Footnote 133 Poggio did the same with Niccoli on the peninsula.Footnote 134

These gifts and letters were desirable for new reasons. They did not necessarily support the supremacy of the papacy, as earlier sylloges had done. On the contrary, those devoted to Venice and its outposts served to demonstrate the illustrious history of those places, as well as their political prestige. Nor did the transcriptions merely serve the practical interests of modeling scripts or texts to create new inscriptions. Rather, they served a growing curiosity about the world. Part of that curiosity grew out of the humanist interest in the classical past and its different way of life, a subject into which the inscriptions gave insight. For example, in a letter to Bruni, Ciriaco wrote, “I chose to transcribe this Latin inscription I recently found in Athens for your most worthy consideration, Leonardo, most judicious of Latin writers, so that through it you might more readily see the great care and effort our ancestral princes of the Latin name took to restore the noblest cities, with immense foresight, reverence, and greatness of soul.”Footnote 135 The individuals named in the monuments’ texts served as moral exempla for the new world of a different, more virtuous way of living and also provided clues about the past.Footnote 136

Eastern Roman humanists had long since developed an empirical approach to antiquities, from which Italians learned. As Ruth Webb has argued, the rhetorical tradition of ekphrasis, in which art is described vividly, was important to Eastern Roman scholarship and was the form Manuel Chrysoloras followed in his famous Comparison of Old and New Rome of 1411.Footnote 137 He wrote, for example, that “all these scenes [of ancient victories depicted in sculpted reliefs] are crafted and expressed so that they seem to be living, and they can be identified by the inscriptions.”Footnote 138 Although this work was probably not widely known to Italians, since it was not translated into Latin until 1454, more learned figures such as Bruni probably knew it and may have discussed its general ideas with people like Ciriaco. Further study on this subject would be needed to draw more definite conclusions on the significance of ekphrasis.

Curiosity about ancient inscriptions also grew out of a broader Mediterranean sentiment, which was more general than that of humanists. The urban elite of the Mediterranean wished to know what there was abroad. This is especially clear from the development of drawing from observation, which shaped Ciriaco's depictions of inscribed monuments. Ciriaco drew a giraffe he saw in Egypt, for example, an image that became widely popular. Surviving letters attest to the purpose of its creation and its rather broad circulation. He gave a copy of it to a certain Marianus (probably after 1441), the Anconitan poet Andrea Stagi in 1442, the Veronese Giacomo Rizzini in the same year, the emperor Sigismund (probably around the same time), and one Andreolo Giustiniani in Chios in 1444.Footnote 139 In these letters the drawing is always described in the same way: it complements the detailed textual descriptions of the giraffe, which he provides along with the drawing, in order to convey the image vividly and accurately.

A sentence Ciriaco writes to Andreolo in 1444 is representative: “Today we have given to the most worthy emperor, and now to you your Beatitude, a likeness of it [the giraffe] that I made recently during our hunt, so that in our estimation, as far as possible, you have seen the living beast as we did, though you remain at your hearth and have not yet traversed the vast sea as we have in our journey.”Footnote 140 A representative response from Rizzini in 1442 echoes Ciriaco's enthusiasm for the effects of a good drawing: “Who, gazing on the giraffe that you recently gave me, is not held in admiration of it, and who does not remain enchanted with his eyes fixed on it?”Footnote 141

Ciriaco's drawings of monuments served a similar end. He discusses the drawings he made in the 1440s of the Parthenon, the temple at Cyzcius (and its inscription), and a Peloponnesian statue in similar terms, emphasizing the spectacular nature of the objects.Footnote 142 His drawings showed which antiquities remained and what their current condition was.

This kind of eagerness to see and know extraordinary places made the unprecedented geographical scope and scale of Ciriaco's work possible. Materially, it depended on the political circumstances that planted Italian urban elite across the sea, like frogs around a pond, but the written record could not have grown so precise without humanist insights or so expansive without the curiosity that developed among the urban elite. A primordial form of the republic of letters, which was devoted especially to the study of antiquities, and inscriptions in particular, was incipient in this Mediterranean community, which extended from Florence to Chios, at least. In it, observations were made and discussed both on the ground and in writing.

CONCLUSION

Unlike Minerva, antiquarian scholarship was not born fully formed. Some intellectual pursuits were, such as humanist historiography, as Eric Cochrane showed.Footnote 143 But this was not the case for early modern studies of material sources on the past. Since at least Momigliano, scholars have been swift to make generalizations about the movement, christening it antiquarian scholarship because of the clear resemblances between the works of Poggio, Ciriaco, Biondo, and the like, and those of the Enlightenment, such as the publications produced by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Tracing the line of development in this way has its merits, of course, but it reveals more about the later scholars, who imitated their predecessors, than it does about the first generation.

A closer look at the original sources of the first humanists reveals manifold developments intersecting with one another. The first humanists to study material antiquities assimilated different models from different traditions, and their works were fundamentally shaped by the political and social circumstances of the time. There was little about the investigation that was deliberate or fully clear, originally. The case of epigraphy suggests as much. We can speculate on its grounds that something similar is true of the other approaches—namely, of describing antiquities textually, drawing them, making material collections, and so on. The irregularity of their initial production and content is another clue in this direction.

It is clear, then, that neither classical precedent nor the new systematic humanism was the cause behind the turn to material sources or the study of inscriptions. Duncan MacRae has already shown, contrary to Momigliano, that there was no such thing as classical antiquarian scholarship.Footnote 144 And my own findings confirm from the other side of history that the first humanists did not rely on, nor even search for, a classical precedent to inform their studies of inscriptions. Instead, they looked to medieval traditions despite the commonplace accusation that the preceding period was a dark age.

A new culture had taken shape in the late medieval Mediterranean, one that was ripe for the discovery of antiquity. By Weiss's standard it was not a humanist culture, strictly. It was not made up of scholars who read texts systematically and looked for materials with which to complement them. There were such scholars, but they were the minority. Ciriaco himself barely fit this category. Rather, this new culture was made up primarily of wealthy, ambitious individuals deeply engaged in politics and commerce, who were cultured and curious in a basic way. Brian Maxson has expanded our notion of humanism to incorporate such people, whom he found in abundance on the Italian peninsula.Footnote 145 Evidently, they were also common in Dalmatia, the Levant, and Greece.

It was the social and geographical breadth of this Mediterranean culture, and its special customs relating to antiquities, that proved crucial to the emergence of epigraphy. The Italian urban elite was accustomed to traveling and observing the eastern Mediterranean and building their reputation in that volatile political context on the basis of their possession and knowledge of antiquities. Once humanists learned how to use the medieval sylloge as a tool to document antiquity, the Mediterranean community inspired new kinds of discoveries. More and more people began to record inscriptions, among other antiquities, and to exchange copies of them across the sea. None compared in their zeal to Ciriaco, however, who learned from the greatest number of people and recorded the largest collection yet.

APPENDIX: Ciriaco's Guides