Excessive weight substantially increases the risk of a variety of chronic diseases including cancer, CVD and diabetes( Reference Stewart, Tikellis and Carrington 1 ), and accounts for over 2 million deaths each year( Reference Lopez, Mathers and Ezzati 2 ) and more than 30 million disability-adjusted life years( 3 ). While evidence regarding the effectiveness of obesity prevention initiatives is equivocal( Reference Livingstone, McCaffrey and Rennie 4 ), there have been calls from international organisations( 5 ), professional associations( 6 ), academic experts( Reference McCormick and Stone 7 , Reference Gill, Baur and Bauman 8 ) and the community( Reference Lavery 9 ) for governments to take decisive action to mitigate the adverse impacts of obesity. Indeed, across the globe, governments have developed policy, set obesity prevalence targets( Reference Crombie, Irvine and Elliott 10 ) and are implementing obesity prevention initiatives( Reference Fussenegger, Pietrobelli and Widhalm 11 ).

Similar to efforts to reduce other chronic disease risk factors in the 1980s and 1990s( Reference Nissinen, Berrios and Puska 12 , Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 ), community-based prevention programmes that attempt to address multiple determinants of obesity through multi-component population-wide strategies are frequently recommended( 14 ). Comprehensive evaluation of such initiatives is recommended to ensure that conclusions regarding programme effectiveness are valid, to provide an understanding of why and how a programme may have succeeded or failed, and to facilitate programme improvement, policy development and service investment( Reference Ovretveit 15 , Reference de Zoysa, Habicht and Pelto 16 ). As such, programme evaluation is recognised as a key component of best-practice community-based obesity prevention practice( Reference King, Gill and Allender 17 ).

In order to improve the rigour of future community-based obesity prevention programmes to better inform policy makers and practitioners, the aim of the present paper was to review the methodological literature regarding evaluation methods recommended for complex public health interventions broadly, and community-based interventions specifically, and to critically reflect on the evaluations of contemporary community-based obesity prevention programmes in the context of such recommendations. In doing so, we sought to outline a number of issues we believe represent significant impediments to the quality of community-based obesity prevention programme evaluation and offer some possible ways in which such impediments may be addressed.

Method

A review of the literature was performed in January 2011 to identify: (i) key elements of rigorous evaluations of community-based interventions from the research methods literature and from methodological reviews of previous community-based chronic disease prevention trials; and (ii) the evaluation methods used in community-based obesity prevention programmes.

Guidance regarding rigorous evaluation of complex interventions

To identify recommended evaluation methods for community-based interventions we reviewed: (i) the UK Medical Research Council's guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions( 18 ); (ii) recommendations from an expert group on research designs for complex, multilevel health interventions sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ); and (iii) selected research design and evaluation texts( Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 – Reference Nutbeam and Bauman 22 ). We also examined reviews of methodological issues of past community-based health intervention trials( Reference Nissinen, Berrios and Puska 12 , Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 , Reference Atienza and King 23 – Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 ).

Community-based obesity prevention programmes

We employed systematic methods to identify previous community-based interventions. While there have been various definitions of what constitutes a community-based intervention( Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 , Reference McLeory, Norton and Kegler 26 ), those which characterised a ‘community’ along geographical boundaries such as cities, villages or regions are most common( Reference Atienza and King 23 ) and are the subject of discussion in the present paper. As such, to be eligible for inclusion in the review, an obesity prevention intervention must have: (i) been implemented on a population basis across a defined geographic region (such as a town or city); (ii) included a measure of weight status; and (iii) been published in English and in a peer-reviewed journal. Published reports of evaluation designs or study protocols of incomplete trials were also included. Community-based interventions primarily focusing on reducing chronic diseases such as CVD or diabetes where obesity prevention was one of a number of risk factors targeted were excluded.

To identify such programmes, the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Google Scholar were searched by one reviewer (L.W.) for articles published between 1990 and 2010. The search strategy for MEDLINE is described in the Appendix and was modified for other databases (a full search strategy for each database is available on request from the corresponding author). Reference lists of systematic reviews including the Cochrane review of interventions for the prevention of obesity( Reference Summerbell, Waters and Edmunds 27 ) and narrative reviews or editorials on the issue of community-based obesity prevention interventions( Reference Friedrich 28 – Reference Huang and Story 30 ) were also searched.

Research synthesis

Information from community-based obesity prevention trials and texts providing recommendations regarding their evaluation was synthesised narratively in terms of issues considered to be important in the conduct of rigorous evaluations of community-based interventions, including( Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 , 18 , Reference Nutbeam and Bauman 22 , Reference Atienza and King 23 , Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 , 31 , Reference Gilligan, Sanson-Fisher and Shakeshaft 32 ):

-

1. ethical and scientific conduct and reporting;

-

2. research design;

-

3. data collection;

-

4. measures; and

-

5. analysis.

Results

Articles retrieved and included

The electronic database search yielded 1197 citations. Following screening of titles and abstracts, full texts of thirty-three articles were reviewed. Of these, twelve were not population-wide community-based interventions, five targeted a broad range of chronic disease risks, two did not include a measure of weight status, one targeted weight loss rather than prevention, and the intervention and evaluation methods of two trials were still under development or yet to be reported. These trials were deemed ineligible. The remaining eleven articles( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 – Reference Romon, Lommez and Tafflet 43 ) described ten eligible community-based obesity prevention initiatives (Table 1).

Table 1 Evaluation characteristics of the population-wide community-based obesity prevention programmes included in the present review

LGA, local government areas; SES, socio-economic status; WC, waist circumference; BP, blood pressure; PA, physical activity; %BF, percentage body fat.

Ethical and scientific conduct and reporting

Research ethics

While impropriety has not been raised as an issue in the evaluation and reporting of previous community-based obesity interventions, all programme evaluations are recommended to begin with consideration of standards of ethical and scientific conduct and reporting. Ethics approval and monitoring of study procedures by independent ethics committees (or Institutional Review Boards) and adherence to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html) are an essential part of programme evaluations and a prerequisite for publication in most peer-reviewed journals. The American Evaluation Association's Guiding Principles for Evaluators( 31 ) also provides guidance on proper professional conduct for evaluators and covers issues of competence, integrity, honesty, respect for people and responsibilities for general public welfare.

Trial registration

The UK Medical Research Council recommends that trials are reported regardless of the ‘success’ of the intervention( 18 ). Given this, evaluators of community-based obesity prevention programmes should be aware of the potential for political and programme stakeholder interests to influence the proper conduct and reporting of community programme evaluations. Research has found that stakeholder interests can influence evaluation design decisions of programme evaluators( Reference Azzam 44 ) and can suppress( Reference Yazahmeidi and Holman 45 ) or pressure evaluators to misrepresent study findings( Reference Morris 46 ). The interests or inherent biases of obesity researchers have also been suggested to lead to misleading interpretations of research studies( Reference Cope and Allison 47 ). Prospective trial registration is a scientific convention that can help protect against such influence by requiring evaluators to document specific details of the evaluation design, intended sample, measures and planned analysis on a publically accessible database prior to the research evaluation taking place (Clinical Trial Registration). The requirement for registration of intervention trials was adopted by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in 2005 following the establishment of the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform( Reference DeAngelis, Drazen and Frizelle 48 ). While a number of current and planned community-based obesity prevention programmes have been registered with an internationally recognised trial registry( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 , Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bolton and Haby 41 ), the extent to which unregistered evaluations adhered to planned evaluation protocols or selectively reported trial outcomes is unable to be assessed. For trials which have utilised a community-based participatory approach, such as the Pacific OPIC Project (Obesity Prevention In Communities)( Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ), prospectively describing trial methods on a register may represent a considerable challenge given evolving research methods owing to the shared decision making and collective engagement of community members and organisational representatives in each research phase( Reference Viswanathan, Ammerman and Eng 49 ). Nevertheless, documenting changes in research methods in trial registers over the course of the study as they occur and providing justifications for amendments in trial procedures may reduce the risk of selective reporting or other reporting biases.

Scientific reporting

The reporting of trial findings consistent with agreed standards, such as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for randomised evaluation designs or the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement for non-randomised evaluation designs, is a requirement of many of the leading public health and general medical journals. Reporting of trial outcomes consistent with such standards has been a feature of some past published community-based obesity prevention evaluations( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 , Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 ). Greater adherence to such standards improves transparent and consistent reporting of research trials( Reference Plint, Moher and Morrison 50 ) and may facilitate subsequent synthesis of trial outcomes by systematic reviews.

Protocol publication

A reported limitation of previous community-based health promotion programmes has been that a lack of sufficient documentation of intervention and evaluation strategies and procedures( Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 ) has limited the ability to interpret study outcomes. Given word limit restrictions placed by non-electronic journals on submitted papers, the capacity to report the detail required to sufficiently describe evaluations of complex interventions such as community trials has been constrained. Two recent developments represent opportunities to redress this limitation. First, publication of evaluation protocols represents a mechanism whereby such detailed information is able to be provided. Publication of such protocols also serves as a further mechanism to address scientific integrity of subsequent reporting of results through a public statement of evaluation intent. Second, publication of protocols and/or results in electronic open access journals (which do not have space restrictions) or housing additional intervention or evaluation information in other publically accessible websites has been recommended( Reference Wolfenden, Wiggers and Tursan d'Espaignet 51 ) and employed successfully by some existing evaluations of community-based obesity prevention programmes( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bolton and Haby 41 ).

Selection of research design

Previous evaluations of community-based obesity prevention interventions have employed uncontrolled pre–post( Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ), post-test only comparison( Reference Romon, Lommez and Tafflet 43 ) or quasi-experimental designs with( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 – Reference Samuels, Craypo and Boyle 35 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 – Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bolton and Haby 41 , Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ) and without comparison conditions( Reference Cheadle, Schwartz and Rauzon 36 , Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ). Such designs are vulnerable to a variety of biases, particularly the influence of secular trends or confounding( Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 ). The use of more internally valid research designs, such as those employing methods of random allocation (experimental designs), or efforts to strengthen the internal validity of more pragmatic quasi-experimental evaluation designs will provide greater confidence in the extent to which any observed effects can be attributed to a programme( 18 , Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 , Reference Nutbeam and Bauman 22 ).

Randomised experimental designs

Randomised and cluster randomised controlled trials. Randomised (cluster) controlled trials are considered to represent the most internally valid evaluation design and have previously been used to assess the impact of cardiovascular and cancer risk factor community-based interventions( Reference Hancock, Sanson-Fisher and Redman 24 , 52 ). A randomised controlled trial may be particularly valuable in innovation testing phased evaluations( Reference Nutbeam and Bauman 22 ). Ethical considerations, costs and logistical difficulties in randomising and intervening in large geographically separated communities, however, are well documented as impediments to the use of such experimental trial designs in community-based prevention programmes( Reference Sanson-Fisher, Bonevski and Green 53 ). Nevertheless, both the UK Medical Research Council( 18 ) and the recommendations from an expert group convened by the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend the use of randomised controlled trials for programme evaluation whenever feasible( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ). Generally, a sample of at least ten intervention and ten control communities is suggested as a minimum number of sites for the conduct of experimental trials of community-based interventions( Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 ).

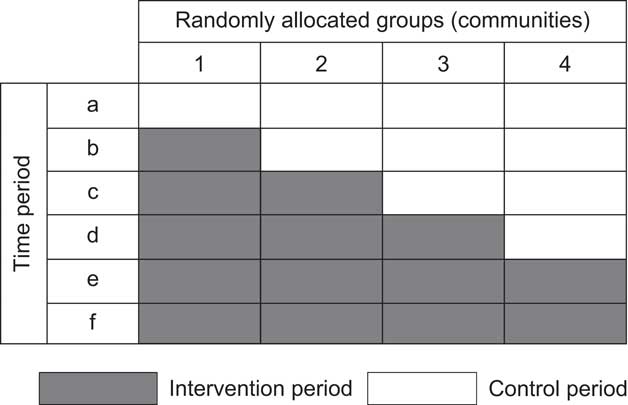

Stepped wedge cluster randomised trial. A stepped wedge cluster randomised trial may overcome a number of constraints to the conduct of traditional randomised and cluster randomised community-based trials( Reference Mdege, Man and Taylor 54 ). A stepped wedge design involves measurement of trial outcomes (i.e. weight status) being repeatedly undertaken simultaneously across a number of clusters (i.e. communities) over a period of time. In the context of such measurement, the delivery of the intervention occurs sequentially across communities, the order being randomly determined( Reference Hussey and Hughes 55 ). Comparisons are made between groups at the intervention section of the wedge (see Fig. 1) as well as within groups before and after the intervention. Advantages of the stepped wedge design for community-based prevention interventions include: the receipt of the intervention by all communities (overcoming ethical concerns regarding withholding intervention); the congruence of the design with intervention capacity constraints and typical schedules of programme rollout; the requirement of fewer clusters than a conventional randomised cluster trial; and the capacity of the design to detect and control for underlying trends and time effects. While the design requires repeated assessment of outcomes (e.g. weight status) which may be expensive and pragmatically challenging, the use of routinely collected weight status data – such as that utilised to assess the impact of Romp & Chomp and the Healthy Living Cambridge Kids obesity prevention programmes( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 , Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ) – represents one approach to achieving these benefits at relatively low cost.

Fig. 1 Illustration of a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial

Quasi-experimental designs

Regression discontinuity. Where programme funding permits the use of large numbers of communities but ethical or political considerations deem randomisation not acceptable, regression discontinuity designs have been recommended as a potentially attractive alternative to experimental randomised designs( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 , Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 ). Together with randomised trials, regression discontinuity designs represent the only other trial design which can provide an unbiased estimate of intervention effect( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 , Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 ). Rather than random assignment, in regression discontinuity designs researchers assign communities (or participants) to intervention or comparison conditions based on their exceeding a designated cut-off point on a pre-intervention assignment variable (e.g. BMI). A regression line through such an outcome variable which discontinues at the point of assignment for control group communities is taken as evidence of an intervention effect. The design may be particularly useful for community-based obesity programmes targeting socio-economically disadvantaged groups, where communities are assigned to receive an intervention based on their score on a measure of disadvantage. Owing to co-linearity between the assignment and outcome variables, however, regression discontinuity designs require substantially more research participants (or communities) compared with a similarly powered randomised trial( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ).

Interrupted time series. In a time series evaluation of a community-based obesity intervention, repeated measures of weight status are required for a period prior to, during and following intervention delivery in one or more community. Comparisons are made between the change in level or slope of the outcome prior to and following the intervention to assess intervention effect( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ). The addition of comparison communities which do not receive the intervention improves the internal validity of the design. Like the stepped wedge cluster randomised trial design, the repeated measures allows for control of trends and time effects and is typically a more rigorous evaluation design than before-and-after trial designs( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ). While the use of routinely collected weight status data from institutions such as health services would permit a relatively low-cost evaluation using this design, the lack of such obesity surveillance data in most countries and communities has been previously identified as a significant impediment to its use( Reference Swinburn and de Silva-Sanigorski 29 ).

Controlled and uncontrolled pre–post trials. Pre–post designs, where outcome assessments are taken at a single point in time prior to and following the delivery of an intervention, represent the most commonly utilised evaluation design in community-based interventions. Such designs, however, face a number of threats to internal validity( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ). Where the inclusion of controlled designs is feasible, programme evaluators should seek to maximise the number of intervention and comparison communities to help account for secular trends( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 , Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 ). Stratifying or matching communities in such designs based on factors known to be closely associated with population weight status is also recommended to reduce the risk of selection bias and to maximise statistical power by increasing precision( Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 , Reference Atienza and King 23 ). Identifying communities with comparable characteristics, however, represents a considerable challenge( Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 ). Even with large numbers of communities, non-randomised pre–post designs should not be relied upon alone to infer casual inference( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 ).

With the exception of the Health Promoting Communities: Being Active Eating Well initiative( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bolton and Haby 41 ), community-based obesity prevention interventions reviewed in the present paper that have employed a controlled design to date have not employed formal stratification or matching techniques. Further, a number of such obesity prevention initiatives( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 – Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 , Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ) selected intervention communities on the basis that they had existing infrastructure to facilitate intervention delivery, unlike comparison communities. Such known non-equivalence between groups on factors such as community capacity or infrastructure represents a significant threat to the internal validity of trial findings in principle, as such factors are difficult to measure reliably and adjust for in analyses of programme outcomes( Reference Simmons, Reynolds and Swinburn 56 ).

Strengthening quasi-experimental designs. As a possible addition to all quasi-experimental designs, evaluators can maximise the internal validity of programme evaluations through the use of non-equivalent dependent variables( Reference Mercer, DeVinney and Fine 19 , Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell 20 ). For example, if a community-based intervention is delivered to all students attending government schools only, assessments of weight status of students in government and non-government schools in the intervention communities pre and post intervention delivery could be conducted. As students of both schools are likely to be subject to non-intervention factors in the community which may impact on weight status (such food marketing or macro-economic policies or events) but only those attending government schools are exposed to the intervention, a differential impact in the change in weight status over time would provide greater evidence of an intervention effect. A second strategy to enhance the internal validity of quasi-experimental designs is via assessment of a dose–response relationship between exposure to intervention activities and trial outcome (e.g. weight status). Dose–response analyses have been found to be a valuable feature of past community-based CVD risk factor intervention( Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 ). Neither strategy, however, appears to have been employed as an adjunct to evaluations by the community-based obesity prevention programme evaluations employing quasi-experimental designs included in the present review.

Data collection

Survey methods

Obesity prevention interventions have typically utilised survey methods to assess intervention outcomes. Instances where survey participation rates are low, attrition is high or either rate is different between groups limit the validity of inferences regarding intervention effects.

Research participation. Despite high anthropometric survey participation rates among New Zealand( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 ) and French( Reference Romon, Lommez and Tafflet 43 ) obesity prevention programmes, participation rates for programmes in the USA and Australia have typically ranged between 29 % and 58 %( Reference Economos, Hyatt and Goldberg 38 , Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 ). Research suggests that obese persons may be less likely to participate in research requiring anthropometric assessments( Reference Mellor, Rapoport and Maliniak 57 ). Examination of the potential for selective non-participation bias by comparing the characteristics of participants with non-participants( Reference DeAngelis, Drazen and Frizelle 48 ) has not, however, been reported in any obesity prevention programme included in the present review. Identifying non-response bias may be particularly important in repeat cross-sectional evaluations of intervention effect (where independent cross-sectional samples are drawn from communities pre and post intervention), as small changes in the likelihood of participation in overweight participants at follow-up could result in artefactual post-intervention reductions in estimated obesity prevalence. As a crude illustration; assuming a pre-intervention prevalence of child overweight of 25 % (250/1000), a relative 20 % reduction in the likelihood of participation of overweight persons at post-intervention assessments would reduce post-intervention prevalence to 21 % (200/950). Hypothetically, such changes in the propensity of overweight child participation may be an unintended consequence of the intervention itself, if intervention exposure increases perceived obesity stigma and reduces children's interest in participation. Such reductions could be misinterpreted as a public health intervention success.

Evaluation texts and methodological reviews recommend that evaluators seek to reduce the risk of non-response bias by employing intensive recruitment strategies to maximise study participation, such as the pre-notification and promotion of study participation, endorsement of the research by credible individuals or organisations, participation incentives and multiple follow-up reminders( Reference Treweek, Pitkethly and Cook 58 , Reference Wolfenden, Kypri and Hodder 59 ). For trials that include a comparison condition, reporting participation rates among both intervention communities and comparison communities would allow an assessment of the potential risk of differences in non-participation between groups. More rigorous strategies, such as the recording and analysis of information regarding the weight status of non-participants, would provide more compelling evidence regarding the possible influence of non-participation, if permitted by ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards. For example, Booth and colleagues( Reference Booth, Okely and Denney-Wilson 60 ) describe a feasible, inexpensive and valid means of collecting weight status information of children not participating in school-based assessments of height and weight by having classroom teachers match the morphology of such children to those of participants.

Research attrition. Research attrition can threaten the internal and external validity of a community-based intervention evaluation if the characteristics of participants not providing follow-up data differ from those who do, and if the characteristics of participants are dissimilar between intervention and comparison groups. Such differences can lead to over- or underestimates of intervention effect( Reference Barry 61 ). With the exception of the Be Active Eat Well programme, participant attrition (loss to follow-up) among child obesity prevention programmes with a cohort design in the present review ranged from 25 % to 45 %( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Samuels, Craypo and Boyle 35 , Reference Economos, Hyatt and Goldberg 38 , Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ) and differed substantially between groups in the case of the Shape up Somerville programme (intervention 39 %; comparison 25 %). Even when loss to follow-up is small and not differing significantly between groups, as was the case for the Be Active Eat Well initiative (approximately 16 % loss to follow-up per group), the potential for bias to influence study findings remains present. For example, in that trial 34 % of study withdrawals in the intervention group were due to parental concern regarding their child's self-esteem following weight assessment; a reason for withdrawal which was not cited at all for children in comparison communities. Two of the reviewed cohort studies formally examined the potential for bias due to differences between participants and those lost to follow-up as recommended( Reference DeAngelis, Drazen and Frizelle 48 , Reference Barry 61 ). The Healthy Living Cambridge Kids initiative reported that participants who did not provide follow-up data were more likely to be older, Asian and less likely to pass fitness tests( Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ). Project APPLE however found no meaningful differences between participants and those lost to follow-up( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 ).

Similar to those strategies to maximise study participation, evaluators should seek to employ intensive strategies to minimise study attrition such as through offering incentives, alternative locations for data collection and repeat reminders via mail and telephone( Reference Davis, Broome and Cox 62 , Reference Booker, Harding and Benzeval 63 ), reporting attrition rates by group( Reference DeAngelis, Drazen and Frizelle 48 , Reference Barry 61 ), and attempting to formally assess and control for bias due to study attrition in analyses.

Routinely collected institutional databases

Given the cost and feasibility challenges of collecting survey data, the use of routinely collected data such as health services records has been suggested as an inexpensive alternative for programme evaluation that does not require the development of new data collection systems and methodologies, often allows for comparisons with other regions or jurisdictions, can be used retrospectively and may be less likely to be subject to bias due to non-consent( Reference Kane, Wellings and Free 64 , Reference Breen, Shakeshaft and Slade 65 ). Despite these potential benefits, a number of limitations exist regarding the use of routinely collected data for evaluating public health interventions, including reliability between recording personnel, changes in data recording classifications, recording practices and systems, and limited population representativeness( Reference Kane, Wellings and Free 64 ). While evaluation of obesity programmes using such data needs to be mindful of these limitations, routinely collected information has a capacity to provide a valuable source of data for community-based obesity programme evaluations, particularly where they are accessed by a large proportion of the target population. For example, routinely collected BMI data were available from maternal and child health services in Victoria, Australia for approximately 60 % of all children of pre-school age and were used to evaluate the Romp & Chomp programme( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 ). Similarly, height and weight data routinely collected annually as part of the physical activity curriculum were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the Healthy Living Cambridge Kids initiative( Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ).

Outcome, impact and process measures

While a number of programme evaluation frameworks exist, the inclusion of measures which assess the outcome of the intervention (as specified by the programme aim), programme impacts on intermediary factors (typically described as part of programme objectives), intervention processes and context are most frequently recommended by evaluation texts and reviews of past cardiovascular community-based interventions( 18 , Reference Nutbeam and Bauman 22 , Reference Hancock, Sanson-Fisher and Redman 24 , Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 , Reference Hawe, Shiell and Riley 66 ). Importantly, the selection of evaluation measures should also be guided by programme logic models of how an intervention is intended to produce the intended intervention effect.

Outcome

Weight status. Given the limitations of self-reported measures of weight status( Reference Gorber, Tremblay and Moher 67 ) and the potential for such reports to be reactive to assessment( Reference Atienza and King 23 ), objective measures of would appear important in programme evaluations looking to examine the effect of a community-based intervention on population adiposity. BMI is the most widely utilised measure of weight status in previous studies( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 – Reference Romon, Lommez and Tafflet 43 ) and represents a relatively inexpensive and feasible measure of adiposity( Reference Livingstone, McCaffrey and Rennie 4 ). To provide information regarding changes in both body and fat composition, additionally assessments of waist circumference and skinfold thickness have been recommended, particularly as interventions including physical activity promotion can actually increase lean body mass and reduce adiposity without any change in BMI( Reference Livingstone, McCaffrey and Rennie 4 ). Such assessments should be conducted and reported in accordance with standard measurement protocols to reduce measurement error and to facilitate comparison across trials and data pooling in meta-analyses.

Adverse events. In order to evaluate the merit of a community-based intervention to prevent obesity, both the benefits and adverse effects of the intervention need to be considered. As such, potential harms which may arise from community-based interventions should be hypothesised and assessed as part of programme evaluations( 6 , 18 , Reference Roberts 68 ). Despite a few exceptions, assessment of harms has largely been overlooked in previous or planned community-based obesity prevention intervention evaluations included in the present review. The Be Active Eat Well child obesity programme was the only programme which explicitly included measures of harm such as the prevalence of underweight, weight loss attempts, weight-based teasing and unhappiness( Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 ). Similarly, assessments of the impact of the Pacific OPIC Project community interventions will include assessments of perceived body image (at least in a sub-sample of participants)( Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ). While individual measures of intervention harm are important, the potential adverse impacts at the setting or community level should also be considered by evaluators. For community safety, the use of committees (which include representatives from the community) to monitor adverse intervention effects and enforce ‘stopping rules’ in instances where adverse events exceed an acceptable level has been suggested as important( Reference Hawe, Shiell and Riley 66 ).

Impact

Healthy eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. As weight status changes are mediated by dietary improvements to reduce excessive energy intake and/or increased physical activity to increase energy expenditure, assessments of these behaviours can enhance the internal validity of programme evaluations and provide evidence of the mechanism behind any intervention effect. For example, greater confidence of an intervention effect would be characterised by an inverse association between weight status and healthy eating and physical activity.

In their assessment of healthy eating and physical activity, most obesity prevention programme evaluations rely on brief self-reported measures which are vulnerable to social desirable responding( Reference Livingstone, McCaffrey and Rennie 4 ). Only a few trials included in the present review indicated that such measures had been previously demonstrated to be valid or reliable( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 , Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 ). While short item questionnaires may represent the most feasible method to assess changes in broad dietary or activity patterns, such items represent crude measures and often are not sufficiently sensitive to detect small but meaningful changes at a population level. Indeed, in community-based programmes, these self-reported measures have been found to contradict objective measures. In the APPLE Project, for example, self-reported physical activity among children in intervention communities decreased significantly relative to control community children at the 1-year follow-up, in contrast to accelerometry assessments which found significantly increased counts among intervention community children over the same period( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 ).

The use of valid tools is key to robust programme evaluations. A number of papers have been published providing guidance to programme evaluators regarding the selection of measures to assess physical activity and nutrition in the context of purpose, capacity, skill and resource constraints( Reference Magarey, Watson and Golley 69 – Reference Sirard and Pate 71 ). In principle, obesity intervention programmes should seek to employ the most rigorous behavioural assessments which such constraints allow. The use of objective measures of physical activity such as accelerometry or fitness tests employed by previous interventions( Reference Taylor, Mcauley and Williams 33 , Reference Samuels, Craypo and Boyle 35 , Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ) or more rigorous dietary assessments such as 24 h food recall methods may be feasible for interventions with a small sample. For larger trials, the inclusion of such assessments on a sub-sample of the population could be considered in addition to the broader use of validated self-reported physical activity or food frequency questionnaires as a means of measurement triangulation.

Community environment. Community-based interventions often seek to reduce population adiposity through modifying community environments, such as the availability or accessibility of healthy foods or physical activity opportunities in key community settings (i.e. schools). For these interventions, community environmental characteristics which are the target of intervention represent important mediating variables and programme impacts in their own right( Reference Huang and Story 30 ). While a number of trials in the present review have assessed community environments as part of programme evaluations, most have not reported the validity of the methods used to do so( Reference Samuels, Craypo and Boyle 35 – Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 , Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer 39 , Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bolton and Haby 41 , Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ). The psychometric properties of a number of tools to assess obesogenic characteristics of the home (e.g. family eating routines), child care (staff prompting child activity) and neighbourhood environments (availability of physical activity facilities)( Reference Benjamin, Neelon and Ball 72 – Reference Cerin, Saelens and Sallis 74 ) have recently been published and their use would greatly strengthen the quality of future evaluations( Reference Gattshall, Shoup and Marshall 75 ). To our knowledge, however, there remains a lack of validated instruments for assessing other key community settings such as schools. The development of valid tools suitable for population-wide assessments of community settings and organisations would be particularly beneficial for programme evaluators and should be considered a research priority for the field.

Given the cost and complexity of evaluating individual health behaviour risks or chronic disease conditions noted in previous community-based health promotion programmes, the use of community-level environmental indicators has been proposed as a more feasible and cost-effective alternative when significant resource constraints exist( Reference Cheadle, Schwartz and Rauzon 36 , Reference Cheadle, Sterling and Schmid 76 ). The use of community environment measures in this way would require the availability and selection of valid measures of environmental characteristics known to be associated with population overweight and obesity, healthy eating or physical activity. Some simple and objective environmental proxy measures already exist. For example, grocery store shelf space has previously been found to reflect changes in some community dietary indicators with similar power to individual surveys at one-tenth of the cost( Reference Cheadle, Psaty and Wagner 77 ).

Process

Measures of the extent to which the intervention has been delivered, its reach and variability, often termed process evaluation, are recommended by the UK Medical Research Council as an important means of assessing intervention fidelity and exposure in complex interventions( 18 ). Process evaluation can also provide insight into why and how an intervention worked, or failed, and how it may be improved( 18 , Reference Oakley, Strange and Bonell 78 ). Process evaluation should be conducted to the same methodological standard and reported as thoroughly as assessments of intervention outcomes( 18 ). Process evaluations reported as part of planned or previous community-based obesity prevention evaluations have varied in the extent to which they have assessed intervention delivery, reach or dose( Reference Taylor, McAuley and Barbezat 34 , Reference Cheadle, Schwartz and Rauzon 36 – Reference Chomitz, McGowan and Wendel 40 ). Among the more comprehensive process evaluations have been the Romp & Chomp and Be Active Eat Well initiatives that were guided by explicit programme logic models and assessed exposure of the community to the intervention through changes in community capacity and organisational policies, practices or environments( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Robertson and Nichols 79 , Reference Simmons, Sanigorski and Cuttler 80 ). The lack of quality process information, particularly that related to intervention reach and dose, has previously been criticised as an impediment to the interpretation of community-based obesity prevention interventions( Reference Swinburn, Bell and King 81 ).

Context

The effectiveness of community-based interventions is undoubtedly influenced by the social, political and organisational contextual factors occurring at the time of implementation. A common criticism of process evaluation is that it presupposes and mechanistically assesses specified intervention components( Reference Hawe, Shiell and Riley 66 ). While this has merit, it ignores other contextual factors which could operate as effect modifiers. As such, the UK Medical Research Council recommends that, in addition to measurement of intervention process, the evaluation of complex interventions assesses, monitors and documents important changes in community context over the life of the project( 18 ). The California Endowment's Healthy Eating, Active Communities Program( Reference Samuels, Craypo and Boyle 35 ) explicitly states an intention to collect and synthesise context data via interviews, surveys and focus groups with community members, programme stakeholders and policy makers. While not stated as a context evaluation, other initiatives included in the present review collected and reported context information, such as other interventions occurring in study communities prior to or during intervention implementation, or changes in media activity and resources contributed by local agencies( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 ). As context evaluation is a developing science, little explicit guidance is available regarding what and how such information should be collected and utilised.

Analysis

Selection of the analytical procedure to assess the impact of a community-based approach to obesity prevention should, of course, be guided by the evaluation design( 18 ). As communities are typically the unit of analysis when assessing the effectiveness of community-based interventions, the use of generalised linear mixed models (also referred to as multilevel models, random-effects models, hierarchical linear models or covariance component models) is often most appropriate( Reference Atienza and King 23 ). Such analytical techniques account for intra-class correlation and allow for individual- and community-level influences to be examined simultaneously. Encouragingly, trials included in the present review employed such techniques and avoided unit of analysis errors previously documented in the obesity literature( Reference Livingstone, McCaffrey and Rennie 4 ).

Methodological reviews of previous community-based chronic disease prevention interventions have attributed modest intervention impacts, in part, to high rates of population migration into and out of intervention and comparison communities, or to inconsistent intervention exposure, diluting the intervention effect( Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 , Reference Gilligan, Sanson-Fisher and Shakeshaft 32 ). Such factors also represent a risk to evaluations of community-based obesity prevention programmes. The Shape Up Somerville child obesity prevention programme, for example, reported that 27 % of children had moved out of intervention or comparison communities within the first 12 months of the initiative( Reference Economos, Hyatt and Goldberg 38 ). Variable intervention implementation has also been reported( Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremmer 37 ). Two supplementary strategies may be useful in managing issues of intervention exposure when describing intervention effects in a community. First is a plausibility analyses, whereby comparisons are made between those receiving the intervention and those who did not after adjusting for confounders( Reference Victoria, Habicht and Bryce 82 ). The second is a dose–response analyses where the effect of the intervention is examined according to the level of exposure to the intervention( Reference Nissinen, Berrios and Puska 12 , Reference Swinburn, Bell and King 81 ). Despite the usefulness of such analyses, they have not been utilised in any of the trials included in the present review. Considering issues of intervention exposure, however, children residing within intervention communities but attending school outside the region will be excluded in the analysis of intervention effects of the Fiji OPIC initiative( Reference Swinburn, Pryor and McCabe 42 ).

Discussion

The findings of the present review illustrate that there is opportunity for greater cross-disciplinary learning from the evaluation experiences of past community-based chronic disease risk factor interventions( Reference Nissinen, Berrios and Puska 12 , Reference Merzel and D'Afflitti 13 , Reference Pirie, Stone and Assaf 25 ) and scope to improve the rigour of community-based obesity prevention interventions. Important methodological limitations apparent in a number of trials included in the present review, particularly in trial design and measurement, represent considerable impediments to inferences of causal attribution. Efforts to improve the rigour of future community-based interventions are therefore warranted.

Internationally, government and non-government organisations invest considerable sums in community-based initiatives to prevent excessive weight gain, often in the absence of – or with insufficient funding for – rigorous programme evaluation( Reference Swinburn, Bell and King 81 ). Quality evidence regarding the effects of community-based interventions is required to assess the community benefit of such expenditure, to help maximise future investment in obesity prevention and to facilitate more timely improvements in the health of populations. Under-resourced evaluations of community-based interventions offer little quality evidence to inform public health policy and practice. Selective investment in critical-mass funding of large, rigorously evaluated community-based interventions may represent a more efficient strategy to yield robust evidence of intervention effects( Reference Hennekens and DeMets 83 ). Funding comprehensive evaluations of targeted community-based obesity prevention interventions should therefore represent a priority for governments and other health-promoting funding agencies.

While the review provides useful guidance for the conduct of community-based obesity prevention intervention evaluations, there are a number of opportunities for further methods development to advance the field, particularly for initiatives utilising community-based participatory approaches. Community-based participatory research emphasises reciprocal transfer of expertise between community and researchers, sharing of decision making power and mutual ownership of the research process and products, and is increasingly being used to address a variety of public health issues in the community( Reference Viswanathan, Ammerman and Eng 49 , Reference Cargo and Mercer 84 ). While such approaches can facilitate conceptualisation of the problem and culturally appropriate intervention development and delivery, and improve data collection, analysis and interpretation( Reference Cargo and Mercer 84 ), participatory approaches introduce a number of unique challenges for evaluators. For example, evolving study procedures and processes may preclude the development of study protocols a priori and increasing the specificity of research to a community can reduce the generalisability of the research outcomes( Reference Cargo and Mercer 84 ). While broad guidelines exist to assist with the conduct of quality participatory research( Reference Green, George and Daniel 85 ), further development of measures to assess participatory processes and constructs and more sophisticated analytical techniques to deal with such complexity are required( Reference Sandoval, Lucero and Oetzel 86 ).

Greater examination of factors which may mediate or moderate an intervention effect may also present an opportunity to further an understanding of the casual pathways in which interventions operate and to identify particular groups in the community for which an intervention may be beneficial( Reference MacKinnon and Luecken 87 , Reference Cerin and Mackinnon 88 ). Despite the benefits of such research, few trials have examined such relationships in obesity prevention research generally( Reference Cerin, Barnett and Baranowski 89 ). Encouragingly, within community-based obesity prevention research Johnson and colleagues recently published a multilevel analysis of the Be Active Eat Well initiative, in which a moderating effect of the intervention was found for the relationship between the frequency of watching television during meals and BMI( Reference Johnson, Kremer and Swinburn 90 ). A greater understanding of such relationships will aid future efforts to design and evaluate community-based obesity prevention initiatives.

For complex community-based interventions, the conduct of rigorous evaluations undoubtedly represents a considerable challenge. Evaluators need to carefully examine and the strengths and pitfalls of decisions regarding evaluation design, data collection, measurement and analysis, and seek to maximise evaluation rigour in the context of political, resource and practical constraints. The present paper attempts to provide guidance for evaluators to do so.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The review was conducted with the infrastructure support provided by the Hunter Medical Research Institute and salary support provided to L.W. through the NSW Cancer Institute. Authors’ contributions: L.W. conceived the manuscript idea and led the drafting. J.W. provided critical comment on drafts. Both authors reviewed and approved of the final version of the manuscript. Conflicts of interest: Both authors are currently involved in the evaluation of a community-based obesity prevention intervention. Both have no conflicts of interest to declare. Ethics: Ethical approval was not required. Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Jenna Hollis who assisted with data extraction.

Search strategy: MEDLINE

1. obesity.mp.

2. prevention.mp.

3. 1 and 2

4. nation$.mp.

5. state.mp.

6. count$.mp.

7. district.mp.

8. regio$.mp.

9. communit$.mp.

10. area.mp.

11. town.mp.

12. village.mp.

13. borough.mp.

14. municip$.mp.

15. province.mp.

16. shire.mp.

17. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

18. randomized controlled trial.pt.

19. controlled clinical trial.pt.

20. randomized.ab.

21. randomised.ab.

22. clinical trials as topic.sh.

23. randomly.ab.

24. trial.ti.

25. double blind.ab.

26. single blind.ab.

27. (pretest or pre test).mp.

28. (posttest or post test).mp.

29. (pre post or prepost).mp.

30. Before after.mp.

31. (Quasi-randomised or quasi-randomized or quasi-randomized or quazi-randomised).mp.

32. stepped wedge.mp.

33. Preference trial.mp.

34. Comprehensive cohort.mp.

35. Natural experiment.mp.

36. (Quasi experiment or quazi experiments).mp.

37. (Randomised encouragement trial or randomized encouragement trial).mp.

38. (Staggered enrolment trial or staggered enrollment trial).mp.

39. (Nonrandomised ornon randomised or nonrandomized or non randomized).mp.

40. Interrupted time series.mp.

41. (Time series and trial).mp.

42. Multiple baseline.mp.

43. Regression discontinuity.mp.

44. 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43

45. 3 and 17 and 44

46. 45

47. limit 45 to year = ‘1991-201’