Introduction

In 1999, the Tampere European Council declared that the development of international partnerships was to be one of the main political activities necessary to better manage the migration and asylum policy (MAP) in the European Union (EU). Since then, cooperation with migrants' origin and transit countries has become one of the leading political objectives of the MAP. The EU has thus developed a wide range of legal and political measures aimed at implementing international cooperation in this specific field, involving transit and origin countries in the EU's management of migration and asylum. This process is known as the ‘external dimension’ of the European MAP (Longo, Reference Longo and Bindi2022) and has so far been analyzed to understand EU migration governance (Huysmans, Reference Huysmans2000; Lazaridis and Wadia, Reference Lazaridis and Wadia2015; Moreno-Lax, Reference Moreno-Lax2018), or to explore the practices of external migration management in Europe (Bello, Reference Bello2022; Fontana, Reference Fontana2022; Leonard and Kaunert, Reference Leonard and Kaunert2022; Panebianco, Reference Panebianco2022a). Most of this literature has stressed that the ‘external dimension’ is mainly guided by the EU's will to shift responsibilities for migrants and refugees toward transit and/or origin countries and, sometimes, this involves agreements which do not comply with international and European standards of human rights. This paper contributes, instead, to existing literature on the external dimension of the European MAP by assessing the gap between the EU's rhetoric and its practices, that may be regarded as a case of organized hypocrisy (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989; Krasner, Reference Krasner1999). Brunsson conceives of the ‘organization of hypocrisy’ as inconsistencies among the talk, decisions, and actions which complex organizations adopt for handling and acting out inconsistent values and norms in their environment (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989). We argue that the EU acts with ‘organized hypocrisy’ when cooperating on migration and asylum issues with Southern neighbor countries (SNCs), as defined within the framework of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), which is the main institutional architecture for Euro–Mediterranean relations since the early 2000s.

Cooperation with ENP countries represents a critical case for discussing organized hypocrisy. As the ideal continuation of the Euro–Mediterranean Partnership launched in 1995, the ENP constitutes a region-wide normative framework on the ground of which MAP cooperation has been developed. This results in a fundamental tension between the regional dimension of EU talk, in terms of values and rationale for MAP cooperation, and the bilateral dimension of EU actions toward SNCs, which reflects a greater differentiation. Moreover, ENP-based cooperation implies a further friction when it comes to MAP. Given their role in ‘gatekeeping’ migration flows, cooperation with SNCs is essential in order to control EU borders and, at the same time, is rhetorically constructed as the locus of European humanitarian commitment.

The EU, like other organizations, finds it easier to talk than to act (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989) and responds to conflicting pressures in external environments through contradictory actions and statements (Lipson, Reference Lipson2007). This hypocrisy allows the EU's survival. The EU cannot promote consistent norms because of conflicting preferences, since the strategic interests of individual member states often undermine the values they advocate. The external dimension of the European MAP is the result of the interaction between the EU and its member states, often faced with conflicting domestic pressures that might be managed by decoupled responses – at the EU level – to contradictory external stimuli and constraints. EU institutions, on their hand, are keen to present a humanitarian discourse. Our research shows that the EU cannot shape the external dimension of the European MAP via those principles and norms that it consistently claims as being essential, to be pursued both domestically and internationally. Instead of shaping the external world via principle and norm-based cooperation and international partnerships, the EU is constrained by domestic challenges. As with other organizations, what the EU says often diverges from what actually does (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989). Despite humanitarian discourses on migration and asylum, particularly those of the European Commission, EU cooperation with origin and transit countries does not translate into value-based action. The EU lacks the instruments to overcome the contradictions inherent in the EU member states' (EUMS) different normative expectations (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989). Applying this ‘organized hypocrisy’ framework to the external dimension of the European MAP, the paper explores this tendency to decouple EU values and actions; moving beyond the consolidated debate on the EU's inconsistent normative stances in the external dimension of the European MAP, it provides an explanation of what prevents the EU from respecting international norms.

This research provides an additional explanation for the complex institutional architecture of migration governance and addresses a series of questions. Are the EU's humanitarian pronouncements consistent with its policy actions? Is EU cooperation with SNCs relevant to guaranteeing the mobility rights of migrants within and across the Mediterranean area, as the EU's rhetoric claims? Does the external dimension of the MAP contribute to the reinforcing of a legally based humanitarian approach that strengthens international protection or, conversely, does it act at its expense?

Our main hypothesis is that the external dimension of the European MAP affects the capability of the EU to comply with the international regime on international protection. The empirical research focuses on the impact on international protection of EU cooperation with SNCs. Drawing on original qualitative analysis, we explore the EU practices of transferring border control to third countries through formal and informal agreements. Recent research casts doubts on the extent to which the ethical concerns expressed in EU documents are translated into policy action. Indeed, when the declared commitment to the humanitarian approach conflicts with more pragmatic interests, we argue, the EU acts via ‘organized hypocrisy’, decoupling its talk and action.

The article is structured as follows. The next section explores the missing link between EU talk and action concerning the external dimension of the European MAP, in order to identify a useful analytical approach to its organized hypocrisy in cooperation with SNCs. Then the research design, case selection, adopted methods, and empirical data are explained. The subsequent session illustrates and discusses the empirical findings. Finally, in the conclusions, we reconnect our work to the existing research agenda on international protection and pave the way for further research.

Conceptual tools and analytical framework: the missing link between humanitarian talk and cooperation actions

A substantial body of literature has explored how organizations – UN, IMF, WB, NATO – decouple talks and actions, proving the inconsistency between rhetoric and actual behavior (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989; Lipson, Reference Lipson2007). There is ‘hypocrisy’ when ‘ideas and action do not directly support one another’ (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1989: 172). Originally drawn from organizational theory, the concept of ‘organized hypocrisy’ was introduced into International Relations by Krasner (Reference Krasner1999), to account for the violation of international legal sovereignty by states. The mismatch between rhetoric and action is traditionally considered a strategy of organizations for reconciling divergent interests among actors. The gap between EU talk and action is attracting increasing scholarly attention (Hansen and Marsh, Reference Hansen and Marsh2015; Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018; Cusumano, Reference Cusumano2019; Cusumano and Bures, Reference Cusumano and Bures2022). Yet, what still deserves to be assessed is why the EU acts as an organized hypocrisy, namely which are the external/internal constraints that prevent the EU from adhering to its norms and values. This analysis of the external dimension of the European MAP contributes to the existing debate on the EU as a case of ‘organized hypocrisy’, and explains why there is a mismatch in the specific area of international cooperation on migration and asylum ‘between the EU's normative striving towards a “union of values” and the political and institutional limits imposed’ (Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018: 1195).

This research adds empirical substance to the debate dealing with the EU as a case of organized hypocrisy drawing from cooperation with SNCs. To map the mismatch between talk, decisions, and action, we conduct content analysis of EU–SNCs agreements, declarations, and action plans via a frame analysis. Qualitative analysis of the external dimension provides an example of a ‘minimum common denominator’ policy, that results from different voices, priorities, and interests expressed by EUMS and EU institutions. The frame analysis relies on three policy frames, identified in EU documents, that we call ‘protection through interdiction’, ‘addressing the root causes’, and ‘human security’ frame (see infra). These frames are anchored to conceptual tools that need to be clarified before analyzing the EU as a case of organized hypocrisy, namely those of humanitarian approach, human security, externalization, and the external dimension of the MAP.

Recent research has emphasized the central role of humanitarian concerns in the EU discourse about external action, as it was the case of the human and humane approach to manage migration depicted in the Pact on Migration and Asylum, launched by the European Commission in 2020 (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco2021). A humanitarian approach with a migrant-centered focus is shared by non-state actors engaged with migration management in the EU periphery (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco2022b), while it is difficult to implement at a macro, EU level. Our conceptualization of the EU's humanitarian approach draws on the critical security studies' definition of human security, that puts human beings at the center of the analysis (Kaldor et al., Reference Kaldor, Martin and Selchow2007) and identifies individuals as the referent objects of security (Kerr, Reference Kerr, Dunn Cavelty and Mauer2010). However, humanitarian concerns do not translate into effective policy-tools for the implementation of human security, particularly when migrants' security is outsourced to EU partner countries, accused of human rights breaches.

The EU's failure to develop common policies (Boswell, Reference Boswell2003), combined with the increased migratory flows across the Mediterranean Sea, encouraged an increasing involvement of non-EU countries in the management of migration (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco2022a). In 2015, the European Commission adopted the European Agenda on Migration, listing various proposals for reforming, extending, and better implementing the Schengen regulatory framework (FWK9, in the Appendix). This Agenda was motivated by the principles of solidarity and ‘fair sharing of responsibility’ which are expressed in the EU treaties. However, this approach was soon questioned and partially abandoned. The European response to the Mediterranean migration crisis in the mid-2010s revealed contradictory strategies, failing the ‘burden-sharing test’. The leaders of the so-called Visegrad countries contested the refugee quota system that established an automatic redistribution mechanism. European states and policy-makers turned to pursuing a bold return policy, investing in externalization.

By relying on intermediaries, the EU requires fewer resource commitments, yet direct engagement of third countries often has consequences in terms of legal liability. This can raise humanitarian concerns and lead to the creation of a ‘vacuum of legal protection’ (Fontana, Reference Fontana2022) regarding migrants and asylum seekers, who will not have the opportunity to legally access a safe territory. This mismatch between rhetoric and action is depicted by the term ‘organized hypocrisy’. The EU acts with organized hypocrisy to cope with contradictory institutional goals, and manage different and opposing preferences of relevant political actors, to circumvent EU standards through externalization (Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018). Lavenex has applied this concept to asylum and migration issues and analyzed the crisis of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) during the so-called refugee crisis of the mid-2010s and the reaction of the EU, which has led to the continuous ‘de-coupling between protective aspirations and protectionist policies, since 2015’ (Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018: 1196). The gap between the EU missions' humanitarian rhetoric and the operational handling, primarily centered on limiting irregular migration, has also been observed in the EU maritime missions (Cusumano, Reference Cusumano2019).

In the organized hypocrisy perspective, differences between ‘talk and behavior’ are considered the results of the EU's strategy for balancing the contradictory expectations arising from the coexistence of incompatible norms and interests. This is the case for EU ‘agencies tasked with conducting EU external policies, which suffer from the uneasy coexistence of the normative commitment to be a “force for good in the world” and the diverse material interests of its member states’ (Cusumano, Reference Cusumano2019: 4).

Here, we apply the concept of organized hypocrisy to the external dimension of the European MAP to identify and explain a growing mismatch between the EU's engagement to protect asylum seekers and policies for managing migration. In fact, existing agreements with SNCs make access to European borders increasingly difficult, having a strong impact on the right to apply for international protection. Barriers to entry, procedural restrictions to asylum-seekers, interception, and return of irregular migrants challenge the right to asylum and international protection, and establish a structural bias in the protection policy of the EU. At the same time, the facilitation of mobility, which the EU offers as compensation for enhanced control and security cooperation, tends to be restricted to narrow categories of highly skilled migrants, and resettlement is seldom part of the deal. In most cases, this is mentioned in terms of a vague commitment rather than as a programmatic objective.

The development of the European MAP, as it was envisaged in the EU system since the 1970s (Guiraudon, Reference Guiraudon2003), demonstrates that, despite the EU's attempts to adopt humanitarian policy instruments, it remains a selective migration controller (Panebianco and Carammia, Reference Panebianco, Carammia, Chueca, Gutiérrez and Blázquez2009). Since the 1970s, migration and asylum issues have been discussed at a common level. However, MAP formally entered the EU policy agenda only in 1993, with the Treaty of Maastricht. Since 1999, the EU has developed a multifaceted policy for involving migrants' countries of origin and transit in the control of migration flows. This includes several political, legal, and financial instruments designed to enhance cooperation with third countries in the management of migration, borders, and asylum. Scholars have defined this as the ‘external dimension’ of the EU's common MAP (Boswell, Reference Boswell2003; Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2006; Reslow, Reference Reslow2012; Longo, Reference Longo and Bindi2022) and it has been seen as the incorporation of EU migration and asylum policies within the scope of the EU's policy on external relations.

The ‘external dimension’ of the European MAP can be regarded as the result of adding migration and asylum issues to the EU's security agenda, and is part of a larger process of re-definition of the EU security concept, based on the indivisibility of the domestic and external aspects of security (Longo, Reference Longo2013). The process of inclusion of migration in the security agenda has had two main effects. The first is the connection of migration policy with the European border regime (Hesse and Kasparek, Reference Hesse and Kasparek2017), with a strong emphasis on border checks and control as main instruments for managing migration. The second is the development of a dual-track approach that aims to separate migration and asylum. Although migration and asylum share a legal basis and are part of the larger political domain of the area of freedom, security, and justice, they do not share the same policy approach (Longo, Reference Longo and Bindi2022). Migration policy is generally framed within the security approach, while asylum policy tends to be framed as part of the human rights approach, which derives from the need to comply with international standards on protection of asylum seekers. The external dimension of the European MAP includes different policy strands, characterized by different policy frameworks, which collide and produce opposite and inconsistent policy outputs. Most recent developments in the EU's external migration policies indicate that the EU focuses on policy instruments such as returns, readmission agreements, mobility partnerships, etc., identified as ‘strategic tools’ (Longo and Fontana, Reference Longo and Fontana2022: 493) for border control.

Externalization, which may be seen as the burden-shifting of EU border-control to third countries, weakens international protection. Existing policy instruments of external migration and asylum governance such as returns compromise international protection. Assuming that externalization is a process of outsourcing the EU's external border management to neighboring countries (Del Sarto, Reference Del Sarto, Bechev and Nicolaïdis2010; Bialasiewicz, Reference Bialasiewicz2012; Zaiotti, Reference Zaiotti and Zaiotti2016; Spijkerboer, Reference Spijkerboer2018; Moreno-Lax and Lemberg-Pedersen, Reference Moreno-Lax and Lemberg-Pedersen2019; FitzGerald, Reference FitzGerald2020; Müller and Slominski, Reference Müller and Slominski2021), EU relations with Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon are here compared to assess the extent to which the EU is delegating to neighboring countries the management of irregular flows. Indeed, despite the absence of explicit ‘burden-shifting’, as in the emblematic case of the EU–Turkey Deal, the emphasis on strengthening SNCs' legal frameworks for international protection and their reception capacity appears to respond more to the functional logic of preventing departures than to human security concerns.

In the EU's founding treaties, in political discourses and legal agreements with third countries, the EU identifies human security as a major objective of foreign policy. However, the empirical analysis reveals that this goal is challenged by policy instruments aiming at border closure and control. A comparison is here conducted to test the hypothesis that, despite humanitarian discourses, particularly those of the European Commission, the EU has reacted to the migration crises of the last decade with a growing externalization of migration management to third countries at the EU borders, and SNCs are no exception. The EU is systematically investing in a burden-shifting process of EU border control that relies upon Euro–Mediterranean association agreements (AAs), action plans (APs), mobility partnerships (MPs), etc.

In this perspective, the analysis of agreements, dialogues, and other instruments for bilateral and multilateral cooperation between the EU and the five selected SNCs provides an empirical test for verifying the main hypothesis that defines the external dimension of the European MAP as a form of ‘organized hypocrisy’, understood as a systemic gap between the EU's ambition to act as a normative actor able to provide an appropriate standard of international protection and the political practices for securing borders.

Research design: case-selection, methods, and data

In order to give substance to our claim that a gap exists between talk and action in the external dimension of MAP, this research explores the compatibility between MAP instruments and international protection. As a case-study, it investigates EU cooperation on migration and asylum with SNCs in the time span 1995–2020. Despite humanitarian discourses, particularly those of the European Commission, the EU has reacted to the migration crises of the last few decades strengthening the external dimension of the European MAP, getting a closer involvement of neighboring countries in migration management. The empirical research seeks to intercept policy changes that have characterized the external dimension in these 25 years.

Five SNCs have been selected, namely Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, to determine whether the policy instruments set up by the EU are consistent with its claimed ‘humanitarian approach’ in the Southern neighborhood. Such a choice is based on two main criteria. A material one derives from the existence of cooperation agreements concerning MAP. A theoretical one relies on the absence of intervening variables, such as prolonged conflicts in partner countries or sui generis political dynamics, that might affect the coherence between EU talk and actions. For these reasons, we have excluded some SNCs such as Syria, Libya, and Palestine, which underwent major turmoil in the selected period resulting in ‘contested statehood’ (Papadimitriou and Petrov, Reference Papadimitriou and Petrov2012), a condition that prevented the establishment of long-term forms of cooperation. In particular, while Libya came to play a critical role in the externalization of EU migration policies, such cooperation has been developed through yearly ‘Special Measures’, outside the institutional framework that governs Euro–Mediterranean relations. Hence, the peculiar character of EU–Libya relations makes this case different from other SNCs when it comes to discuss cooperation patterns on MAP.

A different set of reasons motivate the exclusion of Israel and Algeria from the sample as a consequence of their ‘exceptionalism’. Due to Israel's status as a formal, fully fledged democratic state, and the fact that it is not along the major migration routes to Europe, migration and asylum have been rather marginal in EU–Israel cooperation, compared to other SNCs (Schumacher and Bouris, Reference Schumacher, Bouris, Bouris and Schumacher2017). Algeria, by contrast, was among the last SNCs to conclude a Euro–Mediterranean AA, which entered into force in 2005, and has long refused tighter cooperation under the ENP. In 2017, the adoption of shared Partnership Priorities established an operational framework for cooperation, yet even then Algiers was rather reluctant to engage in dialogue on migration and asylum, preferring to continue its long-term pattern of (non-)cooperation (Zardo and Loschi, Reference Zardo and Loschi2022).

Focusing on the Southern neighborhood, we had to leave out also Turkey, a country that plays a pivotal role in the external dimension of the European MAP. Having the official status of candidate country, Turkey is eligible for EU financial support through the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance and is not included in the ENP framework. Limiting the case selection to these five SNCs that have long-lasting relations with the EU, allows us to demonstrate that the ENP is a long-term institutional cooperation framework that does not guarantee international protection.

Against this background, the research develops a qualitative analysis of selected documents and agreements addressing migration and asylum issues,Footnote 1 at least partially. Collected data include a number of external dimension policy instruments, which allowed us to identify and operationalize ‘humanitarian policy instruments’. Following the methodology adopted by Longo and Fontana (Reference Longo and Fontana2022), the empirical research has collected and analyzed data on the number and characteristics of external dimension policy instruments according to the following variables: legal framework; type of instrument; specific purpose/subject; and geographical projection (Table 1). The document analysis has identified how policy instruments have changed in the selected period of time (1995–2020), paying specific attention to the Arab uprisings, in 2011, and the so-called migration crisis in the mid-2010s. Qualitative analysis of the external dimension's policy instruments has been conducted, to classify data in different categories organized around the following variables:

(a) assessment of the political and legal patterns of cooperation between the EU and SNCs in the field of migration and asylum;

(b) role(s) and relevance of third countries in Mediterranean migration governance;

(c) evaluation of the impact of the external dimension on the capability of the EU to comply with regional and international regimes of asylum and protection.

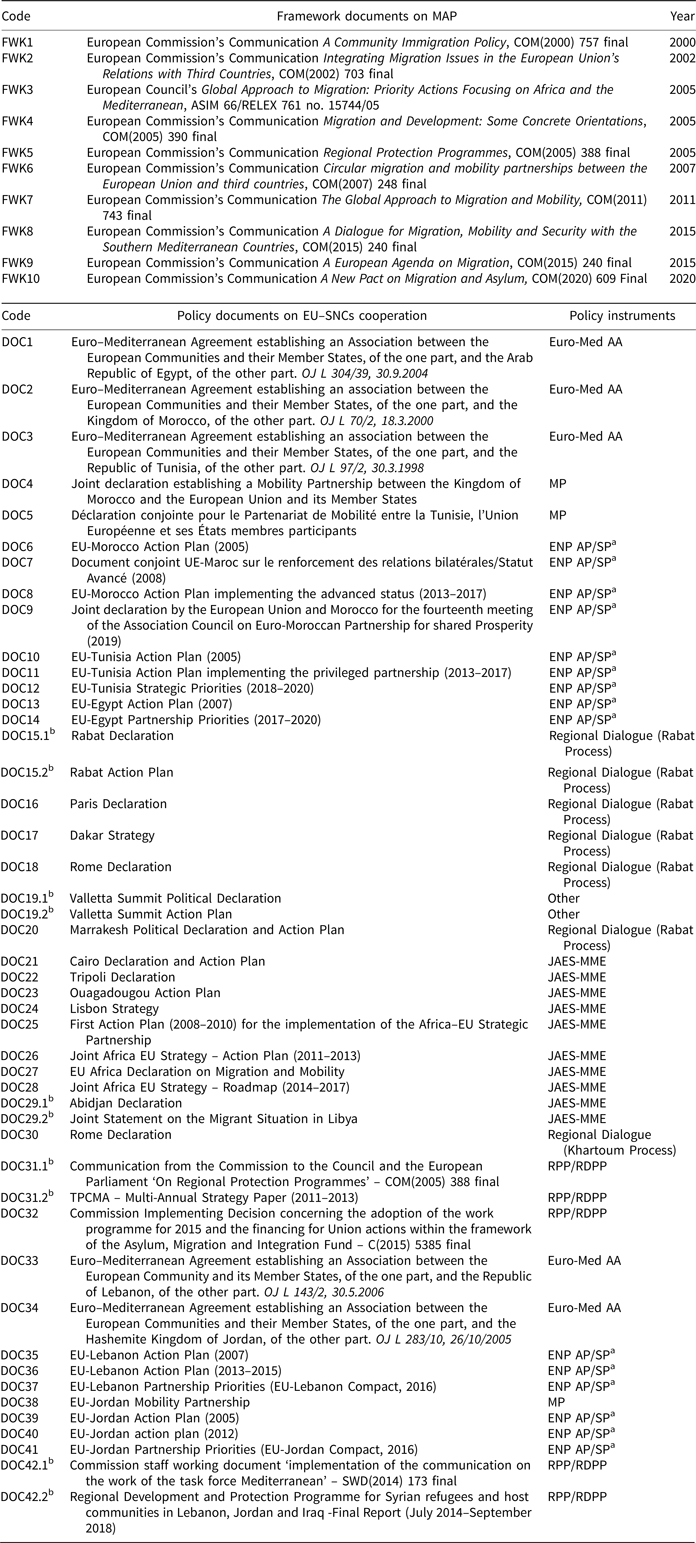

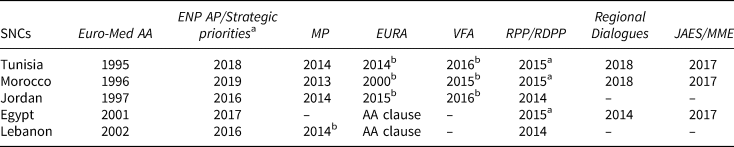

Table 1. Agreements, dialogues, and frameworks for the MAP external dimension (1995–2020)

a The years listed in the table refer to the last revision or update of the agreements and tools between the EU and the concerned partner. In the ENP framework, the reference is to the most recent AP or documents on partnership/strategic priorities. As for RPP/RDPP, the year 2015 refers to the launch of the new RDPP – North Africa, which replaced the RPP – North Africa, already in place since 2011.

b Negotiations concerning these agreements and tools started in the mentioned year but have not been concluded yet. As far as Lebanon is concerned, while the MP is currently under negotiation, a Dialogue on Migration, Mobility, and Security was launched in December 2014.

Table 1 offers an overview of the most relevant agreements, dialogues, and frameworks concerning EU cooperation with Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, from 1995 to 2020. The overarching framework is that of Euro–Mediterranean AAs, on the basis of which the different APs and strategic priorities have been agreed. These bilateral political agreements were formally adopted by the Association Councils set up through AAs. While these institutions are intergovernmental, it is the European Commission that plays a pivotal role concerning both the drafting process and the negotiation of the APs (Börzel and van Hüllen, Reference Börzel and van Hüllen2014; Gastinger and Dür, Reference Gastinger and Dür2021).

Other crucial bilateral agreements which constitute the external dimension of the European MAP are the MPs, introduced in 2007 as framework agreements to step up cooperation on legal migration opportunities in return for SNCs' action ‘against illegal migration and facilitating reintegration of returnees, including efforts to provide returnees with employment opportunities’ (FWK6 in the Appendix). In the context of MPs, the negotiation started in parallel on both EU readmission agreements (EURAs) and visa facilitation agreements (VFAs), intended as counterbalances in a ‘more for more’ approach (FWK7 in the Appendix).

On the multilateral level, migration cooperation has been central both in the continental Dialogue on Migration, Mobility, and Employment (MME), based on the Joint Africa–Europe Strategy (JAES), and in the two regional dialogues, the so-called Rabat Process and Khartoum Process. More than providing a legal tool for international cooperation, all multilateral frameworks offer a forum for political dialogue between EU and partner countries, to define the priorities for bilateral cooperation and agree on new tools, as was the case for the European Union Trust Fund for Africa. More recently, the EU launched two Regional Development and Protection Programmes (RDPPs) devoted to the North African and Middle Eastern areas, respectively in 2011 and 2015. Such multilateral programs, built on the concept of the Regional Protection Programmes (RPPs), originally launched in 2005, aim to ‘enhance protection capacity, better access to registration and local integration and assistance for improving the local infrastructure and migration management’ (FWK5 in the Appendix).

Building on our theoretical framework, we argue that the EU decouples its rhetoric about MAP from its practices of cooperation with SNCs. In other words, we aim to demonstrate that the EU makes use of organized hypocrisy to manage competing demands for controlling its external borders and reducing the burden of processing refugee applications, on the one hand, and to live up to its normative commitment to international protection and human rights, on the other. To test such hypotheses, we draw on frame analysis (Rein and Schön, Reference Rein and Schön1996) as an instrument to interpret EU rhetoric talk embedded in its political declarations and agreements, which constitute the normative foundation of the external dimension of MAP, in order to weigh such talk against the actions and measures proposed. In Rein and Schön's work, frames are defined as ‘strong and generic narratives that guide both analysis and action in practical situations’ or even ‘diagnostic/prescriptive stories that tell, within a given issue terrain, what needs fixing and how it might be fixed’ (Rein and Schön, Reference Rein and Schön1996: 89). Such causal narratives, we assume, have a ‘constitutive effect’ on the external dimension of the European MAP, inasmuch as these latter contribute to the definition of ‘policy problems’ and ‘solutions’, thus grounding and legitimizing certain courses of actions and excluding others.

Our coding process was carried out, in the first place, on a sample of framework documents (the FWKs listed in the Appendix), according to a theory-driven deductive approach based on relevant existing literature (van Gorp, Reference Van Gorp2005; Dekker and Scholten, Reference Dekker and Scholten2017; Greussing and Boomgaarden, Reference Greussing and Boomgaarden2017). Such a first round of coding aimed at distinguishing elements and categories referring to two broad frames, a ‘humanitarian’ and a ‘security’ one. Given that, in some circumstances, the meaning of such broad categories might be blurred, we adopted a clear-cut distinction. In order to conduct our analysis, we needed to detect the ‘humanitarian approach’ in the practice of EU migration governance, and explain the consequences of existing decoupling stances in terms of international protection. Following Barnett, we defined humanitarianism as a commitment to ‘relieve suffering, stop preventable harm, save lives at risk, and improve the welfare of vulnerable populations’ (Barnett, Reference Barnett2013: 382), thus including aspects relating to human security as part of this first frame. We conceived, instead, of security in terms of ‘national security’, hence referring to concepts such as controlling borders, preventing irregular immigration, and halting migration flows.

After this first round of coding, we engaged in more inductive, data-driven coding of the actual policy documents underlying EU–SNCs cooperation on MAP, which resulted in the identification of three frames. These frames were identified following the coding of what van Gorp (Reference Van Gorp, D'Angelo and Kuypers2010) defines as ‘framing devices’ – that is, specific metaphors or lexical choices functioning as indicators of a certain frame. Then, drawing on Boswell et al. (Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011), we interpreted clusters of framing devices and reasoning devices – that is, explicit or latent textual propositions defining a ‘route of causal reasoning’ (van Gorp, Reference Van Gorp, D'Angelo and Kuypers2010: 91) – to operationalize frames as composed of three core elements: (a) descriptive claims, about the definition and nature of the problem – that is, ‘naming’ the issue at stake; (b) diagnostic claims, which identify specific factors and actors to hold responsible for the existence of a certain problem; and (c) prognostic claims, referring to claims about possible solutions to policy problems – that is, about policy interventions and their expected effects. Our main objective was to reconstruct the actual operationalization of EU talk in the agreements implementing the external dimension of MAP and to assess their coherence with the normative discourse emerging from framework documents, in the light of the organized hypocrisy argument. Hence, we looked at how the EU and SNCs defined ‘problems’ that MAP cooperation was meant to address (description) and the causal claims about their origins (diagnosis), so as to assess whether these narratives emerging from international agreements and other documents legitimize the choice of measures and interventions (prognosis) aiming to externalize not only border controls, but also international protection.

Empirical findings

Our results provide empirical evidence for the assumption that the EU enacts organized hypocrisy in cooperation with SNCs concerning migration and asylum issues revealing a gap between humanitarian talk and practices of border control. In other words, we argue that the policy instruments that the EU has agreed on with SNCs, while hinging on humanitarian discourses, fail to provide adequate means to strengthen international protection, focusing on – in parallel with the externalization of borders and border controls – some sort of ‘externalization of international protection’.

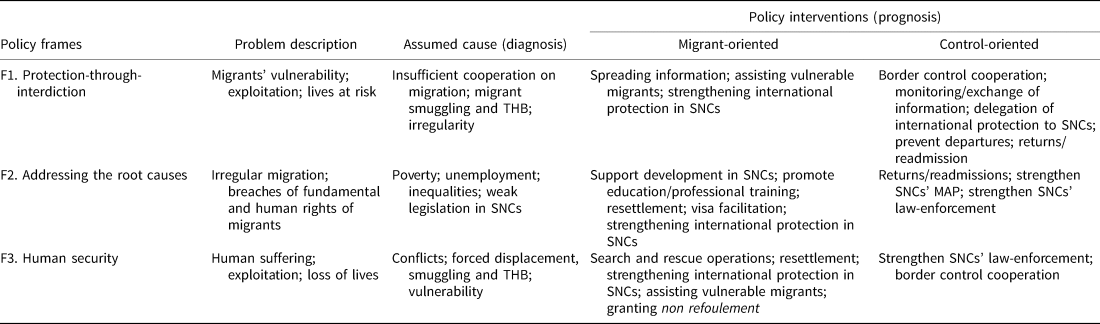

Our qualitative analysis identifies framing devices related to humanitarian and security frames that appear in the same segments of EU policy documents. Indeed, based on our coding of the framework documents listed in the Appendix, international protection – which relates to humanitarian framing, according to our definition – often occurs in conjunction with more security-oriented concepts, such as cooperation on returns and readmissions or irregular migration. While examining more humanitarian-oriented framing devices, such as the concept of migrants' vulnerability, we observed more occurrences with codes such as ‘combating organized crime’. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the relations between coded segments. When analyzing EU talk, as it emerged from framework documents dealing with external dimension agreements and instruments, we found that the EU's humanitarian discourses tend to be disavowed in the practice of MAP cooperation. Hence, we identified three main frames connecting humanitarian talk to de facto security-oriented measures of cooperation, which make our case for organized hypocrisy.

Figure 1. Visual map of EU talk based on framework documents concerning the external dimension of the European MAP.

Table 2 offers a global picture of the three main frames we identified via qualitative analysis and of the interventions proposed to address migration and international protection. We labeled a first frame ‘protection-through-interdiction’ (F1), since it identifies migrants' lives at risk as the main problem, hence building on a sort of humanitarian narrative, but points at irregular movements and insufficient cooperation as the main causes of such risks. Albeit adopting a humanitarian frame, the EU tends to delegate to transit countries relevant aspects of border management, asylum procedures, and protection of vulnerable migrants and refugees, regardless of national problematic track of records in terms of international protection standards. A somewhat similar combination of concerns characterizes the ‘addressing the root causes’ frame (F2). According to such an interpretation, the EU identifies migration as an epiphenomenon of poverty, unemployment, and inequalities in countries of origin, so that human security of migrants and refugees is better addressed through the promotion of development and legislative reforms in partner countries: the need for international protection seems to be considered as a consequence of lack of cooperation on development, rather than a problem in itself. Such an idea of ‘preventing migration by addressing its root causes’ (Zaun and Nantermoz, Reference Zaun and Nantermoz2022) was present in particular within multilateral cooperation instruments, such as the regional and continental dialogues on migration and mobility, but also in RDPP which, since 2014, has incorporated a ‘development component’ along with the ‘protection’ one. The third, more migrant-centered frame, defined as a ‘human security’ frame (F3), assumes migrants' insecurities and suffering as the main (and contingent) focus of EU cooperation with SNCs. Such a frame concerns, for instance, support and assistance to victims of migrant smuggling and trafficking in human beings (THB). Here, the EU acknowledges external causes such as conflicts and forced displacement as the source of migrants' insecurities, so that the interventions foreseen are more consistent with humanitarian discourse. Despite the different nuances, the three frames hinge on some sort of humanitarian discourse. However, as Table 2 shows, such humanitarian framing clashes with the actual measures proposed to address the problems, which tend to be aligned with a control-oriented approach.Footnote 2

Table 2. Framing irregular migration and international protection in the external dimension of the European map

We acknowledge that to consider the selected documents as reflecting EU talk might be problematic. As a multi-level organization in which different institutional and non-institutional actors interact, reducing the EU's discourse to what emerges from international agreements, thus excluding other forms of outward communication (e.g. press releases or internal institutional communication), might limit the relevance of our results. However, the examined documents are not just legal texts, but rather entail a proper public dimension; most of them are political declarations which had a considerable resonance in European political debates. In this regard, Reslow and Vink (Reference Reslow and Vink2015) argue that EU external policies can be understood as a three-level game unfolding at the same time within the EUMS' domestic political arenas, at the level of EU supranational bargaining, and of international negotiations with third countries. Different demands emerge from these levels, which the EU endeavors to ‘manage’ through organized hypocrisy. Our effort to understand which frames underlie EU cooperation on MAP and, specifically, on international protection, aims to disentangle the EU's responses to contrasting demands for these different levels. The empirical research seems to support the idea that the dynamics of international protection can be interpreted as the product of intertwined situations arising from global, EU, and domestic politics.

Indeed, while the EU's normative commitment to humanitarian values and international protection has been somehow stable throughout the last two decades, the strategies and interventions that the EU has adopted to address such commitment have been changing in order to respond to competing demands. In general terms, we can distinguish three major phases of EU–SNCs cooperation on MAP. In the first phase, from its inception in 2004 to 2010, EU efforts aimed to put into practice the cooperation envisaged in Euro–Mediterranean AAs, in the framework of the ENP. The second phase includes APs signed after the first ENP revision and the launch of the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility in 2011. The third relates to a further revision of the ENP, in 2015, taking stock of the consequences of the migration and refugee crisis, until 2020.

When ENP-based cooperation is established, the EU's focus, in terms of talk, is on border controls and prevention of ‘illegal’ immigration, while actions concerning international protection are limited to the exchange of information among the concerned EU and SNCs authorities (DOC13, DOC35 in the Appendix), in a logic of preventing emigration – and its risks for migrants' lives – and reinforcing SNCs' management capacities (DOC6; DOC10). The Arab uprisings in 2011 further exacerbated the tension between the aspiration of the EU as a norm promoter and its contingent concern to secure its borders. On the one hand, the strategic priorities negotiated in this period point at reinforcing cooperation to address the root causes of regional instability, while on the other, MPs stress the need of a ‘more for more’ approach, trading visa facilitation for cooperation on returns and readmission. Such efforts to strengthen the capacities of the SNCs' authorities to ‘manage migration’, promote a subtle delegation of international protection procedures, which also permeates regional programs (RPPs/RDPPs) launched in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings. It is significant, in this regard, that the final report for the first stage of the ‘RDPP – Middle East’ (2014–2018), while praising the achievement of improvements on most targets,Footnote 3 acknowledges that ‘it has not been possible to fully achieve the overall objective of the program, as the protection space in some ways has reduced’ (DOC42.2).

Such a trend was further reinforced in conjunction with the migration and refugee crisis, in 2015. Confronted with increasing arrivals and an unprecedented number of fatal shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea, the EU further pushed the gap between its rhetoric and actions. On the one hand, responding to calls from public opinion, it engaged in search and rescue operations in a human security logic. Yet, while in a first phase the imperative of ‘saving lives’ seems to guide EU actions, the agreements and partnership priorities signed after 2015 promote a de facto externalization of international protection, focusing on the need to prevent departures, either by addressing the root causes or through delegation, in the logic of a ‘protection-through-interdiction’ framing. For instance, the Compacts agreed with Lebanon and Jordan in 2016, as a response to the Syrian refugee crisis, prioritize the provision of technical and financial support to the two SNCs, including relaxation of market access for their goods, in exchange for their commitment to provide durable solutions for refugees. As for partnership priorities, we observed a new focus on the aspect of prevention as well as on reinforcing SNCs' legislative frameworks and capacities for coping with migration and asylum issues. Our results, hence, provide substance to some sort of incremental ‘externalizing approach’, which characterizes the EU's cooperation with SNCs on international protection, reducing in practice the guarantees for asylum seekers and preventing them from seeking refuge in Europe. Indeed, humanitarian discourses are not a guarantee per se that a migrant-centered approach is being adopted. The decoupling of EU talk and cooperation practices allows the EU to prioritize the protection of external borders, discouraging and, in some cases, de facto preventing asylum seekers from leaving, regardless of the difficult conditions they experience and transit countries' precarious reception capacities. Through adopting a ‘burden-shifting’ strategy, the EU acts in open contradiction with its own normative commitments to a ‘human and humane approach’ (FWK10), which is instead used as a ‘legitimizing talk’ to sustain external border policies. Such policies ‘effectively subsume humanitarianism and the provisions of international law’ within a de facto non-humanitarian agenda, ‘that focuses on removing “incentives” for asylum seekers’ (Little and Vaughan-Williams, Reference Little and Vaughan-Williams2017: 541).

Conclusions

This article has addressed crucial questions on the linkage between EU talk and action in its cooperation with SNCs, assessing another case of organized hypocrisy. Since the right to international protection is ‘subject to all kinds of turbulences in international and national politics’ (Sicakkan, Reference Sicakkan2020: 11), this empirical research has explored EU cooperation on migration and asylum with SNCs as a source of these turbulences. From a theoretical point of view, it has further developed the concept of organized hypocrisy, as it has been established in International Relations, to explain EU politics and policies. The empirical analysis has provided a deeper understanding of the incoherence between the rhetoric of a humanitarian approach and the practices of border control, adding further evidence to substantiate the term organized hypocrisy in relation to the EU. The research has explored and evaluated the relevance and the effectiveness of international cooperation on securing safe reception conditions and solidarity-based responses for migrants and for those seeking international protection. Indeed, the practices of border control are seldom consistent with the humanitarian approach that the EU, the European Commission in particular, often claims to adopt. Conversely, the analysis of EU cooperation with SNCs confirms the results of previous studies arguing that the EU tends to manage the migration crisis via ‘EU borders’ control by proxy’ (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco2022a), compromising humanitarian stances, international law, and the implementation of international protection.

A clear gap between EU humanitarian discourses and its security practices, framed within the concept of organized hypocrisy, has emerged from the analysis of the agreements on migration and asylum between the EU and five SNCs, namely Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon. In that respect, the research results provide empirical data to fine-tune the concept of organized hypocrisy and enrich it with the ‘constitutive versus declaratory’ dimensions in defining the EU's role in protecting migrants and asylum seekers at the domestic and global levels. EU founding principles of liberty, democracy and respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and the rule of law, articles 2, 3, 6, 21 of TEU, article 205 of the TFEU, the EU Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2020–2024, formally commit the EU to protect human rights in its external relations. Moreover, in the last decade the EU, particularly the European Commission, included the dimension of the protection of human rights in its MAP, depicting a role for the EU as a humanitarian actor at the global level. Nevertheless, evidence provided in this article demonstrates that, in the field of external relations with third countries concerning migration and asylum governance, the EU does not comply with this commitment. Policy tools hardly give rise to humanitarian policy practices and, for that reason, the humanitarian approach has a mere declaratory effect.

The EU has traditionally tended to be a selective migration controller (Panebianco and Carammia, Reference Panebianco, Carammia, Chueca, Gutiérrez and Blázquez2009). Policy tools adopted within the framework of EU relations with SNCs have shifted as a pendulum between MPs – designed at the time of the Arab uprisings in early 2010s as a way to frame legal pathways of mobility and border control, to border control via returns and readmission agreements. In the most recent years, provisions for readmission and returns have featured the external dimension of the European MAP, including SNCs. When borders' control and international protection are ‘outsourced’, migrants' vulnerability is not necessarily effectively addressed by the EU system of protection (Ceccorulli, Reference Ceccorulli2022). The EU seems reluctant to reform existing legal frameworks. For the time being, revising existing platforms of international protection is not on the agenda, while ad hoc international platforms are emerging and a form of organized hypocrisy seems to prevail. Further research is needed to assess whether international protection can be guaranteed via MPs, whether effective governance mechanisms of refugee protection can be adopted within EU cooperation with Mediterranean border countries, whether different forms of international protection are in the pipeline. Cooperation with third actors has become a key priority of Mediterranean migration governance, but international solidarity, norms, values, and legal protection are put at risk by policy tools that let burden-shifting prevail.

The results of this empirical research indicate that organized hypocrisy affects the capability of the EU to comply with the international protection regime. At the EU level, there is a clear divergence between humanitarian talk and practices of border control concerning the external dimension of the European MAP. This decoupling between talk and practice affects the capacity of the EU to assure international protection. Through organized hypocrisy the EU is able to decouple its domestic-directed talk about international protection from the practice of its cooperation with SNCs. Preventing migrants to reach the EU shores, de facto their chances to apply for asylum in the EU are constrained. In such a way, the EU manages to reduce pressures on the CEAS without incurring in the economic and social costs of rejecting asylum seekers.

Funding

This article is part of ‘PROTECT The Right to International Protection: A Pendulum between Globalization and Nativization?’ (www.protect-project.eu), a research and innovation project which is funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Framework Programme and coordinated by the University of Bergen (Grant Agreement No. 870761).

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.9.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this paper has been presented at the 2022 ISA Annual Convention. The authors would like to thank the ISA panelists and the anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Author contribution

This paper illustrates the results of a joint research. However, Francesca Longo drafted the third and fifth sections; Stefania Panebianco drafted the first two sections; Giuseppe Cannata drafted the fourth section and contributed to data collection illustrated in the Appendix and in the supplementary material.

Appendix

Since one of the aims of this research was to grasp the gap between talk and action in the European MAP, our analysis was conducted on two samples of documents. Those defined here as ‘framework documents’ (FWKs) are European Commission's Communications or Council Conclusions that set out the general aims and programmatic lines of European MAP policies. These documents address a wider public and represent a standardized and coherent expression of EU talk. In a second phase, instead, we focused on ‘policy documents’ (DOCs). That is, those agreements, memoranda and action plans that define the specific actions and objectives of EU–SNCs cooperation on migration. As a result, the analysis of policy documents allows us to weigh the consistency between official talk and the foreseen actions that the EU has agreed with its partners in the field of MAP.