Adolescence is a time in life between childhood and adulthood from the age range of 10–19 years(1) and can be further categorised into ‘early adolescence’ (10–14 years) and ‘late adolescence’ (15–19 years)(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli2). The importance of a healthy diet during adolescence to aid in achieving optimal health is well established(Reference Wu, Zhuang and Li3) and the school-setting provides an opportunity to facilitate promoting healthful dietary behaviours among this age group(Reference ALjaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem4). To achieve this, there is a need to better understand what influences adolescents' dietary choices in school and what recommendations for improvement have been suggested to develop effective and sustainable school-based interventions. Exploring the impact of school-based nutrition interventions in promoting positive dietary change among adolescents is also an essential consideration for future intervention design to optimise their success.

This review provides an insight into the importance of targeting adolescents’ dietary behaviours and why the school-setting is an opportune environment to achieve this. This review also considers key factors which influence adolescents' dietary choices within the school-setting and explores the success of previously conducted school-based interventions, aiming to identify promising intervention components which could be utilised in future interventions to facilitate adolescents' selecting healthier options within this environment.

Why target adolescents' dietary behaviours?

Adolescence represents a period of significant rapid physical, psychological and social growth(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli2,Reference Hargreaves, Mates and Menon5) , and thus, optimal nutritional intakes are required during this critical life stage to support this development and facilitate adolescents achieving their full potential(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6,Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story7) . Good nutrition is widely recognised as essential for current(Reference Lytle and Kubik8) and future(Reference Neufeld, Andrade and Suleiman9) health, with evidence suggesting that dietary behaviours established during adolescence track into adulthood(Reference Lake, Mathers and Rugg-Gunn10,Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly11) . Poor dietary intakes during adolescence have been associated with an increased risk of short-term (immediate) health consequences, such as weight gain, reduced academic performance and poor bone mineralisation(Reference Lytle and Kubik8), and the development of risk factors for chronic diseases in later life(Reference Lytle and Kubik8). Despite the importance of optimal nutrition during adolescence and the dissemination of specific nutritional guidelines, this life stage is recognised as a nutritionally vulnerable time(Reference Spear12), with adolescents' dietary intakes remaining suboptimal and failing to meet current nutritional recommendations(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, French and Hannan13,Reference Rippin, Hutchinson and Jewell14) . During the transitional phase from childhood to adolescence, adolescents begin to develop their own sense of autonomy, becoming more independent in their dietary decisions and less reliant on their parents or guardians(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon15). This transitional period and increased autonomy can be associated with less favourable dietary behaviours(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon15,Reference Lytle, Seifert and Greenstein16) . Additionally, social determinants can influence this population's dietary behaviours, with those residing in areas of higher socio-economic deprivation reported to have poorer quality diets than those of higher socio-economic status(Reference Hanson and Chen17,Reference Utter, Denny and Crengle18) . Given that poor dietary habits established during adolescence can track into adulthood(Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly11) and become more resistant to change(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey19), promoting healthful dietary behaviours among adolescents, when these behaviours are still developing, is imperative to reduce the risk of future ill-health.

Moreover, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among the adolescent population is of increasing concern. Overweight and obesity during adolescence is associated with an increased risk of adverse health effects developing in adulthood, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke and CHD(Reference Reilly and Kelly20). Adolescent overweight or obesity can also predispose individuals to being overweight or obese in adulthood(Reference Singh, Mulder and Twisk21), leading to an increased economic burden on healthcare systems(Reference Withrow and Alter22). Whilst obesity rates are reported to be stabilising in children (<11 years)(Reference Van Jaarsveld and Gulliford23,Reference Blake and Patel24) , obesity rates among adolescents continue to rise globally(Reference ALjaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem4,Reference Van Jaarsveld and Gulliford23–Reference Fan and Zhang25) , further emphasising the importance of targeting health promotion strategies at adolescents. Although adolescence presents an opportune time to intervene and promote positive dietary behaviours to optimise current and future health, adolescents have previously been overlooked in nutrition policy globally(Reference Al-Jawaldeh, Bekele and de Silva26) and directing more attention towards this age group has been identified as a priority(Reference Dick and Ferguson27).

Why target the school-setting?

Adolescents spend a significant proportion of their time in school (approximately 40 % of their week-day)(Reference Woodside, Adamson and Spence28), hence, the school-setting is an important environment in influencing adolescent health. Given that, outside of the home, adolescents spend the majority of their time in school(Reference Story, Nanney and Schwartz29), and can consume up to one-half of their daily energy intakes during school hours(Reference Micha, Karageorgou and Bakogianni30,Reference Nathan, Janssen and Sutherland31) , this setting provides a unique opportunity to promote healthy dietary behaviours during this life stage which can be sustained into adulthood(Reference Story, Nanney and Schwartz29), and thus, schools are an important setting for intervention delivery(Reference Hargreaves, Mates and Menon5). School-based interventions have shown promising effects on dietary outcomes, with an increased consumption of fruit and vegetables and reductions in saturated fat and sugar intakes evident among adolescents(Reference Rose, O'Malley and Eskandari32). Moreover, consuming nutritious foods in school has the potential to positively impact academic performance(Reference Anderson, Gallagher and Ritchie33). School-based interventions are also advantageous in that they have the ability to target the whole adolescent population simultaneously(Reference Oostindjer, Aschemann-Witzel and Wang34), regardless of socio-economic background(Reference Vézina-Im, Beaulieu and Bélanger-Gravel35). Thus, schools provide an additional opportunity to access and intervene with adolescents from socially deprived areas who are reported to consume less nutritious diets(Reference Hanson and Chen17,Reference Utter, Denny and Crengle18) , which can aid in targeting a reduction of health inequalities among this population(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones36). By addressing the whole population, stigmatisation among adolescents' weight status can also be minimised. Despite the many benefits of this setting, the most effective ways to utilise schools as a means to encourage healthful dietary behaviours among adolescents has yet to be fully identified and there is a lack of consensus on exactly which school strategies have the greatest potential for positive dietary change(Reference Chaudhary, Sudzina and Mikkelsen37). Additionally, an imbalance exists in the lack of robust evidence from post-primary schools, with systematic reviews highlighting a larger number of dietary interventions conducted in primary schools during 1990–2020(Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Maes and Spittaels38,Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39) , and further research in post-primary schools (targeting the adolescent population) to determine which intervention strategies are most likely to have the greatest impact is highlighted as being warranted(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39).

The school-setting

School food practices vary widely across different countries(Reference Harper, Wood and Mitchell40). However, in the UK, adolescents typically purchase food in school canteens, bring a packed lunch or purchase food from external food environments. Packed lunches(Reference Pearce, Wood and Nelson41–Reference Parnham, Chang and Rauber44) and foods from external outlets(Reference Wyness, Norris and Clapham43,Reference Taher, Ensaff and Evans45) have been associated with less favourable nutritional profiles than meals purchased in post-primary schools (school meals). There is also a lack of existing regulation for packed lunches(Reference Taher, Ensaff and Evans45). Therefore, measures to improve the uptake of school meals among adolescents could prove beneficial in achieving healthier dietary intakes among this population. In Northern Ireland (NI), the complexity of the post-primary school food environment in comparison to primary school settings has been highlighted(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside46). The majority of post-primary schools in NI offer self-service lunch systems, with a variety of food options available as opposed to a set daily menu in primary school(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside46), and thus, adolescents become responsible for making their own independent dietary choices on a daily basis. In an effort to increase and promote nutritious options at lunch time in school, school food standards have been implemented in many countries, including the UK. Although similarities exist in these school-based standards, they vary across each UK region(Reference McIntyre, Adamson and Nelson47). In relation to NI, food-based standards were implemented across post-primary schools in 2007(48), which aimed to provide healthier options for adolescents to purchase. However, there is no guarantee that pupils will choose these(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Van Kleef, Meeuwsen and Rigterink50) , and it is therefore essential that additional motivators for and barriers to healthful food choices within this setting are considered.

Impact of nutritional knowledge on adolescents' dietary choices

When determining how best to improve adolescents' dietary choices within the school-setting, it is important to consider their level of nutritional knowledge and whether they are aware of the healthier food items available to them and their associated health benefits. Both early and more current research indicates that adolescents across several countries possess a good level of nutritional knowledge(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story7,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51–Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55) and have awareness on both the short- and long-term consequences to their health of not consuming a nutritious diet(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story7,Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) . However, it has been highlighted that this level of nutritional knowledge does not always translate into their behaviours and actual choice of food(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Ridder, Heuvelmans and Visscher56) and nutrition is often not a primary consideration when making their dietary decisions(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines57,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58) , with other competing factors which can grant more instant gratification, such as taste, appearance, price and convenience often taking priority(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58) . For example, among US adolescents, taste, hunger and convenience were reported as more influential on their dietary choices than the perceived health benefits of foods(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6). Similarly, in a study with Australian adolescents, food appeal and price were reported to take precedence over the healthiness of the items when purchasing foods in schools(Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58). Moreover, evidence suggests that adolescents' have a low-risk perception of the consequences of consuming an unhealthy diet during their life stage(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6,Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story7,Reference Rose, O'Malley and Eskandari32,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51,Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52,Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59) , and thus, view consuming a healthy diet more important in the future(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6), when health is considered of more relevance(Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55). A study in the Netherlands reported that adolescents felt that it is unnecessary to change their dietary behaviours unless their diet affected their appearance, for example, caused weight gain or impacted negatively on their sports performance(Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52). In NI and Ireland, adolescents reported that they would consider eating a healthier diet if they suffered serious health consequences, for example, became overweight or obese(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51). A further consideration is that, despite adolescents' having good nutritional knowledge, many adolescents categorise foods as ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52) , which overlooks the concept of a balanced diet. In contrast to nutritional knowledge, although environmental food cues, such as the visibility of food items, food accessibility, smell and the dining environment, can significantly impact dietary choices, evidence suggests adolescents' recognition of these influences is limited(Reference Ensaff, Coan and Sahota60).

Factors influencing adolescents' school-based dietary choices

As nutritional knowledge does not appear to be a primary consideration among adolescents, it is important to examine what alternate factors may be influencing their food choices and decisions in school and if any barriers exist to selecting the healthier items available. Gaining an understanding of these factors can aid in the development of effective interventions(Reference Cusatis and Shannon61).

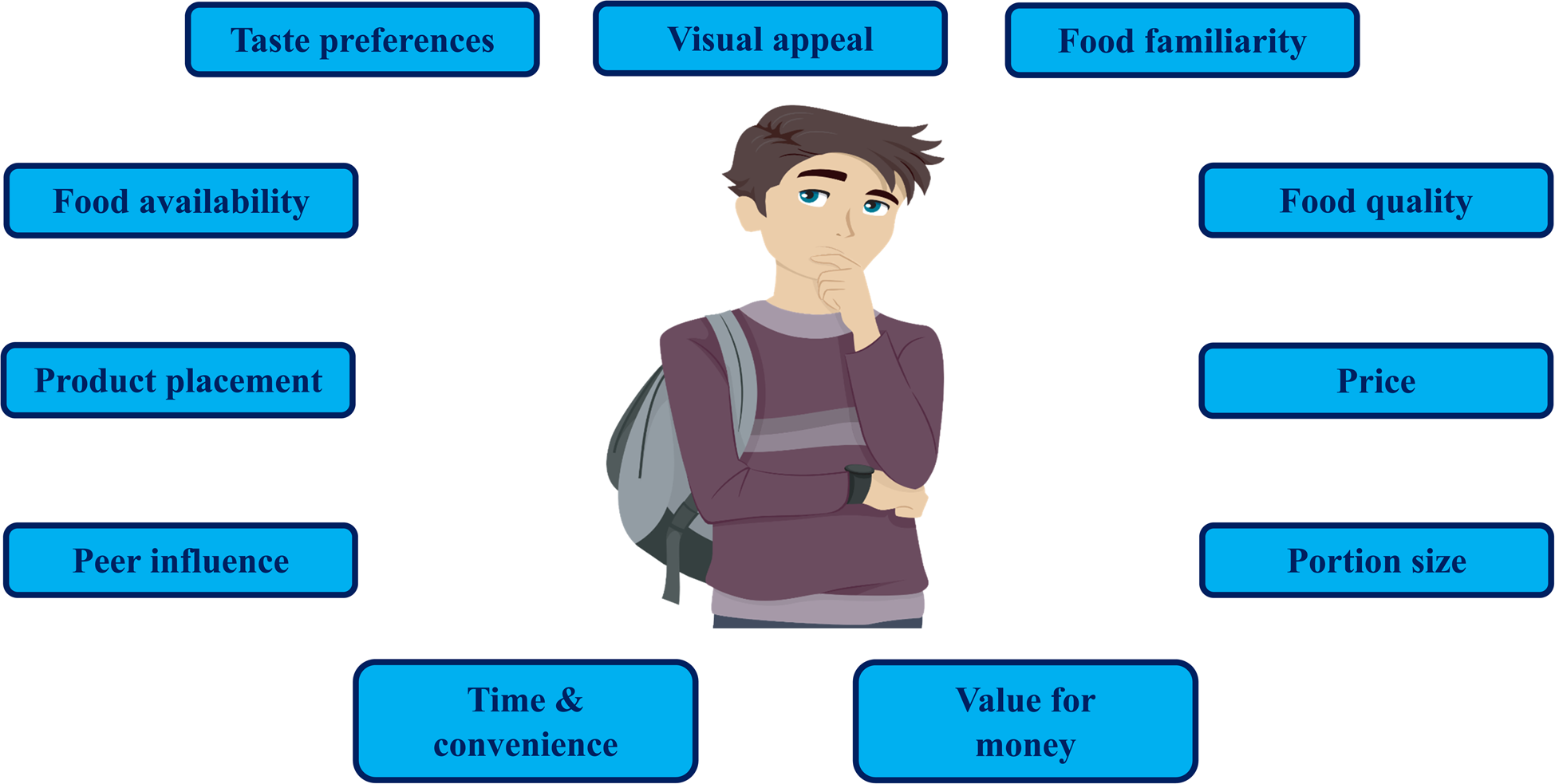

The complexity of the influential factors on adolescents' dietary behaviours has been acknowledged(Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French62), and thus, to aid understanding, the factors can be categorised under four different levels of influence including individual (intrapersonal), social environmental (interpersonal), physical environmental and macro environment(Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French62). Numerous influential factors on adolescents' dietary choices in school have been identified in the literature; however, those commonly reported include individual (taste preferences, visual appeal, familiarity, food quality, price, portion size, value for money, time and convenience), social environmental (peer influence), physical environmental (product placement) and macro environment (food availability) level factors as summarised in Fig. 1. These influential factors will be briefly discussed in turn next.

Fig. 1. Factors influencing adolescents’ dietary choices in the school-setting.

Source of image: BNP Design Studio/Shutterstock.com.

Individual (intrapersonal)

Taste preferences, visual appeal, familiarity and food quality

Taste preferences have been reported as influential in shaping adolescents' dietary choices(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees63,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64) , which can act as a deterrent to selecting a healthier option(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64). The recent UNICEF global Food and Me report(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64) identified that, among 656 adolescents across eighteen countries, perceived taste of healthy foods acted as the second greatest barrier to their consumption of these foods. The influence of taste on adolescents' food choices is also reflected within the school-setting, with adolescents' taste preferences being identified as an important consideration when making dietary decisions in school(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Shannon, Story and Fulkerson65–Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri68) . For example, in a US study, the majority of adolescents (93⋅7 %) reported taste as important when they were selecting food items in the school canteen(Reference Shannon, Story and Fulkerson65). Similarly, in a UK study, taste was reported as a priority among adolescents(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69). Therefore, this may create challenges to encouraging adolescents to choose healthier items in school, as research suggests that adolescents tend to associate healthier options with being of poorer taste(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70) . UK school catering staff have also shared the view that adolescents are seen to opt for the less healthy items and have expressed concerns that excluding these unhealthy foods from the school lunch menu would severely compromise their sales(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71). Therefore, if not offered on menus, adolescents may choose to bring a packed lunch as an alternative to buying food in school(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71), negatively impacting on the financial viability of school canteens. Moreover, UK adolescents and caterers suggested that if healthy items in school tasted better, they would be more appealing to purchase(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69). However, caterers felt that to provide school meals that appealed to adolescents, compromising the healthiness of the meals would be required(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69). In addition to taste, visual appeal(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) , familiarity(Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59,Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari66,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) and quality(Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67) of items served within school have been cited as influential factors on adolescents' food choices. Moreover, dissatisfaction with the quality of school food has also been reported to encourage Scottish adolescents to leave the school premises and source food externally(Reference Wills, Danesi and Kapetanaki74).

Price, portion size and value for money

In the UNICEF global Food and Me report(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64), price was reported as the greatest barrier to adolescents consuming a healthy diet, with financial concerns evident among adolescents in low-, middle- and high-income countries. Research suggests that adolescents also tend to be financially cautious when selecting food and beverage items in school, with price being commonly reported as a key determinant in their purchasing decisions(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69,Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71,Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75) . Adolescents often perceive the healthier options in school as more expensive than the less healthy options(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52,Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69) , which is reported to discourage the purchase of the healthier items in this environment(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69) . In the UK, adolescents reported the less healthy items served in school as cheaper, and thus, more tempting and noted that they are more likely to opt for a fizzy drink as opposed to bottled water as it is less expensive(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53). The recent UNICEF global Food and Me report(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64) recommended that ‘healthy options need to be available at a price that adolescents see as affordable and competitive with unhealthy food choices’, which appears to also be applicable to the school-setting to aid in encouraging the uptake of healthier items. The perceived expense of food and beverages in school can also act as a barrier to the purchase of school meals, encouraging adolescents to opt for cheaper alternatives(Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52,Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55,Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71) or skip their school meal(Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75). For example, Dutch adolescents have reported preference to purchase foods from external supermarkets as they perceived them to be cheaper than their school canteens(Reference Hermans, De Bruin and Larsen52), whereas, UK adolescents have reported opting for a packed lunch as they are viewed to be less expensive(Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55). Moreover, Malaysian adolescents have reported skipping their school meals due to limited money availability(Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75). In addition to price, adolescents' consider portion size(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) and value for money(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Shannon, Story and Fulkerson65,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson76) when making choices on food in school, with preference to opt for foods with higher satiety(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70,Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson76) . In NI, adolescents associated healthier options in school with poor value for money as they perceived them to be more expensive, with lower satiety value(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49), which is similar to a study in Malaysia, where school principals' and catering staff noted that adolescents would opt for the most filling items regardless of their nutritional value(Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70).

Time and convenience

The limited time often available during lunchtime is a concern for UK adolescents, with adolescents choosing to consume food quickly to enable them to utilise any additional time to socialise with peers, play sports and attend lunchtime activities(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77) . These competing factors have been reported to take priority(Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77), and consuming a meal at lunchtime being viewed as a ‘secondary activity’(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69). Additionally, evidence suggests that adolescents also make their dietary choices in the school canteen based on the shortest queue(Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77) , which can restrict their food choices(Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77), and in some cases, research indicates that male adolescents prioritise spending time with their friends as opposed to queueing in the canteen at lunchtime(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49). Long queues in the school canteen also act as a barrier to the selection of healthier options(Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson76) and the consumption of school meals(Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55), and instead encourages adolescents to source items from external food outlets(Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari66) or purchase items at break time to avoid queueing at lunchtime(Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59,Reference Sahota, Woodward and Molinari66) . Adolescents also tend to favour convenient, quick, grab-and-go options when purchasing items in the school canteen(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71,Reference Addis and Murphy78) . The importance of time on adolescents' food choices in school has also been reported further afield, with long queues reported as a barrier to school-lunch uptake among US adolescents(Reference Payán, Sloane and Illum79).

Social environmental (interpersonal)

Peer influence

During adolescence, when time spent with peers increases and parental control tends to diminish(Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French62,Reference Foley, Shrewsbury and Hardy80) , individuals' dietary behaviours can become influenced by their peers(Reference Salvy, de la Haye and Bowker81,Reference Chung, Ersig and McCarthy82) , often impacting negatively on their food choices, with increased consumption of energy-dense foods of a poor nutritional value(Reference Ragelienė and Grønhøj83). The influence of peers on adolescents' food choices is also echoed in research within the school-setting, with school staff(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference Kumar, Adhikari and Li84) , parents(Reference Kumar, Adhikari and Li84) and adolescents(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Ryan, Holmes and Ensaff55,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines57,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73,Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75,Reference Addis and Murphy78) reporting peers to be influential on adolescents' school-based dietary choices. When making dietary decisions in school, many adolescents place importance on social acceptability and conforming to what is considered normal eating behaviours among their peers(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines57,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73,Reference Addis and Murphy78) . This desire for peer acceptance can often impact negatively on adolescents' school-based food choices(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) . For example, UK adolescents reported their male peers as a direct barrier to consuming a healthier diet in school, indicating that they would opt for the healthier options; however, in doing so, they were at risk of judgement, teasing and social exclusion from their male counterparts which deterred them from purchasing these options(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54). The need for peer acceptance can create challenges to promoting a healthy diet in school, as adolescents may be reluctant to opt for healthier items if this does not align with their peer's food norms(Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77). Reframing adolescents' views on the acceptability of healthy eating may potentially aid in the promotion of healthier dietary choices among this population(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54). However, conversely, in a US study, only two out of thirty-five adolescent participants referred to peers as an influential factor on their food choices within the school-setting, with other food-related factors such as taste, quality and freshness dominating their choice preferences within this environment(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri68). Albeit, research suggests that peers may influence adolescents indirectly, as adolescents may have a lack of awareness of the impact of social influences on their diet or due to their increase in autonomy, adolescents can be averse to the concept of others influencing their behaviours(Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French62).

Physical environmental

Product placement

Placement and positioning of food and beverage items in the school canteen has been reported as an influential factor on adolescents' dietary choices(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67) . Studies with UK adolescents have described the situation of healthier options available in their school to be less visible and accessible in comparison to the unhealthy items(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) , acting as a barrier to encouraging healthy dietary choices in this setting(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) . For example, the healthier items have been reported to be placed at the back of fridges(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) or having to stand in a separate queue to source them(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49). Similarly, US adolescents have reported unhealthy items to be more prominently displayed in school, making it challenging to make improved food choices at lunchtime(Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67).

Macro environment

Food availability

Although school food standards have been implemented in many countries to increase accessibility to healthy food and beverages, high exposure to unhealthy items and limited availability of healthier alternatives in school has been reported across numerous countries(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64,Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70,Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75,Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson76,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsely85) , acting as a barrier to healthier eating practices within the school environment(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees63,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64) . Adolescents have shared the view that there is insufficient availability of healthier options provided in school(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70) . In the UK, adolescents have reported feeling they have a lack of choice when selecting foods in school due to the limited availability of healthy items(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54) and have criticised post-primary schools for offering more unhealthy options in comparison to primary schools(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53). Similarly, in Malaysia, adolescents reported temptation for the less healthy items in school due to their large availability and ease of accessibility(Reference Ghaffar, Talib and Karim75). Adolescents have further reported that they view their schools to be providing conflicting messages in regards to healthy eating, as they perceive the food canteen menus are in contrast to the healthy eating promotional messages they receive in school(Reference Ronto, Carins and Ball58) and what they are being taught from an education point-of-view in the school curriculum(Reference Browne, Barron and Staines57,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsely85) .

In addition to these factors influencing adolescents' dietary choices in school and providing insight into some of the challenges adolescents face in selecting the healthier options in this setting, some of these factors can also act as barriers to consuming school meals and stimulate adolescents to opt for a packed lunch or source food from external outlets. This may ultimately lead to school canteens becoming non-financially viable and result in canteen closures, reducing opportunities for researchers and policy makers to access and intervene with this population. Additionally, packed lunches(Reference Pearce, Wood and Nelson41–Reference Parnham, Chang and Rauber44) and food from external outlets(Reference Wyness, Norris and Clapham43,Reference Taher, Ensaff and Evans45) are also often reported to be less healthy lunch sources than school meals. Therefore, by addressing some of these key factors in the school-setting, not only does this provide an opportunity to facilitate improved dietary choices in school, but also potentially increase the uptake of school meals. It must be acknowledged that the majority of included studies are primarily of qualitative methodologies, with several noting the inability to generalise their findings to other adolescent populations as a study limitation(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59,Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67,Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69–Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory77–Reference Payán, Sloane and Illum79,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsely85) . Furthermore, to the authors’ knowledge, there is currently a lack of robust evidence exploring the barriers and facilitators to adolescents' food choices specifically within the school-setting, that are not grouped with other food environments.

Recommendations to improve adolescents' school-based dietary choices

Whilst some studies exploring stakeholder's perspectives on the factors influencing adolescents' dietary choices in the school-setting are evident, less is known on what strategies key stakeholder's, for example, adolescents' and school staff (principals, teachers, caterers), would recommend for implementation in schools to aid in improving adolescents' dietary behaviours within this environment. This can be useful information when designing future school-based interventions, as it increases understanding of the most appropriate school strategies adolescents' may be most likely to engage with, whilst also taking into consideration the feasibility of this to schools, ultimately leading to long-term sustainability with regards to time and financial resources involved for schools.

Despite research suggesting that adolescents' have a lack of concern towards healthy eating during their life stage(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry6,Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story7,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett51) , adolescents across several countries have reported receiving insufficient nutritional education as part of their school curriculum, and thus, have advocated for improvements to be made(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64). Recommendations included receiving more adolescent-specific nutritional information and increased opportunities to learn, for example, practical cooking skills as opposed to theory-based learning(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64). Moreover, much of the nutritional information taught in post-primary schools is within a few academic subjects, which not all adolescents choose to study. Contrastingly, in Ireland, although school staff were supportive of further nutrition education being provided to students, adolescents were less favourable of this concept, reporting that they receive sufficient nutrition education and instead expressed views that attention should be directed towards improving the school-food environment(Reference Browne, Barron and Staines57).

To facilitate improvements in adolescents' dietary behaviours, suggestions have been made to increase the availability of healthier items(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsely85,Reference Melo, de Moura and Aires86) and reduce or eliminate the less healthy options(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49,Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid64,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsely85) served in school. Although adolescents have criticised the low level of healthy(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53,Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54,Reference Gangemi, Dupuis and FitzGerald67,Reference Mohammadi, Su and Papadaki70) and high level of less healthy(Reference McHugh, Anderson and Lloyd53) items provided in post-primary schools, and would welcome greater availability of healthy alternatives(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey54), they also place importance on their own autonomy and value being able to preserve their own freedom of choice in school(Reference Rose, O'Malley and Eskandari32,Reference Addis and Murphy78) , and thus, can be opposed to the concept of banning all unhealthy foods which would stimulate them to source food elsewhere(Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59). For example, UK adolescents have noted that removing the less healthy options in school would encourage them to purchase items from external competitors or opt for packed lunches and suggested that limiting the availability of the less healthy items to one to two times a week, may be a more feasible strategy as opposed to complete exclusion(Reference McSweeney, Bradley and Adamson59). Similarly, UK school staff have reported that the removal of unhealthy items would impact negatively on their sales(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71) and have further commented that they recognise the importance of serving healthy school meals, yet they associated the healthier items with financial implications, such as reduced student uptake, less profits and increased wastage(Reference Murphy, Mensah and Mylona69). Gilmour et al.(Reference Gilmour, Gill and Loudon71) have suggested that a slow and guided transition to removing the less healthy items in the canteen may be possible with support at the governmental level.

Several suggestions to improve adolescents' dietary choices within the school-setting in the UK have been reported. Adolescents(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) and school staff(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72) in NI have proposed incentives as a potential strategy to encourage the selection of healthier items served in the school canteen, with both stakeholder groups recommending recognition, social and financial rewards as suitable incentives for this population. Similarly, adolescents' from socially disadvantaged areas across NI have reported reward schemes as an acceptable approach to improve food choices in school, with adolescents' from rural schools favouring group rewards such as class trips and adolescents' from urban schools having preference for individual-type rewards such as vouchers and clothes(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49). Other initiatives have focused on improvements to the school food environment where adolescents have, for example, advocated for school's to display menus and pricing information in the canteen, amend product placement so healthier items are displayed more prominently and implement labelling schemes, both at the point-of-choice and on school menus(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73). Additional reported suggestions of improvements in school canteens to support healthy food choices include the facility to pre-order food(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73), promotion of ‘special offers’ for the food items deemed to be ‘healthier’(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73), improved marketing(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49), school staff encouragement to eat healthily(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49) and the ability to taste healthy foods before purchasing(Reference McEvoy, Lawton and Kee49). Other suggestions included the ability to offer a ‘meal deal’, increased variety on menus, improvements to school-food (quality and food offered), the promotion of the healthier options and student-led initiatives to facilitate improved dietary choices in school(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72).

Effectiveness of school-based dietary interventions in adolescents

In addition to reviewing the factors that influence adolescents' food choices within the school-setting and the recommendations for improvements, it is also important to consider the success of school-based intervention studies. Despite an increasing number of dietary interventions being implemented in schools, the most effective school-based interventions to improve adolescents' dietary behaviours are yet to be determined and evidence remains limited(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39). Identifying intervention components that show most promise in the school-setting would facilitate larger scale interventions to be piloted and trialled(Reference Woodside, Adamson and Spence28). A range of school-based interventions including the ‘Health promoting schools’ (HPS) initiative, educational, multicomponent, food environment and peer-led, have been conducted to date and their effectiveness are described briefly next (see also Fig. 2). Promising intervention components and study limitations are also highlighted, which should be considered in future research and intervention design.

Fig. 2. School-based interventions aiming to improve adolescents’ school-based dietary behaviours.

Source of image: Kwang Chanakarn/Shutterstock.com.

Health-promoting schools approach

A HPS is defined by the WHO as a school that ‘constantly strengthens its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning and working’(87). The HPS framework was developed in the 1980s(Reference Turunen, Sormunen and Jourdan88) and recognises the intrinsic link between education and health(Reference Langford, Bonell and Komro89). This framework advocates for a ‘whole-school’ approach to improve adolescent education and well-being(Reference Macnab, Gagnon and Stewart90), and involves health promotion via the school curriculum, adjusting the school's social or physical environment, which can include the school canteen, and increased family and community engagement on the topic of health(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones91). The HPS concept has been positively received and implemented in many countries(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones36) and the WHO has encouraged schools worldwide to adopt this approach(Reference Macnab, Gagnon and Stewart90).

A systematic review (SR)(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones36) exploring the impact of the HPS framework on improving health and educational outcomes in pupils in primary and post-primary schools (aged 4–18 years), reported that nutrition interventions following the HPS framework showed positive effects on increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, with an average increase of 30g daily, albeit, were ineffective in reducing fat intakes. However, the majority of studies in this review targeted children (<12 years), with a lack of nutritional interventions conducted among the adolescent population and this review did not report on adolescents in isolation(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones36). A more recent SR(Reference McHugh, Hurst and Bethel92) examined the effectiveness of interventions utilising the HPS framework in promoting physical activity and a healthful diet among adolescents (11–18 years) independently and reported no effect of HPS nutrition-only interventions on adolescents' fruit and vegetable intakes. Four nutrition-specific interventions were included in this review, with two studies(Reference Foster, Sherman and Borradaile93,Reference Hoppu, Lehtisalo and Kujala94) reporting minor positive outcomes. For example, Hoppu et al.(Reference Hoppu, Lehtisalo and Kujala94) showed that the incorporation of HPS components resulted in a reduction in the percentage of energy intake from sucrose (decreasing 2⋅3 %) and the consumption of sweets among adolescents in the intervention. However, this intervention study only targeted pupils in the eighth grade (average 13⋅8 years at baseline), and thus, results may not be applicable to all adolescents(Reference Hoppu, Lehtisalo and Kujala94). However, overall this SR(Reference McHugh, Hurst and Bethel92) concluded that HPS nutrition interventions had limited impact on improving adolescents’ dietary behaviours. It must be noted that in this review(Reference McHugh, Hurst and Bethel92), heterogeneity was evident among the study designs, nutrition HPS-based interventions were rated as low quality and studies were lacking among the adolescent population, including adolescents aged 11–15 years, with no studies being conducted with the older adolescent age group (16–18 years).

Educational vs multicomponent interventions

Other intervention studies have solely focused on school-based educational approaches when aiming to improve adolescents' dietary behaviours. However, educational interventions are reliant on making deliberate dietary decisions which doesn't take into consideration the automatic nature of making food choices(Reference Ensaff95). An earlier SR(Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Maes and Spittaels38), exploring European studies among adolescents (aged 13–18 years) reported moderate evidence of effect of educational interventions on promoting a healthful diet among this age group. This review included six education-only interventions targeting adolescents [UK (n 3); Belgium (n 1); Norway (n 1); the Netherlands (n 1)] and were published during 1993–2008, of which the majority of interventions utilised activities in the classroom, for example, amendments to the curriculum and providing education-based materials(Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Maes and Spittaels38).

More recent evidence suggests that school-based multicomponent interventions may be more effective than education-only interventions in achieving positive dietary change among the adolescent population, with a recent SR of systematic reviews(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39), which included three systematic reviews on educational interventions and dietary behaviours in adolescents, reporting success among education-based studies if specific components were also incorporated into the interventions. For example, Meiklejohn et al.(Reference Meiklejohn, Ryan and Palermo96) explored the effect of multi-strategy educational interventions (combination of nutrition education with additional strategies) on adolescents’ (10–18 years) health and nutritional behaviours. This review included eleven studies from Sweden (n 1), Belgium (n 1), Finland (n 1), Greece (n 1), Norway (n 2), the Netherlands, Spain and Norway (n 1), Australia (n 2) and the USA (n 2) and reported positive dietary outcomes among studies (n 9) when educational interventions included complementary components, for example, school staff facilitating the intervention, involving parents, amending the food environment in school and if the intervention is guided by theory(Reference Meiklejohn, Ryan and Palermo96). Additionally, a SR conducted by Murimi et al.(Reference Murimi, Moyeda-Carabaza and Nguyen97) reported that multicomponent nutritional education interventions in post-primary schools were more likely to succeed if some intervention characteristics included, for example, engaging with parents and utilising technology. Overall, the SR of systematic reviews(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39), reported that, five systematic reviews concluded multicomponent interventions (combination of educational and environmental changes) to be more successful than interventions solely adopting educational approaches.

Food environment interventions

The school food environment has been proposed as a way of improving food choices in school(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73,Reference Kubik, Lytle and Hannan98) . The school food environment and the concept of choice architecture, commonly referred to as nudging, behavioural economics or libertarian paternalism(Reference Bucher, Collins and Rollo99), is emerging as a promising strategy to modify adolescents' dietary behaviours in the school-setting. Food choice architecture refers to how food choices are framed and how this impacts on food selection(Reference Ensaff, Homer and Sahota100). It nudges individuals towards particular dietary choices via subtle, low-cost changes to the food environment(Reference Ensaff95,Reference Ensaff and Altieri101) . Ultimately it involves making the preferred choice, the easiest choice without eliminating food options, thereby, maintaining freedom of choice(Reference Ensaff95). Different food choice architecture strategies have been employed in schools to encourage positive food choices which include making amendments to the attractiveness of foods displayed, the visibility of specific food items and their convenience(Reference Quinn, Johnson and Podrabsky102). More specific food choice architecture intervention components are outlined in Fig. 3 and reviewed by Ensaff(Reference Ensaff95). Food choice architecture interventions have shown promising outcomes for improving adolescents' dietary choices in post-primary schools. For example, the incorporation of complementary food choice architecture components into a UK post-primary school canteen, such as amending product placement, introducing labelling strategies, promotional posters and increasing convenience, resulted in adolescents being 2⋅5 times more likely to opt for the promoted items (whole fruit, fruit pots, vegetarian specials and salad-based sandwiches) and 7⋅5 times more likely to opt for salad items specifically during the intervention period when compared to baseline(Reference Ensaff, Homer and Sahota100). Outcomes in this study were based on sales of food as opposed to consumption data(Reference Ensaff, Homer and Sahota100). Furthermore, the effect of the intervention components were reported on collectively, and therefore, the impact of each individual component remains unclear and it is difficult to interpret if one change in the choice architecture was more successful than the others(Reference Ensaff, Homer and Sahota100). More recently, Spence et al.(Reference Spence, Matthews and McSweeney103) delivered an intervention in two UK post-primary schools, which focused specifically on amending product placement by increasing the accessibility of healthier (fruit and water) and reducing the accessibility of the less healthy (sweet-baked goods and sugar-sweetened beverage) items in the canteen setting at lunchtime. Spence et al.(Reference Spence, Matthews and McSweeney103) reported positive outcomes on pupils’ food and beverage purchases in both school A (increase in fruit pot purchases; decrease in sugar-sweetened beverage purchases) and school B (decrease in sweet-baked goods and sugar-sweetened beverage purchases). Overall, the authors concluded that there is some limited evidence that product placement interventions may positively impact pupils’ food and beverage purchasing decisions(Reference Spence, Matthews and McSweeney103). Additionally, a recent SR(Reference Metcalfe, Ellison and Hamdi104) aimed to assess the effectiveness of school nudge interventions on pupils' dietary behaviours in the school canteen. This review included twenty-nine studies from the USA (n 26); Australia (n 1); France (n 1) and the UK (n 1) and nudge interventions were categorised as: marketing/ promotion; placement/ convenience; variety/ portion sizes; multicomponent (studies with >1 intervention component)(Reference Metcalfe, Ellison and Hamdi104). This review(Reference Metcalfe, Ellison and Hamdi104) reported a positive association between school nudge interventions and pupils' food selection; however, conclusions are based on studies conducted across both primary and post-primary schools. Another SR(Reference Nørnberg, Houlby and Skov105) examined the effectiveness of choice architecture nudge interventions on promoting vegetable intake among adolescents specifically in school. This review included twelve studies [USA (n 9); Canada (n 2); Europe (n 1)], with interventions to promote vegetable intake among adolescents including amendments to the serving style and physical environment and free vegetable distribution, however, findings were inconclusive(Reference Nørnberg, Houlby and Skov105). Heterogeneity was noted across the studies intervention type and outcome measures, the majority of studies were reported as low or moderate quality and vegetables did not appear to be a primary focus among interventions(Reference Nørnberg, Houlby and Skov105). This SR(Reference Nørnberg, Houlby and Skov105) also highlighted that none of the included studies explored adolescents' attitudes towards the choice architecture nudge interventions, limiting understanding of adolescent's acceptability towards these types of school strategies. Given the potential nudge-based interventions offer in facilitating improved dietary practices within schools, a recent WHO policy brief(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101) aimed to raise awareness of the opportunities in which nudge strategies could be implemented within the school-setting, for example, in the school canteen, food vending machines and tuck shops. This policy brief(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101) also outlines the rationale and evidence for school-based nudge strategies and provides a step-by-step guide for developing and implementing nudges within the school environment(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101). Although nudge-based interventions in the school-setting show promise, this policy brief(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101) also highlights their associated challenges and limitations, reporting that mixed findings are evident, and more research is needed to determine their long-term effects. Moreover, there is limited evidence among low- and middle-income countries, with the majority of studies to date being conducted in Europe and the USA(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101). Variation between schools should also be considered, with the WHO policy brief outlining ‘proposed nudges should be developed, as appropriate, to the specific context; that is, one size does not fit all and actions will vary between individual schools’(Reference Ensaff and Altieri101).

Fig. 3. Choice architecture intervention components.

Source: Fig: ‘Nudge strategies implemented in choice architecture interventions to change food choice: reducing effort and cognitive load, increasing salience and emphasising tastiness and social norms.’ Ensaff(Reference Ensaff95).

Peer-led interventions

Peer-led, school-based nutrition initiatives have the potential to improve dietary attitudes, knowledge and self-efficacy(Reference Yip, Gates and Gates106), and therefore, peer-led interventions in school are also receiving increasing attention as an effective means to promote improved dietary behaviours among adolescents. It has been suggested that when targeting adolescents' dietary behaviours, adolescent-led interventions may increase effectiveness as they may be more aware of this population's values(Reference Evans107). Peer involvement has been reported as an important contributing factor to the success of school-based dietary interventions among adolescents and should be considered in future intervention design(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey19,Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39) . For example, in a SR(Reference Calvert, Dempsey and Povey19) examining the effectiveness of in-school interventions aiming to improve adolescents (11–16 years) dietary behaviours, nine studies included peer involvement, all of which were successful in promoting positive dietary change among this age group, with the majority of these studies (n 5) receiving a quality rating of moderate to strong. Similarly, Foley et al.(Reference Foley, Shrewsbury and Hardy80) also reported that peer-led interventions in school can also promote improved dietary intakes among peer-leaders (15–16 years) involved in the delivery of the intervention to younger students in their school (13–14 years). Involvement in this study also appeared to be highly acceptable to participating peer-leaders, as following completion of the study, when asked if they would recommend the intervention programme to others, 91 % of those involved reported that they would(Reference Foley, Shrewsbury and Hardy80). The authors have recently completed a peer-led, school-based pilot feasibility study in NI aiming to promote healthy dietary choices among adolescents (11–12 years). Further details on the pilot study is outlined on the Generating Excellent Nutrition in UK Schools website(108).

Additional intervention components

A recent SR of systematic reviews (n 13)(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39) on dietary interventions among adolescents (11–18 years) in post-primary schools identified several promising intervention components that are worth consideration in future interventions aiming to improve dietary behaviours among adolescents in school. In addition to peer involvement and multicomponent interventions, this SR(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39) recommended utilising approaches such as increasing the availability of healthier items in school, involvement from parents and incorporating ‘age-appropriate’ strategies, for example, computer-based feedback and multimedia to aid in potentially improving the success of future dietary interventions targeted at this population. This SR(Reference Capper, Brennan and Woodside39) also highlighted that the majority of included systematic reviews received a ‘low’ (n 7) and ‘critically low’ (n 3) quality rating, therefore, Capper et al. cautioned interpretation of these findings. Another SR(Reference Sacco, Lillico and Chen109) examined the effectiveness of menu labelling in the school canteen to aid with adolescents' dietary choices and showed positive results in two out of three studies. Conklin et al.(Reference Conklin, Cranage and Lambert110) reported that nutritional labels placed at the point-of-selection in the school canteen resulted in adolescents opting for items with lower energy and fat content. Similarly, Hunsberger et al.(Reference Hunsberger, McGinnis and Smith111) reported that displaying energy labels at the point-of-purchase resulted in an average energy decrease of 47 calories and 2⋅1g of total fat among adolescents (11–15 years). Although these studies(Reference Conklin, Cranage and Lambert110,Reference Hunsberger, McGinnis and Smith111) reported positively influencing adolescents food choices in the school canteen, both studies were conducted within the USA and Sacco et al.(Reference Sacco, Lillico and Chen109) acknowledged their methodological limitations and classified these studies of ‘weak’ quality. Researchers in the UK have considered a variety of different ways to improve adolescents' dietary choices within the school-setting. In NI, Rooney et al.(Reference Rooney, Neville and Hanvey112) reported high acceptability of a rewards-based intervention to encourage healthier food choices among adolescents (12–14 years) in school canteens. Similarly, Devine et al. undertook qualitative interviews(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72) and focus groups(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) with school staff and adolescents respectively, in which initiating student-led initiatives(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72) and providing incentives(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) were some examples of appropriate strategies suggested to facilitate adolescents' making improved dietary decisions within the school canteen. These qualitative findings(Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill72,Reference Devine, Gallagher and Hill73) , informed the design and delivery of a peer-led, school-based pilot feasibility study(108) which included incentives, for example, social and financial rewards, as one of the study components to encourage the selection of healthier items served in the school canteen.

Conclusions

There is an urgent need to improve nutritional intakes among the adolescent population to aid in achieving better health outcomes. Adolescence presents a key time to intervene when individuals are developing a greater sense of autonomy and exercising increased independence when making their dietary choices as they transition towards adulthood and schools therefore provide an ideal setting to access and promote positive dietary behaviours among this particularly vulnerable group within a controlled environment. Adolescents' dietary behaviours within the school-setting are complex and multifactorial. Therefore, gaining a holistic view by identifying the main factors and barriers which influence adolescents' food choices in school is important for researchers and policy makers to consider as they approach the design of future interventions. Whilst evidence is available on the factors influencing adolescents' dietary choices, more research on adolescents' and school staff's suggestions on how best to address these barriers using school-based strategies in the development of future interventions would be worthwhile. Moreover, to build on the current evidence and aid in establishing best practice in schools, future research should direct attention to the intervention components which show most promise and address the current methodological limitations and research gaps present in school-based dietary interventions. Ultimately, generating an evidence-base with which to inform and enhance the development of future successful school-based interventions will help ensure such interventions are feasible, tailored to the target population and optimise outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Irish Section of The Nutrition Society for inviting the present review paper as part of the postgraduate review competition.

Financial Support

This work was undertaken as part of a PhD scholarship funded by the Department for the Economy and the peer-led intervention undertaken in schools(108) was supported by a grant from the UK Prevention Research Partnership (UKPRP) Generating Excellent Nutrition in UK Schools (GENIUS) Network.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

L. D. D. drafted the manuscript. A. J. H. and A. M. G. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.