Yve Laris Cohen’s Studio/Theater, an installation at the Museum of Modern Art, hinges on the fate of two theatres. The first: the newly constructed Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio. Part of MoMA’s multiyear expansion and renovation project, MoMA’s Studio is neither a theatrical black box nor a white cube gallery. Instead, the flexible space integrates live performance with their exhibitions and permanent collection. Laris Cohen’s second theatre, the Doris Duke Theatre at Jacob’s Pillow, was not philanthropically assembled so much as hosed down, having burned, in 2020, in an electrical fire. Studio/Theater transports portions of the Doris Duke’s refuse—a segment of scorched facade, some structural pipes—into the Kravis Studio: a theatre within a theatre within a museum. Yet Laris Cohen’s two performances, Conservation and Preservation, alternating weekly from 1 October through December 2022, slyly pressured the ontological security of each performance site. In the interval between two theatres—one host, one parasite; one functional, the other remaindered—Laris Cohen produced more theatres still.

Figure 1. Lynda Zycherman and Yve Laris Cohen in Conservation by Yve Laris Cohen at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. 8 October 2022 –1 January 2023. (Photo by Oresti Tsonopoulos; courtesy of Yve Laris Cohen)

Conservation and Preservation utilize a set of theatrical techniques—such as stage lighting, backstage communication headsets, and rigging—to re-compose the Doris Duke within the structural parameters of their newfound performance site. Yet asking a theatre to perform as an object in another theatre risks a kind of theatrical redundancy. For his misé-en-scene, Laris Cohen halved and folded the Doris Duke facade, wedging the detritus between two flanking entries to the Kravis Studio. The burned facade effectively blocks off the theatre’s open-plan access to the galleries—performing as functional architecture, which it is not. The pipes suffer a similar fate. When I enter Conservation, they curl around the floor, mimicking, helplessly, the shape of MoMA’s operational overhead grid, to which they are affixed by a set of cables. Those cables run into a winch, bolted into the floor. Laris Cohen spends the performance on his knees, turning the handle counterclockwise, slowly manipulating the height of the gnarled, rusted pipe grid. In Preservation, he lowers the grid at a steady rate from the theatre ceiling to the ground; in Conservation, he raises it. When the grid hits the ceiling with an audible click, the performance ends. So the burned theatre hitches a ride on its functional counterpart like a parasitic, broken down double, or one ton of dead weight. The first etymology of performance is, after all: to carry, to carry out.

Having trained across multiple mediums—ballet, theatre, sculpture, and installation—Laris Cohen’s artworks often take the form of an inquest around the ontology of an object, be it a performance prop, a set of institutional policies, a labor contract, or a situated building, exploring how discursive conflict makes and remakes the given. Yet his obsessive, questioning speech, rather than clarifying or even describing any object, often mystifies it, playing on incongruities among aesthetic, institutional, and legal fields. Fine (2015), held at The Kitchen in New York, uncovered, in forensic detail, a sculptural performance object Laris Cohen would not be allowed to build. The 40-foot sprung, raked stage, reoriented as a wall, set to inch toward the audience during the performance, boxing them in, was too expensive, said The Kitchen. It was too heavy, said the engineers, and should it topple, too risky. Laris Cohen, frustrated and grieving, having sunk his budget into the wall, choreographed those architects, engineers, and technicians back into his performance, gently, persistently asking why the wall had not come to be. Each explained differently. Fine reconstituted the wall first as impossibility, then as collective utterance. Language performed in the wall’s stead.

In Preservation and Conservation, Laris Cohen is again the questioner. He calls in a series of institutional specialists one after another as the pipes fall (Preservation) or rise (Conservation) by the turn of his arm. Preservation features affiliates of Jacob’s Pillow. In Conservation, a MoMA sculpture conservator, Kravis Studio theatre consultant, National Park Service architectural conservator, and chair of the Conservation Center at the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU act as performers among a tangle of wreckage. Under the pipe grid and before the burned-out wall facade, Laris Cohen invites them to speculate, first, what happened to, then how to safeguard, the Doris Duke’s remains—now, his artwork.

Though their title suggests a promise to keep or even embalm, conservators, necessarily, are experts in decay. As a profession, they train to identify traces of wood-devouring termites in an object, or museum pests like silverfish. Conservators note the temperature and humidity of storage facilities, stabilizing precious materials with climate control. When damage comes, and it always comes, they make their recommendations: UV-light treatment for mold exposure, epoxy to stabilize a fraying end, tarp to protect against a leaky ceiling. Conservators learn the arts of bone, wood, hair, metal, rust. Their gentle handling secures an art object’s future on behalf of the museum, underwriting the museum’s promise to preserve art intact. Yet no object of conservation is a settled affair. Peering around the pipes, one conservator conditionally, albeit deftly, provides the timescale of their decay. Objects disintegrate more quickly in certain environments, she explains. Rusted iron might take hundreds of years to disintegrate in a good environment, but in 50 years, Laris Cohen’s installation could no longer be hung without collapsing. The pipe’s sharpest angles—here, the conservator gestures toward her favorite—would be the most at risk. Next, Laris Cohen calls in a theatre engineer, who explains the functioning machinery of the Kravis Studio, indexing, implicitly, the distance of the wall and pipes from durable institutional support, on which they, literally, hang. In a question that limns MoMA’s renovation and the display of the Doris Duke’s once-functional body, Laris Cohen questions a conservator about reconstruction. When are remains displayed, he asks, and when are missing parts reproduced? The conservator’s answer hinges on the lost leg of a painted wood figure. I’d refabricate that leg, she insists, as a structural necessity—if the figure were exhibited upright and standing. Conservators can make a skeleton perform.

Some say that theatre is alive because it ends; others attribute that life to its living performers, who also end. Others say the theatre lives because its actors suffer, and it’s true—why else give yourself away for repetition, on behalf of an artwork you do not own or a play you do not author, but merely enact in a long chain of pathetic, heroic succession? Theatre’s vitality has less often been attributed to theatre architecture, like its walls, pipes, cables, and floors—nor have those structural supports been imbued with their own capacity to live or die. Such organicism has been more readily attributed to sculpture. Yet the life and death of sculpture has folded back into the question of the theatre, or theatricality, in uncanny ways. For art critic Michael Fried, certain minimalist sculptures—in their organic temporalities, interdependent site-specificity, and attachment to decay—left the transcendent realm of visual art, entering the corporeal apparatus of theatre ([1967] 1998). Laris Cohen, in turn, insists on the theatricality of minimalist sculptures sourced from the theatre itself—the remains of the Doris Duke not only perform, but perform theatrically, as art objects. As objects, they are neither visual art nor theatrical props, sculpture nor installation, but a kind of refuse that performs. One could say, easily, that the Doris Duke Theatre died in a fire. It was a spectacular and witnessed death, attended by firefighters, telecommunications crews, journalists, mourners. After, the snow buried her. A few picked over her remains for valuable parts, including Laris Cohen. In the MoMA theatre the expert in metal casts her eye around the Doris Duke’s burnt, twisted pipes, rusted from the firefighter’s hose and the Massachusetts snow, and asks Laris Cohen if he had resized, i.e., cut them to fit into MoMA’s Kravis Studio. All but one have “natural ends,” Laris Cohen says—a Freudian slip, describing a kind of death. Yet the pipes are not the only objects ensouled by suffering. Midway through the performance, as the pipe grid hangs mid-height, Laris Cohen calls in an expert from the MoMA Conservation Center. She describes a parallel fire. In 1958, during yet another renovation of the museum galleries, a worker dropped a cigarette on a drop cloth. Paint cans nearby went up in flames. Entering the building axe-first, a firefighter hacked through a panel of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies. I wince at the doubled cut, building and painting both.

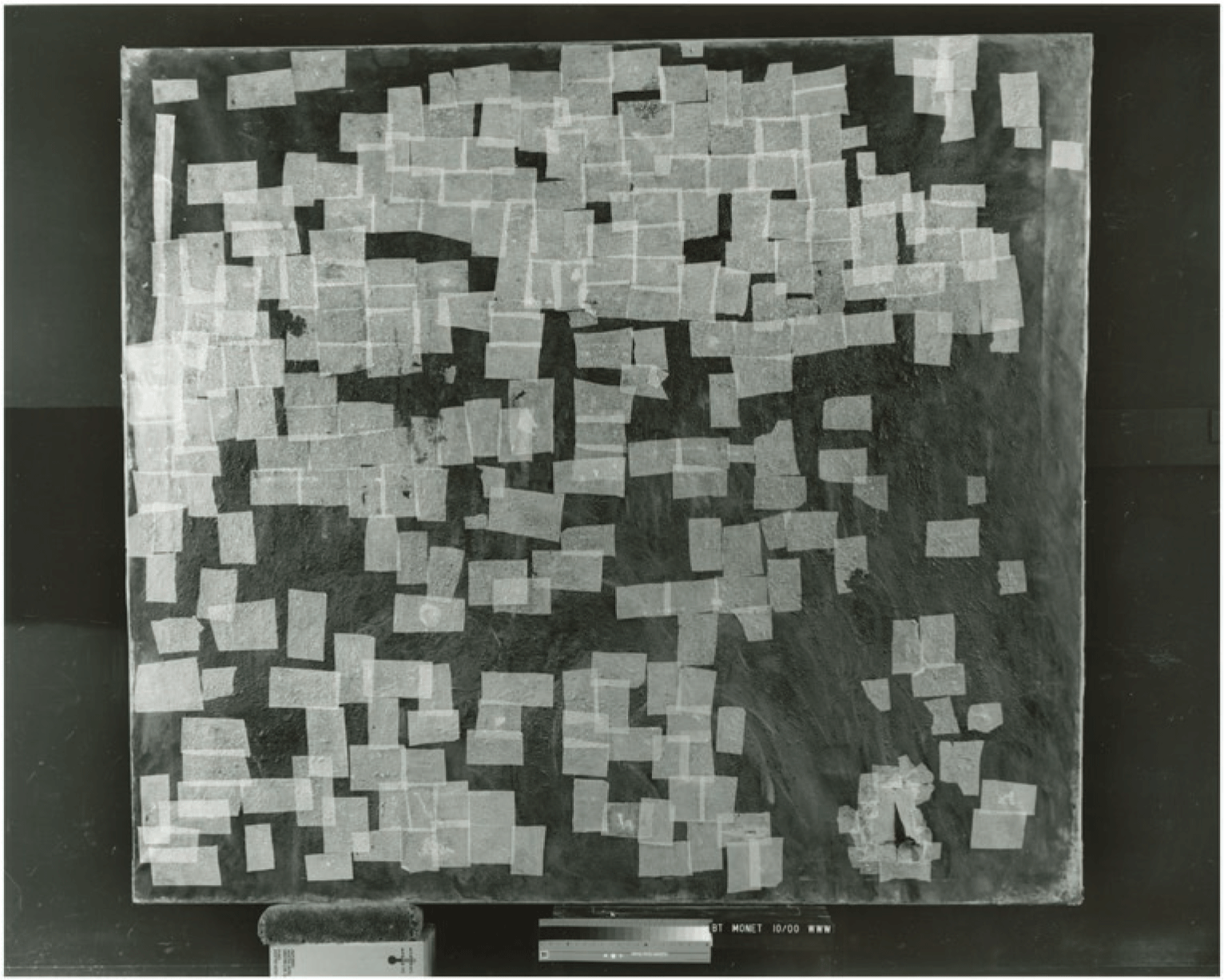

Laris Cohen texted me a picture of the Monet last month. He had wanted to use the artifact in his performance but had been disallowed by MoMA. He wonders, as he has often done, what his performance could be without institutional policy. In my phone, the Water Lilies panel is charred, black, held together by squares of facing tissue, sutured almost, like a craft project. The Monet reminds me of a Mondrian, if Mondrian worked in a furnace, then tried his hand at repair. Laris Cohen tells me that MoMA created the Conservation Department as a result of the fire, hoping to cut down on costs by restoring the paintings in-house. The Monet, however, was beyond repair. Insurance reimbursed MoMA for the lost artwork, but at the completion of the wire transfer, the Monet could no longer be, either legally or institutionally, art. It was no longer a Monet, or for that matter, a painting. Untitled and out of circulation, that Monet or not-Monet or not-not-Monet was eventually absorbed by the IFA’s Conservation Department. There, the object has for years been stored and repaired, worked over and learned from, by student conservators-in-training Laris Cohen could not, for institutional reasons, display the “Monet,” combining the refuse of the two fires in one theatrical house. Instead, many experts speak on the object’s behalf, though that object in fact preceded their expertise, called their expertise into being.

Figure 2. Photo of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies panel, charred, black, and held together by facing tissue after the fire. (Photo courtesy of Michele Marincola and the Conservation Center at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University)

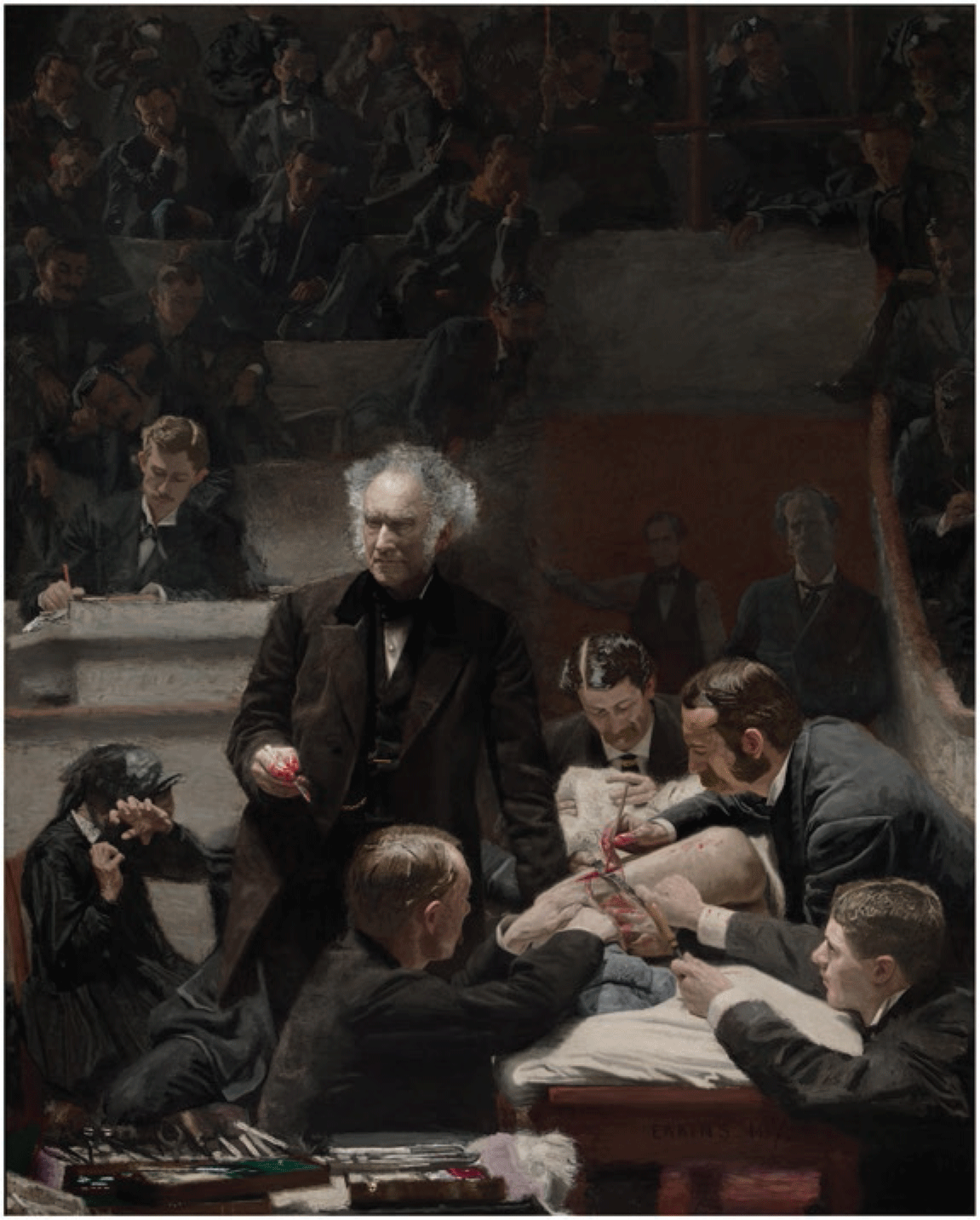

Under the rising pipe grid, conservators speak about the remains of both Jacob’s Pillow and the Museum of Modern Art, demonstrating with cool ease the knowledge that can be made in disaster’s wake. Theirs is the knowledge born in the midst of decay, which prevents decay, which repairs it, and—this is crucial—does so on behalf of those institutions that promise to sustain the object vis-à-vis categorization, valuation, and proper control. Still, the objects remain unstable. Are the pipes metal? Language transforms them to bone, tissue, or organ. One conservator refers to the pipes as stenosed by the heat of the fire. But the term emerges from medical literature to describe a constricted artery or intestine. Recording the disaster, yet another performer, a court stenographer, plunks away on her machine in the corner of the theatre, a presence that confirms the performance’s linguistic afterlife. So we are not only in a theatre-as-minimalist sculpture, or a theatre-as-art object, or a theatre-as-supplement, -parasite, or -ornament. We are also in a juridical theatre, an educational theatre, perhaps an anatomical or operating theatre, like those in early medical universities, organized around the theatricality of a corpse. In a dim room, lit by a surgical light, doctors speak as they cut into a body. Students arranged in a tiered audience look on, rendering the dissection a spectacle. Without consciousness, the body remains an object, not a subject, of medical address—absent from what happens, though it happens on them, in them, and on their behalf (Bleeker 2008). I cannot say whether surgeons, like conservators or curators, hear the speech of their objects. I do know that theatre has its own approach to the logic and location of language. And objects, as Karl Marx understood, speak theatrically—defying proper transmission with a strange ventriloquism (Marx [Reference Marx1867] 1990:176–77; Moten Reference Moten2003). The pipe grid hangs from the functional theatre like a marionette doll, both objectified and ensouled.

Figure 3. Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875, by Thomas Eakins. Oil on canvas, 8´ x 6´6˝. Gift of the Alumni Association to Jefferson Medical College in 1878 and purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007 with the generous support of more than 3,600 donors, 2007. (Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Of Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, Derrida wrote, “whatever can be said of the body can be said of the theatre” ([1967] 1978:232). He did not mean that theatre architecture was alive, only that theatre held Artaud’s delirious need to restage a body stolen from him—disassembled, disarticulated, cut. “Please send in Lisa,” Laris Cohen says. By that time the performance is nearly over. He is tired from turning the winch, not just tonight but once a week for several months. The pipes have nearly reached the ceiling of the theatre where they sit, precipitously, above us. Death, I guess, suspended by a single thread. Despite the testimony of experts and their speculative timelines, its fall is imminent. Lisa, whom Laris Cohen has summoned, walks by me, unmasked, in a white lab coat. I do not recognize her even as she takes her designated position under the pipe grid, surrounded by the audience. As she says her last name “Malter” I struggle to breathe, then openly cry, beside Laris Cohen’s brother, thanking the KN95 mask for covering my face. We are reenacting Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic (1875), that painting which preserves a woman’s horror as her kin is opened on a surgical table. Lisa Malter is a doctor of Gastroenterology at Bellevue Hospital. Years ago, I sat across from her as she introduced my partner of seven years, Yve, to his diagnosis, one which necessitated a surgery, then another, in a series of accelerating, death-defying acts. Now Yve questions her about post-traumatic stress disorder, and I’m seized by an image of the MoMA fire. Workers form a human chain through a flooding gallery to remove and save the paintings. Firefighters resuscitate other firefighters. A woman at the tail end or perhaps deepest point of that human chain, who cannot see in the smoke-filled gallery, moves instead along the walls by frantic touch. She feels for the surface of paintings, choosing which will live or die, conserving without instruction. Artworks emerge from the building one by one, hand-to-hand. Crisis had made the museum a theatre. If the body of the artist is also a theatre, as Artaud envisioned, I imagine Yve’s body cut and wide and us carrying out artwork after artwork, running away with them as he collapses.