1. Introduction

Since 2015, the Canadian Senate has undergone the most radical period of transformation in its history. The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau, elected in 2015, has implemented a broad set of changes meant to address some of the perennial critiques related to the Senate. These changes led to the creation of several new nonpartisan caucuses, including the Independent Senators Group (ISG), which now holds a plurality of seats in the Senate; the replacement of the government caucus and leadership team in the Senate with a Government Representative Office (GRO) of three ostensibly independent senators; numerous modifications to the internal rules and orders of the Senate to reflect its changing membership; and at the root of this transformation, an Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments (IAB).

The Senate reforms were introduced in the wake of a series of scandals that rocked the chamber from 2012 to 2015. The main area of concern was related to improper expense claims on the part of senators from all parties. However, the Senate is a historically controversial institution, and the expenses scandal reignited many of the long-standing concerns about the chamber. In response, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper (in office from 2006 to 2015) redoubled its efforts to implement a series of reforms to the Senate that would limit senatorial terms and allow for popular input into the selection of senators through consultative provincial elections. This reform agenda was stopped short by the Supreme Court in a 2014 decision, Reference Re: Senate Reform (hereafter the 2014 Senate reform reference), in which the court ruled that unilateral reforms on the scale proposed by the Harper government would need the consent of the provinces (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2019).

At the time of this ruling, the Liberals under Justin Trudeau had a sizable Senate caucus and thus were able to take a practical step toward Senate reform despite not being in government. In January 2014, Justin Trudeau removed all Liberal senators from the Liberal parliamentary caucus and encouraged them to sit as independents. While many of the senators instead chose to form a Senate Liberal Caucus (SLC) distinct from the wider party, this decision foreshadowed Trudeau's actions once he came to power after the 2015 federal election. The Trudeau government introduced a series of reforms that were intended to make the Senate less partisan and more independent. The government promised that the new appointment process would lead to a more independent chamber that reflected the diversity of Canadians (Trudeau, Reference Trudeau2015). This reformed Senate was expected to be more legitimate and more active in the legislative process.

The reform of the Senate over the last few years has created a unique opportunity to examine an institution in a period of unprecedented change. We address three closely related questions: First, does the legislative behaviour of senators in the reformed Senate suggest increased independence from their legislative groups? Second, does their behaviour suggest that they are ideologically diverse? Finally, have senators become more willing to use their formal legislative powers? To answer these questions, we turn to the entirety of the recorded Senate votes of the 41st and 42nd Parliaments. Drawing on established measures of legislative independence and ideology, we measure how these have been changed by the reforms. We then turn to legislative data from that same period to measure the Senate's relative strength.

2. The Senate in Theoretical Perspective

Upper chambers around the world are extremely heterogeneous, differing in their powers, methods of selection, terms of office and constitutional roles. Nevertheless, bicameral legislatures (that is to say, legislatures with two distinct chambers) broadly serve two primary purposes: first, to provide enhanced representation to minority groups that are outnumbered in a representation-by-population lower chamber; and second, to provide redundancy or legislative review (Patterson and Mughan, Reference Patterson, Mughan, Patterson and Mughan1999).

Smith (Reference Smith2003) argues that the bicameralism is a “concept in search of a theory,” lacking a clearly articulated, widely accepted justification, which in turn has resulted in an inability to arrive at a reform consensus. Nevertheless, we argue that the Senate's institutional configuration and historical reform proposals have both largely reflected the two purposes outlined above.

The Trudeau Senate reforms address this first purpose of bicameralism through their requirement for increased gender and racial diversity in Senate appointments. The first function of upper chambers, the protection of political minorities, overlaps importantly with the second, the provision of legislative review, since one of the main ways in which the Senate can promote minority interests is by amending or defeating legislation. Yet redundancy is more than simply a method of minority rights protection: it also ensures that legislation is tightly crafted, considers a broad array of perspectives and has had its potential impacts fully explored and understood.

The Senate's institutional design at the time of Confederation reflects both purposes. In a desire to ensure that upper-class interests were given special representation, senators were required to meet a property requirement of four thousand dollars. So that less populous regions and provinces would not be overwhelmed by their larger counterparts, the country was divided into four regions of 24 senators each (with additional seats for Newfoundland and Labrador and the territories, as relative latecomers to Confederation). Senators were appointed for life and, in order to enhance the Senate's function as a chamber of legislative review, senators were appointed on the advice of the prime minister rather than elected.Footnote 1 These two design elements would theoretically allow senators to act in the broader interests of the country, rather than according to the momentary wishes of a particular electorate. Senators were therefore meant to be independent of electoral concerns and, while partisan from the very beginning, a step removed from partisan electoral processes.

Their lack of elected status was also explicitly meant to undermine senators’ ability to cause legislative deadlock. Speaking in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1865, George Brown (as quoted in Ajzenstat et al., Reference Ajzenstat, Romney, Gentles and Gairdner2003: 85) worried that a Parliament with two elected chambers would be invariably deadlocked, particularly if different parties held majorities in the two chambers: “They might amend our money bills, they might throw out all our bills if they liked, and bring a stop to the whole machinery of government. And what could be done to prevent them?”

By ensuring that senators lacked the popular legitimacy conferred by election, Brown hoped that they would responsibly review and revise legislation from the elected chamber but not unduly delay or obstruct the government. John A. Macdonald (as quoted in Reid and Scott, Reference Reid and Scott2018: 37) concurred, arguing that “there is an infinitely greater chance of a deadlock between the two branches of the legislature, should the elective principle be adopted, than with a nominated chamber—chosen by the Crown, and having no mission from the people.”

Almost since its creation, the Senate has been a deeply controversial institution. In the past few decades, at least three main charges have led the accusations levelled against this chamber: that it is no longer even roughly reflective of the regional populations of the country; that it is unelected and therefore illegitimate from a democratic perspective; and that it is far too partisan, with senators for the most part appointed on the basis of partisanship and pliable to the direction of their party leaders, despite the founders’ intent that the body be relatively independent.

These criticisms have a serious effect on the Senate's ability to exercise its substantial formal powers. Whenever senators have chosen to obstruct legislation emanating from the House of Commons, they have faced accusations of democratic illegitimacy for defying the will of the elected House of Commons (Smith, Reference Smith2003: 3–4). Consequently, Canadian senators have largely avoided direct confrontation with the House of Commons, particularly in the years leading up to the Trudeau Senate reforms (Smith, Reference Smith2003: 4).

Despite repeated attempts, constitutional reform proposals meant to make the Senate more democratic, independent, accountable and representative of shifting population trends have universally failed. Docherty (Reference Docherty2002) argues that this is because these reforms have been bundled into wider constitutional reform packages that have then failed under the weight of their internal inconsistencies. Writing in the decade after the failure of the Charlottetown Accord, Docherty (Reference Docherty2002), Smith (Reference Smith2003), Russell (Reference Russell2004) and others argued that the only way to enact meaningful Senate reform would be to avoid formal constitutional amendments, aside from those that could be unilaterally enacted by the federal government. The Conservative government of Stephen Harper attempted to pass a program of reform that would have introduced consultative elections for vacant Senate seats and reduced the term of office to nine years, but it was abandoned after the Supreme Court ruled in the 2014 Senate reform reference that such reforms would require formal constitutional amendment with provincial consent.

In this decision, the court articulated an understanding of the Senate's fundamental purpose that has a direct bearing on the reforms that were subsequently introduced by the Trudeau government. O'Brien (Reference O'Brien2019) argues that the court's ruling ignored several historical models of Canadian bicameralism and instead focused on one narrow understanding of the Senate's role: as a complementary and independent chamber of sober second thought. In the process, the court acknowledged but downplayed the Senate's role in providing regional representation (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2019: 541).

This ruling had a significant impact on the reform agenda that was implemented by the newly elected Trudeau government in 2015. Instead of addressing concerns related to regional representation or the potential democratic illegitimacy of an unelected chamber, the Trudeau reforms were aimed primarily at increasing the Senate's independence and removing partisanship from the chamber. To this end, the Independent Advisory Board (IAB) was created through an order-in-council to independently evaluate applicants for Senate vacancies and shortlist them based on the following criteria: nonpartisanship, a commitment to increased diversity in the Senate (specifically, increasing Indigenous, female, and racialized minority representation), knowledge of the legislative process and a record of leadership in public life (IAB, 2016). The next step in the process is for the prime minister to choose from the shortlist when recommending eligible candidates to the governor general for appointment. Senators are appointed and sit as independents. This reformed appointment process both arguably adheres to the strict guidelines for unilateral federal Senate reform set out by the court and addresses the perennial complaint that senators were chosen for their partisan loyalty and acted accordingly once in the Senate.

The two other major changes that have taken place in the Senate align with the principles underlying the IAB. The role of government leader in the Senate, who was traditionally a member of cabinet and the leader of the government caucus, was replaced with that of government representative. The government representative still bears many of the same responsibilities as the government leader: most especially, ensuring that the government's legislative agenda is passed through the Senate by collaborating with both cabinet and senators. However, the government representative no longer leads any government caucus, aside from a team of two other senators who assist with the passage of legislation. This group of senators is known as the Government Representative Office (GRO). The decision to reform the office into the GRO, like the creation of the IAB, was taken by the Liberal government.

The final major change, the creation of several nonpartisan caucuses, has been driven by senators in reaction to the aforementioned changes. The creation of nonpartisan caucuses was precipitated by the 2014 expulsion of Liberal senators from the national Liberal caucus (although many of these senators went on to form the now-defunct SLC, which lacked formal links to the party). The independent senators appointed by Justin Trudeau were appointed expressly on the condition that they avoid any partisan affiliation in the Senate. Since many of the rules of the Senate, including the allocation of speaking time, committee seats and even offices, are dependent on being a member of a caucus, these newly appointed independents joined with other independent senators to form the Independent Senators Group. The ISG, along with the SLC and the Conservative caucus (the latter of which maintained its place in the Conservative national caucus), were the three official caucuses present in the 42nd Parliament.

Comparative bicameral examples suggest that these reforms have the potential to make the Senate a more powerful legislative chamber if they are implemented properly. Controversy over the proper extent to which an upper chamber should exercise its powers is an almost universal aspect of bicameralism: these chambers are designed to check the will of directly elected lower houses, which makes them, as Russell (Reference Russell2013a: 8) puts it, “fundamentally controversial.” Lijphart (Reference Lijphart2012: 192–94) argues that the strength of upper chambers is dependent on three factors: their formal powers, their congruence or incongruence with the lower chamber and their method of selection.

Formal powers are a relatively straightforward factor affecting upper chamber strength. Many constitutions limit the powers of the upper chamber when compared to the lower chamber, often by reducing the areas in which they can legislate or limiting their veto so that it is suspensive rather than absolute. The Canadian Senate, which Lijphart (Reference Lijphart2012) ranks highly in terms of formal powers, nevertheless is not a confidence chamber, cannot originate any legislation that increases taxes and has only a suspensive veto over constitutional amendments.

The second factor, congruence, reflects the fact that many upper chambers are specifically tasked with representing political minorities. A bicameral parliament has incongruent chambers when the upper chamber's basis of representation is different than that of the lower chamber. Perhaps the most common examples of incongruent legislatures are federal legislatures in which the lower chamber is constituted on the basis of population while seats in the upper chamber are apportioned on the basis of federal subnational units (Russell, Reference Russell2001). However, parliaments can also be incongruent because of numerous other factors, including class, religion or party. Indeed, as Tsebelis (Reference Tsebelis2002) demonstrates, partisan incongruence is the most reliable predictor of inter-chamber conflict and subsequently of upper chamber strength.

The third factor that Lijphart indicates is the method of selection. His straightforward conclusion is that when an upper chamber is elected, it has the “democratic legitimacy” to challenge the lower house (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012: 193). Conversely, and as is often the case, when upper chambers are appointed or indirectly elected, they lack this legitimacy and therefore will be less likely to exercise their formal powers.

This explanation is expanded by Russell (Reference Russell2013b) in her analysis of the 1999 reforms to the British House of Lords. She finds that the change from a largely hereditary House of Lords to one where the overwhelming majority of peers were appointed for life, unable to pass on their seats to their children, resulted in a House of Lords that was far more willing to use its constitutional powers.

Lijphart's (Reference Lijphart2012) theorization of bicameral strength cannot account for this increase in the Lords’ effective power. The formal powers of the Lords remained unchanged, and its members lacked the legitimation afforded by election. Yet, as Russell demonstrates, members of the reformed House of Lords had increased legitimacy, or “social support.” She draws on a three-part understanding of legitimacy to demonstrate how the reforms had led to the increase of the Lords’ power: through increased input, throughput and output legitimacy.

Input legitimacy refers to legitimacy gained through the creation or composition of an institution. This can most clearly be achieved through election, which provides a popular mandate, but also by having a more independent and descriptively representative chamber. Throughput legitimacy refers to legitimacy gained from the procedures of an institution: by having a less partisan and “fairer” process of deliberation or operation. Finally, output legitimacy refers to the social support gained by an institution's output: for instance, by making policy decisions that find popular appeal even if they are in opposition to an elected lower chamber. These measures, as Russell (Reference Russell2013b) demonstrates, were all present in the reformed House of Lords and all contributed to its increased strength after 1999.

These measures of legitimacy are also relevant to the reformed Canadian Senate. The reforms address neither the formal composition of the Senate nor its formal method of selection. Instead, the reforms seek to increase the input legitimacy of the Senate by having an independent body, the IAB, recommend nonpartisan applicants for appointment to the Senate and by ensuring that these new senators are more descriptively representative of the country than the Senate has previously been. The reform most clearly reflecting throughput legitimacy is the removal of a partisan Liberal caucus and the creation of independent caucuses, of which the largest and most prominent is the ISG. Finally, the output legitimacy of the Senate is to be strengthened by having a more active Senate judicially exercising its substantial powers to contest the will of the government and the elected House of Commons when necessary.

The preceding discussion lends itself to a more complete understanding of the Trudeau reforms and to a series of measurable questions about how they have shaped the Senate. The first of these relates to the degree to which independence in the reformed Senate has increased. The Trudeau Senate reforms address the criticism that senators have been appointed based on partisanship and out of an expectation that senators would support the legislative agenda of the prime minister and party that supported their appointments. To this end, the independence of senators should be measured as an end in and of itself. However, as Russell (Reference Russell2013b) demonstrates, increased independence can lead to increased legitimacy and subsequently increased upper chamber legislative strength. Thus, we test the independence of the Senate both to determine if the Trudeau Senate reforms have succeeded on this front and so that we can see how changing independence affects bicameral strength.

On a similar theme, ideological diversity is also an important measure of the reform's success. Again, one of the main reasons for this is that the Trudeau government itself committed to the appointment of “a diverse slate of individuals, with a variety of backgrounds, skills, knowledge and experience” (IAB, 2016). It also reflects the fact that one of the primary criticisms levelled against the reformed appointment process is that it leads to the appointment of senators who are ideologically aligned with the Liberal government, even if they are not partisan Liberals. Finally, demonstrated ideological diversity would align with increased input and throughput legitimacy and therefore could also be expected to increase the Senate's relative strength. These questions lead directly to a third question: Have the reforms made senators more willing to use their formal powers?

3. Data and Methods

The analysis of recorded divisions, or legislative votes, is one of the primary established methods of analyzing the political behaviour of parliamentarians (Diermeier et al., Reference Diermeier, Godbout, Yu and Kaufmann2012; Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal1985, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007). It is not, however, a method without its challenges, the most significant of which is the selection bias of recorded divisions (Hug, Reference Hug2010). Of the thousands of divisions that take place in the Senate over a session of Parliament, for instance, only a few hundred at most are recorded in detail. Senate rules dictate that a recorded division takes place when two senators stand to request it. In practice, this means that most votes are never recorded. Our dataset, for instance, shows that only 197 divisions were recorded over the four-year duration of the 42nd Parliament.

Comparative studies of roll call voting have established that the decision to call for a recorded division is a strategic one (Carrubba et al., Reference Carrubba, Gabel, Murrah, Clough, Montgomery and Schambach2006; Hug, Reference Hug2010). Recorded divisions may be requested in order to instil discipline in the ranks of a party by forcing backbench legislators to publicly declare their loyalty, or else to highlight the disunity in an opposing party's ranks. They might be called to highlight differences between political groupings within a legislature and have also been used simply to delay the passage of legislation when a party lacks a majority in the legislature (Dewan and Spirling, Reference Dewan and Spirling2011). Although previous studies of roll call voting have largely dealt with elected chambers, interviews with senators suggest that recorded votes are being called to highlight differences within and among the various caucuses, which suggests that strategic reasons continue to inform the decision to call for a recorded division.

Study of voting behaviour in the Senate is further complicated by its role as an unelected secondary chamber. Senators have historically proven reticent to exercise their formal powers and vote down government legislation that has passed the House of Commons, in order to avoid being charged with democratic illegitimacy. The doctrine of complementarity as outlined by then-Government Representative Peter Harder (Harder, Reference Harder2018) suggests that senators should refrain from voting down legislation that was passed by the House unless there is a compelling democratic argument for doing so, an argument that finds support in the 2014 Senate reform reference (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2019). Factors such as this which lead to strategic voting mean that any analysis of recorded division will inevitably reflect a combination of sincere preferences and strategic decisions on the part of senators.

This complicates roll call vote analysis, as a vote that supports the government position on a given issue could be interpreted as either ideological affinity with and loyalty to the government or an acknowledgement of the Senate's complementary role. The clearest proof of IAB-appointed senators’ independence and ideological diversity will therefore only be evident once a different government takes office and enacts a different legislative agenda. Thomas (Reference Thomas2019: 27) discounts the usefulness of quantitative analysis of roll call votes almost entirely, arguing that such analyses are unable to account for the content and relative importance of each vote, instead treating each observation as an equally valid indication of a senator's ideology or loyalty. He argues that a more fruitful avenue of research would instead be “to move beyond counting aggregate votes on bills to identify what was at stake in the various votes and to gather qualitative evidence on the less public dimensions of the parliamentary process” (25).

There are indeed limits to the claims that can be made through quantitative analysis of roll call votes, just as there are limits to the claims that can be made through qualitative analysis. In this study, our interest lies in the aggregate behaviour of senators, which means we must accept a certain reduction in the amount of nuance in our analysis. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of voting behaviour should complement one another, and in future studies we hope to do just that.

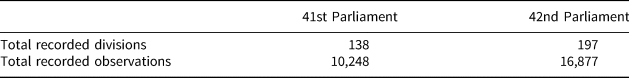

The primary dataset that we analyze in this study contains every recorded division in the 41st and 42nd Parliaments. In the 41st Parliament (2011–2015), the Conservative party held a majority in both chambers of Parliament, while in the 42nd Parliament, the Liberals held a majority in the House of Commons and the Conservatives held a plurality in the Senate until 2017. The recorded votes in this dataset represent only a subset of the total divisions that occurred in the Senate over this period, but most of these votes were relatively uncontroversial and therefore unrecorded voice votes. Although the total number of Senate votes that took place during the 41st and 42nd Parliaments is not recorded, the Senate Hansard shows that the formulaic language calling for a vote (“Is it your pleasure, honourable senators, to adopt the motion?”) was used 1,360 times during the 41st Parliament and 1,269 times during the 42nd Parliament. The total number of recorded divisions and the total number of observations (referring to each individual recorded vote) are contained in Table 1, which suggests that only about 10 to 15 per cent of Senate divisions were recorded.

Table 1. Recorded Senate Votes in the 41st and 42nd Parliaments (2011–2019)*

*Data collected from Library of Parliament (2019a) and the Senate Hansard.

We refer to our first measure as loyalty scores, following Godbout and Høyland (Reference Godbout and Høyland2013) and Godbout and Høyland (Reference Godbout and Høyland2017). These loyalty scores track how often a given senator votes alongside the position of the government leader/representative in the Senate. Prior to the Trudeau reforms, the government leader was both a member of cabinet and the leader of the government caucus in the Senate. Per the principle of cabinet collective responsibility and the government leader's specific legislative role in the Senate, we take their vote as reflective of the government position. The government leaders in the 41st Parliament were Marjory LeBreton and Claude Carignan. The government representative throughout the 42nd Parliament, Peter Harder, did not lead a government caucus, but he still frequently attended cabinet, was tasked with passing the government's agenda through the Senate and has confirmed that his position on a given vote can be taken as the government's position (interview with Harder, December 4, 2019).Footnote 2 We develop these loyalty scores for both the 41st and 42nd Parliaments so that we can compare changing loyalty levels among the various caucuses before and after the reforms were implemented. Senators with less than five recorded votes are excluded from the analysis.

The second measure we use are W-NOMINATE scores. W-NOMINATE scores were developed by Poole and Rosenthal (Reference Poole and Rosenthal1985) for analysis of voting patterns in the US Congress (Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007). They plot the ideal point of a legislator, based on their voting record, in low (usually two) ideological dimensional space, using the spatial theory of voting. The application of W-NOMINATE scores to the US Congress has demonstrated that legislators are divided on a primary economic left-right x-axis and then again on a secondary y-axis related to issues of race and culture (Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007). While the strict party discipline and conventions of cabinet confidence of Westminster parliaments generally make scaling techniques such as W-NOMINATE unsuitable for vote analysis (Spirling and McLean, Reference Spirling and McLean2007), the reformed Senate lacks both features. W-NOMINATE scores should therefore provide a valuable insight into the clustering of senators as seen through voting behaviour. The remaining data are primarily drawn from LEGISinfo and Parlinfo, two databases maintained by the Library of Parliament. These contain a wealth of detailed historical information on legislation, including sponsors and the legislations’ ultimate fate. These provide a strong measure of the Senate's relative strength, particularly when it comes to its record of passing, delaying and vetoing legislation.

4. Loyalty Scores

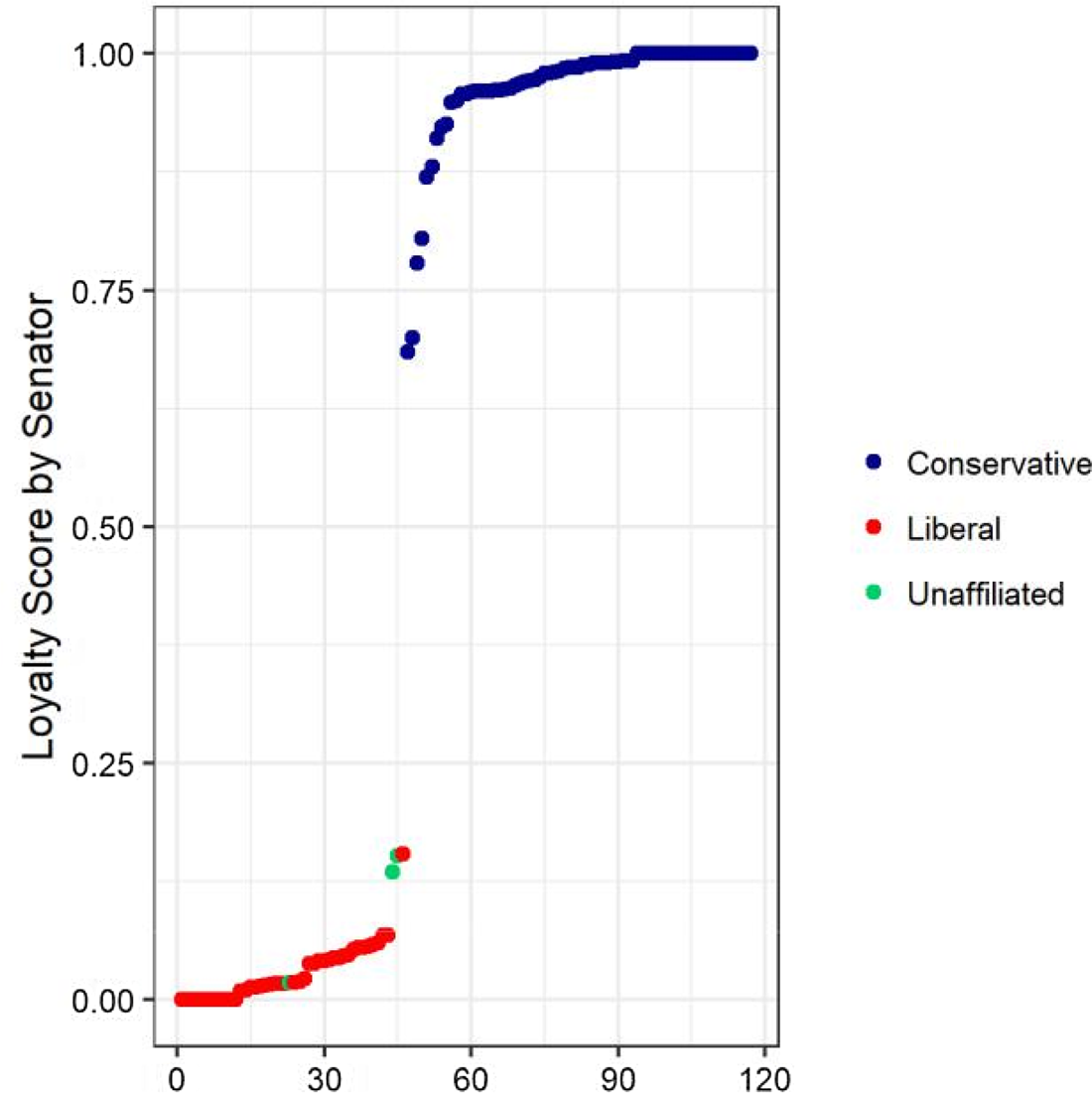

The complete Senate loyalty scores of the 41st and 42nd Parliaments are shown as scatterplots in Figures 1 and 2. Each dot represents a given senator, situated on the y-axis based on how often they voted alongside the government position throughout the life of the Parliament. The number of votes per senator varies. The results displayed in Figure 1 demonstrate significant levels of partisan polarity within the Senate in the 41st Parliament, prior to the introduction of the Trudeau reforms. As Table 2 shows, the mean loyalty score of Conservative senators was over 96 per cent, while the mean loyalty score of Liberal senators toward government positions was less than 3 per cent. This level of polarity is comparable to the House of Commons over the same period, although the outliers in the Senate are more widely distributed than those in the House (Godbout and Høyland, Reference Godbout and Høyland2017).

Figure 1. Senate Loyalty Scores in the 41st Parliament (2011–2015)

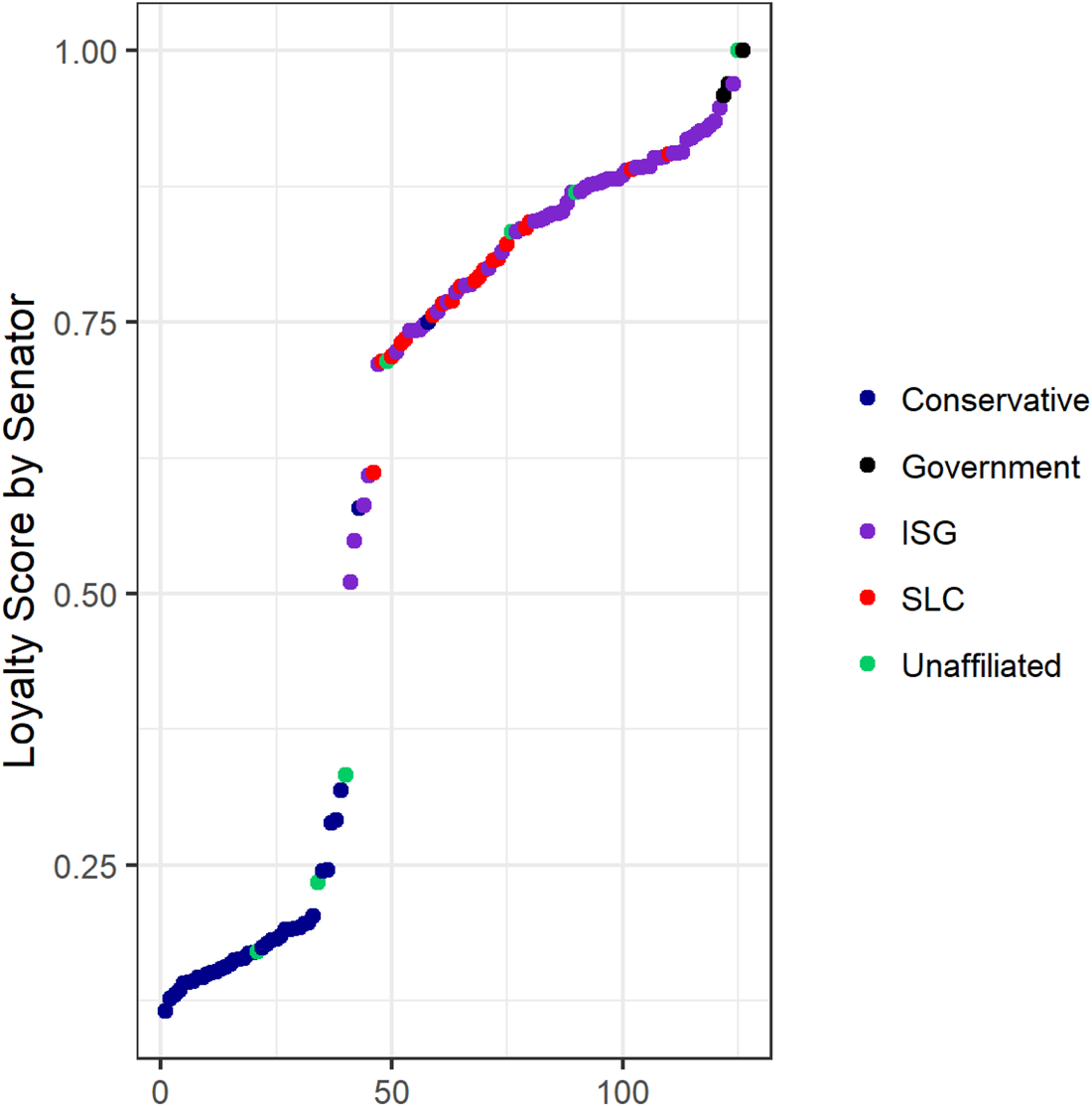

Figure 2. Senate Loyalty Scores in the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019)

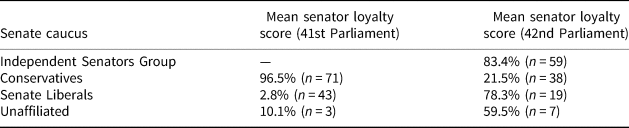

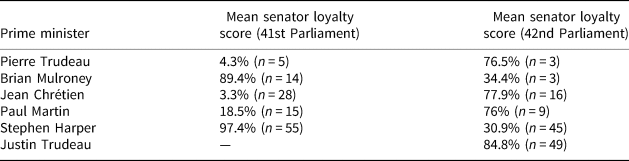

Table 2. Mean Senator Loyalty Scores in the 41st and 42nd Parliaments (by caucus)*

*N = the number of senators in the caucus over the course of the Parliament.

Unlike the preceding Parliament, the 42nd Parliament had neither a government caucus nor a whipped Liberal caucus. Figure 2 shows how these changes, alongside the introduction of numerous independent senators appointed through the IAB process, impacted senatorial loyalty to the government position. We can see that in every caucus—the ISG, the Senate Liberals and the Conservatives—there is significantly less uniformity in voting than in the 41st Parliament. The mean loyalty score of the Conservative opposition was 21.5 per cent, a significant increase from the Liberal opposition (at 2.8 per cent) in the previous Parliament. This suggests that Conservative senators, although clearly opposed to the Liberal government's position overall, have nevertheless become less cohesive as a bloc and are less instinctively opposed to the government's position than previous oppositions.

The most significant support for the Liberal government's position came from the ISG, which has a mean loyalty score of 83.4 per cent. This is higher even than the SLC senators (78.3 per cent), almost all of whom were appointed as Liberal senators by former Liberal prime ministers. Nevertheless, both caucuses exhibit significantly less uniform support for the government's position than, for instance, the Conservative caucus during the 41st Parliament. Instead, we can see that while there are relatively clearly defined groups supporting (the ISG and the SLC) and opposing (the Conservatives) the Liberal government's position, the overall impact of the reforms appears to have been to reduce partisan polarity on all sides of the Senate.

Nevertheless, the ISG is notable in that its members usually vote together and in support of the government position. Their uniformity is like that of the Conservatives, albeit in support of the government rather than in opposition to it. This becomes even more apparent when looking only at those senators appointed under the IAB process, as shown in Table 3. In this table, mean loyalty scores are calculated for senators grouped together by the prime minister who appointed them. This circumvents the complications caused by senators switching caucus affiliations in the middle of a parliamentary session and allows us to isolate those senators who were appointed under the IAB process—that is to say, those senators who were appointed by Justin Trudeau. The broader story is again one of reduced polarity within the Senate and less cohesion within each of these groups. Notably, senators appointed on the advice of Justin Trudeau were the most likely to support the Trudeau government's position at a rate of 84.8 per cent.

Table 3. Mean Senator Loyalty Scores in the 41st and 42nd Parliaments (by prime minister)

This analysis, therefore, has three major findings. The first is that in the 42nd Parliament, senators from all parties and caucuses displayed less loyalty to a partisan position than in the 41st Parliament. This is true even of the Conservative senators, even though their internal parliamentary organization was virtually unchanged. The second finding is that the ISG, more even than the SLC, is the most consistent supporter of the government position, undermining their ability to claim to represent a broad swath of ideological and political diversity in Parliament. Finally, despite the loosening of partisan voting patterns in the Senate, the record of the 42nd Parliament suggests that caucus membership remains a powerful predictor of voting patterns.

5. W-NOMINATE Scores

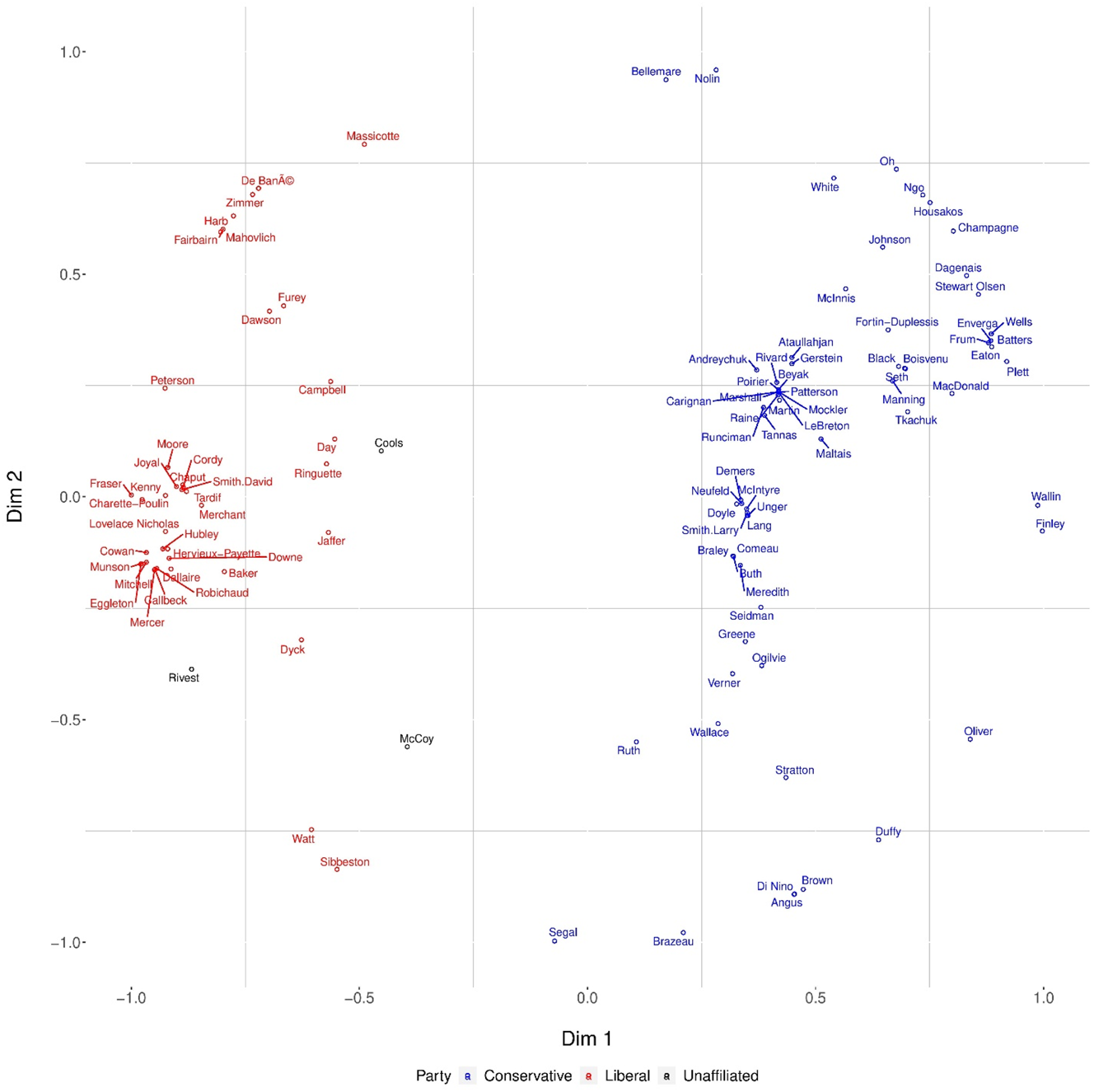

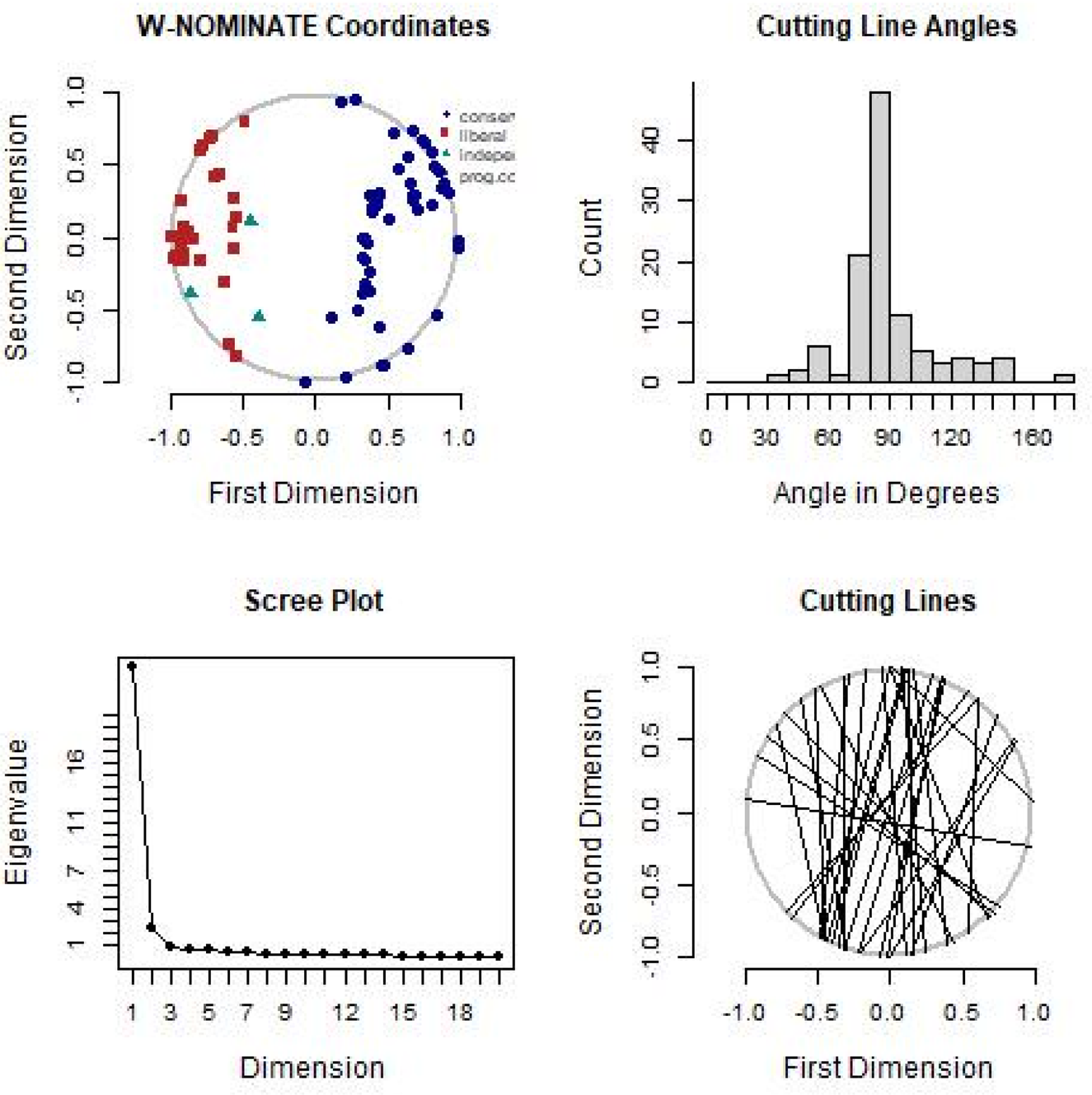

Figure 3 summarizes the W-NOMINATE scores of Canadian senators in the 41st Parliament (2011–2015), while Figure 4 does the same for senators in the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019). The positions of senators on the top two dimensions of disagreement are plotted in both figures.

Figure 3. Senate W-NOMINATE Scores in the 41st Parliament (2011–2015)

Figure 4. Senate W-NOMINATE Scores in the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019)

In Figure 3, senators are divided along a primary dimension, arranged along the horizontal axis, with Conservatives on the right and Liberals on the left. The first dimension, as the scree plot in Figure A.1 in the supplementary material shows, accounts for by far the largest amount of variation among the senators. This leads us to conclude that this dimension can best be described as a partisan dimension.

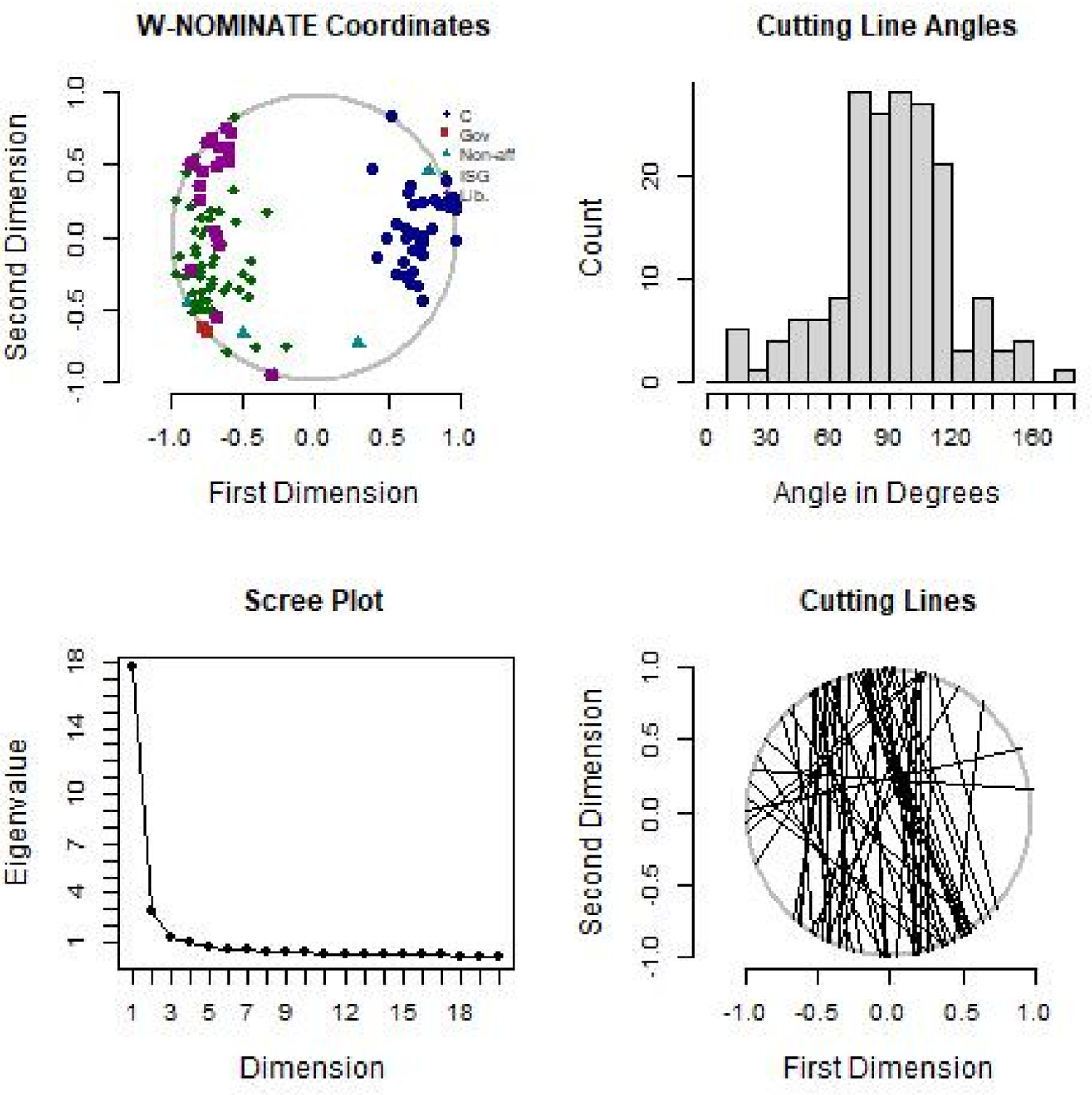

In Figure 4, which plots senators based on their votes in the 42nd Parliament, there is also a primary dimension, arranged along the horizontal axis, which polarizes Conservative senators, this time against both Liberal and ISG senators. In other words, there appears to be a “Conservatives-against-the-rest” dynamic, but there is no evidence here that the ISG senators are significantly different than the Liberal senators. Again, the scree plot contained in Figure A.2 shows that this first dimension accounts for by far the most variation among the senators.

Thus, while we find no evidence that the ISG senators behave differently than the Liberals, we also find little evidence that ISG senators are voting less cohesively than are senators affiliated with political parties. As with the other scaling analyses, there are some disadvantages of using NOMINATE scores to estimate ideal points in a legislature where party discipline is high (Spirling and McLean, Reference Spirling and McLean2007). We can assume with confidence that ISG and SLC senators are not whipped during legislative votes, but this may not be the case with Conservative senators who are still members of their party's caucus. Hence, the polarization we find between, on the one hand, the Conservative senators and, on the other, the ISG, Liberal and GRO senators is not surprising. It corresponds to the government-versus-opposition dynamic of legislative voting observed in most parliamentary systems where party discipline is high, as opposed to a left/right ideological opposition between legislators that is more generally found in presidential systems (Godbout and Høyland, Reference Godbout and Høyland2011). Our results also indicate that a handful of votes load heavily on the second dimension of voting, cutting across caucus divides. These were related to assisted dying and criminal code reform, two controversial issues that were government priorities and were passed early in the course of the Parliament.

The relative positioning of several senators in Figure 4 support the hypothesis that both ideology and party discipline are at play here. Senator David Adams Richards, plotted in the figure as “Richards,” was appointed by Prime Minister Trudeau as an independent but was only briefly a member of the ISG before leaving to sit as an unaffiliated senator due to his concerns that the ISG was too willing to act in support of the Liberal government's agenda. His relative position in Figure 4, near to the centre but also closer to the Conservative caucus than to most SLC or ISG senators, suggests that ideology is a factor at play in shaping votes.

Similarly, the Conservative outliers among the W-NOMINATE scores bolster our belief that party discipline remains a powerful predictor of voting behaviour in the Senate. Senator Greene, the most notable outlier, was expelled from the Conservative caucus in the spring of 2017, and therefore most of his recorded votes are from a period when he was not subject to party discipline. Unsurprisingly, he sits in the very middle of the first dimension. Other caucus outliers, such as Senator Merchant, left the Senate early in the session and therefore have relatively few observations recorded in our dataset.

6. The Senate's Legislative Record in the 42nd Parliament

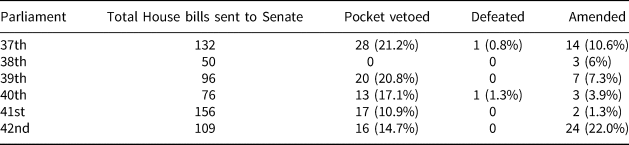

In this section, we review the Senate's record as related to the passage of legislation, a relatively straightforward indicator of bicameral strength. The data are summarized in Table 4, which presents the legislative record in historical perspective. The data shown here arguably reflect a complementary understanding of the Senate's legislative role. It shows every bill that originated in and passed the House of Commons between 2001 and 2019 and that was subsequently sent on to be reviewed by the Senate. The number of pocket vetoes and defeats of government legislation are not extraordinary: indeed, not a single bill was defeated outright. Although the Senate did not live up to Peter Harder's (Reference Harder2018: 5) hope that it would “act in accordance with the principle that every bill is deserving of a democratic vote,” the sixteen pocket vetoed bills are similar in number to that of previous Parliaments. Nevertheless, it should be noted that major pieces of legislation that were passed with significant support from the House of Commons were fatally delayed, in some cases deliberately, to the point that senators could avoid directly voting down these bills. Yet neither the rate of pocket vetoes nor defeats in the Senate are out of line with past practice.

Table 4, House of Commons Legislation in the Senate, 2001–2019*

Instead, the most notable change is the increased level of amendments. Here, the Senate clearly exercised its constitutional prerogatives to a much higher degree than in previous Parliaments. Under the Martin and Harper governments (the 38th–41st Parliaments), the rate of Senate amendments had slipped into the mid to low single digits. In the 42nd Parliament, conversely, the Senate amended fully one-fifth of the House bills that came before it, a rate that exceeded that of any other Parliament for the last century. A closer examination of these amendments shows that in the case of nine bills, the House of Commons fully accepted the Senate's amendments and immediately passed the amended bills into law. Fourteen of these amended bills, including major government priorities such as cannabis legalization and the regulation of assisted dying, had some or all of the Senate's amendments removed by the House of Commons, after which the Senate did not insist on their amendments (Library of Parliament 2019a).

The overall record, therefore, suggests that the Senate was more willing to exercise its powers in the wake of the Trudeau reforms. Nevertheless, it is clearly not a Senate gone wild: Senators almost always ended up immediately accepting the House of Commons’ decision, and in a number of cases the House of Commons clearly felt the Senate's amendments had improved legislation, as it allowed the amendments to remain.

7. Conclusion

Three questions drove this analysis: First, are senators appointed under the IAB demonstrating independence; second, do these senators show evidence of ideological diversity; and finally, are senators more willing to use their formal powers?

On the first question, we found mixed evidence of senatorial independence. While senators from all parties are demonstrating less adherence to a strict party line, ISG senators appointed by Justin Trudeau are the most likely to support his government's agenda. This evidence cannot be dismissed as simply adherence to a complementary understanding of the Senate's role: as discussed above, the legislative agenda of the 42nd Parliament provided plenty of opportunities for senators to demonstrate independence while still respecting the primacy of the elected House of Commons. Nevertheless, the clear partisanship of pre-reform Senate appointments is at the very least reduced.

The W-NOMINATE scores tell a similar story. The most obvious dynamic is one of the Conservative opposition against the rest. However, the fact that these non-Conservative senators are predominantly either from the ISG or the SLC suggests that there is a notable lack of ideological diversity, insofar as that can be gleaned from voting records, among the senators appointed under the IAB. Both measures suggest that partisan incongruence, as Tsebelis and Money (Reference Tsebelis and Money1997) argue, remains the most important predictor of contestation between chambers in a bicameral legislature.

The vote analyses therefore offer mixed evidence for increased independence and ideological diversity. Certainly, the superficial aspects of the reforms—the removal of senators from the national Liberal caucus, the appointment of senators under the IAB and the lack of nominal partisanship among these new senators—suggest a more independent Senate, but there is also substantial evidence that the ISG was a reliable supporter of the government throughout the 42nd Parliament. Nevertheless, the formal links between the Liberal government and the Senate have been largely severed.

If independence and ideological diversity are, as we argue, crucial to increasing the legitimacy and subsequently the strength of the Senate, then the Senate's legislative record reflects the mixed verdict given above. The Senate is more active than it has been at least for the past two decades. Its actions, moreover, are largely in line with the doctrine of complementarity laid out by Peter Harder: it is amending and introducing legislation at notably higher rates than in previous Parliaments. This adds credence to Russell's (Reference Russell2013b) argument: increased legitimacy can lead to increased bicameral strength, even without the introduction of elections to an upper chamber. However, it is important to stress the fundamental limitations that face an unelected chamber. The concept of complementarity, which encourages senators to actively participate in the legislative process, is nevertheless predicated on the belief that the elected House should have the ultimate say.

The implications of these findings for the long-term success or failure of the reforms are mixed. On the one hand, their deliberately limited scope has allowed the government to implement the reforms unilaterally, and the Liberal government's re-election in 2019 means that senators will continue to be appointed under the new system for the foreseeable future. Whether future governments are willing to continue with these reforms or go back to the unreformed process of partisan appointment may well depend on how successful senators are at portraying themselves as truly independent. The evidence for this independence is mixed at best, but a change in government will likely prove to be the real test.

Nevertheless, the reformed Senate retains many of the features that have excited fervent opposition throughout its history. While the partisanship of the appointment process and of the internal workings of the Senate has been reduced, its deficiencies as a chamber of regional representation remain, as does the fact that it is unelected. It certainly does not address most of the criticisms that campaigners for a Triple-E Senate have levelled at it. As then British Columbia premier Christy Clark put it:

The process doesn't make the Senate any better. I would argue that it actually makes it worse because the Senate is completely unrepresentative of the provinces. … The Senate doesn't work now. The only other thing that could make the Senate worse would be having all of these unaccountable, unelected patronage appointments starting to think that they are somehow legitimate and have the power to make decisions on behalf of our country. They don't. They shouldn't. … And we won't endorse it. (Canadian Press, 2015)

Yet these reforms are the most significant made to the Senate over its 150 years of existence. They entrench, as O'Brien (Reference O'Brien2019) argues, a distinct vision of the Senate's role: above all else, a “complementary legislative body of sober second thought.” Whether this role is enough to justify the Senate's continued existence in its current form will no doubt depend on the demonstrated independence and earned legitimacy of the senators themselves.

Appendix

Figure A.1. W-NOMINATE Scores, 41st Parliament

Figure A.2. W-NOMINATE scores, 42nd Parliament