Introduction

In an article, ‘The Slaves were Happy’: High School Latin and the Horrors of Classical Studies, Erik Robinson, a Latin teacher from a public high school in Texas, criticises how, in his experience, Classics teaching tends to avoid in-depth discussions on issues such as the brutality of war, the treatment of women and the experience of slaves (Robinson, 2017). However, texts such as the article ‘Teaching Sensitive Topics in the Secondary Classics Classroom’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016), and the book ‘From abortion to pederasty: addressing difficult topics in the Classics classroom’ (Sorkin Rabinowitz & McHardy, Reference Rabinowitz N and McHardy2014) strongly advocate for teachers to address these difficult and sensitive topics. They argue that the historical distance between us and Greco-Roman culture and history can allow students to engage and participate in discussions that may otherwise be difficult and can provide a valuable opportunity to address uncomfortable topics in the classroom. Thus, Robinson's assertion that Classics teaching avoids these sensitive topics may not be so definitive. Regardless, Robinson claims that honest confrontations in the classroom with the ‘legacy of horror and abuse’ from the ancient world can be significantly complicated by many introductory textbooks used in Latin classes, such as the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC), one of the most widely used high school Latin textbooks in use in both America and the United Kingdom (Robinson, 2017). In particular, Robinson views the presentation of slavery within the CLC as ‘rather jocular and trivialising’ which can then hinder a reader's perspective on the realities of the violent and abusive nature of the Roman slave trade (Robinson, 2017). As far as he was concerned, the problem lay with the characterisation of the CLC's slave characters Grumio and Clemens, who, he argued, were presented there as happy beings and seemingly unfazed by their positions as slaves. There was never any hint in the book that Grumio or Clemens were unhappy with their lives or their positions as slaves, even though, as the CLC itself states in its English background section on Roman slavery, Roman law ‘did not regard slaves as human beings, but as things that could be bought or sold, treated well or badly, according to the whim of their master’ (CLC I, 1998, p. 78). One might argue, therefore, that there seems to be a disconnect between the English language information we learn about the brutality of the Roman slave trade provided in the background section of Stage 6, and what we can infer about Roman slavery from the Latin language stories involving our two ‘happy’ slaves.

The CLC has been criticised already on its presentation of women and gender bias, with the criticism that ancient women are not responsibly portrayed or represented through the stories used in the textbooks as they unconsciously reinforce negative modern social norms in students (Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013, p. 28). The gender inequality witnessed in the Classics textbooks is perhaps reflective of gender inequality in the Classics discipline as argued by Churchill in her work ‘Is there a Woman in this Textbook?’ (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p. 86). Churchill claims that Latin teaching is still perceived as an elitist, male discipline and this historical gender bias persists ‘however unintentionally and unconsciously, in contemporary textbooks, readers and methods of teaching Latin’ (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.88). Churchill criticises how the Classics discipline has been slow to address these issues of gender bias in textbooks even as classroom demographics have changed to be ‘more representative of the population as a whole than they were fifty, even twenty-five, years ago’ (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.87). The most current edition of the CLC, used predominantly in the US, has addressed these criticisms to an extent by introducing a daughter and sister to Caecilius’ family.

The CLC has further been criticised for its lack of inclusivity and people of colour, and for its positive depictions of imperialism (Bracey, Reference Bracey2017). This criticism was recently recognised by the Cambridge Schools Classics Project in a statement in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. In their statement the CSCP pledged that the new UK/international 5th and all future editions of the Cambridge Latin Course ‘will better represent people of colour and promote critical engagement with matters such as imperialism, slavery and cultural subjugation’ (CSCP, 2020). This research was planned and executed prior to the Black Lives Matter movement in March 2020 and subsequent statement from CSCP and thus played no part in the initial inspiration for this research. However, it is important to note that the CSCP has now recognised an issue with the portrayal of slavery within its textbook, warranting a change in how the topic is addressed in future editions.

Most research to date that addresses the teaching of Roman slavery focuses on teacher's perceptions of approaching the sensitive issue of slavery with some criticism of source materials such as the CLC or Ecce Romani (Robinson, 2017; Bostick, Reference Bostick2018; Dubois, Reference Dubois, Rabinowitz N and McHardy2014). Even though there has been criticism for the presentation of slavery there has not been much research on how this presentation and characterisation of slavery affects, if at all, the students engaging with these texts. Therefore, I decided to conduct my own research into this issue to see how the presentation of slaves in the CLC seemed to affect students’ perceptions of slavery by asking about their opinions of the characters Grumio and Clemens.

My research was conducted in a UK classroom, where attitudes towards slavery and race ‘matters differently’ to the US (Umachandran, Reference Umachandran2019). Dugan in their research ‘The “Happy Slave” Narrative and Classics Pedagogy: A Verbal and Visual Analysis of Beginning Greek and Latin Textbooks’ analyses how current Greek and Latin textbooks used to discuss ancient slavery ‘directly and indirectly engage with the racist language and imagery of 19th-century pro-slavery American literature, propaganda, and performance’ and subsequently helps to propagate racist discourse that permeates the American education system. (Dugan, Reference Dugan2019, p. 62). These ideas are evidently felt by American Latin teachers who recount their struggles in combatting these positive presentations of Greco-Roman enslavement with the horrors and injustice of the transatlantic slave trade, the latter taught extensively in the American classroom (Robinson, 2017; Bostick Reference Bostick2018). In the UK, it is compulsory for secondary schools to address the history of UK colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade which is heralded as ‘one of the most widely taught topics in secondary schools’ history curricula’ (Mohamud et al. Reference Mohamud, Whitburn, Draper and Donington2019). However, generally the UK does not engage as heavily in discourses on racism compared to the US, despite racism being a prevalent issue in British society. The inherent problem lies in the way the UK's issues with structural racism are overlooked in comparison to the US. Eddo-Lodge writes in ‘Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People About Race’;

‘While the black British story is starved of oxygen, the US struggle against racism is globalised into the story of the struggle against racism that we should look to for inspiration — eclipsing the black British story so much that we convince ourselves that Britain never had a problem with race.’ (Eddo-lodge, 2014, pp.54–55)

As Umachandran notes in her piece ‘More than a Common Tongue: Dividing Race and Classics across the Atlantic’, race is ‘not explicitly part of the cultural atmosphere in the UK’ in the same way that it is in the US, but that does not mean that racism does not exist in the UK (Umchandran, Reference Umachandran2019). We cannot simply take American ‘templates’ and ‘formulations’ of race and use them to describe and deconstruct British racism. Instead of using American terminology, Umachandran advocates for the UK to develop ‘more culturally and historically specific ways of doing critical self-reflection around race, class, and empire’ (Umachandran, Reference Umachandran2019). Therefore, it is important to approach the topic of teaching slavery in the UK classroom, not just with American issues surrounding slavery and modern-day racism in mind, but also Britain's role in the transatlantic slave trade and successful global empire. This ‘happy slave narrative’ carries different issues and connotations in the UK classroom; for example, the positive portrayal of empire makes it difficult to see Rome (and subsequently Britain) as the villain.

I carried out my research at an all-girls’ selective grammar school which teaches Latin as a compulsory subject to all students in Key Stage 3, starting in September of Year 7. Whilst slavery is a concept that is addressed in other Latin coursebooks (such as Suburani, Ecce Romani, The Oxford Latin Course), I have chosen to use the CLC because it is the most popular course used to teach Latin at secondary schools in the UK and is the course followed at my placement school. Due to its commercial success, the CLC is responsible for providing the majority of students in the UK their first and possibly only introduction to the institution of ancient slavery. At my placement school, the Classics department was determined that students were able to explore every story in the textbooks as well the background information, meaning that the students had every opportunity to familiarise themselves with the characters and their storylines. As students had two 50-minute lessons a week dedicated to Latin during Key Stage 3, there was no need to rush the students through the books and focus on the language alone. As a result, the nature of how the Latin course was taught in my placement school allowed for my research to focus on the student perceptions of the slave characters and Roman slavery.

Literature review

Should students think critically in the classroom?

To understand why I feel it is important for students to look at the presentation of slaves within their textbook, I will first introduce and consider some general discussion about the role teachers and education play in getting students to think critically about their subjects and the wider world. Discussion surrounding the role education plays in the promotion of critical thinking beyond the classroom has been highly debated for many years. Critical pedagogy is a teaching approach that advocates for students to question their views of accepting social norms and to think critically about the world around them beyond the boundaries of their curriculum. The critical pedagogic advocate and educator, Ira Shor, defines critical pedagogy as;

Habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional clichés, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal consequences of any action, event, object, process, organization, experience, text, subject matter, policy, mass media, or discourse. (Shor, Reference Shor1992, p. 129).

In the context of my research, Shor's critical pedagogy would advocate thinking deeply about our first impression of Clemens and Grumio and going beyond the surface meaning of their characters within the medium of the textbook to help us then question the root causes behind their apparently jovial characterisation and understand the social context and ideology of slavery within ancient and modern society. Thus, by critically evaluating our learning resources, we are able to develop ideas about social justice and gain a critical consciousness, defined by Freire as ‘the development of the awakening of critical awareness’ (Freire, Reference Freire2002, p. 19). This is understood as an in-depth understanding about the world which can lead to freedom from oppression (Mustakova-Possardt, Reference Mustakova-Possardt2003). Such a teaching approach can be said to have a home in the modern classroom when teachers invite students to question the status quo explicitly ‘in the name of justice, democratic rights and equality’ (Macrine, Reference Macrine S and Macrine S2009, p.119). Thus, it is our role as teachers to encourage students to examine critically the world around them and their own perceptions of it in the name of social justice and the promotion of equality. The presentation of slavery allows the perfect opportunity for students to question their own ideologies as well as the ones presented by their textbooks, to seek a deeper meaning and understanding about the issues and to gain a deeper critical consciousness for themselves.

However, not everyone believes that critical pedagogy has a place within the modern classroom. Some argue that a knowledge-rich curriculum is a better route for the development of students as critical thinkers (Ashman, Reference Ashman2018). One common criticism of critical pedagogy is that the input is dependent on the teachers themselves. Teachers who encourage students to question social norms may do so with their own bias and instead of allowing students to decide for themselves, often reinforce one bias with another – perhaps their own. Therefore, when asking students to think critically in the classroom it is important that the teacher does not have a correct answer in mind when scaffolding a discussion as they may consciously, or subconsciously lead the students to that answer. It is also possible that through such scaffolding teachers could promote simplistic ideology on complex societal issues or even extremist views (Hairston, Reference Hairston1992, p. 186). Consequently, I believe is important to consider current concerns about two main aspects of applying the concept of critical pedagogy within the Classics classroom. Firstly, how do we advance a student's ideas about social justice through Classics teaching without inflicting our own personal bias on the students? Secondly, is the subject matter of Classics by its nature problematic in this regard?

How can Classics advance ideas about social justice?

It is generally agreed that Classics as a discipline has historically been enlisted in arguments to legitimise war, conquest and the concept of imperialism as medieval and early modern empires in the west compared themselves to the image of Rome (Kumar, Reference Kumar2012, p.77; Goff, Reference Goff B2005). A shining example can be seen during Britain's colonial years as the British used classical scholarship and the historical past to establish imperial legitimacy during Britain's Indian Empire from 1780–1890 (Sundari Mantena, Reference Mantena R and Bradley2011; Vasunia, Reference Vasunia2013). Over recent years there has been a steady increase in research combatting this centuries-old elitism entrenched within the subject and it has started to tackle the decolonisation and diversification of Classics (Joffe, Reference Joffe2019, p.1; Turner, Reference Turner2018; Giusti, Reference Giusti2020; Bracey, Reference Bracey2020). Giusti gives a definition for decolonisation based off the Keele University's Manifesto for Decolonising the Curriculum, stating;

“decolonisation must not be equated with ‘integration’ or ‘token inclusion’ of non-white cultures and people in academic curricula. Rather, decolonisation necessitates ‘identifying colonial systems’ and oppressive power structures in order to work ‘to challenge those systems’ and create a ‘paradigm shift from a culture of exclusion and denial to the making of space for other political philosophies and knowledge systems’” (Giusti, Reference Giusti2020; Gokay & Panter Reference Gokay and Panter2018).

The movement of decolonising Classics has truly picked up speed; from student campaigns in universities (Turner, Reference Turner2018), to the deconstruction and reconceptualisation of western culture itself (Appiah 2016), to various discourses examining inherent issues still prevalent within modern classical scholarship, for example the use of marble statues from the ancient world as a platform of white supremacy (Bond, Reference Bond2017). Joffe summarises this movement of self-awareness to the three most basic yet pivotal questions at the heart of classical identity: ‘Who studies Latin and Greek, whom we study in the ancient world when we do so, and to whom this cultural patrimony belongs in the first place.’ (Joffe, Reference Joffe2019, p.2). A critical and often referenced example in this field of self-reflection comes from Bracey in his article ‘Why Students of Color Don't Take Latin’. Bracey examines the reasons behind why in America, students of colour typically do not opt to study classical subjects. Bracey, an African American Latin teacher from Massachusetts, shared his own personal experience in secondary school: ‘At no point in my mind did I think that would be a place where I would fit in. Based on the reputation of Latin, there is no way I would have tried it’ (Bracey, Reference Bracey2017). This piece, along with a student-written article ‘The Classics Major Is Classist’ (Bertelli, Reference Bertelli2018), together highlight the elitist nature of Classics within American culture - an elitism, I fear, that was learnt from Britain.

The study of Classics was brought to the colonial settlements of North America as part of the education of the elite. The ability to read Greek and read, write and speak Latin gave children of the elite a path straight into college and then into positions of rank in the state or church (Wyke, Reference Wyke2012, p. 12). In the UK, prior to the 1960s Latin was a gateway into the most prestigious universities in the country. One could not attend Oxford or Cambridge without an O Level in Latin, regardless of their degree (McMillan, Reference McMillan2015, p. 26). As Forrest notes, it was mostly in independent and grammar schools that students got the opportunity to study Latin, and it was rare for students to study the subject in the state sector (Forrest, Reference Forrest2003, p. 44). Thus, Latin was a gateway to Oxbridge wide open to the elite and privileged, yet often barred to those who attended state schools or were of a lower social class. Still today Latin and Ancient Greek are most commonly taught in the private sector meaning that only a small, wealthier percentage of the country have access to these subjects. In the Cambridge Assessment analysis, for the percentage of students taking GCSE subjects in 2017, the ratio of state:private examination entries at GCSE is around 1:2 for Latin and 1:10 for Greek (Gill, Reference Gill2018, pp. 6–7).

Yet whilst universities and scholars grapple with these discourses on Classics and social class, Joffe notes that younger students are also becoming aware of this growing movement and claims that classrooms are changing as a result and that as teachers ‘…we must better equip ourselves as instructors to have these difficult conversations with [students]’ (Joffe, Reference Joffe2019, p.2). Many scholars would argue that there has always been a place within the Classics classroom to approach sensitive and controversial subjects (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016; Sorkin Rabinowitz & McHardy, Reference Rabinowitz N and McHardy2014). Thus, if there is room to tackle subjects like slavery or the treatment of women, then arguably there is room to promote social justice as well. It is clear within other subjects of the school curriculum that teaching students how to approach and address sensitive topics is considered a vital part of the education system. Claire and Holden (Reference Claire and Holden2007) advocate in their book ‘The challenge of Teaching Controversial Issues’ that whilst it can be ‘safer’ to steer clear of controversial issues and topics in the classroom, we cannot nor should we deny to our students the reality of the world we live in.

Learning how to deal with sensitive or controversial topics in a structured setting, through topics introduced into the classroom, can be a rehearsal for dealing with more immediate controversy in the playground, home or community. It is also a part of preparation for living in a democratic society where controversial topics are debated and discussed without recourse to violence. (Claire & Holden, Reference Claire and Holden2007, p.43).

Hunt, along with many other classicist educators, believes that Classics should be no different (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p.31). This notion is exemplified by the Department of Education, who promoted the study of Classics in their pamphlet Curriculum Matters: Classics from 5–16 by highlighting the distinctive contribution Classics could make to a student's education and their understanding of controversial issues in the world around them. According to the text, ‘…there are two main reasons for studying the classical world: its intrinsic interest and its capacity to increase pupils understanding of themselves and of the world in which they live’ (DES, 1988, pp.1–2). Through exemplars of ‘moral judgements and religious views drawn from other societies’ Classics could provide students with ‘valuable points of entry into some central questions of human life’ (DES, 1988, 8). The document continued:

Discussion of Greek or Roman attitudes to slavery, the status of women in society, the Olympian gods or gladiatorial contests can help them to articulate fundamental moral questions, discover something of the cultural conditioning on which many of a society's judgements depend, and gain a greater sensitivity to and tolerance of the diversity of values and religious practice in their own world. (DES, 1988, p. 8).

Thus, many would argue that if there is already a space for addressing sensitive topics in the Classics classroom, then ideas of social justice could also have a place. Whilst the use of Classics to advance social justice can be seen as contentious, I would argue that the critical awareness surrounding the Classics discipline being used to promote and uphold elitist ideology, both historically and in the present, and the subsequent movement to eradicate this ideology moving forward, can be seen as a critical consciousness within the discipline. Freire's ‘freedom from oppression’ can be achieved as teachers and practitioners seek to diversify and improve the inclusivity of the classics classroom (Freire, Reference Freire2002; Mustakova-Possardt, Reference Mustakova-Possardt2003). The Classics educationalist Sharwood Smith in his book ‘On Teaching Classics’ (1977) advocated that teachers have a responsibility not only to follow the syllabus but also then to utilise elements of this in order to prepare students for adulthood. In this way teachers would be providing not only ‘an education in Classics’ but ‘an education through Classics’ (Sharwood Smith, Reference Smith J1977, pp. 4–9). Inspired by the DES pamphlet, I decided to centre my research project around Roman slavery with the hopes of helping my students gain that ‘greater sensitivity’ towards the subject. Conscious of the articles written by Robinson and Bostick, as mentioned in my introduction, these two American high school teachers discussed their own personal experiences of dealing with students’ perceptions of slavery influenced by their textbooks and so I was motivated to focus my research more closely into how influential the CLC's approach to teaching the sensitive topic of slavery was on my students.

Examples of Latin teaching sensitive topics

The discussion so far has revolved around the discipline of Classics in general and its role in advancing critical pedagogy by teaching students to think critically about the world around them through the medium of Classics. However now I would like to consider the role Latin solely can play in the classroom and in particular, the CLC. Thus, I now want to consider some examples of the CLC being used to discuss controversial topics and look at some evidence for the presentation of stereotypes in Latin course books specifically, as my interest lies in the presentation of slaves.

The study of Latin in the UK often involves the study of literature and the society of the Romans through the medium of the Latin language. Therefore, many students are exposed to sensitive topics from Roman society. The CLC is by far the most popular of the UK Latin course books, with an estimated 90% of the Latin course book market share (Cambridge School Classics Project, 2015; Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p. 32). The CLC follows the reading-approach method using stories and a continuous narrative which contains many sociocultural topics often introduced both through the characters and stories in Latin and then through cultural background information at the back of each stage. As Hunt summarises, in Book one of the CLC, which is typically taught during KS3, students are introduced to topics such as the role and treatment of women (Stages 1, 3 and 9), Roman attitudes to slavery (Stages 3 and 6), perceptions of foreigners (Stages 3 and 10), and of religious minorities (Stage 8), beliefs on death (Stage 7), and to the everyday violence of the gladiators (Stage 8). These sensitive topics are not explicitly highlighted by the CLC; however, they are there for teachers to use to elicit discussions. Thus, it is the role and duty of the teacher to address these issues and guide students towards a critical consciousness by allowing them to engage critically with the content (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p. 32). As Sorkin Rabinowitz and McHardy note, by addressing these topics, the subsequent open discussions of issues of race and social class can make studying Classics attractive as well as be beneficial to students. (Sorkin Rabinowitz & McHardy, Reference Rabinowitz N and McHardy2014, p.4).

The benefits of teaching diversity through CLC have also been researched. Barnes (Reference Barnes2018), in his research paper ‘Developing students’ ideas of diversity in the ancient and modern worlds through the topic of Alexandria in the CLC, Book II’ highlights how the central aspect of his study was the student responses to the cultural diversity in third century Alexandria presented to them in the second book of the CLC (Barnes, Reference Barnes2018, p.5). These opinions developed by teacher-led discussions included sensitive issues surrounding race and ethnicity. In the cultural background material on third century Alexandria presented in CLC Book 2, students are introduced to discourses of power in which lighter-skinned Greeks and Romans have imposed colonial superiority over the native, darker-skinned Egyptians. Furthermore, students encounter Egyptian characters as members of the lower classes, either as slaves or craftsmen, whereas the European Greeks and Romans are members of the cultural elite (Barnes, Reference Barnes2018, p. 5). In her paper, ‘Latin for All Identities’ (2016), Sawyer advocates the importance of acknowledging diversity and also representing it in the learning environment and in the school curriculum (Sawyer, Reference Sawyer2016, p.35). Sawyer claims that the representation of diversity, where it goes unacknowledged and remains invisible, is an issue as ‘cultural privilege’ would then enable ‘people of majority groups to go through life with more ease than other groups’(Sawyer, Reference Sawyer2016, p.35). Sawyer proposes that our goal as teachers should always be to include and represent members of all identifies in our classroom, and that within Classics there are many opportunities to do so, in mythology, poetry and history (Sawyer, Reference Sawyer2016, p.35). Bracey acknowledges through his own experience of teaching Latin that it is very easy for the ‘most well-intended teacher’ to ‘alienate’ students of colour through the teaching of the CLC which contains a positive and uncritical presentation of Roman imperialism, and a lack of images of people of colour (Bracey, Reference Bracey2017). However, as Arab and Earl (Reference Arab and Earl2011) note, there is a bias towards the representation of Persians and the near East within the Classics teaching community suggesting ‘many European academics and scholars still appear so caught up in the idea of European identity being founded in the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome, but the simultaneous and often predating achievements of eastern civilisations seem only of interest in so much as they relate to their own supposed European forefathers’ (Arab & Earl, Reference Arab and Earl2011, p.11). Thus, when teaching about diversity it is important that teachers and historians alike think critically about the presentation of these cultures and not just as a reflection of Greek or Roman ideology. Arab and Earl strongly advocate for teachers to address issues of cultural relativism within the Classics classroom to enable pupils to look at the people who form the subject of their studies from a multicultural viewpoint. They conclude, ‘Where does the near eastern world and its influence on the European world belong in European teaching? A Europe whose schools are populated with peoples originating from these countries[?]’ (Arab & Earl, Reference Arab and Earl2011, p.13). This idea strengthens Sawyer's argument to acknowledge diversity in the classical world as within our own diverse classroom, and, as Barnes has noted, the CLC provides the perfect opportunity for the teacher to do so. Barnes claimed that his students enriched and deepened their perceptions of the diversity of the ancient world, concluding that ‘Involving students with different perspectives in the Ancient World can produce new insights and positive engagements with Classics in the classroom’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes2018, p.9). Bracey in his article ‘Restoring Color to the Ancient world’ advocates the importance of representing and teaching Rome as the multi-racial society it was, not just for the sake of historical accuracy but also so that all types of students feel represented (Bracey, Reference Bracey2020).

Thus, there seems to be ample opportunity within the CLC to enrich students’ ideas surrounding sensitive topics such as slavery. However, whilst the opportunity to address sensitive issues such as cultural diversity is presented in the subject matter of the CLC, as the research of both Barnes (Reference Barnes2018) and Arab & Earl (Reference Arab and Earl2011) make clear, the CLC is still promoting aspects of the ancient world which are problematic. We as adults and teachers may know how to pick these issues out and help the students negotiate the latent issues in the text and images. However, for the students, they will often take their textbooks at face value and their perceptions are coloured by first impressions. Does the CLC override these first impressions or are teachers needed to help students guide and unpick these latent issues. In regard to slavery, the students only know Grumio and Clemens and their happy lives working for Caecilius. It is not till Stage 6 that the CLC addresses this presentation and introduces the concept of slavery as bad. Is that enough to override the student's positive introduction to slavery or is a teacher's help needed to fully tackle these issues. The CLC's latent cultural bias in the presentation of diversity further cemented my desire to research the presentation of slavery, to see if perhaps there is a running theme of bias with the CLC's presentation of characters.

Presentation of slavery in Classics textbooks.

Whilst there has been a lot of research advocating the promotion of multiculturalism in the classroom and questioning the presentation of women and diversity within the CLC, there has not been much research on teaching the sensitive topic of slavery and the presentation of slaves within Classics textbooks. However, there does appear to be a clear concern about the presentation of slaves within Latin textbooks. Bostick, an American Latin teacher, wrote in an article for in medias res (an online magazine published by the Paideia Institute), how it is impossible to teach or learn about Latin without encountering slavery and because of the role slavery played in America's history it is vitally important that Latin teachers teach the subject accurately (Bostick, Reference Bostick2018). Although in the USA, the word ‘slave’ does have a particular nuance and powerful historical presence, the ideas presented by Bostick about teaching slavery in the US still have a strong resonance in the UK. Britain was the leading slave trader in the North Atlantic between 1640 and 1807 when the British slave trade was abolished, It is estimated that Britain transported 3.1 million Africans (of whom 2.7 million arrived) to the British colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries (The National Archives). In the same way that Classics is undergoing a vast reform in regard to social consciousness and decolonisation, the British History curriculum has also been criticised in the past by teachers and academics for its inherent bias and emphasis on British History and nationalism. An anonymous article in The Guardian written by a teacher laments how ‘…pupils are brought up learning about the strength and heroism of this country and its once ‘grand’ empire rather than about how other countries have suffered under its rule’. (The Guardian, 2018). Slavery is accepted as a defining historical element in the shaping of the Western World and its abuses are common educational themes in modern history, both in the US and in the UK. However, it can be noted that slavery carries different modern-day political ramifications depending on the country it is taught in. By looking at the apparatus of slavery in the ancient world, students are afforded a different, more objective critical engagement with the topic, helping them gain a critical consciousness which can then be applied to modern history or any other subject where the topic applies.

In the case of Bostick (teaching in the US), she teaches Latin using the Ecce Romani course and laments how the presentation of Davus, an enslaved person met in Chapter 3, could lead students to believe that ancient slavery was ‘tolerable, even acceptable’ (Bostick, Reference Bostick2018). Throughout Ecce Romani, Davus’ life is portrayed as quite pleasant and he has a positive opinion of his master. For example, during a story in the first Ecce Romani book, a new slave has arrived at Cornelius’ house and Davus, the overseer slave, shows him around and answers questions. When the new slave says ‘The slaves of Gaius Cornelius are happy. Do they love their master?’, Davus responds ‘Sure! I am the overseer of a good man!’ (Ecce Romani, 1982, p. 55). We learn from the culture section ‘The Slave Market’ in the course book that after Davus was purchased, he was initially worried about his future with his new master, but that ‘…he needn't have worried. Old Titus proved to be the kindest of masters’ (Ecce Romani, 1982, p. 37). Bostick states that it was this kind of repetitive rhetoric that led many secondary students to gain the impression that ancient slavery was ‘not that bad’. Even though Ecce Romani does acknowledge the poor treatment of some slaves, Bostick argues that reducing the institution of slavery to a mere question of mistreatment is ‘superficial and fails to capture the horrors of the larger institution’ (Bostick, Reference Bostick2018). Even if Davus had a kind master, students needed to understand that all slavery was a dehumanising abomination. The presentation of slaves in Ecce Romani sounds rather similar to that of the CLC. Bostick circumvented the Latin coursebooks rhetoric by teaching students to think critically about the language used to talk about slavery in English as well as discussing the history of slavery in the ancient world. Bostick concludes that it is vitally important to present students with a richer definition of slavery that goes beyond the information in the textbook; this allows students to understand ancient slavery and also ‘…avoids feeding into dangerous myths and misconceptions about American slavery’ (Bostick, Reference Bostick2018). This concluding statement of ‘American slavery’ can easily be changed to apply to the UK teaching of the transatlantic slave trade in the school curriculum.

Dugan, in her research on the verbal and visual presentations of slaves in Greek and Latin textbooks, discovered ‘a complex web’ of discourse surrounding slavery and comedy resulting in the ‘happy slave narrative’ (Dugan, Reference Dugan2019, p.62). Dugan identifies the ‘happy slave’ narrative as ‘the systemic portrayal of enslaved people as joyous recipients in the institution of slavery’ which often ‘emphasises the quality of provisions and lodgings for enslaved people along with their loyalty to and close friendship with their enslavers’ (2019, p.63). This narrative reflects back to Greek and Latin literature where depictions of slavery were often intertwined with comedy, and enslaved people were common central characters in ancient comedy. Furthermore, modern Classics textbooks reflect such a traditional narrative through their word choice, rhetoric and supplementary visual materials. As Robinson notes, the presentation of slavery in the CLC seems to be purposely designed to reflect the characterisation of slavery in ancient texts (Robinson, 2017). Thus, the CLC provides students with the ‘Roman attitude’, allowing slaves to be viewed in a comedic sense. Dugan concludes that, unfortunately, this sanitation and normalisation of slavery as demonstrated by the characterisation of Clemens and Grumio in the CLC has enabled the uncomfortable topic of slavery to be made comfortable for students and to enable them to escape the much-needed critical analysis that would allow them to deepen their understanding about the reality and horrors of the ancient slave trade (Dugan, Reference Dugan2019, p.69). After reading about this pervading narrative of ‘happy slaves’ and considering the experiences of two Latin teachers (Bostick and Robinson) and their perceptions about how this narrative has affected the beliefs of their students, I became interested in whether the presentation of slaves in the CLC did have an effect on students’ ideas on Roman slavery.

Research Question

The focus of my research will be how much the students understand about the presentation of slaves in the CLC gained from reading the stories and looking at the pictures. To guide my research, I broke down the broader title of my study into three research questions;

1. How do students perceive the characterisation and presentation of slaves in the CLC?

2. What the range is of student responses- how broad are they?

3. What do students think of their own perceptions? Do they think the characters Grumio and Clemens are accurate representations of Roman slavery?

Methodology

As my study is focused on the issue of the happy slave narrative within Latin textbooks by investigating students’ perceptions of slaves in the CLC, therefore, after researching more widely into different educational strategies to guide my research plan, I found that a case study would be the most suitable approach for my research title. As Taber states, a ‘case study is often used when we want to develop a clearer, more detailed picture of something, or to understand what is going on in some complex situation’ (Taber, Reference Taber2013, p.145). My study has identified the complex situation of the presentation of slaves and how that may affect student perceptions. My research followed the instrumental case study approach as I am interested in following a ‘general theoretical issue’ as opposed to studying a case because there is an intrinsic interest that relates to my own professional practice (Taber, Reference Taber2013, p.155). Taber defines this general interest as:

Where a teacher-researcher selects one class, one lesson, one topic, one group of students, as a suitable context for undertaking theory-directed research, rather than because the issue derives from concerns about that class, topic, etc. (Taber, Reference Taber2013, p.156).

As the focal point of my research is on student perceptions, I wanted to investigate how the complex educational phenomenon of the ‘happy slave’ was received within my own classroom so that I could develop an understanding of the issue. However, bearing in mind the common criticism of teacher bias in critical pedagogy, I did not want to influence my students’ opinions nor suggest that there could be an issue with the presentation of slaves in the CLC. One disadvantage raised about case study research is that it can be difficult to generalise from a single case (Simons, Reference Simons1996, p.225). However due to the already small-scale nature of this research, the scope of my enquiry was limited in terms of time, content and student participation, and therefore I would not be able to generalise from the results anyway. However, that does not mean my case study cannot produce useful results, as ‘a case study can generate both unique and universal understandings’ when focused through an in-depth and holistic perspective (Simons, Reference Simons1996, p.225).

Research methods

Using my research questions as a guide, I wanted to carry out research methods that would gather the most effective evidence in a case study. I initially decided on two methods: a questionnaire and student interviews. My questionnaire was directed towards the entire class and allowed me to survey the opinion of all students in it, asking identical questions of each student but also receiving more individualised responses using some open-ended questions. My interviews were intended to be semi-structured with six students randomly selected from the class and interviewed together in three sets of pairs. My reasoning behind the semi-structured interview was it would allow the students to comment and express fully their ideas. Interviewees can talk in depth and choose their own words. I would be able to probe their responses and develop a real sense of the students’ understanding of the presentation of slaves (McLeod, Reference McLeod2014).

However due to the government shut-down of schools I was unable to carry out my group interviews with students and so had to adapt my research and so instead, students were emailed the interview questions and they provided written responses. Whilst I was unable to further probe their responses and gain deeper insight into their opinions, there are still benefits to using written data while conducting research, particularly concerning sensitive issues. Nesbitt in ‘Researching Children's Perspectives’ (2000) advocates that individualised, written responses to a series of questions can prevent any ‘individualised blocking in the conveyance of student meaning’. Furthermore, Nesbitt highlights how, particularly when discussing sensitive topics, allowing students to write down their opinions is important as it can prevent any experience of embarrassment from the student (Nesbitt, Reference Nesbitt and Lewis2000, p.137).

Teaching sequence

I have chosen to focus on a Year 7 class, comprised of 30 students, as in my placement school students are first introduced to Book 1 of the CLC and the slave characters in Year 7. For many students in the class, the start of Stage 6 in the CLC will be their first formal introduction to Roman slavery. Thus, I wanted to investigate their initial perceptions of slavery that have not been developed through years of studying the ancient world. Furthermore, this Year 7 class I had taught since the beginning of my placement, so I felt that the class was more suitable as I knew the class well. As my research was focused on student voice and opinion around slavery and not content or activities, I did not plan a sequence of teaching lessons. However, I did structure a sequence of lessons around my questionnaire and the interviews I intended to carry out. I wanted the class to complete their questionnaire before I started teaching them about the background of slavery as I did not want to influence their perceptions of the CLC's slave characters Grumio and Clemens with information about some of the realities and horrors of Roman slavery. For many of the pupils until those background lesson on Roman slavery in Stage 6, their only point of reference for Roman slaves in an educational setting came from the characters of Grumio and Clemens. Therefore, I only gave a brief introduction to my research and explained I was investigating student perception of slave characters in their textbooks.

The questionnaire asked students to consider the ways Grumio and Clemens are represented in pictures and the ways in which they engage with other characters in the Latin stories. I provided the students with a checklist of pages where the slaves appeared previously in the book up until Stage 6 (see Table 1 below). I provided prompts with each section to refresh students’ memories of plot or of what is happening in those pictures as well as prompting questions to provide a starting point for their responses. Students were asked to check through their textbooks to the relevant pages and to note down any thing they could observe or tell from those pictures and stories about Clemens’ and Grumio's characterisation and relationships with other characters. Before the students started to answer the questionnaire, I talked them through each section as well and added further explanations about what they needed to do. I dedicated 20 minutes to this questionnaire as students only needed to write short responses; however, I was flexible with my timing to allow students adequate time to go over all the sections. I did not want to influence student opinions of Grumio and Clemens, so I waited until after the questionnaire to start focussing on the history of Roman slaves to provide them with richer knowledge about the ancient slave trade.

Table 1: Questionnaire sections

I intended to conduct my interviews after the students had their background lessons so that they had deeper understanding of the Roman slave trade. However, due to delays in getting parental permission to record and then transcribe these interviews for data, I was unable to conduct these interviews in person before schools shut.

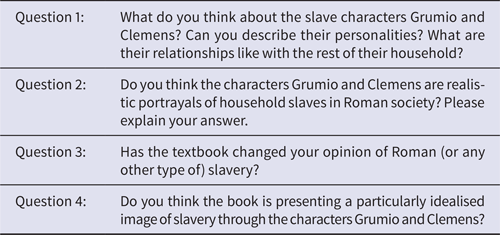

Table 2: Interview questions

Data and Findings

In this next section I shall present the key aspects of my data collated from the questionnaire and extracts from the written interviews. Five students participated in the written interviews and have been given fake names for the purposes of this report; Alex, Bea, Charlie, Daya and Emma. I have collated the responses to the questionnaire into tally charts so that I can determine the range and frequency of the student opinions and ideas. It should be stated that due to the nature of my sample size I will only be drawing tentative conclusions from this data in the light of the literature which has been discussed previously.

My questionnaire was mainly focused on the first of my research questions, how do students perceive the characterisation and presentation of slaves in the CLC? However, by collecting the student responses and turning them into tally charts recording the frequency of ideas I am able to consider the range and breadth of student responses. In order to identify the breadth of responses I have identified whether the student's opinions suggest a positive, negative or neutral response concerning their perceptions of the representation of the slaves.

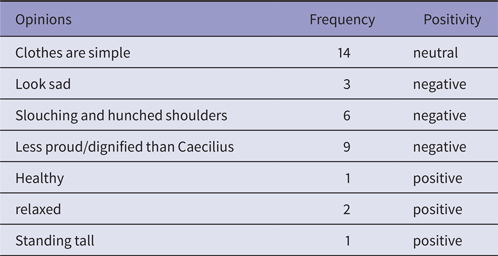

Sections 1 and 2 are concerned with the initial pictures where we are introduced to Grumio and Clemens and students took note of how the slaves are presented and what the pictures tell us about their roles in the household.

Table 3: Section 1

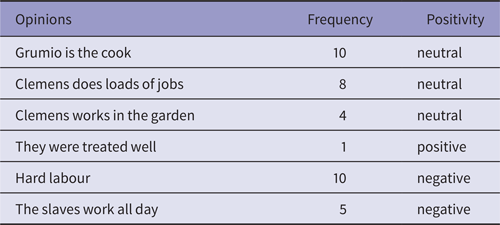

Many students seemed to compare the opening pictures of Grumio and Clemens on page 3 to those of the rest of the family, noting that the slaves wore simple clothes and had a different posture to those of the free upper-class family members. Interestingly in Section 2 (see Table 4) ten students identified the pictures showing their roles within the household as depicting ‘hard labour’ perhaps in reference to Clemens working in the garden. There was only one positive response to those pictures ‘that they were treated well’ whilst the remaining were neutral or negative.

Table 4: Section 2

Section 3 asked students to turn to the story Cerberus and focus on the line at the end of the story ‘The cook sleeps in the kitchen’ and were asked what that told us about Grumio's character. Here the responses vary. There is a division between 17 students who believe he is sleeping because he is tired or working hard whereas nine students believed he is sleeping as he is laid back and lazy. Perhaps this idea of the slaves being worked hard is continuing from the responses shown in Table 4. Some students reasoned the kitchen doubled as Grumio's bedroom so saw no issue with him being asleep. Seven students characterised Grumio as hard-working in a positive sense and thus excused his need to sleep during the day. Interestingly two students believed that Grumio felt there would be no repercussions or consequences if he was caught sleeping by his master. Another student also identified that he was free to do what he wanted. Within the stories we never see Grumio or Clemens punished for sleeping or not fulfilling their roles as slaves which may explain why the students believe this. I identified these two points as positive as they depict as positive image of slavery whereby the slave is confident that he will not receive violent punishment for disobedience.

Table 5: Section 3

Section 4 (Table 6) referred to the opening sentences of Stage 2 when a friend came to visit the familia. The friend greets all the members of the family including Clemens and the students were asked how Clemens was treated by this person from outside the family. The majority of the class believed that, because the friend acknowledged Clemens and included him in his greetings, he was showing respect to the slave and treated him in a warm and friendly manner, thus having a positive response to the depiction of slavery. One pupil however noticed the difference in the pictures stating how the friend greeted the rest of the family warmly often touching them, but with Clemens he was ‘distant’ as in the picture he greeted him from across the room.

Table 6: Section 4

Section 5 (see Table 7) focused on Grumio's relationship with Metella. The cook has prepared a meal for the family and Metella has come to taste it. The text states that Grumio is anxious and the students were asked what this told us about his relationship with Metella. The class was split between positive and negative responses. I identified Grumio's desire ‘to avoid punishment’ as negative as it is reflective of the idea that there will be a stronger negative outcome if he displeases Metella than just being told off.

Table 7: Section 5

The final section, Section 6 (see Table 8) asked students to look at the end of the story in triclinio when Grumio comes into the dining room and eats the food he prepared and drinks the wine while his master and guests sleep on. We are told that the slave ‘dines in style’; students were asked what this story tells us about Grumio's character. Again, we see evidence of Grumio acting naughtily and four students identified that Grumio knows he will not be punished for his actions and three other students acknowledged that he has a lot of freedom and is treated well. One student said that Grumio was ‘clever’ to wait for his master to be asleep so he could get the good food whilst two other interpreted this as Grumio being ‘sneaky’.

Table 8: Section 6

For my interview questions I wanted to move from asking the students personal questions about their opinions of the characters Grumio and Clemens to more conceptual questions on their thoughts on whether the textbook was being idealistic in its presentation of slavery. The students’ full responses have been provided within the appendix at the end of this report. For Question One students were asked in general what they thought about the characters Grumio and Clemens, expanding on the questionnaire. Alex, Charlie and Daya all stated that they thought Grumio and Clemens were ‘happy’ and Alex, Bea, Charlie and Daya all thought the slaves were treated well, had good relationships with their masters who provided for them and they had a lot of ‘freedom’. Emma, however, said despite having a good relationship they were still treated like lower citizens and were not equal to their masters. These opinions on the slave characters fit with Dugan's definition of the happy slave character as ‘joyous recipients in the institution of slavery’ and having ‘close friendship with their enslavers’ (Dugan, Reference Dugan2019, p. 63). So it is interesting to see that the students picked up on this.

My next question, whether the students thought these characters to be realistic portrayals of household slaves in Roman society, allows us to see how much the students understand about the presentation of slaves in the CLC. The students were mixed in their responses. Alex and Bea thought they were unrealistic because some slaves would have been beaten by their masters. In contrast, Charlie, Daya and Emma all thought they were realistic: although some slaves did have cruel masters, they thought, some masters treated their slaves in a kindly way and Clemens and Grumio were portrayals of that. Emma stated: ‘Some slaves would not have liked being slaves and wanted to be freed, whilst others would have been happy like Clemens and Grumio’. This again repeats the idea of happy slaves. To Emma, it seemed realistic to presume that some slaves would be happy being slaves because they could see it demonstrated by the CLC. This kind of belief could be problematic if transferred in the student's mind to modern slavery. However, in the next question when asked if the textbook had changed their perceptions of Roman or any other slavery, Emma disagreed, saying that they still thought slavery was wrong. What the textbook had taught Emma was ‘about the lives they [the slaves] led away from the work they did and that they can be freed’. Alex pointed out that the apparently positive portrayal of Clemens and Grumio had not changed her opinion of slavery as every Roman household would have been different. Bea stated that it did change her opinion, saying initially she thought slavery was a cruel ‘job’ but now she knows that not all the slaves get treated like that and some are treated as if they ‘were a normal man and not a slave’. The language used to describe slavery so far by these students seems to liken slavery to being similar to a ‘job’, with Grumio and Clemens having work to do, but also having time off to go to the theatre or meet up with their girlfriends. Daya wrote: ‘Yes, it has made me see why there was a point of slaves, and now I can come to the grip with that it is acceptable for some reasons.’ This opinion follows in line with what Bostick found when teaching slavery in an American high school that students found Roman slavery to be ‘acceptable’ (Bostick, Reference Bostick2018).

Finally, I asked students if they felt the textbook presented an idealised image of slavery. As I was not there to explain the question, I added a definition for idealised as perfect or better than in reality so that students understood the clear difference between this question and Question Two which asked if it was realistic. Bea agreed saying, ‘Life as a slave in real life wouldn't be as nice as Grumio's and Clemens’.’ Charlie said that Clemens and Grumio presented ‘one image of slavery’ and suggested that the textbook should have a broader range of slave characters to include ‘different ways slaves were treated’. Daya said that Grumio and Clemens did reflect an idealised image, although the textbook also showed ‘some of the struggle that different Roman slaves go through’. Here Daya is probably referring to the background section of the textbook that does reveal that slaves were not considered ‘human beings’ (CLC: 1, 1998, p. 78). Emma claims the book is idealised as ‘it only shows the good parts of their lives’ and the work they are given is ‘easy’. Through these interviews these students showed awareness of some of the cruelties that ‘other slaves’ may have suffered from cruel masters or from working in coal mines or in agriculture. They tended to have a simplistic view of Grumio and Clemens having a happy life. To them the biggest problem that they perceived about Roman slavery was dependent on who your master was or what your job/role was, not the inherent evil of slavery itself. This research thus raises further questions: is it a problem that the students can accept or reject Clemens and Grumio as realistic or idealised examples of slaves, but that they ignore the fundamental problem of the idea of slavery? Although one may be inclined to conclude that the Latin stories of the CLC of itself do present a sanitised image of slavery that students appear to pick up on, it is important to consider whether this is a matter of pedagogy: is the CLC misleading in its presentation of slaves: or is it a matter of maturity? This research was carried on a singular class of Year 7 students after all. Whilst it has been established that sensitive topics are present in the CLC, they are not highlighted or discussed deeply. It is up to the teacher to decide whether to draw out discussions about slavery. One would hope the teacher would go into greater detail and present different perspectives on slavery. However not all teachers will have the time to do this. Some teachers will only be able to focus on the stories themselves. In the stories our slave characters are likeable, the situations they find themselves in are mildly comic but never distressing and, overall, the visuals and texts present a comfortable and sanitised view of the Roman world and Roman slavery. Regardless of the age of the students, it is important to acknowledge that it is a problem that the CLC does this. If the teacher feels the need to excuse the representation of the Roman world which the textbook displays, then the book is misleading and wrong and thus should be considered unsuitable for today's classroom.

Conclusion

My study investigating students’ perceptions of slavery in the CLC has raised a number of interesting points. It seems the fears raised by Robinson (2017) and Bostick (Reference Bostick2018) about the trivialising nature of the CLC's presentation of slavery could lead to students becoming desensitised to the topic. Furthermore, as Dugan notes, this presentation of ‘happy’ enslaved people is a narrative that has transcended time and place. Dugan advocates for critical thinking both in the classroom and by textbook makers themselves so that the Classics community can grow beyond ‘the centuries of desensitisation to the violence and inhumanity of enslaving another human being’ (Dugan, Reference Dugan2019, p.54). Although my research is small scale, I do believe there may be an issue with the presentation of slavery within the CLC based on the perceptions of my Year 7 class towards the characters Grumio and Clemens. Whilst the books are pitched towards children within KS3, the textbook, by creating these light-hearted slave characters who have nice masters and do not appear to suffer at all, has made the topic of slavery comfortable. However, as Dubois notes, it is sometimes our job at teachers to make students uncomfortable (Dubois, Reference Dubois, Rabinowitz N and McHardy2014, p.187) and so I would advocate for teachers to encourage students to think beyond this presentation of slavery to consider the inherent evil of slavery itself.

Many teachers of Classics will naturally address the sensitive topic of slavery when it comes up in the CLC, which often starts on the very first page of the book as students are inclined to translate servus as servant instead of slave and thus the distinction is made in the first Latin lesson. However, as teachers we should be aware that it could be possible for students’ ideas of slavery to become confused. They know slavery is bad, a judgement they have learnt from society long before they enter a Classics classroom. But then they are presented with the stories of two slaves who seem happy and content with their lives. Whilst the background section of slavery, and I imagine most teachers, correct this idealised image to an extent by touching on the harsh realities of the slave trade, this image of the happy slave still nevertheless can be embedded into the students’ minds every time they read a story containing the two characters. Students gain a deep level of familiarity with these characters and clearly enjoy reading about their stories and characterisation. As teachers, I think it is important that we critically evaluate our own source material and fully consider the damaging legacy of teaching students about the happy slave. We should question what the purpose is behind presenting slave characters in this way: is it to reflect Roman attitudes towards slaves as witnessed in Roman comedies with the clever slave caricature? If so, how do students benefit from this presentation? Robinson notes how recovered reception in this way can be ‘problematic’ saying, ‘The Classics are objects for study, not revivification’ (Robinson, 2017). Ultimately this research has made me aware that just teaching students the background information from the CLC may not be enough to combat the notion of ‘acceptable slavery’. In the same way that educators should critically analyse the presentation of these slaves, we should encourage our students to do so as well.

Appendix

Question 1- What do you think about the slave characters Grumio and Clemens? Can you describe their personalities? What are their relationships like with the rest of their household?

Alex: Their relationship with the household seems very close, although not too close as Grumio did hold secrets that I can assume no one in the household knew about as he did it secretively and without them knowing, but on the other hand Clemens was once given the honour of carrying the wine and only slaves that were trusted were given this opportunity which shows that Caecilius trusts Clemens, giving me more reason to believe they are close and when the EX-slave came to visit Grumio prepared a fantastic meal and they were all happy and Clemens called Caecilius and the rest of the household to greet him and Grumio and the others were pleased and excited to greet him and the reason they might be so excited could be because they hadn't seen him in a long time and that means they probably miss him and this is further evidence on the fact that they are very close but we must remember that Grumio did holdback secrets from them but then again that was very personal. Another piece of evidence is when Quintus saved Clemens and Grumio from the dog that was in the streets and was attacking the and instead of teasing them Quintus helped them and they overpowered the dog and the slaves then praised. This gives me more reason to believe that they are close because Quintus also could have left them to die as dogs can also kill people well some dogs can. I think they have great personalities as they always seem happy vut one time Grumio was drunk and a painter was painting a lion and Grumio because he was drunk thought that it was a real lion and called Clemens and said ‘There is a lion in the kitchen {or somewhere} and Clemens replied with ‘and there is a drunk man in the kitchen’ and that made me laugh and it shows that Clemens is a bit more responsible then Grumio as he didn't get drunk, but that doesn't necessarily mean Grumio is a bad person, it just shows that he was having some fun, because you need that once in a while and if I didn't have that I would never be able to live.

Bea: I think Grumio and Clemens are treated well; they are well dressed, and they don't get beaten or hit by their masters. They have the freedom to go anywhere because Grumio goes to meet Poppaea and Clemens can go to the theatre. But they must do a lot of manual labour and Grumio doesn't have a separate bedroom (he sleeps in the kitchen).

Charlie: I think the slave characters Clemens and Grumio are happy where they live and get along like friends. They have a lot more freedom compared to other slaves. I also think they get along with the rest of their household because they have more freedom and that gives them more work ethic.

Daya: I think they were respectfully to their master, and were happy to do what they were asked for. I personally think that they were closer to their masters than other slaves they were sometimes even treated like equals.

Emma: The book doesn't really say anything about the personalities or the characters of the slaves but there relationship with the rest of the household is quite good compared to other households. They are still treated like they are a lower status and are not equal.

Question 2- Do you think the characters Grumio and Clemens are realistic portrayals of household slaves in Roman society? Please explain your answer.

Alex: I do not think they are as this could not be true in all households as there must have been lots of slaves who weren't treated in the right way though be true though it is very unlikely there is still a chance that it could be true. Although in a way they are realistic because they do some sneaking around like they once stole food of the table because they might have been hungry but it doesn't mean that they have been starved by anyone it most likely means that they were going to eat after the merchant had left and sometimes you just can't hold in your hunger and I would do that.

Bea: I don't think they are realistic portrayals of household slaves in the Roman society; some slaves get beaten if they do the slightest mistake, others have to do perilous jobs- working in the mines- without wearing the proper clothes or using the needed equipment. Grumio and Clemens must be lucky to have such masters as Caecilius and Metella as some don't have freedom and some don't get paid either.

Charlie: I think they are realistic in some ways because some slaves were treated kindly like that, but some slaves did not have as much freedom and did not enjoy working as much as Clemens and Grumio.

Daya: I think they are a type of realistic slaves. I think this as some masters were nice to their slaves and let them free once they have earnt it. But some different masters were cruel and tortured their slaves at any chance they could and treated them like dirt. I think Grumio and Clemens fit into the first type of master.

Emma: I think they are quite close to what real slaves would have been like but not completely accurate. As some slaves would not have liked being slaves and wanted to be freed, whilst others would have been happy like Clemens and Grumio. It also depends on the master because if they didn't like their master, they would have been sadder or quieter.

Question 3- Has the textbook changed your opinion of Roman (or any other type of) slavery?

Alex: No, it hasn't because in the book I don't think this example is necessarily true with all households as every household is different and not everything would be the same in every house because in other houses the masters might beat them or something like that. And some slave owners that are still around in Dubai pour hot oil over their slave for spilling something so not everything is the same around the world or even in one city or country.

Bea: The textbook did change my opinion of Roman Slavery. I thought it was a very boring and cruel job. It came in my nightmares when I was young as I was scared after reading a book about it. Now I know that not all the slaves get treated like that and some are treated as if they were a normal man and not a slave.

Charlie: It has changed my opinion a little bit, but it has also upgraded my knowledge on romans and roman slavery. It has made me realise that even today we have slaves that are treated as badly as that or even worse.

Daya: Yes, it has made my see why there was a point of slaves and now I can come to the grip with that it is acceptable for some reasons.

Emma: Not really, I still think it is wrong and people shouldn't have used them but the textbook has shown me more about the lives they led away from the work they did and that they can be freed. It also says what kind of work they did so how in many rich households there were more than one slave and that they all did different jobs.

Question 4- Do you think the book is presenting a particularly idealised image of slavery through the characters Grumio and Clemens?

Alex: I do not think so because not everything is the same everywhere and some masters might be even more lenient, and some slaves might work outside in the boiling sun and others might work in coal mines. Also, it is harder to work outside because you have the sun beating on you and if you work in a coal mine or underground it could be dangerous because of the air you breathe and the toxic gases in the air that are bad for your lungs and heart or other organs in your body.

Bea: Yes, because I don't think the slaves’ lives would be as good as the lives of Grumio and Clemens. There would be some struggles and disappointments and there would be less chances of the slaves going to the theatre. There are more chances of the slaves being punished and beaten than being praised. I think life as a slave in real life wouldn't be as nice as Grumio's and Clemens’.

Charlie: Yes and no. I feel like Clemens and Grumio presented one image of slavery. But the Latin textbook could have included a different type of way slaves are treated.

Daya: Yes, I do but it also shows some of the struggle that different roman slaves go through. So even though Grumio and Clemens are some of the better treated slaves we also understand what has happened to other slaves who were less fortunate.

Emma: Yes, their master Caecillius is nice and does not beat them. They were also allowed to go to the theatre but the book doesn't show them doing any of their jobs it only shows the good parts of their lives. It doesn't sound as if it is that hard a work that they do and that the work they are given is easy.