Introduction

Since the construction of the Channel Tunnel between France and the United Kingdom (UK), the French port city of Calais has become a major transit point for irregular migrants and asylum seekers wishing to enter the UK. The UK is a favourable destination for migrants and asylum seekers mainly because of the language, family/friends’ connections, and ease of finding jobs.Footnote 1 The migrants and asylum seekers started building makeshift camps around the port, which came to be infamously known as the ‘Calais Jungle’. At the peak of the European refugee crisis in 2015–16, these camps housed around three to nine thousand people.Footnote 2 The large presence of asylum seekers in Calais is often a matter of contention between the UK and French governments, with both sides blaming each other for the situation.Footnote 3 Local mayors of Calais and the UK border town of Dover characterised the situation as an exceptional security issue that only calling in the Army could address.Footnote 4 As migrants and asylum seekers attempted to hitch on trucks heading to the UK, migrant groups often threatened and attacked truck drivers driving from Calais to the UK.Footnote 5

Before the emergence of social media, the problems truck drivers faced received marginal attention in news media. The few reports that mentioned these incidents were mostly in textual forms with no eyewitness videos to support the story.Footnote 6 Since 2010, as the use of social media became more prevalent, truck drivers and travellers in Calais started posting videos online that depicted the violent acts committed by asylum seekers camping in Calais. These eyewitness videosFootnote 7 showed asylum seekers throwing stones, blocking roads with logs and concrete blocks, and breaking into trucks. The videos not only attracted news media coverage but also significantly affected the European public's perception of refugees. The image of a malevolent refugee engaged in violence and deceit challenged the traditional image of a vulnerable refugee fleeing war and persecution.Footnote 8 The eyewitness videos truck drivers and travellers in Calais captured contributed to the latter visual discourse as they were regularly remediated with security articulations to mobilise anti-refugee sentiments during the European refugee crisis.

Eyewitness videos powered by the remediation network of social media has significantly enhanced the agency of non-elites in politicisation and securitisation of issues. Videos captured by ordinary citizens acting as eyewitnesses have increasingly triggered political and security debates around issues that mainstream media and government have often ignored or suppressed, as witnessed during the Arab Spring protests, Syrian conflict, and recent protests in Belarus. The sense of authenticity and immediacy associated with eyewitness videos can disrupt official government narratives and frames of mainstream media.Footnote 9 In news media and journalistic discourses, eyewitness accounts have been traditionally perceived as authentic because of their proximity to a news event.Footnote 10

Spurred by the visual turn in International Relations (IR),Footnote 11 the role of visuals in international politics and security studies has received increasing attention in the last two decades.Footnote 12 However, the existing research on visual IR and securitisation has focused mainly on visuals produced by news media or similar professional sources. The production, visual, circulation, and audiencing aspects of eyewitness videos is significantly different from those of news media and therefore can potentially articulate (in)security in distinct ways. The role of social media in facilitating political-security meanings during a visual's remediation has also received less attentionFootnote 13 in these works. Since the advent of social media, the meaning-making of visuals has undergone a major transformation with regard to material-technological and social conditions.Footnote 14 Social media communication constitutes a new visual culture, where a visual's meaning is constantly remediated through a complex network of actors with varying positional powers. Ganaele LangloisFootnote 15 calls this recontextualisation as ‘new conditions for the production and circulation of meaning’ that have emerged with social media communication.

Eyewitness videos and their remediation through a complex network of social media users presents new political-security implications for the discourses of migration and refugees. Scenes of asylum seekers walking along the streets of Europe, throwing stones at trucks, breaking border fences, and protesting at train stations constitute a sense of exceptionality and irregularity worth capturing for the host population. Though professional news media covered these events through traditional frames of migration, not much is known about how eyewitness videos bring about political-security meanings. During the course of the European refugee crisis, eyewitness videos were constantly remediated to mobilise anti-refugee sentiments and reinforce the threat asylum seekers posed. The factors of the eyewitness video genre and social media that facilitated the constitution of these scenes through discourses of threat and danger need further examination.

Drawing theoretical insights from the literature of visual security, migration studies, and eyewitnessing, this article holds that the factors of epistemic-political constitution of eyewitness videos and the online remediation of eyewitness videos through the complex networked act between the ‘calculated security publics’ and video recommendation algorithms of social media play a key role in shaping political and security articulations. This is illustrated in the analysis of two eyewitness videos from Calais that a traveller and a truck driver captured. The study of the political-security implications of eyewitness videos for the issues of migration and refugees offers an empirical contribution to the visual IR literature, which has primarily focused on the genre of professionally produced visuals,Footnote 16 such as photojournalism,Footnote 17 editorial cartooning,Footnote 18 and comics.Footnote 19 The article also highlights how eyewitness videos and social media empower non-elites to play a more decisive role in securitisation processes, especially in cases where the perceived threat is recurrent and routinised.

The article is structured into six parts. The first section provides a brief overview of the securitisation literature and discusses the agency of non-elites in securitisation processes. The second section presents a literature review of the visual politics and security studies in the post-positivist tradition of IR, especially in the field of critical security studies. In the third part, I explain how the factors of the epistemic authority of the eyewitness video genre and online remediation of eyewitness videos facilitate security articulations. The fourth part discusses the visual politics-security of migration in relation to the Calais situation. The fifth part presents the methodology and in-depth analysis of two eyewitness videos from the Calais situation. In the final section, I discuss the key observations from the analysis and present the concluding arguments.

The role of non-elites in securitisation processes

The securitisation theory (ST)Footnote 20 developed by the Copenhagen School (CS) has been influential in analysing security through a constructivist lens. Drawing on John Austin's speech act theory,Footnote 21 ST conceptualises security as an illocutionary speech act. According to CS, securitisation constitutes a discourse of mediation, in which a securitising actor presents an issue as an existential threat to a referent object and mobilises support from an audience for measures beyond the realm of normal politics or procedures. Subsequent developments in ST have moved away from the overemphasis on speech act theory and adopted a sociological approach, which also places importance on the discourse of social practices, underlying context, cultural disposition, and power relations the speaker and audience bring about in constructing a security threat.Footnote 22 Contrary to securitisation, desecuritisation decouples a referent object from its security articulation. In a desecuritising move, the speaker or a range of actors dismiss the existence of a threat or argue that the threat can be easily addressed through the process of normal politics.Footnote 23 Though early scholars of securitisation,Footnote 24 especially CS, have advocated for desecuritisation, some have raised doubts about whether desecuritisation is desirable in every situation.Footnote 25

Furthermore, desecuritisation becomes difficult in settings of institutionalised securitisation. Constantinos AdamidesFootnote 26 describes institutionalised securitisation as ‘instances where the entire process of securitisation, including the referent objects, the source of threat, and the intersubjective process between actors and audiences, evolve into a state of permanency becoming inevitably part of the society's political and social routines’. The discourse of migration is an ideal example of an institutionalised securitisation, where the audience has been perpetually primed about the dangers the arrival of migrants and asylum seekers pose. The threat constitution of migrants is so firmly naturalised in such discourses that any attempts to desecuritise the representation of migrants is likely to face resistance. Such resistance or counter desecuritisation is not always necessarily a top-down elite-driven process but rather can also emerge from non-elite actors in the form of horizontal or bottom-up securitisations.Footnote 27

Although CS does not explicitly state that non-elites cannot securitise, the significant positional power and social capital needed to convince large audiences make elite actors likely candidates for securitising roles. The empirical literature on securitisation that has predominantly featured non-elites as audiences rather than securitising actors well exemplifies this.Footnote 28 Furthermore, the role of audiences is itself significantly under-theorised in ST and devoid of substantial agency.Footnote 29 However, AdamidesFootnote 30 claims that in certain instances of institutionalised securitisation, non-elites can also engage in a horizontal or a bottom-up securitisation, which does not entail the need to convince large audiences. For instance, in horizontal securitisation, sections of the non-elite audience act as securitising actors and attempt to influence their immediate peers to perceive an issue through already existing securitised logic.Footnote 31 In bottom-up processes, AdamidesFootnote 32 states that ‘the audiences either become securitising actors themselves or they apply so much pressure on the “mainstream” actors that the latter are “forced” to develop or perpetuate securitising acts even in cases where they do not necessarily feel strongly about it [the acts].’ Thus, in both horizontal and bottom-up processes, sections of the non-elite audience expect an issue to be addressed only through routinised securitisation processes and strongly oppose alternative desecuritisation attempts. AdamidesFootnote 33 states that the end goal of non-elites in horizontal and bottom-up securitisations is not to gain access to any kind of extraordinary measures but rather to remind peers or elite securitising actors about the existential threat and influence their behaviour in a way that can help to sustain the securitised environment. These non-elite driven securitising acts complement the top-down securitising process, making it more effective and routinised. Social media and visuals, especially eyewitness videos, provide further empowerment for non-elites to engage in these horizontal and bottom-up securitisations.

For actors with insignificant positional power, such as the non-elite members of the public, visuals have been a key artefact to engage in political action. Even before the era of personal cameras, marginalised sections of the public used visual representations in the form of posters as an act of resistance against unjust governmental laws.Footnote 34 The emergence of smartphones and social media further expanded and individualised public engagement in politics because the public could now document potential political events the news media did not cover. Without any active participation in protests, ordinary citizens can still engage in political action through the remediation of videos captured on their smartphones. Roland BleikerFootnote 35 calls this communication development as the ‘democratization of visual politics’ because mass media or political elites are no longer the sole gatekeepers in the production and distribution of images.

Though the visual is acknowledged as a key heuristic artefact that can bolster securitising moves, the empirical literature on securitisation has focused predominantly on written or spoken discourses,Footnote 36 which can be partly attributed to ST's emphasis on speech act theory. In her critique of ST's reliance on speech act theory, Lene HansenFootnote 37 argues that ST is unable to account for non-verbal performatives of security, such as the visual and the body. She advocates for the need to include the visual and the body as additional epistemological sites that can speak security without following the logic of the security speech act.

Visual politics and security: A literature review

With growing calls to take the role of visuals in IR and security studies seriously,Footnote 38 the past two decades have witnessed a visual turn in post-positivist IR and critical security studies. Many IR scholars have responded to this call by drawing on various interdisciplinary theoretical insights, methods, and empirical cases to study visuality in issues ranging from migration,Footnote 39 Islamic extremism,Footnote 40 war,Footnote 41 body,Footnote 42 and genderFootnote 43 to prisoner abuse.Footnote 44 Scholars within the post-positivist IR tradition dismiss the causal relation between visuals and subsequent policies or events and analyse how visuals discursively engage with existing discourses, narratives, practices, and texts to create ‘conditions of possibility’ for a subsequent policy, event, or decision.Footnote 45 The structuring of Roland Bleiker's influential edited volume – Visual Global Politics Footnote 46 – across 51 different political concepts, phenomena, themes, and issues exemplifies the growing relevance of visuals in politics and illustrates the theoretical and empirical diversity within the visual IR scholarship.

Visuality has also been a key topic of inquiry in the field of critical security studies. HansenFootnote 47 states that the security implications of visuals can be better analysed by asking ‘how images generate international conflicts and impact debates over national, religious, or other collective concepts of security’. The frameworks that Axel Heck and Gabi SchlagFootnote 48 and HansenFootnote 49 propose provide key methodological insights to analyse visual security. Heck and SchlagFootnote 50 adopt Panofsky's iconological approach to analyse the securitising power of images. They propose that ‘the ontological fixation on individual actors as the only securitising actors should be reconsidered’ as the symbolic power of images can speak security.Footnote 51 However, Hansen argues that visuals cannot securitise on their own because they need words or spoken discourses to articulate security.Footnote 52 To theorise the specificity of visuals, Hansen presents an intervisual/intertextual modelFootnote 53 consisting of four components: the visual itself, its immediate intertextual context, the wider policy discourse, and the constitutions of the image.

According to Hansen,Footnote 54 ‘visual securitizations differ from exclusively linguistic ones in that the image accentuates immediacy, circulability, and ambiguity’. Immediacy refers to the sense of closeness with an event or object a medium evokes. Visual immediacy evokes emotions of shock and fear, which are closely associated with a sense of insecurity. These emotions do not articulate a clear threat or a definite policy, but they can engender conditions of possibility for a particular narrative or course of action.Footnote 55 Compared to words, visuals project a stronger sense of immediacy and circulability. The differences in their semiotic structures account for differences in the circulability and impact of their immediacy. Rune Andersen et al.Footnote 56 state that ‘linguistic texts tend to unfold their meaning progressively along syntagmatic chains, while the whole of a visual image tends to be perceived before its individual parts.’ This means that visuals have a wider audience reach than words, although the interpretation of a visual may differ with different audiences.

A visual's meaning is ambiguous because it can have multiple interpretations based on the audience's cultural, social, political, and geographical contexts. HansenFootnote 57 claims that the ambiguity of visuals can allow multiple actors to ‘constitute themselves as capable of speaking security’. For visual securitisation, the depictions within a visual need to be constituted through a particular security discourse, which can happen using textual forms. In the context of politics and news events, it is extremely rare to encounter a visual in isolation. There is always an accompanying text in the form of a commentary, headline, or caption hovering nearby. Roland BarthesFootnote 58 compares these textual components to a parasite that clings to the visual and thrusts its own meaning upon the visual. Even though written or spoken words constantly accompany the visual, the ambiguity surrounding a visual's meaning can also drive the viewer towards the immediate intertext. W. J. Thomas MitchellFootnote 59 argues that viewers have been disciplined and conditioned to decode a visual by means of textual forms, which provides them with certainty and closure. Even a single word in the accompanying text has the potential to influence and dominate the interpretation of the viewer.Footnote 60 For example, the use of either ‘refugees’ or ‘illegal immigrants’ as a term to describe the characters in a visual has different sociopolitical connotations. These terms create multiple intertextual references, thereby influencing a viewer's interpretation.Footnote 61

Politicising and securitising factors in the communication of eyewitness videos

Though the theoretical insights outlined in the visual securitisation framework are significant, security articulations facilitated by the specificity of a genre also need to be accounted for. Visual genres can differ in the way they evoke (in)security. HansenFootnote 62 calls for variations to her framework that can account for politicising and securitising elements that are visible in other genres. The increasing regularity of eyewitness videos used as a source of information in political and security discussions raises the question of how (in)security is constituted through eyewitness videos. Drawing from Hansen's framework, I argue that two factors of eyewitness videos play a key role in shaping political and security articulations – epistemic-political constitution of eyewitness videos and the online remediation of eyewitness videos through the complex networked act between calculated security publics and video recommendation algorithms of social media.

Epistemic-political constitution of eyewitness videos

For Hansen,Footnote 63 ‘The epistemic-political constitution of the visual concerns, first, the kind of claim the visual makes about its relationship to “the real”.’ Different genres make different forms of epistemic-political claims and generate different audience expectations.Footnote 64 The genre of press photography, for instance, claims to accurately depict reality, whereas the genre of cartooning projects a sense of reality through satire. Similar to press photography, eyewitness videos are also perceived to be authentic depictions of an event.Footnote 65 News media also acknowledge the epistemic authority of eyewitness videos as they regularly reuse eyewitness videos to report on natural calamities, conflict zones, and other news events, where journalists were not available.Footnote 66 However, the deemed authentic value of eyewitness videos is shaped by several factors, which I will discuss here: eyewitnessing, anonymity of the eyewitness, and amateur aesthetics. These factors play a key role in constructing the truth claim of eyewitness videos, which facilitates security articulations.

Eyewitness videos have brought in a new sense of closeness with a depicted situation. The event or the scene captured in eyewitness videos signifies the proximity of an ordinary citizen with the event, as the eyewitness footage of natural calamities, protests, and conflict zones in the last decade demonstrates. The eyewitness is a regular figure in news media reporting practices, who is entrusted with the authentic retelling of the event. Tamar Ashuri and Amit PinchevskiFootnote 67 claim that ‘one qualifies as a witness predominantly by virtue of being present at the event.’ Thus, by just being on the site, the eyewitness gains authority over the authenticity of the event's story. Barbie ZelizerFootnote 68 describes eyewitnessing as the ‘ability to account subjectively for the events, actions, or practices seen with one's own eyes’. Eyewitness accounts have been traditionally perceived as authentic, even though they are vulnerable to inaccuracies, distortions, and unreliability.Footnote 69 In the context of media witnessing, the agency of firsthand eyewitnesses has changed significantly. The eyewitnesses of an event are no longer completely dependent on news media to broadcast their stories. They now possess the resources to visually document and share their experience with mass audiences without the gatekeeping of news media.Footnote 70 The realism associated with narrative accounts of eyewitnesses is now transformed into audio-visual forms. With the help of social media, eyewitnesses also have the freedom to choose the political discourse through which they want to present the event.

The anonymity of most eyewitnesses also facilitates the truth claim of eyewitness videos. Anonymity gives a sense of neutrality to the presentation of an event because the audience is unfamiliar with the political subjectivities of the eyewitness picture producer. However, the sense of neutrality associated with the eyewitness is contingent on the eyewitness's level of participation in the event. Mette MortensenFootnote 71 states that there is a certain degree of ambivalence between documentation and participation. Some eyewitnesses assume a passive bystander role while documenting an event, such as in the footage depicting the death of Neda Aghan-Soltan during the 2009 post-election protests in Iran. In contrast, active participants engage with the event and make it known to the audience where they stand regarding the situation. Some examples include the killing of Gaddafi, where men posed with a victory sign around the dead leader's head; the Christchurch shootings; and Elin Ersson's livestreaming attempt to halt the deportation of an asylum seeker from Sweden.Footnote 72 Passive participation of the eyewitness allows a wide range of actors to recontextualise the meaning of the event through preferred political and security framings. However, passive participation does not necessarily imply that the eyewitness is not politically invested in the documentation of the event.Footnote 73 It might be recognisable in less subtle ways, but the audience is less likely to be aware of it.

The amateurish aesthetics of eyewitness videos, such as grainy quality, shaky camera, and poor editing skills are often perceived as a trademark of authenticity and proximity to an event.Footnote 74 For a non-professional viewer, eyewitness videos with poor quality evoke a sense of familiarity because they create a feeling that someone like the viewer with similar positional power captured the event. Additionally, the circulation of graphic imagery facilitates the immediacy and authenticity of eyewitness videos. The ethics of journalism do not restrict eyewitness picture producers, who therefore are free to share pictures depicting strong violence or dead bodies. The graphic nature of images makes the content immediate and shocking, but it also triggers strong emotional responses and stimulates insecurity.Footnote 75 The inability to ascertain what is sharable or not makes eyewitness picture producers easily identifiable as non-professionals, but the practice of broadcasting an event in its crude and unedited form also accords a sense of authenticity upon the eyewitness videos of the event.

In addition to being a witness, an eyewitness picture producer is more likely to document and share something on the Internet if the situation seems irregular, unique, or hostile.Footnote 76 Thus, eyewitness videos that enter political debates often depict something that is nonconforming with social and political norms. The non-conformity of a situation is often newsworthy for an eyewitness picture producer. In fact, the gesture of raising the smartphone camera to capture something is a non-verbal performative act because it implies to other participants at the event that the moment is significant enough to be captured.Footnote 77 Therefore, the audience also generally expects that the content of an eyewitness video will be captivating, engaging, or shocking.Footnote 78 For the audience, the content of an eyewitness video thus constitutes an epistemic truth about unconventionality and sensationalism.

Security articulations during online remediation of eyewitness videos

The technological and social modalities of social media communication play a closely entangled role in facilitating the online remediation of security articulations around a visual.Footnote 79 The recommendation algorithms of social media present content to users that corresponds to their browsing history.Footnote 80 This creates an echo chamber, where the audience is intentionally or unintentionally manoeuvred into following content with a monolithic perspective that keeps reaffirming their pre-existing views. The algorithms create what Tarleton GillespieFootnote 81 calls ‘calculated publics’, who are brought together because of their similar social and political opinions. In the context of security, such calculated publics or, to use Andersen's term,Footnote 82 ‘calculated security publics’ can constitute a visual's meaning through routinised or institutionalised security discourses. AndersenFootnote 83 states that ‘video platforms based on the algorithmic knowledge logics of machine learning, automated calculation and spreadability’ assume an editorial role by determining the newsworthiness of a video. This means that political importance and news value are accorded to visuals with higher engagement metrics, such as number of views, shares, and comments irrespective of the severity represented in the visual.Footnote 84

Eyewitness visuals posted on social media enter security debates through this technology-powered remediation. In describing the networks of mediation, Lilie Chouliaraki and Myria GeorgiouFootnote 85 define remediation as the ‘vertical mobility of social media content shifting onto mass media platforms’. This mobility is vital for the security articulation of eyewitness videos because a news media reference is an acknowledgement of the video's virality and newsworthiness. In fact, AndersenFootnote 86 defines virality as the ‘keyword that describes successful remediation’. Even though social media provides a participation platform for the public to contextualise a visual's meaning, certain articulations surrounding a visual become more dominant than others because of the authority and social position of the disseminator.Footnote 87 During the remediation of eyewitness videos from social media to mass media, a complex network of actors with varying degrees of positional power, such as non-elite users, social media influencers, celebrities, politicians, and mass media professionals, recontextualise its security articulation. The higher the positional power of the remediating actor, the faster videos enter security debates.Footnote 88 Thus, a complex networked act between the ‘calculated security publics’ and technological aspects, such as the recommendation algorithms of social media platforms, constitutes the agency in articulating security through eyewitness videos.Footnote 89 This complex network plays a gatekeeping role because it can determine which eyewitness video among the vast number of videos on the Internet will engage with the political discourses in place. Therefore, tracing and analysing the remediation activities of an eyewitness video is fundamental to understanding its primary security articulation before studying securitisation through institutionalised voices and practices. Such an analysis will also help understand to what extent the online network of actors draws from institutionalised security discourses while remediating the visual.

Visual securitisation of Calais asylum seekers

Contemporary visual representations of refugees in Western societies drive the visual politics of the Calais situation in the UK.Footnote 90 The collective understanding of refugees in Western societies has evolved considerably in the three decades since the fall of the Soviet Union.Footnote 91 In contemporary political communication, the ‘refugee’ is rarely associated with qualities such as bravery or fearlessness.Footnote 92 Rather, the present-day refugee in Western news media is seen either as a desperate body in need of Western help or as a threat to Western societies.Footnote 93 These polarising discourses of humanitarian responsibility versus threat have dominated discussions related to refugees and played a significant role in the visual politicisation and mediatisation of the European refugee crisis and the Calais situation.

The sociopolitical meanings attached to refugees and asylum seekers during the European refugee crisis place the Calais issue within a larger political debate. On the one end of the political spectrum is the politics of pity,Footnote 94 where NGOs and humanitarian organisations represent asylum seekers as helpless victims, who can be helped only through Western agencies. Two visual tropes are often employed within this discourse: massification and passivisation.Footnote 95 The massification representation depicts asylum seekers in large groups or camps, whereas the passivisation representation strives to evoke compassion among its audience by highlighting the vulnerability of asylum seekers using depictions of women, children, poverty, and hunger.Footnote 96 NGOs and human rights organisations often use these representations to mobilise public support towards the cause of asylum seekers.Footnote 97 In Calais, humanitarian organisations and media outlets have regularly employed these tropes by depicting Calais asylum seekers as helpless people fleeing war, poverty, and persecution, who are forced to live in dangerous and inhuman conditions in the Calais jungle.Footnote 98 However, Lilie Chouliaraki and Tijana StolicFootnote 99 state that both these visual tropes dehumanise asylum seekers even though they have humanistic intentions. The lack of asylum-seeker-produced visuals in the political debates of Western media signifies that asylum seekers are stripped of their agencies and voices.Footnote 100 In Calais, though asylum seekers often captured videos about their conditions, these videos rarely made it to the mainstream media.

Surprisingly, it is the threat discourse that attributes some agency to asylum seekers. However, the politics of fear significantly influence the representations within this agency, where asylum seekers can be easily constituted as threatening.Footnote 101 A strong sense of othering fuels this discourse, where asylum seekers such as those in Calais are seen as illegal migrants who pose a security threat to the UK or, in a broader sense, to European/Christian civilisation. During the European refugee crisis, there was a growing sense of resentment among many sections of the European public over the pro-refugee discourses and decisions adopted by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the leaders of other EU states. Right-wing populist parties across Europe exploited this resentment, securitising the influx of asylum seekers as an existential threat to European civilisation. To promote this securitising move, politicians, right-wing media, and social media users engaged in politics of fear as they mobilised and disseminated many anti-refugee narratives. The prominent ones being, ‘Muslim culture is incompatible with European civilization’, ‘Influx of refugees is part of a Muslim invasion’, ‘They are not refugees fleeing war but economic migrants’, ‘There are no women and children among refugees but only able-bodied men’, ‘ISIS is sending terrorists into Europe disguised as refugees’, and ‘Refugees are only interested in welfare money’.Footnote 102 These narratives further amplified the construction of Calais asylum seekers as a security threat.

Within the threat discourse, there is less ambiguity over the visual dehumanisation of asylum seekers. The most prevalent visualities of perceived threats during the European refugee crisis were large groups of young men engaged in protests and riots; processions of asylum seekers crossing EU borders and walking along the streets of Europe; and boats filled with asylum seekers disembarking at European islands, beaches, and ports.Footnote 103 The ubiquity of border fences, police cordons, bulldozers, tear gas, and shields characterises the visuals depicting asylum seekers. Chouliaraki and StolicFootnote 104 call these elements ‘demarcating devices’ that segregate asylum seekers from the host population and further amplify the sense of othering. Fences and police officers serve as symbolic settings that create a visual distinction between the legal and the illegal. Their presence articulates (in)security because it indicates a precautionary measure against a threat. VuoriFootnote 105 argues that the use of symbolic settings in a visual can complement a securitising move. For nation-states, a border fence serves as a symbolic setting that cannot be violated. Any violation of this setting signifies a violation of the sovereignty of the nation-state, which is already constituted as a referent object in security debates. Calais, being a border town, serves as a symbolic setting for the securitisation of migrants and asylum seekers. News media and politicians have played a pivotal role in shaping visual representations of migrants and asylum seekers.Footnote 106 In their study on the visual representations of asylum seekers in Australian media, Bleiker et al.Footnote 107 state that the lack of close-up portrayals and recognisable facial features of asylum seekers facilitates politics of fear. During the European refugee crisis, news media and politicians often employed dehumanising designations, such as ‘swarms’, ‘tides’, ‘illegals’, and ‘flow’ that further anchored the security articulations of asylum seekers.Footnote 108 In Calais, the visualities of threat constituted scenes of people walking/running on the highway, slums/camps, bulldozers, police officers, people threatening truck drivers, and people climbing onto the backs of trucks.Footnote 109

The ‘us’ vs ‘them’ rhetoric is dominant in debates surrounding the issue of refugees in Europe, but Chouliaraki and ZaborowskiFootnote 110 argue that there is ‘a further division within “us”’. Compared to NGOs and activists, the voice and agency of non-elite European citizens are significantly underrepresented in news media stories related to refugees. Similar to asylum seekers, the host population is often spoken about or spoken for by politicians, news media, or activists, according to whom ‘refugees are a threat’ or ‘it is our moral responsibility as European citizens to help refugees.’ The voice of the host population regarding the refugee situation gets subsumed under the threat narrative of right-wing populists or ignored among the voices of humanitarian activists. However, the advent of social media and smartphones has significantly enhanced the agency of non-elites in political communication and securitisation processes. As eyewitness videos captured by host populations feature increasingly in refugee news stories, the voices of the non-elite ‘us’ has received more political coverage. Sections of non-elites from the host population have often used social media and eyewitness videos to counter desecuritisation attempts by NGO groups, activists, news media, and politicians, who tried to shift the issue of asylum seekers away from the security rhetoric. For instance, the events in CologneFootnote 111 and SwedenFootnote 112 triggered significant outrage from many sections of the society after attempts were initially made to downplay the violent sexual acts asylum seekers committed. Eyewitness videos are useful resources to understand how the non-elite ‘us’ perceives the refugee situation, how they represent asylum seekers, to what extent mainstream discourses of refugees influence this representation, and more important for the purpose of this study, how these videos contribute to political-security debates about refugees and asylum seekers. The Calais situation serves as an excellent case study to explore these questions.

The inability of the French and UK governments to resolve the Calais situation since 1999 has been a source of frustration among truck drivers and residents of Calais. As asylum seekers persistently attempt to cross into the UK, a recurrent pattern of events characterises the Calais situation – emergence of refugee camps, attacks on truck drivers and local residents, demolition of camps by French authorities, and the re-emergence of the camps.Footnote 113 The constant presence of the perceived threat asylum seekers pose has routinised and institutionalised the security articulations and policies in Calais. Within such institutionalised securitisations, the government does not need much dramatisation to convince audiences about security measures.Footnote 114 On the contrary, local residents and truck drivers often pressured the government to adopt strict security measures to address the threat of asylum seekers. With the emergence of smartphones and social media, truck drivers started sharing their dashcam footage on YouTube and other social media platforms that showed asylum seekers attacking their trucks along the highways. Some of these videos attracted news media coverage and facilitated further securitisation of Calais asylum seekers through the threat discourses prevalent during the European refugee crisis.

Methodology and analysis

Methodology

The eyewitness videos analysed in this study were constantly used to stimulate debates and portray the Calais asylum seekers as a security threat. These videos evidently represent a narrow part of a much wider context of the Calais situation. The problem of whether these videos are representative of the overall discourse of the Calais situation is not very significant for this analysis because the study's primary purpose is to analyse how eyewitness videos facilitate political and security articulations of asylum seekers. Therefore, the videos for this analysis were chosen through purposive sampling using the following criteria: (a) popularity – the video had a high number of views and was often a topic of discussion or was referred to in mainstream media and on social media channels; and (b) intertextuality – the video was often used as an intertextual reference to portray Calais asylum seekers as a security threat. To search videos for this analysis, a Google searchFootnote 115 for the terms ‘Calais’, ‘Calais refugees’, ‘Calais migrants’, ‘migrants’, refugees’, and ‘Calais truck drivers’ was conducted for the time frame between January 2014 and December 2016, when the European refugee crisis was at its peak. During this period, there was a heightened sense of urgency around the topic of asylum seekers, and videos that portrayed asylum seekers through visualities of threat had a higher securitising potential.

This study aims to explore the politicising aspects of eyewitness videos across different sites and modalities of communication. The theoretical insights presented in the earlier sections span across the production, visual, circulation, and audiencing sites of visual communication.Footnote 116 Analysing eyewitness videos along the technological, social, and compositional aspects of these sites of communication requires an in-depth approach consisting of multiple methods. Therefore, only two eyewitness videos could be accommodated in this analysis. The first visual was an eyewitness video a traveller, Jenny Adams, uploaded on 8 June 2015. The video attracted more than a million views and received mainstream media coverage. The second visual was a dashcam video a Hungarian truck driver, Arpad Levente Jeddi, shared on 25 November 2015. Despite being in Hungarian, Jeddi's video was the most viral among all eyewitness videos on the Internet related to the Calais situation. It triggered significant public discussion on social media communities and was featured on several English news media channels.

Discourse analysis was the primary method of analysis used to uncover the traces of political-security articulations along the video's sites of meaning-making. Additionally, computational content analysisFootnote 117 was conducted on the comments section of particular social media sites to determine how the audience interpreted the recontextualisation of the visual's meaning and the representation of asylum seekers.

Analysis of visual 1

On 8 June 2015, Jenny NZ uploaded a videoFootnote 118 on YouTube that depicted large groups of asylum seekers breaking into trucks. At the time of writing, the eyewitness video had garnered around 1.8 million views on YouTube. Because the video was haphazardly captured from inside a tourist bus, it creates a sense of authenticity and familiarisation with viewers, who have a similar viewing perspective of the road while travelling. The video is titled, ‘Rioting Migrants Yesterday – Calais to Dover Port’. The term ‘migrants’ establishes the identity of the represented participants. Whereas ‘rioting’ stimulates fear, ‘yesterday’ generates a sense of urgency around the situation in Calais. The video starts with a large number of asylum seekers walking on the highway and climbing on to a truck in front of the bus. The context of the situation is gradually built through the dialogues in the video. The first voice seems to be of the tourist bus guide, who says, ‘They are not allowed in the country’, which creates a sense of segregation between ‘us’ and ‘them’. It also reinforces the Calais asylum seeker as a demonising ‘Other’, who is significantly excluded from the ‘Self’ and needs to be feared. The phrases that follow, such as ‘Don't panic, I have locked all the doors’, ‘Holy Moly’, and ‘We saw this on TV’ stimulates emotions of fear and shock. As the video progresses, more asylum seekers appear on the road, and the bus guide again instructs the tourists not to panic. The scenes of a large number of asylum seekers and the apprehensive dialogues in the video work together to stimulate tension and create an impression that the asylum seekers will imminently attack the tourists. It also builds on the demonising and othering references of the migrants and asylum seekers.

To analyse the initial remediation of Jenny's video, we need to look at the responses and activities surrounding the video since its publication. Jenny shared her video on YouTube on 8 June 2015, and by 15 June 2015, it was featured in mainstream UK media. A Google search for related keywords, such as ‘Rioting migrants Calais’, ‘Calais’, ‘Calais tourist bus’, ‘Jenny Calais’, ‘Calais refugees’, and ‘Calais migrants’ between 8 June 2015 and 15 June 2015 showed how different actors responded to, interpreted, and recontextualised Jenny's video.

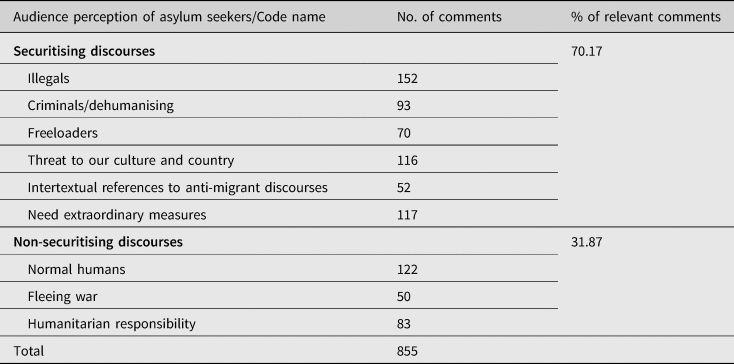

On social media, the video was first discussed on Reddit among the members of a community (also known as a subreddit), r/videos, on 14 June 2015.Footnote 120. Reddit is a forum website where users form or join communities based on personal interests and post related content in the form of links, texts, images, and videos within these communities. The community members of r/videos share interesting videos they encounter online. At the time of writing, Reddit was the 18th most popular website in the world,Footnote 121 and the r/videos community had 20.4 million members. A content analysis of the comments section showed that a vast majority of the commentators viewed the asylum seekers through the threat discourse. They referred to the asylum seekers using terms such as ‘illegals’, ‘criminals’, and ‘freeloaders’. Tables 1 and 2 show the coding schema and results of this analysis. The commentators predominantly perceived the asylum seekers as a threat and espoused extraordinary measures to address the Calais situation.

Table 1. Coding schema as per the dominant perception among Reddit commentators.

Table 2. Reddit comments by description of asylum seekers and interpretation of visual.

On 15 June 2015, the video was featured in the UK's mainstream news media, such as the Daily Mail,Footnote 122 Sky News,Footnote 123 and the Telegraph.Footnote 124 Even though other mass media outlets consider the Daily Mail unreliable,Footnote 125 it is still the most widely read print newspaper and the second-most read digital newspaper in the UK.Footnote 126 Sensationalism and fearmongering are typical characteristics of the Daily Mail's narrative style, and it often attempts to shock readers through the titles of its reports. In fact, the Daily Mail's titles are the most widely read news titles in the UK.Footnote 127 To report the incident captured in Jenny's video, the Daily Mail used a five-line title followed by four key points (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of the headline the Daily Mail used to describe Jenny's video.

The title and key points portray the situation in Calais as alarming and lawless. In line with its characteristic narrative style, the Daily Mail provided a detailed account of the video through the securitised discourse of the Calais asylum seekers. In the following days, the Daily Mail used the video and screenshots from the video in four of its reports related to the Calais situation.Footnote 128 The video and the screenshots were presented as visual evidence of the dangerous situation in Calais. The video also evoked a response from Charlie Elphicke, the Conservative MP for Dover, who used it to illustrate the deteriorating security situation in Calais.Footnote 129

Analysis of visual 2

On 25 November 2015, Jeddi uploaded a video on YouTube documenting his journey towards the Calais port. The original video link on YouTube is not available anymore, but other social media users have uploaded the video. Because of the offensive language and provocative actions of Jeddi, YouTube has removed the video and many of its mirror versions for violating its hate speech policy. At the time of writing, the entire content of the video can be viewed through one of its mirror versions.Footnote 130 The video includes some shocking scenes of asylum seekers trying to break into trucks and Jeddi swerving dangerously towards the asylum seekers. Even though the video was in Hungarian, it quickly went viral on social media. Before it was taken off YouTube, it had garnered around 4.4 million views.

Jeddi used a dashcam to record the video. Drivers use dashcams to keep digital evidence of their drives.Footnote 131 The video footage proves useful for drivers to claim insurance after accidents and for exposing fraudsters trying to extract money after a false crash. Dashcam footage are usually shared on the Internet when they capture something newsworthy or irregular.Footnote 132 Thus, a viewer who watches dashcam footage on the Internet expects to see something unusual or shocking. This conventionalised audience expectation associated with the genre of dashcams adds to the immediacy factor in Jeddi's video.

The original video was titled, ‘Calais Emigrant vs Drivers and EUROPA’. The title makes a clear reference to the Calais migrant situation. The use of ‘vs’ in the title creates a sense of othering. By using the term ‘Drivers and Europa’, Jeddi indicates how he views the asylum seekers: not just as a threat to himself or other drivers, but as a threat to Europe. The identity of the Calais asylum seekers as the ‘Other’ was already established in the title and is further reinforced as Jeddi utters the word, ‘Immigrante’. As more people appear walking on the road, they are now seen through the frame of ‘migrants’ or ‘Calais migrants’. The depictions of asylum seekers in Jeddi's video follow the dominant visualities of threat and insecurity, such as ‘large groups’, ‘people trying to climb onto the back of trucks’, ‘fences’, and ‘the presence of police officers’. The gestures of Jeddi and the asylum seekers in the video also play a critical role in creating a sense of immediacy and fear. There are multiple instances of asylum seekers throwing or pretending to throw objects at Jeddi's truck. These violent acts criminalise the asylum seekers and mobilise fear.Footnote 133 In response to these actions, Jeddi dangerously swerves the truck towards the asylum seekers. Even though Jeddi attempts to politicise the Calais asylum seekers through the discourse of threat, he needs social media users and actors with significant positional power to acknowledge, publicise, and amplify his articulation.

Jeddi shared his video on YouTube on 25 November 2015, and by 28 November 2015, it was a topic of discussion on mainstream media. A Google search for the terms, ‘Hungarian driver Calais’, ‘Calais’, ‘Calais truck driver’, ‘Jeddi Calais’, ‘Calais refugees’, and ‘Calais migrants’ between 25 November 2015 and 28 November 2015 helped track how Jeddi's video was remediated, interpreted, and recontextualised online. The day after its publication, Jeddi's video expanded its audience reach when it was shared on Reddit's community, r/Roadcam. The community members of r/Roadcam share and discuss shocking road videos usually captured from dashcams. At the time of writing, the community had two million subscribers.Footnote 134 Jeddi's constitution of Calais asylum seekers as a security threat was further consolidated when Breitbart, a far-right news website, published a detailed report the next day describing the events of the video.Footnote 135 Breitbart is known to present news that often tends to be sensational, migrant-sceptic, and fake.Footnote 136 Its report on Jeddi's video maintains the same pattern. The report translates some of Jeddi's comments directed at the asylum seekers, calling them freeloading migrants, all-male refugees, and ISIS terrorists. By translating Jeddi's comments, Breitbart made the video comprehensible for its English-speaking readers but through a securitised narrative.

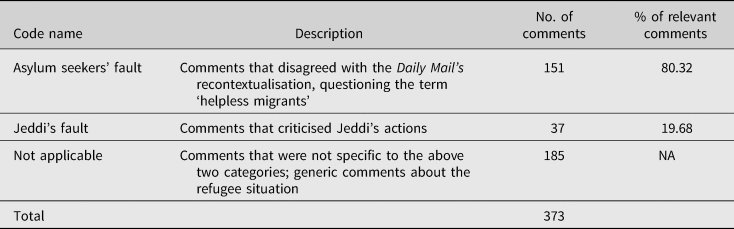

As Jeddi's video generated significant interest and discussion on social media, it started to attract mainstream media's attention. On 28 November, The Daily Mail published a report detailing the events depicted in Jeddi's video.Footnote 137 The title of the report used the term ‘helpless migrants’, which was rather unusual considering the Daily Mail's reputation for demonising asylum seekers and promoting anti-immigration and anti-refugee rhetoric. The report used only one specific clip from Jeddi's video, which showed him swerving towards the asylum seekers and excluded other parts of the video depicting the asylum seekers’ provocative behaviour. The accompanying report complemented the selective footage, highlighting the threat Calais asylum seekers face from drivers such as Jeddi. However, the Daily Mail's recontextualisation of the video did not seem to resonate with its audience. A computational content analysisFootnote 138 of its Facebook postFootnote 139 on the same article showed that most commentators disagreed with the narrative The Daily Mail propagated (Table 3).

Table 3. Content analysis of comments from the Daily Mail's Facebook post.

By 30 November 2015, other UK mainstream media channels, such as The Guardian,Footnote 140 Channel 4 News,Footnote 141 and the Independent,Footnote 142 had picked up Jeddi's video. They also used the same cropped footage of Jeddi swerving at asylum seekers. By downplaying the violence the asylum seekers committed, these media reports attempted to desecuritise the threat of Calais asylum seekers. Instead, they counter-securitisedFootnote 143 it by presenting the safety of asylum seekers as a referent object and constituting Jeddi and truck drivers as a security threat. Whereas Jeddi's video was remediated with securitised and desecuritised articulations by various actors, the cropped footage of Jeddi swerving towards asylum seekers became an iconic gesture in the context of the Calais situation. News mediaFootnote 144 and user-generated montagesFootnote 145 regularly used it to illustrate the alarming situation in Calais.

Discussion and conclusion

One of the key factors that facilitated the threat constitution of Calais asylum seekers was the largely accepted meanings of (in)security associated with the depictions of violence and confrontation that featured in both videos. The depictions of asylum seekers in both videos served as visual confirmation of some of the narratives within the anti-refugee discourse. For example, the predominant presence of male asylum seekers in both videos attested the ‘all-male’ narrative. Similarly, the scenes of people running on a highway, breaking into trucks, threatening drivers, and throwing objects onto the trucks made intervisual references with traditional depictions of chaos and anarchy. Neither video had any visual aspects that could be described as Islamic. However, Jeddi's commentary and the subsequent remediation of the videos characterised the actions of the asylum seekers as an Islamic invasion. The dominant visualities of the ‘malevolent refugee’ in both the videos strongly contradicted and discredited the visual discourse of the ‘helpless refugee’. Except Jeddi's swerving act towards the asylum seekers, the videos did not contain any moments where the asylum seekers could be constituted as vulnerable or as victims. Instead, the asylum seekers were clearly seen as threatening, and their actions evoked emotions of fear and anger, which facilitated the use of politically incorrect language by many social media users.

The commentators under the videos on social media platforms played a key role in mobilising the securitising discourses of Calais asylum seekers. Many commentators used strong language to describe the asylum seekers and suggested radical measures such as ‘shoot to kill’ and ‘run them over’ to address the situation. Such ‘calculated security public’ does not need to be convinced of the securityness of the situation.Footnote 146 The asylum seekers were often described as illegals, invaders, scums, parasites, freeloaders, ISIS terrorists, and criminals who would destroy Western/European culture. The use of politically incorrect language to securitise adds new uninhibited dimensions to security articulations of migration that would be inconceivable in top-down securitisation processes. Thus, even though non-elites do not possess the authority to implement security measures, they can still play an influential role in securitisation by convincing their peers about a threat through a dehumanising vocabulary that is almost impossible for elite securitising actors to use. For instance, one of the comments under the Daily Mail's Facebook post of Jeddi's video stated, ‘Two years from now Europe will be a colony of Invaders.’ An elite securitising actor would be unable to utter these words to securitise the threat of migrants and asylum seekers without facing significant political repercussions. However, the ethics of journalism do not bind non-elites on social media, and neither do they have to face political backlash for their comments. Rather, the insignificant positional power of non-elite users on social media allows them to securitise the Calais situation through an ‘unconventional security grammar’ that audiences rarely hear from elite securitising actors.Footnote 147 The security articulation of Calais asylum seekers through such a strong language may be dehumanising and politically incorrect, but it can be emotionally persuasive and convincing for some audiences. The ubiquity of these comments on social media platforms meant that the dominant interpretation of Jenny and Jeddi's videos was easily accessible and intelligible to a wide audience.

The two picture producers had contrasting levels of participation. Jenny maintained a passive participation (even though it is not very clear whether the female voice in the video belonged to her), which meant her personal views about the situation remained ambiguous for viewers. Her apparent anonymity brought about a sense of neutrality and strengthened her eyewitness authority. On the contrary, Jeddi was an active participant and had a clear preconceived securitising intent. He did not shy away from expressing his opinions on the issue and presented the situation through the security discourse of an immigration/refugee threat.

Jeddi's extreme gesture of swerving the truck towards the asylum seekers also non-verbally signified his approval for extraordinary measures to address the threat of Calais asylum seekers. The audience's cultural and geographical diversity on social media was hardly an impediment for the securitisation of Calais asylum seekers. Jeddi's Hungarian video demonstrated that the remediation of eyewitness videos can transgress linguistic barriers on social media without losing their securitising context.

Although both videos had alarming visual aspects, they depended on the textual components and remediation of the networked online communities to articulate security. The network of social media users, news media, and politicians played a vital role in remediating the videos with security articulations and expanding its audience reach. Even though mainstream media has generally shied away from using eyewitness visualsFootnote 148 as a news source, media outlets such as the Daily Mail and Russia Today have embraced eyewitness videos in their news coverage. The Daily Mail covered in detail both the visuals analysed here before they were picked up by other mainstream news media such as the BBC, Guardian, and Independent. The empirical analysis showed that social media platforms such as Reddit can generate significant public discussion around eyewitness videos to facilitate their virality, making it difficult for news media to ignore them. The communities of Reddit serve as the first bridge between eyewitness videos and mainstream media because they play a key role in scouting obscure eyewitness videos for the Daily Mail. Because the analysis was primarily concerned with how the eyewitness videos propagated the threatening discourses of Calais asylum seekers, the network of online actors identified in the analysis is specific to the discourse that perceives Calais asylum seekers as a security threat and therefore cannot be generalised. This communication network will likely constitute a different set of actors if a video depicting the vulnerability of asylum seekers is remediated through a humanitarian narrative. Although Calais asylum seekers also produced and shared videos about their conditions and journey, their videos did not get enough traction because they lacked a network of online remediation actors who could amplify their voices and perspectives.

This study set out to examine how the genre of eyewitness videos presents new political-security implications for the issues of migration and refugees. Two factors – epistemic-political constitution of eyewitness videos and its subsequent online remediation – play a key role in constituting asylum seekers through a securitised discourse. With eyewitness videos contributing to the increased visual documentation of violent acts asylum seekers commit, the perception of refugees becomes more centred on malevolence and criminality. Most viral eyewitness videos captured by non-elites in Calais depict asylum seekers in violent and confrontational acts. Non-elites on social media also played an influential role in remediating these videos through security articulations. The remediation contributed to the increased visibility of these videos on social media networks, making it difficult for the news media and politicians to ignore. The remediation also demonstrated a strong resistance to the desecuritisation of Calais asylum seekers. The violence asylum seekers committed necessitates political discussion. Downplaying the hostility of asylum seekers or dismissing the eyewitness videos that depict these acts without situating them within the realm of normal politics will only lead to stronger legitimisation of securitising acts and measures. This is one of the drawbacks of desecuritisation, as Thierry Balzacq et al.Footnote 149 point out: ‘desecuritizing an issue has the effect of downplaying its importance or urgency, which may also have negative effects in certain situations.’ The increasing popularity and acceptance of eyewitness videos as news sources means that desecuritisation of the migration threat discourse will remain one of the biggest challenges for policymakers, news media, the public, and the academia. This also raises the question as to whether desecuritisation is really an effective strategy for an institutionalised securitisation issue such as migration. In some securitisation cases, as Paul RoeFootnote 150 suggests, ‘“managing” securitized issues might be more profitable than trying to “transform” them.’

In addition to being an empirical contribution to the visual IR literature, this article also highlighted how eyewitness videos and social media enhance the securitising potential of non-elites. However, this study has certain limitations and presents several opportunities for future research. The fact that only two videos were analysed means that the observations of this study cannot be generalised widely. The remediation of eyewitness videos was analysed using a basic Google search and could have been made more precise with the use of digital methods and data mining. However, the exploratory nature of this study meant that the focus was more on gaining a broader understanding of a relatively unexplored phenomenon rather than on generalisability and precision. Research on eyewitness videos is still relatively at a nascent stage and requires further conceptualisation to unpack its visuality. Future research could accommodate more videos for analysis by systematically focusing on one specific site of communication, such as production, visual, circulation, or audiencing. Another line of research could also shed more light on the factors that determine the framing of and news value criteria for eyewitness picture producers through interviews of picture producers and viewers.

Acknowledgements

This article was adapted from my Master's thesis developed at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, University of Tartu, Estonia. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and encouraging feedback, and the EJIS's editors for providing me the time and space to improve the article. I would like to thank Viacheslav Morozov, Elizaveta Gaufman, and Jacek Kołodziej for their invaluable insights on the topic of this article.

Funding

The proofreading fee of the publication was funded by the Priority Research Area Society of the Future under the programme ‘Excellence Initiative – Research University’ at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

Vaibhava Shetty is a PhD student in Social Communication and Media at the Jagiellonian University, Poland. His research interests centre on media communication and visual politics, with particular focus on eyewitness videos and their implications on the issues of refugees and migration.