Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity have clear short-term effects, being associated with higher risk of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, premature birth, caesarean section and large-for-gestational-age offspring(Reference Patel, Pasupathy and Poston1). In the long-term, it has been reported that offspring of overweight mothers have a higher risk of abdominal obesity, higher BMI, fat mass percentage and lower lean mass(Reference Stephenson, Heslehurst and Hall2–Reference Galliano and Bellver4). Furthermore, offspring of overweight mothers also present a worse metabolic cardiovascular risk profile(Reference Godfrey, Reynolds and Prescott3,Reference Gaillard5) .

Paternal pre-gestational BMI has been used as a negative control, and similar associations of parental pre-pregnancy BMI with offspring body composition and metabolic profile have been reported(Reference Santos Ferreira, Williams and Kangas6–Reference Rath, Marsh and Newnham8). Suggesting that these associations could be due to familial and environmental characteristics, such as diet, physical activity and genetic factors, or unmeasured confounders. Moreover, Bond et al (Reference Bond, Karhunen and Wielscher9) observed that offspring genotype explains 43 % of the covariance between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring BMI.

With respect to control for confounding, most of the studies have adjusted the estimates to post-conception variables, such as gestational weight gain, birth weight and offspring behavioural variables (eating habits and physical activity). These variables should not be considered as confounders, but mediators. By controlling for a possible mediator, a causal pathway is blocked and the magnitude of the association of maternal nutritional status with offspring body composition is underestimated. Indeed, studies that adjusted for possible mediators reported weaker association than the ones that did not control. Furthermore, in the presence of common causes between the mediator and offspring body composition that were not included in the analysis, such adjustment introduces collider bias, which magnitude and direction cannot be estimated(Reference Shrier and Platt10). Therefore, only variables that are possible confounders of the associations should be adjusted for. To evaluate the possible pathways in the association of maternal anthropometry with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition, direct and indirect effects should be estimated using appropriate statistical methods that adjust for confounders of the mediator – outcome association and take into consideration a possible interaction between exposure and the mediator(Reference Discacciati, Bellavia and Lee11).

Therefore, studies that assess the mediators or effect modifiers of this association are needed. Diet and physical activity would be possible mediators, because they are associated with anthropometric measures and body composition, as well as these health behaviours are generally shared with the family(Reference Poston, Harthoorn and Van Der Beek12). Another variable to be considered as a possible mediator is birth weight, as it is determined by maternal weight during pregnancy and is a predictor of the individual’s weight in other stages of life(Reference Schellong, Schulz and Harder13).

It is also important to evaluate if gender modifies the long-term consequence of maternal BMI in the pregnancy. Women, in general, have higher body fat averages, and some studies have observed that daughters of obese mothers have worse body composition(Reference Garawi, Devries and Thorogood14).

The current study was aimed at evaluating the association of maternal pre-pregnancy nutritional status with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition in adolescence and early adulthood. We also assessed if these associations were modified by gender, diet and physical activity and mediated by offspring birth weight, using data from three Brazilian Birth Cohorts.

Methods

Study design and participants

In 1982, 1993 and 2004, all maternity hospitals in Pelotas, a southern Brazilian city, were daily visited and all births identified. Those live births whose family lived in the urban area of Pelotas were examined, and their mothers interviewed (1982 n 5914, 1993 n 5249 and 2004 n 4231). These subjects have been followed up for several times at different ages. Further details on the cohorts methodology have been previously published(Reference Horta, Gigante and Gonçalves15–Reference Santos, Barros and Matijasevich17).

In the present study, we used data from the last follow-up of each cohort, which were carried out at 30, 22 and 11 years of age for the 1982, 1993 and 2004 cohorts, respectively. Subjects were invited to visit the research clinic, where they were interviewed and examined.

Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI

In the three cohorts, information on maternal pre-pregnancy weight was extracted from prenatal card or when absent by self-report, pre-gestational maternal weight was defined as weight before becoming pregnant. With respect to maternal height, in 1982 and 1993 the mothers were measured by the hospital staff and the data were retrieved from the hospital records, whereas in 2004 maternal height was measured at home in the 3-month visit. In all cohorts, height was evaluated using locally made portable stadiometers with a precision of 1 mm. As suggested by the WHO, those mothers whose BMI was < 18·5 kg/m2 were considered as underweight, normal weight by a BMI between 18·5 and 24·9 kg/m2, overweight was defined by a BMI ≥ 25·0 and ≤ 29·9 kg/m2 and a BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2 defined the presence of obesity. In the linear regression, body mass index was included as a categorical variable, in mediation analyses, we used maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on continuous form, because G-formula provide a total effect, natural direct and natural indirect effects and, no provide these estimates for each exposures category.

Offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition

Concerning the assessment of offspring body composition, weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg using a scale coupled to the BodPod (COSMED) with a maximum of 150 kg and height with a portable stadiometer (SECA 240; SECA), BMI was calculated dividing the weight by the squared height (kg/m2) and we used BMI z-score that was standardised for the sample, calculating BMI minus the mean, divided by the sd. Waist circumference was measured twice with an inextensible tape with an accuracy of 0·1 cm (CESCORF) and the average of these measures was used. Fat and lean mass were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar Prodigy; GE Healthcare®), and these measures were divided by squared height to estimate the fat and lean mass index in kg/m2.

Confounders and mediators

In the multivariable analysis, maternal schooling in years (0–4, 5–8, 9–11, ≥ 12), family income at birth in tercile, maternal age (< 20, 20–25, 26–30, > 30), parity (1, 2, ≥ 3) and maternal smoking during pregnancy (no/yes) were considered as possible confounders. These variables were evaluated in the perinatal studies. In the 1982 cohort, we also adjusted the analysis for a BMI allele score. The score was developed based on a genome-wide association study through the GIANT consortium, which identified 97 independent SNP associated with BMI at the genomic level of statistical significance (P < 5·0 × 10–8) in 322·154 individuals of European ancestry(Reference Locke, Kahali and Berndt18). Each SNP was multiplied by its per allele coefficient from a linear regression of BMI on the given SNP reported by GIANT; subsequently, a score was generated by the sum of these products for all 97 SNP for a given individual from the 1982 cohort.

Birth weight, a possible mediator, was collected in the perinatal study, live born was weighed soon after delivery by the hospital staff, using paediatric scales that were weekly calibrated by the research team, and information on birth weight was retrieved from maternity records. Physical activity and diet were considered as possible effect modifier. Physical activity and diet were collected at age 11 (2004 cohort), 22 (1993 cohort) and 30 (1982 cohort). Physical activity was measured using accelerometers, GENEActiv accelerometer (ActivInsights) for the 1982 cohort, and ActiGraph, wGT3X-BT, wGT3X and ActiSlee models for the 1993 and 2004 cohort. Subjects worn the accelerometers for seven consecutive days and, in the present study, we only considered the time spent in moderated and vigorous physical activity.

Offspring diet was assessed using a FFQ and was classified using different diet indexes, such as health eating index(Reference Previdelli, De Andrade and Pires19), total kilocalories of diet, kilocalories and grams of ultra-processed foods and block score(Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum20). The block score was the one that best explained the offspring diet. This score evaluates the intake of foods high in fibre and fat, assigning points for each frequency of consumption, and then a score for fibre and fat content of the diet was estimated(Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum20). Score varied according to the consumption of foods rich in fibre or fat and not according to the higher or lower content of these components in foods(Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum20); in the present study, we used block score as a continuous variable.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using Stata, version 14.0; descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations and percentages with 95 % CI were used to summarise continuous and categorical variables, respectively. ANOVA was used to compare the means of the outcomes according to maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, and multiple linear regression to adjust for possible confounders, and the analyses were stratified by gender, diet and physical activity. Mediation analysis was carried out using G-formula to decompose the total effect into natural direct and natural indirect effects of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition. se for mediation analyses were calculated using bootstrapping with 10 000 simulations. Separate models were fitted for each offspring outcome (BMI z-score, waist circumference, fat mass index and lean mass index) and mediator (birth weight). All models were adjusted for base confounders (family income at birth, maternal schooling, maternal age, parity and maternal smoking during pregnancy) and post-confounders (offspring schooling and family income at last visit).

In order to assess the impact of maternal diabetes or hypertension on the magnitude of the association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI with offspring anthropometry, we carried out sensitivity analyses, excluding those subjects whose mother had diabetes or hypertension in the gestation (1982 n 203, 1993 n 614 and 2004 n 900).

Results

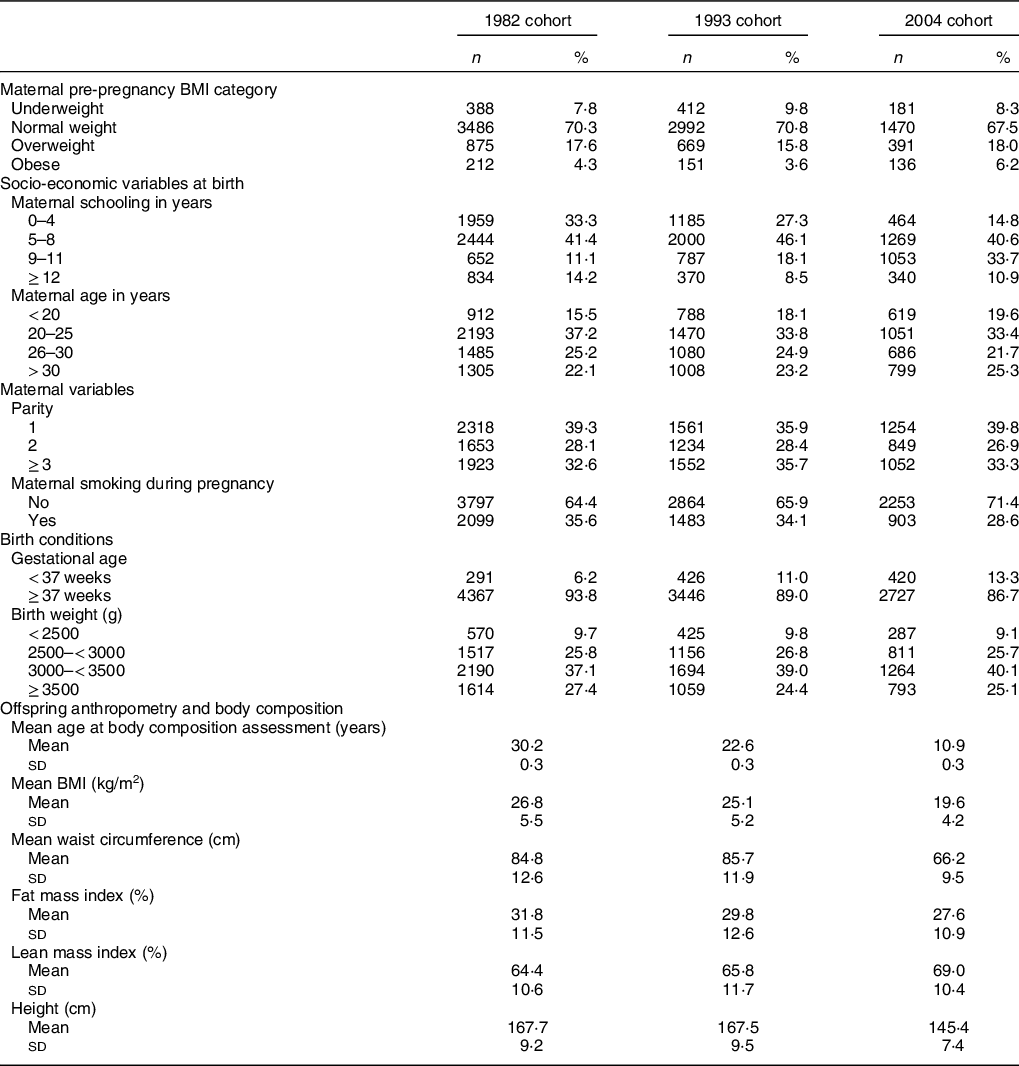

The present study included 3551, 3562 and 3467 participants of the 1982, 1993 and 2004 cohorts, respectively. Table 1 shows the distribution of the studied individuals according to baseline characteristics and offspring body composition. The proportion of mothers with 4 or less years of schooling decreased from 33·3 % in 1982 to 14·8 % in 2004. The prevalence of maternal smoking during pregnancy decreased from 35·6 % in 1982 to 28·6 % in 2004, whereas the proportion of preterm birth increased from 6·2 % to 13·3 % in the same period. The prevalence of maternal pre-pregnancy obesity increased from 4·3 % in 1982 to 6·2 % in 2004.

Table 1 Characteristics of the studied population of three Pelotas birth cohort studies

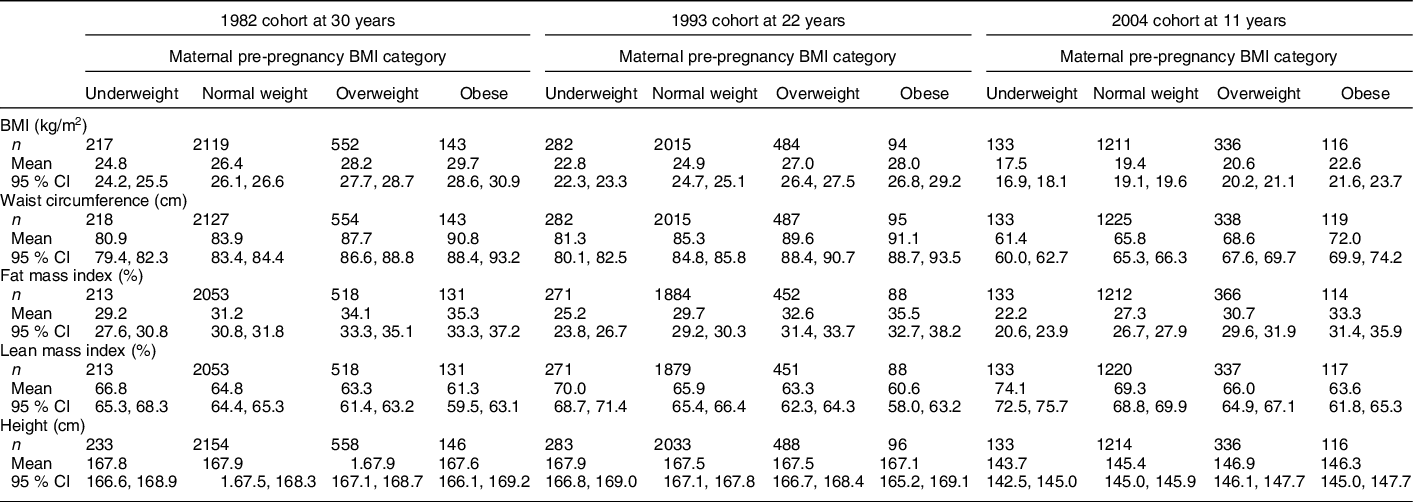

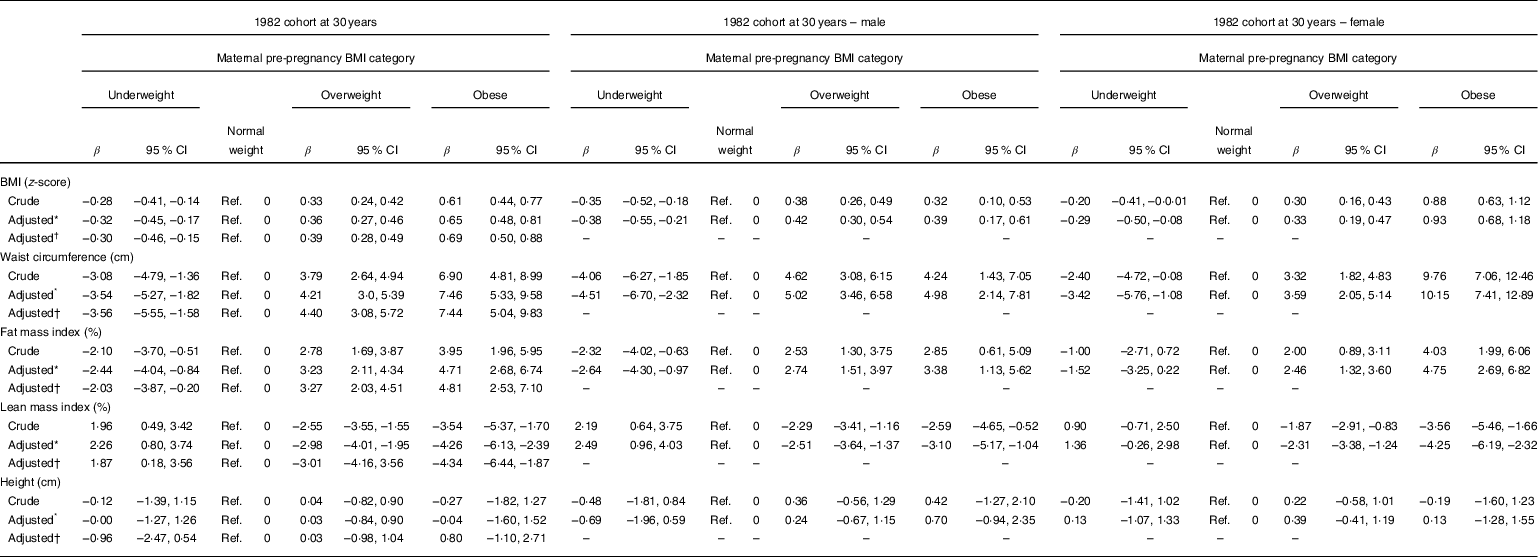

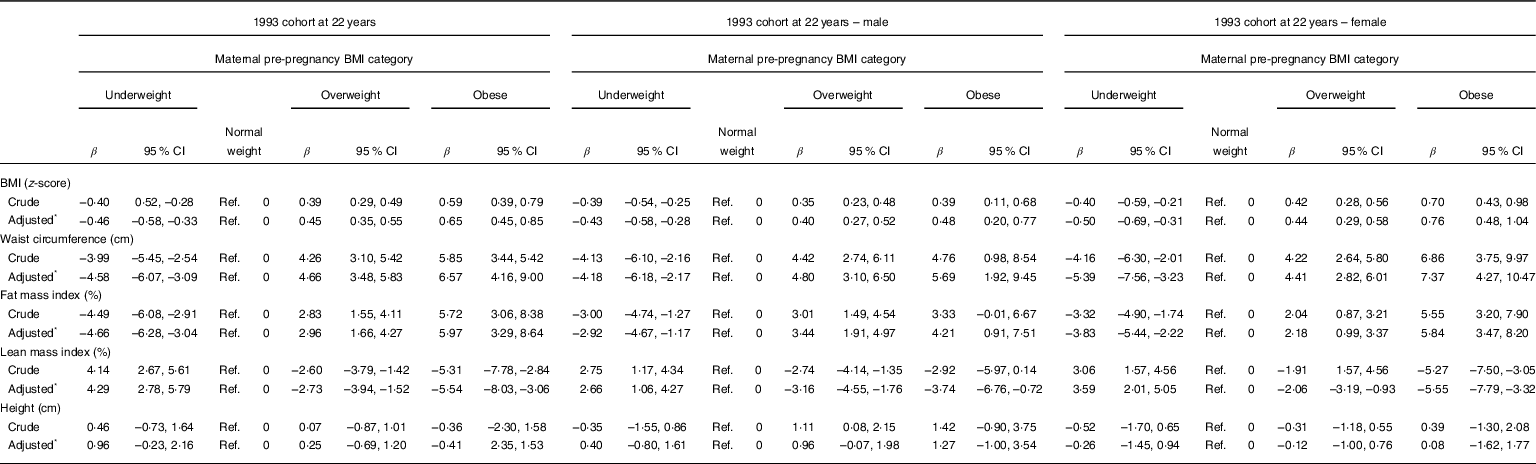

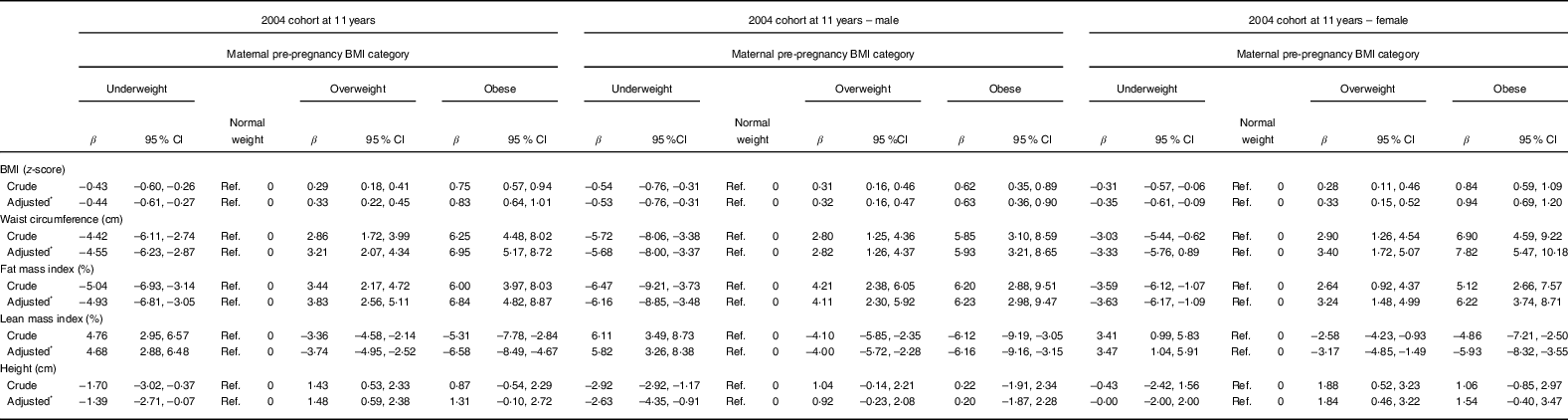

Table 2 shows that offspring mean BMI, waist circumference and fat mass index increased according to maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category. Tables 3, 4 and 5 show that adjustment for confounding slightly changed the magnitude of the associations, and the associations were similar across the cohorts, irrespective of the age at anthropometric assessment. In relation to offspring of normal weight mothers, BMI z-score was higher among those subjects whose mother was obese before pregnancy, with a difference ranging from 0·65 to 0·83 z-score. For waist circumference, the difference ranged from 6·57 to 7·46 cm, and for fat mass index from 4·72 to 6·84. In the analysis stratified by gender, the magnitude of the associations was higher among female offspring, but even among males the associations were statistically significant. Table 3 shows that adjustment for allele score of BMI had no material effect on the magnitude of the associations.

Table 2 Anthropometric measurements and body composition according to maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, in three Pelotas birth cohort studies

Table 3 Crude and adjusted analyses of association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring body composition and anthropometric measurements by gender, in 1982 Pelotas birth cohort study

* Adjusted: family income at birth, maternal schooling, maternal age, parity and maternal smoking during pregnancy.

† Adjusted for confounders and allelic score of BMI.

Table 4 Crude and adjusted analyses of association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring body composition and anthropometric measurements by gender, in 1993 Pelotas birth cohort study

* Adjusted: family income at birth, maternal schooling, maternal age, parity and maternal smoking during pregnancy.

Table 5 Crude and adjusted analyses of association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring body composition and anthropometric measurements by gender, in 2004 Pelotas birth cohort study

* Adjusted: family income at birth, maternal schooling, maternal age, parity and maternal smoking during pregnancy.

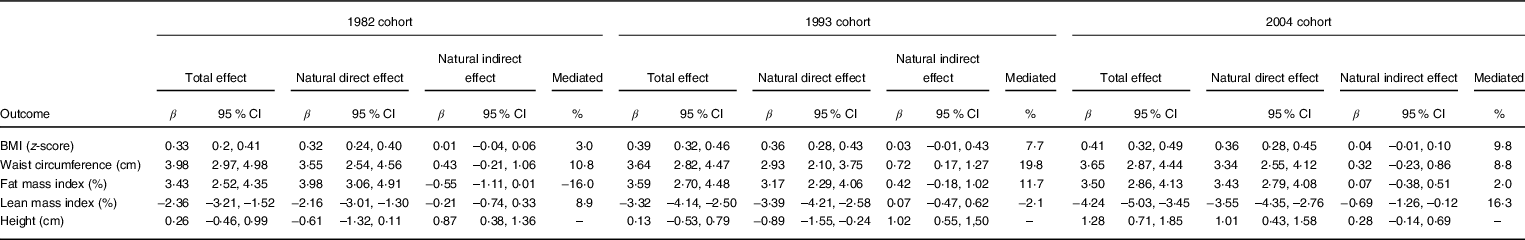

Concerning the mediation analysis, Table 6 shows that birth weight captured part of the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on offspring waist circumference in the 1993 cohort (0·72 (95 % CI 0·17, 1·27) and lean mass index in 2004 cohort (–0·69 (95 % CI –1·26, –0·12), approximately 20 % for waist circumference and 16 % for lean mass index. Concerning height, we observed that birth weight captured the entire effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI. Showing that birth weight has an influence on the height of children and that the maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is a possible positive confounding factor of this association, because the natural direct effect was negative for the 1982 cohort (–0·61 (95 % CI –1·32, 0·11) and 1993 cohort (–0·89 (95 % CI –1·55, –0·24).

Table 6 Mediation analysis* of association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring body composition and anthropometric measurements, in three Pelotas birth cohort studies

* Birth weight (g) as a mediator.

Birth weight did not explain part of the association with the other outcomes. However, it is possible to observe that for offspring BMI the pattern of measures of effect was similar between the cohorts, and birth weight decreased the potential to explain this association, according to the offspring age increases. In relation to fat mass index in the 1982 cohort, it was possible to observe that the natural direct effect (3·98 (95 % CI 3·06, 4·91) was greater than the total effect (3·43 (95 % CI 2·52, 4·35), indicating that birth weight would be acting as a negative confounding factor, underestimating the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on offspring fat mass index. However, this pattern of association was not evident in the other cohorts, which may indicate that this association was due to random variation, the same is observed for lean mass index in the 1993 cohort.

We also stratified the analysis by physical activity and diet. With regard to physical activity, it is possible to observe a reduction in the magnitude of association as the physical activity increases, suggesting that physical activity may attenuate the association of maternal pre-pregnancy obesity with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition; however, these associations were not statistically significant (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). On the other hand, for diet, we did not observe any clear pattern (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2).

The interaction analysis with the continuous variables (physical activity, diet and maternal pre-pregnancy BMI) showed that diet and physical activity moderated the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring BMI in the 1993 and 2004 birth cohort. For offspring waist circumference, diet moderated this association only in the 1993 cohort. For fat mass index, lean mass index and height only physical activity moderated the associations in the 1993 cohort (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3).

We carried out a sensitivity analysis comparing the results for the overall sample and that excluding those subjects whose mothers presented diabetes or hypertension during pregnancy. The magnitudes of associations were similar. However, we chose to keep the analyses only with mothers without previous morbidities, to maintain consistency with other studies that excluded those offspring whose mothers had previous morbidities (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

Discussion

In the present study, maternal pre-gestational BMI category was positively associated with offspring BMI, waist circumference, fat mass index and negatively with lean mass index. In spite of the difference in the age at assessment of the outcomes, the magnitude of the associations was similar among the cohorts, suggesting that pre-gestational maternal weight has a negative influence on offspring body composition that last until adulthood. Our results suggest that birth weight explains only a small portion of this association.

Most of the studies on this subject have reported similar associations(Reference Stamnes Køpp, Dahl-Jørgensen and Stigum7,Reference Rath, Marsh and Newnham8,Reference Stuebe, Forman and Michels21–Reference Chaparro, Koupil and Byberg33) . But, as previously mentioned, some of these studies included possible mediators in the multivariable analysis, which blocked a causal pathway and underestimated the magnitude of the associations. Because we did not adjust for mediators in the regression models, the present study was able to estimate the total effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category on offspring anthropometry and body composition.

The magnitude of the associations was modified by gender, a strong association was observed among daughters of obese mothers. It has been reported that women, in general, have higher levels of obesity compared with men. In addition to hormonal differences, this association is also possibly due to social causes such as gender inequality(Reference Garawi, Devries and Thorogood14).

With regard to possible mechanisms for the association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition, it has been suggested that this association could be due to intrauterine programming, offspring DNA methylation, shared genetic or confounding by familial lifestyle(Reference Godfrey, Reynolds and Prescott3,Reference Santos Ferreira, Williams and Kangas6,Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richmond34) .

In the present study, mediation analysis showed that birth weight captured a small part of the association. Based on studies that observed similar associations for maternal and paternal BMI category, we expected that offspring lifestyle such as physical activity and diet would capture part of the associations(Reference Santos Ferreira, Williams and Kangas6–Reference Rath, Marsh and Newnham8). Despite using different methods to measure diet, these variables failed to capture the association of maternal anthropometry with offspring body composition. Regarding the interaction analysis, it was only possible to observe moderation using the continuous variables. Diet was able to moderate the association only for offspring BMI. On the other hand, physical activity moderated the associations for offspring BMI, fat mass index, lean mass index and height. However, the results were not consistent among the cohorts.

These results may have been affected by measurement error, which tends to attenuate the indirect effect measures or interaction. Diet and physical activity are complex phenomena that are difficult to measure because they have several cultural and behavioural factors involved that we cannot satisfactorily establish. Leading to a higher probability of measurement error, which leads to an attenuation of the direct effect and for this reason we believe that it was not possible to observe part of the association captured by these variables, or that these variables moderated these associations.

Adane et al. evaluated the relationship between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring anthropometric measurements in childhood, and birth weight did not capture the part of this association(Reference Adane, Tooth and Mishra35). Such heterogeneity in the results may be due to accuracy of the information on birth weight. The current study gathered the data on birth weight retrospectively, with a long recall period, which may have introduced a misclassification error and underestimated the associations(Reference Adane, Tooth and Mishra35).

Concerning shared genetic factors, adjustment for a BMI allele score had no impact on the magnitude of the associations. The allele score, based on the findings of a large genome-wide association study, was strongly associated with offspring BMI in our cohort, thus suggesting that it captures at least some of the genetic component, but not all, given that BMI is a complex trait likely influenced by many genetic and environmental factors. Therefore, in the presence of genetic confounding, adjusting for the allele score would be expected to only attenuate, but not eliminate, the association. Because adjusting for the score did not attenuate (not even slightly) the association, shared genetic factors should not be considered as the main explanation for the long-term effect of maternal anthropometry in the pregnancy.

Concerning the study strengths, the association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition was evaluated using information from three Birth Cohorts, carried out in a southern Brazilian city. The results were largely consistent among the cohorts, which provides strong support against the possibility that our findings were due to chance. Moreover, confounders were assessed with a short recall time, minimising measurement error and reducing the probability of residual confounding. With respect to the outcomes, body composition was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, which is a method with high accuracy, decreasing the probability of measurement error and, therefore, of information bias(Reference Toombs, Ducher and Shepherd36). However, it should be noted that the body composition measures generated by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for people with obesity have greater variability, thus generating a lower accuracy compared to individuals with lower BMI values. But we believe that this fact does not bias the measures of association of the study since the measures generated by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry are in agreement with the other anthropometric measures of the study(Reference Laskey37).

As a limitation, we can point out that information on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category was based on self-reported data for height and pre-pregnancy maternal weight. However, a validation study carried out with data from Brazilian National Health Survey found a high agreement between self-reported and measured weight, height and BMI values(Reference Moreira, Luz and Moreira38). Furthermore, information on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category was collected just after delivery, reducing the likelihood of recall bias. Therefore, there is little risk of differential measurement error. Because this error was independent of offspring anthropometry and body composition, such error introduced a non-differential misclassification that attenuates (rather than exaggerating) the associations. Therefore, the observed associations are not due to measurement error of maternal BMI.

In conclusion, our results suggest that maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category is strongly associated with offspring anthropometric measurements and body composition at 11, 22 and 30 years old. Offspring whose mothers were overweight or obese had a higher BMI, waist circumference and fat mass index than those of normal weight mothers, and the magnitude of the associations was greater among the daughters, thus reinforcing the need for greater nutritional attention to the offspring of overweight and obese mothers. Prevalence of maternal overweight during pregnancy has sharply increased(Reference Horta, Barros and Lima39) and reinforces the importance of implementing interventions aimed at reducing the BMI.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The current study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. This article is based on data from the three Pelotas Birth Cohorts studies (1982, 1993 and 2004) conducted by Postgraduate Program in Epidemiology at Federal University of Pelotas with the collaboration of the Brazilian Public Health Association (ABRASCO). Financial support: The current study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. This article is based on data from the three Pelotas Birth Cohorts studies (1982, 1993 and 2004) conducted by Postgraduate Program in Epidemiology at Federal University of Pelotas with the collaboration of the Brazilian Public Health Association (ABRASCO). From 2004 to 2013, the Wellcome Trust supported the 1982 and 1993 birth cohort studies and for the 2004 birth cohort study from 2009 to 2013. The International Development Research Center, World Health Organization, Overseas Development Administration, European Union, National Support Program for Centers of Excellence (PRONEX), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq) and the Brazilian Ministry of Health supported previous phases of these studies. The European Union, National Support Program for Centers of Excellence (PRONEX), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq) and the Brazilian Ministry of Health and Children’s Pastorate supported previous phases of the study. A.M., A.J.D.B., A.M.B.M., F.C.L.F.B., F.C.W., H.G., I.S.S., M.C.F.A. and B.L.H. are supported by the CNPq. M.S.D. received a scholarship for a PhD’s degree from the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES). Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Authorship: M.S.D. and B.L.H. participated in all stages from conception, written part, data analysis and discussion of results. A.M., A.J.D.B., A.M.B.M., B.C.S., F.P.H., F.C.L.F.B., F.C.W., H.G., I.S.S. and M.C.F.A. revised the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was carried out according to the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by Research Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine, Federal University of Pelotas.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004887