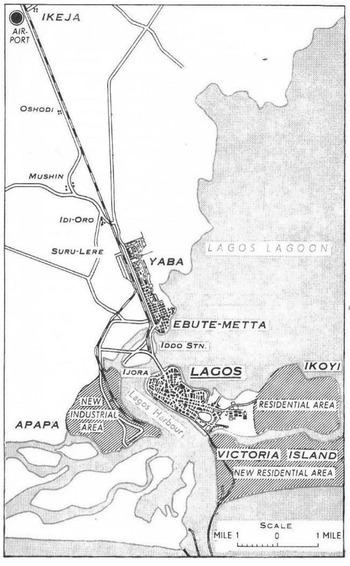

This article focuses on Ikoyi, a district of Lagos, to consider changing relationships between the colonial state, urban space, and race in Nigeria from 1935 to 1955. Ikoyi was a ‘European reservation’, a special zone constructed by colonial authorities to house white officials and representatives of Western companies (see Figure 1, below).Footnote 1 Urban spaces like the Ikoyi reservation formed an arena in which relationships between the state and race were contested. These debates helped to forge a late colonial state, a terminal form of colonial state that contained the seeds of its own destruction.

Fig. 1. Map of Lagos in the 1950s showing the Ikoyi reservation, marked as ‘Residential Area’. The reservation was surrounded by water to the north, south, and east, and was separated from the city of Lagos to the west by a ‘building free zone’.

Source: Federal Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Handbook of Commerce and Industry in Nigeria (Lagos, 1960), 26.

Some scholars have seen African cities as places where colonial states’ racialised power was exerted with particular intensity, for example through projects of segregation.Footnote 2 But the dense interrelationships between constructions of statehood, urban space, and race meant that cities were also strategic locations where colonial states’ racialised policies could be challenged.Footnote 3 At Ikoyi, diverse people contested racial segregation, including educated elite Nigerians, immigrants from the Eastern Mediterranean and India, British colonial officials, and Nigerian domestic servants. These groupings are problematic because they were partly produced by colonial-era classificatory projects. They remain analytically significant, however, because these efforts to classify affected individuals’ experiences of the state, space, and race, as well as the strategies employed to contest them.

Endeavours to reshape relationships between state, space, and race took a variety of forms, including street protests against segregationist policies, campaigning in the colonial Legislative Council and Nigerian-owned press, everyday practices at Ikoyi that defied racialised regulations, and bureaucratic disputes amongst colonial officials. Urban space thus formed an arena for negotiations which at once delineated the limits of state power, and contributed to making a late colonial state distinguished by distinct relationships with space and race.

A central feature of the late colonial state that emerged in Nigeria from the 1930s to the 1950s was that state authorities were forced to abandon explicitly racialised discourses of statehood and urban space. British officials presented the late colonial state as a postracial institution that was paving the way towards self-government, having recognised that overtly racialised standards no longer legitimised colonial rule. The late colonial years seemed like an epochal shift, as Nigerians won access to state posts and spaces from which they had been excluded. However, continuing implicitly racialised state standards and practices meant that, even as late colonial state authorities abandoned overt racial discrimination, Nigerians continued to experience the state and space in racialised ways.Footnote 4 White British officials retained a leading role in setting standards rooted in their own tacitly racialised norms, and the institutions and spaces bequeathed by the late colonial state to postcolonial Nigeria retained implicit associations with whiteness. The Nigerians and immigrants to Nigeria who successfully overcame overt racial exclusion struggled to challenge these implicitly racialised state standards in the same way.

These arguments address two key limitations of the existing literature on state, urban space, and race in West Africa. First, the literature on segregation has little to say about late colonialism. Much of the work on urban space and race during the colonial period has focused on the years from around 1900 to 1930, which have often been characterised as seeing especially intense racial segregation.Footnote 5 We know less about how relationships between states, urban space, and race changed in West Africa during the late colonial years from the 1930s to the 1950s, despite this being a crucial, transformative period. Segregation after 1930 has often been considered briefly and unpersuasively. Several scholars have advanced inadequate arguments proposing that visions and practices of segregation by race were largely replaced by projects of segregation by class.Footnote 6 These interpretations have overlooked the ways in which late colonial spaces often remained tacitly racialised. The periodisation for the decline of explicit racial segregation in colonial Africa has also remained unclear, with some scholars arguing for a turning point just after the First World War, some around 1930, and others around the time of the Second World War.Footnote 7 In Nigeria, however, explicit racial segregation declined from the later 1930s, and is best understood in relation to the wider emergence of a late colonial state as the country recovered from the Depression.

Second, the literature considering late colonialism as a distinct period in African history has had little to say about urban space and race, despite their importance to late colonial statehood. Exploring the spatial and racial aspects of late colonialism contributes to the conceptualisation of this important and increasingly widely used term. There have been surprisingly few attempts to define late colonialism. It has most frequently been deployed in scholarship on Africa as a loose form of periodisation, which has left unclear exactly what distinguished the late colonial years.Footnote 8 The rare work that has sought to conceptualise late colonialism has seen it as characterised by particular manifestations of statehood, including the rapid expansion of state institutions and more intrusive developmentalist policies, but has offered few glimpses of its important spatial and racial dimensions.Footnote 9

Earlier research that emphasised the importance of bargaining, ‘collaboration’, and negotiation in colonial rule is helpful in exploring how a late colonial state was forged, in part, by challenges to racial segregation at particular urban locations.Footnote 10 Late colonialism in Nigeria was not a generalised, ethereal condition. It was shaped by specific interactions between specific people in specific spaces, that forced a shift from explicitly to implicitly racialised state standards. Bridging the literatures on space and race, on the one hand, and late colonial statehood, on the other, promises to bring them into a mutually enriching dialogue.

A range of sources illuminate the emergence of late colonialism at Ikoyi. Colonial archives hold evidence of debates amongst British officials, as well as petitions from educated Nigerians and letters from Eastern Mediterranean and Indian immigrants, that afford insights into how they sought to remake relationships between state, space, and race. Nigerian servants, their families, and friends left little evidence of their own experiences of life at Ikoyi, but reading colonial archives against the grain offers valuable, underexplored perspectives on how they sought to contest regulations at the reservation. Ikoyi was debated in the Nigerian press and the colonial Legislative Council, and represented in novels, sources that elucidate the racialised — and gendered — construction of state and space at Ikoyi. Unfortunately, they have less to say about the politics of ethnicity, and, in consequence, so does the article.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, this evidence shows how debates about the spaces of Ikoyi reshaped broader understandings of statehood and race.

Lagos and Ikoyi

Ikoyi is an apt location to study the changing relationships between state, space, and race. British colonial authorities constructed the Ikoyi reservation from 1919 to house white officials and businessmen, excluding all Nigerians from residence except domestic servants. They intended reservations as racialised spaces that would facilitate circulations of white Westerners around the empire, protect them from tropical diseases, and uphold colonial-era racial hierarchies. The British only established reservations in colonies: senior civil servants in Britain itself did not live in special enclaves of state-owned housing.

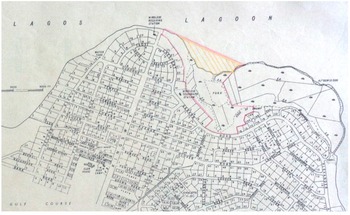

Ikoyi was planned with large, widely spaced bungalows intended for white Europeans, much smaller quarters for Nigerian domestic servants, and extensive gardens. Like many other reservations in British-controlled West Africa, Ikoyi was located on the outskirts of an existing town, and was separated from it by a ‘building free zone’ of 440 yards, which the British understood to be the flying range of malaria-carrying anopheline mosquitoes (see Figure 2, below).Footnote 12 Reservations were supplied with better access to utilities, including piped water, than neighbouring districts largely inhabited by Africans. Ikoyi included leisure facilities intended for white householders only, including a social club and golf course. Limited Nigerian state revenues were disproportionately focused on this small enclave, which allowed many British colonial officials to live in a grander style than if they had remained in Britain.Footnote 13

Fig. 2. Detail of a 1955 plan of Ikoyi. Note the low-density plots for bungalows in the north and east, and the denser concentrations of flats in the south west. The ‘building free zone’ separating the reservation from the city of Lagos was occupied by the golf course marked in the south west. The area on the banks of the lagoon hatched in pencil was the site for a proposed land reclamation project.

Source: NAI Comcol1 3911, ‘Plan of Ikoyi’ (1955). Courtesy of National Archives, Ibadan.

Ikoyi was part of a much older city. The growth of Lagos from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries was rooted in trade, including the trade in enslaved people.Footnote 14 Lagos comprised overlapping ‘quarters’ that were consolidated after the 1851 enforcement of a British consulate and the subsequent 1861 annexation.Footnote 15 Isale Eko, the oldest part of the city at the northwest of Lagos Island, was home to the oba's palace and major markets. By the 1840s, Afro-Brazilians, formerly enslaved Africans who returned from Latin America, came to Lagos in growing numbers, with many settling at the ‘Portuguese Town’ to the east.Footnote 16 The Saro, formerly enslaved Africans from Sierra Leone, increasingly moved to Lagos from the 1850s, and especially to Olowogbowo in the southwest of the island.Footnote 17 After the annexation, European merchants and British colonial officials dispossessed Africans to lay out the marina along the south of Lagos Island from the 1860s.Footnote 18 Yet the relatively small size of the island, and the informal nature of the quarters, meant that long-established Lagosians, Afro-Brazilians, Saros, white Westerners, and Yoruba migrants from the hinterland often lived in close proximity.Footnote 19

The British at first sought to govern Lagos through collaboration with Western-educated African elites, and some Africans held senior posts within the colonial administration. This changed from the final decades of the nineteenth century, as British officials increasingly sought to exclude Africans from senior state positions and emphasised segregationist policies.Footnote 20 The construction of Ikoyi was the product of hardening ideologies of racial difference, which the British combined with new forms of knowledge about medicine and town planning.Footnote 21 From around the turn of the century, British authorities established reservations for white officials at centres of colonial administration across West Africa, drawing on the model of earlier reservations that the British had built in India.Footnote 22 In 1901, a reservation was established at Accra, the capital of Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast), and the ‘Hill Station’ at Freetown, Sierra Leone, was built from 1902. In Nigeria, reservations were established at Ibadan and Kaduna from around 1900.Footnote 23 From 1907, Lagosian educated elites challenged, with some success, a government plan to turn the area around the racecourse into an exclusive zone for Europeans.Footnote 24 But in 1919 the colonial governor, Sir Frederick Lugard, complained that at Lagos ‘the residences of Europeans and natives are … hopelessly intermixed’, and the construction of the Ikoyi reservation commenced that year.Footnote 25

The Ikoyi plains to the east of Lagos Island were selected as the site because they were close to the city's administrative and commercial centre, and were seen as sparsely populated. Lagos elites contested the plans, though, and the colonial government's 1919 acquisition of the land proved controversial. The government rejected a claim by Chief Onikoyi to own the land. The government maintained that it had already acquired the area through the 1908 Ikoyi Lands Ordinance, which had required landowners to register ownership within a year or forfeit their land. The Onikoyi family unsuccessfully challenged this ruling in the courts during the 1920s, and eventually settled for token compensation. As the historian Patrick Cole observed, the case was ‘a classic example of the government … taking advantage of the ignorance and illiteracy of the Idejo [land-owning] chiefs to appropriate large areas of land’.Footnote 26 The building of the reservation was also vigorously opposed by chiefs, newspaper editors, and other prominent Nigerians who signed a 1922 petition arguing that the government's construction of the Ikoyi reservation caused overcrowding elsewhere in Lagos, and contributed to an outbreak of the plague.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, the first colonial officials moved into the new reservation in 1923.Footnote 28

The colonial state's claims to ownership of the land and housing, together with the reservation's particular forms of planning and infrastructure, made Ikoyi a distinct area of Lagos. At reservations, colonial authorities sought to classify people by race, assign them to specific hierarchical social and spatial locations, and regulate their activities. Ikoyi was also intended as gendered space. The vast majority of colonial officials were male. Few brought their families to Nigeria in the 1920s and 1930s, and regulations stipulated that all resident domestic servants at Ikoyi should be male.Footnote 29 At the same time, Ikoyi was never entirely separate from the rest of the city. Most colonial officials and Western businessmen who lived there worked in offices around the racecourse and marina, and the Nigerian domestic staff often visited, and were visited by, friends and family resident in other parts of Lagos. Into the 1950s, the reservation only occupied part of Ikoyi, and was traversed by Nigerians travelling between villages in eastern Ikoyi and the rest of Lagos, to the chagrin of some British officials.Footnote 30 In practice, colonial authorities often struggled to enforce policies of segregation at Ikoyi.

Reservations form useful barometers for the emergence of late colonial states from the 1930s to the 1950s. People experienced late colonialism in part through encounters with a changing geometry of state, space, and race. More diverse people lived at reservations as late colonial states disavowed explicit racial discrimination. By the 1950s, bungalows at Ikoyi were occupied by Nigerians holding senior civil service jobs, and by Eastern Mediterranean and Indian immigrants to Nigeria, as well as by white Europeans. Nevertheless, as we will see, experiences of Ikoyi remained tacitly racialised. These patterns were mirrored elsewhere in late colonial West Africa, for example at reservations in Ghana.Footnote 31

Late colonialism also involved the growth of the Ikoyi reservation. As late colonial states employed more officials to implement developmentalist projects, housing shortages at reservations and the construction of new housing followed. In Nigeria, this was underway from the later 1930s as the colonial state's revenues started to recover from the Depression.Footnote 32 Blocks of flats were built at Ikoyi for the first time to accommodate an influx of British staff.Footnote 33 During the war years, when Nigeria was a significant Allied logistics hub, and after 1945, as colonial development programmes accelerated, yet more British officials were stationed to Nigeria.Footnote 34 Building work and severe housing shortages were not unique to late colonial Ikoyi. Reservations were extended elsewhere in Nigeria, including at Ibadan and Kaduna.Footnote 35 New reservations, such as Ikeja in Lagos (established in 1946), were constructed.Footnote 36 Similar trends emerged elsewhere in British-controlled West Africa. At Freetown in Sierra Leone, the expansion of the Hill Station and planning of new residential areas for Europeans were underway from the later 1930s, as at Ikoyi.Footnote 37 In Ghana, postwar housing shortages affected reservations at Accra, Kumasi, and Koforidua.Footnote 38 Reservations were extended, and a new reservation established in Accra near the airport.Footnote 39 At Ikoyi and beyond, reservations were key sites in the emergence of late colonial states.

Educated Nigerians

When the first white officials moved into Ikoyi in 1923, Nigerians who had encountered ‘Western’ forms of education were barred from living there. The colonial government's ‘indirect rule’ alliance with Nigerian chiefs marginalised the educated elite, and offered them limited access to state posts and spaces.Footnote 40 During the late colonial years, educated Nigerians successfully protested against their racialised exclusion from reservations. Elites along the West African coast had called for improved access to colonial states’ resources since the nineteenth century.Footnote 41 They were afforded new opportunities during the 1930s by British officials’ inadequate response to the Depression, the ensuing protests across West Africa and the West Indies, and increasing international scrutiny of British colonial administration.Footnote 42 With British authorities on the back foot, educated Nigerians contested their exclusion from reservations using assets including their representation on the colonial Legislative Council and newspaper ownership. Educated Nigerians’ campaigning for equal access to housing designed for white colonial officials discredited overtly racialised discourses of statehood and space, helping to forge a late colonial state, but focused less on implicitly racialised understandings. They won access, but at the cost of implying that reservations were a suitable institution for late colonial and postcolonial Nigeria.

During the 1930s, educated Nigerians’ challenge to reservations adopted two strategies. One, more short-lived, approach was to critique reservations’ expense. Nigerian Legislative Council members pointedly enquired about reservations’ cost. In 1937, for example, Dr C. C. Adeniyi-Jones, the Second Member for Lagos, asked about renovations to Ikoyi bungalows, noting that ‘the taxpayers … have to foot the bill at all times’.Footnote 43 This line of attack questioned the relevance of these expensive state spaces to a relatively poor country like Nigeria.

Educated Nigerians’ second strategy proved more enduring. This approach focused not on reservations’ expense, but on educated Nigerians’ racialised exclusion from these spaces. Senior civil service positions, known in the 1920s and early 1930s as ‘European posts’, entitled white British officials to housing at reservations. Of the hundreds of these jobs, Nigerians occupied only 15 in 1934, and they were barred from reservation housing.Footnote 44 Nigerian Legislative Council members and the Nigerian-owned press repeatedly raised the issue of access to these posts, and to reservations. In 1937 and 1938, for example, Adeniyi-Jones tabled Legislative Council questions about Nigerian civil servants’ access to government housing; and the West African Pilot complained in 1937 that the appointment of Nigerians to senior posts was proceeding ‘at a snail's pace’, noting that the conditions of service, which included housing, were ‘more favourable to the non-Africans’.Footnote 45

Claiming equal access to reservation housing proved a successful tactic. From the later 1930s, colonial authorities started to abandon explicitly racialised discourses around reservations. At least one black African civil servant actually lived at a reservation from 1937. That year, one British official noted that an African medical officer at Makurdi ‘lives in the European reservation with the full approval of the Europeans therein’.Footnote 46 In 1938, British officials replaced the official name ‘European reservation’ with the racially neutral term ‘government residential area’ (or ‘GRA’).Footnote 47 This shift recognised that at least one black African already lived in a reservation, and opened the way for more. Explicitly racialised discourses around reservations in Nigeria started to be abandoned from the later 1930s, and educated Africans lived in reservations earlier than the dates proposed in the literature, which include 1944, 1947, and 1952.Footnote 48

Awkward questions about the record of British colonial rule during the Depression made British administrators increasingly reluctant to defend explicitly racialised exclusion. Sir Bernard Bourdillon, the colonial governor of Nigeria, in 1936 announced a new policy of ‘affording Africans wider opportunities for appointment’, and the following year Dr Ladipo Oluwole ‘made local medical history’ when promoted to Medical Officer of Health.Footnote 49 Change was slow but steady: 54 Nigerians held senior posts by 1940, an increase of 39 over six years.Footnote 50 By the war years, Nigerian officials’ residence at reservations was still unusual, but the principle had been established. As one British official wrote in 1944, ‘Africans holding superior appointments living in Govt. quarters in a G.R.A. suitable to their status … has been decided in the affirmative and works quite all right’.Footnote 51 As the British sought to mobilise Nigerian support for the war against Nazism, many colonial officials were unwilling to uphold overt racial discrimination.Footnote 52

During and after the war, educated Nigerians continued to attack their racialised exclusion from state housing. A 1943 Nigerian Civil Service Union petition, signed by over 2,000 members, demanded ‘equal rights and privileges to African officers appointed to executive posts’, including ‘accommodation in Government quarters befitting their official position, free of charge’.Footnote 53 Unlike their white British colleagues, the few Nigerian civil servants who lived at reservations had to pay rent. The hearings of the 1945–6 Commission on the Civil Services of British West Africa, overseen by the British judge Sir Walter Harragin, offered a new arena for educated Nigerians to renegotiate relationships between state, space, and race. The Supreme Council of Nigerian Workers, representing trade union members, demanded in 1946 that Africans in senior posts ‘must maintain the same standard of living as the European with whom he is to rub shoulders’, and noted that ‘the African is not provided with free quarters’.Footnote 54 Now that the British had retreated from explicit racial exclusion at reservations, these were powerful arguments. Harragin agreed with them, and his 1947 report stated that African senior officials ‘should be supplied with a house on the same terms as his European confrere’.Footnote 55

Educated Nigerians’ responses to the notorious 1947 Bristol Hotel incident further discredited explicit racial exclusion. The incident saw the white European manager of the Bristol Hotel in Lagos deny residence to Ivor Cummings, a black British colonial official.Footnote 56 A subsequent mass meeting called for the government to ban ‘all discriminations in public institutions’ including ‘residences’, and especially at ‘places which owe their establishments and maintenance’ to ‘public funds’.Footnote 57 The Nigerian-owned press mobilised to condemn the incident. This, together with angry street protests, elicited a 1947 government circular prohibiting the ‘colour bar’ and a public statement from the governor, Sir Arthur Richards, declaring that racial segregation was now ‘an anachronism’.Footnote 58

Educated Nigerians’ concurrent campaigns for constitutional change also widened access to reservations. The new 1946 constitution expanded the Legislative Council to include more members from across Nigeria.Footnote 59 These Nigerian representatives in 1949 requested special housing for when the Council met in Lagos, specifying that it should be in Ikoyi, ‘which is preferred to Lagos Island or the Mainland’.Footnote 60 The construction of 24 flats was duly ordered, together with around 8,500 items to furnish them, including fish knives and jam spoons.Footnote 61 Legislative Council members temporarily took over two existing blocks of Ikoyi flats while the new flats were under construction. When a fire broke out during the evening of Sunday 20 November 1949, Mallam Muhammad, Wali of Bornu, left hurriedly and met outside ‘[t]he Sardauna of Sokoto and Mallam Abubakar Tafawa Balewa … looking after their loads which were being taken out by their boys’.Footnote 62 The presence of these distinguished northern Nigerian politicians at Ikoyi would have been inconceivable a few years before, and testified to Nigerians’ success in challenging overt racial exclusion from reservations. Nigerian politicians and civil servants were a common sight at Ikoyi by the mid-1950s. Chinua Achebe, for example, moved to Ikoyi in 1954 when he took up a post in the Nigerian Broadcasting Service.Footnote 63 Reservations showcased the increasing diversity of late colonial officialdom, exemplifying how educated Nigerians successfully challenged explicit racialised exclusion and in the process forged a distinctively late colonial state.

However, late colonial experiences of Ikoyi remained tacitly racialised. Nigerian householders could unsurprisingly feel uncomfortable in spaces designed by and for, and still largely inhabited by, white British officials. This was addressed in novels of the time written by authors who themselves lived at reservations, including Achebe and T. M. Aluko. These works often depict reservations’ new Nigerian residents as isolated and unsettled. For Achebe's protagonist Obi Okonkwo, a young civil servant in No Longer at Ease (1960), ‘Ikoyi was like a graveyard. It had no corporate life – at any rate for those Africans who lived there’.Footnote 64 White people continued to dominate the spaces of Ikoyi, and their interactions with Nigerians were often superficial. The continuing tacit racialisation of space was reflected in de facto segregation within reservations. Hugh and Mabel Smythe, American sociologists who worked in Nigeria from 1957 to 1958, observed that at reservations, ‘a great many apartment buildings tend to become all-Nigerian after one Nigerian family moves in’, suggesting that white British officials remained reluctant to live alongside their Nigerian colleagues.Footnote 65 Tacitly racialised exclusion continued to shape life at late colonial reservations.

Ironically, the success of educated Nigerians’ campaigns against overt racial exclusion contributed to reservations’ rapid and costly expansion during the 1950s. Federal and regional governments sought to provide reservation housing for all senior officials, Nigerian and British, employed in the rapidly expanding civil service. Even as the transfer of power neared, the federal government reclaimed swampland at Ikoyi to permit the construction of new bungalows.Footnote 66 This was an odd outcome. The British established reservations as overtly racialised colonial-era institutions. But educated Nigerians’ calls for equal access to reservations, rather than for their abolition, implied that reservations were an appropriate state institution for Nigeria, and contributed to their enlargement during the late colonial years. The inequalities inherent in providing senior state officials with expensive reservation housing would be inherited by postcolonial Nigeria.

Educated Nigerians’ campaigning about reservations was thus at once a triumph and a disaster. They helped to forge a late colonial state by discrediting explicit racial exclusion, but the dynamics of educated Nigerians’ campaigns contributed to the expansion of these tacitly racialised spaces. They tended not to focus on the continuing relationships between reservations and whiteness, or reservations’ suitability for an independent African nation. The historian E. A. Ayandele in 1973 argued that the ‘so-called nationalists … bellowed because they wanted that the educated elite be put into such cushy “for the whites only” positions and enjoy the same privileges’.Footnote 67 His comments captured the way late colonial campaigns against explicit racial exclusion could leave more subtly racialised institutions unexamined. Later scholars, including Philip S. Zachernuk, have also suggested that Nigerian educated elites failed to articulate a coherent critical response to colonial institutions during the late colonial years.Footnote 68 These criticisms reflected educated Nigerians’ ambivalent achievements in negotiating a late colonial state at Ikoyi, but at the same time have understated their dogged challenge to racial segregation, which overcame their overtly racialised exclusion from reservations earlier than many scholars have acknowledged.

Migrants to Nigeria

Historians have had little to say about the negotiation of state, space, and race at reservations by migrants to Nigeria aside from white Westerners.Footnote 69 Like educated Nigerians, migrants to Nigeria with roots in the Eastern Mediterranean or India challenged explicitly racialised exclusion. They won access to reservations, but proved less able to challenge implicitly racialised late colonial standards.

These migrants to Nigeria were diverse, but shared an uncomfortable position as a small minority in colonial society. British officials did not see them as Westerners, despite Eastern Mediterranean migrants often claiming whiteness, and many Nigerians treated them as outsiders.Footnote 70 Some wanted to live at Ikoyi, but migrants lacked educated Nigerians’ campaigning resources such as Legislative Council representation. They therefore did not publicly campaign for access, but applied individually to lease plots using a process that colonial officials intended for white businessmen.Footnote 71 Migrants’ efforts to challenge overt racial exclusion at Ikoyi helped to produce a late colonial shift, ostensibly from racial standards to standards rooted in social class. However, examining how British officials considered migrants’ applications for Ikoyi plots highlights the tacit role of race in their thinking about class.

British officials rejected migrants’ applications for Ikoyi plots outright until the later 1930s. In 1937, for example, they informed an Egyptian applicant that ‘sites at Ikoyi are reserved for persons of European descent’.Footnote 72 After colonial officials replaced the overtly racialised nomenclature ‘European reservation’ in 1938, they still viewed reservations in tacitly racialised terms. This is clear from their consideration of the next migrant to Nigeria who applied for an Ikoyi plot: Mr Jivatsing, the Lagos manager of the Indian-owned trading company K. Chellaram and Son. Chellarams owned a chain of stores in Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone that specialised in ‘fancy goods, provisions, haberdashery, [and] footwear for men, women and children’.Footnote 73 Jivatsing applied for a plot twice, in February and June 1944. He consciously probed the racialised nature of space at Ikoyi, asking for example that colonial officials ‘kindly make explicit to us why’ his applications were rejected.Footnote 74

The British officials who considered Jivatsing's applications generally agreed that ‘persons of any race are eligible to lease plots in Government Residential Areas’, and that ‘standard of living is the criterion’, which implied that social class was now the main standard for assessing reservations’ prospective residents.Footnote 75 British officials accordingly viewed Jivatsing relatively favourably. As ‘a man of some standing and means’, he could ‘be expected to conform to the health standards required in a Government Residential Area’.Footnote 76 But British authorities had doubts about Jivatsing's Indian employees, whom he also wanted to house at Ikoyi. After Jivatsing's second application, British officials took the remarkable step, given that there was no suggestion that he had committed any offence, of ordering a CID (Criminal Investigation Department) enquiry. It alleged that Jivatsing and his staff ‘live a communal life in quarters above the firms [sic] shop … in conditions said to be little above African standards’, showing how — amongst themselves — many British officials still understood social class and different ways of life in terms of a racialised hierarchy.Footnote 77 One argued that there was ‘some difference between making a plot available for Chellaram's manager who is known to be a man of some standing and culture … and making one available for the purpose of erecting barracks for the firm's underlings’.Footnote 78 British officials rejected the applications because they saw only Jivatsing himself, and not his employees, as likely to uphold Ikoyi's tacitly racialised standards, which were based on the behaviour white British colonial officials expected from each other. Because late colonial state authorities now publicly forswore racial exclusion, they kept this reasoning private, issuing bland explanations stressing the limited space at Ikoyi.Footnote 79 Jivatsing and his colleagues were barred from the reservation because, as a group, they were not deemed likely to conform with these tacitly racialised standards of behaviour.

When a migrant eventually applied for an Ikoyi plot successfully, it was because he ranked highly on colonial officials’ racialised hierarchy of standards, and benefitted from educated Nigerians’ campaigning. One day in August 1946, a man asked at a Lands Department office to lease an Ikoyi plot. Clover, the British official who dealt with the enquiry, ‘did not clearly hear this gentleman's name at the time and from his appearance took him to be a European’. Clover therefore ‘informed him that his name would be added to the waiting list’.Footnote 80 When Clover later received a letter from the man, he noticed that his name was Mattar. Clover asked the CID to investigate Mattar, who, again, was not suspected of wrongdoing. These enquires revealed that Mattar was ‘a British subject by birth, of Syrian parentage’, who had ‘served in the British Army and held the rank of Captain’.Footnote 81 Clover's verbal acceptance of Mattar's application, based on his mistaken assessment of Mattar's ethnicity, created a situation one British official described as ‘a little delicate’.Footnote 82 Some were concerned that granting Mattar a lease may create ‘an undesirable precedent’, but another official argued that Mattar was ‘as suitable a candidate for a plot in Ikoyi as any non-European is likely to be’, a comment which again implied a racialised hierarchy of class.Footnote 83 Mattar's service as a commissioned officer in the British army meant that most colonial officials were prepared to locate him as high on their hierarchy of standards as was possible for a person that they did not view as white. Colonial authorities granted him the lease in October 1947, partly because of the colonial governor's recent measures to abolish overt racial segregation in the wake of the Bristol Hotel protests.Footnote 84 Educated Nigerian campaigns against the colonial state's racialised standards helped to open the way for Mattar to live at Ikoyi.

These migrants to Nigeria mobilised fewer campaigning resources than educated Nigerians, but still helped to make a late colonial state by challenging explicitly racialised standards of statehood and space. Their experience shows the diversity of those involved in forging late colonialism. Even when explicitly racialised exclusion had been abandoned, however, British officials still sought to regulate Ikoyi according to standards rooted in their own, implicitly racialised, norms. Like educated Nigerians, migrants to Nigeria gained access to Ikoyi, but proved less able to challenge tacitly racialised late colonial understandings of statehood and space.

Colonial officials

Reservations featured prominently in debates amongst another group of migrants to Nigeria, white British colonial officials. They retained substantial control over the levers of the late colonial state from the 1930s to the 1950s, but found it increasingly difficult to agree amongst themselves about reservations. Many British officials questioned explicit racial exclusion, but even they proved less willing to interrogate their implicitly racialised thinking about statehood and space.

British officials formed a more heterogenous group as a larger, more developmentalist late colonial state emerged in Nigeria from the later 1930s. Administrative officials faced new challenges from their specialist colleagues, such as medical officers, who were recruited in larger numbers.Footnote 85 The meanings of late colonial statehood and space were increasingly negotiated amongst British officials. Generalist colonial administrators based in Nigeria, rather than — as Carl Nightingale has suggested — the Colonial Office in London, took the initiative in abandoning overt racial exclusion at reservations.Footnote 86 Specialist medical officials, supported by the Colonial Office, unsuccessfully argued for continued racial segregation. These debates suggest the limitations of seeing late colonial state-building as chiefly a ‘triumph of the expert’, in which specialist officials wielded increased influence.Footnote 87

Medical officers argued that explicit racial segregation was necessary to protect British officials’ health, and banned all Africans — apart from male domestic servants — from living in reservations. ‘Native children should on no account be allowed to reside within the reservation’, wrote a sanitary officer in 1919, reflecting colonial medical officials’ view that African children were especially infectious carriers of tropical diseases.Footnote 88 He also sought to bar ‘native women … without a special pass’.Footnote 89 These regulations sought to minimise Africans’ residence at reservations.

By the later 1930s, medical officials vociferously complained about the lax enforcement of these rules. Rupert Briercliffe, the director of Nigeria's medical department, in 1936 objected to ‘large numbers of African children (and … servants and their wives)’ living at Lagos reservations.Footnote 90 He demanded changes to exclude Nigerian children and limit resident servants to one per household. The problem for Briercliffe was medical officials’ restricted powers over reservations: they could usually only request that householders evict unauthorised Nigerian residents, including servants’ family members and friends.Footnote 91 P. S. Selwyn-Clarke, the medical department's deputy director, escalated the dispute in 1937. He complained that colonial administrators were not properly enforcing segregation, and appealed directly to the secretary of state for the colonies in London. Selwyn-Clarke called for ‘the exclusion of African children’ from reservations, the prohibition of African women at night, fewer resident male servants, and greater powers of enforcement.Footnote 92 A 1938 conference of medical officials from across British-controlled West Africa endorsed this agenda. They emphasised that ‘the number of Africans, who form the reservoir of infection, living in residential areas should be very strictly limited’.Footnote 93 Explicit racial segregation retained widespread support amongst colonial medical officers in the later 1930s, and enjoyed considerable support at the Colonial Office as well. William Ormsby-Gore, the secretary of state, wrote to Bourdillon in 1937 that ‘the good results achieved by the policy of segregation’ should not be ‘obscured by other, e.g. political, considerations’.Footnote 94 Overt segregation at reservations still had vocal advocates within the colonial establishment.

But this was not to be a triumph of expert medical officials. Colonial administrators in Nigeria, under pressure from educated Nigerians’ campaigning, and aware that explicit racial segregation was becoming a political liability, successfully sidelined medical officers’ proposals. Bourdillon dismissed Selwyn-Clarke's plans as ‘extreme’, and most senior administrators supported the governor.Footnote 95 Sir William Hunt, the chief commissioner of the southern provinces, argued that segregation was more a ‘political’ than a ‘hygiene’ matter, for example, and advocated segregation by ‘standard of living’ — that is, by social class — instead of overt racial exclusion.Footnote 96 Colonial administrators’ 1938 decision to change reservations’ official name to ‘government residential areas’ proved decisive in this tussle. Bourdillon informed the secretary of state that ‘normally residence in these areas should be confined to Europeans’, effectively permitting some Nigerian householders.Footnote 97 Officials at the Colonial Office quickly realised that this was a decisive intervention, with R. E. Turnbull of the West African Department shrewdly suggesting that ‘the policy of the Medical Department has been effectively killed’.Footnote 98 The administrators retreated from explicit racial segregation, giving way to educated Nigerians’ campaigns to access reservation housing. It would be a mistake to read medical officials’ interventions in these ongoing debates as agreed statements of policy or practice, as Jemima Pierre has done for Ghana.Footnote 99 Colonial administrators in Nigeria (and in Ghana a few years later) succeeded in framing racial segregation as chiefly a political issue that fell within their purview, rather than that of medical officials.Footnote 100

Nevertheless, high-ranking white British administrators still claimed the right to define and regulate standards at reservations and, as a result, these standards continued to incorporate tacitly racialised content. This was reflected in the views of J. G. Pyke-Knot, the secretary of the eastern provinces, who in 1950 wrote of reservations: ‘(a) There should be no discrimination on grounds of race; (b) The standard to be aimed at should be that of the Senior Government Service’.Footnote 101 Pyke-Knot condemned explicit racial exclusion, but affirmed that standards should continue to be those of ‘the Senior Government Service’, which had been established, and was still led, by white British officials. British administrators proved unwilling to consider that standards rooted in their own norms would be tacitly racialised. Rather, they presented them as neutral standards appropriate for modern forms of statehood and urban space.

Debates about reservations within British officialdom testified to the late colonial state's growing plurality, but they were not, in this instance, characterised by a triumph of specialist colonial officials. British administrators distanced themselves from explicit racial exclusion, although they still claimed the authority to set and enforce standards rooted in their own norms, which invariably incorporated tacitly racialised content.

Nigerian domestic servants

Nigerian domestic servants, their relatives, and friends formed another group that actively negotiated state, space, and race at Ikoyi. Reservations were unhomely spaces for servants and their families.Footnote 102 ‘Life can be pretty lonely in white men's compounds. No one talks to you and you must not make noise’, as Cordelia, a cook's wife, observes in a 1939 scene from Buchi Emecheta's 1979 novel The Joys of Motherhood.Footnote 103 Servants’ family and friends therefore came to live at Ikoyi, defying the reservation's explicitly racialised regulations in an effort to make life there more congenial. In so doing, they widened access to the late colonial state's resources, including housing and utilities. However, these non-elite Nigerians proved less able to contest tacitly racialised experiences of statehood and space.

Servants’ main resource in their challenge to Ikoyi's regulations was that they comprised most of the reservation's residents. Each European household, which comprised a single colonial official, or sometimes an official and his wife, employed around three Nigerian servants, who lived in quarters behind the employers’ bungalows.Footnote 104 A 1931 census suggests that the Ikoyi reservation had a population of 908, which included only 234 ‘non-Africans’.Footnote 105 These figures probably underestimated Ikoyi's Nigerian population by excluding unauthorised residents.Footnote 106 Historians have noted in passing reservations’ large African populations, but have rarely explored in detail how they shaped experiences of these spaces.Footnote 107 The large number of Nigerian servants, their family, and friends at Ikoyi meant that they influenced patterns of everyday life at the reservation, which afforded them some leverage over relationships between state, space, and race.

The unauthorised residence of servants’ wives, children, and friends in servants’ quarters challenged British officials’ original vision of Ikoyi as an explicitly racialised space with as few Nigerian residents as possible. Colonial authorities provided servants’ quarters to facilitate the work of male domestic staff, and expected their families to live elsewhere in Lagos. The unauthorised residence of servants’ family and friends showed how these Nigerians took the initiative to make life at Ikoyi more convivial. They undermined the colonial state's racialised distribution of resources by making the servants’ quarters buildings and their utilities, which included better access to piped water than in many parts of Lagos, available to more Nigerians.Footnote 108

These agendas are clear from inspections of servants’ quarters. One search in 1937 found seven men, two women, and two children in quarters intended for around three male servants.Footnote 109 European householders’ complaint letters, which often focused on Nigerian children, also document the presence of servants’ family members at Ikoyi, and their contravention of expected standards of behaviour. The colonial official G. Darby in 1937 protested about ‘African women and children living in one or other of the compounds adjacent to mine’. Despite the regulations excluding Nigerian children, Darby complained that he had ‘been disturbed by crying at every hour of the twenty-four’.Footnote 110 Colonial authorities received many similar complaints over a long period. N. Rasmusson, an agent of the Lagos Timber Company who lived at Ikoyi, protested in 1944 ‘about the noise caused by children of domestic servants’, and asked the government ‘to enforce the restrictive covenant in the lease which forbids the residence of non-Europeans other than … domestic servants’.Footnote 111 Clearly, more Nigerians lived at Ikoyi servants’ quarters than the regulations had intended.

Perhaps surprisingly, the servants won the support of some influential colonial administrators. Governor Bourdillon in 1937 dismissed Darby as ‘an officer of decidedly old-maidish tendencies’, and the chief secretary ignored Rasmusson's concerns in 1944.Footnote 112 ‘Government does not propose to amend existing leases but the restrictive covenant … will not be enforced’, he ruled.Footnote 113 This extraordinary response reflected colonial administrators’ growing scepticism about medical arguments for racial segregation, as well as their self-interest. As one noted in 1947, ‘it is often more satisfactory for an employer to allow the family of his servant to reside on the premises, for reasons of health, convenience and efficiency’.Footnote 114 Permitting servants’ families to live in Ikoyi meant that servants were more likely to be nearby when householders required them, and were considered less likely to carry disease to Ikoyi from poorer districts of Lagos.Footnote 115 The initiative of servants, their families, and friends helped to dismantle explicitly racialised regulations regarding Nigerian women and children.

The late colonial state's recruitment of more white British officials from the later 1930s, and the construction at Ikoyi of flats to house them, also brought more Nigerian servants to the reservation. They lived in larger groups at the flats than elsewhere in Ikoyi, as all servants working at each block of flats lived in a single servants’ quarters building, rather than in smaller, separate buildings located behind each employer's bungalow. This made it harder for British householders to regulate servants’ quarters at the flats, and allowed servants more freedom to live in ways they found comfortable. This is lavishly documented in complaint letters. C. L. Southall, who lived at one of the first blocks of flats, protested in 1941 about ‘a squealing infant’, and suggested that ‘if no steps are taken the flats will be occupied by 70-80 Africans & 16 Europeans’.Footnote 116 Southall was probably exaggerating, but his letter suggests the success of servants’ family and friends in taking up residence at the flats.

Complaints multiplied as more blocks of flats were completed after 1945. One letter, written by F. H. A. Bex in April 1949, was unusually long, but included many frequently cited grievances. He complained that ‘servants keep chickens & ducks, entertain guests noisily & make themselves objectionable to anyone complaining’. Bex noted that ‘half the servants’ quarters are out of sight of the flat to which they belong & therefore outside its control’, and criticised the overcrowding of rooms ‘fit for the occupation of 2 persons’. ‘A lot of noise is caused by those who have a wife & 3 or 4 small children’, he continued, adding that ‘brothers and friends are allowed to live there’.Footnote 117 These letters elaborated anxieties that Nigerian servants were succeeding in remaking relationships between state, space, and race at Ikoyi, and were indeed offering a more thoroughgoing challenge to British officials’ racialised expectations than residents who were educated Nigerians or migrants to Nigeria. ‘This particular compound … is becoming much like an African village and affords no peace for Europeans who like to spend some of their time in their own homes’, concluded Joan Saint, another resident of the flats, in a 1947 letter about noise from nearby servants’ quarters.Footnote 118

Nevertheless, even as British officials retreated from explicitly racialised regulations, tacitly racialised hierarchies remained extremely important to non-elite Nigerians’ experiences of Ikoyi. Lamidu Omomeji, a nine-year-old boy, went to pick cashews in the garden of an Ikoyi bungalow in May 1954. The householder, the British assistant superintendent of police, took his air rifle and shot Omomeji, hospitalising him.Footnote 119 The police officer was reprimanded, but escaped prosecution.Footnote 120 This shocking incident, and the limited consequences for the officer involved, suggest that despite the late colonial retreat from explicit racial segregation, in practice white British officials still claimed a tacitly racialised authority to define and enforce standards at Ikoyi.

Nigerian servants, their relatives, and friends had little to gain from racialised standards at Ikoyi and challenged them through their patterns of everyday life. They successfully overturned British officials’ prohibition on Nigerian women and children living at Ikoyi, secured better access to state resources, and thus actively forged a late colonial state. These Nigerians challenged British officials’ implicitly racialised conceptions of proper standards, but were ultimately in too weak a position to overturn them completely, as shown by the violent response to Lamidu Omomeji and the minimal consequences for the perpetrator.

Conclusion

A focus on Ikoyi shows in unprecedented detail when and how segregationist policies changed in Nigeria. At Ikoyi, a wide range of actors renegotiated constructions of space and race, contributing to the wider emergence of a late colonial state. This involved non-elites as well as elites: late colonial state-building was not only a top-down process. Attention to changes in segregationist policy and practice sheds new light on the emergence of late colonialism, and vice versa.

Ikoyi highlights the role of race and space in the making of a late colonial state. Disputes about reservations forced late colonial authorities to disavow explicitly racialised forms of statehood and space, a seismic shift that undercut the foundations of colonial rule. But these debates were less successful in addressing the continuing purchase of implicitly racialised standards. Educated Nigerians and migrants focused on dismantling explicit racial segregation at Ikoyi, winning access to reservations, and British administrators ditched explicitly racialised standards as they became a political liability. But these groups offered no sustained challenge to the institution of the reservation itself, the planning and regulation of which were informed by white British officials’ racialised ideas about statehood and space. Educated Nigerians, migrants to Nigeria, and British officials alike found it difficult to interrogate implicit understandings of racial difference that remained important to experiences of Ikoyi. Nigerian domestic servants, their family members, and friends posed the most comprehensive challenge to tacitly racialised standards of statehood and space, but wielded insufficient power to overturn them.

So the dynamics of negotiating a late colonial state at Ikoyi did not bequeath independent Nigeria decolonised, postracial forms of statehood or space. Rather, they foreclosed the opportunity of assessing from first principles the kinds of state and urban space best suited to a soon-to-be independent country. Reservations like Ikoyi exemplified the way postcolonial Nigeria inherited forms of statehood and space that remained shot through with tacitly racialised standards and colonial-era logics. It is no coincidence that Ikoyi repeatedly featured in the musician-activist Fela Kuti's 1970s critiques of postcolonial Nigeria, which he saw as stymied by an enduring ‘Ikoyi mentality’.Footnote 121

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the help of the archivists who made this work possible. I would also like to thank Ruth Craggs, Richard Reid, and the editors and two anonymous readers for their comments on earlier drafts of this article; and am grateful for the engagement of seminar and conference audiences at the Free University of Berlin, the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London, Keele University, Northumbria University, the University of Lagos, the University of Oxford, and the University of Vienna. Initial research in Nigeria was generously supported by Leeds Beckett University, and subsequent research in Nigeria and Sierra Leone by the John Fell Fund at the University of Oxford (grant 0005072).