Confusional states in older patients on general wards are common. A recent meta-analysis showed high mean prevalence rates for dementia (31%) and delirium (20%) in those patients (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). These disorders are associated with poor treatment outcome: increased mortality, greater length of stay, loss of independent functioning and higher levels of institutionalisation (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). They are very distressing for the individual and can cause difficulties for ward staff. Prompt and effective management is therefore essential to improve the condition of the individual. Unfortunately, all too often there are inconsistencies in approaches to management of confused older patients (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). Therefore, the Division of Mental Health of the Gwent Healthcare NHS Trust developed evidence-based guidelines on the management of confusion in older people on general hospital wards (Gwent Healthcare NHS Trust, 2005). Following their publication, the guidelines were sent to all general wards for reference. They were also posted on the Trust's intranet.

The guidelines were produced by members of the older adult psychiatry directorate and are intended to compliment input from the nurse specialist-led liaison mental health services for older people at the Royal Gwent and St Woolos hospitals in Newport. This service adopts the kind of proactive approach recommended by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2005). The guidelines provide information on the diagnoses of dementia and delirium, and on the assessment and management of a confused older person. It is emphasised that, where possible, the underlying cause should be addressed and that drug treatments should not be used routinely. Where agitation is a feature, and requires drug treatment, low-dose atypical antipsychotics (amisulpiride or quetiapine) or the benzodiazepine lorazepam are recommended. There is also clear advice on when input from the liaison mental health services for older people would be appropriate.

To assess dissemination and knowledge of the guidelines among junior doctors, the following audit standards were agreed:

-

1. All general wards should have a copy of the guidelines easily accessible.

-

2. All junior doctors should be aware about the Gwent Healthcare NHS Trust's guidelines. Junior doctors include foundation programme doctors, senior house officers, staff grades and specialist registrars.

Method

The initial audit was conducted in March 2006 and consisted of two parts. First, there was a survey of the wards in two local general hospitals (medical, surgical and accident and emergency (A&E)) to see whether the guidelines were displayed or available there. Second, there was a face-to-face survey of junior doctors to assess their awareness of the guidelines. Data were also obtained regarding each doctor's seniority and department, the date they joined the trust, whether they had treated a confused older person in the last month, their preferred drug treatment for agitation and the sources of information they used for guidance on the treatment of confusion in older patients. The same method was used for the second audit 6 months later (following the implementation of an action plan).

Results

Results of initial audit

Availability of guidelines on the wards

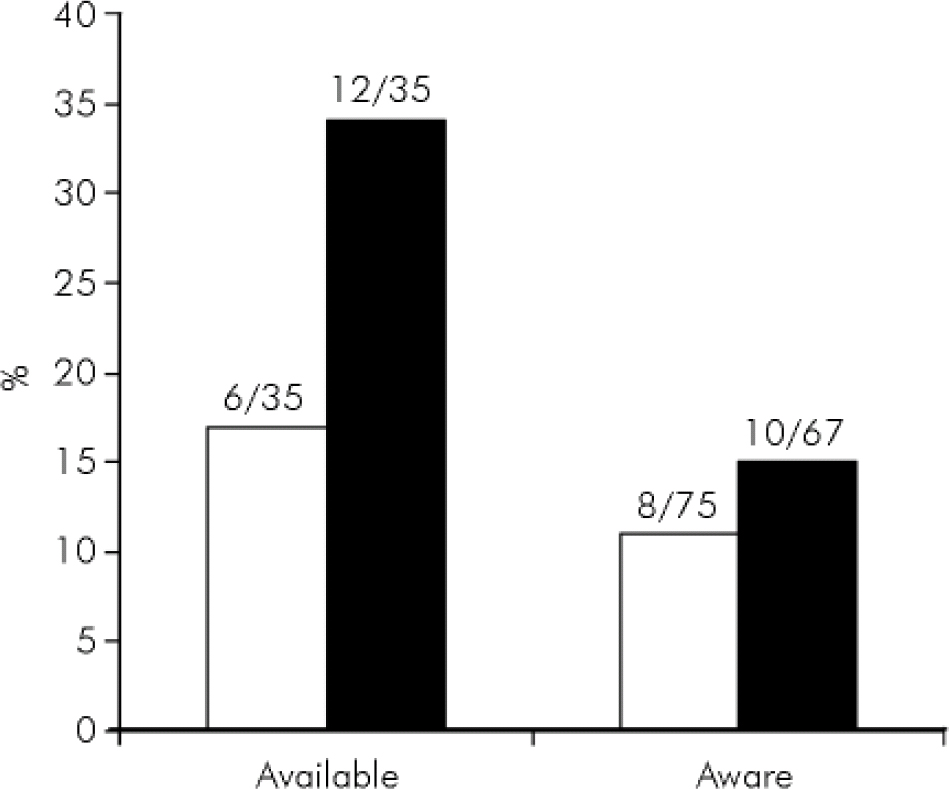

Thirty-five wards were surveyed, 31 at the Royal Gwent Hospital and 4 at St Woolos Hospital. The guidelines were available on six wards (17%) and displayed on only one ward (Fig. 1). On 5 wards the guidelines were in the ward office (usually filed). On 8 wards (23%) staff were aware of guidelines but could not find them. On 21 wards (60%) staff were unaware that the guidelines existed.

Junior doctors’ awareness of the guidelines

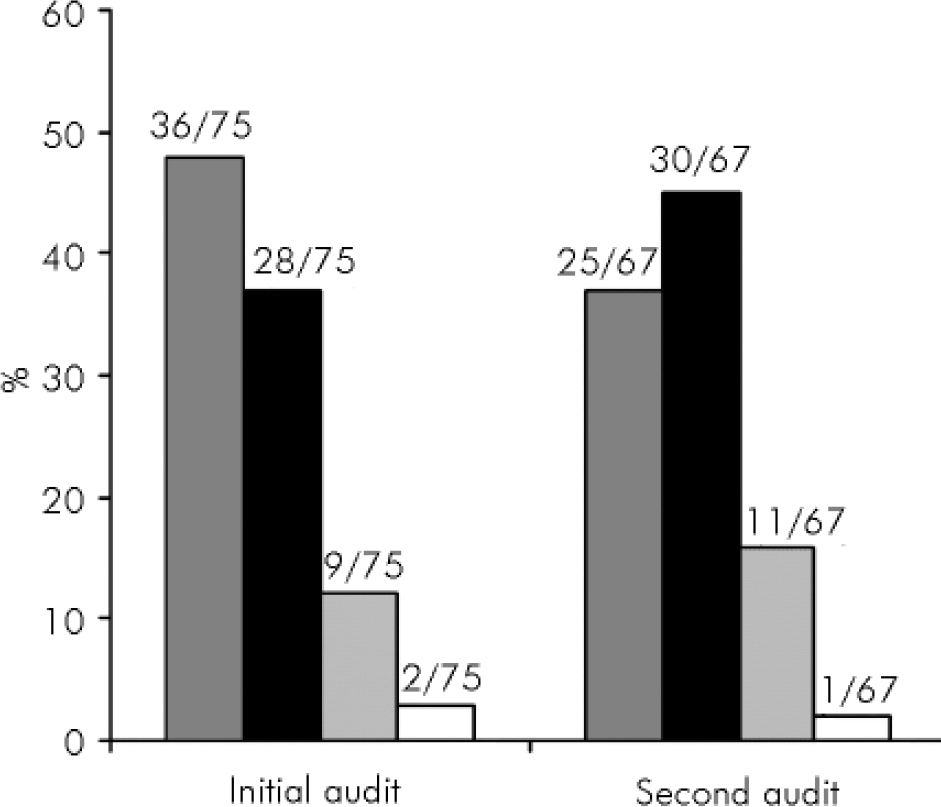

Seventy-five junior doctors were surveyed, of whom 39 (52%) worked on medical, 23 (31%) on surgical and 13 (17%) on A&E wards. There were 18 foundation programme doctors (24%), 36 senior house officers (48%) and 21 specialist registrars/staff grade (28%). Fifty-nine of the doctors (79%) had managed confusion in an older person in the past month – 90% of medics, 65% of surgeons and 70% of A&E doctors. The most commonly prescribed drug for agitation was haloperidol followed by lorazepam and then diazepam (Fig. 2). Doctors used a variety of sources of information for guidance on management of confusion in an older patient – the British National Formulary (BNF, 72%), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 17%) guidance, the Trust's intranet (16%), Royal College of Physicians (8%) and other (3%). When asked directly, 8 doctors (11%) said they were aware of the Trust's guidelines (Fig. 1).

Action plan

An action plan was devised to address the unacceptably low levels of availability and awareness of the guidelines. Hard copies of the guidelines were taken to the audited general wards by the liaison nurses from the mental health services for older people and given in person to the nurse in charge. It was also arranged that the mental health services for older people had a stand at the junior doctors’ induction in August 2006. It was hoped that a face-to-face discussion with junior doctors would increase awareness of the guidelines included in the induction pack. Additionally, the initial audit was presented at a department of medicine audit meeting in April 2006 as well as a department of psychiatry audit workshop, both of which were attended by consultant and trainee physicians of all grades.

Results of second audit

Availability of guidelines on the wards

After 6 months the same 35 wards were surveyed again. The guidelines were available on 12 wards (34%), compared with 6 (17%) previously (Pearson χ2=2.69, P=0.1). They were displayed on 7 wards (Fig. 1). On 5 wards (14%) the guidelines were easily accessible in the ward office. On 16 wards (46%) staff were aware of guidelines but could not find them and on 7 wards (20%) staff did not know about the guidelines.

Fig. 1. Availability of the guidelines among 35 wards and awareness of them among the junior doctors surveyed. □, Initial audit; ▪, Second audit.

Fig. 2.

Doctors’ drug of choice for management of agitation.

![]() , Haloperidol; ▪, Lorazepam;

, Haloperidol; ▪, Lorazepam;

![]() , Diazepam; □, Other.

, Diazepam; □, Other.

Junior doctors’ awareness of the guidelines

This time, 67 junior doctors were surveyed, 40 medical (60%), 16 surgical (24%) and 11 A&E (16%). Twenty-four of them (36%) were foundation programme doctors, 32 senior house officers (48%) and 11 staff grades/specialist registrars (16%). There were 47 doctors (72%) who had managed confusion in an older person in the past month – 82% of medics, 44% of surgeons, 73% of A&E doctors. The most commonly prescribed drug for agitation in the older patient was lorazepam followed by haloperidol and then diazepam (Fig. 2). There was no major change in the sources of information reported – BNF (60%), NICE guidance (13%), the Trust's intranet (18%), Royal College of Physicians’ guidance (1%) and other (7%). When asked directly, 15% of the doctors said they were aware of the Trust guidelines, compared with 11% in the initial audit (Pearson χ2=0.58, P=0.45) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, these were all medics, which meant that 33% of the medics knew about the guidelines, as compared with 15% of medics in the initial audit. Of the 67 doctors, 35 joined the Trust in August and probably attended the induction. Of these 35, only 4 (11%) were aware of the guidelines.

Discussion

This audit stemmed from a real-life discussion that raised two key questions: were the Trust guidelines for the management of confusion in older patients available on general wards, and did junior doctors know they existed? The initial audit revealed that the guidelines were available on very few wards visited and that the majority of junior doctors surveyed were unaware of the guidelines. This was reflected in the doctors’ most commonly reported choice of medication for the pharmacological treatment of agitation.

An action plan was formulated to tackle these issues. It seemed sensible to re-distribute guidelines to the wards and this was done in person by nurses from the mental health services for older people liaison team. In addition to presenting the audit results at department of medicine audit meetings and department of psychiatry audit workshops, it was felt that the obvious way to target junior doctors and improve awareness of the guidelines was address them at their induction day.

The second audit revealed that what seemed like a reasonable action plan had a fairly small impact. Guidelines still were not displayed on the wards. This raises important questions about the way information is managed on wards and brings into doubt the value of sending hard copies to the wards as a means of disseminating guidelines and policies. Participation in the junior doctors’ induction did not have much effect on awareness of the guidelines. This may be due to ‘information overload’ at the time of induction. That said, the second audit results showed that the prescribing habits changed and that the guidance could be disseminated indirectly (e.g. by doctors ‘mirroring’ the prescribing habits of others in their team).

Spreading change in healthcare services

Berwick (Reference Berwick and Berwick2004) characterises people who adopt innovations in healthcare as ‘early adopters’, ‘the early majority’, ‘the late majority’ and ‘laggards’. Early adopters are opinion leaders, locally well-connected, who cross-pollinate and select ideas that they are interested in trying out. They are self-conscious experimenters and, most importantly, they are observed by other members of the clinical group. In particular they are watched by the early majority – more locally focused, but keen to keep abreast of and experiment with innovations. Berwick notes that the spread of an innovation has a tipping point at around 15–20% adoption, after which it becomes difficult to stop the spread of change. For this to occur, it is essential to engage the early adopters and to enable them to interact with the early majority.

With reference to our audit, we feel it is important to continue participating in the junior doctors’ induction but additional strategies will need to be developed, aimed at targeting early adopters who can facilitate the spread of change. We plan to review and revise the guidelines following an up-to-date review of the evidence base, and in light of the new Mental Capacity Act 2005, with input from consultants and other doctors from the Gwent Healthcare NHS Trust department of medicine for the elderly. In addition we aim to provide teaching sessions on the management of confusion in older patients as part of the local postgraduate medical education programme. Another strategy will involve asking ward pharmacists to monitor prescribing to agitated confused older people on general wards, with feedback to the prescribing doctor including reference to the guidelines where necessary.

Conclusion

Our finding that completing one audit cycle did not bring about major change is not unique (e.g. Reference Crossnan, Curtis and OngCrossnan et al, 2004) and it highlights the importance of a second audit. By completing the audit cycle we have been able to revise our action plan taking into consideration the factors influencing change in healthcare practices. A further audit will be carried out, to ensure that the necessary changes eventually take place.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr Jonathan Bisson for assistance with the statistics.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.