In 1972, a 30-year-old Christopher Ballantine, having recently graduated from Cambridge University and written some journal articles and a column for the British weekly New Society, took up a position in the newly founded Department of Music at the University of Natal. Two years later, Ballantine assumed the role of head of department where, at his insistence, the experimental composer Ulrich Süsse had already been hired to set up the first university-based electroacoustic music studio in Africa, the centrepiece of which would initially be a state-of-the-art modular synthesizer. The music department in Durban was to be avant-garde.

The synthesizer was imported through Mike Hankinson, working as a music producer in Johannesburg and as Boosey & Hawkes's agent in South Africa at the time. One could say that Hankinson was an authority on electronic music: in 1971 he released one of the first synthesized classical albums and went on to produce a series of synthesized covers of popular 1970s radio hits.Footnote 1 This was not quite what the department had in mind, though. Instead of the EMS VCS-3, the portable and user-friendly synth Hankinson had recommended and was familiar with, they opted for the ARP-2500 also used by Süsse's teacher Elias Tanenbaum at the Manhattan School of Music in New York. Touted as ‘The Concert Grand of Synthesizers’, ARP manufactured only 100 of these models, favoured by Ivy League music departments in the United States (Figure 1). Princeton, Brown, and Yale had one. And now Natal had one too.

A grossly unequal society is immoral at any time. In our time it is also stupid. We can no longer afford the waste of resources involved. We can no longer afford to stifle creativity, inhibit cooperation, and foster fierce and destructive competition for scarce goods.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)

Figure 1 Promotional material from a 1972 brochure titled ‘The ARP 2500 Electronic Music Synthesizer’.

The ARP-2500 was a complex, reliable, and flexible system designed by a former NASA electrical engineer. It was also bulky, cumbersome, unintuitive to operate, and unsuited to live performance.Footnote 2 Süsse, born in Germany in 1944, had studied composition with Karkoschka, Stockhausen, Ligeti, and Berio, but had limited know-how of (or interest in) the technical side of electronic music composition; like his teachers and peers in Europe and New York he had relied on a technician. Without access to ARP's service network or the help of a trained local technician, he had no support in navigating the ARP's steep learning curve. In 1975, Süsse decided that if he wanted to continue his career in South Africa, he would have to learn to operate the machine. He applied to spend time in the ARP factory in Boston, but his request was denied. Despite its central role in the mythology of the founding of the music department in Durban,Footnote 3 the ARP-2500 was, for Süsse, more white elephant than black box.Footnote 4

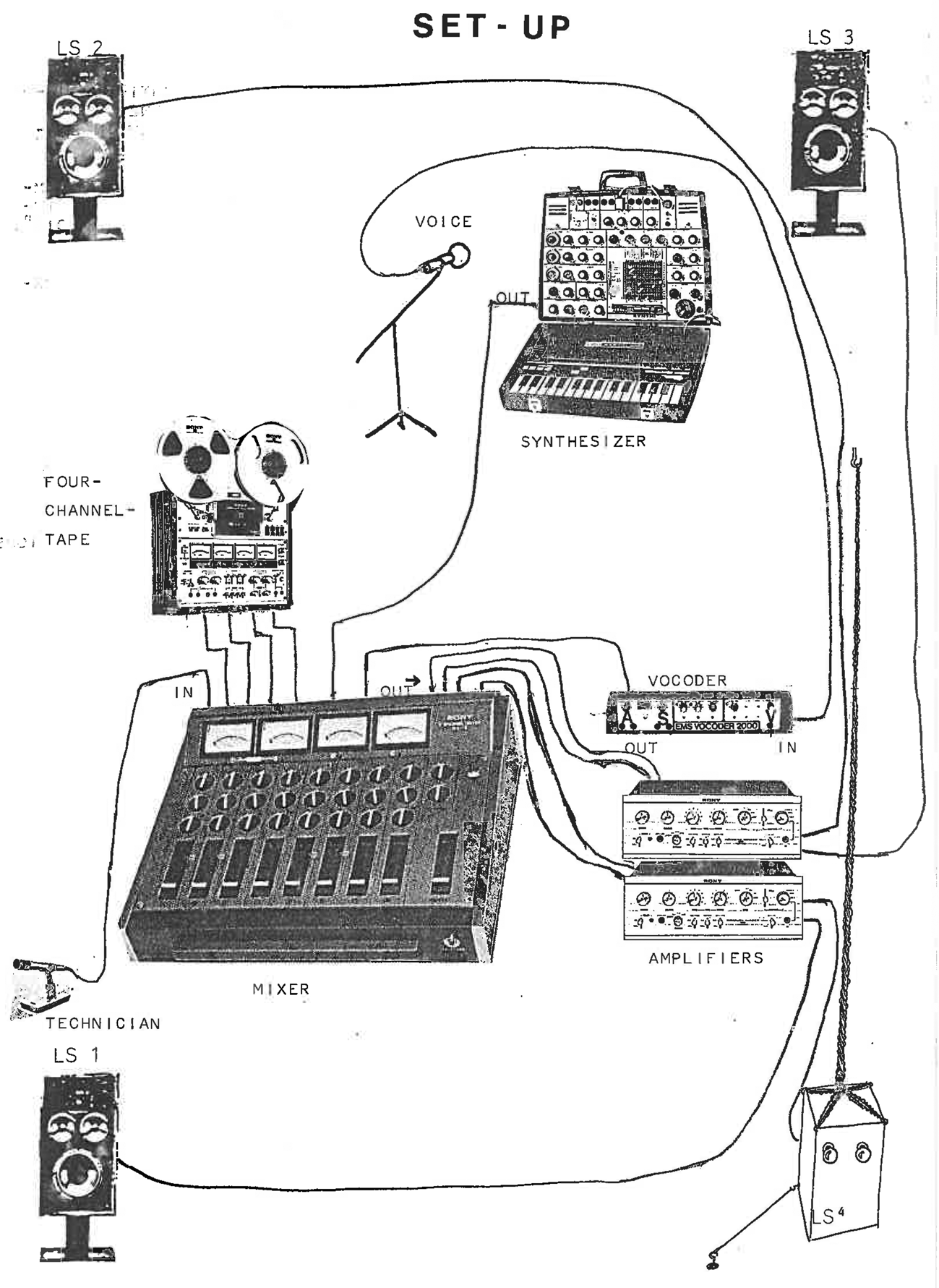

Süsse returned to Stuttgart in 1976. As the set-up sketches for his composition Ear oder Ohr (1979) attest, he continued his work on an EMS VCS-3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Ulrich Süsse, Ear oder Ohr (1979).

This is not to say that Süsse and Ballantine did not attempt to overcome the technological dilemma of being avant in Africa. In the early years of the electronic music studio, they enlisted colleagues in the physics department to assist in troubleshooting their technical problems with the ARP and to build new equipment for the studio. By that time, the studio had a synth and a tape recorder but no mixer, and when the physics department offered to build one, Süsse wrote to Tanenbaum in New York who provided him with detailed sketches for a mixer with twelve inputs and four outputs. The machine was returned with twelve outputs and four inputs.Footnote 5

The collaboration between the music and physics departments continued, despite these mangled results. Modelled on Stockhausen's improvisation group in Cologne, Süsse and Ballantine formed a ‘New Music Group’ with musicologist Dale Cockrell (vocals) and physicists Don BedfordFootnote 6 (trumpet) and Derrick Wang (technician) (Figure 3). The New Music Group staged concerts of avant-garde and experimental music as well as live improvisations on acoustic instruments with electronic interventions.Footnote 7 Working with scientists was more than a practical matter; it infused the group's activities – and, by extension, that of the fledgling music department – with an aura of scientific discovery.

[On] the organizational level we must ensure that all organizations we work in prefigure the future. Organizations must be participatory rather than authoritarian. They must be areas in which people experience human solidarity and learn to work with one another in harmony and in love.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)

Figure 3 The Durban New Music Group c. 1975, featuring (top and from left to right) Christopher Ballantine, Ulrich Süsse, and Dale Cockrell. Photographs courtesy of Christopher Ballantine.

In his 1977 essay ‘Towards an Aesthetic of Experimental Music’ published in The Musical Quarterly, Ballantine described one of the group's improvisation sessions at some length. Arguing that an ‘open-minded’, ‘open-ended’, ‘future-oriented’, and ‘scientific’ frame of mind was one of the ‘central irreducible features of experimental music’,Footnote 8 he explained the significance of the ‘experiment’ as a ‘discovery … in something approaching the natural-scientific sense’:

Four musicians, all with experience in contemporary improvisation, and all of whom had played together on previous occasions, undertook to perform a group improvisation in circumstances where no player could hear any of the others. Each player, with his instrument(s), was closeted alone in a room remote from those of the other players; microphones and contact microphones fed the sound produced in each room to a small auditorium where the total sound was recorded on a four-channel tape recorder (one channel for each player) and simultaneously played to an audience through four independent loudspeakers. There were absolutely no guidelines for the improvisation, except to play ‘musically’ and to attempt to ‘commune’ inaudibly with the other players; apart from this, the players had deliberately avoided discussing anything beforehand (including the approximate length of the performance).

…

The performance ended spontaneously after seventy-five minutes, fifteen minutes after the first player had stopped. The audience – and the players, on hearing the playback – were amazed. The composite improvisation was an unqualified success in musical terms: the musicians seemed unerringly to be playing as a group, responding to each other with what appeared to be uncanny sensitivity. That each single player had improvised well was not in doubt and not surprising; but that the playing of the four simultaneously made a ‘piece’ of such unfailing musical sense seemed to defy explanation.Footnote 9

After the event, the tape recording was subjected to further experimentation. The individual channels were re-recorded with differing time delays between the start of individual improvisations. They found that ‘each new combination yielded fresh musical significance and continued to make good musical sense’. Ballantine concluded that the explanation for this synchronicity ‘lay in the nature of the idiom’ that was ‘free of pregiven content’ and thus ‘more adaptable, more amenable to rearrangement, and more open to everchanging significance being vested in it, than any earlier Western music’.Footnote 10

The spirit of experimentalism in which the music department was founded was, for Ballantine, rooted in a Marxist intellectual tradition and infused with ideas derived from post-1968 British counterculture. Ballantine was at Cambridge in the late 1960s, and although Virginia Anderson has described the British 1968 experience as ‘conservative, isolated and politically untouched’,Footnote 11 he was profoundly influenced by the events of May 1968 and actively involved in the alternative student movement:

1968 was a brilliant time, brilliant, brilliant. To be a student in the northern hemisphere then was just thrilling; to have lived through May/June ‘68 was really a life-changing experience: it was then that I started to get very seriously interested in Marxism … I encountered the Frankfurt School and Adorno, and ate breathed and slept this stuff.Footnote 12

As opposed to the violence and rioting that marked student protests in France and West Germany, students at Cambridge modelled their activism on British underground culture. Ballantine, who was close friends with the Cambridge critical social theorist Paul Connerton, was part of an initiative that set up an ‘Arts Lab’ in a basement space in Cambridge and an ‘Antiuniversity’ at King's College, where they staged events, hosted guest speakers, and practised alternative forms of art.Footnote 13 The countercultural scene in the UK, in tune with the global suspicion for establishment values, provided the impetus for anarchist forms of institutional thinking. The Arts Lab movement, founded in 1967 by Jim Haynes in London's West End, was a collective concerned with creating ‘complete anti-institutional cultural environments’ that challenged formal divisions between the arts, and displayed, according to Maggie Gray, ‘an overarching commitment to indeterminate, unconstrained, and collective practice’.Footnote 14 An Arts Lab was to be a ‘non-Institution’, an ‘energy centre’, a ‘commune situation’ and a ‘multi-purpose space’ where people ‘lived and worked together’ and where ‘anything and anyone might happen’.Footnote 15 Similarly, the Antiuniversity of London, founded in February 1968, viewed itself at the vanguard of a network of countercultural ‘anti-institutions’ that ‘emerged from an apparent consensus, among many branches of the counter-cultural network, that through radical cultural activities and experiments a new society would emerge in which the “square” state would become unnecessary and eventually wither away’.Footnote 16 ‘The schools and universities are dead’, wrote psychiatrist Joseph Berke in April 1968 in an introductory text about the Antiuniversity:

They must be destroyed and rebuilt in our own terms. These sentiments reflect the growing belief of students and teachers all over Europe and the United States as they strip aside the academic pretensions from their ‘institutions of higher learning’ and see them for what they are – rigid training schools for the operation and expansion of reactionary government, business, and military bureaucracies.Footnote 17

If at Cambridge Ballantine encountered a music department that ‘was really very conservative, very very conservative. There was nothing interesting happening. It was all old-style positivistic musicology’,Footnote 18 he also encountered and was profoundly influenced by a set of cognate practices and movements that collectively asked: ‘How can we do things differently?’; a Marxist, 1968-informed, anti-institutional sensibility that would infuse his (de)institutionalization of music in Durban:

My commitment was going to be to try to find a way to make music in a South African context participate in the struggle. I understood that to be partly through the writing that I was doing and also partly through being in on the ground floor of what was going to be a new musical institution; it wasn't shaped … there was nothing to fight against, except what I wanted to engage with, which was a capitalist world and race capitalism.Footnote 19

[T]here is one major area of political work where [white liberals] are perhaps best equipped to work. This is, as proponents of black consciousness have pointed out, in the area of changing white consciousness. It is vitally important to analyse the ways in which whites oppress themselves, and to devise ways of bringing home to them the extent to which the pursuit of material self-interest empties their lives of meaning.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)In ‘Towards an Aesthetic of Experimental Music’, Ballantine inserted the improvisational experimentalism of the New Music Group in Durban into a European intellectual genealogy of ‘such radical thinkers as Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, and Theodor Adorno’ and within the artistic context of the British and American experimentalists: figures such as John Cage, Frederik Rzewski, Alvin Lucier, LaMonte Young, and Cornelius Cardew. Writing against the ‘the detractors of experimental music … who speak from a left-wing position’, Ballantine wanted to show that the theory and practice of experimental music, in fact, ‘derive from, and support such a position’.Footnote 20

The erroneous misalignment between experimentalism and left-wing criticism was the result of a ‘simplistic – and possibly ideological’ focus on ‘explicit content’ as opposed to an understanding of artists as agents in the production process, argued Ballantine.Footnote 21 This, in a reading of Benjamin, had to make way for a view of art concerned with the decay of the ‘aura’ of the work of art and with improving its ‘apparatus of production’ by turning ‘readers and spectators’ into ‘collaborators’.Footnote 22

Ballantine proceeded to outline the principles of musical experimentalism that could result in ‘improving the apparatus of music's production’ and the ‘desacralization of art’: increased participation between audience and musicians, bringing together skilled and unskilled players, a quasi-scientific attitude of discovery inherent in improvisation, removing the distinction between life and art, emptying sounds of their significance, and ‘the studied degradation of material that is Dada’.

In making this connection between musical experimentalism and the Left, Ballantine was again tapping into British counterculture and his earlier experiences at Cambridge. So-called ‘high-art’ experimentalists such as Cage and Cardew ‘not only influenced the British Underground’, writes Anderson, ‘but were among its primary artistic figures’.Footnote 23 Cardew was, in fact, one of the founding members of the Antiuniversity where he ran collective and experimental sessions in artistic creation, thereby highlighting the providence of alternative arts practices in the practical re-imagining of educational and social institutions in the late 1960s.Footnote 24 Improvisatory experimentalism, especially when it incorporated new sound technology, was seen as an avenue towards the expansion of consciousness. As Ted Gordon observes, ‘Tape, like psychedelic drugs, promised an expansionary effect: it allowed musicians to play with a revolutionary, experimental openness that seemed to mirror the larger political and cultural shifts of the decade.’Footnote 25 Ballantine recalls such an ‘improvisatory high’, during a performance by Stockhausen at London's Round House in 1969 – a performance he describes as ‘one of the most memorable musical experiences’ of his life, and one that led to him and his group of friends at Cambridge to form an improvisation group of their own, clearly a forerunner to the New Music Group in Durban :

The audience was seated in circles. Stockhausen was in the middle wearing his white garb, as usual, and controlling everything. The sounds were all mixed, and the experience was listening to sounds moving through space. And the sense that you had of these sounds moving across space and around your head and meeting each other, colliding and joining and separating in the most wonderful, glorious way, was just absolutely thrilling.Footnote 26

Although the music department at Cambridge showed no interest in experimentalism at the time, and the ‘New Musicology’ would take at least another decade to catch on to the Marxist impulse already prevalent in sociology in the late 1960s, Ballantine saw the potential for leftist-inspired experimentalism in rethinking musical scholarship and of ‘frequent involvement with the progressive (questioning, socializing) aspects of experimental music’ in inculcating ‘desirable new habits of perception, expectation, and response in audiences’:Footnote 27

This was the environment (at Cambridge): It was Stockhausen. It was the Beatles. It was the hippy movement. It was Marx. It was 1968. It was Adorno. It was Horkheimer. It was the Frankfurt School. It was Walter Benjamin. And then, coming back to South Africa with all this stuff exploding in my head and thinking, well: How can I make this work in some small way in this new music department? And that I took to be my mission; I made that my task. And appointing a colleague such as Uli (Süsse) fitted exactly into that.Footnote 28

Ballantine would later elaborate on this practical, educational question in Music and Its Social Meanings (1984), where the intellectual genealogies he outlines earlier, are worked out theoretically in an influential text that nevertheless seemed unable to puncture the constrictive reality that critical theory, in the oddly distorted world of apartheid allegiances to Western values, was always-already co-opted into the larger project of white domination.Footnote 29

The excitement of self-discovery, the excitement of shattered certainties, and the thrill of freedom: These are experiences that are closed to white South Africans. The price of control is conformity.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)Conceived in 1974 while in Durban, Süsse's Ear oder Ohr (1979) is a conceptual piece for four-channel tape, voice (the speaker enacting the role of composer), a ‘technician’ speaking through a vocoder, prepared loudspeaker, and synthesizer (Figure 4). It pits a series of pompous composer statements about the importance of thinking versus feeling and the American and European avant-garde against the reality of soundchecks, technological failures, and the stop–start nature of experimental performances.Footnote 30 The composer statements are continuously interrupted by a malfunctioning fourth channel that the ‘technician’ – after repeated unsuccessful attempts – eventually sorts out, only for the piece to start over from the beginning. The piece ends as the anthropomorphized loudspeaker ‘unravels’, the reels of the tape machine turn within themselves, and the tape machine is unplugged.

Figure 4 Ulrich Süsse, Ear oder Ohr (1979), pp. 3–4.

Süsse recalls three remarkable reactions to Ear oder Ohr:

in Stuttgart my older colleague Milko Kelemen (1924–2018) said that he liked the piece and added ’I wish I could also write a piece like this‘ and I asked myself what keeps him from doing it…

(OK, sure I know: the European chain. Kelemen (who by the way is not known very well, but thinks of himself highly) does not write like this. Kelemen writes like t h a t and that is why he cannot write a piece like t h i s … poor fellow.)

2nd reaction: At the performance in Durban … there were architectural students sitting in the first row and the actor Peter Larlham played the role of the technician so perfect that one of the students said ‘Ouch there is all this expensive equipment and they don't know how to handle it’ (on stage was amplifying equipment, a small synthesizer and a vocoder and lots and lots of cables) … so they did directly fall into the trap. Actually I never thought anybody would, it seemed so obvious that it was a hoax with a happy ending.

OK the third reaction was more understandable … I had developed a friendship to a Zulu man, Thomas Vezi, who worked at the University and I invited him and drove him home to Umlazi which was actually illegal at the time (1979) and he felt sorry for me, that my piece didn't work.

Ballantine remembers a fourth one, which became a standing joke in the department. After the performance, a prominent English professor called out in dismay: ‘Five cents for a good tune!’

Until white South Africans come to understand that present society and their present position is a result not of their own virtues but of their vices; until they come to see world history over the last five hundred years not as the ‘triumph of white civilization,’ but simply as the bloody and ambiguous birth of a new technology, and until they come to see these things not in the past but in hope for the future, they will not be able to communicate with black people, nor, ultimately, with one another.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)Absent in Ballantine's 1977 article is any explicit consideration of the turbulent urban and institutional context of the New Music Group's activities, the South Africanist work produced by other Durban anti-apartheid intellectuals, or the political situation in South Africa at the time. Absent from the New Music Group's experimental sensibility, too, was a practical reckoning with the kind of political activism that identified not with the idea of gradual reform available to white South Africans privileged through background and education to occupy the ranks of the South African professoriate, but with the risks of openly confrontational oppositional strategies in the face of state repression. As such, the notion of ‘removing the distinction between life and art’ remained oddly unrealized in their pursuit of an experimental agenda while political repression and military escalation of South African civil society was continuing apace.

Ballantine would, though, raise the matter of radical political action six years later in his 1983 address to the Ethnomusicology Symposium, where he urged his fellow (ethno)musicologists to align themselves and their work with the progressive movements for social change, so as to produce an ‘ethnomusicology of liberation’. In this talk, titled ‘Taking Sides: Or Music, Music Departments and the Deepening Crisis in South Africa’ he predicted an escalating ‘politicization of aesthetics’ in line with what he foresaw as an ‘explosive’, brewing social unrest and the inevitable escalation of Black militancy in opposition to apartheid.Footnote 31

Given the harsh apparatus of the apartheid state at its heyday, as it sought to repress dissent in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and the Rivonia trial in 1964, Ballantine's reluctance to connect his academic writing of the 1970s to the ‘tense and conflict-ridden society’ he described in 1983 is perhaps not altogether surprising. Ballantine recalls:

In 1972 you didn't want to go around calling yourself a Marxist. I'd smuggled some books back from Cambridge. You had to declare every book you were bringing back and there were some books that I couldn't get into the country – didn't want to even try, because you then get on the security branch watch-list. But there were some books I'd managed to get in – and I can remember in 1972 or 73 – getting so nervous about what I had that I actually had a book-burning. I was keeping a whole lot of books in the ceiling of the house that I was living in.Footnote 32

Be that as it may, some white South Africans did – at considerable risk – cross the boundaries of what was ‘safe’ for them at the time: intellectuals such as Bram Fischer, Beyers Naudé, and Trevor Huddlestone (of course not South African). The choice to be careful, and act within the boundaries of the permissible in an authoritarian and repressive context, was and remains a choice contextualized by the risks taken by those less inclined to acquiesce.

As Heike Becker has pointed out, the 1960s to mid-1970s is generally seen as a ‘long period of political acquiescence’ that ‘ended only with the Soweto uprising on June 16th, 1976’ – a period when, after the banning of the African National Congress, resistance politics moved underground. Student protests were significantly stifled by harsh apartheid laws too. The Extension of University Education Act, passed in 1959, ensured that South African students were admitted to universities strictly along racial and ethnic lines, which effectively closed down opportunities for cross-racial dialogue between students that would have precipitated outright and radical protest.Footnote 33 This meant that in 1968 there was nothing in South Africa that approximated the scale and impact of global student protests, although, as historian Julian Brown has observed, the ‘road to Soweto’ was prepared by the often haphazard experimental activism of students who took their cue from workers, and vice versa.Footnote 34

The ‘Mafeje affair’ at the University of Cape Town was a notable exception.Footnote 35 When Black African scholar Archie Mafeje, who had graduated cum laude with a Master's degree from the University Cape Town, was offered a position in the Department of Social Anthropology, which was then rescinded by the university under state pressure, a group of 600 white students and some staff occupied the university's administration building and staged a week-long sit-in protest. This protest, argues Becker, mirrored the form if not the scale of international 1968 protests, and left a lasting imprint on those present.

The political events in Durban in the early 1970s that saw a rare confluence between students and workers was another. ‘If apartheid South Africa had its May 1968 or its Prague Spring’, writes Alex Lichtenstein, ‘the moment came five years late in January and February 1973, with the mass strikes that rocked the Indian Ocean port city of Durban and the surrounding province of Natal.’Footnote 36 Dubbed by Tony Morphet, in his Rick Turner Memorial lecture delivered at the University of Natal in 1990, as the ‘Durban moment’, the trade union strikes of 1973 were underpinned by four concurrent intellectual projects that converged at the university in the early 1970s. These projects included the philosophical and political work of the academic and intellectual Richard (Rick) Turner, who was appointed as lecturer in Political Science by the University of Natal in 1970 before receiving a government banning order in 1973 that prohibited him from teaching and publishing his work (although he retained his academic position); Steve Biko's theorizations of Black Consciousness (BC) and its associated community development projects; South African sociologist Dunbar Moodie's historical re-evaluation of Afrikaner history; and Mike Kirkwood's South African challenge to the English literature canon.Footnote 37 According to Morphet, these four projects formed part of an ‘atmosphere of intellectual ferment’ at the university that signalled ‘in countless details … a structural shift in the received intellectual patterns of the social world’.Footnote 38

Rick Turner studied with Sartre at the Sorbonne, and returned to South Africa in 1966. Although he was thus not directly involved in the 1968 student protests in Paris, Alex Lichtenstein argues that Turner was a central figure in translating New Left ideas from abroad to the white radical students who he attracted like ‘a magnet and gadfly’ and who, due to government censorship, were otherwise cut off from the radical movements that influenced their global peers. The leftist anti-institutional sentiment is evident in a lecture in which Turner stated:

Students don't want universities to train them to be technicians for servicing the present social machine. They want universities to be involved in the creative task of evaluating the present social machine, of exploring different ways of organizing society … All they want … is to be part of a society which actually looks for questions and answers, a society which isn't smug, whether its smugness be that of the old Czech Stalinist bureaucracy, the American influence-peddling party machine, or the white South African oligarchy.Footnote 39

‘Like the “Durban Moment” itself’, Lichtenstein argues, ‘Turner's thought synthesized a number of tendencies associated with the global New Left of the 1960s, many of which filtered only slowly into South Africa.’Footnote 40 These included Turner's New Left existentialism, his belief that social consciousness could be changed through radical and unorthodox pedagogy, and his commitment to participatory democracy in which workers’ control stood central. Additionally, so Lichtenstein notes, Turner, although he rejected mind-altering substances, was attracted to ‘alternative ways of living and loving’. Directly contravening the Immorality Act of 1950 , he fell in love with and married Foszia Fisher – who was classified by the apartheid government as ‘coloured’ – and the couple shared their house with many of his students in a commune setting in Durban. In the Durban context – crucially – Turner's New Left ideas converged with the Black Consciousness of Biko (with whom Turner had formed a close friendship) – a convergence most notable in Turner's The Eye of the Needle, a text setting out his utopian vision for a South Africa based on participatory consciousness, finished two weeks before his banning order came into effect. Turner's writings of the time presented a vision for change alongside a scathing critique of white liberalism that led, according to Steven Friedman ‘a generation of young whites to embrace a radicalism of thought and action which broke decisively with the suburban milieu in which they were raised’.Footnote 41 In contrast with the structural Marxism that dominated English liberal universities in South Africa (the Afrikaans ones, described by Premesh Lalu as ‘volksuniversiteite’, had by that time bought more-or-less wholesale into Afrikaner nationalism),Footnote 42 Turner's stance against apartheid was practical and moral and often directed at white liberals whose ‘behaviour and beliefs …constitute a striking example of precisely how deep the assumptions of white supremacy run’.Footnote 43 Drawing on the Black Consciousness manifesto of the South African Student Organization (SASO), Turner argued that a belief that ‘although blacks are not biologically inferior, they are culturally inferior’ was entrenched in white liberal thinking, and that liberalism sought ‘an assimilation of Blacks into an already established set of norms drawn up and motivated by White society’. The liberal notion ‘that “western civilisation” is adequate, and superior to other forms’, and that Blacks can, through education by whites, attain a similar level of western civilization, was deeply flawed, said Turner, especially given the destruction and moral void that belied the white march to ‘progress’. White liberalism, then, was primarily concerned with ‘relaxing certain oppressive legislations and to allow Blacks into a White-type society’ as opposed to the ‘radical’ notion that ‘“white” culture itself is at fault’, and that ‘both blacks and whites need to go beyond it and create a new culture’.Footnote 44

On Sunday evenings, when the New Music Group rehearsed, Ballantine would fetch Derrick Wang (the group's technician) from ‘The Rickory’, 32 Dalton Avenue, Bellair – the commune run by Rick Turner and his wife Foszia Fisher.

Whites are where they are in the world essentially through having developed a great capacity to wield force ruthlessly in pursuit of their own ends. That is, there is an integral relationship between the nature of the culture of the whites and the fact of their dominance in South Africa. The refusal of blacks to want to be ‘like whites’ is not racism. It is good taste.

Rick Turner, ‘Black Consciousness and White Liberals’ (1969)If Turner's main inspiration for political work in South Africa was Sartre and Biko's Fanon, Ballantine turned to the music of the Darmstadt School and the British and American experimentalists. At a moment when the apartheid government banned many literary works considered subversive, and university libraries were actively embargoing New Left scholarship,Footnote 45 Ballantine acquired for the Music Library the overtly political and absurdist scores of experimentalists such as Cornelius Cardew, Christian Wolf, and La Monte Young and performed these pieces with the New Music Group at lunch-hour concerts and events around the university campus (Figure 5). Ballantine recalls a performance of Stockhausen's Kontakte:

Can you imagine doing Kontakte to a student audience these days? We did it as a lunch-hour concert in this hall that was well-packed. It was a large hall. It was the student union, in fact, that we used. And we sat in the middle with the students sort of in chairs arranged in circles around us. And we played Stockhausen's Kontakte! And people listened! There was a real interest in that.Footnote 46

Figure 5 Peter Larlham and an unknown student in a performance of experimental music in the Howard College Theatre c. 1975. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Ballantine.

By ‘occupying’ the Student Union with experimental and avant-garde music, the New Music Group believed that they carried forward the energy of 1968 in a practical fashion at the University of Natal. In this way, the new music department emulated the Arts Lab or the Antiuniversity at Cambridge, with the difference that – in the South African context – what would have been a concerted political appeal through artistic refusal, absurdity, and ridicule would likely have escaped South Africa's knowledge police. Quoting Benjamin, and referencing La Monte Young's Piano Piece for David Tudor No. 1 – in which a piano grazes on a bale of hay until it is ‘satiated’ – Ballantine noted that ‘spasms of the diaphragm generally offer better chances for thought than spasms of the soul.’ ‘If some experimental situations are trivial or patently absurd’, he continued, ‘this may not necessarily be a bad thing, especially if one views them as experimental occasions. It is part of a scientific frame of mind to realize that experiments may fail or be inappropriate, and that there is something to be learned from these failures.’Footnote 47 And while performing artistic refusal without censure was, of course, a gratifying idea, it hardly challenged, much less changed, any of the political conditions that guaranteed (and funded) the conditions of expression realized by the New Music Group.

Nevertheless, it has to be pointed out that Ballantine's colleagues in the South African musicological fraternity shared neither his politico-aesthetic views nor his sense of humour. Ballantine was, for all practical purposes, excommunicated by the South African Musicological Society for his ‘radical’, ‘crazy’, and ‘weird’ ideas.Footnote 48 In fact, the institutionalized South African compositional ‘avant-garde’ – to the extent that it ever existed – emerged only a decade after Süsse's appointment when the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) staged its first Contemporary Music Festival in 1983. By then, the national broadcaster had somehow succeeded in negating a decade of electro-acoustic work and the considerable expertise that existed at the University of Natal, and in stripping musical experimentalism totally of its genealogy in 1960s countercultural, anti-establishment frivolity, presenting it instead as a stern affair aligned with an outdated, pre-war notion of European musical progress now in service of white nation building.Footnote 49

That the social-revolutionary potential of musical experimentalism was initially misrecognized (and, presumably, thereafter suppressed) by the South African musical intelligentsia, emerged when the SABC invited Stockhausen to present a series of live radio lectures in 1971 (Figure 6) – a year before Ballantine returned to South Africa. In the correspondence between Hans Adler and Hans Kramer, the respective chairs of the Johannesburg and Cape Town Music societies who co-arranged with Anton Hartman of the SABC Stockhausen's South African tour, Kramer wrote:

As I told you on the phone I met with [Gunter] Pulvermacher and [Richard] Behrens [the heads of music at the Universities of Cape Town and Stellenbosch]. They are both very keen to have a programme [of Stockhausen's music]. How my subscribers are going to ‘take’ this offering is a big question mark. But I feel they should be exposed to this type of ‘sound’. I don't think, honestly, that it is ‘music’.Footnote 50

As William Fourie observes, this correspondence indicates the SABC's paternalistic impetus to educate its listeners in the manners of what they saw as their Western European counterparts, even while disregarding the musical content of Stockhausen's work.Footnote 51 This strategy backfired spectacularly, though, as composer Peter Klatzow, who was working as a controller at the SABC at the time, recalls:

Stockhausen came out here in the early 1970s … to give a serious of live lectures, on air, at the SABC. And he was so highly regarded, that on the nights that he gave lectures, the entire schedule was simply put on hold so that he could talk for as long as he liked. And at some point in one of his pieces he was talking about how the materials actually come together and blend. And he said ‘This is integration and this is what I promote and things are only interesting when they mix’, you know, ‘the purity of this, the purity of that, is not interesting, what it becomes when the blend has happened, that is what is interesting and what I'm looking for.’ And this was terrifying the senior director who I could see sitting in the front row of the lecture hall. He was looking up at the control room saying ‘Cut! Cut!’ with his hands. ‘Stop this! Don't broadcast this!’. And I looked at the controller (James Williams) and I said: ‘I am looking at you because there is something down there that I can see that I don't like very much, and I think we just have to ignore it’. So the controller and I were looking at each other determined not to look down into the auditorium where the director was indicating ‘Cut! Cut! Stop! Don't let this be broadcast!’. Anyway, we did it. It went out clean over the air, and it was the last time the SABC ever tried that kind of experiment (laughs).Footnote 52

Figure 6 Still images of Stockhausen's visit to South Africa from amateur critic Charles Weich's documentary video footage ‘Musici van heinde en ver’.

Embarrassingly enough for the organizers of the tour (who had evidently miscalculated Stockhausen's role in the post-1968 moment, or probably missed out on the sixties tout court),Footnote 53 the revolutionary potential of Stockhausen's did not escape ‘some radical young white students’ who ‘had apparently deliberately turned to Stockhausen with their [campaign for the equal rights of Blacks] because, as the innovator of music and as part of the Goethe Institute envoy, they expected him to be sympathetic to their cause’.Footnote 54 These are the words of Mary Bauermeister recalling Stockhausen's South African tour in her memoir of their life together. She continues, as Philip Miller discovered when the Goethe-Institut (which had also sponsored Stockhausen's 1971 trip) commissioned him to trawl through the composer's archives to trace its relation to Africa and to compose an artistic response,Footnote 55 with the astounding observation that Stockhausen had met, at the conclusion of his tour, with Steve Biko in Soweto:

To bolster their case, they invited us to visit Soweto, the amalgamation of black townships in southwest Johannesburg. There we were accompanied by Steve Biko and his black friends, who helped justify our entry into this territory. As whites we were not exactly welcome there. But as I had experienced in Harlem in 1964, the blacks saw in us the distantiated European; that is, the European who did not belong to the oppressors who ruled the land, so an understanding was possible – a mutual sympathy – without words, only by eye contact.Footnote 56

Although in his artistic response (the sound installation BikoHausen that imagines a dialogue between the two figures), Miller painted Biko and Stockhausen as two very different kinds of radicalsFootnote 57 – a view confirmed by William Fourie in homing in on Stockhausen as a ‘high modernist’ figure – what both authors underplay is that the meeting between Stockhausen and Biko came about through a group of white radical students. This is no insignificant fact. Indeed, as Ballantine's experiences at Cambridge and Stockhausen's reception in South Africa suggest, in the late 1960s and early 1970s Stockhausen functioned as high-art cypher for the New Left countercultural revolution. And, understood as an encounter mediated by the New Left, the coincidence of experimentalism and Black Consciousness becomes less improbable. When taking into account the convergence of Black Consciousness and New Left ideas in the work of Rick Turner (and many other South African thinkers, as Ian Macqueen has shownFootnote 58), what Biko and Stockhausen respectively stood for in 1970s South Africa, would not have been considered historically, politically, or philosophically (as Fourie argues) ‘incommensurable’ with each other.Footnote 59 At least from the limited white liberal perspective of the time.

Black consciousness is a rejection of the idea that the ideal for human kind is ‘to be like the whites’. This should lead to the recognition that it is also bad for whites ‘to be like the whites’. That is, the whites themselves are oppressed in South Africa. In an important sense both whites and blacks are oppressed, though in different ways, by a social system which perpetuates itself by creating white lords and black slaves, and no full human beings.

Rick Turner, ‘Black Consciousness and White Liberals’ (1969)From a Black Consciousness perspective, though, there was a more direct link between South African musical experimentalism and the radical energy of 1968 – a link that predated Ballantine's institutional interventions in Durban and was forged mostly outside the borders of South Africa, and of the ‘high art’ avant-garde.

In May 1968, a South African experimental jazz group, the Blue Notes – then exiled in London – released their debut album Very Urgent with Polydor in Britain.Footnote 60 Featuring Johnny Dyani on double bass, Mongezi Feza on pocket trumpet, Chris McGregor on piano, Louis Moholo on drums, and Dudu Pukwana on alto saxophone, the album was immediately understood ‘as an important statement of the British jazz avant-garde movement’.Footnote 61 The immense impact of the album on Britain's 1968, as Lindelwa Dalamba explains, can be inferred from a 1993 commemorative retrospective on 1968 in The Wire and a ‘Great lost recordings’ feature where Barry Witherden recalled ‘the flavor of ’68 in the shape of Very Urgent’.Footnote 62

The Blue Notes had arrived in London in 1965, after apartheid restrictions and legislation in South Africa made it increasingly impossible for the interracial group to perform and travel freely. Observing that by 1968 most South African popular and jazz musicians of any acclaim had left South Africa as exiles, Carol Muller has noted ‘that South African jazz creatively improvised in the South African exodus constituted a parallel discourse of personal and collective freedom to the explicitly political agendas of 1960s political movements in Europe, the US and South Africa’.Footnote 63 This also applies to the Blue Notes, especially after the release of Very Urgent (an eruption ‘in four extended tracks of free jazz’Footnote 64) that was seen to align the agendas of Western anti-institutionality with Black emancipatory ideals in ways that were ‘creative, liberatory and inspirational’, proving to be ‘a vital source of energy and innovation’ in the British jazz scene.Footnote 65

But the implications of viewing exilic South African jazz as part of South Africa's 1968 are broader still: if apartheid legislation effectively deferred South Africa's 1968 to the Durban moment of the early 1970s, when global ideas on educational and social reform were filtered back into university and public discourses by figures such as Turner returning from abroad, apartheid also displaced and dispersed that energy geographically by forcing locally borne radicalism into an exilic consciousness, thereby severing South African forms of experimentalism and radicalism from the local institutions and discourses that could benefit most from their transformative agendas. Apartheid was a political system. But it also engendered dispersed, insular, and necessarily myopic bubbles of analogous ideas and practices. Even when these were radical.

Ballantine would not meet a member of the Blue Notes until 1986, when – in an explicit political refocusing of his research agenda to the ‘local’ – he interviewed Chris McGregor in London as part of his jazz research of the early 1980s that culminated in the monograph Marabi Nights (1993). During his time at Cambridge, though, Ballantine was unaware of the Blue Notes, which is as revealing of his own political consciousness at the time, as that of the music department in which he studied. Despite their acclaim in London's jazz scene of the late 1960s, their brand of musical experimentalism and avant-gardism drawing explicitly on South African musical vernaculars and thereby connecting the South African political situation to the emancipatory ideals of 1968, did not intersect with the version of 1968 that powered the Cambridge student arts initiatives in which he participated or, later, the work of the Durban New Music Group – initiatives all firmly rooted in Euro-American experimental and avant-garde aesthetics.Footnote 66

It is the absence of the Blue Notes, then, that is significant in understanding avant-gardism at South African universities during the 1970s and early 1980s. Their absence is all the more striking, because, before settling in Britain in 1965, they were not unknown in radical university music circles in South Africa, although mostly in an ‘extracurricular’ way. After the collapse of bohemian interracial Cape Town jazz scene of the 1950s,Footnote 67 and the forced closure of interracial jazz venues around the country after 1963, it was the white liberal universities, so Lindelwa Dalamba argues, that harboured what she calls the ‘jazz art world’ in South Africa: ‘not all post-Sharpeville jazz was of the townships; an important institution, which was mostly unwilling to take on this role but was urged by its few radical members to do so, emerged as jazz's temporary space: the “liberal” university’.Footnote 68

Although jazz would not formally be taught at South African universities until the 1980s (when Ballantine recruited Darius Brubeck and his South African wife, Cathy, from the United States to start a jazz programme at the University of Natal in 1983 – the first such programme in South AfricaFootnote 69), many white jazz artists (such as McGregor) were enrolled for conventional Western art music degrees and connected with their Black jazz peers through what was, for reasons of political rather than educational expediency, defined by white radical students as ‘community outreach’ initiatives. This is indeed how McGregor first joined a jazz ensemble in Cape Town.Footnote 70 The Blue Notes also toured the so-called ‘liberal’ universities in the 1960s, performing at the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Cape Town, and the historic Black University of Fort Hare. Notably, they performed at least twice (in 1963 and 1964) at the University of Natal as part of the university's arts festival (Figure 7).Footnote 71

Figure 7 The Blue Notes performing at the then University of Natal Pietermaritzburg's Great Hall in 1964: one of the band's last performances in South Africa before its members went into exile. Photograph courtesy of Norman Owen-Smith.

It would take another twenty years for Ballantine to re-integrate jazz into university life. That this re-integration should have been induced by the expansionary thought brought about by a Western-style avant-gardism that took its orientation from a European aesthetic impasse in a colonial context where technologically driven ‘progress’ could easily morph into ‘neo-frontierism’, speaks to the limits of possibility for radical projects in white public spaces in universities at the time; an epistemic deficit, no less, oftentimes violently induced and insidiously nurtured by the apartheid government's cultural tribalization and isolationism. A resistance aesthetics marked by suppression and terror, which unravelled only slowly and, in many ways, still persists.

White liberals remain whites first and liberals second. They are offended by the barbarities of South African society but not sufficiently outraged to be willing to risk sacrificing their own privileged positions.

Rick Turner, The Eye of the Needle (1972)Re-enter the ARP-2500 modular synthesizer. Acquired for the Department of Music at the University of Natal in 1974, the machine stood for an idea: the avant-garde, and, by extension, the Euro-American intellectual ferment that powered vanguardism as a liberatory politics at a liberal South African music department in the 1970s. The ring-modulators, contact mics, delay lines, and DIY electronics of the New Music Group stood for another: anti-institutional experimentalism. Concluding ‘Towards an Aesthetic of Experimental Music’, Ballantine discusses Benjamin's view of art as ‘the creation of a demand that could be fully satisfied only later’. This was, according to Ballantine, the same dialectic present in the difference between the ‘avant-garde’ and the ‘experimental’:

This dialectic precisely defines the relationship between experimental and avant-garde music: not a fruitless opposition but a fertile and changing interplay between the more and the less radical, the more and the less systematized. The two are complementary – indeed, possibly of necessity; one might ask whether either could exist in its familiar form without the other. And this connection points to their relationship to the modern world: they are the twin parts of what we might designate a quasi-scientific practice. In other words, the one experiments, the other adopts; the latter has implications (‘hypotheses’) which the former explores (subjects to experiment).Footnote 72

But, noted Ballantine, avant-garde music ‘also provides aspects for experimental music to contradict’. Whereas music of the avant-garde was mostly ‘still exclusive in its skill orientation, still elitist’, experimental music was ‘inclusive and participatory’. Employing the language of, and directly referencing British counterculture as an example of the latter, Ballantine noted that the difference manifested also in the ‘different social status of the two musics’:

Boulez is performed at the Royal Festival Hall, Cardew in Ealing Town Hall; journals devoted to the avant-garde (e.g., Perspectives of New Music) are academic in a conventional sense, those devoted to experimental music (e.g., Source) are iconoclastic and may even be antiacademic in tendency; avant-garde composers tend to be respected ‘establishment’ figures, while experimental composers are, if anything, members of the ‘antiestablishment’.Footnote 73

And herein lay for Ballantine the ‘remarkable significance’ of Stockhausen. Stockhausen existed, as Ballantine's illustrated diagrammatically, ‘at the point where the dialectic between experimental and avant-garde music becomes manifest’ (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Ballantine's diagram to illustrate the ‘remarkable significance’ of Stockhausen.

Although Ballantine never mentions apartheid or the South African political context in his essay on experimentalism, given his involvement in anti-institutions as a student and the impact of 1968 on his thinking, one can surmise that this symbiotic relationship between the avant-garde and experimentalism may very well have applied to the problems of institution-building in apartheid South Africa that he faced and resolved through radical musical, curricular, and organizational experiment. As such, avant-gardism at the music department in Durban not only encompassed improvisation and the performance of avant-garde and experimental works in the Western tradition, but also eventually extended to the gradual orientation of the institution towards the local and to an emancipatory politics of music, realized under Ballantine directorship in a series of departmental ‘firsts’:

We were considered to be out on a limb [because] of things that we were doing here: introducing a degree in ethnomusicology; appointing the first black lecturer in a South African music department; introducing jazz.

[W]e needed to start taking seriously the local cultures. We had to wisen up to where we were [and] that wisening up was part of the greater political shift that was to take place. That for me was very conscious. I couldn't have felt that I should be here if I didn't have the sense that I was at least trying, in those ways, to make that political engagement. I was trying to make it all the way through from my research and writing, through to the way the Department of Music was being structured, the staff we were appointing, to kinds of courses we were designing, to my own teaching, and, beyond that, to entrance criteria, and so on. To try and think about this in a new way: as an anti-apartheid enterprise.Footnote 74

Ballantine's programme played a decisive role in conscientizing the department's white students to the political situation in South Africa and the possibilities of Marxist-inspired music scholarship.Footnote 75 Carol-Ann Muller, for example, has written about how ‘the progressive thinking’ of the group of musicologists at the University Natal in the 1980s shaped her interest in South African jazz history: ‘Ethnomusicologist Veit Erlmann conducted pioneering work in Black South Africa music history … Kevin Volans was experimenting compositionally with African musical material,Footnote 76 Darius Brubeck established the Centre for Jazz an Popular Music Studies, and Ballantine was teaching upper-level undergraduate seminars on South African and American Jazz.’Footnote 77 It was in these seminars that she first heard about musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Kippie Moketsie, Johnny Dyani, and Dollar Brand. ‘Learning about them bordered on illegal action’, she notes, since many of these musicians were officially banned in South Africa at the time.

Nevertheless, the music programmes of the 1980s at the University of Natal necessarily formed part of a ‘resistive enactment of the apartheid script’,Footnote 78 as Nishlyn Ramanna – another former student of Ballantine's – has pointed out. While for ‘some members of the university community … jazz's presence on campus constituted a utopian prefiguring of a post-racial future’, for some of the department's first Black students, ‘jazz's marginal position in the curriculum replicated apartheid hierarchies and inequalities’.Footnote 79 Muller recalls how, although the music library was stocked with an impressive collection of jazz recordings, one of the key messages of the jazz seminar was that Black jazz musicians in exile ‘would not be willing to talk to White South African researchers’ – an assumption she later found to be untrue when she successfully contacted and interviewed Abdullah Ibrahim and Sathima Bea Benjamin in New York.Footnote 80 Despite their progressive agendas, Ramanna notes, the occluding operations of whiteness would have prevented ‘the almost exclusively white staff of the music department [to] have foreseen [these contradictions]’.Footnote 81 Ballantine's work in the university was therefore ‘constrained by the larger racial politics of the country, and inadvertently replicated it in certain respects’.Footnote 82 This is in line with Premesh Lalu's argument that ‘[c]laiming an Enlightenment inheritance arguably left the [South African] liberal English university blinded to its role in the formation of racialised subjects’ and that the ‘notions of academic freedom and university autonomy that were at the core of the liberal university proved ineffective in realising the critical potential that gave rise to the university in the first place’.Footnote 83 The extent to which the global deployment of modernism in the Euro-American avant-garde and experimental traditions served a similar role in university and public discourses – inside and outside of South Africa, and also via the British institutions that nourished the idea of the liberal university in colonised parts of the globe – remains to be investigated.

During the ‘Durban moment’, before such time that the aesthetico-political ‘demand’ created by apartheid could be realized in actual political restitution and material institutional, curricular and societal change, Ballantine – straddling the liberal and the radical positions Turner described and critiqued – chose neither an overt politics of dissent, nor to relinquish the academic project, or to buy into the state-sponsored second-tier mimic-avant-gardism of the SABC or his musicological and compositional peers at Afrikaans universities in South Africa. Instead, he operationalized a ‘Stockhausenesque’ organizational model for musical innovation and experimentalism within the repressive – and dangerous – South African university context of the 1970s: ‘Being as radical as possible, without being shut down.’Footnote 84

* * *

Ballantine is L. G. Joel Professor Emeritus, and University Fellow, of what is now the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Under his directorship, the Music Department of the University of Natal was the first music department in South Africa to include courses on Indian music and African music and dance in the mainstream curriculum, the first to offer specializations in Ethnomusicology, Jazz, Popular Music Studies and Music Technology, and the first to appoint a Black staff member.

* * *

Süsse was appointed professor of music at the State University of Music and the Performing Arts in Stuttgart in 1980 and directed their electronic music studio from 1998 to 2002. He retired to Durban in 2005, then moved to Cape Town in 2012.

* * *

The electronic music studio in Durban was named after Süsse's successor, Gerald La Pierre, who died tragically in a motorcycle accident in 1981. Kevin Volans directed the studio from 1981 to 1985 and Jürgen Bräuninger, a former student of Süsse's in Stuttgart, from 1985 until his death in 2019.

* * *

Biko died on 12 September 1977 from a massive brain haemorrhage, after being detained and brutally interrogated by police.

* * *

Turner was assassinated in front of his 9-year-old daughter at his home at 32 Dalton Avenue, Durban, on 8 January 1978, allegedly by the South African security forces.

* * *

In a deal brokered by Jürgen Bräuninger in the 1990s, the ARP-2500 was sold for a very respectable price to a buyer in New York City.