Introduction

The adoption of theories derived from the ontological turn, new materialism, perspectivism and posthumanism have affected many strands in archaeology and in its most successful appearances has offered fundamental critiques on western essentialist categories as well as opening up new avenues in research: on landscapes, Indigenous theory, objects, on the body and personhood and on a diverse quantity of societal issues in past and present (Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Conneller Reference Conneller2004; Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Harris Reference Harris2021; Harris & Robb Reference Harris and Robb2012; Harrison-Buck & Hendon Reference Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; among many others). The theories have different historical and political contexts and know a few nuances, but all approaches seek a better repositioning of the human among other non-human actants, questioning the ‘human’ as a predominantly male western subject, and advocating critical materialist attention to the global, distributed influences of late capitalism and climate change (Alaimo & Hekman Reference Alaimo and Hekman2008; Haraway Reference Haraway1990). They thereby argue that worlds can be ontologically different and are not just a matter of perspective (epistemology). As a result of this, scholars increasingly allow more radical, other ways of knowing and being into the academic discourse. In this paper, I will umbrella the approaches as ‘new materialism(s)’. The diverse nature of new materialist and posthuman approaches, especially in the context of critical Indigenous, decolonial, feminist and anti-racial theory, has huge potential, and in Roman archaeology they are gaining in interest (see Selsvold & Webb Reference Selsvold and Webb2020). However, not much serious integration has occurred yet, occasionally resulting in an impoverished understanding of what new materialism is among some strands in (Roman) archaeology. Recently, Roman scholars have voiced criticism of the apparent flat ontology and the new form of object fetishism that new materialism would bring and especially have criticized the inability to account for human inequality and the ‘darker aspects of Roman history’ (Díaz de Liaño & Fernández-Götz Reference Díaz de Liaño and Fernández-Götz2021; Fernandez-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Maschek and Roymans2020, 1630–31). Although such criticisms are in part justified when it comes to how some fields in archaeology have interacted with more object ontology-focused approaches, through this narrow understanding they fail to consider the full scope that new materialism brings to exactly those parts of marginalized histories.

In this article therefore I wish to bring a constructive intervention by showing how Roman archaeology can be aided by approaches derived from new materialism frameworks. Approaches that have integrated posthumanism with race, colonialism and queerness (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; Chen Reference Chen2012; Ellis Reference Ellis2018), and the works that have advocated for such perspectives in archaeology (Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Marshall Reference Marshall and Thomas2020; Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021) are especially valuable to the study of the Roman past. Postcolonial efforts of the past decades have pointed to the subaltern and marginal existence in the Roman past, but new materialisms are able to create room for more radical and fundamental ways of otherness. Through the use of new materialisms this paper can hopefully prove to do two things: first, form a new way to counter the false western cultural intimacy we still uphold with the Roman past, thereby adding to previous post-colonial efforts to decolonize Roman archaeology. Secondly, show, in a way not done before, the ontological fluidity that existed in the Roman world and the essential alterity in being that was present. This ontological fluidity presents itself through the so-called ‘speaking’ objects (objects with inscriptions in the first person) and through objects that were actually spirits in Roman religion, but also through the enslaved Romans that were considered ‘speaking tools’ rather than humans (Varro, Res Rusticae 1.17): these are instances showing posthuman alterity crossing lines between matter, spirit,and human not symbolically, but ontologically. To the modern mind, the first objects are counterintuitive and the second are immoral. However, the (elite) Romans managed to work happily with both these concepts at once, which is telling us something profound about the Roman faculty for ontological fluidity, and the consequences for those people and things that bore the brunt of it. In the coming sections I will first discuss new materialism and its potential value for Roman archaeology, and then move to how posthuman radical alterity forms a new way to regard the Roman past.

Romans Otherwise: a false cultural intimacy

Criticism put forward by archaeologists against new materialism occurs mostly when it becomes conflated with symmetrical archaeology and object-oriented ontology and through that lens deemed problematic, as the flat ontology (in which humans and things exist in the same state of being as any other object) is considered a-human, suppressing lived experience and whitewashing history (Gardner Reference Gardner2021; Ion Reference Ion2018, 191–203; van Dyke Reference van Dyke2021). I am in full agreement with this critique, but this is not new materialism or posthumanism. Critical posthumanism does not stop studying humans (Cipolla Reference Cipolla2021), nor is it oblivious to social inequalities and asymmetries (Harris Reference Harris2021). The fact, however, that it is the object-oriented ontology and material turn variant of object agency that became popular in archaeology, and perhaps disproportionally defended in the field, is remarkable. This might have to do with the still often peripheral positions that post-colonial and feminist theory take in the wider archaeological debate, but perhaps even more so with the affordances that object-oriented ontology brought as a theory that profoundly sidelines the human in favour of things. Things, and with them the discipline of archaeology, suddenly mattered within broader philosophical debates, and this led to a neglect of the more ethically informed new materialism approaches as well as archaeology's general narrow view on what the posthuman critique entails.

New materialisms are a radical rethinking of the human position. They emerged from the post-colonial critique of the failure seriously to integrate Indigenous voices and philosophies in scholarly debates (the ontological turn: Holbraad & Pedersen Reference Holbraad and Pedersen2017) and advocated for the recognition of local Indigenous theories as equally real and valid as the ones derived from western ontologies (Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021, 55). What is needed, their advocates claim, is more ‘epistemic disobedience’, a break from the hegemony of Eurocentric discourse and the creation of a shared field of western and non-western knowledge (Mignolo Reference Mignolo2009, 173–4). One of the ontological turn's most prominent protagonists, Viveiros de Castro, convincingly showed with his framework of perspectivism that there is more than just ‘cultural difference’ or ‘epistemology’, but that being in the world can indeed be different (Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998; Reference Viveiros de Castro2004; Reference Viveiros de Castro2012). This counts for the relationships between human and non-human bodies and material things, and for the understanding of the body itself (Harris & Robb Reference Harris and Robb2012) This more radical acknowledgement of the rethinking of nature and being is why it is considered the next step in the post-colonial debate, and so far it has opened up different and exciting new avenues of research in archaeology and anthropology on the global south and led to a broader acceptance of scholarship already doing this (among many, see for instance the works of Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Gillett Reference Gillett2009; Hountondji Reference Hountondji2002; Laluk Reference Laluk2017; Nicolas Reference Nicolas2010; or Soares Reference Soares2021). It also enabled a further constructive critique of the hegemony of western philosophy, a philosophy which already used Indigenous knowledge, but often without much awareness, interest, or acknowledgment (Todd Reference Todd2016). In the context of Indigenous thought and colonialism it is important to note that ‘adopting’ perspectivism as a way to rethink western scholarship is hazardous. Using non-western or Indigenous philosophy to unsettle the western framework might be an interesting exercise in alterity for the white western scholar, but for many non-white, non-western and indigenous scholars it is not an intellectual tool, but part of a real, everyday struggle. Cherry-picking or extracting Indigenous knowledge just to ‘challenge western ontology’ is an act of appropriation of and capitalization on Indigenous thought, a neo-colonial strategy of abstraction that should be avoided (see also Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021, 74–9; Marín-Aguilera Reference Marín-Aguilera2021).

Further, a risk lies in the denouncing of human exceptionalism in new materialist thinking in that it might assume a rather simplistic binary between Homo sapiens and non-Homo sapiens (Ellis Reference Ellis2018, 136; also Khatchadourian's Reference Khatchadourian2020 response to Fernandez-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Maschek and Roymans2020). This binary fails to acknowledge human inequality, and the posthumanist emphasis on human animality and objecthood obviously also sets off alarm bells for those who are still struggling to be recognised as fully human (Ellis Reference Ellis2018, 139). This challenge has increasingly been picked up by scholars who integrate social justice theory in posthumanist research (Ellis Reference Ellis2018; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2015; Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014). I believe this is the way forward for archaeology. If we critically integrate posthumanist and new materialist works in (Roman) archaeology derived from feminist, anti-racist and Indigenous scholarship more broadly (see Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021), we can shift from a turn to things, to a critical reassessment of unequal relationships in the past. For Roman archaeology this means that the research does not build off work on materiality or object ontology, but rather from the existing body of post-colonial Roman scholarship (Bénabou Reference Bénabou1976; Gardner Reference Gardner2013; Jiménez Díez Reference Jiménez Díez2008; Mattingly Reference Mattingly2011; Van Dommelen Reference Van Dommelen2011; Reference Van Dommelen2019; Webster Reference Webster2001, 209–45) of which I see critical posthumanism as a next step. Why it can be considered a next step I will explain below.

Not disregarding human inequality and not appropriating Indigenous theory, but using posthuman and new materialist thought to advance the decolonization of classical antiquity and show otherness without essentialism, is incredibly important for the Roman past. Decolonization involves thinking differently; ‘thinking at the border’, as Mignolo writes (Reference Mignolo2000, 161). In this respect, ‘classical’ (Greek and) Roman antiquity still deals with a problem, not of exoticizing, but of an uncritical implicit appropriation of a (western) self and although addressed, the dominant narratives about the ‘Classical’ past have not been sufficiently deconstructed. The importance of further deconstructing the basis of ‘western’ thought for the classical world through posthumanism, perspectivism and more fundamental ways of alterity therefore cannot be overstated, for the simple fact that the study of the Greco-Roman past is still very often subjected to implicit western rationalist prejudices and reviewed within binary categories as if they were similar in the past. Due to the intermittent adoption of aspects of Greco-Roman culture into western European history (from language, aesthetics to law), the relation of the West to the ancient Greek and Roman worlds suffers from what Herzfeld deems a false ‘cultural intimacy’ (Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld2005, 1–38). This has been really damaging to certain subfields like, for instance, the study of Roman religion, where a strict divide between human, object and spirit did not always exist (Mol Reference Mol2019, 64–81). Of course, post-colonial criticism as well as many subfields within provincial Roman archaeology have advocated convincingly for the recognition of otherness in the Roman past. However, even these have not fully opened the existing blind eye that some scholarship retains towards such aspects of alterity. For this reason, we need something more radical that works from a basic acceptance that the Romans inhabited worlds that were fundamentally different, where the whole concept of being was different. Below, I will present two interrelated instances that show the existence of ontological fluidity in the Roman world.

Ontological fluidity and radical alterity in the Roman world

Through the ontological turn, animism recently received renewed attention in anthropology as a way of deconstructing binary ontologies and essentialisms in non-western religion. A first and very clear presence of animistic practices enfolds itself through a very common phenomenon we see appearing already in the Archaic Greek period, and which is employed throughout the Roman past: the so-called ‘speaking objects’ (Burzachechi Reference Burzachechi1962; Carraro Reference Carraro, Lomas, Whitehouse and Wilkins2007; Whitley Reference Whitley and Nevett2017). These are objects engraved with a first-person inscription: from the famous Phrasikleia Kore, the Nestor Cup, Mantiklos Apollo, or Francois vase, to the boundary stones in Athens (‘I am the boundary of the Agora’) and countless other votives, vessels and statues from the Greek, Etruscan and Roman world; they all speak to us directly (Fig. 1). For the Greek past, a recent hypothesis posed by Whitley even goes so far as to state that the Greek alphabet was not adopted to write down Homer, or transcribe human speech, but rather to allow an object to ‘speak for itself’ and extend personhood by changing the relationship with gods and men through things (Whitley Reference Whitley and Nevett2017, 73). Archaic Greece can, of course, in no way be conflated with Rome, but the way in which objects continue to speak in the Roman period show that this ontological fluidity between objects and persons also exists here. Speaking objects are a very common occurrence and attested widely on domestic pottery and oil lamps throughout the Roman world (Agostiniani Reference Agostiniani1982; Vavassori Reference Vavassori2012, 95–9, studying speaking objects in Gaul, Spain and Italy). In Pompeii there are several, such as a dish saying ‘give me back’ (redde me) or a vessel saying ‘I belong to Epaphroditus, do not touch me’ (Epaphroditi sum tangere me noli) (Fiorelli Reference Fiorelli1861, 417, 461). They also appear in in funerary contexts such as in Figure 1, where the object seems to speak on behalf of the deceased. Speaking objects in Roman scholarship have predominantly been studied as a domain of Latin epigraphy, its material dimensions often ignored. What is important, however, is that rather than to put this away as a habit of writing or invocation, we should see such practices as a testimony of the reality of a different nature, a nature in which objects could indeed sometimes be animate and speak for themselves.

Figure 1. ‘Don't touch me! I'm not yours; I belong to Marcus’ (ne atigas non sum tua marci sum; CIL 1(2).499; 15.6902). Oil lamp from the Esquiline necropolis in Rome, mid Republican (mid third–end second century bc). (Musei Capitolini/Museo della Civiltà Romana AC 8243. From the 2023 exhibition La Roma della Repubblica. Il racconto dell'Archeologia [Rome in the Republican Period. The archaeological story].)

This different nature is also observable in objects that do not speak. Although animism is not a very widely studied subject within Greco-Roman religion, scholars who did examine it noted the commonness of objects being animate in various ways (Gordon Reference Gordon1979; Neer Reference Neer and Elsner2017; Platt Reference Platt2011). Richard Neer, for instance, observed animism through the statue of Aphrodite of Knidos, questioning whether she was a statue or a god, suggesting that the conflation between image and deity is non-representational and that competent beholders no longer needed to refer to an inner representation to see gods such as Aphrodite (Neer Reference Neer and Elsner2017, 22). This conflation, therefore, made the statue into a spirit: a difference in being rather than one in representation. The examples for the existence of a more fluid ontology blurring human and non-human in the Roman world manifest themselves continuously and become especially apparent in Roman religious practices. We can observe it in the practice of Damnatio memoriae (condemning the memory of a person by destroying their images), anatomical votives (as enchainment between human and divine such as the work of Graham Reference Graham, Graham and Draycott2017 showed), in the treatment of ancestor portraits, in inscriptions and graffiti; indeed, combining archaeological, epigraphical and textual sources provide wide-ranging evidence and a convincing context for the study of ontological difference and animacy. Stones could sometimes be alive in the Roman past in aniconic objects of worship in ritual contexts, as the ‘rock’ of the goddess Cybele, brought from Pessinus in Anatolia to Rome in 204 bc, testifies. It was widely present in iconic objects as well, where statues and even paintings did not seem to merely represent but seemed to be protective spirits. There are countless literary descriptions of spirits that somehow ‘exist’ or ‘inhabit’ natural landscape features or objects. Ovid describes a grove on the Aventine that has ‘a spirit within’ (Numen inest: Ovid, Fasti III, 296–7; see also Mol Reference Mol2019) and boundary marks in the form of stones or stumps possessing spirits (Ovid, Fasti II, 639–42). Rüpke's study on Propertius Carmen 4.2 tells us how a deity, the god Vertumnus, speaks about possessing a body and statues (Rüpke Reference Rüpke2016, 45–58; Propertius El. IV.2, 1–64). Propertius is interested in the variety of material beings of the god rather than in determining some normative ‘essence’ and the separation between god and statue (‘I was a maple stump. Marmurius, divine sculptor of my bronze form.’) becomes completely erased in the final verses. Rüpke suspects that this kind of ‘fetishist’ thinking is not a poetic exception, and the concise but wide dissemination of evidence just presented I think sustains this thought. Reviewing the overwhelming evidence, I believe that we can be more radical even; the idea that we should approach some (not all!) statues not as just material or representational, but as spirits, to me seems not only a refreshing and exciting, but also a more faithful way of understanding aspects of everyday Greco-Roman experience and material culture.

Arguing against the Victorian and exoticizing idea of animism that was ascribed to non-Christian communities (where animism was regarded a religious ‘mistake’), the new materialist wave of animism adopted animacy on the basis of a ‘shared concern with the potential for the personhood of nonhumans’ (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017, 293; see also Harvey Reference Harvey2017). Although the new definition is still based in opposition to (and therefore dependent on) a western norm, when not understood as universal but as metaphorical and local it can be very valuable (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017, 294, 306–7; Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009). The examples of the existence of animism shown above have wider consequences for how we should look to the Greco-Roman past, as it bears evidence of a particular configuration of distinctions between humans and non-humans that are irreducible to modern western distinctions (Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998, 469–88). While incorporating ontological fluidity and animacy in the study of Greco-Roman religion is not new, it never received much serious attention, but there is also general lack of understanding. This issue was observed by Hunt in her work on sacred trees in Roman religion, where she noted that it was the post-enlightenment tendency to rationalize Roman culture that had a very restricting effect on the understanding of Roman religion (Hunt Reference Hunt2016). An even more poignant example of how this false cultural intimacy has affected Roman studies comes from Richard Gordon, who pointed out that the western ways of translating ancient sources have systematically obscured the Greco-Roman view of divine images and their relations (Gordon Reference Gordon1979, 5–34). All such practices have clearly shrouded the existence of animism as a continuing ontological aspect of Roman religion, which, even when it was used, was mainly regarded in an evolutionary perspective in which animism was the less developed stage progressing towards a more sophisticated (anthropomorphic) way of worship. In reality, as I have tried to demonstrate, the boundaries continued to be fluid and the Romans inhabited a world in which the notion of being could occasionally be radically different from modern western society. This opens up a wider framework of investigation, which can provide a more diverse view on aspects of the Roman past. A subject in which such a wider framework is especially helpful is that of Roman slavery.

Roman slavery: parahuman entanglements

Slavery and speaking objects are not two different cases: they exist within this ontological fluidity and are one side of the same coin; the entanglements between objects and personhood, however, take different shapes. Critical perspectives inspired by posthumanism and new materialism, notably those of Allewaert on colonialism and parahumanity and Ellis’ work on slavery and posthumanism (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; Ellis Reference Ellis2018), can help us better understand this particular entanglement, adding to the ongoing debates on comparative, anti-colonial and materiality approaches to Roman slavery by scholars like Bodel (Reference Bodel, Bradley and Cartledge2011; Reference Bodel2019); Joshel & Hackworth Petersen (Reference Joshel and Hackworth Petersen2014); Lenski (Reference Lenski, Lenski and Cameron2018); Trimble (Reference Trimble2016); or Webster (Reference Webster2005; Reference Webster2008; Reference Webster and Eckhardt2010). The new materialist interrogation in this case is not only considered a helpful step for rethinking Roman slavery, but will reinforce their efforts and might open new, different sets of questions and avenues.

Ontological alterity does not only apply to spirit-objects but also to those social—immoral—contexts reflective of Roman colonial power inequalities and exploitative strategies (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2008, whose work has been key in highlighting the darker sides of empire in the field of Roman archaeology; see also Mattingly Reference Mattingly2011). Slavery, in all its diversity and complexity, was a crucial building block of Roman imperialism, a structurally integrated element in Roman institutions, economy and consciousness too, where mass-scale enslaving was seen as a ‘pragmatic recipe for growth and consolidation of conquests’ (Garnsey Reference Garnsey1996, 7; Bodel Reference Bodel, Bradley and Cartledge2011). How the slave existed, ontologically speaking, we can only fragmentarily delineate from written and material sources, but these prove to be vital informants: in these accounts the enslaved were conceived as kinless, stripped of their old social identity when not born into slavery, and even though they had a legal position as human beings, and certain moral rights, they were also conceived of as property. From one of the most famous pieces of written data, Aristotle's natural slave theory (Aristotle, Politics 1254b, 16–21), we learn they were seen as ‘living tools’, ‘not belonging to himself but to another person’, and as ‘property used to assist activity’. In three steps, therefore, Aristotle turns the slave from human to non-human, (although Agamben argues that such tool-being of the slave's body should be conceived more as a substantiation of the master's body, like a bed or clothing: Agamben Reference Agamben and Kotsko2016, 12). The Roman first-century bc author Varro did not even place the enslaved within human categories, but among agricultural instruments (Varro, Res Rusticae 1.17). The slave represented the articulate instruments (instrumentum vocale), the tool with a voice among the inarticulate (cattle) and the mute tools (vehicles; although recently criticized by Lewis Reference Lewis2013). These accounts might be considered wordplay, and not representative for the whole Roman population; however, slaves under Roman law were literally objects, treated under the Law of Things as res mancipi: land, buildings, rights (servitudes), slaves and farm animals, whose ownership could only be transferred by legal ritual (Bradley Reference Bradley2000; Joshel Reference Joshel1992, 28–37; on the ambivalence of slaves as things or persons in Roman law, see Pelloso Reference Pelloso2018). Sandra Joshel, who analysed the slave in Roman literature, further notes them to be conceived as a ‘fungible thing’ throughout the sources; the slave was exchangeable, replaceable, substitutable and could be turned to any use: an item for sale, the repayment or collateral for a loan, a gift, an inheritance, or an item to be mortgaged (Joshel Reference Joshel, Bradley and Cartledge2011, 215; on fungibility, see also King Reference King2016). The literary sources consistently point out that slaves, though they were not like animals, were also not like humans either (Garnsey Reference Garnsey1996, 25). Outside the literary record we see such a non-human personhood confirmed, through epigraphic sources as well as archaeology.

Webster noted that Roman scholarship is notoriously reticent when it comes to a comparative approach of slavery studies; however, her work (2008) convincingly showed how a diachronic comparison between different contexts of historical slavery can lead to new paths and interpretations. Recent social justice, Indigenous and antiracist posthuman critiques such as those of Ellis, Allewaert and others (Chen Reference Chen2012; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014) have reshaped the debate significantly and I believe these works can form a serious contribution to the existing study of Roman slavery; especially the work of Monique Allewaert on plantations, personhood, and colonialism in the American tropics aids in opening up the discussion on Roman slavery. Allewaert draws from new materialist work to create different understandings of enslaved bodies and agency and the organic and inorganic parts that compose beings and places (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013, 18). She uses the term parahuman to describe the African American enslaved in tropical plantation zones and creole contexts, who were described as neither human nor animal. Apart from descriptions however, Allewaert argues that Afro-Americans’ own oral stories and mythology on animality and objects, that all show particular and close interrelations with other non-human forces, affirm a non-/parahuman status. Through different embodied realities, the enslaved suspended their less-than-human-legal status, and their model of personhood was also parahuman out of a deep scepticism about the desirability of the category of the (colonial) human (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013, 86). Parahumanity therefore is more than just subjugation but also testifies of different modes of self, criticizing the category of the human that was unevenly available to the enslaved (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013, 22). Whatever name we give it, parahuman, or non-human, it exists as a category that lies beyond the boundaries of what is considered ‘human’ in a given historical context. Through different interactions with the material, animal and spiritual world, ascribed as well as embodied, and as a form of resistance, this alterity emerges and creates different personhoods. It is this ontological status of the enslaved as a different non-human category that I believe is worth tracing for a Roman context.

The parahuman in Allewaert's work stretches the dominant Enlightenment tendency to pose the human as the apotheosis of natural historical and cultural processes, but within this the para-/non-human is not just dehumanizing, but also a powerful and resistant category. We need to be more speculative with the Roman enslaved of course, as we do not have their oral stories: they were a different and a more diverse group ethnically than the trans-Atlantic enslaved. Although it has been argued that Roman slavery was different because of the possibility of manumission (the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers), and therefore a temporary and processual status rather than a fixed one (Bodel Reference Bodel, Bodel and Scheidel2017, 89–91), manumission was very selective (Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2011, 140) and in no way could have affected the lived everyday experience of being unfree. Not all the Roman enslaved were treated badly; some are known to have had personal possessions and acquired reasonable positions in society, but there exists widespread evidence for degrading work in horrifying conditions, torture and structural sexual abuse which we cannot ignore. It is highly problematic to use exceptions as an argument against paying attention to a concept like parahumanity, as we would exclude what was probably a large group of Roman enslaved who existed not just in poor circumstances, but existed differently altogether, and who go largely unaccounted for in the historical record. Like the emergence of creole enslaved identities, the non-human moves beyond a matter of Roman elite perception; being enslaved profoundly affected the world and being of a person, producing a reality and affecting the slave's sense of personhood. It is here that I see the necessity of new materialism: by interrogating the interrelations between objects, humans and non-humans it is possible to bring a different understanding to Roman slavery beyond the archaeological approach of looking for visible traces of slavery in material culture.

Material alterity

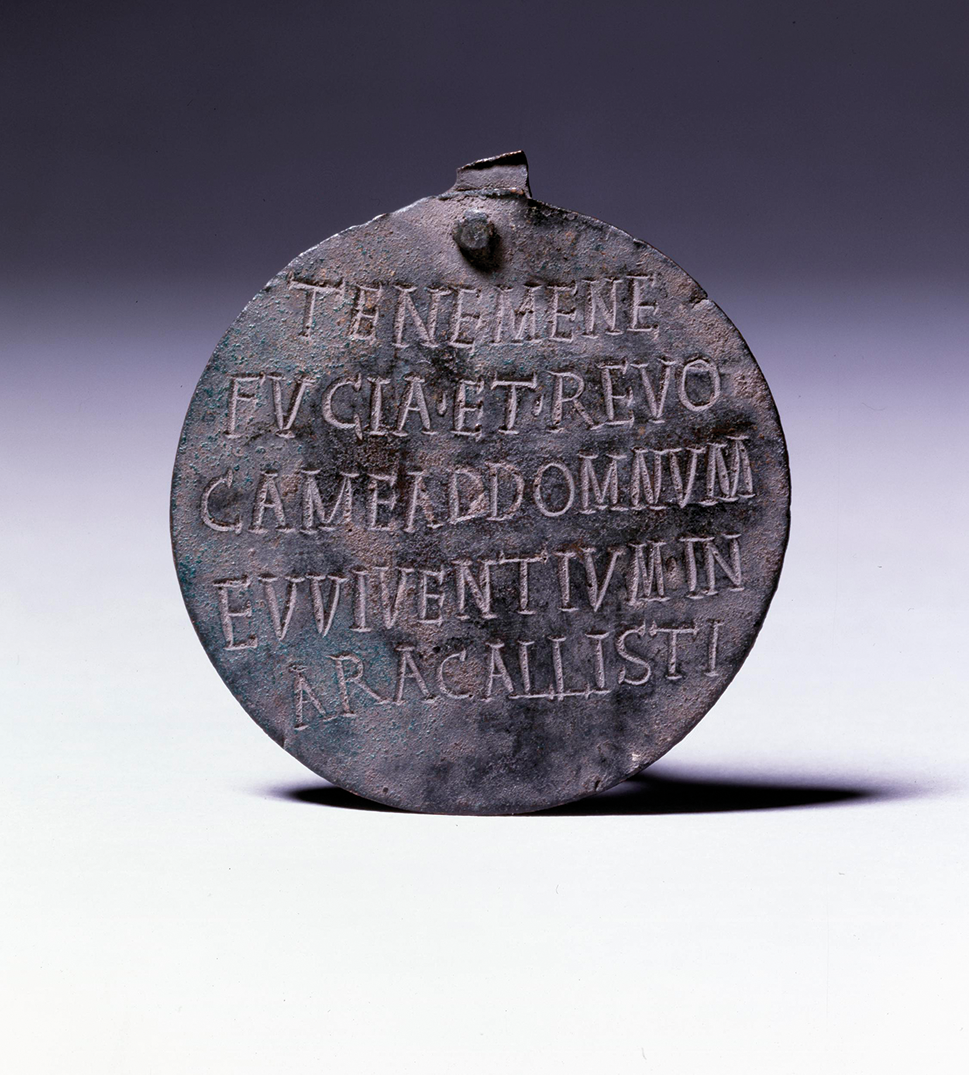

When we look at material culture that can be connected to Roman slaves (the few traces we possess which are linked to their own lived experience) and examine the way they were seen and treated by owners and other non-enslaved people through literary and material evidence, as well as the way we see them being represented in art, we can understand how the parahuman or posthuman can be useful in thinking about slave-personhood. First, also to show the relation in ontological fluidity between this section and the above, we move to another speaking object: an inscribed slave collar (Fig. 2) with the text ‘hold me lest I flee, and return me to my master’. Such collars—about 40 of them are attested throughout the Empire—probably functioned as embodied reminders of enslavement, a punishment for runaways, or a more astute means by the owner to mark a runaway slave rather than using a permanent tattoo (as a slave who attempted to escape was worth less on the market and a collar would only be a temporary mark, although they have been found in graves, proving they could be less temporary than assumed: see Trimble Reference Trimble2016, 461–2. For more on marks and Roman enslaved, see Kamen Reference Kamen2010). As Trimble showed in her study of the Zoninus collar, what the collars do in terms of their shape and inscription is to entangle an object with the ownership and control of human bodies (Trimble Reference Trimble2016). The neck collar as an object generally became associated with slavery, but not just as marking domination; with their connection to runaway slaves, Thompson (Reference Thompson1993) argued that they were also signs of resistance. What is perhaps most remarkable to note in relation to our new materialist rethinking is that these collars are not just embodied; they are speaking objects too, as almost all inscriptions are written in the first person. This points to interactivity, and the object as active messenger for the master (Trimble Reference Trimble2016, 462), but also of animism, where the master speaks for the slave through the object, but the object is the one that speaks. The collar testifies on a material level of the grim reality that the slave was indeed a thing rather than a human being. There is some immoral irony involved in thinking about this: the ontology of the enslaved according to Varro as being not more than a speaking tool, and the slave collar that takes over the speaking role, or extends this role, as a more authoritative voice than the enslaved. The collar becomes not only a dehumanizing fetishization of the human body, but is also a material conflation of ontological categories, where humans are objects that can speak, but not for themselves, and where animated objects must speak for them.

Figure 2. Bronze slave collar, ad fourth century with the inscription: ‘hold me, lest I flee, and return me to my master Viventius on the estate of Callistus’. (BM 1975,0902.6. Photograph: © The Trustees of the British Museum.)

Kinship alterity

According to Patterson upon enslavement, at birth or later in life, a person entered the social equivalent of the biological state of death. This ‘social death’ was the outward expression of what Patterson calls a slave's natal alienation, the severance of all ties of birth and kinship, of family and ancestors (Bodel Reference Bodel, Bodel and Scheidel2017; Patterson Reference Patterson1982). Although this term has been contested (see, for instance, Brown Reference Brown2009) as being too pathologizing and not taking into account lived experience, in terms of Roman kinship social severance and alienation are useful to consider when regarding it from a posthuman perspective. Roman enslaved were not always severed from ancestral ties and cultural heritage, since many were born into slavery; also, we know that in some cases relations with children and blood-ties of slaves were respected and maintained by the owners (Harper Reference Harper2011, 262–73; Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2011, 285–6). However, considering the value placed on (male) lineage and ancestry in the Roman world, having no birth or kinship in a normal Roman ‘human’ way must have had a profoundly alienating effect. The sensory openness that a posthuman perspective creates here, even when speculative, can make us think differently about the enslaved alternative conceptions of the body, kinship and personhood that exists parallel to the written sources. Combining this state of social severance with the occasional parahumanizing effect of a collar or a tattoo that marked the composite human, Allewaert's description of the existence of different modes of self and suspension of humanness also seems to apply when looking at kinship.

Alternative modes of kinship can be observed, for instance in the possible slave ideograms that Webster examined. These are shared symbolic markers occasionally found as graffiti used by enslaved groups, pointing to a form of communal language (Webster Reference Webster2008, 119–21). More directly it can be noted when reviewing burials set up by enslaved and freedmen in columbaria in Rome during the early imperial period, such as the columbarium-tombs of the Statilii Tauri or the Vigna Codini (Caldelli & Ricci Reference Caldelli and Ricci1999; Joshel Reference Joshel1992). The presence of these collective burials as shared afterlife spaces shows the existence of some sort of central organization, meaning that the enslaved (and the freed) occasionally formed communities themselves outside of what scholars have identified as the Roman ‘familia’. Furthermore, the inscriptions in these spaces do not distinguish individuals but point to a common affiliation, a common identity as a burial community (Borbonus Reference Borbonus and Wilson Marshall2014; Reference Borbonus2019). Generic names given to slaves by owners—such as Felix or Fortunata, numbers, or names from Greek mythology—slave professions such as attendants, valets, or physicians, and a homogenic language in the enclosed and shielded columbaria spaces enforce the idea that what we witness is not just collective practice, but collective belonging, and perhaps can be read not as a dismissal or acceptance of legal status but as a different personhood developing out of the experience of parahumanity. A different kind of kinship emerged, which also becomes testified in the many well-known freedmen tombs showing people freed from the same master who remained together, or the perhaps the Vetti ‘brothers’ in Pompeii, who might have been two ex-slaves from the same master sharing a house (Bodel Reference Bodel, Bodel and Scheidel2017; Severy-Hoven Reference Severy-Hoven2012). For Atlantic slavery such ties are often called ‘fictive kinship’, arguably not a good term, as it stresses again a western focus on blood relations as the only ‘real’ kin and undermines the parahuman personhood that established these ties as an ontological reality. It was such ties that became the very basis of the new African-American slave cultures, often starting from a shipmate bond, established among slaves on the Middle Passage and extended to their descendants on slave plantations, which became a major principle of social organization (Besson Reference Besson and Palmié1995, 187; Patterson Reference Patterson, Pargas and Roşu2017, 129). Even if Roman enslaved were tied to each other not on board of a ship but in other spaces, the ideograms, graves and freedmen culture show such kinship ties emerging in the Roman world, too.

Spatial alterity

For those people without objects, without human kinship ties, people that in some cases were seen as speaking objects or for whom objects were even speaking on their behalf, for some of these people we can perhaps see a personhood emerging differently in relation to the materiality of objects (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013, 118). A recent find of a slave room at Civita Giuliana, a villa discovered on the outskirts of Pompeii in 2020, has uncovered three beds for slaves, a chamber pot, eight amphorae, and a wooden chest containing metal and fabric fragments, thought to be horse tackle (see Fig. 3; also Osanna et al. Reference Osanna, Amoretti and Coletti2021; Osanna & Toniolo Reference Osanna and Toniolo2022, 147–70). Although many such rooms have been found in houses in Pompeii and Campania, the remains never have been so meticulously excavated before and we can finally get a more contextual and detailed sense of how the enslaved lived. A chariot shaft was found resting on one of the beds, belonging to a horse chariot found outside the room in the stable courtyard of the villa. The room was small, c. 16 sq. m.; the beds were of unequal sizes, two c. 170 cm long, one c. 140 cm long, suggesting that the room was shared by people of different age or gender (Osanna et al. Reference Osanna, Amoretti and Coletti2021). The archaeologists suggested the occupants of the room to be a family, and we might consider them so, whether they possessed biological ties or not: their existence in this space together must have forged exactly the kinship we just described that existed irrespective of any biological relations. The archaeologists also described the room as functionimg both as ‘a bedroom and a storage space’ (Osanna et al. Reference Osanna, Amoretti and Coletti2021). The eight amphorae and horse tackles, shafts and other equipment seem to confirm this; furthermore, the adjoining rooms showed more storage spaces, opening to the courtyard where the chariot stood, and a stable for the horses. The exceptional preservation of the room shows clearly how the amphorae are stacked in between the beds in the corner of the room, almost covering them, and how the other equipment is dispersed throughout the room. A few objects were found under the beds: an object interpreted as a chamber pot, and a few jugs, which the archaeologists assume were personal possessions (Osanna et al. Reference Osanna, Amoretti and Coletti2021; Osanna & Toniolo Reference Osanna and Toniolo2022).

Figure 3. Slave quarter at Civita Giuliana, room in a villa on the outskirts of Pompeii. (Photograph: © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.)

By interpolating the concepts of ‘family’ and ‘personal possessions’, it becomes clear how we as scholars are labouring to project a form of modern western sense of humanity upon this context which is—by any modern standards—inhumane, and the interpretation might be primarily a result of wishful thinking rather than an empirical judgement. If we assess the positions and distribution of the finds in the room, the conflation between object and human is overwhelmingly present. This room is not a ‘combination’ of a dormitory and storage space, this space is a storage space housing equipment both human and non-human. There is no boundary between where the storage ends and the bedroom begins, not made by the owners nor by the occupants of the room. Through the constraints of this room, a sense of ‘human’ personhood was denied to the three people (Bradley & Cartledge Reference Bradley and Cartledge2011, 2) and these enslaved can well be regarded to exist within what Patterson regarded a form of ‘institutionalized liminality’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1982, 13, 81–108) or the parahuman. Even if we do not have their voices preserved, what other personhood could emerge from this than a diasporic one, an entity whose component parts are always pulled into other exchanges, with specific equipment: chariots, horses and amphorae?

Representational alterity

The collar, columbarium and the storage room expand the current view on slave-being in the Roman world, but a new materialist interrogation is also able to create a different understanding of other (non-)human-object entanglements, such as slave-representations. Enslaved humans appear in a variety of artistic representations, in which both the aesthetic of the human body as well as the non-human status of the slave again becomes emphasized. Lenski argues that in art the slave performed as a tool as well, as such representations mostly appeared as functional objects of servitude such as incense burners, lamps, raising vessels, trays, even as a pepper shaker (Bielfeldt Reference Bielfeldt, Gaifman, Platt and Squire2018; Lenski Reference Lenski and George2013, 131). These art objects were aimed at the upper class, often slave owners themselves. Their anthropomorphic shapes, such as can be seen in Fig. 4, show either beautiful young (Greek) boys or Africans, mimicking those slaves that would serve drinks at banquets. Although such representations do not a priori belong to the enslaved, Lenski makes a convincing case to link the functionality of the object to the display of the captive body. The objects in this way materialize control and ownership, by ‘repackaging the human form into plastic symbols of the slave’ (Lenksi 2013, 136). This material form of servitude and glorification of the enslaved in art is not only an attestation of the slave as non- or parahuman by the free Romans; its materiality is an active agent in normalizing the ontological status of the enslaved. The slave was a tool and tools could be made to look like slaves.

Figure 4. Bronze statue of a slave boy holding a tray, ad first or second century. (MNAT 527. Photograph: © Archive Museu Nacional Arqueològic de Tarragona/R. Cornadó.)

Temporal alterity: ‘he who waits’

However, there exist representations of Roman slaves that are not functional or part of tool-being, such as those on wall paintings and mosaics, as well as in decorative, non-functional sculpture. In particular I am pointing to representations of the so-called ‘waiting slave’, a trope that was already popular in the Hellenistic period and which must have reflected the everyday reality of many Roman enslaved. In bath houses, in front of atrium houses (on those benches in front of many Campanian houses), during banquets, it would be common to see a slave—male or female—waiting for their master, and it is therefore not strange also to find this echoed in art (Fig. 5). Apparently, this was such a vital part of an enslaved's existence that we see it in art throughout the Roman world; from many Pompeian wall paintings showing slaves standing at the back behind their masters during dinner parties, or at bath houses, the famous Projecta casket where female slaves are depicted waiting alongside the central figure of a woman, or the mosaics from the baths of Piazza Armerina (Dunbabin Reference Dunbabin2003). During the waiting at banquets, the enslaved served as props to affirm the status of their masters present as guests. We know this from Roman literature where authors mention explicitly how dressed-up and expensive slaves were used to boast the master's wealth and status. Juvenal, for instance, writes about an ‘African Ganymede. A boy bought for so many Thousands hasn't the time to be mixing drinks for paupers’, and is ‘annoyed at having to answer to some old client who keeps asking for things, reclining there, while he stands’ (Satires V, 25–65). Hosting dinner parties was all about flaunting wealth through a lavish amount of food in an ornate room and garden, and through musings about the decorated slave we see how they were used as a portable form of ornament for those men not hosting. The part of the slave as a form of portable decoration, decorated himself to reflect the master's wealth, became decoration in art.

Figure 5. Marble statuette of an enslaved servant holding a lantern, waiting to escort his master home, ad first or second century. H. 16.8 cm. (MET 23.160.82. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.)

I have discussed the waiting enslaved's parahuman existence through representation in art; however, the position of the slave at the banquet goes beyond reflection, an artistic rendering of a master's idea of possession, but points to a more fundamental aspect of a Roman slave's embodied existence. A popular nickname for a slave was statius, ‘he who waits’ (Dupont Reference Dupont1992, 58; Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2000, 23), illustrating once more a parahuman sense of being. In addition to my previous arguments about people that could have possessed a different relation to themselves in sense of kinship, or in sense of their different relation to the material world, they were also firmly extracted from ‘human’ time, which belonged to their masters, not to them. Of course, there were strategies and choreographing on the part of the enslaved to escape this temporal colonization, such as the use of back-door alleyways we see in Pompeii, where they would not be seen or controlled by their masters (Joshel & Hackworth Petersen Reference Joshel and Hackworth Petersen2014, 99). However, under their control the enslaved must have lived much of their lives by waiting: Figure 5 and other objects portraying the waiting slave show that this probably often coincided with a particular posture, small and crouching (sometimes sleeping). Not only does this relate to a different temporal existence from non-enslaved; it also touches on a different ontological existence, as the slave was someone/something that had to simply ‘be there’. Surprisingly little has been written about the alternative temporalities that some of these Roman slaves lived. Even if not treated badly, or living with hope for manumission, all this must have been strongly overshadowed by the alternative temporal state of being ‘he who waits’. A different nature enforced upon a person by not being allowed to move, by having to wait, something entangling the body with place, tools and time.

To conclude this paragraph on slavery, I hope it has become clearer how in many instances the enslaved in the Roman world existed as a composite human: between object and human, where subjects and objects became recalibrated as different assemblages producing different personhoods through the relation of (para)humans, artefacts, spaces and ecological forces. Following these entanglements as a form of ontological difference should, of course, not lead us to conclude there was ‘a slave ontology’; however, accepting the body as a source of experience, accepting the agency of material realities in relation to the body and the sensory and temporal experience bound to the body, creates different natures,different modes of self, which result in different (multiple) ontologies (Harris & Robb Reference Harris and Robb2012, 676).

Conclusion

Navigating the green splendor of the sea … coming to light like seaweed, these lowest depths, these deeps, with their punctuation of scarcely corroded balls and chains … the entire ocean, the entire sea gently collapsing in the end into the pleasures of sand, make one vast beginning, but a beginning whose time is marked by these balls and chains gone green. (Glissant Reference Glissant1997, 6)

The Caribbean poet and theorist of decoloniality Glissant writes that corroded chains gone green on the ocean floor symbolically entangle the history and objects of slavery into the time of oceanic drift (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; see also Sharpe Reference Sharpe2016). Posthumanism that assumes a multitude of relationships among human and non-human beings can create openness and a presence where we normally see absence in the archaeological record. The chain cannot narrate a specific history of the enslaved it once held captive, but it does allow ‘historically informed speculations about the artifacts and persons who vanished without being included in traditional historical archives’ (Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013, 24; see also the work on critical fabulation by Hartman Reference Hartman2008). When ‘Objects speak for Others’, they speak about the fluidity that exists in Roman ontology. The reality is that objects can speak, that they are sometimes not just objects, and that some humans in some capacities are objects. This ontological fluidity adds to how we look at Roman religion but is especially useful in regarding Roman slavery. Examining the interrelations between objects, spirits, humans and other non-humans make it possible to bring a different understanding to Roman slavery that goes beyond the common archaeological approach of looking for visible traces in the material record. The entanglement of material and the unfree bodies of Roman antiquity is so intense that it would be absurd to dismiss any relational theory that can bring more emphasis, presence and depth to these experiences. A consequence of this study is that after such an interrogation we cannot unsee the darkness that speculatively resides in Roman material culture. Statements made in by Fernandez-Götz et al. (Reference Fernández-Götz, Maschek and Roymans2020, 1637) that there are dark and bright aspects of the Roman world and that ‘The bright aspects are often reflected in monumental public buildings, sumptuous elite residences, and developed infrastructure’ testify clearly how vital a relational and new materialism approach can be. There are objects and tools behind the construction of monumental public buildings, and a part of these tools consisted of human bodies. Legitimate criticism aside, new materialist approaches are useful because they make us look beyond superficial reflections derived from our modern binary ontology and lay bare the colonial inhumane slave economy that enabled the construction of every seemingly ‘bright’ monumental public building. New materialisms show the bleak entanglements of the non-human and through this break with traditional classical narratives. They can make us aware that the presumed archaeological silence or the bright versus dark dichotomy is a false narrative, that the realities and injustices of the Roman past can speak to us through every monument, through every brick, or mass-produced piece of glass or terra sigillata we encounter.

Through this article, I hope to have shown the potential of new materialisms and posthumanism for Roman archaeology in bringing a different framework with a renewed sense of alterity, one that might be able to make us better equipped to disrupt the false cultural intimacies we as scholars sometimes still project on the past by creating a lens that makes the Greeks and Romans less subject to western projections. The implicit assumptions of western rationalism need to be re-addressed and eradicated from our interpretations of the Greco-Roman past. Critical new materialism is not important because we need to write a ‘history of objects’; on the contrary, it is important because a better ontological positioning of the non-human and otherness, and the acceptance of ontological fluidity, can broaden our perspective on material culture and diverse social matters such as inequality, marginalized communities and coloniality in the Roman past.

Acknowledgements

First, many thanks to CAJ editor John Robb as well as the two anonymous reviewers involved for their very helpful comments. I further owe a huge depth of gratitude to Sandra Joshel and Jane Webster, two experts on the subject of Roman slavery who both gave me immensely useful feedback on that topic and also critically and constructively interrogated the posthuman and postcolonial ambitions of the paper. Many thanks are also due to Oliver Harris for his supportive and incredibly valuable comments on new materialism in archaeology. Lastly, thanks to my critical Roman archaeology interlocutors, Marleen Termeer and Rogier Kalkers for their help.