Impressions notwithstanding, professional baseball is strikingly similar to professional political science. Like baseball, political science requires the honing of unique skills. It demands stamina across multiple research projects scattered throughout a long work season. Advancement in political science also happens on the order of inches, with averages for successful outcomes (e.g., a publication) being surprisingly low. Indeed, much like a typical baseball player, the modal political scientist generally takes several at bats, hoping to land—after some setbacks—a research article accepted for publication at a respectable journal, thereby advancing their career.

However, the clearest similarity I observe between professional baseball and professional political science is the development of young talent that is drawn from places outside of their traditional bastions. In baseball, this has resulted in major-league teams fanning out across Latin America to successfully identify, recruit, and train many young Latino players. This increased presence of Latino players has a visible impact on what baseball players look like, how the game is played, and who actually watches this spectacle (Burgos Reference Burgos2007).

This is the spirit behind UCLA’s Race, Ethnicity, Politics & Society (REPS) Lab: to diversify political science. I established the REPS Lab in 2018 as a way to systematically identify and train young adults who aspire to break into the major leagues of professional political science research—young adults who generally are overlooked because they are viewed as too risky and not ready for prime time (Nonnemacher and Sokhey Reference Nonnemacher and Sokhey2022). The REPS Lab actively draws talent from these ranks of underrepresented, first-generation undergraduate students on campus, many of whom are women, racially minoritized, and/or queer (Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2020). Most REPS Lab affiliates are nonwhite students in a public university that is still strongly centered around white academics and peers. However, from where I sit, the affiliates represent an untapped pool of talent that can be trained to compete in political science. These students already have succeeded academically by operating in a research university that is incompletely matched to their unique experiences and still littered with social, economic, and political obstacles in their path. Their persistence and skill at adaptation are qualities that any political science PhD program should value. With focused mentoring, the REPS Lab refines these students’ talents so that they can answer important research questions.

This is the spirit behind UCLA’s Race, Ethnicity, Politics & Society (REPS) Lab: to diversify political science.

The remainder of this article discusses the REPS Lab’s origins and operations so that interested political scientists at other research universities can create a pipeline of fledgling political scientists from diverse backgrounds.

ORIGINS

I started my career in Vanderbilt University’s political science department in 2008. Some observers who were looking at my profile then would have expected me to flounder there. I am a highly identified Mexican American. Vanderbilt is located in the American South. I also was a greenhorn in a department filled with star recruits looking to increase that department’s national reputation. So how did I earn tenure there?

The honest answer is that I was intentionally mentored. Growing young faculty was part of the political science department ethos at Vanderbilt, epitomized by Cindy Kam. Through her Research on Individuals, Politics & Society (RIPS) Lab, she provided me as well as other junior faculty and her graduate students with structure, feedback, and professionalization (Druckman, Howat, and Mullinix Reference Druckman, Howat and Mullinix2018). I learned to incorporate feedback on my research, manage journal rejections, and convert “revise and resubmits” into publications. I also learned to manage my professional and family life without sacrificing either. Ultimately, I learned that if we want individuals to succeed within political science orthodoxies, then we must teach them the hidden curriculum that is required to thrive in our discipline. Brains and brawn are insufficient (Barham and Wood Reference Barham and Wood2021).Footnote 1

When I interviewed at UCLA in Fall 2017, I observed a campus filled with promising undergraduate students who lacked opportunities to develop their research skills. Either these students could not find a research mentor or the mentor with whom they connected operated in a hands-off fashion. The common denominator behind the frustrated undergraduate students I spoke with during my visit was that they were all the first in their family to go to college. This means that they obviously had the talent and tenacity to succeed academically, but they were not directly learning the expectations and norms of systematic research in our discipline (Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2020). Undergraduate research training thus became a key pillar of the REPS Lab.

OPERATIONS

The REPS Lab meets weekly, with 75 minutes allotted per meeting. This allows a maximum of two presentations by (under)graduate lab affiliates of a project in any stage of the process: a draft research design, a set of statistical results, a draft of a paper, or a grant proposal. These meetings occur every quarter and in the summer for six weeks.

A paid lab manager directs all lab communications about meetings, internal funding opportunities, and outside speakers. The lab manager also is responsible for programming studies and shepherding study applications for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. The lab manager typically is a senior undergraduate student or a recent alumnus taking a “gap year” before applying to graduate school.

The REPS Lab currently has its own office space at UCLA. It contains a separate room for lab meetings; carrels for three to four graduate students, including the lab manager; and a self-enclosed room with 18 laptops for highly controlled lab studies.

As of Summer 2022, undergraduate lab affiliates who join a team project are paid a $1,000 stipend for their work, which consists of 5 to 10 hours per week for six weeks during the summer session. This is when lab projects are significantly advanced in terms of data analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript writing. This stipend amount is also made available to undergraduate students working on their honors thesis under my supervision. In addition to this modest stipend, the lab collects original data for team projects and honors theses through reputable online survey vendors (i.e., $1,500–$2,000 per study).

Every summer, the lab works on three to five projects, inclusive of honors theses. Authorship on team projects is determined by degree of involvement in theory building, research design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. The more involvement across these areas, the higher the authorship rank, with consensus determining final author ordering. Generally, undergraduate students contribute to the original research design of a project and conduct preliminary analyses when data arrive. The fuller development of a theory, more extensive analyses, and writing usually are undertaken by the lab director, sometimes in conjunction with an advanced graduate student in the lab. Thus, the lab generally publishes papers with varying degrees of authorship with (under)graduate affiliates (see Vicuña et al. Reference Vicuña, Cass, Chua, Celine and Pérez2022 versus Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022).

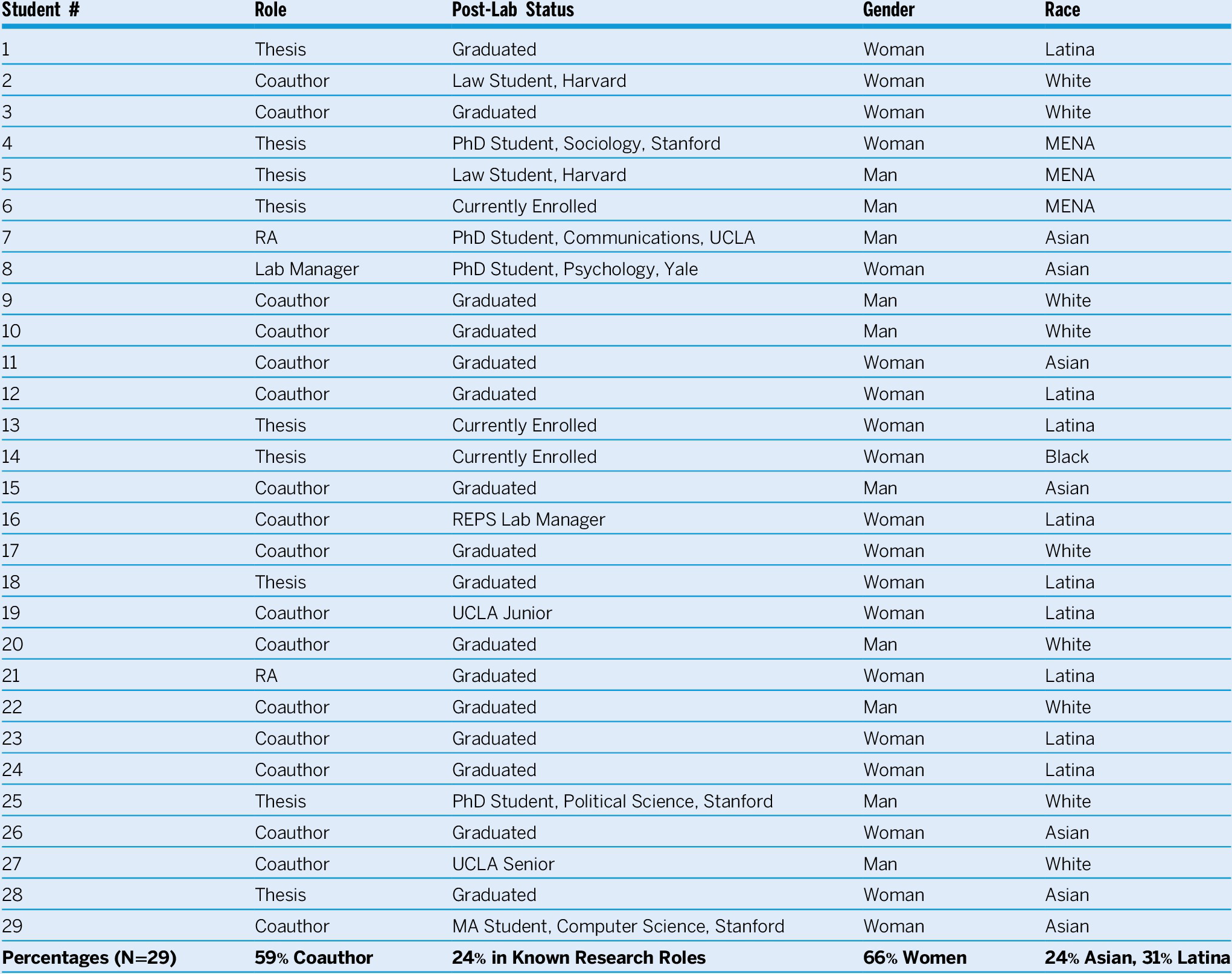

Table 1 lists key information about undergraduate lab affiliates since 2018. It excludes the approximately 15 doctoral students affiliated with the lab. Almost two thirds of these affiliates are women, which is notable given the many barriers—both external and self-imposed—that they face in the social and life sciences (Danbold and Huo Reference Danbold and Huo2017). The REPS Lab also is racially diverse, with Asian American and Latino students comprising almost 60% of these affiliates. Finally, most undergraduate students are affiliated with our lab through their coauthorship on a project, which means most of them actively work on a paper that ultimately yields professional gains for themselves and their peers.

Table 1 Characteristics of REPS Lab Undergraduate Affiliates (2018–Present)

Notes: RA=research assistant; thesis=honors thesis; currently enrolled=enrolled as a UCLA student; MENA=Middle Eastern or North African.

MEANINGFUL WORK

Research labs usually are organized around graduate students’ learning goals (Druckman, Howat, and Mullinix Reference Druckman, Howat and Mullinix2018). If a research lab recruits any undergraduate students, they tend to focus on that select segment of students with sufficient experience to facilitate research operations for principal investigators and graduate students. This is good from the angle of efficiency; it is horrendous if we want to produce young scholars who look like the people they eventually will serve as professors (Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2020; Nonnemacher and Sokhey Reference Nonnemacher and Sokhey2022). Some political scientists balk at the notion that descriptive representation has a place in the social sciences—we are supposed to be objective, after all. Indeed, I often hear that increasing the descriptive representation of students in research settings undermines meritocracy in our profession. However, as a political psychologist, I see too much data-driven research revealing that (1) the notion of meritocracy is an ideological myth that bolsters the racial status quo (Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999); and (2) descriptive representation psychologically optimizes people’s performance in professional settings (Danbold and Huo Reference Danbold and Huo2017).

…as a political psychologist, I see too much data-driven research revealing that (1) the notion of meritocracy is an ideological myth that bolsters the racial status quo; and (2) descriptive representation psychologically optimizes people’s performance in professional settings.

What I observe instead is a major bottleneck that dilutes the vitality of interests and perspectives that are essential to a valid and credible political science. This bottleneck stems from a lack of structured opportunities for undergraduate students to engage in original research and to begin learning the theory-building and data-analytical skills needed to seize subsequent opportunities (Druckman, Howat, and Mullinix Reference Druckman, Howat and Mullinix2018), including graduate school in the social sciences. Thus, working with undergraduate students of color is one tactic to win the much longer game of diversifying the academy (Sinclair-Chapman Reference Sinclair-Chapman2015).

Accordingly, the REPS Lab sensitizes undergraduate students to professional norms, including how to present research, incorporate feedback, write, and analyze and share data (Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2020; Nonnemacher and Sokhey Reference Nonnemacher and Sokhey2022). They also learn how to discern ideas that are worth their time. Any project that an undergraduate student joins or begins under my supervision is undertaken with the mutual understanding that the goal is to publish the results as a journal article, a chapter in an edited volume, or an entry in a professional handbook. This means that I negotiate ideas with undergraduate students, alerting them to the marks of (un)promising ideas.

MECHANISMS

Without close attention to selection procedures, lab membership naturally will default to those students who are the most comfortable asking to join (Nonnemacher and Sokhey Reference Nonnemacher and Sokhey2022). This section describes how the REPS Lab tries to improve on this practice.

Experiments Practicum

The main point of undergraduate entry into the REPS Lab is an experiments practicum that I offer to political science and psychology majors each spring: “Experiments in US Racial and Ethnic Politics.” I borrowed this idea from my graduate-school cohort-mate, Brendan Nyhan, who teaches an undergraduate seminar like this at Dartmouth College. The main differences between our courses are scale and setting. Professor Nyhan’s seminar consists of about 20 undergraduate students in a private institution; my seminar teaches 120 undergraduate students in a public university. This seminar unfolds at UCLA as follows:

-

• Each student is assigned to a team of approximately seven students (i.e., approximately17 teams). The teams work together on all course-related tasks, which sensitizes them to collaborative scholarship.

-

• Each team identifies a research question about US racial politics. I encourage students to “go with their gut.” Each team meets with me for 30 minutes to discuss their interests. We sharpen their question and I provide a list of readings for them to formulate a literature review (i.e., three nonredundant articles per team member).

-

• Each team drafts an experimental design to test a hypothesis implied by their question. The students have learned about experiments in my biweekly lectures, so they apply those lessons in this step. This process is nonlinear, but the goal is for them to acclimate to the trial and error of idea generation.

-

• Each team then produces a five-page proposal (i.e., double-spaced, exclusive of bibliography) that discusses what they are studying and how they will test their idea experimentally. This proposal integrates the literature that they read and distills it into a testable hypothesis. As a benchmark, students use archived proposals at the Time-Sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences platform.

-

• After submitting their proposals (by week 4), each team evaluates all of the projects except their own. We discuss each proposal in class to learn how to judge them scientifically. Each team is expected to integrate the feedback that they receive into a revised proposal. These revisions are described in a memo, with templates provided.

-

• With two teaching assistants (TAs), I judge the revised proposals and select one or two for which to collect data. The students whose proposal(s) “wins” are invited to join me on a team project(s) that we continue working on in the summer.

So, how good are these proposals? Remember, we are not evaluating established political scientists. By that metric, these proposals fall short of expectations. We are judging individuals who are learning to express and justify their ideas. It is crucial to provide actionable feedback, without paralyzing the students. This is difficult to do. Thus, I evaluate these proposals in class by providing clear feedback and encouragement—I candidly tell them what can be improved and why it should be improved, and I suggest concrete ways to improve the proposal. I also remind them that they are being graded—not on how blemish-free their proposals are but rather on how responsive their teams are to the feedback that they receive.

Ultimately, the strength of the student proposals is that they identify a research question that, with my help, is further refined and anchored in a literature. These proposals also identify the main elements of a research design, which I then improve on so that a study most likely will yield interpretable (null) results.

While we wait for our data, the class continues to learn more about experiments, including their analysis and interpretation. Two TAs teach basic programming in R. The students also learn other elements of research practice, including data sharing and open analyses. All of this is done with concrete examples from my own work; each student is given a template needed to accomplish these tasks, including data and batch files from previous projects of mine.

After the data for a study arrive—approximately three weeks after a proposal is selected and IRB approved—all research teams and the instructor are responsible for co-analyzing the data in class. My goal is to sensitize the students to the promise and perils of data analysis while demonstrating one way to evaluate the robustness of any emergent findings. With (null) results in hand, each research team writes a brief research paper (i.e., approximately 4,000 words). The winning team(s) is invited to join me in the summer to continue advancing the project toward publication, which often necessitates additional data collection and analyses as well as at least one round of rejection by a journal (some students decline this invitation).

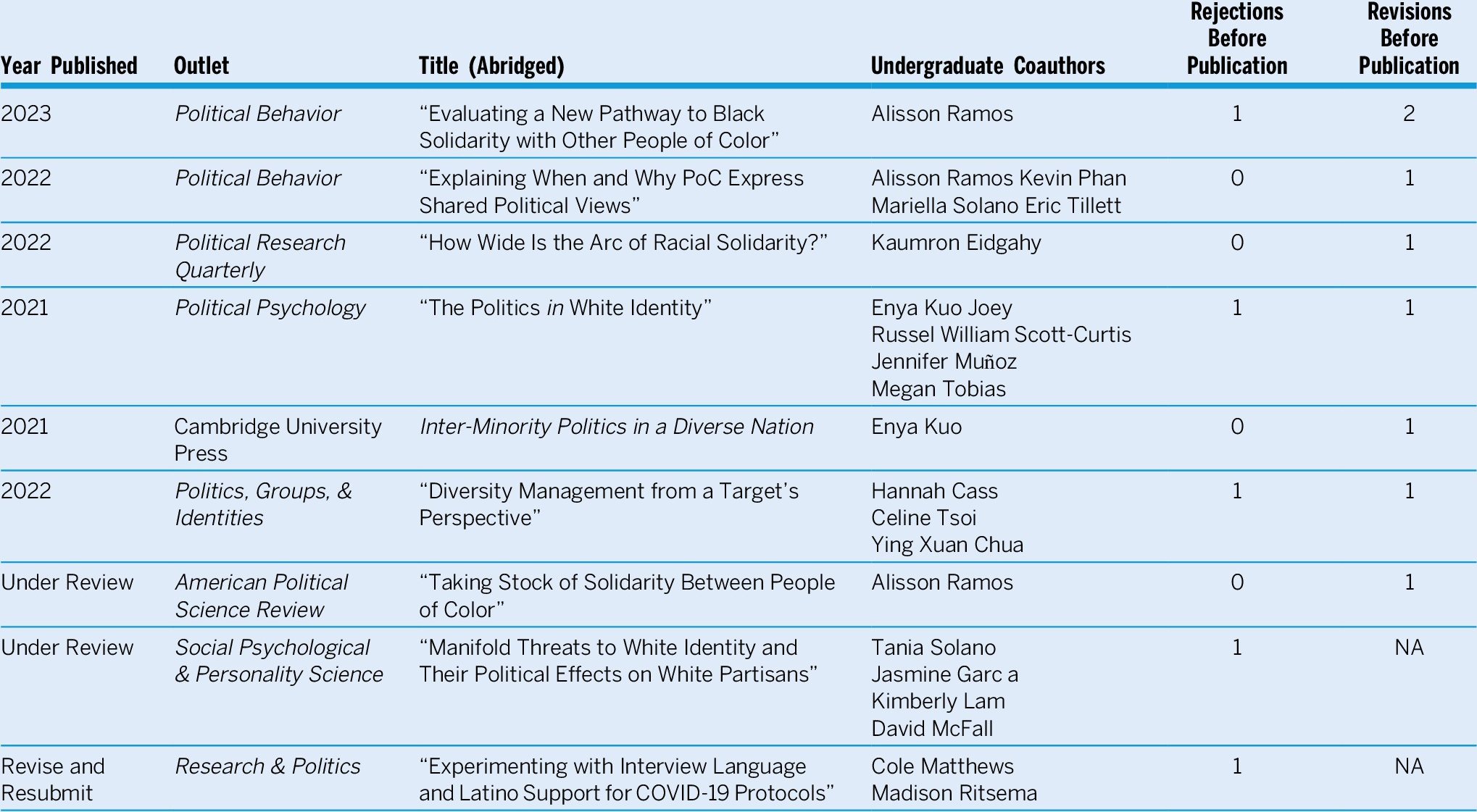

These efforts ultimately yield four to six undergraduate students who become coauthors on a team project(s) arising from this practicum. Of the four times that I have taught this course since 2018, we have published one book and five papers, with three additional manuscripts currently under review. Table 2 lists these manuscripts with full author names and the number of rejections before publication. These undergraduate students have earned coauthorship by actively participating in the formulation of the initial idea, creating the basis of a literature review, and conducting basic statistical analyses.

Table 2 Published Papers with Undergraduate Coauthors (2018–Present)

Notes: NA=not applicable. Entries include published and papers under review. Graduate-student coauthors are omitted from projects to focus on undergraduate coauthors.

Honors Theses

A less common route to join the REPS Lab as undergraduate students is through honors theses that I supervise. They have taken another course with me (i.e., Political Psychology) or have worked in the lab as a research assistant (RA). Their interest in doing original research has been sufficiently sparked that they want to do an independent project.

The expectation I set for each honors thesis is that it will include an original data collection and hypothesis test. This pathway starts in the summer before an honors thesis is due, which is in the spring quarter of the upcoming academic year. Students use the summer to read intentionally and identify which theoretical blind spot their project will address. They also present their initial idea during our summer lab sessions, with the expectation that in the fall quarter, they will begin data collection, which the REPS Lab funds. Two lab papers have been published that originally began as honors theses and eventually morphed into larger team projects (see table 2, Eidgahy and Pérez Reference Eidgahy and Efrén O.2023; and Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022 in Political Behavior).Footnote 2

SUSTAINMENT

None of these efforts is free. If we expect undergraduate students to conduct quality research, they will need to collect quality data including surveys, experiments, and in-depth interviews. Depending on the nature of a study, a single data collection can cost from $500 to $2,000. I have negotiated the funding for this operation in three ways. The first infusion of support came from my negotiations to move to UCLA from Vanderbilt University. I persuaded the Dean of Social Sciences that a research lab was in the interest of political science specifically and undergraduate education more generally. UCLA considers itself a harbinger of mobility, with its public aspiration to soon be a Hispanic-Serving Institution testifying to this principle. The REPS Lab contributes to this goal by opening doors to research skills and careers that students expect. At present, several lab alumni have transitioned to managing another lab or doctoral study in competitive political science and psychology programs (see table 1).

Second, I bolstered the lab’s financial reach by renegotiating my research support in light of outside job offers. Much can be renegotiated in this situation. My priority has been to extend our lab’s longer-run viability, which requires advocating for a steady pipeline of undergraduate researchers.

Third, the lab is sustained through regular grant opportunities inside and outside of UCLA. Since 2018, I have learned that some undergraduate students are sufficiently detail oriented to work as lab managers—a post normally reserved for advanced graduate students. Our inaugural lab manager assumed this role as a UCLA senior and our current lab manager is a recent UCLA alumnus who is taking a gap year before entering a PhD program. With a $25,000 grant from UCLA’s Latino Public Policy Institute, I converted this role into a more structured learning opportunity by paying lab managers to codirect the lab with me while they actively prepare for graduate school.

UNEXPECTED CHALLENGES

Well-intentioned plans often encounter unexpected challenges, and the REPS Lab is no different. One major challenge is that despite our racially diverse lab membership, we have not made as successful inroads among Black political science and psychology majors at UCLA. I have intentionally addressed this pattern by encouraging, during office hours, Black undergraduate students to consider doing an honors thesis under my supervision (e.g., Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2020; Nonnemacher and Sokhey Reference Nonnemacher and Sokhey2022). As of this writing, this has yielded one African American student who currently is completing an honors thesis on anti-Black prejudice among US Latinos.

Another challenge is ensuring that undergraduate students directly produce social science research but without limiting their access to other professional opportunities. UCLA undergraduate students generally have busy extracurricular schedules, which means that our lab projects are competing for attention with other opportunities. This is why the REPS Lab began offering undergraduate affiliates a research stipend: to honor their time on a project for a clearly bounded set of summer weeks.

Finally, a continuing challenge is organizing teams of undergraduate researchers who possess complementary skills. This may happen organically, with research teams assembled (at random) in my experiments class, yielding a mix of psychology and political science majors. However, this does not consistently produce an even combination, for example, of statistical programming and writing skills. One way that we address this is by incorporating into a team an advanced graduate student who has the skill set that directly strengthens a project.

WRAPPING UP

One incentive for directing the REPS Lab is its direct alignment with UCLA’s goal of producing and supporting scholarship in the public interest, which facilitates funding for our undergraduate activities. Another incentive is that UCLA’s political science and psychology departments have made my experiments research practicum count toward each major’s credit in undergraduate methods training. Of course, there also are disincentives. A major one is the substantial amount of time needed to run team meetings, coordinate data collection, and produce papers that can contend for publication. Therefore, when making the decision to create and direct a lab, be aware that it will be time consuming with tradeoffs in terms of forfeited or forgone professional opportunities in prioritizing a lab, its affiliates, and their activities.

One incentive for directing the REPS Lab is its direct alignment with UCLA’s goal of producing and supporting scholarship in the public interest, which facilitates funding for our undergraduate activities. Another incentive is that UCLA’s political science and psychology departments have made my experiments research practicum count toward each major’s credit in undergraduate methods training.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.