[The ‘texts’ referred to in the title are primarily literary texts in Antiquity in the form of papyrus rolls and codices. Literary manuscripts, as I say in the article, came increasingly to resemble the book forms that we are familiar with, but for the most part this did not begin to be the case until the early Medieval era. The book form as we know it did not really exist until books ceased to be written by hand. As I also point out, writing conventions in Antiquity were not fixed and uniform, especially with regard to letter forms, punctuation, and word/sentence/paragraph etc. separation. On all such matters see, with bibliography, Chapter 2 by Rex Wallace in A Companion to the Latin Language (Wiley-Blackwell 2011). See also Chapter 4 of the same book by Bruce Gibson, especially the section on punctuation.]

ὥσπερ ἐκλογὴ τῶν ὀνομάτων εἴη τις ἂν ἡ μὲν πρέπουσα τοῖς ὑποκειμένοις ἡ δὲ ἀπρεπής, οὕτω δή που καὶ σύνθεσις [Just as a choice of words may be appropriate to the subject-matter, and inappropriate, so surely may an ordering of them be also] (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, On The Arrangement Of Words 20).

denique quod cuique visum erit vehementer dulciter speciose dictum, solvat et turbet: abierit omnis vis iucunditas décor. [Finally, what will have seemed to each person to be said forcefully, sweetly, elegantly, let that person break up and disarrange: all its force, charm, grace will have gone] (Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 9. 4.14).

‘Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in their best order.’ (Coleridge, Table Talk).

Coleridge was, of course, assuming that the words would be able to be read. We are aware that the format of an ancient literary text was very different from that of its modern counterpart: that a papyrus roll (held in the right hand and unrolled with the left hand; there seems to be confusion about this) was a very different thing from a book. And, apart from a superficial similarity of appearance to a book, the format of a codex had more in common with that of a roll than a book. However, we are not always aware of the implications this difference of format may have for our respective experience of a text, our own through reading, that of the Greeks and Romans often by hearing rather than by reading.

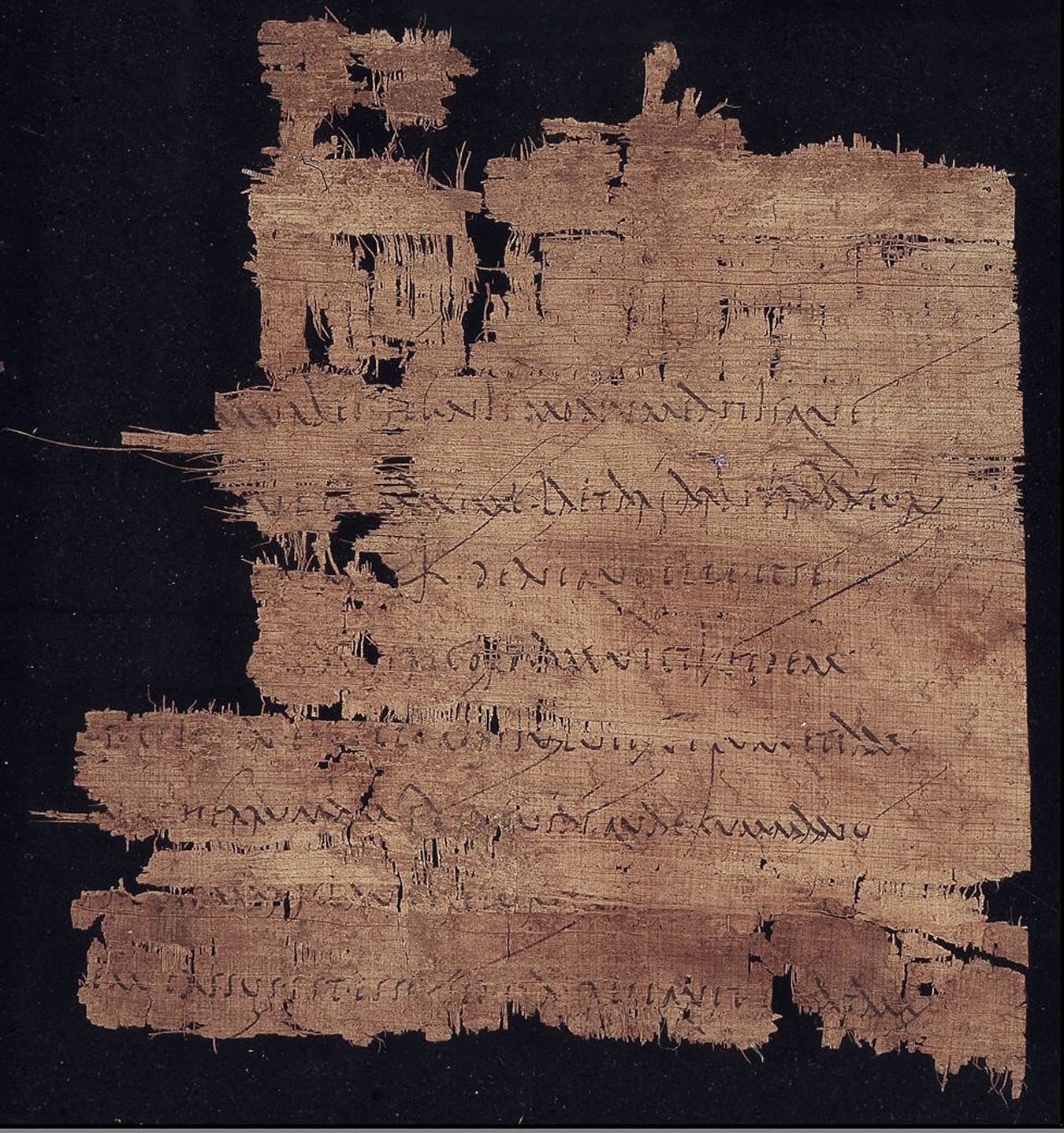

The oldest extant Greek literary text is a substantial portion (about 250 lines) of the Persae of Timotheus that is dated to the second half of the fourth century BCE. The oldest extant Latin literary texts date from the late first century BCE to the first century CE; the oldest, according to Bernard Bischoff (Reference Bischoff1990, 57) is probably a fragment from Cicero, In Verrem 2. Both can be viewed today (see Figures 1 and 2 at the end of this article). When set alongside the same texts in modern printed editions the differences of presentation are striking. You would hardly know that the Timotheus fragment was verse rather than prose.

Figure 1. Timotheus, Persae.

Figure 2. Cicero, In Verrem 2. 3–4.

There are many books, monographs and articles that deal with word order in ancient Greek and Latin, including books in ancient Greek and Latin, e.g. Demetrius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Quintilian (see the extracts above). But none of them, as far as I am aware, approaches the subject of word order in the way that I propose to do in this article. Generally speaking, they treat word order as a linguistic phenomenon rather than, as I do here, a psychological or a sociological one. They are more concerned with the forms and patterns of appropriate and effective word order, or of typical and untypical word order, treating it as an objective feature of a text (as, in an obvious sense, it is). I am more concerned with the extent to which, and the means by which, people were actually able to be aware of instances of word order as a literary device, and of its effects; and what difficulties may have hampered awareness of it, difficulties mainly to do with the format of ancient texts and the ways in which they were accessed.

In inflected languages such as Greek and Latin, word order plays a minor role in conveying (cognitive) meaning. This being the case, word order can be varied much more in an inflected language without affecting the ‘basic’ meaning. One of the purposes to which a more flexible use of word order may be put is the creation of literary effect. Obviously, this effect can only be achieved if the writer is able to draw the attention of the reader (or listener), without undue effort on the reader's (listener's) part, to the order in which the words have been arranged. Generally speaking, displacing a word from its ‘usual’ position will serve to draw more attention to it and thereby to emphasise it in some way. But word order must first be able to be perceived, visually (or aurally), before its effect can be experienced, analysed and appreciated. This may be a truism; if so, it is one that we must not lose sight of.

Word order as a literary effect/device, which we are apt to make much of, may not have been so evident to a reader (or listener) in the ancient world, and therefore may not have had the effect on an ancient reader that it has on the modern reader of a modern printed edition. The visual appearance of a literary text in the ancient world was very different from the way in which it appears in a modern printed edition. It should be borne in mind that our observations on word order and its efficacy are based on the presentation of the text in a modern edition, not on the text as it would have appeared on an ancient roll or codex (or on a medieval manuscript). The differences of format and presentation are well known, and include, amongst other things, the following features of an ancient text: absence of word division (scriptio continua) (but are words any more divided in speech? Is there any more division between spoken words than between syllables of a spoken word?); capitalisation; absence or minimum use of punctuation; little or no (visual) division into sentences or larger structural segments. One might also mention the inability to draw attention to individual words by means of such modern formatting devices as highlighting, underlining, capitalisation, bold or italic fonts etc.Footnote 1 In addition, verse, or certain types of lyric verse, mainly before the Hellenistic period – epic and drama were set out more or less as they are in a printed edition – was not arranged in clearly distinguishable lines that displayed its metrical structure. These differences, we suppose, would surely have worked against a ready reception by means of sight alone of literary effect as a function of word order.

The language, ideas and manner of expression of ancient literary texts (think of Pindar and Persius) probably made them difficult enough in themselves for anyone except the most practised Greek or Roman reader to read at all fluently, without what seem to us like additional problems presented by the format of the texts. As Mary Beard says in her blog A Don's Life (11 August 2016), ‘Most of the classics we have to read in Latin, or Greek, are so damn difficult … and it was probably almost as bafflng for native speakers too’. And she is (presumably) writing about the small minority of literate and educated people who had access to such texts, not to all ‘native speakers’ of Latin and Greek, most of whom were illiterate or whose level of literacy did not embrace literary texts with carefully crafted word order.

Literary works were read aloud, either to oneself or to an audience of some kind, much more commonly in the ancient than in the modern world, even if this may not have been the norm for solitary, private reading, as is often supposed.Footnote 2 Reasons for being read aloud, especially to an audience, may have been the difficulty experienced by many/most people in reading them silently for/to themselves; or in the paucity of available copies for individual reading. In Greece there were few books and few people able to read them before the end of the fifth century BCE. Most of what was written was intended for oral delivery to an audience of some kind. Archaic Greece and the first half of the Classical period was a mainly oral/aural culture as far as the reception of literary texts was concerned. This hardly indicates a widespread facility in detecting nuances of word order by means of sight alone.Footnote 3 Given the practice of reading aloud, the (presumed: but see note 3 below) difficulties involved in reading at all, and the fact that many people may only have experienced a text aurally, by having it read to them, is it not likely that the writer intended any effect of word order to be conveyed not so much by the visual arrangement of the words ‘on the page’, as it were, as by the sound of the words, e.g. by emphasising the positioning of words by increased or diminished volume on the part of the reader, by pauses, even by means of facial or bodily gestures as well as by sound. What does seem likely is that word order and its effects were not registered primarily by sight, as is the case with a modern reader, and that, because of the difficulties inherent in discriminating the spoken word, many instances of word order may have gone undetected and their effects unappreciated.Footnote 4 On the other hand, if people in antiquity were more used to hearing than reading a text, perhaps their aural reception of the text was more acute and more sensitive than ours, so that they were able to experience aurally effects of word order that would be closed off to us who identify them by visual position alone.Footnote 5

To conclude: the awareness and appreciation of word order used for literary effect was perhaps more elusive for most recipients of literary texts in antiquity, either when reading or listening, unless their powers of reading and listening were much more adapted than ours to the particular problems posed for them by the format of an ancient text. The frequency of the conspicuously (to us) creative use of word order suggests perhaps that ancient readers' powers of reading and listening were so adapted – presumably the authors of the texts thought so. Or perhaps personal satisfaction with their own achievement was sufficient for them. After all, how many people were aware of the detailed intricacy of workmanship that went into the frieze of the Parthenon or Trajan's Column? And how many people in more recent times have been aware of the details of much of the art work on many buildings and monuments, let alone the inscriptions?