By the end of the eighteenth century the Bank of England was firmly entrenched as banker to the state and manager of the state's debt (Bowen Reference Bowen, Roberts and Kynaston1995). Thus, as the rising costs of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815) put pressure on Britain's financial systems, the burdens placed on the Bank increased. Aside from the additional financial support it offered to the state, the stresses on the Bank manifested most clearly in increases in its workload. In its position as primary manager of the public debt, it had to cope with rising numbers of public creditors demanding prompt attention when they wished to sell or purchase government stocks or collect their interest payments and dividends. Throughout the war period, the Bank had also to manage a vastly increased discounting business. As Clapham notes, the average amount of bills of exchange discounted had only been a little over £2.5 million in 1794 but by 1807 it was over £13 million per annum (Clapham Reference Clapham1945, ii, p. 11). Perhaps most problematic for the Bank was the management of its banknotes after 1797 when, as a means of protecting its gold reserves, the Bank suspended the convertibility of its notes. The suspension resulted in a significantly increased note issue and extended that issue, for the first time, to small denomination notes (Clapham Reference Clapham1945, ii, p. 5; Newby Reference Newby2012). One of the unintended consequences was a rising tide of forgery. The newly issued £1 or £2 notes were a magnet for criminals, but the peculiarities of the eighteenth-century legal system made the Bank not only victim but also detective and prosecutor. This required a significant operation to manage not only note issue but also identification of forgeries and detection and prosecution of the forgers (McGowen Reference Mcgowen2005, Reference Mcgowen2007; Wennerlind Reference Wennerlind2004).

The result of this rapid expansion of the Bank's various businesses was an urgent need to increase its workforce. From a complement of around 300 in the mid 1780s, the number of clerks employed had increased to over 900 in 1815 (Giuseppi Reference Giuseppi1966, p. 56; Kynaston Reference Kynaston1995, i, p. 30). This undoubtedly made the Bank's staff the largest concentrated white-collar workforce in the world. Much like a civil service, together the Bank's clerks constituted a body of knowledge and experience that remained constant while directors and governors of the Bank came and went. Each operated in a specialised capacity in offices supervised by senior colleagues, and heavily coordinated with each other, thus making the organisation of work at the Bank akin to that in a large factory. Individually, the jobs those clerks performed were mundane and repetitive but collectively the feat they achieved, that of managing the national debt and providing banking and discount facilities for London's business and financial community, was nothing short of extraordinary. Moreover, this was a labour force that, until the advent of the typewriter and the automated bookkeeping machine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and indeed, arguably until the advent of the computer, could not be replaced or even significantly aided by technology. Their work was done by hand in processes that involved the endless recording of details in ledgers and checking and double-checking to ensure the integrity of the records.

Although the skills of London's financial workforce have been acknowledged in recent studies, little attention has been given to the development and quality of those skills (Cassis Reference Cassis2006; Michie Reference Michie2008). Perhaps because of a scarcity of sources, the classic studies of banking development and the institutional histories of individual banks have given little space to the work of the clerks (Akrill and Hannah Reference Ackrill and Hannah2001; Checkland Reference Checkland1975; Crick and Wadsworth Reference Crick and Wadsworth1936; Pressnell Reference Pressnell1956; Sayers Reference Sayers1957). Nor indeed has the eighteenth-century emergence of the white-collar worker commanded the attention of historians. Indeed, McKinlay dates the emergence of the ‘banking career’ as late as the 20 years prior to 1914 (McKinlay Reference Mckinlay2002). Even when they have been considered, early clerks have been characterised as a ‘marginal group’ (Heller Reference Heller2010, p. 1). In consequence, most of the historiography has concerned itself with the lives of Victorian clerks, especially during the later nineteenth century when their lifestyles and status supposedly came under threat from a rapidly expanding potential workforce, the seeming downgrading of the status of clerical labour and eventually the influx of women into clerical work (Anderson Reference Anderson1976, Reference Anderson1989; Heller Reference Heller2010; Lockwood Reference Lockwood1958; Orchard Reference Orchard1871).

This article offers an insight into a much earlier set of white-collar workers through an examination of the backgrounds and skills of the men interviewed by the Bank of England between 1800 and 1815, a period when both it, and the banking sector more generally, was undergoing significant expansion (Pressnell Reference Pressnell1956, p. 11). It draws on a unique set of sources preserved in the Bank's archives. These include ledgers containing details of the initial interviews with applicants for clerical positions. The ledgers covering the period from 1800 and 1815 include 794 interviews with 729 unique individuals: 91 sons of former and current clerks and 638 men with no familial connection to the Bank. Although the exact details recorded during each interview differed, the ledgers generally recorded some standard information, notably place of birth, age, religion and marital status. Candidates were also asked to confirm that they were free from debt and that they did not belong to any associations, such as political clubs. In many cases candidates provided information about their schooling and previous career histories. Some also gave details about their families, including their father's or mother's occupation. The interview ledgers can also be cross-referenced with separate ledgers in which were recorded the results of tests performed by each applicant. Not all candidates can be traced in these ledgers but test results can be found relating to nearly 600 of the 794 interviews thus offering a significantly large sample from which to draw conclusions. Together the two sets of ledgers allow the construction of a detailed picture of the labour force available to the early nineteenth-century Bank of England.

The men who emerge through these records may have been a marginal group when measured against the rest of London's, and indeed Britain's, early nineteenth-century workforce (Lindert and Williamson Reference Lindert and Williamson1982, p. 400), but they were highly significant at a point where sound management of the national finances was key to British military and geopolitical success. Trust in public finance and a newly established paper currency rested largely upon the efficient functioning of the Bank and thus ultimately on the shoulders of the Bank's clerical workforce. This article is the first to explore this aspect of the functioning of the fiscal-military state and also the first study of early nineteenth-century white-collar workers. What follows will firstly explain the Bank of England's recruitment process. Section ii will discuss the clerks' backgrounds. Sections iii and iv will focus on skills, considering the broad scope of skills to be found among the potential workforce and the results of the Bank's tests of its applicants. Section v will consider the means used by the Bank to bridge the obvious gaps between the skills it required of its workers and those possessed by applicants for its posts. Finally, section vi concludes.

I

Employment at the Bank of England was attractive. The Bank offered a regular salary that compared very favourably with other similar work and was paid quarterly in cash, something that was not always available to other workers (Boot Reference Boot1991, Reference Boot1999).Footnote 1 By 1800 it was also acknowledging that it was impossible to get by on less than £100 per annum and, therefore, it supplemented salaries that fell below that point through gratuities that could be earned by diligence and regular and timely attendance (Acres Reference Acres1931, ii, p. 351). Pay could be further enhanced in some offices by payments for overtime, bonuses paid by the Bank, and gratuities from grateful customers. Over the long term, earning potential was very good with salaries rising in regular increments once an initial, and informal, training period had been completed. The taking of a second job was also permitted so long as it did not interfere with work at the Bank (Acres Reference Acres1931, ii, p. 362). Moreover, although there were some redundancies after the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, for the most part, work at the Bank offered job security. The Bank's directors allowed clerks to work well into their old age. It also granted generous pensions to those who it let go or who wished to retire and to those who were unable to work through accident or physical or mental incapacity. A lifetime's career in the Bank of England would ensure a secure place in the middle to upper middle ranks of society (Boot Reference Boot1999, p. 658). For all these reasons, although, as we shall see, there might have been a shortage of the precise skills required by the Bank, each vacancy could certainly have been filled by a willing hand many times over.

There was, however, no public advertisement of vacancies at the Bank. Men could only be considered by recommendation of one of the directors or by virtue of being the son of an already long-serving employee. It seems probable that many of the directors had a fairly steady stream of young men making contact with them and they chose the most promising, most well-connected, or the most pushy, of those men to put forward when an opportunity presented itself. As such, access to a position at the Bank, initially at least, was about who you knew, and how well you were able to exploit that connection, rather than what you knew. This was certainly typical of employment practices in other similar businesses, such as insurance and the East India Company (Bowen Reference Bowen2006, p. 141; Supple Reference Supple1970, p. 71). But it does not mean that employment practices were poorly considered or determined solely by patronage. The social bonds that determined introduction arguably acted as a strong initial screening mechanism and, in the longer term, may have reduced the risk of malfeasance. In industries like banking and insurance, therefore, personal recommendation continued to be a common requirement for employment well into the twentieth century (Anderson Reference Anderson1976, p. 12; Heller Reference Heller2010, p. 144).

The Bank's recruitment procedures had always been quite rigorous (Murphy Reference Murphy2010). From the early nineteenth century, however, procedures were enforced with greater vigour. After 1800 when it required additional hands, the Bank appointed a committee from among its directors to interview the applicants. As an introduction to the Bank each candidate was asked to prepare a petition outlining his fitness for the position. Unfortunately, none have survived in the Bank's archives so the precise nature of these documents is not known. This also means that we have little information about the reasons why the candidates had applied to the Bank, except when the more unusual cases were noted in the interview record. Surely Walpole De St Croix was somewhat ill advised in the claim he made in his application that he wanted to give up his position because he felt himself aggrieved when his current employer had docked his wages for being late to work a few times.Footnote 2 William Smithyman was on equally shaky ground when he informed the committee that service at sea for the East India Company had convinced him that he was ‘better leading a sedentary life than an active one’.Footnote 3 Those candidates whose reasons were not deemed worthy of record must have instead emphasised the attractions of a steady wage, long-term job security and the prestige of working for the country's premier financial institution.

On the day of the interview each candidate was subject to a test, conducted by the chief accountant, of the candidate's ability to deal with money, an interview with a committee of the directors, and was then asked to provide a sample of his writing and work with accounts in front of the committee. On completion of the interview and testing process, the committee made their recommendations which then went forward to the Court of Directors. The final decision to employ or reject rested with them. Nonetheless, failure to secure employment at the first attempt was not necessarily the end of the story. Many men made a number of applications to the Bank, often working in the interim to repair any defects noted by the interviewing committee.

Of those who were rejected by either the committee or the Court of Directors, age was one stumbling block. From 1800 the Bank set a minimum age of 17 and a maximum age of 30 for its applicants. Thus Frederic Reid was rejected at his first attempt to enter the Bank because he was not yet 17.Footnote 4 Some candidates were found to be unqualified. Hence George Lettis who had worked as a warehouseman, run the Spotted Dog public house in the Strand and then worked for six months for a militia insurance office was ‘Disqualified from his want of ability and also on account of the situations he has held’.Footnote 5 Only one man was rejected because of a physical disability: Charles Burrows was found to have a serious speech impediment, so much so, that he took his father to the interview to speak for him. His recommendation was later withdrawn.Footnote 6 Some men lost their chance by succumbing to anxiety. James Westerman, aged 28, from Kilkenny in Ireland was ‘so nervous that he could not multiply a sum’. His name did not go forward to the Court of Directors.Footnote 7

Overall, however, the rejection rate of applicants to the Bank was very low. Over 90 per cent of the men interviewed during the period under consideration were offered employment. Although giving the impression that the process lacked rigour or was merely a rubber-stamping of favoured directors' choices, as the following section will demonstrate, the interview process was challenging. The low rejection rate was, in fact, symptomatic of another factor: during this period the Bank was expanding rapidly and the skills it required were in short supply.

II

The details preserved in the Bank's interview records allow us to construct a detailed picture of the candidates who applied for positions. The average age of those with no familial connection to the Bank was 21.60 and the average age of those applicants who were sons of former or current clerks was 18.64. The age range of the applicants was between 16 and 34. Those who were under-age at the time of initial interview were usually invited to return when they were older. The upper age limit of 30 was sometimes relaxed. It is clear that the committees were aware of the possibilities of cheating the system. William Gibbs was fortunate to be able to produce proof of his age as the Committee noted that he looked unusually young.Footnote 8 John Wall, apparently aged 29, was suspected of having altered his certificate to get past the Bank's upper age limit.Footnote 9 Nonetheless, there are a number of indications that age was difficult to prove, and sometimes difficult to know, in a period prior to the introduction of compulsory registration of birth. Thus, John Way, a Trinitarian, was unable to produce a certificate of his age and had instead produced an affidavit signed by his father in the presence of the Lord Mayor.Footnote 10 This was not just a problem for dissenting Protestants. Samuel Frame was unable to find the register of his birth despite having looked through the books of several parishes.Footnote 11

As Table 1 shows, the majority of applicants to the Bank were born in London and the south-east suggesting, as might be expected, a largely regional market for clerical labour. Nonetheless, there were also a number of applicants drawn from all over the country and from farther afield. This should not surprise. The draw of London for economic migrants, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and indeed much earlier, is well established (Harding Reference Harding1990; Wrigley Reference Wrigley1967). London remained, even by the early nineteenth century, the driving force behind Britain's economy and the place where the highest concentration and variety of jobs could be found. London also drew in workers from outside Britain's borders and thus the Bank attracted candidates who had been born, grown up and even started their careers in Britain's nascent empire and other major centres of trade. Thus, applications were received from men born in Hamburg, The Hague and Bruges.Footnote 12 John Joseph Blake was born and grew up in the East Indies.Footnote 13 Cheney Hamilton and John Robertson were both born in Jamaica.Footnote 14 The candidate from farthest afield was Henry Martin Johnson born in 1792 in New Holland (Australia). Henry was the son of Reverend Richard Johnson, the first clergyman to serve the new congregation of convicts and their guards.Footnote 15 Henry must have been one of the first European babies to be born in Australia.

Table 1. Place of birth of applicants to the Bank, 1800–15

Source: BEA, M5/406–8, passim.

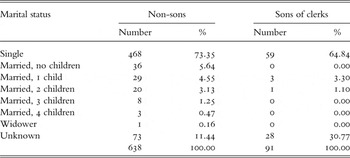

As might be expected of a cohort that included men in their late 20s and early 30s, some of the men applying to the Bank between 1800 and 1815 were married and many of those had children. Table 2 shows the marital status of the applicants. There is no evidence that the Bank preferred married men, indeed the majority of the applicants were single: 73 per cent of applicants with no familial connections to the Bank and 65 per cent of the sons of former clerks. There are, however, some indications that the interviewing committees might have harboured doubts about the stability of young, single men. Hence 17-year-old Henry Pownall's father reported to the committee that his son was ‘very steady and not inclined to Company’.Footnote 16

Table 2. Marital status of applicants to the Bank of England, 1800–15

Source: BEA, M5/406–8, passim.

As Pownall's father's assertion suggests, the ideal clerk was a man whose reputation held no hint of poor behaviour, profligacy, temptation to fraud or embezzlement nor indeed the likelihood of political or religious activism. All candidates were asked about their religious and other affiliations that might have conflicted with their loyalties to the Bank in its own regard and as representative of the state. And all men were questioned about their financial stability.

As Table 3 shows, the majority of men were of the established church. Various denominations of dissenters were represented and their relatively high showing among the sons of clerks suggests that the Bank did not discriminate against them. On the other hand, there were no Catholic applicants to the Bank. This was largely a reflection of demography. It has been estimated that by 1780 only 1 per cent of the British population was Catholic (O'Gorman Reference O'gorman1997, p. 312). But the Bank of England had also, on the discovery of a ‘Papist’ employee in 1746, introduced rules that prevented the employment of Catholics. There is no sign that the gentleman in question, Thomas Macdonnell, was anything other than an exemplary employee but with the Jacobite rebellions fresh in their minds, the Directors at the time were clearly not taking any chances. Catholics subsequently were not considered for posts within the Bank until after the Catholic Emancipation Bill of 1829 (Acres Reference Acres1931, p. 227).

Table 3. Religion of applicants, 1800–15

Source: BEA, M5/406–8, passim.

Men were also asked about clubs to which they might belong. This line of questioning probably emerged in the aftermath of the French Revolution and particularly with the rise to prominence of radical societies, such as the London Corresponding Society, founded in 1792. Unsurprisingly, no men in the sample preserved in the examinations books admitted belonging to any political clubs although a couple did note membership of friendly societies and Samuel Field confessed to being a member of a card club that met once a fortnight in the Furnival Inn.Footnote 17

Indebtedness was a different matter. Men who were at the time of the interview in business for themselves were quizzed carefully about their credit-worthiness and the stability of the enterprise. Thus Charles Russell revealed that he was making his living as a bookseller and was married to a woman who had two children from a former marriage. He noted that, if offered the job at the Bank, his wife and her son would carry on that business. Russell also revealed that he had around £400 in demands against him but book debts sufficient to meet those demands and a £60 per annum annuity from his wife. His account satisfied the committee.Footnote 18 A number of men admitted to being discharged bankrupts. William Smith Oakley had been in the wool business with his father but they had been made bankrupt. Oakley could produce his certificate of discharge.Footnote 19 James Jackson had been a linen draper but had become bankrupt with debts of £175. He had managed to pay his creditors 15 shillings in the pound.Footnote 20 In considering the applications of discharged bankrupts, the Bank was following English law, which granted bankrupts who fully cooperated with the Commission of Bankruptcy a full discharge of their debts and a small stipend, thus allowing them to rebuild their lives (Kadens Reference Kadens2010, p. 1261).

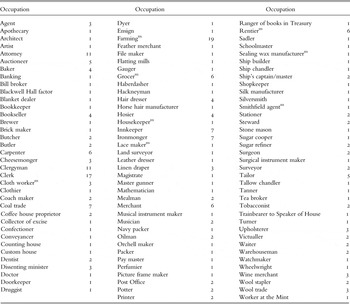

It is difficult to be precise about the social status of candidates. The nineteenth-century view was that occupations recruited chiefly from ‘the children of those already employed in it’ (J. S. Mill quoted in Leunig, Minns and Wallis Reference Leunig, Minns and Wallis2011, p. 413). Studies focusing on earlier periods have drawn similar conclusions. They have tended to argue that ‘options were restricted by parents’ resources and their networks of acquaintance' (Thomas Reference Thomas2009, p. 16) and that a clear tendency towards ‘occupational inheritance’ existed (Mitch Reference Mitch, Floud and Johnson2004, p. 337). The fact that so many sons of existing clerks sought work at the Bank would also suggest that some vestige of a system of ‘occupational caste’ was in operation. Nonetheless, the occupations of the parents of the applicants with no familial connection to the Bank show significant diversity. The interviewing committees recorded parental occupations in 260 cases, mostly relating to fathers' occupations, but mothers' occupations were noted if the father was already deceased. Among these individuals there were very few clerks. As Table 4 shows, the remaining parents appear to have been drawn from the higher artisanal classes and from the middling sorts but were engaged in varied occupations demonstrating that occupational caste held relatively little sway in the clerical profession. This also points towards conclusions reached by more recent studies of apprenticeships showing that labour markets in skilled employment were not heavily constrained by social barriers (Leunig, Minns and Wallis Reference Leunig, Minns and Wallis2011, p. 436).

Table 4. Occupations/social status of fathers and mothers of applicants grouped by sector (m =includes mother's occupation)

Source: BEA, M5/406–8, passim.

Because candidates were drawn from a range of backgrounds, sons of serving clerks excepted, it is pertinent to ask what methods men used to get noticed by their nominating directors. Although little specific evidence can be found, some routes were obvious and it is possible to speculate about others. Naturally some directors nominated their own servants and clerks to positions in the Bank. Such was the case for Thomas Wickstead, nominated by the director Mr Whitmore, who also gave Wickstead a ‘very good character’.Footnote 21 As was typical in recruitment to other similar organisations, some candidates would have been introduced to directors through third parties. Friends, business partners or acquaintances might have recommended either their own employees or perhaps their sons or some other family member for preferment (Makepeace Reference Makepeace2010, pp. 45–7). Churches and non-conformist meeting houses might have been another locus for making connections. There is also some evidence of networks of patronage. Thus, of the 638 applicants with no familial connection to the Bank, 16 had some connection to Reading. The Bank's records also reveal a director, Edward Simeon, with strong connections to Reading. It seems likely then that it was known in the area that Simeon was willing to recommend local young men for positions.

Although, potential clerks or their fathers did not necessarily move in the same social circles as the Bank's directors, another route to contact might have been through an existing job. Men working in counting houses, banks or one of the government offices were likely to come into contact with one or more of the Bank's directors or their friends. But booksellers, haberdashers, clerks to wine merchants or men working in one of the City's coffee houses would also have encountered a wide variety of people through their work and perhaps been noticed by or indeed found the courage to talk their way into a better position. The latter strategy, of course, was a risky one since it encompassed both the risk of rejection by the Bank and alienation of a current employer. Such was almost the fate of William Thetford, who applied to the Bank in 1804. Thetford was dismissed by his previous employer ‘on account of his application to be taken into the Bank’.Footnote 22 Fortunately the story ended happily, William and his brother John were both offered positions at the Bank.

The range of middling sort and artisanal backgrounds from which applicants to the Bank were drawn points clearly to expansion of the clerical class at this time. This was a necessary consequence of the need to meet the demands of the fiscal-military state. For applicants this undoubtedly brought the advantage of somewhat lower entry barriers to work at the Bank. For the Bank itself, this created more of a problem because, as the following sections will demonstrate, there was a clear gap between the skills it required and the skills available amongst the existing workforce.

III

Modern studies emphasise that formal education is an important factor in the development of human capital (Becker Reference Becker1984). Yet, the quality of school education available at the end of the eighteenth and start of the nineteenth century was often inadequate to the task of instilling the skills needed for clerical work. Traditional grammar schools still concentrated on offering a classical education. A more ‘modern’ education might have included English and mathematics perhaps with some attention to the humanities, foreign languages and those other socially valuable skills of drawing and dancing. Commercial schools placed more emphasis on the skills that were required of Bank clerks: being able to write a good hand and basic maths and bookkeeping. Yet, in all areas of education, abuses and neglect were common and provision at secondary and higher levels was generally poor (Langford Reference Langford1998, pp. 79–88; Mitch Reference Mitch, Floud and Johnson2004, pp. 346–7). In consequence, only a very small proportion of the population would have had more than a few years' formal schooling (Wallis Reference Wallis, Floud, Humphries and Johnson2014, p. 201). Nonetheless, most applicants to the Bank appear to have had a school education. Only one man from the sample confessed to a university education. Ames Simon Cottle received his bachelor's degree from Magdalen College, Cambridge. The committee recorded that his handwriting was ‘not fine’.Footnote 23 Other candidates mentioned specific schools such as the Blue Coat schools, Christ's Hospital and Charterhouse. Thomas John Jones had been educated at the Naval Academy in Chelsea.Footnote 24 Scott Francis, aged 19, had been at a college in Rheins in Champagne for five years but had been unemployed since his return to England a year previously.Footnote 25 Henry Wyburd was the only candidate who mentioned being educated by a private tutor, undoubtedly a more expensive option for Wyburd's parents or guardians (Langford Reference Langford1998, p. 87) but, in this case, money relatively well spent. Wyburd was acknowledged to be quick at figures and have the potential to improve his handwriting.Footnote 26 John Dance had been educated by his father, who did not do such a good job, Dance was noted as only having ‘tolerable’ handwriting and being ‘middling’ at accounts.Footnote 27

The questionable value of formal education during this period suggests that length and level of schooling was not, and could not be used as, a reliable indicator of attainment and ability by the Bank's interviewing committees. It was perhaps for this reason that, as we shall see, such a great emphasis was placed on the testing of applicants. It was perhaps also a reason why so few men applying for a position at the Bank of England were embarking on their first position since leaving school. Indeed, given that the average age of candidates was around 21 among men with no familial connections to the Bank and around 18 among sons of clerks, this suggests prior work experience of between three and seven years, assuming a school leaving age of around 14 or 15.

Although evidence is not plentiful, the Bank of England does appear to have been unusual in preferring to recruit men with work experience. Bowen's study of the East India Company, for example, suggests some candidates for employment were often just 15 or 16 years of age (Bowen Reference Bowen2006, p. 141). Sayers also emphasised the employment of school leavers at Lloyds Bank (Sayers Reference Sayers1957, p. 68). Checkland noted the use of an apprenticeship system in the Scottish banks from the early nineteenth century, with the National Bank at least stipulating that its clerks should be no younger than 15 but no older than 20 years of age (Checkland Reference Checkland1975, p. 393). In other public banking systems too, younger men were preferred. The starting point for workers in the public banks of Naples during the eighteenth century suggests a maximum age of 20, clearly indicating a desire to train young men in the ways of the bank (Avallone Reference Avallone1999, p. 120). This system was also characteristic of more recent banking recruitment even in environments, such as Australia, where suitable labour was in very short supply (Seltzer and Simons Reference Seltzer and Simons2001, p. 202).

Although the diversity in parental occupations noted above is also reflected in the occupations of candidates, we do find a large concentration of applicants from other banking houses or what might be termed complementary occupations. As Table 5 shows, around 50 per cent of applicants were working as clerks or bookkeepers, in counting houses, other banking houses or in the law, insurance or education or government offices such as the Customs House or the Excise Office. These occupations offered the potential for the acquisition of transferable skills that might have been an advantage for those applying to the Bank, but one man had gained skills that were clearly a concern to the committee. Charles Marcuard had been employed for five years as an engraver, thus having acquired one of the key skills of a banknote forger. Marcuard's application was referred to the Court of Directors before being accepted.Footnote 28

Table 5. Applicant's occupation at time of interview

Source: BEA, M5/406–8, passim.

The Bank did also draw in a large number of applicants with apparently no relevant previous work experience. Richard Hughes, for example, was a landscape painter at the time of his application.Footnote 29 James Allanson from Knaresborough, north Yorkshire, was the son of a farmer and was noted to be living and working with Mr Tucker and Co., plate manufacturers.Footnote 30 John Chappell had been brought up to be a stationer with his father and apparently had never been away from his family.Footnote 31 Hughes, Allanson and Chappell were all regarded as having promising qualities. However, John Carman, an umbrella maker, was found to have only ‘indifferent’ handwriting and his application was rejected.Footnote 32

Men with no relevant work experience sometimes received training or moved into jobs that would allow them to pick up banking-related skills before applying to the Bank. Thus, Andrew Fenoulhet had been a hatter and hosier but had received three months training in accounts and writing and declared his intention to continue that training in the evenings after his working day was finished.Footnote 33 Robert Dodge Barton had been a tallow chandler but had more recently become a clerk in his brother's wine merchants. He was judged to be able to write well but was not ‘ready’ with accounts.Footnote 34 Charles Parry, a hatter, was rejected at his first attempt to enter the Bank in June 1801 and subsequently sought employment writing out and settling accounts. By his second interview, his handwriting was improved.Footnote 35 Other men tried to emphasise relevant transferable skills, such as Thomas Reynolds who, although employed as a haberdasher, claimed to spend much of his time ‘copying out manuscripts’.Footnote 36

Adding to the list of those whose previous work experience was not always useful to the Bank were a significant number of men who were either unemployed or seemingly underemployed at the time of their application. There is no evidence that the Bank disadvantaged unemployed applicants. Indeed, around 10 per cent of applicants claimed to be unemployed at the time of interview. Such was the case for George Baldwin, aged 28, who had been out of work for around six months at the time of his application.Footnote 37 Samuel Rickards, aged 29, had been two years in town and was still not in employment.Footnote 38

Some of the interviews with unemployed men also point to the precariousness of business life during the early nineteenth century. Hence Charles Castleman had been apprenticed to a wine merchant whose business had failed. Castleman had been unable to find full employment since and was currently occupied in keeping the books for his uncle, a bricklayer.Footnote 39 Charles was not the only applicant to hint at underemployment. Around 5 per cent of applicants claimed to have been employed in keeping their father's or brother's books or assisting in a relative's business in some other way. Others were just noted to have been with their father since leaving school. Of course, we cannot be clear about what these men were doing; it may be that they were indeed fully employed in the family business. Yet, if so, and if operating as a valuable member of a family business, it seems unlikely that they would be seeking alternative employment.

Early nineteenth-century unemployment rates are notoriously difficult to measure and what calculations have been done relate to labouring and agricultural employment (Feinstein Reference Feinstein1998, p. 646; Voth Reference Voth2001, p. 1078). These calculations, however, suggest an unemployment rate of around 5 per cent during the early years of the nineteenth century and prior to the mass demobilisation that took place at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. This means that the Bank's records indicate unemployment among the higher artisanal occupations and middling sorts was much higher than the norm. Of course, the evidence is hardly conclusive and it might point to no more than a shifting pattern of working for the middling sorts, away from predominant self-employment or semi-employment in a family business towards full-time employment in the service of another. There is insufficient evidence here to speculate further but one thing is clear: high unemployment rates did not automatically bring the Bank a cheap labour force of skilled workers.

IV

The result of the Bank's tests confirm that the skills it required were possessed by relatively few. As noted above, the Bank imposed three tests on candidates: a test of their handwriting, a test of their ability with accounts and a test of their ability to ‘tell’ money. The specifics of the tests have not been preserved but we can speculate that good penmanship required a neat legible hand, the ability to write without leaving blots on the paper, and the ability to copy without error. Indeed, errors were to be avoided at all costs because of the potential association of the erasure of errors with fraud (Jeacle Reference Jeacle2010, p. 315). Speed was also important and the committees often praised expeditious hands. With regard to accounts, candidates had to be competent in simple mathematics and to understand double-entry bookkeeping. The Bank's test, however, appears to have involved the addition of columns of figures. In the handling of money, candidates had to be able to recognise numerous different forms of specie and notes and understand their value. Thus the test of ability with money appears to have consisted of a requirement to compute a number of ‘parcels’ of cash and it was measured by speed, in number of minutes taken, and accuracy by number of parcels computed inaccurately.

The handwriting and accounting tests were measured only by speed, in number of minutes taken to complete the tests, and the committees recorded a subjective comment on accuracy or quality of the work. The test results reveal considerable variation in the ability of candidates. Among candidates with no familial connection to the Bank, time taken to complete the handwriting test ranged from 10 to 55 minutes and time taken to complete the addition test ranged from three to 50 minutes. With regard to the test of telling money, times taken ranged from 15 to 65 minutes and only 3.37 per cent of candidates (20 out of the 594 tests that can be traced) managed to complete the tests without error. The sons of clerks who, it might be argued, with advice from their fathers had the opportunity to make a more effective preparation for the tests, did little better. Amongst the sons, time taken to complete the handwriting test ranged from 15 to 55 minutes and to complete the addition test from two to 35 minutes. The time taken to complete the tests of telling money ranged between 20 and 60 minutes and only two men, 2.2 per cent of the total number of sons of clerks, managed to calculate the parcels without error.

The test of telling money offers a fascinating insight into the difficulties of dealing with the monetary environment of the late eighteenth century which encompassed not just current English coin but some much older and a great deal of foreign coin as well as a wide variety of banknotes. Even accounting for this and the nervousness of candidates, the very low percentage of men who were able to pass the test without error is significant. Moreover, as Figure 1 shows, the results were not skewed by a few very poor performances, in fact performances were highly variable and, in particular, show that the ideal of the ‘fast and accurate’ cashier was not available to the Bank at point of entry. Indeed, a closer examination of those men who completed the test without making any errors shows that the average time taken to complete the test was 30.23 minutes, indicating that steadiness rather than expedition was the key to accuracy for those men. They were equally steady in their other tests. The average time taken by them to complete the writing test was 24.76 minutes and the average time taken to complete the addition test was 9.23 minutes. Samuel Field was quick, completing the writing test in 15 minutes and the addition test in five but was judged by the committee to be ‘not ready’ with regard to addition, a phrase that seemed to indicate inaccuracy.Footnote 40 Only eight men out of this group received unequivocally positive remarks from the committees.

Figure 1. Results of tests of telling money

Nonetheless, if we regard the 22 men who managed to complete the tests with money without error as being amongst the most highly skilled that the Bank could acquire, it is possible to draw some conclusions about how these skills were acquired. It is notable, for example, that the average age amongst this group was 23 with over 40 per cent of the group being over the age of 25, thus suggesting that long work experience was one of the keys to skill acquisition. Equally, the majority of this group were working at the time of interview in banking or similar occupations. Only six out of the 21 members of this group whose previous occupation was recorded were engaged in seemingly non-compatible work, this included a farmer, a baker, and oyster netter, the superintendent at St John's chapel and 17-year-old John William Mackintosh who was still in school.

As shown in Table 6, extending such assumptions to the entire cohort of applicants tends to support the finding that performance improved with the age, and arguably the experience, of the candidate. There were nonetheless no very significant differences in performance. Table 6 also confirms that, while the sons of former and existing clerks in the 17–20 age bracket performed slightly better at addition and telling money, the Bank in fact derived no particular advantage from employing men with a familial connection to the Bank. The clerical class, therefore, did not provide a ready-made next generation of workers.

Table 6. Performance in Bank's tests measured by age of applicants

Source: BEA, M2/116, Drawing Office, candidates' examination book; M2/121, Tellers' Office, candidates' examination book; M5/681, Secretary's Department: candidates for election, 1799–1840, passim.

Table 7 shows performance in the Bank's tests grouped by the previous work experience of the applicants. Occupations were coded as providing or not providing relevant, office-based, skills, such as work in banking, in counting houses, as clerks, in insurance, government offices and schooling. Men were coded as unemployed or underemployed if they admitted to being out of work at the time of interview, said that they were working intermittently or just described themselves as being ‘with their father’. The results displayed in Table 7 show that, while once again the differences were not great, men with previous relevant work experience could outperform those who were unemployed or in employed in other sectors of the economy in writing and in addition. The test of telling money revealed somewhat different results: men working in non-relevant occupations did slightly better than those in office-based work. Here we may assume that men working in the retail sector or small-scale manufacturing might have come into contact with coin and notes more regularly than men undertaking some office-based roles. Again, though, the dominant finding is that there was no significant advantage to the Bank in seeking out men with office-based work experience.

Table 7. Performance in Bank's tests measured by previous experience of applicants

Source: BEA, M2/116; M2/121; M5/681, passim.

The results of the Bank's tests confirm the white-collar skills shortage which has been observed in the work of other scholars. This was a shortage that apparently persisted into the middle of the nineteenth century (Boot Reference Boot1991, p. 648; Sayers Reference Sayers1957 p. 63). Especially during the period from 1800 to 1815 this presented a particular problem for the Bank. As we have noted its business was expanding rapidly and thus it had to recruit large numbers of clerks quickly. It, therefore, had to rely on strategies other than the location of skilled recruits to preserve its business.

V

The foregoing discussion has established that the Bank's ability to cope with the strains created by the Napoleonic Wars did not originate in the skills of its entry-level clerks. Arguably, therefore, we must consider how the Bank set about transforming a set of applicants, many of whom had no clear natural aptitude with accounts or money, into an effective workforce. Although no details of the Bank's training systems can be traced, it is possible to speculate on several factors that might have allowed the institution effectively to manage its workforce: the creation of an internal labour market, the establishment of systems to monitor staff and encourage diligence and the specialisation of the Bank's functions.

An internal labour market is characterised by limited points of entry into employment, internal promotion to fill senior positions, career longevity and transparent pay practices (Seltzer Reference Seltzer2004). The Bank of England displayed all these characteristics: throughout its early history it recruited only at entry level and trained men on the job, apparently, as and when needs required. Senior men had all worked their way up through the ranks and were paid based on merit and seniority. Arguably an internal labour market offered the Bank several advantages in dealing with an entry-level workforce with questionable skills. First, it meant the creation of a middle and senior rank of men with long experience of the Bank's procedures and processes who were ready and available to supervise and train newcomers. Although somewhat anecdotal, the career trajectory of Mr Walsh of the 3 per cent Consols office reported to a Committee of Inspection in 1783 is instructive. He told the Committee:

That he had been 12 years in the Bank, & for the last 4 years one of the 3 Chief Clerks of this Office, being appointed Assistant to Mr Miller & Mr Vickery. That when he first came into the Bank, he was placed in the department of the Chief Cashier where he went through the Offices of OutTeller & InTeller, & was some time at one of the Cash books & assisted in the Bullion Office at the time of taking in the deficient Gold Coin; he was afterwards removed into the Accountants Office, which he went through; & from thence to the 3 P Ct Consols, where he has seen every part of the business before he was appointed one of the Chief Clerks.Footnote 41

Such men acquired a deep knowledge and skill set that they would have been able to pass on to more junior members of staff.

Next, the creation of an internal labour market meant that the Bank could avoid a rising premium for buying in skills throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It could keep its junior members of staff relatively low-waged and reward the acquisition of skills and seniority. Finally, the reward of skill acquisition and seniority, rather than just ability, is now regarded as an important factor in maintaining the morale of employees and ensuring effort over the lifetime of a career (Seltzer and Simons Reference Seltzer and Simons2001, p. 197). The Bank did indeed tend to retain its workers, many of whom had very long careers within the institution. Thus, the Bank reaped the benefits of its investment in its clerks. For the clerks, on the other hand, rewards could be slow to materialise implying that that the Bank tended to attract workers willing to take a long-term view on the returns for their labour.

The second factor that allowed the Bank to operate with underskilled entry-level workers was systems of monitoring and reward and punishment to encourage loyalty and diligence. The development of a level of intermediate management has been noted above. While the chief accountant and chief cashier, answering directly to the Court of Directors, had overall responsibility for work at the Bank, each office appointed a senior man and often supervisors who were responsible for the day-to-day management of the offices. In addition, periodically from the 1780s, the Bank appointed its directors to Committees of Inspection whose role was to examine the operation of the Bank and the fitness of its staff. From 1800 three permanent committees were established having oversight of the Stock Offices, the Printing and Bank Notes Offices and the Cash Offices respectively. Although the effectiveness of these modes of oversight cannot be measured, it is clear that the committees operated to expose the Bank's systems and its staff to regular scrutiny and that swift response to the discovery of serious failings was expected.

At an individual level, the Bank operated systems of rewards and punishment for its staff. Clerks could be made financially responsible for errors that led to losses for the Bank. Each clerk was also expected to provide the Bank with personal security starting at £500 for junior clerks and rising to a maximum of £5,000 depending on responsibility. The Bank was diligent both in maintaining up-to-date records for guarantors and pursuing compensation in the event of significant losses resulting from errors or dishonesty (Acres Reference Acres1931, i, p. 133). On the other hand, bonuses were paid to reward prompt and regular attendance, although pay was withheld to punish absence. In some offices ‘overtime’ was paid on a piecework basis. Thus in the Discount Office clerks were allowed 10s 6d for every additional 350 bills posted after their expected daily work was completed (Acres Reference Acres1931, ii, p. 359). Efficient working was, therefore, encouraged by financial reward.

The third factor that allowed the Bank to compensate for the lack of skills available at entry level was the specialisation of its functions. As in the Discount Office, most men working at the Bank at junior levels spent their days engaged in mundane and repetitive work designed to be coordinated with other members of individual offices. While the language of skills has been used throughout the discussion so far, in fact, by most definitions, work at the Bank was not particularly skilled. In this respect, Green's articulation of the complexities of defining skilled work in the modern economy is illuminating. It indicates that skill should encompass the negotiation of significant complexity or the application of thought, discernment and independent decision-making (Green Reference Green2013, pp. 9–26). Such functions would have been required of relatively few roles at the early nineteenth-century Bank of England. Indeed, arguably what can be observed is a process of deskilling, such as apparently occurred during industrialisation. In manufacturing, dividing processes into specialised steps meant considerably less investment in skill acquisition (Berg Reference Berg and Joyce1987; Mitch Reference Mitch, Floud and Johnson2004, p. 347). Perhaps the same was true of work in the nineteenth-century Bank of England.

VI

This study of the labour force available to the Bank of England at the start of the nineteenth century shows that there was a clear over-supply of labour but no clerical class from which the Bank could draw its candidates for employment and certainly no over-supply of skills. This finding is consistent with broader studies of the labour force in industrialising Britain, which although disagreeing about the size of the gap, still indicates a gap which points to underinvestment in human capital (Mitch Reference Mitch, Floud and Johnson2004, pp. 357–50). This serious mismatch between the needs of the employer and the skills of the potential workforce meant that there was a need for diligence in the training and monitoring of new staff and a significant investment in human capital made by the Bank itself. However, it is probable that it was not an investment in broad training but rather a process of deskilling through the specialisation of the Bank's functions that allowed it to operate with relatively few workers who might have been defined as truly skilled.