Introduction

Knowledge of the past was important in the formation of a leading official or prospective ruler in the Mughal empire. As ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq Dihlavī, an influential scholar and one-time courtier, wrote in the early seventeenth century:

All created beings need reason, and reason needs experience, and for experiences a long period is necessary and a long life and free time and ease of mind. So, when the sages of the world saw that the length of the transitory life does not suffice for that, they devised a remedy and made a plan to constrain this loss and compensate for this privation. They recorded in books and chronicles the news of the rulers and the circumstances of the nobles and ministers and the words of the scholars and philosophers. And they put down in writing the stories and annals of those who lived in the past for the benefit of those to come [and] to rouse the heedless ones … That which is not acquired concerning the properties of the world and the properties of the time and their people through experiences and choices over the length of a long life and after undertaking long and distant journeys and associating with different sorts of people and measuring their actions and works—in a short time [all this] is acquired [through the aforesaid writings]. The wise man must not be deprived of the share of lessons and expertise, and must balance it up for himself and his own circumstances.Footnote 1

Thus history as distilled collective experience framed the expectations of contemporary Mughal decision-makers. It helped them discern the present state of affairs and the possible consequences of current and future policies.Footnote 2 It helped them deal with the challenges they faced as the empire's ruling elites and to improve its sovereign governance in accord with prevailing ideals.Footnote 3 Therefore, to comprehend the actions of Mughal decision-makers we must take into account their understanding of history. Rulers and regimes from the distant past loom large in this. But so does the past of their own time and place, of their own dynasty and empire. The focus of this article is on the latter. It gives an analysis of histories composed by Mughal officials at the moment of their empire's greatest territorial reach—around 1700, when Mughal paramountcy knew no peer nor threat—in order to reconstruct orthodox interpretations of the Mughal past dispersed among the ruling elites. In so doing, we recapture their political sociology of empire as they conceived it. This has not been done before.

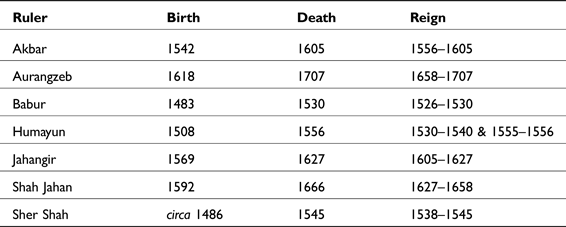

There exists a wealth of scholarship on Mughal and, more generally, Indo-Persian historiography.Footnote 4 It was one of the earliest subjects to be studied by Western Orientalists, and interest in it has been sustained ever since. There are, however, major gaps in what has been covered by modern scholars. These gaps are not accidental nor are they due merely to a dearth of specialists. Rather, they result from choices shaped by the intellectual approaches and goals which have prevailed until recently—and, in several respects, still prevail.Footnote 5 Most pertinently for this article, the choices mean that histories composed in Akbar's reign (1556–1605) and in the period of the Company Raj (circa 1750–1850) have been stressed at the expense of those composed over the long stretch of time in-between. The subsequent gaps in the subject's coverage have allowed widespread views on the development of historiography in the Mughal empire and its ‘successor’ regimes to persist unquestioned and unsubstantiated. On a closer look, many of these are vested in a combination of ‘unwarranted ethnocentrisms, anachronisms, essentialisations and path dependencies’.Footnote 6

This article seeks to remedy the situation in a particular way. It analyses histories composed at a moment in the trajectory of the Mughal empire—a moment of sovereign hegemony of unprecedented scope, straddling the end of the seventeenth century and the turn of the eighteenth—which was recognized as highly significant then, and in retrospect. These histories, which (as discussed below) have hitherto never been systematically examined, were authored by a spectrum of current or former Mughal officials at that very moment. Though the histories are of different types, all of them give an account of the Mughal past from its origins up to at least the start of Aurangzeb's reign (1658–1707). They have been analysed here to determine their authors’ interpretations of the Mughal past. These interpretations are then juxtaposed with mainstream scholarly views today on Mughal historiography between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and on the cognitive framework within which Mughal officials operated in around 1700.

The foregoing analysis is facilitated by an approach that stands apart from those normally adopted by others who have worked on the subject. Scholars to date have tended to analyse texts with historical content, be it within the same genre or across genres, by focusing on either their philological or, more recently, their discursive dimensions.Footnote 7 My approach, in contrast, draws upon the traditions of historical sociology and conceptual history to focus instead on their material and cognitive dimensions.Footnote 8 At the core of this approach lies a heuristic model that enables constants and contingencies to be distinguished in a systematic manner. The constants are the near-universal conditions and problems characteristic of known complex polities.Footnote 9 The contingencies are the structures and solutions embedded in specific contexts. In this model, attention is directed, on the one hand, to the structures out of which the historically consequential conditions were fashioned and, on the other, the solutions which addressed the historically consequential problems.Footnote 10 Deploying this model to analyse the Mughal histories composed around 1700 gives rise to the detailed findings in the article's central sections. These findings in aggregate provide us with a purchase on how Mughal elites of the time conceptualized and related to their empire as a functioning entity. More specifically, they elucidate the political sociology that contemporary high officials held in common. Some aspects of this political sociology clash with the views pervading the modern scholarly mainstream; others complement them.

A large number of works with historical content were written by and for the Mughal elites, many of which survive in multiple copies. In volume, sources, content, range, style, and authorship, they mark a significant advance on what had previously been seen in the Indo-Persian or Persianate world.Footnote 11 For the purposes of this article, the works of interest are those composed around 1700, during the high-water mark of the empire's territorial reach, which minimally cover most of the Mughal past down to their date of completion. Only four meet these requirements:Footnote 12 Mirʾāt-i jahān-numā by Muḥammad Baqāʾ (1627–1683), Lubb al-tawārīkh by Vindrāvandās (d. after 1690), Khulāṣat al-tawārīkh by Sujān Rāi (d. after 1696), and Muntakhab al-tawārīkh by Jagjīvāndās (d. after 1709). The historical portions of these works, none of which were officially commissioned or sponsored, are structured by dynasty and reign, and stress political, military, and administrative affairs, as is typical of their genres. More specifically:

I. Mirʾāt-i jahān-numā (hereafter, ‘Mj’) is a general compendium of world history, with a substantial biographical section, whose account of the Mughal past goes up to the tenth year of Aurangzeb's reign (1668). The reigns of Babur, Humayun, and Akbar are presented as a series of self-contained topics, while the remainder takes the form of a yearly chronicle. Its author, Muḥammad Baqāʾ,Footnote 13 occupied the positions of bakhshī (paymaster) and vāqiʿa-nigār (daily chronicler) at Aurangzeb's court. Left unfinished at his death, the work survives in two recensions completed posthumously, one in 1684 by his nephew and the other in 1699 by his brother.Footnote 14

II. Lubb al-tawārīkh (hereafter, ‘Lt’) is a general history of India through to 1689–90. Narrated as a series of loosely tied topics, its author, Vindrāvandās,Footnote 15 who occupied the position of dīvān (high-level revenue or finance official), completed the work in 1694–95.Footnote 16

III. Khulāṣat al-tawārīkh (hereafter, ‘Kt’) is a well-known general history of India from the earliest times to the conflict surrounding Aurangzeb's succession in the late 1650s, and includes a geographical description of India. The historical portion is narrated as an integrated series of distinct episodes. Its author, Sujān Rāi Bhandārī,Footnote 17 was a munshī (secretary) in the employment of high officials, and completed the work in 1695–96.Footnote 18

IV. Muntakhab al-tawārīkh (hereafter, ‘Mt’) is a short general history of India up to the immediate aftermath of Bahādur Shāh's accession in 1707, and incorporates a statistical account of the empire ordered by Bahādur Shāh. Drawing heavily on Lubb al-tawārīkh for the earlier sections, it is narrated as a series of loosely tied topics. The author, Jagjīvāndās,Footnote 19 was a harkārah (official concerned with intelligence and communication) and completed the work in 1708–09.Footnote 20

There exist important differences between these four histories. Several are a direct function of their overall length, which varies considerably and is reflected in the number of individuals, events, and themes covered, as well as the amount of detail provided. Other differences, however, seem to result from the predispositions or ideological bearing of the authors themselves. On the face of it, these latter are related to their degree of attachment to Islamic orthodoxy or, alternatively, their openness to religious (and ethnic) plurality. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as the sole Muslim author among the four, Muḥammad Baqāʾ's attitudes tend most towards Islamic orthodoxy. This may be seen in his condemnation of Akbar's purported heresy (and concomitant reluctance to condemn Bairām Khān's monopolization of power while regent during Akbar's minority), his disparagement of Hemu (the low-born Hindu official who went on to become a ruler during the Suri interregnum), and his evident sympathy for Aurangzeb's Sunni character and policies. Of all the authors, Sujān Rāi, a Khatri Hindu, is most explicit about the realities of plurality and partial to its virtues. To wit, he studiously avoids criticism of Sher Shah (who drove the Mughals out of Hindustan), of the Rajputs (even when acting in opposition to the reigning padshah), and of Dārā Shikoh (Aurangzeb's heterodox rival for the throne). These differences notwithstanding, Islam or Hindu-Muslim distinctions are not fundamental to the interpretations of the Mughal past found in the four histories. Furthermore, the differences which do exist pale before the similarities between them. It is the very pervasiveness of these similarities that underpins the reasoning of the sections below. The working rule-of-thumb in those sections is that, unless shown to the contrary (every substantial instance of which is noted in the text), the basic attitudes expressed by one author are presumed to have been shared with the others. By extension, given the wide spectrum of careers, traditions, and communities embodied by the four authors, it is reasonable to take their shared attitudes as commonplace within Mughal officialdom of their time.

Adopting the approach outlined above, the histories have been analysed in order to recover what were considered to be the most acute problems faced by ruling elites in governing the Mughal empire and the manner in which they were addressed in the past. Centre-stage is given to the specific solutions proposed, attempted, or enacted to the problems regarded as especially pressing or significant in defined contexts. The histories make clear that the authors were primarily concerned with loyalty and unity—and their counterparts, disloyalty and disunity.Footnote 21 These concerns lay at the heart of a political sociology of empire. Loyalty in their conception depended on ensuring the acquiescence of elites, officials, and intermediaries to the prevailing dispensation for the continuance of the regime. This highlights the constitution of the body politic and the ideology imbuing it. Unity, on the other hand, pivoted on the capacity of the larger polity to withstand or organically adapt to structural changes or unexpected shocks. This highlights the unifying commonalities within its boundaries, not least confessional and linguistic, and to the forces, often coercive, that pre-empted or defended against fragmentation. In what follows, a section is devoted to each of these in turn, before concluding with a discussion of how contemporary officials understood the developing nature of their empire down to the end of the seventeenth century.

Elite loyalty

Running through all four histories is a concern with the ways in which elite loyalty to the Mughal regime (salṭanat) was secured—or not, as the case may be. The elites in question were the key makers of decisions regarding sovereign governance, and embraced rulers, courtiers, ministers, administrators, and intermediaries. As much attention is paid by the authors to the perceived successes as to the perceived failures in securing elite loyalty. Core to their articulation of these is a calibrated system of generalized exchange. That system buttressed a moral economy within which the careers of Mughal elites were rationalized.Footnote 22

The depiction of this moral economy has elements familiar to modern scholarship.Footnote 23 It was marked by a hierarchy of grades or degrees (manzilat, martabat, darajah), famously institutionalized by the Mughals in the form of enumerated ranks (manṣab).Footnote 24 The existence of these ranks is first noted in the histories, albeit fleetingly, early in Akbar's reign.Footnote 25 As the authors describe it, the underlying system had two mutually generative and reinforcing dimensions, one symbolic, the other material. These dimensions corresponded to each other in an inverted fashion. Inferiors ritualistically humbled themselves before superiors, paying homage or making obeisance in keeping with prevailing norms (ādāb). That went hand-in-hand with inferiors receiving income defined by a numerical zāt which equated to either a cash salary from the treasury or revenue allocated from demarcated territories, and was augmented by awards of money, coined precious metals, or tax exemptions. This exchange was paralleled by another exchange, in which superiors honoured inferiors with titles (khiṭāb) and other conspicuous marks of favour, such as personal robes of honour (khilʿat-i khāṣṣah), jewelled daggers, horses with gilded saddle and harness, or jewelled pen cases. In return, inferiors typically gave superiors valuable gifts (pīshkish, nadhar) and their service in a personal or official capacity at court, or in a military capacity in the provinces specified in terms of number of horsemen (savār, dū-asbah, sih-asbah).Footnote 26

A particular interest is shown in the symbolic dimension of these exchanges. Its significance appears to stem from its function in communicating the relative positions of those concerned within their shared moral economy. By the same token, the symbolic choreography of formal interactions among ruling elites was important enough to be a cause of public deliberation, humiliation, and even armed conflict. For a long time, ‘in keeping with the practice of South and North India (Daccan va Hind)’,Footnote 27 it was customary for recipients of a favour or an order from the ruler to prostate themselves before him (sajdah). One of the first decrees issued by Shah Jahan on coming to the throne in 1628 was, so the histories say, to abolish this practice as only proper for god alone. ‘Kissing the ground’ (zamīn-būs) was proposed as an alternative. Its proponents argued that it maintained ‘the thread of distinction between servant and master’.Footnote 28 Shah Jahan accepted this, though ‘sayyids and scholars and the virtuous and the pious were exempted this practice’, from whom a salutation (salām, taslīm) sufficed.Footnote 29 But that did not bring the matter to an end. ‘Because zamīn-būs is similar to sajdah and sajdah is suited to the court of the creator’,Footnote 30 this too was abolished several years later and in its place Shah Jahan ‘added one salutation to the normal three salutations’.Footnote 31 Protocol is also central to the account of the disgrace of the Mughal pretender Kāmrān. After being defeated in 1551 by his elder brother in the environs of Kabul, Kāmrān reached out for help to Islām Shāh, the Suri ruler in northern India. Islām Shāh sent a welcoming party headed by his son. On Kāmrān's arrival, ‘because of pride or contempt for the prince [Kāmrān], Islām Shāh did not face [him] and he was completely ignored … The prince's honour (ābirū) was violated. In the end, Islām Shāh met the prince with half-hearted respect. This added to the prince's disgrace.’Footnote 32

The symbolic dimension is placed at the root of a conflict which, the authors contend, shaped the very origins of the Mughal empire. Ibrahim Lodi, the last of the Delhi sultans, is quoted as having said: ‘Padshahs are not comparable with any person. Everyone is [their] servant (naukar).’Footnote 33 This view was given force when on Ibrahim's accession in 1517 ‘he changed the formal manner [of interacting with] his kith and kin (khvīsh va qaum)’.Footnote 34 Those who had sat in the presence of his father and grandfather were now ‘forced to stand hands folded before the throne’.Footnote 35 All the histories point out that this innovation offended several of his umarāʾ.Footnote 36 After experiencing further ill-treatment, these umarāʾ turned against Ibrahim and eventually went over to Babur's side, helping him to achieve his long-held desire to conquer Hindustan.Footnote 37 Through recounting events like this, the authors stress the close relationship between elite loyalty and symbolic expressions of deference and respect in formal settings. These symbolic expressions were evidently vested within a well-defined moral economy. If its parameters were transgressed, loyalty to a superior was undermined, considerably heightening the risk of opposition. Such is the significance accorded it in the histories that, as seen with the Lodis and Mughals, transgressions could hasten the end of one dynasty and the start of another.

Structurally, the ideas and practices which crystallized the moral economy served to incorporate—and, importantly, reincorporate—select individuals, organizations, and groups into the imperial regime's body politic. The authors describe this as usually happening in identifiable physical settings, most commonly the ‘court’ (dargāh) or ‘palace’ (daulat-khānah) within a city, fortress, or encampment. Mentioned as well are the physical settings of the more modest ‘house’ (khānah), ‘mansion’ (ḥavīlī), and ‘pavilion’ (khaimah). The daily meetings (maḥfil) and assemblies (majlis) of the ruling elites were held in these settings. They also hosted festivals (jashn) and feasts (bazm) to celebrate special occasions, such as the birth of a potential heir, the anniversary of the current ruler's accession or a major victory in a military campaign. It is during these gatherings that the symbolic and material exchanges noted above took place. In tandem, more ad hoc mechanisms were deployed with a bearing on the loyalty of elites. As a display of singular favour, the ruler might seat an official or intimate immediately beside him.Footnote 38 Conversely, he might banish the official or intimate from his presence to demonstrate his manifest displeasure.Footnote 39 These are of a piece with the idea that proximity to a superior mattered, reflected in the authors’ fulsome accounts of formal gatherings.Footnote 40

Generalized exchanges were routine in nature. They were modulated by a set of tactics which, according to the histories, were of particular value in incorporating new figures into the Mughal elites and in reincorporating those who had turned against the padshah but remained loyal to the regime. Foremost among these was mediation. We occasionally see leading officials playing this role, like the Khān Khānān in Akbar's reign.Footnote 41 However, greatest regard as mediatorsis reserved for members of the ruler's immediate family. Adult sons brought rebels who were unrelated to the Mughal dynasty by blood or marriage back into the fold,Footnote 42 while queen mothers managed to bridge differences within the Mughal ruling family, especially between brothers and between fathers and sons.Footnote 43 Mediation coheres with that facet of sovereign loyalty which was highly personal. That facet is also in evidence in the tactic of summoning to court the children of autonomous elites who wielded considerable influence in their homeland. This tactic is mentioned primarily in dealings with vanquished opponents. In Shah Jahan's reign, the sons of the Turani ruler Nadhar Muḥammad Khān were ordered to court following his submission, and there they willingly stayed.Footnote 44 After his defeat in 1639, Jujhār Singh Bundela's young children were hauled before Shah Jahan, converted to Islam, and reared by ‘trusted people’.Footnote 45 The rationale in both cases is clear: the children were leveraged as guarantors for the continued loyalty of local elites. Moreover, there was an expectation that when grown up they would go on to serve the regime as high officials. This was underpinned by the purposeful intermingling of elite households, and the ties of intimacy thereby fostered. That intermingling is explicit in a third tactic, the use of judicious concubinage and marriages to create affective ties between the lineages of families who furnished the current and future ruling elites of the empire. This is said to have been initiated by Babur,Footnote 46 whose policy his grandson Akbar embraced and elaborated. Leading by example after his accession, Akbar took into his harem the niece of ‘one of the main zamīndārs of Hind’. Later he married the daughter of Raja Bharamal Kachhwaha, ‘the chief raja’ of the empire.Footnote 47 ‘Despite religious differences, [the rajas and Akbar] considered [themselves] exalted by these ties. From both sides, they opened this way.’Footnote 48

These ideas, practices and tactics of incorporation and reincorporation were, the authors suggest, normally enacted in the ruler's court or palace. That suited the metropolitan elites whose service was oriented largely towards the ruler and his regime. This did not hold, however, for other categories of elites, especially autonomous headmen of ethnic communities. These headmen, who often ruled over substantial areas where their kindred resided, were crucial as linchpin figures between the Mughal regime and the general population. The histories give most prominence to Afghans and Rajputs. Bearing Mughal titles, like zamīndār and marzbān, or traditional non-Persian titles, like rānā, rāi, and rājā, the headmen of these communities supplied intermediaries par excellence. Furthermore, by virtue of their Janus-faced character—being rooted in their homelands while simultaneously occupying an official position—the manner in which they related to the regime makes them qualitatively distinct from the more deracinated metropolitan elites. Securing their loyalty is thus treated differently by the authors. These headmen seldom appear in the histories,Footnote 49 perhaps because of the rarity with which they came before the ruler and his highest officials. But that did not make them marginal to the concerns of sovereign decision-makers in the heartlands. Intermediaries were recognized as members of the empire's ruling elites. This explains why the padshah intervened personally to determine succession following the death of a Rajput raja,Footnote 50 and elsewhere left a local ruler in no doubt that if he failed to obey the imperial writ he would be replaced by his brother.Footnote 51

Managing popular opinion through public display is a central motif of sovereignty loyalty. The authors are at pains to show that the Mughals were no exception to this. As they interpret it, the main audience was not the general population but the empire's ruling elites. Several of the forms taken by this display had a cosmic quality to them. Both Akbar and Shah Jahan made well publicized, prearranged pilgrimages to the tomb of Khvāja Muʿīn al-Dīn Chistī in Ajmer.Footnote 52 Other pilgrimages occurred en route while on vacation tours or during military campaigns.Footnote 53 Whether the avowed purpose was to request a special favour or give thanks, pilgrimages were among the most visible acts of personal piety by a ruler. Through them, the ruler came to be associated with the mystique and wisdom of figures often venerated for being ‘connected to the Truth (ḥaqq) and close to the Absolute Living Being (ḥaiy-i muṭlaq)’.Footnote 54 Some of the same associations were evoked through the practice of taking auguries and casting horoscopes.Footnote 55 The authors comment on eminent astronomers and astrologers being engaged to tell the fortune of a newborn heir and his future reign,Footnote 56 and to determine the most auspicious hour for embarking on a military conquestFootnote 57 or for ascending the throne for the first time.Footnote 58 This knowledge was then widely disseminated.

Religious and seasonal festivals carried similar force. The histories document a number of traditional festivals, such as ʿĪd al-Fiṭr and Nowruz, being observed by Mughal elites, often in a lavish, even spectacular, fashion.Footnote 59 Alongside these, new festivals were inaugurated, like the jashn-i vazn by Akbar, which went on to become established fixtures in the courtly calendar.Footnote 60 Public display was also used to highlight the Mughal dynasty being in direct descent from Timur. Anniversaries provided opportune moments for reminding subjects of this fact. ‘In the second year after the victory at Samugarh, [Aurangzeb] celebrated in the manner of the Lord of the Conjuncture, the custom of Amīr Tīmūr. No one had ever celebrated in such a way that the eyes of the high and low glittered with so much splendour.’Footnote 61 These remarks indicate the respect, if not awe, in which Timur was held by the time the histories were composed.Footnote 62 That derived in part from his renown as a great conqueror and in part from him being the culmination of a tradition initiated by Genghis Khan.Footnote 63 Cleaving to this genealogy evidently helped sustain the aura surrounding the current padshah and his family.

As the authors articulate it, generosity was integral to many public displays of Mughal sovereignty. This is no truer than during the celebrations surrounding the accession of a new padshah. From the time of Jahangir, the histories luxuriate in the higher ranks, elevated titles, and valuable gifts received by the princes, great nobles, and imperial bondsmen.Footnote 64 The accessions of Babur and Humayun are, in contrast, glossed in a simpler manner, with generosity mainly taking the form of money grants and territorial assignments.Footnote 65 Generosity was part-and-parcel of success on the battlefield, too. All ranks in the victorious army, not just its leaders, are frequently mentioned as sharing in the spoils from the defeated side. The defeated could also be beneficiaries of a ruler's largesse. If the enemy had fought honourably and reconciliation was a possibility, the authors usually portray the Mughals as magnanimous in victory. Both features figure prominently in the founding of the Mughal regime. After seizing the vanquished Ibrahim Lodi's treasury in Delhi, ‘ten lakh tangah were awarded [by Babur] to each one of the umarāʾ, and all of the soldiers, even the men of Babur's army and other people of the umarāʾ received a reward’.Footnote 66 As for his erstwhile enemy, Babur ‘was gracious towards the mother and children and dependents of Sultan Ibrahim. He granted them their personal possessions and treasury. Furthermore, out of compassion eight lakh tangah were arranged for the queen mother as a suyūrghāl.’Footnote 67

The effect on those privy to such displays of sovereignty were reinforced by their sensory qualities. For rulers to be seen in a particular way was, the authors suggest, of manifest importance. The histories comment on parasols (chatr) being held above rulers.Footnote 68 When travelling, they did so in style, in palanquins or on elephants.Footnote 69 To be heard in a distinctive fashion was also important. Occasionally, their movement in public is described as accompanied by the playing of drums. It would appear that these sights and sounds immediately and palpably signified the presence of the ruling elites. They were a prerogative of the ruler and of the select few with whom he deigned to share these symbols of sovereignty. By stimulating both eyes and ears, he thereby left a sensory imprint on those in his vicinity. This effect is most intensely registered in and around the courts, palaces, and forts of the regime's major cities. But the histories make clear that it was not confined to them. By virtue of the tours and hunts (sair va shikār) regularly undertaken by the Mughal court, the sights and sounds accompanying it were dispersed more widely within the empire. Akbar's Gujarat campaign of the early 1570s to defeat the rebellious mīrzās, who, like him, were descendants of Timur, combined the conquest of a new vilāyat with a trip to see its land and people, and the Arabian Sea (daryā-yi shūr).Footnote 70 In more peaceable times, Jahangir and his entourage visited the same area. They toured Ahmedabad, took in the Arabian Sea, and hunted elephants.Footnote 71 But much more common—and storied—are the trips to Kashmir. After submitting to the Mughal empire in the latter half of Akbar's reign, we learn that the padshahs became habitués of the area, delighting in the area's exquisite gardens, waterways, and flora.Footnote 72

There is no denying that such trips, whether for sightseeing or some other reason, brought the metropolitan Mughal elites to areas of the empire far removed from the traditional heartlands centred on Delhi, Agra, and Lahore. But the prevailing transport and communications technologies, coupled with the natural challenges posed by mountains, deserts, and the rainy season, meant that touring, while noteworthy as an event, was inevitably piecemeal and episodic. It was not—and could not have been—critical to sovereign governance in the Mughal empire at large. In terms of reach and circulation, much more effective in disseminating awareness of the padshah's authority, especially among the ruling elites, were eulogies written by celebrated poets, such as by the ‘king of poets’ (malik al-shuʿarāʾ) Abū al-Faiḍ Faiḍī,Footnote 73 and fataḥ-nāmahs publicizing major victories by Mughal armies.Footnote 74

Much of the authors’ focus is either on the ruler and his environs, or on the heartlands of the Mughal empire. Though these did not always physically coincide, both were characterized by the conspicuous presence of the metropolitan ruling elites. Reflecting their prominence is the interest in the signal policies marking a given ruler's approach to government, variously termed salṭanat, jahāndārī, and jahānbānī. After the fall of the Lodi dynasty, according to the histories, the main task faced by Babur was securing the loyalty of the local elites (aʿyān) of his newly conquered territories in northern India.Footnote 75 We read that he instituted a novel policy well suited to the area's plural character. This was apparently of interest to the Safavid Shah Ṭahmāsp, who described the policy as follows: ‘After Babur had seized the Khilāfat-i Hind from the control of the Afghans, in that foreign country (mulk-i bīgānah) he intermingled with the principal zamīndārs. In [this] time of discord, they became [his] helpers and supporters, and in this manner disorder did not happen in the regime.’Footnote 76 Echoing Babur, his father, once Humayun had recovered the throne he ‘distributed sovereign territories to the jāgīrs of the umarāʾ’.Footnote 77 But what really stood him out as a ruler was being ‘the creator of the regulations governing most of the grades (marātib)’ in the elite hierarchy.Footnote 78

The histories openly acknowledge the debt that later Mughals owed Sher Shah and the Suri interregnum for the effective running of their imperial machinery.Footnote 79 Suri policies were adopted and extended in Akbar's reign. In this, however, the padshah himself is depicted as playing a passive role.Footnote 80 Star billing is given instead to his two leading officials. One was Abū al-Faḍl. ‘The affairs of the empire were managed with his counsel’,Footnote 81 with special praise reserved for his ‘handbook (dastūr al-ʿamal) on matters of salṭanat and jahānbānī, and register of sovereign affairs’.Footnote 82 The other official was Todarmal. His enduring fame stemmed from ‘the rules and regulations in the empire’ established during his tenure as minister.Footnote 83 These were ‘so sound that, although [subsequently] great ministers and great treasurers tried, and continue to try, to destroy those regulations and to invent new laws, they have not and will not manage to do so’.Footnote 84

It would seem that in the domain of government administration there was little left for Jahangir to do. ‘The formula from Akbar's time for administering revenue prevailed in full and revenue officials also maintained the old system.’Footnote 85 The authors locate Jahangir's signature policy elsewhere, in the domain of justice. On coming to the throne, he ‘promised the people to administer justice and do good’.Footnote 86 Evidence shows him endeavouring to keep that promise.Footnote 87 Such was the empire's vaunted prosperity and tranquillity that Shah Jahan was apparently free of any serious pressure to innovate during his reign. He is noted instead for improving the efficacy of inherited policies. This greatly increased the regime's income to more than cover its much higher expenses, while broadening the provision of justice for its subjects.Footnote 88 The authors deem that Aurangzeb's main contribution to routine governance was in relation to the revenue system. He sought to ease the life of his subjects by reducing claims on the imperial treasury from officials and by creating new sources of revenue through, for example, tolls and customs which had hitherto entered the privy purse.Footnote 89 This fiscal initiative is overshadowed, however, by Aurangzeb's purported interest in ‘the divisions of the communities of mankind’.Footnote 90 That interest is reflected in his support for policies that discouraged ‘innovators and apostates and deviants and atheists and polytheists’, and encouraged orthodoxy, particularly in the form of Islam's dīn and the religious sciences.Footnote 91

How regnal policies were apprehended by the authors echoes their perspective on the Mughal past more generally. The past that mattered most to them was anchored in the great cities of northern India. The epithets normally given to these cities in the histories flag their centrality to the empire. Over the period covered, several were recognized as its contemporaneous metropolitan capitals (pāi-takht, pādshāh-nishīn). The apex was invariably occupied by what the authors term Dār al-khilāfah (‘Abode of the Caliphate’). Except for a time when Akbar's Fatehpur Sikri took its place,Footnote 92 this term was almost always reserved for Agra. That changes in the middle of the seventeenth century when the recently constructed Shahjahanabad become the premier imperial capital.Footnote 93 Thereafter, Agra is more commonly given the epithet Mastaqarr al-khilāfah (‘Seat of the Caliphate’) in keeping with its now secondary status.Footnote 94 Through to the end of the histories, Mughal Lahore is frequently denoted by Dār al-salṭanah (‘Abode of the Regime’). This is a testament to the city's importance in the empire's formation and its strategic value geographically. The manner of referring to other cities suggests a more local or particular significance. Those like Kabul and pre-Shajahanabad Delhi, which were primarily known for their political and administrative functions as capitals of the empire's vilāyats, are often designated ḥākim-nishīn (‘seat of the governor’) and termed Dār al-mulk (‘Abode of Dominion’).Footnote 95 Those known for some additional noteworthy quality are given distinctive epithets expressing that quality. So, the authors call Ajmer Dār al-khair (‘Abode of Blessing’) in reference to its spiritual associationsFootnote 96 and, following their conquest by the Mughals in Aurangzeb's reign, Bijapur is denoted Dār al-ẓafar (‘Abode of Victory’) and Hyderabad Dār al-jihād (‘Abode of Jihad’).Footnote 97

Cities were the sites where two particular aspects of the Mughal past are seen with especial clarity. One is control over, and security of, the ruler's immediate family and close intimates. The sensitivities surrounding them are exemplified by the fate of Akbar as a young child, played out in the 1540s between Qandahar and Kabul.Footnote 98 The second aspect was the machinations of the regime's leading figures with direct access to the padshah. They formed cliques (taʿaṣṣub-i maẕhab) around a mix of potential successors, influential officials, and powerful intimates. Though several factional conflicts are detailed,Footnote 99 by far the most intriguing in the eyes of the authors had Nūr Jahān at its heart. After Jahangir married Nūr Jahān, her father and elder brother came to the fore with elevated titles and offices.Footnote 100 In time, ‘all [their] intimates and dependents were allocated ranks and distinguished statuses. Even slaves and eunuchs were honoured with noble (khānī and tarkhānī) titles [and] exalted among the elites.’Footnote 101 This group is portrayed as engrossing the levers of power in the capital as Jahangir withdrew from affairs of state. That eventually brought Nūr Jahān and her supporters into open conflict with other cliques, led by those centred on Shah Jahan and Mahābat Khān, who ultimately combined forces against her.Footnote 102

The forgoing presents the authors’ understanding of how elite loyalty to the regime was addressed by the Mughals. Their working solutions had strengths and weaknesses. Two sets of circumstances recounted in the histories throw both of these into sharp relief. In one set, de jure rulers were incapacitated. This brought to light members of the metropolitan elites responsible for decision-making who would otherwise have remained veiled. According to the histories, incapacitation typically happened in a small number of scenarios. If the ruler was a young child on ascending the throne, and managed to survive the plots against him, the reins of sovereign governance were usually in the hands of a recognized regent or council of regents (pīshkārī). That was the situation during the minority of Akbar, the sole instance of a Mughal padshah being too young to rule in person from the start of his reign. When Humayun died, Akbar's guardian (atālīq, tālīq), Bairām Khān, ensured his charge's succession.Footnote 103 Simultaneously, Bairām Khān took over ‘all the important sovereign matters’Footnote 104 as ‘Khān Khānān of the madār al-mulk and vakīl-i salṭanat’.Footnote 105 There is a degree of equivocation in the authors’ judgement on his regency. Bairām Khān is said to have ‘ill-treated the padshah's bondsmen’,Footnote 106 and ‘by oppressive means many ranks and bountiful jāgīrs were permitted for his attendants’.Footnote 107 Nevertheless, ‘in his devotion [to Akbar] there wasn't any shortcoming or weakness’.Footnote 108

In another scenario, previously active rulers voluntarily withdrew from the business of government in favour of pleasures of one sort or another. The Mughals down to 1700 experienced this merely once. That one occasion, however, left a deep imprint on how their past was remembered and interpreted. Until the middle of Jahangir's reign, ‘the work of salṭanat was fully undertaken by him … [and his] orders fully obeyed’.Footnote 109 But his wine drinking and opium use grew to such proportions that he eventually gave ‘the totality of the matters of governance to the control of [Nūr Jahān] and for himself did not hold on to kingship except the name’.Footnote 110 Nūr Jahān is extolled in the histories for her beauty. An author also praises her for her impressive knowledge of, and talent for, dealing with ‘the affairs of the regime’.Footnote 111 However, that does not seem to have been enough. The consensus view is that her period of de facto rule ended with the imperial polity in a parlous state.Footnote 112

Illness precipitated yet another scenario leading to the ruler's temporary or permanent incapacitation. If this was sudden and unexpected, the histories maintain that instability generally ensued. Of the several instances described,Footnote 113 by far the most consequential was Shah Jahan's illness in the late 1650s. This illness was so severe that he was no longer able to rule and ‘disorder entered the management of government business’.Footnote 114 The authors agree that Dārā Shikoh, who alone among Shah Jahan's adult sons was with him in Delhi at the time, became the effective ruler.Footnote 115 They differ, however, over Dārā's suitability for this position. On one side are those pointing out that Shah Jahan ‘favoured’ DārāFootnote 116 and, even before his incapacitation, was running the empire with Dārā as his ‘crown prince (valī-ʿahd) and deputy (nāib-manāb-i salṭanat)’.Footnote 117 On the other side are those who suggest that, when Shah Jahan fell ill, Dārā, because of his ‘raw desire to rule’,Footnote 118 ‘designated himself the crown prince [and] seized the chance to take into his possession the reins of control of the salṭanat’.Footnote 119 ‘In every matter he acted according to his whims with weak-minded judgement.’Footnote 120 There followed an intense, drawn-out conflict involving all of Shah Jahan's principal sons. For much of it, Shah Jahan remained the titular padshah, even after Aurangzeb's dominance was no longer in doubt. It was only when Aurangzeb finally accepted that Shah Jahan would always prefer Dārā to him that ‘he retired Shah Jahan [and] ascended the throne himself’.Footnote 121 The incapacitation of a ruler, in this and other scenarios, gave the authors an opportunity to reiterate a basic truth: the padshah did not monopolize the loyalty of Mughal elites. Rather, it was oriented to something much larger than him, vested partly in a shared ideology and partly in the empire's centripetal institutions.

Dissenters, rebels, and rivals occupy the largest portion of the histories. This coheres with the notion that they were endemic to the empire. The tensions and crises to which these opponents contributed furnish the second set of circumstances, throwing into sharp relief the strengths and weaknesses of how the Mughals addressed the loyalty problem. Like Aurangzeb during the conflict over succession, the dissenters, rebels, and rivals who fall within the scope of this problem continued to obey the same core principles as the incumbent ruler and his supporters. In that sense, they always remained members of the empire's ruling elites even as they defied, constrained, or even threatened the position of the ruler. So, their opposition was qualified, and reconciliation (istimālat) a conceivable prospect. In one group cluster individuals of sufficient gravitas that their dissent could destabilize the empire from the centre. As narrated, the mainstream elites tried to neuter the threats posed by such individuals by, for example, sending them into exile or appointing them to a challenging post far away from the Mughal heartlands. This is typified by the fate of Bairām Khān. While regent in the late 1550s, Bairām Khān's ‘power and status became supreme. He exceeded the status of the vakālat and the amīr al-umarāʾ, and had total control over all the [imperial] workshops and all [government] business.’Footnote 122 When Akbar abruptly dismissed him as regent and from his other posts in 1560 and forbade him from court, ‘Bairām Khān did not accept the imperial admonishment’.Footnote 123 He left for Panjab ‘with depraved intentions’,Footnote 124 seeking to gain the support of local elites for an uprising against Akbar.Footnote 125 Pursued by Akbar's forces, Bairām Khān was confronted and eventually defeated.Footnote 126 ‘In view of his good service’, Akbar offered him ‘forgiveness and safety’.Footnote 127 Bairām Khān accepted this, came before Akbar, and wept in public. Akbar embraced him, honoured him with a personal robe of honour, seated him as before their breach, fed him from the padshah's plate, awarded him large sums of money, granted parganahs to his dependents, and gave him leave to go on pilgrimage to the Ḥijāz.Footnote 128

Alongside dissidents, there were rebels who tried to break with the empire and carve out independent regimes of their own in territories over which the imperial writ had hitherto run. The authors give numerous accounts of such attempts. Their instigators represented the whole gamut of the ruling elites. They ranged from the brothers, uncles, and sons of the reigning padshah to zamīndārs, vālīs, and ḥākims in distant territories by way of high-ranking metropolitan courtiers and officials. The exemplary case, described in all four histories, is that of Humayun's brothers. They had been assigned extensive territories of the empire as iqṭāʿ. But this failed to suffice; they harboured ambitions of ruling a salṭanat of their own, a cause of endless trouble for Humayun. The shattering blow came during the conflict with Sher Shah. Not only did his brothers fail to come to Humayun's aid, they actively conspired against him in the hope of becoming independent rulers. In the short term, this hope was realized and new, smaller regimes emerged in areas that had previously been claimed by Humayun as padshah.Footnote 129 In the longer term, however, Humayun's brothers were overcome. On this, like every other occasion of a rebellion or dissidence, their leaders were eventually tamed—by being reconciled with, and reincorporated into, the empire—or eliminated—by being killed in battle, executed, imprisoned, exiled, or forced to flee abroad. That taming or elimination buttresses a grand narrative of ongoing territorial conquest and secular expansion through to the end of the seventeenth century. The Mughals enjoyed unprecedented success on this front, to the extent that ‘the [other] great padshahs do not have a tenth of the extent of the mamlakat of [Aurangzeb]’.Footnote 130

Distinct from dissidents and rebels are those who did not just oppose the sitting padshah but also had a credible claim on the Mughal throne. Without exception, these rivals were in the same line of descent as the incumbent ruler, and feature in most of the reigns covered by the histories. As noted above, Humayun's reign was plagued by opposition from his brothers, the sons of Babur. The authors depict them as resolutely driven by a desire to establish their own regimes separate from the Mughal empire (though an instance is recounted of an attempt by Hindal to dethrone Humayun and take his place).Footnote 131 Jahangir faced a threat from his son Khusrau early in his reign which he ruthlessly suppressed.Footnote 132 After his withdrawal from affairs of state, the remainder of Jahangir's reign is characterized as riven by a struggle for power between the camp supporting Shahryār's claim and the camp supporting Shah Jahan's claim.Footnote 133 Shah Jahan, of course, won the ultimate battle for succession. However, some three decades later, when he unexpectedly fell ill and could no longer rule in person, Shah Jahan's adult sons fell to vying with one another, and with Shah Jahan, for control of the regime.Footnote 134 It is said that Aurangzeb, well before the end of his reign, designated his eldest living son as the crown prince. But this was disputed by a younger son, who took up arms against his father in a failed attempt to overthrow him. To pre-empt the kind of difficulties that Aurangzeb had himself experienced earlier in his life, and perhaps even break with the long-standing pattern of rivalry marking the Mughal past, Aurangzeb left his sons a testament (vaṣiyat-nāmah) offering advice on how to govern the empire following his death.Footnote 135

Imperial unity

The problem of loyalty in the Mughal empire overlaps significantly with the problem of unity. Acquiescence is core to both. However, the loyalty in question is that of the ruling elites to the imperial regime (salṭanat), whereas unity is oriented to the general population and its relationship to the body politic. The authors were obviously interested in the matter of elite loyalty. They were equally interested in the ways in which unity was conferred on the imperial polity ruled over by the Mughals (mamālik-i maḥrūsah). This happened through fostering a sense of belonging and at the same time defending against fragmentation. That in turn had a bearing on the capacity of the Mughal world to withstand or organically adapt to structural changes and unexpected shocks.

Unity was predicated on being able to map, at least in the mind's eye, the geography of the Mughal world. The authors had that ability. Marshalled in negation, it helped them distinguish their own imperial polity from other countries and regimes. In so doing, the histories delineate the larger region of which the Mughals were an integral part. This is shown most clearly in the accounts of foreign rulers with whom the padshahs and their elites customarily exchanged gifts, correspondence, and embassies. The importance of polities abroad was such that one of the first acts of Babur after his victory over the Lodis was to send ‘gifts to Samarkand and Khurasan and Kashghar and Iraq and acquaintances and intimates’, and ‘a lot of money to Mecca and Medina and Karbala and Najaf and Mashhad and most of the blessed shrines, [which] made the deserving of these places cheerful’.Footnote 136 By doing so, Babur declared to man and god the arrival of a new dynasty in Hindustan and the end of the Delhi sultans. In passing he also reveals to us the polities deemed worthy of consideration by the Mughals. Collectively these formed a distinct and coherent regional world. Indeed, that region is openly avowed in one of the histories in a section outlining ‘the sultans who are contemporaries of Aurangzeb around the blessed world’.Footnote 137 These sultans ruled over ‘the mamālik of Rūm and Shām and ʿArabistān [,] the mamālik of Iran [,] the mamlakat of Bukhara [,] the vilāyat of Balkh [,] the vilāyat of Kashghar [,] Mecca and Medina [, and] the bilād of Yemen’.Footnote 138

This mapping from without had a counterpart in mapping from within. The histories document two mutually reinforcing perspectives on the latter. One stresses physical distances and travel times. So, in Aurangzeb's reign the Mughal world ‘connected to the ocean to the eastern and western and southern sides, and on the northern side to the passes on the frontiers with Turan and [to] Ghazni on the frontiers with Iran. Both in longitude and latitude it is roughly about one year's travel.’Footnote 139 The other perspective looks at the Mughal world politically. This is done by describing the administrative units—ṣūbah, maḥall, sarkār, parganah—which made up the empire, the revenues (jamaʿ, pīshkish) generated by these units, and their past as independent or autonomous countries.Footnote 140 It is paralleled by descriptions of the conquest of new areas by the Mughals and their capitulation to the mamālik-i maḥrūsah.Footnote 141 Note that, in contrast to some earlier writings, the geographies mapped by these histories do not convey a sense of India or the subcontinent per se.Footnote 142 Rather, their picture of the Mughal world is of an agglomeration of geographically identifiable areas—most prominently, Hindustan, Panjab, Bengal, Gujarat, Kashmir, Kūhistān, Deccan—overlain by an imperial polity.

The governing architecture of this imperial polity extended beyond its northern India metropolitan heartlands of Hindustan to cover territories ruled autonomously. The governing architecture also extended beyond the imperial elites to intrude upon segments of the general population. Bearing witness to its extensive reach are the communal and sovereign duties, rights, and privileges—variously termed nāmūs or tūrah—that, so the authors say, the Mughals recognized, upheld, and protected throughout the empire.Footnote 143 Making this a reality depended on the exercise of Mughal hegemony. And the fount of that hegemony were the metropolitan and provincial capitals, alongside a large array of smaller fortresses (qilʿah), townships (qaṣbah), and redoubts (ḥiṣār).Footnote 144 The mere presence of these settlements was an assertion and reminder of imperial rule over the general population. These were reinforced in a number of ways. The authors note the construction of monuments to Mughal rule in many of these settlements, above all the pleasure gardens, mausoleums, palaces, and mosque complexes from the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan.Footnote 145 Especial praise is lavished on the Shalimar garden near Lahore. ‘It has been heard from travellers of the inhabited quarter of the world that no other garden [compares with it] in beauty and elegance.’Footnote 146 The widespread renown of these monuments undoubtedly served to popularize the ruling dynasty and its regime. But the mechanism considered most effective in bringing the padshah to the attention of the greatest number was the issuance in his name of the khuṭbah va sikkah, ‘the sermon and the coin’. Such was its perceived importance that, as the histories remark over and again, new and would-be rulers made its implementation their priority.Footnote 147

Other ways in which rulers intersected with the general population so as to engender a sense of a shared collective tended to be more episodic in nature. Exemplary justice is one of these. On crossing the river Chanab, local farmers implored Akbar to save them from the oppressive behaviour of a tax collector. ‘As a warning to cruel revenue officials he slit [the tax collector's] throat with a dagger.’Footnote 148 When Jahangir heard that the son of a prominent rāi from Gujarat, who had recently come to court to pay his respects, was forcibly holding a Muslim woman in his home, Jahangir ordered ‘the infidel (kāfir) be punished [in a manner] suited to the crime’. The punishment meted out, which is described in gory detail, was terrible and prolonged.Footnote 149 Alongside instances of exemplary justice, the authors recount steps taken by rulers to institutionalize the administration of justice and render it accessible to the general population. Sher Shah is credited with taking the first steps in the 1540s. ‘In court he treated indigenous and foreign (khvīsh va bīgānah) justice equally and he saw all the people with one regard.’Footnote 150 Jahangir and Shah Jahan continued in that vein by establishing more detailed procedures and demarcating more carefully the jurisdiction of courts on different levels. This allowed for the possibility of appeal to higher courts, all the way up, so it is claimed, to the padshah.Footnote 151

The provision of relief in times of crisis was a second dimension along which the Mughals occasionally took tangible form for the general population. Shah Jahan is lauded for this. In the early 1630s, after his forces had successfully raised the siege of Kabul by the Turani Nadhar Muḥammad Khān, Shah Jahan appointed a judge to oversee the distribution of ‘one lakh rupees from the treasury’ to alleviate the suffering of the city's residents.Footnote 152 At about the same time, the Deccan and Gujarat were struck by a great famine because of drought. Shah Jahan ‘granted seventy lakhs rupees to the sufferers of dearth … and reduced [taxation] by eighty crore dām from the crown lands, which is one-eleventh of the empire's territories’.Footnote 153 Aurangzeb is also mentioned as taking decisive action to deal with dearth.Footnote 154

Crisis relief overlapped with conspicuous bequests, often presented as charity for the needy or deserving. On entering Kabul early in his reign, Jahangir ‘scattered a lot of silver to the spectators’.Footnote 155 Shah Jahan handed out coined silver to the people when he reached Agra for his accession,Footnote 156 and gave gems and silver to the needy and large sums of money to temples (mushkū).Footnote 157 Later in his reign, land and cash were granted to those meriting it via the chief judge (ṣadr).Footnote 158 Aurangzeb took to heart his father's example. When he learnt that in five months out of the year Shah Jahan used to make ‘imperial bequests from the treasury of 79,000 rupees by way of the chief judge to the entitled ones’, ‘Aurangzeb ordered the chief judge and the mutaṣaddīs of household matters to act according to the previous formula for [those] five months and for the other months as well to dispense 10,000 rupees each month to the deserving.’Footnote 159

These acts of exemplary justice, crisis relief, and charity resonate with the onus on ruling elites to facilitate the ease and prosperity of ordinary subjects,Footnote 160 and are detailed with approval in the histories. That onus is also reflected in the infrastructural projects commissioned by several padshahs. Building on the successful initiatives of Sher Shah, for which he is famed,Footnote 161 Akbar, Jahangir, and Aurangzeb are reported to have maintained, improved, and extended the great thoroughfares (shāh-rāh) spanning Hindustan between Bengal and Panjab, and beyond, to Kabul and Kashmir. For the safety and convenience of ‘travellers and wanderers’, fruit trees were planted on both sides of the roads to provide food and shade; at regular intervals wells were dug to make water readily available; tall manārah were erected as milestones; and sarāis were constructed for lodging and protection.Footnote 162 But perhaps the greatest single building project driven by concern for the ‘prosperity of the country and ease of the people’Footnote 163 was Shah Jahan's canal, Shāh-nahr. When completed, it stretched ‘from the place with the Ravi river emerged from Kūhistān’ to Lahore. In crossing Panjab, it irrigated ‘farms and gardens’ and secured water supplies for the area's capital.Footnote 164

The histories make clear that the imperial elites seldom involved themselves directly in the affairs of the general population. This limited their capacity to influence how the unity problem was addressed, and that makes the exceptions worthy of note. The exceptions highlighted turn on the plural nature of the padshah's subjects.Footnote 165 According to the author who tackles the issue most openly, plurality is a fact of social life, brought into being by god and finding expression in ‘a variegated world and colourful mortals [and] various doctrines (mazāhib) and different dispositions (mashārib)’.Footnote 166 Because ‘each sect thinks their tradition divinely ordained and inescapable, plurality is thus a potential source of disunity. ‘They imagine the religion and customs (dīn va aʾīn) of others as mere trifles [and] ascribe divine mercy [solely] to their own condition. And they imagine the disagreeable annoyance of their religion and the execution of their own customs as the assent of [god] … The qualities of the ordinary [adherents] of each group are such that, [since] they do not understand the basics, they think of fanaticism (taʿaṣṣub) as worship (ʿibādat).’Footnote 167 That plurality does not in practice translate into disunity is thanks to ‘the special ones (khāṣṣān) of each community’. Possessing knowledge and wisdom, ‘they do not conceive of the mercy of [god] as specific to a community’. Rather, ‘like sunlight [and] rain … they conceive of [god's mercy as belonging to] all communities. And because heavy burdens result from bigotry and obduracy, they live with friends in harmony and with enemies without quarrel.’Footnote 168 These ideas strongly echo the philosophy of ṣulḥ-i kull (‘universal peace’), which crystallized in Akbar's reign and was closely associated with his ‘House of Worship’.Footnote 169 The histories gloss ṣulḥ-i kull as a purposeful response to the fact of plurality. Akbar believed god ‘bestowed on people differences in disposition and variety in doctrine’, and ‘viewed with kindness the communities of mankind and the classes of people’. In keeping with this divine dispensation, Akbar urged ‘Muslims and Hindus and Zoroastrians and Christians and other religious people (ahl-i mazāhib) to exist with one another in a state of ṣulḥ-i kull’ so that ‘anyone may worship the creator according to his own religion and customs’.Footnote 170

It is implied that the Mughals were acutely conscious of plurality as a basic reality of their world.Footnote 171 With the requisite knowledge (ʿilm), and an attitude consonant with the corporatist ṣulḥ-i kull, plurality could be managed to facilitate cohesion of the imperial polity at large. This is reflected in the near absence of discussion of the jizya, the poll tax on non-Muslims communities traditionally levied by Islamic rulers. The one occasion on which it is discussed concerns its abolishment by Akbar. That happened, so the authors say, because the great wealth ‘in the treasuries’ of the regime and the obedience of ‘all the rājās and rāis’ meant there was no longer any rationale for the jizya.Footnote 172 Moreover, abolishing it harmonized with Akbar's purported opinion that ‘the duty of padshahs is not to foster religious antagonism and dispute [but] to treat well the slaves of god … and confer special favours on everyone equally’.Footnote 173 Relatedly, the histories display no more than (at best) a passing interest in conversion to Islam or in extending the reach of Sharia.Footnote 174 Islam and Sharia as doctrines have no significant place in their interpretations. This is not to say, however, that religion or, perhaps more accurately, orthodoxy were unimportant. So, generic Islamic norms seem to underpin many of the judgements of the authors regarding the actions of particular individuals and communities. The authors also show keen awareness of the multiplicity of mazāhib and mashārib among the subject population. But notwithstanding the regime's formal adherence to Ḥanafī Islam, these traditions are treated in a broadly agnostic and even-handed manner. Money grants were made to both temples and the ulema on the accessions of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb.Footnote 175 Akbar is mentioned as giving material help to the Sanyansis (ṭāʾifa-i Sanāsiyān) of Patiala who had been quarrelling with the local Muslim dervishes (fuqarāʾ-yi Muslimīn) and suffered at their hands,Footnote 176 while Aurangzeb ordered the suppression of the Afghans of Kabul who ‘had broken his nāmūs’ by desecrating the ʿAlī Masjid and a Hindu temple (but-khānah).Footnote 177

Much is made in the histories of margins being important to how the Mughal world was conceived by its elites, which in turn influenced how they addressed its unity. Internal margins were defined by areas that lay beyond the imperial purview and yet were surrounded by territories under Mughal control. These appear to have been relatively small in scale, with rulers classed as independent (mustaqill) or exercising independence (istiqlāl). They existed outside the architecture of the empire and were seemingly either tolerated or ignored. Greater prominence is given to margins forming the external borderlands or frontiers (marz, sar-ḥadd, ḥudūd) of the imperial polity. These come into view most forcefully in reports of invasions, or the threat of them. Thus, unsurprisingly, margins are central to how the histories interpret the rise of the Mughals, which, of course, began with an invasion. In the authors’ narrative, their origins lay within the area of Turan (mā warāʾ al-nahr), in today's Central Asia, where Babur was born and brought up. But the actual campaigns towards the Indus and Lahore were waged from his subsequent base in Kabul. Babur's goal was the conquest of what is termed Hindustan (or more rarely Hind), which he attempted on several occasions.Footnote 178 Following his eventual success, Mughal history is presented by all four authors as anchored in this area, in the upper half of the Indian subcontinent.Footnote 179

The northwest frontier from which Babur hailed is portrayed as a continuing source of instability for Hindustan long after the first Mughal padshah's death. We are told of a plot by Muḥammad Zamān who, on being ejected from Badakhshan, sought to wrest Kabul from Akbar's empire.Footnote 180 Later, after learning of Jahangir's death, Nadhar Muḥammad Khān attempted to capture Kabul from Balkh.Footnote 181 Though both failed in their aims, their actions served as reminders of a geographical vulnerability which the ruling elites ignored at their peril. This accounts for the strategic importance accorded by the authors to Lahore as a gateway between Hindustan and Turan by way of Kabul. Adequately fortified, it shielded Hindustan and, at the same time, furnished a base for Mughal campaigns to the frontier. Not doing this, however, portended the opposite: an under-protected Lahore, because of its luxuries and supplies, would inevitably draw towards Hindustan enemies from the frontier.Footnote 182 Abutting this frontier were the borderlands with Safavid Iran. Though after Humayun's return in 1545 no invasions emanated from there over the period covered by the histories, its possibility was never dismissed, not least because of the very fact of Humayun's restoration. The authors flag that possibility by noting the sustained interest of Mughal elites in the military and political situation of Iran under the Safavids. In part, this was satisfied by official envoys to the Safavid court who brought back valuable intelligence for the padshahs;Footnote 183 in part, it was satisfied by Mughal officials posted to the borderlands, like Khavāṣṣ Khān sent by Shah Jahan to Qandahar, who were there not just to guard and administer the area but also to keep ‘informed about the [Safavid] shah because of [his] proximity to the border’.Footnote 184 The area's vulnerability is demonstrated by the fate of Qandahar. This, the histories testify, was repeatedly fought over by the Mughals and Safavids down to Shah Jahan's reign (after which it remained in Safavid hands).Footnote 185 Similar reasons caused the Mughals to worry about the frontier on the other side of Hindustan, in the east. This extended into the areas of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha, whence several invasions were launched into the empire's heartlands. By far the most significant, and deemed formative for later Mughal history, were the series of military campaigns led by Sher Shah.Footnote 186

So, several of Hindustan's frontiers and borderlands figure in the histories because of their potential to destabilize the imperial regime. Other areas on the margins of the Mughal world did not pose such a threat but nevertheless attracted increasing attention over time. The authors explain this as a reaction to unexpected developments. In one typical pattern, the padshah would despatch officials to remind local rulers of the need to obey the imperial writ and warn them of the consequences of failing to do so. In a second pattern, armies would be sent to suppress uprisings and enforce pre-existing arrangements. A combination of these patterns is marshalled to account for Mughal expansion into Gujarat in Humayun's reign,Footnote 187 Kashmir in Abkar's reign,Footnote 188 and Assam in Aurangzeb's reign.Footnote 189 The Deccan falls into this category, too. According to the histories, of all such marginal areas, the Deccan most exercised the Mughal elites once their regime in Hindustan had been consolidated. Hegemony over this area was initially established under Akbar. What began as an entanglement in a succession dispute ended with part of Niẓām Shāh's territories being incorporated into the regime. In addition, the ʿĀdil Shāh rulers of Bijapur and the Quṭb Shāh rulers of Golconda, while retaining autonomy in their internal affiars, formally became Mughal tributaries and tax collectors.Footnote 190

The authors narrate an unstable dynamic between the Mughal regime and the Deccani rulers after Akbar. Agreements entered into were frequently observed in the breach, necessitating repeated Mughal interventions in the reigns of Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb. Each intervention follows the same basic script. News would reach the Mughal court of a breakdown of order in the Deccan, most commonly seen as uprisings or rebellions against the empire and the oppression of ordinary people. This was often accompanied by local rulers being remiss in paying their annual tribute (pīshkish) or remitting their taxes. In response, a military campaign would be launched from the north to warn and chastise (tanbīh, mālish). Order would be restored and the defiant ruler humbled. The Mughals might also take into direct control further territories in the Deccan and seal new matrimonial ties with the defeated ruler's family. In this way, the area and its rulers reverted to the imperial fold. A few years later, however, the expected tribute or taxes would fail to reach the central treasury, disobedience would become rife, or locals would act to undermine or break free of the empire's hegemony. In due course, a Mughal army would again be sent into the Deccan to put the situation to rights. And so the cycle continued.Footnote 191 It was not until the 1680s that a serious attempt was made to replace this cycle with a fresh dynamic. Frustrated by the rulers of Bijapur and Golconda not giving due support to Mughal officials in the Deccan and by their inability to keep the troublesome Marathas in check and maintain order,Footnote 192 the authors report that Aurangzeb decided on a major offensive against the area's rulers. Over the next few years, the Mughals ground out victories, culminating with the capture of Bijapur and Golconda.Footnote 193 Then, in place of the pre-existing dynamic, Aurangzeb annulled Deccan's autonomy and, so the histories claim, integrated the area into his regime's centralized system of revenue and political administration.Footnote 194

Stepping back from the details, the views above associate the outside world with invasions and conflicts. These had an important bearing on the cohesion of the imperial polity. But the histories do not stop there; the outside world had a bearing on cohesion for other reasons as well. It offered those who had been defeated the prospect of sanctuary. Iran is proverbial in that regard. This drew strength from the positive manner in which Humayun's sojourn there was remembered.Footnote 195 The memory did not just cement Iran as a quintessential place of refuge for Mughal elites on the run; it also offered hopes of a homecoming. The authors mention several who followed Humayun's example, most notably Shah Jahan's son Muḥammad Murād Bakhsh (who returned) and Aurangzeb's son Muḥammad Akbar (who died there in exile).Footnote 196 The Deccan, too, is noted as a place where opponents of the padshah took refuge or went into exile.Footnote 197 Its attraction stemmed partly from the area's many local rulers who themselves were resentful of the Mughal empire's presence. But because of undertakings made to the padshah in exchange for a free hand in their internal affairs, the principal Deccani rulers—the Niẓām Shāh, ʿĀdil Shāh, and Quṭb Shāh sultans—tended to exercise caution in dealings with rebels or rivals fleeing into their territories from the north. The histories convey the sense that support from these rulers was seldom forthcoming unless the arrival of the opponent coincided with their own plans to overthrow Mughal hegemony. This calculus began changing, however, with the rise of Marathas power in the Deccan from the middle of the seventeenth century. It would appear that the Maratha leaders never entered into a durable agreement with the padshah or his tributaries. Rather, they are portrayed as operating largely beyond the purview, let alone control, of the Mughals. This raised the profile of the Marathas and, for the padshah's opponents, made them increasingly credible as allies.Footnote 198

Refuge and exile abroad intersected with diplomacy. Diplomacy, as the authors articulate it, was the means by which the Mughals formally recognized and dealt with elites elsewhere. In the process, they defined themselves and their conception of the Mughal world. Diplomacy manifested itself in a variety of ways. The histories frequently refer to the exchange of gifts, correspondence, and embassies between rulers. These bear witness to systemic linkages between the Mughal regime and a host of regimes abroad. Intriguingly, none of these was located to the east or to the south of the empire; all were situated within areas of Eurasia where Persianate or Islamicate norms prevailed. The most intensive relations seem to have been with rulers in Iran and Turan, whose territories abutted those of Mughal empire to the west and northwest. Over the period covered, the number of diplomatic exchanges with these rulers significantly outnumber those with any others.Footnote 199 Iran is depicted as encompassing, or being synonymous with, ʿIrāq and Khurāsān. These areas were governed by a cohesive regime headed by a shah, who is usually designated by the relatively humble vālī, or very occasionally farmān-ravā or dārā. In contrast, the picture of Turan is more fragmented. While Samarkand and Kashghar are mentioned,Footnote 200 Turan for the authors primarily meant Balkh and Bukhara. These places were at times ruled over by their own separate vālīs, at times jointly by a single overarching vālī.Footnote 201 Looking farther afield, there were rulers of regimes clustered in and around Arabia, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea with whom the Mughals kept up relations, albeit at a lower intensity. So, we see talk of the sharīfs of Mecca and Medina,Footnote 202 the imām of Yemen,Footnote 203 the ḥākim of Hadhramaut,Footnote 204 the ḥākim of Ḥabshah (Abyssinia),Footnote 205 and the ḥākim of Basra.Footnote 206 Most distant of all in the shared diplomatic world of the Mughals was the Ottoman ruler, generally referred to as qaiṣar or farmān-ravā.Footnote 207

Though gifts and correspondence between rulers could be conveyed by couriers, more often this appears to have been done by envoys at the head of official embassies.Footnote 208 The histories recount embassies passing back and forth between rulers on a regular basis and being a common presence at court. Led by the foreign ruler's personal representative, variously termed īlchī, firistādah, safīr, or rasūl, the suggestion is that every help and courtesy was extended to them while in Mughal territories. By the same token, the Mughals took a keen interest in the treatment of their envoys abroad.Footnote 209 The diplomatic norms are at their most explicit in the account of an Ottoman embassy headed by Saiyid Muḥyī al-Dīn to Shah Jahan's court in the early 1650s. Its details exemplify the typical pattern.Footnote 210 The envoy was an honoured guest from the moment he reached Mughal territory until his departure. He travelled to court where he remained at the padshah's pleasure. On given permission to leave, he went laden with valuable gifts, carefully enumerated and costed, for his ruler (and often for himself), as well as with money to cover the expenses of his journey. Letters from the Mughal side to his own, however, were not normally consigned to him. Rather, they were sent in the hands of a courier specially commissioned by the Mughals or entrusted to an envoy leading a Mughal embassy to the foreign ruler's court. This exchange of correspondence, gifts, and embassies between the courts of the region was part-and-parcel of an ongoing circulation of valued objects, information, ideas, and people between the ruling elites of an array of polities. The picture is one of mutually constitutive polities in a shared ecumene, stretching in one direction from the eastern Mediterranean to the Bay of Bengal, and in the other from the shores of the Arabian Sea to those of the Caspian.

The Mughal world's unity is presented as strongly bound up with the character and actions of the regime's allies and opponents. For the initial phase of Mughal history, the authors stress the formative role played by foreign allies. Thus, in Babur's eventual conquest of Hindustan, encouragement was received from several of Sultan Ibrahim Lodi's umarāʾ who had turned against their ruler because of his disrespectful behaviour towards them in court early in Ibrahim's reign and the later imprisonment and murder of two of their number.Footnote 211 The first steps in the recovery of Hindustan by Humayun were, it is said, indebted to his alliance with the Safavids. On his return in 1545, he came at the head of an army to which Shah Ṭahmāsp had contributed ‘a ṭūmār of twelve thousand cavalry and the command of [his son] prince Mīrzā Murād … with a ṭūmār of supplies … And there were nearly twenty-five [of his] umarāʾ … in that army. And beyond that, 300 personal cuirassiers were also assigned to [the army].’Footnote 212 In exchange, Humayun undertook ‘to hand over Qandahar fort to the Shāh's people after [their] victory’.Footnote 213 Though considerable progress was made by Humayun, at his death the reconquest of Hindustan proper from the Suris and their successors remained a desiderata.Footnote 214 One of the principal blockages was Sikandar Shāh Sūr, who continued to resist by organizing Afghan forces against the Mughals. Very early in Akbar's reign, an army was despatched to suppress him.Footnote 215 Confronted by superior forces and disheartened by news of Mughal successes elsewhere, Sikandar submitted, begging Akbar to forgive him his sins. The Mughals did not just forgive him; they assimilated him and his family into their elites, bringing to heel a dynasty whose head had once been their padshah's most fearsome and successful enemy.Footnote 216 Granted a jāgīr, ‘it was decreed that Sultan Sikandar will go towards Patna [and], having taken that country from the Afghans, become [its] mutaṣarrif, and his son will come before [Akbar and] undertake service’.Footnote 217 Thereafter, while no further alliances with foreign rulers are documented in the histories, the Mughals were willing to give sanctuary to leading members of regimes in their near vicinity, particularly to those recently deposed.Footnote 218