Learning Outcomes:

Understand the characteristics of culture and cultural difference

Explain the Social Brain Hypothesis

Describe systems of values and ethics

The Bird’s-Eye View of Culture, Health, and Illness

For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.

Half a million years before internet searches, hundreds of millennia before social media, our earliest ancestors came to one overwhelmingly crappy realization: people die. Of course, creatures have always died, as any trilobite could attest had they survived, but paleontology tells us that cognitions about death began to affect hominid behavior long before we evolved into our present form. Anthropologists know this because earlier pre-humans started choosing particular final resting places, adding special touches, and leaving flowers and trinkets to accompany the departed as they lay, forever unmoving, while the quick continued on (Carbonell & Mosquera, Reference Carbonell and Mosquera2006). That realization of mortality jumpstarted humanity’s continuing saga of cultural creation, fueling our quest to heal or avoid illness and to balance suffering with joy and beauty while we live.

By 80,000 years ago, a cataclysmic drought had devastated Africa for 30,000 interminable years. Myriad species faded forever from the world, including nearly all of our hominid cousins. One isolated group of perhaps 700 individuals remained, whom DNA evidence identifies as our common ancestors, living on the coast of what we now call South Africa at the Blombos Cave (d’Errico et al., Reference d’Errico, Henshilwood, Vanhaeren and Van Niekerk2005; Gugliotta, Reference Gugliotta2008; Henn et al., Reference Henn, Steele and Weaver2018; Mellars, Reference Mellars2006). A quirk of climate gave them a fighting chance, but something greater was afoot. Some combination of factors allowed this plucky bunch not just to survive but to thrive in every region of the globe as they traveled across continents and seas. And flourish they did, with 8 billion descendants now spread across the planet attesting to their success. We all share snippets of their DNA, 75,000 years later. We are the living evidence of their adaptability, ingenuity, and collaboration, traveling always toward the hope of an ever-greater future, though never able to evade our dreaded companion, mortality.

Spinning many thousands of times more around our modest yellow star, we forgot our common origins on that windswept coast. As we wandered to the furthest reaches of the Earth, we adapted and changed at a pace that has accelerated steadily throughout history, making us more and more different. At this point, we are so unlike each other that we speak mutually incomprehensible languages and our beliefs are so divergent that some feel compelled to kill others to prove whose ideas are right. If there is anything obvious about cultures, it is that we think differently.

These many thousands of years later, we remain remarkably similar to those ancient ancestors and to each other in the details of those twined strands of DNA. We all continue to enter the grand stage of mortal drama through the same feminine portal of biologic creation. Our finales, however, are a marvel of variety as we eventually shuffle off our mortal coil in myriad ways on our journey to the ultimate resting state. Humans have culture; death does not. As English poet Edward Young (1683–1765) lamented, “Life is the desert, life the solitude; Death joins us to the great majority.” Until we reach that day, we can do our best to understand and help each other along the way because, though our finale may be highly individualized, we eventually arrive at that same unfathomable destination.

Humanity’s Improbable Survival

Humans are strange creatures. I refer not to the individual eccentricities that entice millions to watch reality TV. Rather, our species has characteristics unlike other inhabitants of our tiny planet. We lack defenses of claws, fangs, or scales. More often than not, a chimpanzee can bite the face off the most physically fit of human specimens. We are neither fast enough to outrun an alligator nor well camouflaged enough to hide from any carnivore with a good nose and sharp eyes, yet somehow we survived and spread across the globe. We interact in larger groups than other mammals, though insects have us beat in terms of local community size.

We live longer than most creatures, a surprising fact given our frailty, but unlike a horse or deer who stands and walks within hours of birth, we begin life unable to feed, clean, or protect ourselves for years. Fortunately, we evolved neurochemicals that stimulate bonding, amplifying our tendency to consider baby creatures adorable, because any helpless, squirming, squalling, pooping human bundle of joy depends completely on others for survival. Those around us, parents, relatives, friends, and neighbors, help us learn basic life skills relevant for our socioecological context. We coexist and cooperate in a reciprocal web, giving to and receiving from those around us in lives of what Caporael and Brewer (Reference Caporael and Brewer1995) term obligatory interdependence. We have depended on our social groups for basic needs since before we were morphologically human. Our venerable progenitors, families, tribes, villages, and trade networks perpetually facilitated our existence, evolving over the eons into expansive groupings of economies and governments, which are really just mechanisms for large-scale interdependence and cooperation. Eventually these became the cultures surviving today.

Very Large Heads

Another odd thing about humans: our brains are unexpectedly large for our size, compared to other creatures, dubbed our encephalization quotient (EQ) (Jerison, Reference Jerison1955). Theorists have proposed a variety of explanations for those big brains. For decades, the popular idea was that big brains developed to facilitate tool-making, but changes in cerebral capacity did not parallel advances of material culture as well as they reflected changes in social group size. The Social Brain Hypothesis (Dunbar, Reference Dunbar2009) says our strangely large brains evolved to facilitate interactions in larger groups than even other primates. In the absence of claws, fangs, or speed, we desperately needed some other advantage, and our unique advantage was group cooperation.

Murders, wars, and antisocial psychopaths notwithstanding, the overwhelming thrust of human activity is cooperative and mutually beneficial. The legendary anthropologist Margaret Mead reputedly said, when asked about the earliest evidence of human civilization, that it was the discovery of an ancient skeleton whose broken femur had healed, because no animal will survive that injury unassisted (cf. Moodie, Reference Moodie1922). Nurtured back to health by its social group, that early ancestor’s recovery demonstrates what have been called humanizing influences. Funny how our languages equate the highest and best moral urges with our own species. Evolution operationalizes its effects simultaneously on multiple levels from cells to organisms to societies; for humans, group life became their primary survival strategy and locus for evolutionary adaptation long ago (Brewer & Caporael, Reference Brewer, Caporael, Brown and Capozza2006).

Breakfast for the Family

Those expanding brains had a few unforeseen consequences. One was the ability to observe, remember, and improve actions, allowing human existence to ratchet, not inexorably but mostly, toward ever more effectively complex material and technical abilities (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello1999). Another effect drove the blossoming of aesthetic and intellectual culture because we had a looming problem. We have great memories and the ability to mentally time-travel into both the past we can recall and to any future we can imagine. We observe and remember the deaths of those around us and have the ability to imagine our own. We are ticking time-bombs doomed to live, breathe, and expire, probably dying before we want to, often in some awful way, and like it or not, we know it inevitably will happen.

This starkly egalitarian menace provided us with an overwhelming quandary: how could we keep getting up every day to forage food for our helpless offspring, knowing a thousand ways to die awaited us? One way is the atrophy of the amygdala after severe trauma (e.g. Morey et al., Reference Morey, Gold, LaBar, Beall, Brown, Haswell and McCarthy2012), a key structure for memory consolidation, the shrinkage of which has been observed in autopsies and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of people with severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We strategically forget the worst trauma, to some degree. More normally, we find ways to express our angst, and we desperately seek distraction (Becker, Reference Becker1973; Routledge & Vess, Reference Routledge and Vess2018). Terror Management Theory proposes that culture may have resulted from our need to distract ourselves from looming mortality. We maintain functionality by singing and dancing, carving ornaments, and, more recently, creating mountains of paperwork to occupy our minds. This will be addressed in more detail later, but with all these tasks and distractions, we don’t have time to think much about dying.

Culture also provides a marvelously practical solution to personal mortality; physically, my genes survive in those related to me, and metaphorically, culture allows long-term survival as a member of an ongoing social group that shares behaviors, beliefs, and values. Indeed, many cultures place great importance on the intergenerational transmission of what we call traditions, whether following a set of religious proscriptions or turning tracings of American children’s hands into turkeys in November. Identification as a member of a group with ongoing practices and beliefs means I have some measure of immortality because I can expect that group with which I identify to live on beyond my own demise. Some cultures institutionalize group immortality with traditions celebrating ancestors, such as ancestral veneration rituals in East Asia or Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, in Mexico. In those events, we memorialize our ancestors with our friends, families, and especially our children, and we expect our descendants to celebrate us in similar fashion, cementing our place in an ongoing chain of ethnocultural existence that will outlive us. If I am not personally immortal, which our robust brains cannot help but notice, I can sleep peacefully at night because I know my culture will live on.

Defining Culture?

Every time I hear the word culture I release the safety on my 9 mm.

A barely hidden desire to create a shopping list of cultural characteristics is sometimes discernible: Tamils do this, the Cree do that, and Guatemalans do the other, in order to systematize and “tidy up” culture in the same way as are other epidemiological variables such as smoking, age, gender, or fertility rates.

Of all of the egregious inconsistencies of the English language – different spellings that sound the same, identical spellings that sound different, grammatical rules broken helter-skelter, and words with multiple meanings – the word culture must rank among the most confusing. It can mean a large group of people with common history and customs, such as Serbian culture. It can be the refined characteristics of certain segments of a society, like a cultured Xhosa person with expertise in their culture’s practices. Culture can be artistic activities and products, like totem poles or items one finds at an art gallery, or a night at the opera. Culture can be a Petri dish of growing bacteria. With no disrespect to the bacteria, we will only discuss culture as it pertains to groups of people and certain relevant characteristics of those groups, though we will find that the “culture” of arts and music may provide paths to understanding the “culture” of groups. For our working definition, we will say that “Cultures are constellations of thought and behavior characteristic of a particular group of people, transmitted non-genetically across generations, by which meanings and identities are created and shared” (Fox, Reference Fox2020, p. 10).

To unpack that infernally academic statement, humans live in groups that act differently from place to place, with the differences amplified over centuries and distance from their common origins. We certainly behave peculiarly when viewed from outside our own cultures. Unique cultural behaviors reflect underlying ideas. We pass those ideas to generations that follow us and they become normal. Those collections of thoughts and ideas tell us who we are, who belongs with us, and how to make sense of the crazy world around us.

Broadly defining culture helps our intellectual grasp, but we need something more practical here, a way to understand how culture works in our lives and hearts on a daily basis. A very Western, Cartesian approach is to break concepts or phenomena down into components, which is how we will begin, but really, culture is a holistic lived experience. The clearest sources of perspective on culture are either examples from one’s own cultural life for familiarity or from a very different lifeway for contrast, and we will explore a number these as our discussion moves onward.

Finding Your Culture

Task 1.1 Considering Your Culture

Please take a moment to think about what is normative for your life.

What holidays do you celebrate (if any)?

What is customary activity for those holidays?

Do you take off your shoes when entering a home or sacred space?

What can you discuss with your grandmother?

What can you say to friends that you would never say to your grandmother?

What constitutes a vacation?

Can you talk back to your boss?

How did you learn the answers you gave?

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously said, “Behavior is a mirror in which everyone shows his image.” Culture and cultural difference appear most readily in how people act. The questions in Task 1.1 indicate some basics of how people might behave in your culture (or cultures). If the answers readily leapt to mind, you may have grown up in a monocultural family or a local context sharing ancestors from similar cultural backgrounds. After centuries of colonization and migration, you may have multiple ancestral lines and your habits may include diverse customs and cuisines. Whatever your personal genealogy, the answers to those questions will provide only superficial clues to your culture because culture is like an iceberg, most of it hidden beneath the surface. Underlying your answers are systems of belief generated and refined over millennia.

Box 1.1 Shoes: On or Off?

One habit that differs across cultures is removal of shoes when entering certain structures, such as homes or ceremonial spaces. Shoe removal is normal behavior in Asian and Polynesian cultures but not in European or Euro-American life. Shoe removal is but the visible portion of beliefs about hygiene and sacredness, translated into behaviors in slightly different ways. Europeans were infamous for their resistance to bathing as they colonized the world; perhaps their feet and foot odors were best kept encased for the greater good.

Asia and the Pacific region have a different view of shoes, partly because they track in dirt, disease, and disorder. You will not be welcomed in a Buddhist temple with your shoes on. A home in Japan may have house shoes available for guests to exchange for their own as they visit, while Euro-Americans may be quite confused if you take off your shoes when entering their homes. At a home in Hawai‘i, guests will leave a pile of shoes by your door and walk in barefoot. Removing shoes leaves the bustle and pathogens of the world outside, protecting the sanctity of homes, temples, and whare nui. Similarly, I have seen Māori wince and turn a bit green when someone sits on a table because the posterior is kapu (taboo in colonial English spelling), and that table has then been rendered unclean for serving food. The kapu system doubles as a guide to public health far better than anything Europeans dreamed up before the twentieth century.

Hygiene forms an unspoken practical factor in shoe removal, while sacredness and respect exemplify beliefs and values underlying the behavior. Shoes can track in literal feces, while metaphorically they carry in the turmoil of life. If you respect the health, humanity, and dignity of the host, you don’t soil the carpet or sully the sacredness of the space.

Now ask yourself what you believe. What is true? What is good? Is it better to be honest or rich? Is theft okay if it saves a life? Is all fair in love and war? Is there a Santa Claus? Are people inherently naughty or nice? Behaviors are easy; we can see and measure them. Beliefs are more difficult, though people can generally describe their specific beliefs. Even more subtle are values, the guiding principles “seen to shape and justify the particular beliefs, attitudes, goals, and actions of individuals and groups” (Dobewall & Rudnev, Reference Dobewall and Rudnev2014, p. 46). We learn the values of our culture over time and mostly without our awareness or intention.

Human cultures include what was passed to you by your ancestors from your ethnic heritage. Culture may be a national amalgam of traditions brought by people of multiple ethnic origins, leading to the melting-pot and salad-bowl metaphors for “American” culture. Large groups within a nation may create systems of thought and behavior transmitted through time with enough fidelity to have characteristics of a culture themselves, such as the US military. American sports including football have remarkably consistent cultural patterns, with rules, hierarchies, fan and player behaviors, marching bands, and so on, and could be considered a subculture. Komarovsky and Sargent (Reference Komarovsky, Sargent, Sargent and Smith1949) defined subcultures as “cultural variants displayed by certain segments of the population” (p. 143), and the term enjoyed widening use as hippies and rock and roll upended social norms in what Yinger (Reference Yinger1960) described as counterculture.

For the purposes of this book, the term “organizational culture,” championed by Edgar Schein (Reference Schein1952/2010), may be useful. Schein emphasized predictability and patterning based on non-negotiable underlying assumptions as hallmarks of culture. These could be found to varying degrees, he said, from global culture down to subcultures and microcultures of departments, offices, and teams within individual businesses.

He differentiated three levels of culture: macrocultures, including nations, religions, and globally present occupations; organizational cultures, which are public, private, and governmental organizations; subcultures, which Schein defined as occupational cultures within organizations; and microcultures that include teams both within and outside of organizations. The healthcare industry and its components have elements on all of these levels, with macrocultures including doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers all over the world; organizational cultures of healthcare systems as widespread as the US Veterans Administration with over 400,000 employees; subcultures that could include hospitals or their departments or professional organizations like the American Psychiatric Association; and microcultures that could be as small as specific medical practices or surgical teams. Schein (Reference Schein1952/2010) pointed out that in a globalized world, large organizations will likely draw on multiple macrocultures, which we will see is true up and down levels in the healthcare industry. For the sake of simplicity, we will apply the term organizational culture to structures in the current biomedically oriented healthcare system in general and to its component educational and professional institutions.

Values: The Unseen Force

A century ago, McDougall (Reference McDougall1919/2001) proposed that “the fundamental problem of social psychology is the moralisation of the individual by the society into which he is born as a creature in which the non-moral and purely egoistic tendencies are so much stronger than any altruistic tendencies” (p. 25). All cultures include systems of morality, making it a cross-culturally universal concept, but cultures vary incredibly in the content and consequences of those systems, making it a domain of immense cultural variation (e.g. Haidt, Reference Haidt2013). Research into values and morality burgeoned following the horrors of World War II, with people baffled by the cold inhumanity of the Holocaust and the brutality of Japan in Korea, China, and Southeast Asia. Stanley Milgram’s infamous obedience experiment and Solomon Asch’s inquiries into conformity were designed to reveal how seemingly normal people could cast decency to the winds and commit atrocities on a massive scale. Most of the members of the military committing the atrocities probably thought they were doing what they should, obeying orders and furthering their cause while simultaneously violating and upholding other core values. Ultimately, humans mostly behave within the confines and parameters of their cultural context, though they are often unaware of the sometimes contradictory forces motivating them. Social psychologists began to examine ways of thinking and believing, and the resulting systems of values and morality.

Early research in this direction sought ways to help people be healthy and to build a better world, leading eventually to positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000). Abraham Maslow (Reference Maslow1965) envisaged a world in which everyone can blossom into their fullest self-actualization, his hierarchy of needs outlining a humanistic path to ideal existence, providing an antidote to despair and inhumanity. Lawrence Kohlberg (Reference Kohlberg and Mischel1971) famously investigated moral development in childhood and universal mechanisms of morality, saying, “Virtue is ultimately one, not many, and it is always the same ideal form regardless of climate or culture … . The name of this ideal form is justice” (p. 232). Virtue varies across cultures, apologies to Kohlberg, and we still do not have a world in which all can self-actualize, but cultural patterns of values and beliefs provide valuable clues to human behavior. Values shape our approach to healthcare, influencing who makes decisions, how resources are allocated, and what goals we pursue in that domain. We will explore research describing patterns of values across cultures, to be applied later as these patterns affect people’s understandings, decisions, and well-being.

Measuring and Mapping Values

International business kicked into high gear after World War II, extracting resources, building factories, and sending products all over the world. A practical line of research was funded by the new multinational corporations expanding their manufacturing and sales workforces internationally. Manufacturing had accelerated to fever pitch, churning out the machines of war; the US and its allies gained sudden access to resources and markets beyond their wildest dreams. Problems quickly arose, however. At every level, from managers, to labor, to sales staff, people from different countries and cultures had to work with others quite unlike themselves, often with misinterpretations and misunderstandings resulting. International Business Machines (IBM) took the bull by the horns, hiring Dutch social scientist Geert Hofstede (1928–2020) to establish its office of personnel research and develop ways to understand the difficulties and differences the company was encountering. By 1973, he had collected data from 117,000 employees in 50 countries about their attitudes and values in the workplace.

Hofstede published his analyses in Culture’s Consequences (Reference Hofstede1980), initially proposing five dimensions: Power Distance Index (PDI), Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV), Masculinity versus Femininity (MAS), Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI), and Long-Term Orientation versus Short-Term Normative Orientation (LTO). He later added the sixth dimension of Indulgence versus Restraint (IVR) in subsequent decades of copious research. The dimensions of cultural variation he identified have become a standard in industrial and organizational psychology and human resource management. More recently, the Masculinity dimension has been renamed Motivation towards Achievement and Success. The Hofstede-Insights website provides tools to compare country-level scores on the dimensions shown in Table 1.1. Scores from 2023 for the US, China, and Brazil are included to demonstrate the contrasts, but many scores from many countries are available on the website.

Table 1.1 Country-level scores on Hofstede dimensions of cultural difference (Hofstede-Insights.com, 2024)

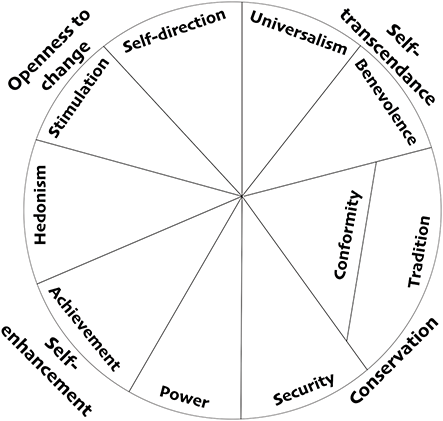

In cultural and cross-cultural research, other streams emerged examining the components of morals and values to describe and systematize their differing manifestations across cultures. Schwartz and Bilsky (Reference Schwartz and Bilsky1987, Reference Schwartz and Bilsky1990) proposed that all values spring from underlying goals and motivations, and that, regardless of culture, all values contribute to three universal existential requirements: “needs of individuals as biological organisms, requisites of coordinated social interaction, and survival and welfare needs of groups” (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz and Zanna1992, p. 4). Putting these requirements into practical application should, they explained, yield a universal matrix of values that vary across cultures. Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2006, Reference Schwartz2012) eventually proposed a set of ten basic human values that would be emphasized or deemphasized by the members of a culture, some opposing like tradition and self-direction, others more closely associated like security and conformity (Figure 1.1). Confirmed by factor analysis of survey data from dozens of countries, the list includes:

(1) Tradition. Respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide the self

(2) Conformity. Restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms

(3) Security. Safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self

(4) Power. Social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and resources

(5) Achievement. Personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards

(6) Hedonism. Pleasure and sensuous gratification for oneself

(7) Stimulation. Excitement, novelty, and challenge in life

(8) Self-Direction. Independent thought and action-choosing, creating, exploring

(9) Universalism. Understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection of the welfare of all people and of nature

(10) Benevolence. Preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact.

Richard Shweder and colleagues (Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997) took a different approach, developing his Big Three ethical dimensions of moral discourse by asking people in the city of Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India how they would respond to moral transgressions in hypothetical situations. The ethical dilemmas presented included “A poor man went to the hospital after being seriously hurt in an accident. At the hospital they refused to treat him because he could not afford to pay” and “The day after his father’s death the eldest son had a haircut and ate chicken.” For the people of Bhubaneswar, these incidents characterized varying degrees of transgression that could expose the transgressor to suffering as consequences (to be discussed later). From the discourses, Shweder and his team (Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997) distilled ethics of Autonomy, Community, and Divinity to explain difference in how people understand and respond to the world (see Table 1.2). The ethic of community would prioritize benefits and loyalty to one’s ingroup. Autonomy emphasizes individual agency – freedom to choose and act based on personal wants, needs, and inclinations. The divinity ethic emphasizes relations with spirit, sacredness, and higher powers; a person must behave in accordance with the rules, codes, and proscriptions of the religion or cultural group to maintain right relations. Keeping kosher or eating halal would demonstrate adherence for Jews and Muslims, respectively.

Table 1.2 Shweder’s Big Three of morality (adapted from Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997, p. 138)

| Ethical dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Community | Relies on regulative concepts such as duty, interdependency, hierarchy, and souls |

| Autonomy | Relies on regulative concepts such as harm, rights, and justice |

| Divinity | Relies on regulative concepts such as sacred order, natural order, tradition, sanctity, sin, and pollution |

These ideas take more or less prominent roles in people’s construction of morality and resolution of ethical dilemmas. The ethics are not independent and each may play a role, though their relative importance changes by culture. The theory also describes reactions to violation of the ethic, including emotional responses such as disgust from violations of Divinity morals. More relevant for this book are the metaphysical penalties incurred for violation, which might provide explanations for misfortune or illness (Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997).

Building on Shweder’s concepts, a more recent group including Jonathan Haidt, Jesse Graham, and Craig Joseph proposed Moral Foundations Theory. Like Shweder, they rejected the monistic idea that all morals stem from a single core value (e.g. justice for Kohlberg) or other single sources such as sensitivity to harm or welfare and happiness (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik, Ditto, Devine and Plant2013; Haidt, Reference Haidt2013; Haidt & Kesebir, Reference Haidt, Kesebir, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010). The group included social and cultural psychologists who agreed that cross-cultural variation requires a sophisticated set of parameters to explain the myriad differences in moral constructs. Cultural variation also implies that values are learned, and as such, people in one culture may have no understanding of a core construct in another. Graham and colleagues (Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik, Ditto, Devine and Plant2013) give the example of a Hindu girl who grows up automatically bowing to respected elders, contrasted with an American girl who has no awareness of hierarchies or requisite respectful behaviors.

Moral Foundations Theory includes five foundational pairs of opposing values: Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation (Table 1.3). The model provides nuanced explanatory power based on the degree to which ethics are emphasized in a given culture. All of these moral theorists, from Kohlberg to Shweder, to Haidt and his colleagues, operate under the certainty that these systems are learned in childhood or there would be much greater similarity across cultures. Processes of enculturation, the ways we learn and adopt our cultures, provide another path to intercultural insight.

Table 1.3 The original five foundations of intuitive ethics (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik, Ditto, Devine and Plant2013, p. 68)

Making Sense of a Confusing Landscape

At this point, you have read several different, possibly contradictory, views of foundational elements of culture. Which is correct?

Perhaps all are correct, at least to some degree. Theoretical models arise based on researchers’ experiences, observations, and inclinations, meaning each may be valid from a particular perspective. These theoretical models differ in structure but all serve the same purpose, attempting to explain why people act and think as they do. Your culturally informed level on Hofstede’s Uncertainty Avoidance dimension might affect how comfortable you are with the discrepancies between the models.

Cultures have no immutable demarcations. They are complex assemblages of ideas, materials, and practices collected over millennia to address problems, challenges, and opportunities of particular environments, some shared from one culture to another, passed imperfectly down through generations. Variation between cultures and within cultures means that everybody falls somewhere on a sliding scale on any measurable factor; there are no absolutes. Theoretical models, though imperfect, provide structure through which to examine, compare, and contrast these aspects of human existence.

Summing Up

It is often hard enough to understand the people in our own families, much less those who see the world very differently. This module moves us toward better understanding of people from other cultures by examining some differences and why they exist. Interpersonal understanding requires parameters by which we can gauge and predict how people may think and act, which we usually absorb during childhood in a particular culture. From the foods we eat to the wars we wage, values form the basis of our decisions, at least those we make consciously, and awareness of how different cultures emphasize particular ethical values might help us understand even the most baffling decisions. These concepts will come into play as we discuss issues like informed consent, help-seeking, and decision-making hierarchies in healthcare.