Several recent studies have raised concern that contaminated floors might be an underappreciated source of transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens. Reference Donskey1–Reference Janezic, Blazevic, Eyre, Kotnik Kevorkijan, Remec and Rupnik8 In an observational study, high-touch items in patient rooms were often in contact with the floor. Reference Deshpande, Cadnum and Fertelli2 In patient rooms, a nonpathogenic virus inoculated on the floor disseminated to the footwear and hands of patients, to surfaces in the room, and to adjacent rooms and nursing stations. Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey3 In rooms of newly admitted patients, healthcare-associated pathogens rapidly contaminated the floor as personnel entered the room, with subsequent detection on patients’ socks, bedding, and high-touch surfaces. Reference Redmond, Pearlmutter and Ng-Wong4

Mopping or spraying with disinfectants or ultraviolet light can reduce the burden of pathogens on floors. Reference Mustapha, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey9 However, contamination reaccumulates rapidly, and such strategies do not address floors outside the room. Thus, there is a need for new approaches to reduce the risk for acquisition of pathogens from floors. In a simulation, we demonstrated that wearing slippers prevented transfer of a benign virus from the floor to feet and reduced transfer to hands and surfaces. Reference Redmond, Pearlmutter and Ng-Wong4 Here, we conducted a randomized trial to determine whether having hospitalized patients wear slippers would reduce transfer of a benign virus from floors to surfaces and patients’ hands.

Methods

The Cleveland Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center’s institutional review board approved the study protocol. From August 1, 2020, through April 20, 2021, we conducted a nonblinded parallel randomized trial of a slipper intervention versus standard care for a convenience sample of patients admitted to 2 medical-surgical wards with anticipated length of stay of at least 2 days. Patients were excluded if they had dementia, decreased mobility, or were under contact precautions. Patients were randomized using computer-generated random numbers.

For the intervention group, open-toe adjustable slippers (Dena Lives) were provided, and patients received education on the potential for floor contamination to be acquired on feet. The patients were instructed to wear slippers whenever out of bed and to avoid contact between their feet and/or socks and the floor. Patients received re-education on slipper use during follow-up visits 1 day after enrollment. Patients randomized to the control group did not receive slippers or education.

For both groups, a 30×30-cm area of the floor between the bed and the bathroom was inoculated with a 10-mL suspension containing 1×108 plaque-forming units (PFU) of bacteriophage MS2/mL and was then allowed to air dry. Patients were not aware of the inoculation site and personnel were not aware of the study. High-touch surfaces or floors were not cleaned during admission unless visibly soiled. In preliminary experiments, the MS2 inoculum persisted on floors for 3 days with only a 1–2 log decrease in recovery.

At 24 and 48 hours after MS2 inoculation, sterile, premoistened, BBL CultureSwabs (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were used to sample high-touch surfaces (bed rails, bedside table, call button, telephone), personal items (cell phone, reading material, water bottles), bed linen in the location of the patients’ feet, and the patients’ hands and the soles of the feet and/or socks. For large surfaces, a 30×30-cm area was sampled; for smaller surfaces the entire surface area was sampled. Swabs were processed for culture of bacteriophage MS2. Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey3 Negative control swabs were processed at baseline and at 24 and 48 hours. The microbiologist processing the cultures was blinded to the study group.

Information on demographics, medical conditions, devices, and mobility was obtained through chart review. The primary outcome was acquisition of bacteriophage MS2 on a composite of all sites, including the percentage of sites contaminated and the average log10 PFU. We anticipated that at least 1 site would be contaminated with MS2 in ∼60% of control group participants. Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey3 A power calculation indicated that 17 patients per group would provide 80% power to detect a 75% reduction in contamination from 60% to 15%. Linear and generalized linear mixed-effects models controlling for collection time and contamination site were used to compare the percentages and average log10 PFU levels of contamination for the groups. Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare characteristics of groups. The Fisher exact test was used for categorical data and the Student paired t test was used for normally distributed data. Analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 statistical software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and functions from the lme4 and lmerTest packages were implemented.

Results

Supplementary Figure 1 provides a flow diagram of study enrollment. Of 36 participants, 18 were randomized to the slipper intervention and 18 to the control group; 17 participants in each group were eligible for analysis. We did not detect any significant differences in the characteristics of the participants in the 2 groups (Table 1). Based on interviews, 3 (18%) participants in the intervention group noted at least 1 episode of noncompliance because they forgot to put on the slippers. An additional intervention participant stated that he did not wear his slippers during a physical therapy session at the request of hospital personnel; this participant was observed by research personnel holding his socks after the session and had a positive hand culture.

Table 1. Comparison of Characteristics of Patients in the Intervention and Control Groups

a Units unless otherwise indicated.

b Braden scale for predicting pressure ulcer risk is routinely collected by nursing staff: high risk = total score 10–12; moderate risk = total score 13–14; mild risk = total score 15–18; no risk = total score 19–23.

c Mobility score is a subcategory of the Braden scale for predicting pressure ulcer risk: 1 = completely immobile, 2 = very limited, 3 = slightly limited, 4 = no limitation.

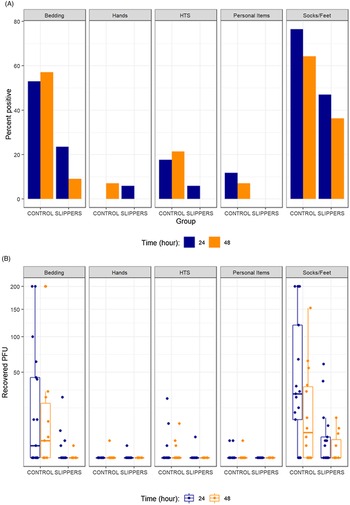

Figure 1 shows the percentage of sites positive for bacteriophage MS2 and the log10 PFU recovered for the control and intervention groups. The number of participants in each group was 17 at 24 hours but decreased to 14 and 11 at 48 hours due to hospital discharges in the control and intervention groups, respectively. In comparison to the control group, the intervention group had significant reductions in the percentage of contamination (odds ratio [OR], 0.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.05–0.50; P < .01) and in the log10 PFU recovered (β = −2.48; 95% CI, −3.78 to −1.16; P < .01). These models also demonstrated significantly increased contamination of socks and/or feet in comparison to other sites (P < .05).

Fig. 1. Percentage of sites positive for bacteriophage MS2 (A) and the concentration (log10 plaque-forming units [PFU]) recovered (B) for control versus slipper intervention groups. HTS, high-touch surfaces.

Discussion

Floors are increasingly recognized as a potential source for transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens. Reference Donskey1–Reference Mustapha, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey9 However, repeated cleaning and disinfection of floors is not practical because contamination reaccumulates rapidly and few alternative approaches have been considered. In the current study, a benign virus inoculated on the floor in hospital rooms was frequently acquired on socks or feet of patients and transferred to high-touch surfaces and hands. Acquisition of the virus was significantly reduced in patients randomized to wear slippers whenever out of bed. These results suggest that having patients wear slippers could provide a simple and low-cost intervention to decrease the risk for acquisition of pathogens from floors.

Although wearing slippers was effective, it did not eliminate all transfer of bacteriophage MS2. The contamination in these cases is likely attributable to participants occasionally forgetting to wear slippers or inadvertently contacting the floor while donning slippers. Further evaluations are needed to determine whether additional education or wearing slippers in conjunction with floor decontamination might be effective in reducing these occurrences. Encouraging patient hand hygiene after contact with slippers or socks may also be beneficial.

Our study had some limitations. The study was conducted in a single institution, and most participants were male and elderly with normal or slightly limited mobility. Compliance of participants with the intervention was not monitored. The transfer of bacteriophage MS2 was studied rather than transfer of healthcare-associated pathogens. However, in simulations bacteriophage MS2 and Clostridioides difficile spores transferred at similar frequencies from a contaminated mannequin to environmental surfaces. Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana10 Future studies are needed to determine whether preventing transfer of pathogens from floors to high-touch surfaces will reduce the risk for acquisition of healthcare-associated pathogens.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.475

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients at the Cleveland VA Medical Center who participated in the study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Conflicts of interest

C.J.D. has received research grants from Clorox, Pfizer, and PDI. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.