I

Staging of Wagner's operas – or ‘dramas’ – has always proved controversial.Footnote 1 Indeed, controversy dates back to the composer-librettist-dramaturge-theorist-director's own stagings. In retrospect, Wagner stakes a good claim to have invented the role of the modern opera director: not only with respect to his own works but also with those of other composers.Footnote 2 Nowhere has controversy fanned more flames than at the Bayreuth Festival and in its Festspielhaus, which Wagner founded and had built expressly to stage the Ring. Moreover, even in a history littered with controversial productions, few have provoked such angry debate as that which opened in 2013 as a centrepiece for the bicentenary celebrations of Wagner's birth, directed by the (East) German director Frank Castorf. Wagner's operas, Castorf, performers and audiences emerged changed, even transformed, by the encounter: by new critical standpoints afforded as the Valhalla mists of operatic tradition were dispelled and by compromises necessitated as much as by the violence and rupture of Castorf's – and Wagner's – thunderclaps.

For Bayreuth had always been a compromise. In theatre, in performance, everything is: even for artists so apparently uncompromising as Wagner, Castorf and many of those working at Bayreuth in between. Wagner's initial plan for the Ring, performance art avant la lettre, had been to erect a temporary theatre on the banks of the Rhine in order to celebrate a successful revolution, which, failure in 1848–9 notwithstanding, would have come to pass by the time of the premiere. The work, as he told Theodor Uhlig, would explain ‘to the men of the revolution the meaning of that revolution, in its noblest sense’; its performance would be followed, in one of several pyromaniacal homages Wagner would pay to his anarchist revolutionary comrade-in-arms Mikhail Bakunin by burning not only the theatre but also the score.Footnote 3 ‘However extravagant this plan may be’, the hopeful composer went on, ‘it is nevertheless the only one upon which I can wager my life, my writing, my energies. Should I witness its achievement, so shall I have lived gloriously; if not, so shall I have died for the sake of something beautiful.’Footnote 4

How seriously one is to take such protestation is an open question. Not for nothing did Nietzsche insist that Wagner was ultimately an actor.Footnote 5 The pages of Wagner's autobiography are replete with the hustle and bustle of actual theatrical life, in a manner and intensity foreign to most composers of what we might still call the Austro-German (instrumental and orchestral) tradition.Footnote 6 Conflict between, on the one hand, the Ring's emphatic status as a musicodramatic work and, on the other, the abiding theatricality both of its creator and of its potential future in performance had been signalled. Both the gathered congregation of Wagner's Bühnenweihfestspiel (‘stage-festival-consecration-play’) Parsifal and his temple of art, Bayreuth itself, represented the former pole, namely that of the composer's authority and Werktreue. Sooner or later, however, other possibilities were bound to re-emerge, especially against a backdrop of post-Holocaust suspicion of totalising tendencies within German idealism, as well as more straightforward German nationalism and opposition thereto.

Notwithstanding crucial antecedents such as the East German director Joachim Herz's Leipzig Ring (1973–6), it was Patrice Chéreau's centenary Ring (1976–80, conducted by Pierre Boulez), only the third Festival production – and the first Ring – since Bayreuth's postwar reopening entrusted to a director from outside the Wagner family, which made the greatest impact on the operatic world and beyond.Footnote 7 This plunging of Wagner's drama back into the political and social conflicts of the nineteenth century ensured that Wagner and the Ring would never be the same again. David J. Levin has gone so far as to speak of a ‘neutron bomb for opera production’. It was, Levin continued, in homage to Boulez's celebrated incendiary declaration of several years earlier, ‘one that left the opera houses standing, but exploded some of their most settled practices’.Footnote 8 Worldwide screening on television played an important part: the latest in a lengthy line of examples of participation and critique by Wagner, his works and their staging in novel technological endeavours.Footnote 9 The BBC showed it one act at a time, not unlike one of its plays for the day: drama, then, and musical drama at that, for a worldwide audience inconceivable to Bayreuth during its first century.

Chéreau's staging proved highly controversial as drama, far from universally accepted as a legitimate method of staging Wagner. It more or less inaugurated a parade of controversial Wagner productions at Bayreuth, rescuing the festival from the doldrums of Wolfgang Wagner, a highly talented administrator, but no artistic match for his deceased brother, Wieland.Footnote 10 The idea of Bayreuth as a theatrical workshop (Werkstatt) was renewed: it was still a venue for model Wagner performances, ever faithful to musical and poetic text, yet not now necessarily to stage directions and ‘intended’ mises en scène.

Henceforth, there was at least fruitful tension, if not outright contradiction, between those tendencies, at Bayreuth and within opera production more broadly. In 2013, immediately before Castorf's Ring opened, Clemens Risi identified the ‘performance practice’ of opera as ‘moving in three different directions’. First, the ‘initially cautious’ deconstructionist, for which he cited as an example a Meistersinger from the Intendant of Berlin's Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Frank Castorf. It was played with actors rather than trained opera singers, much like Castorf used non-actors in place of actors in many plays. Combining texts of Wagner and others, Nietzsche included, with Ernst Toller's 1919 Masse Mensch, all within two-and-a-half hours, this, Risi writes, was so far something of an exception in the operatic world. A second direction was characterised by continued, ‘obstinate’ demands for Werktreue. The third, ‘Regietheater in opera’, retained ‘the musical dramaturgy of the work while at the same time radically questioning, re-examining and recontextualizing the layers of meaning of an opera – layers that are conveyed by all the available texts: the libretto, the full score, and discourses about the work's staging practice’.Footnote 11 Bayreuth had come to stand somewhere between the second and third; it stood and still stands adamantly opposed to the first. With Wagner's authoritative musicodramatic text there could and can be no tampering – although even then, in certain cases, there remains the fraught questions of which version of a score to use, and whether ‘traditional’ cuts may be acceptable.

II

Wagner's lengthiest theoretical work, Opera and Drama, argued the supremacy of musical drama over the non- or anti-dramatic, yet unquestionably theatrical, ‘outrageously coloured, historico-romantic, devilish-religious, sanctimonious-lascivious, risqué-sacred, saucy-mysterious, sentimental-swindling, dramatic farrago’, into which nineteenth-century opera had descended in the guise of Giacomo Meyerbeer and Parisian grand opéra.Footnote 12 For Wagner, drama must supplant opera as it actually existed, as mere theatre. Many of his successors, whether in opera or spoken theatre, agreed. By contrast, there lies at the centre of Hans-Thies Lehmann's widely accepted conception of postdramatic theatre a crucial reinstatement of the distinction between theatre and drama. Put simply: not all theatre is dramatic theatre. Even when postdramatic theatre might be considered once again as drama, it remains marked by the break. In Hegelian terms, we might call this ‘secondary’ dramatic theatre. If comparison with the modern and postmodern suggests itself, that should come as no surprise, for Lehmann's conception is rooted in that very distinction, not only with respect to use – or even abuse – of text but also with aesthetics of ‘space, time and the body’.Footnote 13

Theatre and drama, synonymous in much popular usage to the extent that ‘postdramatic theatre’ will sound a mere nonsensical provocation to many, had never stood in perfect harmony. However, a qualitatively new, modernist divergence, at least in spoken drama, is of importance here. Some playwrights, such as Luigi Pirandello, began to pride themselves on the unstageability of their works; some directors, such as Edward Gordon Craig, began to pride themselves on revealing the unstageability of dramatic works from the past, even as they staged and acted in them.Footnote 14 Brecht's epic theatrical distinction between what was represented and the mode of representation constituted a crucial mirroring of the disjunctures of reality, without ever abandoning the dramatic.Footnote 15 For Lehmann, writing in the late 1990s, much theatre in the wake of Brecht, often avowedly post-Brechtian, ‘brought with it a new multiform kind of theatrical discourse’, in part shaped by ‘the spread and then omnipresence of the media in everyday life since the 1970s’.Footnote 16 Such theatre was ‘precisely not a theatre that has nothing to do with Brecht but a theatre which knows that it is affected by the demands and questions for theatre that are sedimented in Brecht's work but can no longer accept Brecht's answers’.Footnote 17 With the ‘end of the “Gutenberg galaxy” and the advent of new technologies’, Lehmann wrote, ‘the written text and the book’ were ‘being called into question. The mode of perception is shifting: a simultaneous and multi-perspectival form of perceiving is replacing the linear-successive.’Footnote 18

That claim now seems both remarkably far-sighted and necessarily dated. There can be no denying the consequences of new technologies for perception and indeed artistic creation and performance, insofar as the latter two may now be distinguished; by the same token, a concomitant hunger for ‘liveness’, for the discipline and opportunity of immersion in, say, a Wagner drama has also in many respects grown. Likewise, texts have often reasserted themselves, in the theatre and via new, digital technologies. We can read, listen to and watch Wagner almost anywhere in the world, at any time: not necessarily even to the liking of a director such as Castorf, at least in the beginning. Reassertion of theatre and drama against passivity, against consumption, may or may not have been a necessary dialectical move; it would nevertheless be difficult to deny the artistic phenomenon. Certainly much recent and contemporary theatre has been interested in deconstructing ways of seeing and hearing in an age of mass media. Theatre, at any rate, as ‘a complex’, or at least a differently complex ‘system of signifiers’, was at the heart of what Lehmann proposed – doubtless in retrospect with exaggeration, yet hardly without cause – as a new dispensation, for him still greater than the caesura between Brecht and his predecessors.Footnote 19 Every text, even a performance text, might now be understood, after Roland Barthes, to pose the problem of its own possibility.

There is not space here, nor would it be particularly helpful, to begin to outline the implications of that shift; nor, indeed, to discuss the ways in which it might be considered unsatisfactory. However, briefly to say something of the challenges opera in general and Wagner in particular presented may be helpful. In some ways, opera might have experienced less of a problem than much literary drama from an attack upon or disregard for conventional literary narrative, though whether that would extend to Wagnerian drama is another question. Some operatic traditions had never placed such store on dramatic narrative in the first place and had always played fast and loose with notions of textual authority, be they verbal, musical or theatrical. It is probably no coincidence that early eighteenth-century opere serie with strikingly different dramaturgical concerns have experienced so strong a renaissance over a similar period, although many factors have been at play in that respect. If Bayreuth, its house lights dimmed, all eyes on stage, sought to emphasise dramatic and theatrical texts and single-minded audience communion, that signified reaction to alternative conventions.

The impossibility of ‘realising’ any drama, but perhaps especially any Romantic and modernist drama of note, onstage had, in a sense, always been recognised, though not perhaps by Wagner's widow, Cosima, who had sought, like Canute without the knowing irony, to hold back the tide of alternative stagings to the Master's. That the Master had known and grappled with that problem all along arguably, ironically, transformed Cosima-as-executor into the most unfaithful of all his would-be executants. Wagner had, to quote Patrick Carnegy, ‘wanted to establish a “fixed tradition” because he needed to defend his own imaginings against misunderstanding and perversion’.Footnote 20 Perpetuation of that ‘fixed tradition’ was ultimately to prove just such a misunderstanding and perversion. As ever in the idealist tradition, dialectics continued to multiply and to complicate.

Moreover, the Ring text, Wagner's conception of a festival theatre, and certain Bayreuth directors – if hardly the Bayreuth Festival as a whole – have worked, in the sense of Walter Benjamin at his most Brechtian, explicitly quoting Brecht's Umfunktionierung (functional transformation), towards ‘transformation of the forms and instruments of production’.Footnote 21 The dialectical approach, for Benjamin, had ‘absolutely no use for such rigid, isolated things as work, novel, book’, and, were this friend of Theodor Adorno not reluctant to engage with music he might have added, ‘for musical drama too’. Much the same might be said, we might also add, for its staging. Such an approach must instead ‘insert them into the living social contexts’. When, however,

a work was subjected to a materialist critique, it was customary to ask how this work stood vis-à-vis the social relations of production of its time. This is an important question, but also a very difficult one. Its answer is not always unambiguous. And I would like now to propose to you a more immediate question, a question that is somewhat more modest, somewhat less far-reaching, but that has, it seems to me, more chance of receiving an answer. Instead of asking, ‘What is the attitude of a work to the relations of production of its time? Does it accept them, is it reactionary? Or does it aim at overthrowing them, is it revolutionary?’ – instead of this question, or at any rate before it, I would like to propose another. … I would like to ask, ‘What is its position in them?’ This question directly concerns the function the work has within the literary relations of production of its time. It is concerned, in other words, directly with the literary technique of works.Footnote 22

The question is likewise concerned, we might further add, with techniques in all artworks and their staging, interpretation and more.

III

Enter Castorf, then, at Bayreuth for a new Ring in 2013: bicentenary of Wagner's birth and thus a year with greater expectations even than a ‘typical’ new-Ring year. After Chéreau and his unlamented naturalistic successor, Peter Hall (1983–6), the East German director Harry Kupfer had (1988–92) made something of a stir, albeit largely within the dramatic parameters of Chéreau and of Kupfer's other work. Otherwise, by the time of Castorf's enlistment, Bayreuth had gone two decades without a Ring receiving much in the way of either critical acclaim or controversy, so far as staging was concerned. Productions from Alfred Kirchner (1994–8), Jürgen Flimm (2000–4) and Tankred Dorst (2006–10, a late replacement for Lars von Trier) had come and gone. During the latter part of that period, its Parsifal stagings, led by Christoph Schlingensief (2004–7) and Stefan Herheim (2008–12), had garnered most renown. The latter swiftly achieved the status of a classic to rank alongside Wieland Wagner's; the former's reception proved more mixed and often downright negative.Footnote 23

Wim Wenders was first appointed to direct this new Ring; his withdrawal, echoing that of von Trier, was announced in April 2011. Unconfirmed rumours of Castorf's involvement first surfaced at the Festival opening in July of that year: very short notice for a Ring anywhere, let alone at Bayreuth, where the tetralogy is performed as one immediately, rather than in instalments.Footnote 24 This was not Castorf's first foray into opera; he had directed Otello at Basel as early as 1998. Operetta, in the guise of Die Fledermaus, had come a year earlier (1997) in Hamburg. He had also worked on Wolfgang Rihm's Jakob Lenz at the 2008 Wiener Festwochen. Other progenitors of sorts had been Die Nibelungen II – Born Bad, after Friedrich Hebbel, at the Berlin Volksbühne in 1995, and the aforementioned touring Meistersinger.

That said, directing a Ring, especially at such short notice, marked a step change, particularly given the Bayreuth necessity to present the musico-poetic text in its entirety, neither cut nor supplemented. Like Wotan, like Wagner – especially the Wagner of Bayreuth, compelled whether he liked it or no to deal with Ludwig II and Bavarian politics – Castorf necessarily knew more than a little about political accommodations. If Bayreuth were Wagner's Valhalla, would Castorf rebuild it or burn it to the ground? Would he enthrone Wagner–Wotan, a new god Siegfried–Castorf, or none at all, turning, like Chéreau, to those ‘men and women’, who, ‘moved to the very depths of their being’, remain at the end of Götterdämmerung? Such choices, perhaps not coincidentally, mirror Wagner's different attempts, as much superimposed on as supplanting one another, to complete the Ring.Footnote 25 Salvation, as Samuel Weber has observed, is ultimately to be found – might it also be lost? – ‘not in Wotan's “eternal work”’, that is Valhalla or Bayreuth, ‘but in … “masked revival”’, such as Castorf's or indeed any production, ‘as a self-consciously artificial, artifactual Gesamtkunstwerk. … Securing the sacrality of the stage … demands a structure that both situates and protects it. In this way the ties between Wotan and Valhalla mirror those between Wagner and the Bayreuth Festspielhaus – as the material and specific location of each individual performance.’Footnote 26

On the face of it, the imperative to produce the Ring in full might be considered a backward turn for Castorf to something approaching ‘conventional’ Regietheater, a further accommodation such as the post-revolutionary Wagner had struck both with tendencies within himself and in a world that had failed to turn in the way he and other 48ers had hoped and expected. Should we accept Risi's typology as outlined earlier – there are well-founded pragmatic–analytical reasons for doing so – this would represent an unaccustomed third way, willing or otherwise, for the anarchistic Castorf, who had long been accustomed to greater scope for interventions. Dialectically, however, that need not be the case. The modernist may reassert itself in the postmodernist and the dramatic may reassert itself in the postdramatic, as Lehmann has always insisted.

Similarly, the text will often find a way to reassert itself, to challenge its deconstruction; there is more than one way both to deconstruct and to (re)construct. Before, however, we turn to Castorf's confrontation and compromise with Wagner, we should look at what is meant by dramatic and postdramatic and at how they might relate to Castorf's work and reputation. Definition, alas, is no help here. No more than, say, with romanticism or modernism can we assemble a checklist; at best, we can point to tendencies in the historical movement. Perhaps, however, Hugh Honour's oft-quoted claim that the Romantics were ‘united only at their point of departure’ will prove of use in considering those working in postdramatic theatre, Castorf included.Footnote 27

IV

Even prior to reunification, Castorf had shown little in common with East German directors such as Herz and Kupfer (mentioned previously). Castorf came from a different generation from either and had no evident interest in opera. He was viewed with suspicion by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) authorities. His 1981 production of Othello at the Theater Anklam, his first staging as senior director, played in semi-darkness, dialogue apparently reduced to barely audible mutterings in English, and was condemned in Stasi reports as equally offensive ‘to Shakespeare and to the public’, undermining ‘socialist cultural politics’ by emphasising ‘the impossibility of communication along with a blighted view of humanity’.Footnote 28 When Castorf took charge of the Volksbühne in 1992, it was very much as an East German, though not necessarily as would have been expected. Castorf, Siegfried Wilzopolski has argued, does not see theatre as a means of solving problems; rather, it ‘amplifies problems and destroys every alternative’ – which may, yet perhaps need not, suggest nihilism of some variety. Instead of resolving contradictions, Wilzopolski continues, Castorf's theatre ‘intensifies them beyond acceptable limits.’Footnote 29 Political order sets rules, whereas theatre provides exceptions: disorder, shading at least into chaos.

Castorf has shown no theatrical interest in purveying the dubious wares of Ostalgie, of nostalgia for the old ‘East’. Asked whether he missed the GDR, he answered scornfully that it had perished quite logically, ‘in its own decadence’.Footnote 30 That was one of his more polite responses. On the other hand, when moving to his office on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Castorf hung a large portrait of Stalin on the wall and (Brandon Woolf tells us) erected ‘three massive letters – “OST” – at the building's highest point, perched prominently for the whole town to see, and to encourage – or demand – that a new (re)public engage the many associations that word might evoke. “The Volksbühne is important because it is a GDR institution that survived,” Castorf explained. “But we do something that the GDR, as a state, did not do.”’Footnote 31 The question was as much what it meant to operate a public theatre, ensemble included, in this new society, founded upon the ruins and something approaching the conquest of the old, and Castorf's (East Berlin) Volksbühne proved arguably to be the locus for such discussion. ‘Each play’, Castorf claimed, in his opening season, ‘could be reread from the perspective of … immanent “left critique of a left Utopia.”’Footnote 32 The Volksbühne's work, Lehmann noted, was ‘surrounded by an atmosphere of politicized discussion and formations of like-minded people’. He cited a Castorf programme note's claim that it was ‘a special characteristic of artists from the former GDR, unlike their West European postmodern counterparts, that they considered themselves, “however ironically”, as “failed politicians” making a contribution to ideology.’Footnote 33 Stalin would return, as we shall see, on stage at Bayreuth; so too, essentially, would the rest of this and, more importantly, the reasons, albeit transformed by the passage of two decades, for having put him and ‘East’, with its multiplicity of meanings, on show. His Ring should not be reduced to an attempt to present ‘Ost-Theater’ to the West, but it may partly be understood to have been doing that and to have been enriched by the attempt.

Perhaps the time was right for Castorf as well as for Bayreuth. Critical voices, as is their wont, were beginning to ask whether his best years were now behind him, though that had already happened before: on his appointment to the Volksbühne in 1992, many thought it too late in the day, declaring that the political importance of his work in Karl-Marx-Stadt and Anklam could not be repeated.Footnote 34 (It could not, of course – any more than Wagner could repeat Lohengrin in the Ring, as opposed to responding to the questions it had failed to resolve and to those of a new, post-revolutionary age.) A 2000 doctoral thesis expressed scepticism with respect to envisaging ‘a new chapter in Castorf s theatrical career’. Oddly, the author, Katya Bargna, noted that ‘rumours of an opera debut in Basel (with Verdi's Otello) have been silenced’ – it had by then taken place – and asserted that Castorf's ‘brief interlude with operetta remained strongly anchored in the “theatrical” rather than the “musical”’.Footnote 35 It is interesting, though, to note the prescience with which Bargna imagined that this new chapter might involve opera and an anchoring in ‘the “musical”’, for which we might partly understand the demands of that musical dramaturgy proposed previously by Clemens Risi: a turn, broadly conceived, towards ‘Regietheater in opera’. Acknowledging both the high stakes and the specific nature of operatic collaboration, Castorf declared that if what he, with set designer Aleksandar Denić and conductor Kirill Petrenko, had formulated did not show the ‘explosive power’ of Chéreau's Ring (which he had not seen, even on video, yet knew by reputation), it would have ‘failed’.Footnote 36

Description and analysis of a stage production will always involve compromise and approximation. Even were one to have seen and somehow taken in everything from each of its performances, how then to mould that material, along (perhaps) with director's notes, broader context and so on, into a single account? Should one even try? In practical terms, what one can do is state which versions one saw – in this case, I saw performances of Castorf's Ring in 2014, 2016 and 2017 – and steer a course between organisation of one's observations as a whole and highlighting of important developments. That difficulty – arguably, also opportunity – is compounded for a production running over several years, in this case five years from 2013 to 2017 inclusive, during which changes were made to the production as part of Bayreuth's Werkstatt principle – and not, it seemed, always at the director's behest. ‘I can say many positive things about over the past year’, Castorf remarked in an interview prior to the first, 2014 revival: ‘Aleksandar Denić and I had only a little time for our Ring-concept. There was great pressure, because … Wim Wenders … had cancelled late. This pressure, as is often the case in politically and socially revolutionary situations, generated a certain liberality. There suddenly came into being, as in Cairo’, during the Arab Spring, ‘a remarkable revolutionary atmosphere. The rulers abdicated, because they had no choice. Then they stood with their backs to the wall. However, that is all over now. Now they try to roll it back.’Footnote 37 So continued the struggle – with Wagner, with the gods of Bayreuth and the Wagner family, with the post-Wende dispensation: intersecting dramas and theatre of their own.

The following outline and analysis of my own responses will necessarily be written from a highly subjective standpoint. That will arguably be the case for engagement with any theatre, indeed any artwork; it is the more extremely or remarkably so with postdramatic theatre such as this, confounding expectations with seeming intention and disregard. Is the attempt to make sense, to interpret, doomed? Perhaps; yet, like attempts at political and aesthetic revolution and at so many other things, that does not mean we wish to avoid it or are able to do so. I have decided to present my own responses, formed not in a vacuum but in dialogue with the world around me, rather than to consider explicitly those of others, whether in newspapers, online criticism, or elsewhere. That is not to dismiss other standpoints (far from it), nor to claim that they have had no impact upon me, but rather to attempt to retain focus within the necessary bounds of an essay.

V

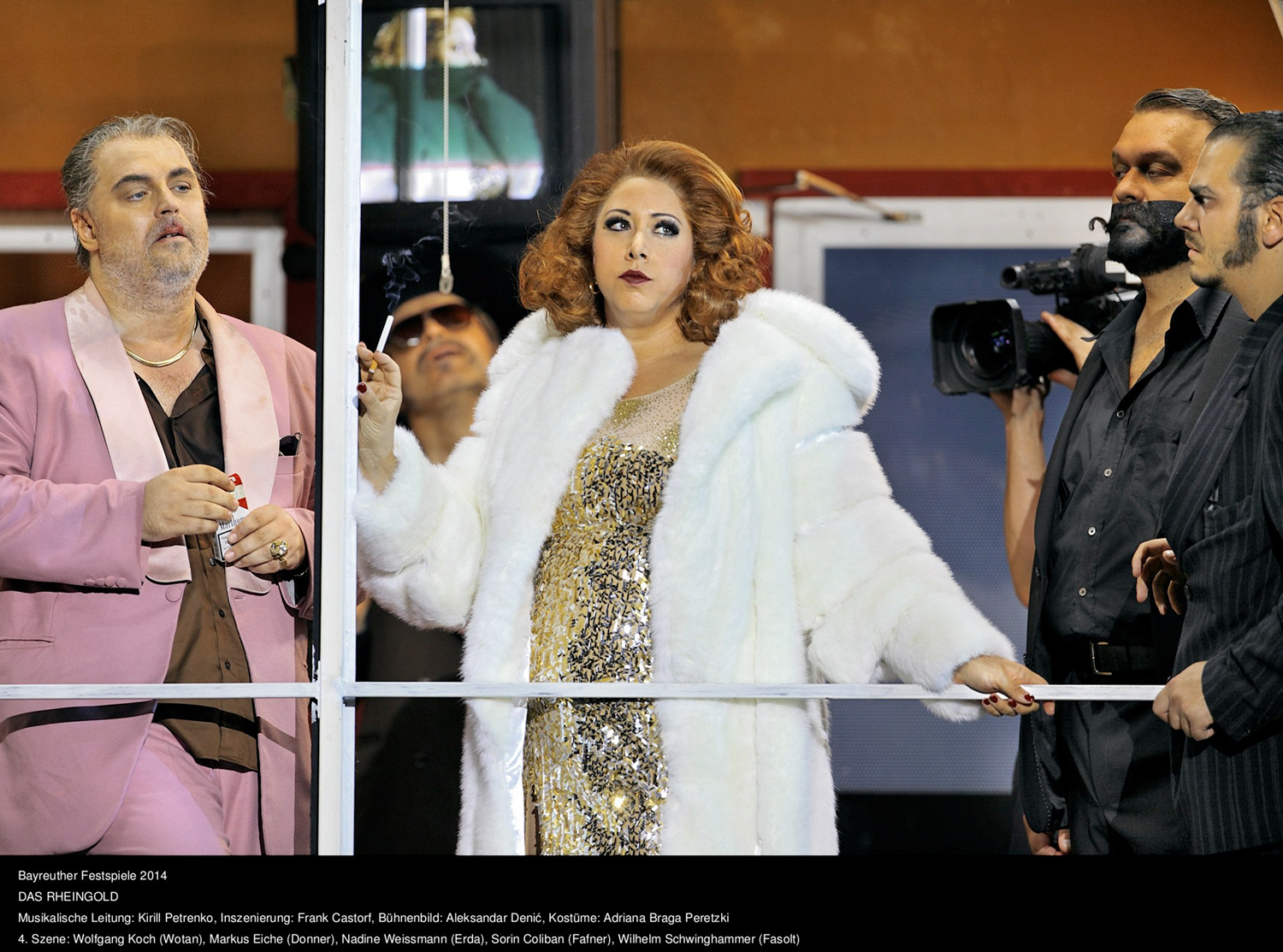

Where, then, to start with the staging itself? It is Wagner's question as well as Castorf's – and that of this article. The Ring, like the Bible, is noteworthy for presenting two Creation myths, which may or may not be entirely compatible: one at the opening of Das Rheingold; one, told in the retrospect of epic narration, in the Norns' Scene of Götterdämmerung. Wagner's idealism nonetheless adheres to conventional chronological ordering. Castorf's notably did not. Here, Das Rheingold, the work from the epic past of the Eddas, stood separately, in the present. It was, however, a different present, in geographical, narrative and ‘real’ senses, from that of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, which may be understood to follow on from Die Walküre, albeit with a gap of more than the traditionally understood generation. Castorf's Rheingold was set at the Golden Motel on the Texan Route 66 (seen in Figure 1). It brought oil, trickling as gold throughout this Ring, to the fore; yet it also stood separate, both acknowledging its separation in Wagner's tetralogy – the age of gods, as opposed to heroes and/or humans – and pressing disjuncture beyond anything intended by or even conceivable to its creator.

Figure 1. Das Rheingold, dir. Frank Castorf, 2014 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

As Lehmann has noted of Shakespeare's rejection of much in Aristotle, such as the demand for the right ‘magnitude’ of tragedy, this anticipates the postdramatic:

The impression of an open world without borders … is nearly always present in Shakespeare's theatre. Empires of thought and matter – wide and inexhaustible, endless in their various aspects, from those encompassing the world to the most banal – are travelled by this theatre with the breath of Welt-Zeit, back and forth, between fairy tales and reality, dream and triviality, the cosmos and the inn, between Lear and Falstaff, the sublime and the inebriated, tragic and comic.Footnote 38

Taken a step or several further: do we need or want any grand narrative – Hegel's or Marx's, say, as much as Wagner's – to cohere? Irrespective of the answer, should we not ask the question of these drama(s) in Wagner's own theatre? Relating to the world, to different worlds even, is not necessarily the same as representing it or them as whole(s). However, the world of Das Rheingold, if not necessarily its relationship to the world(s) of the remaining Ring operas, seemed self-contained, manageable – and, as we shall see, ‘managed’. Perhaps that is why, even among the disgruntled, this production received at least grudging praise from all but the most irreconcilably werktreu of audience members. Back then, or perhaps forward, to the Golden Motel: a staging post, as motels are, reflective of wherever it is that Wagner's gods find themselves prior to entry into Valhalla.

As is typical of Castorf's work, much was presented in video projection. Some, as we see in Figure 2, was filmed live. Some was not, immediately granting the privilege, curse, and/or illusion of further information – as a production may elect to ‘reflect’ or further to dramatise the work, to undercut it, or to do something else entirely. A screen at the top of the motel relayed events elsewhere – including to the audience – some of which replicated what one could see on stage either readily or with difficulty, some of which would otherwise have remained unseen, unknown. There were stills too; where had they come from? Did those events, those scenes, happen at all? Hyperreality and its complicated relationship to overabundance already questioned, faded quality and distorted colour to the film further suggested that all was not as it seemed. Discrepancies on- and offstage seemed to creep in, whether by design or the spectator's own unreliable narration. The contemporary representational difficulty of why the image tends to seduce the spectator more than the ‘real’ – ‘the electronic image lacks lack’ – was of the essence.Footnote 39 Just how many narratives or standpoints on narratives could we see, let alone take in, simultaneously? It was no good throwing up one's hands in despair, and saying just the one: the world inside or outside did not work like that anymore; it probably never had. One might sometimes be relatively certain concerning discrepancies: people present on film who were not on stage in what one could see being filmed. At other times, one did not and, given the mass of information, could not know. Fricka underwent brief, mediatised reinvention as a ‘blonde’ of a variety favoured by a pleasure-seeking yet ruthless, playboy Wotan – both sisters, Fricka and Freia, his bed-partners – as by politicians such as Donald Trump in their own ‘reality’ shows. That world of ‘entertainment’ was never distant: we participated, however great the discomfort, whilst we disdained. That prepared the way, partly through affinity, partly through shocking contrast, for the moment of greatest dramatic power, in which, far from coincidentally, Castorf proved entirely ‘faithful’ to Wagner, the motel bed stripped to its frame, a PVC-clad Freia hidden from view by golden bars. Filming and voyeurism rendered its simplicity all the more sickening.

Figure 2. Das Rheingold, dir. Frank Castorf, 2014 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

Theoretically, one might have looked away, but it is difficult to imagine having done so. In a letter to Schiller, Goethe complained of people far too often wanting to see a novel onstage as soon as they had read it – ‘how many bad plays have arisen!’ – and likewise to see illustrations from the novel, ‘etched in copper’. It was all part of an audience desire, to which modern artists all too readily conceded, to ‘find everything completely true’, to understand everything as ‘perfectly present, dramatic’.Footnote 40 When cameras were positioned all around me (as, say, one of the Rheingold gods), or when, in the audience, I watched those cameras and their creations as well as the ‘original’ performance and the original text, I was led both to observe the situation and to engage in Goethe's critique; perhaps, even, to engage in critique of Goethe's critique, and so forth. Multiplication of media had both broadened the possibilities here and dulled our awareness: doubtless part of the reason for heightening our awareness in an explicitly aesthetic situation.

A keen student of Ludwig Feuerbach's humanism, Wagner saw human beings reduce themselves by transferring their best qualities to a being external to themselves: first God and/or the gods, then the state, capital, even the delusions of ‘love’. Such images and our consumption of them offered, knowingly or otherwise, a neo-Feuerbachian inversion for our age; as befitted a post-Adornian, administered world, dialectics were unremittingly negative. At first glance, like much of the mass culture it depicted, the production may have seemed to be all about sex and concomitant exploitation. One might say the same about Wagner's first scene ‘itself’ from the standpoint of what Wagner called Alberich's liebesgelüste (‘erotic urge’) towards the Rhinemaidens.Footnote 41 Wagner remarked that he had ‘once felt every sympathy for Alberich’; in his turn against the Rhinemaidens, Alberich represented ‘the ugly person's longing for beauty’.Footnote 42 In work and staging alike – a crucial coming together – there had been no golden age; this, one of the most tenacious and perhaps necessary of myths, had been fatally undermined by an ‘ugly’ man rejected by Rhinemaiden hedonists from a ‘beautiful’ world, their antics filmed for our consumption. Delights may have been won from the ‘Rhine’ waters, yet those waters, a mere paddling pool, had, like the electronic image, no depth; they too lacked lack. Once absent from Wagner's stage, the ‘girls’ continued to be part of Castorf's, of ours. Alberich's rejection was repeated in their dismissal of an Everyman figure, who appeared in different guises through this Ring's entirety. Played by Castorf's assistant and dramaturge, Patric Seibert, he was in this case a member of staff, serving cocktails to the girls in their hotel room. He wished to become part of their narrative, or rather would like to welcome them into his; instead, they thrust a ‘Do not disturb’ sign in his face. There was a hint here of the introduction of a ‘real’ person into the drama, albeit one who was not actually real at all: we might call it unreal reality theatre.

Rhinegold reimagined as oil powered all of what we saw: forecourt petrol pumps; the material of American popular culture; the motel's final-scene ‘rainbow’ rebranding; even, perhaps, something narcotic, when Donner's mysterious ‘clearing’ of the air left pleasure-seekers in the motel bar in a state of trance-like animation, eye close-ups leaving the spectator in little doubt that something stronger than alcohol was being served. After all, every character claimed to see a rainbow, even to walk upon it, in order to reach somewhere they stood already. Perhaps the same might be said, in Feuerbachian manner, of the illusory sacerdotal fortress of Valhalla in the Ring ‘itself’. Inclusivity signalled a definite step forward for contemporary mores: in the pool and in the bar, Rhineboyz joining our ‘fun-loving girls’.

Freia's ransom from the giants took place, yet almost as an afterthought, everyone – even she – having lost interest. There were too many other narratives to write, to watch, to consume. Freia's golden apples, for which we should read stereotypical female ‘assets’, had in any case passed their sell-by date for Wotan, now that a fur-clad, televisual Erda, knowingly trashy in Nadine Weissmann's moving performances, had made her melodramatic entrance, delivered her ‘character's’ lines and submitted to Wotan in the shower cubicle. Privacy of a sort was permitted for rape: no filming allowed. It operated, however, solely on behalf of the rapist.

VI

Just as the opening of that Rheingold presented a place of transience, so did the close. The gods could not be immortal, for we were all, like Marx and Wagner, students of Feuerbach now. On moving to a different world for the rest of the Ring, we were bidden to reflect on the widely, if far from universally, accepted impermanence of capitalism, a claim regarded strictly as the province of the ‘extreme’ Left during the age of liberal triumphalism extending from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the 2008 financial crash.

Marx, then, was back, as Derrida had always insisted.Footnote 43 At first, however, his – and socialism's – presence were understated, at most implicit. For Die Walküre, we moved, as visual clues gradually informed us, to Stalinist Azerbaijan in 1942 (see Figure 3): an agrarian, yet industrialising, society, in which Denić's set transformed Hunding's traditional house into an oil well. This was a society in which all, Wotan included, hoped to discover the oil that powered the rest of the cycle, both inciting and frustrating revolutionary hopes. Fricka now came armed with a whip of conjugal enforcement. An initially bookish Seibert (Everyman, assistant director) seemingly willingly – yet driven by what compulsion? – took the caged place of farmyard fowl; was animalised; and, following rescue, transformed by the experience, reinvented himself as businessman once oil had been hit. All this took place against the new score's more ‘Romantic’ canvas, vocally and orchestrally heightening the force of Castorf's and Wagner's contradictions.

Figure 3. Die Walküre, dir. Frank Castorf, 2014 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

Rheingold had theoretically taken place later in time, yet Castorf's disjuncture paradoxically, even dialectically, rendered Rheingold all the more distant as pre- and/or alternative-history. It invited one to think about time – for Thomas Mann, ‘the unit of narration, as it is the unit of life … [and] “of music”’ – rather than passively accepting conventional chronology.Footnote 44 Dramatic theatre's concern with structuring of time had been somewhat undermined, or at least transformed, by Brecht, even by Chekhov; something similar had taken place in some twentieth-century opera; for instance, Luigi Nono's Al gran sole carico d'amore and Prometeo. To impose such a disjuncture, to make the audience ask what, if any, the connection might be, was to invite one to ask both what Wagner was doing and why. His Rheingold world of gods and giants is not identical to that of the succeeding three dramas, although there is, of course, much complex interconnection and interaction. We see in it, at least to a certain extent, where things might lead.

In Castorf's staging, however, we were now set on a different historical and ideological trajectory, one set in the Eastern bloc, as many – not those who lived under ‘actually existing socialism’ – had once called it. Perhaps we were giving socialists such as Wagner and Marx a try after all, permitting thoughtful rather than unheeding deconstruction. If the neoliberal world of the Golden Motel were so rotten, what alternatives might there have been? Angela Merkel's grim, neoliberal claim that not only her government's but also any government's actions were now ‘alternativlos’ hung over proceedings, ready to be dispelled by Donner's hammer like those Rheingold mists, albeit without that ever happening.Footnote 45

Video showed, to widespread initial bewilderment, Russian and Azerbaijani scripts, an issue of Pravda, even hints at socialist realism – as well as other (purposely?) strange images, such as a woman eating a cake and a local patriarch drinking shots of vodka and making telephone calls. There was assimilation, then, as Soviet ‘progress’ confronted Central Asian Baku. It eventually transpired that the patriarch may have been Wotan; there was certainly similarity to the god as revealed on stage. Yet it was never certain whether similarity had shaded into identity, unreliable, mediatised narration again to the fore. The gods’ return to a new, older, alternative world proved intriguingly consonant with ancient mythological conceptions. Adopting local dress, customs, commercial practices, indeed leading the latter, they did what they have always done when assuming human form. Wotan's loss of his ‘local’ beard, seen first on film when drinking vodka, transgressed and inverted the ancient dramatic taboo of dropping his mask: Wotan-as-actor revealed as the real character.Footnote 46 At last, we beheld him, like Hunding facing his death, in all his godlike terror. I also recalled with Wagner, student of Feuerbach, that human beings had made these gods, as we also had others, more abstract, such as capital, law and ‘love’.

For a modern audience, one might say the same of Wagner and romanticism. Here, the production fared less well, at least on the surface, though this might have been read as commentary on the relationship between the decline, even death, of character and other (postmodern?) forms of subjectivity.Footnote 47 It certainly had something in common with a postdramatic move against the ‘depth’ of speaking – in this case, singing – figures.Footnote 48 Wotan's delivery of his second-act monologue was, presumably on purpose, stationary, even un-directed: not only deconstruction of the plethora of action in Castorf's Rheingold, but a contemptuous reinstatement of ‘opera’. Film enabled close-ups of Sieglinde's exaggerated, ‘operatic’ expressions when preparing Hunding's potion. Fricka's ‘mad’ behaviour witnessed in Figure 4 was again conventionally, even pejoratively, ‘operatic’. It stood in stark contrast with the alternative yet related tradition of Wotan merely standing and delivering: ‘park and bark’. However, once the non-Brünnhilde Valkyries had departed the scene, diminishing returns set in for the rest of the third act. The Lenz of Volsung love and Siegmund's rejection of Valhalla having passed without scenic notice, so too did the relationship between Wotan and Brünnhilde. Refusing and failing to listen to each other made an important point, yet ‘real’ action continued to lie with oil strikes, not Siegmund and Sieglinde. This was less, it seemed, a Brechtian strategy of alienation than mere impatience, with obscure (post)dramatic results.

Figure 4. Die Walküre, dir. Frank Castorf, 2017 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

VII

It was important, however, to be reminded on film that Hitler was also in pursuit of Azerbaijani oilfields. Stalin's victory and the failure of Operation Edelweiss in the wake of Stalingrad implicitly prepared the way for the world(s) of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung. Castorf and Denić – the latter's spectacular set designs arguably as important as much of the action – took us to an alternative present day (to ours and/or Das Rheingold's). What if the Wende had not come, if the ‘West’ had not won, or if that victory, such as it was, had taken different form?

Siegfried revolved between two sets, clearly intended, at least in part, as two sides of the same societal coin, whether synchronic or diachronic; we may recall Lehmann's observation about Shakespeare's worlds. Pressing vulnerable Left buttons concerning quite how far one might go with historical socialism, Figure 5's alternative Mount Rushmore – Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao – provided a backdrop both to the caravan and to pursuit of the ring Mime had inherited from Alberich (not that the latter had given up). On the other side, as seen in Figure 6, lay a magnificent recreation, a simulacrum convincing both in fidelity and infidelity – Regietheater itself conceptually staged? – of (East) Berlin's (Al)exanderplatz: S-Bahn and U-Bahn stations, World Clock, post office, fountain and invented-yet-real restaurant.Footnote 49 The sheer scale of both sets, not just as stage objects (although certainly including that) but also in terms of conceptual reference and possibility, created to an extent I had not hitherto experienced a sense of awe at the epic quality of Siegfried's drama, and epic literary traditions more generally, albeit highly mediated.

Figure 5. Siegfried, dir. Frank Castorf, 2017 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

Figure 6. Siegfried, dir. Frank Castorf, 2017 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

Was this ‘Domesticating Wagner’, as Michael Tanner entitled a chapter on Wagner staging from Chéreau onward?Footnote 50 Far from it. Given Castorf's evident impatience with the romanticism of Die Walküre, it was intriguing to see the fairytale of the boy who learns fear receive such a probing and, in many respects, sympathetic treatment. There was no doubting the distance that had been travelled by the close, nor the genuine, neo-Feuerbachian, revolutionary hope felt on occasion, especially at the ends of the second and third acts. Hope was not unalloyed at either of those points; nor is it in Wagner's drama, the nihilistic ecstasy of the words to Siegfried and Brünnhilde's duet combining in highly disconcerting, double-contrapuntal – that is, counterpoint in the score, but also counterpoint between words and music – virtuosity. The production nonetheless celebrated with an uncanny second affinity, to borrow again from Hegel, the particular character of Siegfried as the Ring's ‘scherzo’: as complex an idea after Beethoven as after the post-Dresden uprising in 1849 or after the Leipzig uprising in 1989.

Liminality is an idea crucial to the drama, to the epic tradition in which it stands, and perhaps also to realisation in performance. Of particular importance is the liminal status, with concomitant dangers and emancipatory potential, of the forest in which Siegfried takes place. That may be in turn related to the interest of many Germany Romantics in the Roman officer turned Germanic chieftain, Arminius or ‘Hermann’ (a speculative Teutonisation), who from the Teutoburger Wald had halted Roman advances into Germania. ‘Assuredly he was the deliverer of Germany’, the admiring Tacitus had recorded in his Annals. Arminius ‘had defied Rome, not in her early rise, as other kings and generals, but in the height of her empire's glory.’Footnote 51 Wagner too rejoiced in the memory of those events, even when telling Cosima in rather gloomy terms: ‘So far, we have been great in defence, dispelling alien elements which we could not assimilate; the Teutoburger Wald was a rejection of the Roman influence, the Reformation also a rejection, our great literature a rejection of the influence of the French; the only positive thing so far has been our music – Beethoven.’Footnote 52 Hence perhaps this post-Beethoven scherzo? The implication was that things would, at least might, change, although by then (1872) the strong, pessimistic-Schopenhauerian element in Wagner's rereading and rethinking of the Ring suggested resignation. Enter the resigned Wanderer, a more fitting hero for a frustrated revolutionary age than the rebel Siegfried, born in that forest, whatever the hopes invested in him.

At an immediate, scenic level, in Castorf's production the revolving stage did its work. Was this a forest, albeit a distinctly dried-out version, or an urban interchange? It seemed imbued with transience, possibility and implicit potential for thwarting revolutionary potential. East Berlin seemed at least on first acquaintance to be going well enough. But was it actually East Berlin at all? One may have responded, not entirely without reason: ‘it is what it is’, just as Castorf's new ‘OST’ at the Volksbühne was what it was, or the mysterious (Al)exanderplatz crocodiles, increasing by one in number each year of the production. Their sheer absurdity exerted a power of its own: in and of itself, but also over Bayreuth, Valhalla, Wagner, romanticism, revolution, post-revolutionary drabness, over anything and everything, stage action included.

Even if there were no explanation, such riddles seemed designed to make us seek one: like Mime, though, perhaps we never asked the questions we needed answered. More nihilistically, perhaps there were no such answers, even questions. Images of what seemed to be political leaders speaking came and went on video screens above: was that Siegfried? Mime? The Wanderer? Or were they just faces of no one in particular, onto whom we (literally) projected what we expect, desired, or had been led to believe? Projections fused with the figures on the mountain, heightening the old friend of unreliable, now frankly historical, narration. What did it mean to see Siegfried's face projected not onto revolutionary Lenin or even Mao but ‘establishment’ Stalin; and Wotan, his eye damaged, yet playfully winking, onto Stalin's? Perhaps nothing at all; it was arguably up to a dazed audience in an apparently post-revolutionary age to create meaning, or not. On the other hand, as Lehmann suggests in the brief epilogue to Postdramatic Theatre, ‘the politics of theatre is the politics of perception’.Footnote 53 Gods and heroes alike – continued to take on new, often disconcerting form. It was difficult to resist Beckettian gloom. Revolutions from Wagner's in 1848–9 – further back to the French Revolution too – to those of 1917–18, 1945–9, 1989 and so on, even perhaps 1933, had all failed in their respective ways. ‘Revolution’, for historians such as Reinhart Koselleck a Grundbegriff or ‘fundamental concept’ of modern socio-political vocabulary, seemed fundamental above all in its recurrent failure.Footnote 54 Our alleged supposed revolutionary hero, Siegfried, proved as brutal as any, his Brezhnev era, Afghan War (a post-9/11 world knew only too well where that would lead) Kalashnikov, heard to terrifyingly loud effect in the theatre in the killing of Fafner. Meanwhile, oil continued to do its work. Seibert, initially Siegfried's chained bear, found himself covered by it.

Wotan's rejection of Erda at the station restaurant proved a dramatic focal point, Seibert's Everyman waiting on the unhappy, unequal couple. During the third-act Prelude, Erda on film offered a varied reprise of some of her Rheingold actions – not unlike one of Wagner's famous narrations (in which we learn more about previous acts and from different standpoints), or the narrative thrust of that Prelude itself, in which Wotan finally resolves to dismiss Fate.Footnote 55 Having worried with her assistant about which wig to wear, she made a last-minute substitution to the god's favoured blonde in preparation for her final encounter, her final appearance on stage (or anywhere else). Once again, Wotan treated the earth goddess just as he would any other woman. Having had her fellate him, he contemptuously slipped her some banknotes and ran after Siegfried, leaving her to settle the bill. Unafraid to sound, as well as look, hurt, damaged and cowed, Weissmann cut a movingly pathetic figure under the table at her last hurrah, all the more so for a resolute lack of sentimentality.

Brünnhilde seemed unlikely to fare any better once woken by her ‘hero’. As she donned her wedding dress – a signal, like the ring, that she would believe in ‘marriage’ to Siegfried until the end – we knew already that he would betray her, as we knew he would the revolution itself. Initially, he cruelly abandoned her even as they and the orchestra sang of their union, opting instead to possess a Woodbird straight out of the Rio Carnival. In 2017, however, in an inversion of previous years’ action, Siegfried returned to Brünnhilde and they ‘traditionally’ embraced. The year 2016 offered a mid-point, in which Brünnhilde separated Siegfried and the Woodbird; having taken control, she then embraced her lover. Was Castorf reconciling himself to Wagner, to the Romanticism of the forest whose liminality we saw and felt but whose trees, whose green, whose Caspar David Friedrich depths, we may have sensed only in the orchestra? Perhaps the Bayreuth audience now needed to deconstruct the ‘Castorf Ring’, which, like Wagner's, it knew too well; perhaps Castorf did too. Either way, we, the director included, were asked difficult questions about female agency and violence towards women onstage. Brünnhilde, no longer a victim, would live to fight another day.

VIII

That day would be Götterdämmerung, so no one, least of all she, should have felt unduly optimistic. There was no lack of apocalyptic atmosphere to the grand denouement. Denić's set designs, Adriana Braga Peretski's costumes and Rainer Casper's gloomy lighting worked with, even intensified, Wagner's world-weary E flat minor opening chords. Exhaustion in a well-nigh Beckettian sense ruled: Fin de partie? The Norns’ Scene struck what was in many ways a highly faithful note of extravagance and vagrancy, of Fate and street gossip, as they made their way across the stage to a peculiar little shrine, almost Marian, yet clearly anything but, whose function remained mysterious in apparent Beckettian meaninglessness. It both attracted and repelled – like Wagner, one might say, like the production ‘itself’. Not only the Norns but also many of their successors, Wagner's characters and Castorf's additions, would continue to enter it and, perhaps just as important, continue to attempt to leave it. Replete with plastic refuse, born of the oil that had run through the tetralogy, it suggested exhausted consumerism and a related, deadly, contemporary far-Right politics, which, as a poster declared, preferred ‘Oma’ (grandma) to ‘Roma’. There were also glimpses of an eternally televised non-revolution identical with all late capitalist lives: witnessed in Andreas Deinert's and Jens Crull's video footage, both on a particular television screen within the shrine and on larger screens elsewhere onstage. East and West both led here: state capitalism, for that was what it had always been, as well as neoliberalism. There was no escape. Hopes for an alternative historical path had ended up precisely where ‘reality’ had, with nationalist-racist movements such as the Alternative für Deutschland and Pegida, nowhere stronger than in the (East German) Saxony in which Wagner had been born and had grown up. The world will always have changed during revival, reinvention, restaging – whatever we wish to call it – of productions, but it did so in particularly notable ways from 2013 to 2017: the ‘refugee crisis’, the rise of far-Right ‘populist’ movements and so on. Certain horrors and moments of reflection sharpened in focus, again as they had for Wagner in the post-revolutionary reaction of the 1850s.

It seemed, then, that the end of this Ring's world was truly nigh, though even that ‘hope’ would be frustrated. Writing on Chéreau's production for a Bayreuth programme note, Günter Metken had described Valhalla as ‘no longer the undamaged place it once was’, with ‘something of the unhealthy air of Venice … It is one of those choice apparitions of death conjured up by the previous [nineteenth] century, in order to repress the rapacity of daily life.’ He proceeded to liken the entry of the gods into Valhalla – like Castorf's Golden Motel, by now another world – to a tableau vivant of Bruegel's Parable of the Blind.Footnote 56 Those words seemed also rather well to fit both this Götterdämmerung, and its relationship to Chéreau and Wagner alike. For Castorf's Götterdämmerung was a world that could be read, intentionally or otherwise, as having taken its leave also from Chéreau's: a world of rituals in a post-religious society that knew no morality, found it impossible even to ‘know’.Footnote 57 Yet still, in this nihilist hell, its characters must continue to do something; the second act – Wagner's, Chéreau's and now Castorf's – continued to offer up desperate, pointless evocations to gods long since deceased.

That had been presaged at the opening, when we saw Castorf's Norns dressed up for a ball to which they knew they were neither invited nor capable of attending. Yet what else was there to do? They could sing, and did – not that it made any (dramatic) difference. Likewise Siegfried showed himself no better than any of the previous leaders we had seen, his elevation clear from demeanour, costume and further ‘political’ speech. Wotan may have dismissed Erda as Fate, but what did and could that mean here? Not very much in a world in which perpetual rule by petrochemical works and Wall Street seems inevitable. That the former was an East German factory whose slogan, ‘Plaste und Elaste aus Schkopau’ (‘Plastics and Elastics from Schkopau’), was a long running joke for Westerners with respect to poverty of aspiration and achievement, heightened the sense both of capital's adaptive grip and its ultimate absurdity. From the Western Rhine to the Eastern Elbe – the sign used to be seen from the motorway on the bridge over the Elbe near Vockerode – even the most backward state enterprise could, like Rheingold's Golden Motel, be rebranded and yet remain the same.Footnote 58 Privatisation works, according to the covert logic of neoliberalism, if not its overt ideological claims of progress. All the while, a New York Stock Exchange carelessly concealed in cloth awaited its deliberately underwhelming revelation (and would-be revolution).

The second act was thus set for another attempt at revolution that failed, as a mediatised rerun both like and unlike that which had had Wagner flee into Swiss exile. At least something had happened then. There was much of the nihilism of post-crash ‘anti-capitalist’ protestors here, neither knowing nor caring what they want, save for attention. There certainly seemed to be real crisis here, real hunger, Seibert's fast-food van failing to cope with demand. Or was that just another illusion, another ‘drama’ in a postdramatic age, in which members of the crowd held placards announcing crisis and hunger, in some cases acted as if their lives were at stake during pillaging, then perhaps returned home afterwards to watch it all on another screen? ‘The people’ had not, hitherto, been entirely absent from this Ring. Their inclusion, not only in the person of Seibert's character(s) but also on video (a community in Die Walküre's Azerbaijan, for instance), and its collision with a world of cruel gods, dwarves, heroes and so on had throughout proved an important device not only of ‘reality’ but also of dramatic interaction between those ‘kinds’ of being Wotan's strategy had always been to keep apart. They were nevertheless far more present here; such, after all, is the nature of the work, in which the grand opéra chorus is reinstated, aufgehoben (i.e., in Hegelian terms, its negation negated).

In one sense the question posed by this Götterdämmerung seemed classically Marxist and, more broadly, socialist. In a world of abundance, the genuine achievement of the bourgeois mode of production was, to quote Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto, to have been ‘the first to show what man's activity can bring about. It has accomplished miracles surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals; it has conducted expeditions that put in the shade all former Exoduses of nations and crusades’ – how to achieve redistribution?Footnote 59 Hence the importance of food as a visual motif in Castorf's production. It was doubtless not (quite) for nothing that a pram, full of potatoes, rolled down the steps, absurdly echoing Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin and its mutiny against Tsarism. Film and its history (and, in this case, Soviet film's influence over capitalist Hollywood) became part of the postdramatic action, perhaps irrespective of meaning, certainly irrespective of the ability of either ‘side’ in the sometime battle of capitalism and socialism to feed its people. For the modern world has long been able to feed itself, provide for the needs of its inhabitants, many times over, and yet has not. Wotan proved conspicuous in his wastefulness in all three preceding dramas. What did he care if he ordered several times over at the (Al)exanderplatz restaurant, money being no object? Yet there were many for whom the denial of food, indeed that of other necessities and freedoms too, most certainly was an object. So long as the Gibichung regime provided for the people, Gunther and Hagen retained their loyalty. The frantic nature of provision as the crowd was worked up by Hagen (Figure 7) seemed suggestive both of the relationship (increasingly stretched) between supply and demand and of fascistic frenzy, all too familiar by the later 2010s. Redistribution would clearly require revolutionary transformation of some sort, even though the value of such attempts had long since been called into question on either side of the (now-fallen) Iron Curtain.

Figure 7. Götterdämmerung, dir. Frank Castorf, 2016 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

In that connection, it was difficult to see, when Siegfried, its leader, had disowned or remained merely oblivious to such a project, how this crowd might yet lay claim to revolutionary potential. Many of its individuals seemed more preoccupied with culinary and sexual excess; fake radicalism had always been a good path to sexual advantage. Petty flags of different ‘nations’ underpinned the violence as members of the crowd set upon each other and, perhaps most crucially, the poor Everyman who must serve them. Film both relayed the action and bade one take pornographic pleasure in watching the goings-on, as with ‘the news’ more generally. There was certainly no doubting the onstage, unmediatised brutality of the behaviour of these true followers of Siegfried and Hagen towards Seibert. Was he, however, ‘just’ an actor too? His ‘death’ at the beginning of the third act was knowingly, visibly stage-managed – film showing him smear himself in ketchup, presumably from his van, and leave himself for dead, awaiting the Rhinemaidens to bundle him into their car. They too then endured brutal attack by Siegfried.

And so, when the Immolation Scene came, when Brünnhilde threatened in Figure 8 to set Wall Street alight, nothing really happened. The contrast could hardly be starker with what Wagner, friend of the pyromaniacal Bakunin, had hoped would come to pass. Writing barely a year after fleeing Dresden for revolutionary exile, Wagner envisaged a cleansing fire spreading from European city to city, until it enveloped the world:

recall that day during the Dresden uprising when you met me on the Zwinger promenade and asked me in trepidation and with some concern whether I was not afraid that, at best, the result would be mob-rule? – … these people were still tied to the apron-strings of politics … were not yet the people they really are … it was this alone that subjugated them and made them appear to you as they did – men who were drunk on politics, and who blustered their way through the streets of the town – which they might have set fire to, with all the judicial splendour of our fair city of Dresden, had it only been granted them to act in accord with the fury they felt in their hearts. I have seen these people again in Paris and Lyons, and now know the future course of the world. – Until now we have encountered expressions of enslaved human nature only in crimes that disgust and appal us! – Whenever murderers and thieves now set fire to a house, the deed rightly strikes us as base and repugnant: but how shall it seem to us if the monster that is Paris is burned to the ground, if the conflagration spreads from town to town, and if we ourselves, in our wild enthusiasm, finally set fire to these uncleansable Augean stables for the sake of a breath of fresh air? – With complete level-headedness and with no sense of dizziness, I assure you that I no longer believe in any other revolution save that which begins with the burning down of Paris … Just wait and see how we recover from this fire-cure: if necessary I could finish painting this picture, I could even imagine how a man of enthusiasm might here and there summon together the living remnants of our former art and how he might say to them – who among you desires to help me perform a drama? Only those people will answer who genuinely share that desire, for there will no longer be money available, but those who respond will at once reveal to the world, in a rapidly erected wooden structure, what art is!Footnote 60

Figure 8. Götterdämmerung, dir. Frank Castorf, 2014 © Bayreuther Festspiele, Enrico Nawrath. (colour online)

Such was, of course, not to be, and the course the Ring project took would reflect Wagner's own conflict – as well as the post-1848 world's more generally – between resignation in the face of revolution's failure and hope that it might be reignited. The Immolation Scene itself and Wagner's various attempts, verbal and musical, at rewriting it, bear witness to that. With Castorf, however, all was shown to be worse than any revolutionaries remaining had feared. No more had the end of this miserable world come – and come whichever seemingly different historical path we might have taken – than a revolution had saved it and us. Various characters or figures onstage went through the revolutionary motions: a Rhinemaiden even dropped a Picasso out of the Wall Street window for safekeeping; or perhaps, on reflection, to generate a more brazen display of power to the plebs below. The Rhinemaidens survived; they even gave Hagen a kitschy funeral on the river, perhaps the Rhine. Video continued its quasi-orchestral task of commenting on, elucidating and frustrating the action; it had done so in the Funeral March too, Hagen marching back through a ‘Romantic’ landscape. Was there perhaps a hint of Edgar Reitz's Heimat 3 to all this: the need to tie things up after the fall of the Wall, yet no real ability to do so?

As Herbert Marcuse put it in his self-reflexive critique of Marxist aesthetics, The Aesthetic Dimension:

If art were to promise that at the end good would triumph over evil, such a promise would be refuted by the historical truth. In reality it is evil which triumphs, and there are only islands of good where one can find refuge for a brief time. Authentic works of art are aware of this; they reject the promise made too easily; they reject the unburdened happy end.Footnote 61

Rejection of the catharsis of unburdened tragedy, or gnawing away at it out of post- or non-revolutionary ennui, turned the dialectical screw once more. What a world is ours. The final, distinctly unsettling feeling, mixed with exhilaration at the conclusion of such an experience, was much as Boulez, at work on this work in this theatre, had said it should be: ‘Wagner refuses any conclusion as such, simply leaving us with the premises for a conclusion that remains shifting and indeterminate in meaning.’Footnote 62 Relative lack of stage drama – a drama of the underwhelming – offered the ultimate postdramatic sign-off and contrast to Wagner's score, if not to necessarily inadequate ‘traditional’ representations of the drama. Romantic and post-romantic idealism and their aspiration to totality – the Gesamtkunstwerk – were dealt, through a dialectic of the underwhelming, a Nietzschean hammer-blow: Wagner's Götterdämmerung subjected to the cunning and punning of Nietzsche's Götzen-Dämmerung, oder, Wie man mit dem Hammer philosophiert.Footnote 63 Indeed, the Ring and its attempt to create, as well as to destroy, an entire ‘world’ offered to postdramatic theatre more generally a brazen example of the idol of totalisation.Footnote 64 How, then, does one stage the end of a world? The question seemed as unanswerable in the Bayreuth Festspielhaus as on the streets outside; yet its answer seemed more necessary than ever.

IX

Where did that leave Wagner and Castorf? A host of critical voices, initially sceptical and in many cases downright hostile, declared their minds changed as they lived with the production over its five years. (The present writer counts himself amongst them.) Many have now spoken of it in the same breath as Chéreau, as a staging after which the work, its reception, its potentialities will not be the same again. It seems also to have proved a staging post for Castorf and his team, for whom opera, its necessary collaboration with musicians in the pit and on stage, and the challenge of operating with the constraints of the musical work concept – even when relaxed a little more than at Bayreuth – would seem to have afforded further challenge, even liberation. Gounod's Faust was staged in Stuttgart in 2017 as part of a larger Faust project, in which both parts of Goethe's epic were staged in one very long evening as Castorf's farewell to the Volksbühne, following a quarter of a century: almost exactly the same period of time Wagner worked on the Ring. That company's own future has been weighed in the neoliberal balance, the unlamented tenure of Chris Dercon, who abolished the ensemble in favour of using the theatre as a ‘space’ for visiting artists, terminated following artist occupation.

A 2018 From the House of the Dead for the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where Wagner has long been considered a ‘house god’, came as an intriguing pendant to the Ring: a thought-provoking alternative to Parsifal. A more fragmentary work emerged in some ways more conventionally, more in keeping with ‘itself’, than so emphatic a drama as the Ring. Many clues and connections, some perhaps red herrings, others undoubtedly playing with a Trotskyist alternative, presented further puzzles to piece together. La forza del destino at Berlin's Deutsche Oper incited near riots at its 2019 premiere, audience members rising to their feet to demand that Castorf be silenced and Verdi be granted his opportunity to speak. Walter Braunfels's Die Vögel also saw the rare light of day in late 2020, broadcast online from a well-nigh empty Munich theatre on account of coronavirus restrictions. At the time of writing, The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and Boris Godunov remained as future plans.

For the traffic of ‘influence’, or at least transformative encounter, has not been one-way. One might argue that it has necessarily travelled faster and fiercer from Wagner to Castorf, or indeed that it would be unduly reductive to speak of only two directions; the dimensions of the chess game are doubtless more than we can yet perceive. Wagner's orchestral writing and his formal methods created models of organisation and implications that did not previously exist, whether in the aesthetic or, should we consider such a thing to exist, the non-aesthetic realm. Many changes in the perception of reality have arisen in part through aesthetic transformation, which is certainly not to be divorced from technological developments. Likewise, confrontation with a Wagner score, if undertaken in a remotely seriously fashion, would seem to have changed Castorf in Bayreuth just as much as it had changed Boulez and Chéreau.

Heiner Müller, a crucial influence on Castorf, offered a celebrated observation that ‘the essential thing about theatre’ was ‘transformation. Dying. And fear of that final transformation is general; one may rely on it; one may depend on it.’Footnote 65 Müller must have been especially fascinated by that element of Isolde's mysterious Verklärung or transfiguration when directing his ‘anti-illusionist’ Tristan und Isolde at Bayreuth (1993–9).Footnote 66 For Wagner too, in a passage moving from generalities to specific reference to the fourth scene of Das Rheingold, told his fellow composer and revolutionary August Röckel: ‘We must learn to die, and to die in the fullest sense of the word; fear of the end is the source of all lovelessness, and this fear is generated only when love itself is already beginning to wane.’Footnote 67 The world had neither died nor been transformed in Castorf's Ring. And yet, drama, be it Brechtian, Wagnerian, even Aristotelian, had emerged stronger: not despite postdramatic treatment, but rather on its account.

‘From the beginning’, we read in Lehmann, when he returned some years later to the theme of postdramatic theatre, yet this time in explicit relation to politics, ‘the articulation of the tragic was closely connected to basic questions of the political, the polis, to history, power and conflict. Today is no exception to this rule. There can be no private tragedy. Where we find the tragic, we hit upon the political.’Footnote 68 That surely includes tragic avoidance of ‘necessary’ tragic outcome, of catharsis. In that history of modern revolution in which Wagner's life and work continue to play out, such had been the case all along.

Writing for Bayreuth, in which revolution and counter-revolution were entwined from the outset, Boulez extolled in a 1977 programme essay the virtues of the ‘amazing’ Götterdämmerung scene in which Alberich visits Hagen (‘Schläfst du Hagen, mein Sohn?’). It moved him, he wrote, ‘for reasons that are probably not directly related to the drama’, but which we may read as related to its reception history, both before and after Chéreau (and Castorf). Wagner, Boulez wrote, ‘seems here to be conducting a kind of dialogue with his own double’. (Was this perhaps a seed of Boulez's 1985 Dialogue de l'ombre double?) Its ultimate subject, Boulez thought, was:

a questioning of the future, an uneasiness about generations to come. Will my concerns and my achievement be understood in years to come? Shall I survive in those who follow me? The whole scene reveals a deep uncertainty about communication, and the sense of doubt in the final ‘Sei treu!’ is heartrending. … I cannot help but think that this anguished questioning, which is essentially about the ring, refers in fact to the whole work and its future validity.Footnote 69

It is not enough to say that the best way to remain truly faithful is to be unfaithful. To be werkuntreu is no better measure of ‘future validity’ than to be werktreu. Infidelity covers a multitude of sins; sometimes a sin is just a sin. We can be sure, however, that, for Wagner's work to have retained such validity another two centuries after his birth, it will have needed to continue its questioning of our concerns, aesthetic and political, as well as to have been questioned by them.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank the following for reading and commenting on earlier versions of this article: the editors and anonymous readers of the Cambridge Opera Journal, Björn Heile, Phillip Koyoumjian, Barry Millington and Hugo Shirley.