‘To my mind what supports the carer is not encouragement in the conventional sense. Instead, it is to be part of a learning system greater than himself. Anxiety from puzzlement, and often a degree of feeling overwhelmed by human problems, are best alleviated when we understand what is going on.’

The appointment to a consultant post should be a cause for celebration. It marks the end of a protracted period of training, the opportunity to practice independently, the potential to develop and shape one’s own service and, of course, the financial rewards that consultant status brings. Yet it is clear that, for many, the transition from specialist registrar (SpR) to consultant is far from easy. Why is this?

By the end of postgraduate training, a psychiatrist will have accrued a great deal of knowledge and be technically highly skilled in dealing with mental illness. However, our experience is that many feel far less well prepared for the emotional and interpersonal challenges that this new professional role brings. Management courses and ‘shadowing the manager’ have their place. But perhaps nothing can prepare the fledgling consultant for the many, and often ill-defined, tasks that others will expect them to fulfil from their first day, when it feels as though the buck really does stop with them. It is not surprising that many suffer what might be described as a crisis of professional identity, questioning what is, and is not, their job.

To compound the problem, the way that new consultants feel about themselves ‘in role’ may be quite at odds with how others, including managers and other team members, define their roles and responsibilities. It is little wonder that many report this transitional period as one of the most stressful in their professional lives (Reference DeanDean, 2003).

All periods of significant transition throughout life are accompanied by a period of unease, enhanced vulnerability and a degree of identity confusion. The transition from SpR to consultant grade is, in this sense, no different.

Mentoring

The increased emphasis being placed on mentoring schemes by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and others (Reference GrantGrant, 2002; Reference Roberts, Moore and ColesRoberts et al, 2002; Reference DeanDean, 2003) is evidence of a growing recognition of the need to support young consultants through this period and help them to develop a robust professional identity.

Traditionally, mentoring schemes are run on an individual basis, with an older, and hopefully wiser, senior consultant providing support and advice for a younger colleague. A number of schemes have been set up around the country, and clearly mentoring has been an invaluable experience for many.

We have taken a slightly different approach in the West of Scotland, setting up what we have called the transition group.

The transition group

The transition group is a peer support group for psychiatric SpRs and newly appointed consultants working in the West of Scotland. It meets for one evening a month at the Scottish Institute of Human Relations in Glasgow. There are 12 participants and 2 facilitators.

The purpose of the group is to give participants an opportunity to think about some of the tasks and constraints involved in taking on the role of a consultant psychiatrist. A further aim is to help individuals understand the dynamics of their work situation and to enhance their leadership skills.

The main method of study is experiential. Participants have the opportunity to present ‘live’ work issues in a group setting and to think about some of the organisational pressures that affect their role as consultants.

Since all the participants work in the same region of the country, confidentiality is of paramount importance and this is something that is openly discussed in the group. Confidentiality is seen as a shared responsibility.

Further information about the group is shown in Box 1.

Box 1 The West of Scotland transitional group: some questions and answers

| How are group members selected? | There is no formal selection process. The Chairman of the Postgraduate Committee in the West of Scotland informs SpRs who are nearing the end of their training about the group. They are then expected to approach one of the facilitators (G.W.) if interested. New consultants hear about the group by word of mouth. |

| Is it a closed group or do members graduate from it, with new members enrolled to replace them? | Group members are expected to attend for a minimum of 1 year. Some leave at the end of the year, but others decide to stay on. This means that there is a new intake in January each year. Commonly, people join the group as SpRs but stay on as consultants. This means that their experience does truly span the transition. |

| Are there any potential conflicts if two or three members of the same service are in the group? | This might potentially be a problem, but so far it has not been. Issues of confidentiality are discussed and, if this matter were not talked about openly, the facilitators would raise it. |

| Are there differences in the issues at stake for specialist registrars as opposed to newly appointed consultants? | Yes. Our experience is that SpRs tend mainly to listen and contribute, rather than bringing their own organisational issues. However, we think this prepares them well to be able to use the group when they take on full consultant status. |

| What is the theoretical framework underpinning the work of the group? | Is it possible to envisage that a support group without overt dynamic interpretations would be equally helpful? Both of the facilitators are psychoanalytic psychotherapists and they use psychoanalytical and systems thinking to inform their contribution. However, the purpose of the group is not to provide therapy and it therefore has a much more informal atmosphere. |

Change and transition

Constant change is a fact of contemporary organisational life. At work, change is ‘in the air that we breathe’ (Reference Amado and AmbroseAmado & Ambrose, 2001), and the idea of a team or organisation in static equilibrium with the environment in which it exists is untenable.

This applies particularly to the situation faced by those who work in the modern mental health service. The impact of community care, with a flattening of authority structures and increased fluidity of role definitions, the increased emphasis on consumer involvement and the apparent move away from a management ethos based on ‘command and control’, means that latter-day consultants find themselves in an organisation which is in a state of perpetual flux.

Individuals naturally resist change. Reference Obholzer, Obholzer and Zagier RobertsObholzer (1994) has argued convincingly that in contemporary society the diminution in the importance of social institutions such as family and religion means that, for many, a sense of personal identity is fundamentally tied up with their identity at work. Under these circumstances, any significant change raises primitive anxieties relating to loss of identity and self-worth and a sense of not belonging to a group with shared values. Not knowing who or where we are in the scheme of things can lead to feelings of acute isolation and puts us in touch with the ‘nameless dread’ described by Reference BionBion (1962).

In this situation, social systems, and the individuals that make up these systems, may regress to more primitive ways of ‘thinking the organisation’. We can all fall prey to the use of primitive defence mechanisms such as denial, splitting and projective identification to avoid the anxiety that change brings (Box 2) (Reference MenziesMenzies, 1964).

Box 2 Definition of terms

In the following definitions, ‘people’ may be individuals, a group or a whole organisation

- Denial

-

A state of mind in which people live out a fiction because the truth is too painful to deal with at the time

- Splitting and projective identification

-

The psychological mechanism that people use to ‘get rid of’ unwanted aspects of their character by finding these features in others, who can then be despised and attacked

- Containment

-

The process by which people temporarily accept what is projected into them. The ‘container’ processes the rawness and primitiveness of what is projected to the point where the ‘projector’ can take it back and own (re-introject) it as their own

Change is often felt to be an unwelcome intrusion from the external world (government, managers, the College, consumers), but in this article we are particularly interested in an internal process that leads to a necessary development and maturation of the self.

We use the term transition (after Reference Bridger, Cooper and PayneBridger, 1978) here to describe a particular form of change that requires the new consultant’s identity or way-of-being in the world to change in a fundamental way.

All of life’s transitions are painful. Think of the adolescent trying to fashion an identity, the baby being weaned from the breast, the woman struggling to become a mother or the loss felt by the bereaved. All involve a degree of emotional turbulence and confusion, with a longing for the old identity alongside a developmental push towards a new one.

When we are thinking about transition we are describing a process with no clear end point. Nobody really knows how it will turn out, but we do know that all transitions involve a fundamental reexamination of who and what we are, even if this processing is occurring at a largely unconscious level.

Taking up the role of a consultant involves many challenges, but in addition to the real and very practical organisational tasks to be faced there is also the anxiety inherent in trying to establish and feel at ease with one’s new professional identity. In transition the consultant needs time and space to ‘fill out’ and personalise the role he or she has been assigned. The role may be ‘given’ by the organisation, but each consultant has to make it his or her own before it can be felt, and seen to be, truly authentic.

In the next section we take up the issue of a consultant’s growing professional identity and the factors that influence it. In particular, we focus on one aspect: the growth of personal authority, which seems to us to underpin many of the issues facing our group of consultants.

Issues of identity

What do we mean when we talk of a self? Sutherland offers the following definition :

‘The self is fashioned from early experience into an identity – the unique grouping that each individual has of character, abilities, and social relationships into a cohesive organisation that preserves a sense of continuity throughout the life cycle. This identity or self is a dynamic structure in constant interaction with the social environment and its culture. When the latter no longer provides the affirmations the self requires, then the self tends to disintegrate, with widespread disturbances in the sense of well being and hence various pathological reactions’ (Reference Sutherland and ScharffSutherland, 1994: p. 212).

So when we talk of our self we are describing the way we view what we are and how we are with others in the world. For most of us, and for most of us most of the time, the self is felt to be a relatively constant mental structure. However, we are aware that for all of us the self is not quite the same from place to place and from time to time. The self is a dynamic structure, influenced by the setting in which it finds itself, and it also changes and matures or regresses over time.

For example, for most of us, there is a reasonable continuity between how we are at home and how we are at work. We feel ourselves to be the same person, but not exactly the same person, and when we cross the home/work threshold we are aware of being defined and defining ourselves in a subtly different way.

For all the consultants in our group a central issue seemed to relate to their professional self – what did it mean to be the consultant in this team in this organisation at this particular time?

Certain aspects of the role seem relatively clear-cut. For example, the consultant as the member of the team who carries medical responsibility, the consultant as an expert in diagnosis and medical treatment, and the consultant as the one who carries authority to implement the Mental Health Act.

Other areas seem far less clear. Are they leaders of teams or simply highly specialised technicians? Are they managers, and if so what does this mean? Do they have any responsibility for ensuring the well-being and effective functioning of other team members? Is it their job to be ‘consulted’ or to act as frontline clinicians? (This, incidentally, is part of a wider debate in the psychiatric literature: see for example Reference Kennedy and GriffithsKennedy & Griffiths, 2001).

Repeatedly, it seemed to us that the conflicts which people brought to the transition group stemmed from a more fundamental question of what and who they were when they were at work.

The ‘self-in-role’

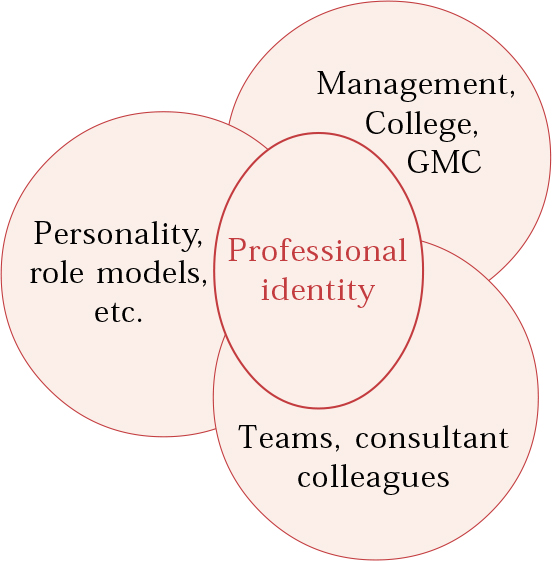

We use the term ‘self-in-role’ to emphasise that each consultant is uniquely different (as well as being the same) and that their professional self is a function of multiple factors: their personality, their identification with role models, the role they are assigned by their organisation (both explicitly and implicitly) and how they are allowed to be by those in their immediate working environment (Fig. 1). We think of the new consultant as being on a developmental and motivational path, the end point of which is to achieve a professional identity.

Fig. 1 Professional identity: self-in-role.

Because of the link between the personal and the person-in-role, these transitions can stir up unresolved issues from earlier phases of development and create difficulty for those in such a transition.

To illustrate what we mean, consider the issues of authority and leadership for the ingénue consultant. Each will react differently. Some, for example, will display a quiet authority. Others will deny the need for authority or take on a deeply entrenched authoritarian stance.

We would argue that this reaction depends to a large degree on each individual’s experience of being on the receiving end of authority. We all internalise what we experience when we are growing up. Some may have had relatively ‘good’ authority figures on whom to consciously or unconsciously base their attempts to exercise authority. Others may have been dominated or even bullied and struggle with their own authority, becoming overly reserved or bullying in a leadership role.

Like it or not, consultants are usually expected to take on a leadership role in one form or another. So it is perhaps unsurprising that this issue was a core concern for members of our group. It is to this issue that we now turn.

Authority and leadership

The multidisciplinary psychiatric team has a primary task: to provide a psychiatric service to a given population. To do so, it requires an organisation, along with its many features, including a decision-making process.

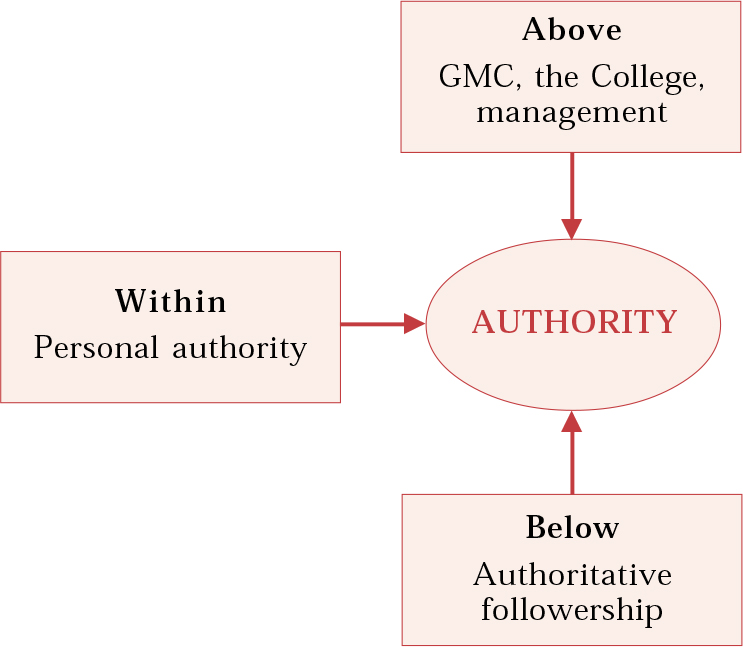

Obholzer defines authority as the right to make a decision that is binding on others. If an individual is designated as an organisation’s manager and leader, it is important to be clear how that individual derives his or her authority. A consultant’s authority can be thought of as deriving from three areas (Fig. 2): first, from above, for example from the trust and through the chief executive; second, from below, sanctioned by those who are subject to this authority (the ‘authoritative followership’); and third, from within him- or herself. The individual’s ability to ‘fill out’ the role of manager/leader will depend on a complex blend of personal factors linked to the whole development of that individual. Exercising authority well can be thought of as dependent on a good mix from all three sources.

Fig. 2 The determinants of organisational authority.

A full blend is likely to be unachievable. In practice, the best the manager/leader can aspire to is a ‘good enough’ situation (Reference WinnicottWinnicott, 1965). Plenty of personal authority and solid support from the managed can be hampered by those above if they will not sanction the decision-making process. Any amount of senior backing and personal authority will be ineffective if it is not accepted by the managed. At best, this will produce an authoritarian dynamic, with its attendant strengths and weaknesses.

Obholzer makes a distinction between management and leadership, with the former being more focused on the present and concerned with the smooth functioning of the organisation, and the latter being more focused on the future and concerned with a conception of how things are to develop (what we might call ‘the vision thing’).

In the National Health Service (NHS) it is necessary to make a distinction between clinical authority and management (organisational) authority. Consultant psychiatrists derive their clinical authority from training, qualifications and their professional role, linked as it is to the various self-managing professional bodies (for example, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the General Medical Council and the British Medical Association). Arguably, for the new consultant the ability to exercise both of these types of authority is an important developmental task. In our experience, new consultants are often poorly prepared to deal with the complex organisational issues involved in taking on managerial responsibility. This is partly to do with prior training and partly because learning in this area needs to be based on experience.

In the contemporary situation in psychiatric hospitals/services, consultants need to be able to ‘think organisationally’, to understand their role and the nature of the authority and responsibility it carries. We think that this has become a much more complex task in the present-day NHS, characterised as it is by the multidisciplinary team within a larger organisation that seems to be caught up in constant change.

Doctors, nurses, psychologists and others are accountable and allied to their own professions within the NHS organisation as well as to each other in the team. Trusts have appointed managers (rarely doctors) to teams, whose precise management task and authority is unclear. Nurses, psychologists and others have up-graded their training and qualification level and seek to attain increased status and authority within their settings.

A variety of ways of organising and managing psychiatric services now exist, and yet the idea of the consultant as manager/leader persists.

As the relationship between the different professions becomes less hierarchical and less assumed, new consultants are entering into organisational life with the complex task of determining their position in the management/leadership system. This will involve the development of a professional identity in both clinical and organisational terms. ‘I’ll just concentrate on my patients’ as a solution to these challenges is as understandable as it is unrealistic.

The patients are shared. Filtering, assessment and treatment/care systems need to be organised at the team level. Perhaps most importantly, the capacity to deliver effective treatment and care may be thought of as depending on the cohesiveness and morale of the team as an organised whole.

Becoming increasingly aware of and comfortable with their professional identity and role in the organisation is a crucial task for new consultants. This is a process that requires supported personal and professional development if it is to succeed. Our experience suggests that a transitional group can play an important part in the new consultant’s work life.

An example: The away-day

The problem

A newly appointed consultant (Dr A) had indicated before the start of a transition group meeting that he would like ‘a bit of time’ to discuss an issue. He focused on one of the facilitators and said that he was looking for some advice. A sense of urgency was conveyed, but also the fact that it wouldn’t take up much time.

The problem presented was ostensibly to do with an away-day that was being proposed for the community team in which he worked on a part-time basis. We had heard about this team in a previous group meeting and knew that Dr A was trying to work out his role and authority within it. We also knew that the team was struggling to move from a traditional model of community psychiatric nurse (CPN) duties to working more directly with primary care.

Dr A had become increasingly frustrated at the team’s inability to adapt to changes which were largely imposed by a reorganisation of the structure and function of community teams across the trust. His complaints focused particularly on two senior members of nursing staff, whom he thought intransigent and opposed to any change. It was clear that, as the team’s consultant, he felt ‘abused’, in that he simply had to deal with crises as they arose, but was not given the opportunity to participate in decisions about the way the team functioned. He seemed increasingly isolated and frustrated in his work.

The immediate problem was that, at the suggestion of one of the charge nurses, he had agreed (with a vague feeling of unease) to meet with an external facilitator, funded by drug company sponsorship, to set up an agenda for the away-day.

His sense of foreboding was heightened when the subject of the away-day came up in a team meeting and there seemed to be only a vague memory that any such event had ever been agreed.

As Dr A talked in the transition group, it became clear that this recent issue was simply the tip of the iceberg and that powerfully destructive emotions were involved. Dr A seemed to be carrying all the anxiety and worry about the need for change, while the team, perhaps in a state of denial, seemed to be ‘turning a blind eye’ (Reference SteinerSteiner, 1985) to the problem. This is a clear example of splitting and projective identification at work in an organisation (Box 1).

The process

The group, as is often the case, initially simply listened, asked for clarification and, at times, shared their experience of similar situations. They mulled over with Dr A what he might say when he met with the outside facilitator. What had he thought of?

Dr A said that the issue of leadership should definitely be high on the agenda, but the group pointed out that this might be seen as provocative. When he was asked to imagine what he would like to come out of the away-day he replied forcefully that the only solution was for certain members of staff to leave.

The group suggested that this was unlikely to happen and, in any event, it did not seem to tackle the underlying anxieties alive in the team. One member of the group described another situation, where it had been helpful to review the very simple question of what the primary task of the team was. This seemed particularly relevant, given the changing role and patient group that Dr A’s team was being expected to accommodate.

All of these suggestions seemed helpful, but somehow did not seem to get to the nub of the problem. As is often the case, it is only when the particular consultant’s role and what they were being expected to carry was questioned, that real movement seemed possible.

The group pointed out to Dr A that he seemed to be carrying all the anxiety for the team and, although he was given the authority, or perhaps pseudo-authority, to represent the team’s views to the external facilitator, he did not actually feel that he could do that. Perhaps he was being set up to fail?

This led, seemingly appropriately, to a general comment by one of the facilitators about projective identification (Box 1) and the way that individuals can be unconsciously manipulated into ‘carrying’ certain unacceptable feelings for a group (in this case, the hopelessness and anger about working as a team and the need to change). It was also suggested that, because of Dr A’s part-time commitment to the team, he was ideally placed to be its scapegoat.

In Dr A’s account there seemed to be an urgency to take action prematurely, without prior thought, and this is a common problem in busy community teams. This was conveyed powerfully to the group in the way that the problem was presented by Dr A in a request for a quick bit of advice (an example of mirroring: see below). Action can be a way of avoiding feeling and thought, and there was a growing realisation in the group that Dr A did not automatically have to take the action that was being suggested. Perhaps it was far too early for this team to be thinking about an away-day to discuss their differences and their supposed common goal? Maybe a lot of ground work was needed before an away-day could even be considered? It was pointed out that teams often idealise what can be achieved when staff sit together to talk about their working relationships, and Dr A seemed to confirm this when he spoke about his fear of the away-day and how things might be said that would be regretted later. The group also questioned whether or not it was really Dr A’s responsibility to organise the away-day.

The proposal

The group formulated the following plan of action:

-

1 Dr A should go back to the team and tell its members that he did not feel he had the authority to represent them all.

-

2 He would propose that as many of the team as possible should hold a preliminary meeting with the external facilitator to think about what, if any, further work could be done within the team on their working relationships.

-

3 He would suggest that the team consider a more prolonged period for this work, with monthly meetings and an external facilitator. The transition group felt it important that the whole team should select and agree on the facilitator and that the trust, rather than a drug company, should sponsor the facilitation, emphasising that this was important business for the whole organisation.

Outcome

Dr A seemed relieved, in no small part, we felt, because something of the emotional content of what had been happening to him at work had emerged in the group and had been worked through. His position had been accepted, but also gently challenged.

It seemed as though something had been freed within him, enabling him to question the role he had been assigned by his work colleagues. We felt that he now had a more realistic view of his own authority and that he was going back to the real world of his work situation with the authority of the transition group behind him: an example, we think, of containment (Box 2).

We were aware that the group had not addressed the issue of Dr A’s own personality and how this impinged on the problem at work. We were also aware that we were hearing only one side of the issue and that we did not know what the other team players in this organisational drama were feeling. Nevertheless, it felt that there had been some movement and Dr A agreed to bring this problem back to a subsequent meeting.

The facilitating environment

The question of how we support individuals who are struggling to find their feet is a crucial one for any organisation. As we have suggested, an individual’s capacity to deal with change varies and is dependent on their personality and previous life experience. For example, a basic sense of trust in the world (Reference EriksonErikson, 1980) is essential if a person is to feel contained enough to trust in the process of change without resorting to pathological avoidance. Personal development takes time, cannot be forced and inevitably results in a certain amount of friction and disillusionment for all concerned. This needs to be understood and allowed.

Crucially, however, the ability to grow and develop in a job is heavily dependent on the way our organisation and the teams in which we work support us in this task. This level of benign support cannot be assumed and it is clear that new consultants are often faced with crippling undermining of their role and may be on the receiving end of powerful negative projections. We all know that working in teams can make you ill. On the other hand, healthy organisations recognise that they have a crucial role to play in helping their staff to develop, and this includes containment of the anxieties thrown up by change.

Reference Bridger, Cooper and PayneHarold Bridger (1978) used Winnicott’s ideas about transitional space to develop a theory regarding the management of organisational change. He wrote of the ‘double task’ facing managers: the first is to ensure that the work is being done, but the second, crucial for the health of the organisation, is the ‘periodic suspension of business’ in order to understand how the first task is being undertaken.

We see our role as facilitators of the transition group as helping in the development of a space for reflection (Reference HinshelwoodHinshelwood, 2001), a reasonably supportive environment where participants can learn to think about themselves in role.

Over time, the individuals form a group in which growing mutual trust and commitment increases the risks the participants are prepared to take as they disclose their uncertainty, confusion and anxiety about what confronts them and how they are coping with it.

The facilitators begin to be accepted and authorised to comment, not only on instrumental themes – perhaps leading to practical action – but also on the dynamics of how the professionals are relating in the cases discussed, and how the individual consultant is functioning at an emotional level. The group members may be a little tentative about this way of working at first (and will, of course, vary in their capacity and willingness to participate) but over time, as the group grows, its members find real value in understanding the underlying dynamics of their situation.

Mirroring

Group facilitators must be alert to any mirroring (Reference MattinsonMattinson, 1975) of the problem in the way the issues are raised and dealt with in the group. When a transition group is working well the problem ‘goes live’, the group members acting as if they are directly involved in it. Much can be learned about the problem, not simply from what is presented but how it is presented and how the group responds and manages it. This way of thinking taps into deeper layers and can provide clues as to what is going on at both a conscious and an unconscious level. In time, the group may begin to attend to such factors in others and in themselves.

As noted in the away-day example, the mirroring process was clearly demonstrated when Dr A addressed himself (pointedly) to one facilitator and sought to pressurise him to take on the problem. This mirrored or acted out what his colleagues had done to him. An analytical perspective would see this as relevant process information that leads to a fuller understanding of his situation at work.

The role of the transition group

The relationship, cognitive and problem-solving skills learned within a transition group can deepen how new consultants think of themselves in their interactions within the work group. The application of this thinking (and its methods) in the workplace can enhance the reflectivity of the work group itself, helping to create what Reference SchönSchön (1983) called reflective practitioners. Ideally, we would argue, the group is internalised by its participants (as is a good teacher, coach or parent) and becomes a source of inner support. Thus, ‘the group in the mind’ can have a continuous presence beyond the monthly meetings.

We believe we have created a context within which new consultant psychiatrists (and final-year SpRs) can explore their experience of making the transition to becoming practitioners who possess a robust professional identity. To do this, they must invest something of themselves in the group and be prepared both to help and to be helped. The facilitators sit at the edge of the group, neither truly part of it, nor truly apart from it. From this perspective they have a view which, if communicated adequately, may direct the members towards self-discovery and realisation. This can be achieved only by the collective building of a safe, reflective space within which to learn – intellectually and emotionally – from the experiences of the workplace.

MCQs

-

1 During periods of rapid organisational change:

-

a individuals at work may regress to more primitive states of mind

-

b feelings of excitement, optimism and corporate solidarity are common

-

c individuals fear a loss of identity and self-worth

-

d managers should take up the depressive position

-

e individuals may rapidly become deskilled.

-

-

2 The transition from specialist registrar to consultant psychiatrist:

-

a is usually relatively straightforward

-

b is often associated with a period of identity confusion

-

c is easier in an organisation with a less hierarchical organisational structure

-

d has a clear end point

-

e can be helped by peer group support.

-

-

3 A strong sense of personal authority in the work setting:

-

a is dependent on support from the management system in an organisation

-

b requires the support of ‘the managed’

-

c takes the average clinician up to 2 years to develop

-

d is in part based on early experiences and personality development

-

e is best supported by a ‘command and control’ management style.

-

-

4 The following are associated:

-

a Bion and nameless dread

-

b Bridger and the double task of management

-

c Mattinson and reflective space

-

d Erikson and authoritative followership

-

e Hinshelwood and reflective space.

-

-

5 Mirroring:

-

a is a term used to describe the reflective capacity of group members

-

b has a negative impact on the containing function of a group

-

c is a source of important information about organisational problems

-

d is generally destructive when present

-

e was first described by Schön.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.