1 Introduction

Mental health care provision has moved from a hospital-based model to community-based services across most European countries Reference Shen and Snowden[1]. However, hospital treatment still plays an important role in the management of large numbers of patients with mental disorders and constitutes a major determinant of costs in mental health care Reference Stensland, Watson and Grazier[2].

The aim of cost reduction is one of the reasons why mental health policies recommend shortening length of stay (LoS) in psychiatric inpatient services. These recommendations are supported by the lack of significant differences in re-hospitalisation rates and other clinical outcomes between short and long-term hospitalisations Reference Babalola, Gormez, Alwan, Johnstone and Sampson[3]. Also, patients commonly report the experience of long hospitalisations as unpleasant and stigmatising Reference Johnstone and Zolese[4].

Understanding which patients stay longer in hospitals may help to reduce LoS, as services can target specific patient groups adjusting their in-patient treatments or providing alternative options. Various studies have explored which patient-level characteristics are associated with longer LoS [Reference Bessaha, Shumway, Smith, Bright and Unick5, Reference Newman, Harris, Evans and Beck6]. The results of these studies have been inconsistent. It is unclear whether the different results of studies reflect true differences in the predictive value of patient characteristics across different regions and countries, or whether they are due to methodological inconsistencies in data collection and analyses across studies.

For example, some studies have identified psychotic disorders as associated with a longer LoS [Reference Bessaha, Shumway, Smith, Bright and Unick5, Reference Douzenis, Seretis, Nika, Nikolaidou, Papadopoulou and Rizos7, Reference Frieri, Montemagni, Rocca, Rocca and Villari8] compared to other mental disorders, whilst others have found that people with affective disorders have longer LoS than people with other diagnoses Reference Wolff, Mccrone, Patel, Kaier and Normann[9].

More severe clinical conditions are usually associated with longer LoS [Reference Bessaha, Shumway, Smith, Bright and Unick5, Reference Page, Cunningham and Hooke10–Reference Pauselli, Verdolini, Bernardini, Compton and Quartesan12]. However, different studies have considered different indicators of severity, such as symptom levels (measured on different instruments) [Reference Smith, De Nadai, Storch, Langland-Orban, Pracht and Petrila11, Reference Pauselli, Verdolini, Bernardini, Compton and Quartesan12], type of admission (voluntary or involuntary) Reference Shinjo, Tachimori, Sakurai, Ohnuma, Fujimori and Fushimi[13], and risk to self and others [Reference Miller, Hitschfeld, Lineberry and Palmer14, Reference Ries, Yuodelis-Flores, Roy-Byrne, Nilssen and Russo15].

Similarly to clinical severity, poor social functioning [Reference He, Ning, Rosenheck, Sun, Zhang and Zhou16–Reference Hopko, Lachar, Bailley and Varner27] is a widely accepted predictor of longer LoS, although it is inconsistently measured across studies. A number of indicators were found to be associated with longer LoS, such as lack of family support [Reference He, Ning, Rosenheck, Sun, Zhang and Zhou16–Reference Blais, Matthews, Lipkis-Orlando, Gulliver, Herman and Goodman19], social isolation [Reference Barnow, Linden and Schaub20, Reference Wu, Ouyang, Yang, Li, Wang and Yi21], homelessness [Reference Russolillo, Moniruzzaman, Parpouchi, Currie and Somers22–Reference Tulloch, Khondoker, Fearon and David24], and unemployment [Reference Masters, Baldessarini, Öngür and Centorrino25–Reference Compton and Craw27].

A central problem of the current evidence is that all of the studies in the field have been conducted within one individual country (most often in the United States), with inconsistent findings reported in different countries.

To address the question as to whether different results of studies on predictors of LoS reflect true differences or methodological inconsistencies, we conducted a study across five countries (i.e. Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, United Kingdom [UK]), assessing more than 1000 patients in each country with a consistent methodology. The large sample size allowed for the statistical testing of interaction effects of predictor variables with countries, i.e. whether the predictive value of a given predictor variable was similar or significantly different across countries.

Specifically, we addressed the following research questions: a) which patient characteristics are associated with longer LoS in a large sample of in-patients across different European countries? b) is the predictive value of the identified predictor variables consistent or different across countries?

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

This is a prospective study, carried out in hospitals in five European countries. It is part of the COFI project (COmparing policy framework, structure, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Functional and Integrated systems of mental health care), funded by the European Commission Framework Programme 7 Reference Giacco, Bird, Mccrone, Lorant, Nicaise and Pfennig[28]. COFI was conducted in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland and the UK. These countries differ in the number of psychiatric beds per population, and in funding systems, type of provider organisations, and governance arrangements for mental health services. Hence, the study explored predictors of LoS across national contexts with differences in several characteristics that may influence LoS in in-patient treatment.

The sample size calculation was estimated in order to enable us to capture a 5% difference in re-hospitalisation rates within one year from an index hospital admission according to the primary research question of the COFI study Reference Giacco, Bird, Mccrone, Lorant, Nicaise and Pfennig[28]. We calculated a target sample size of 6000 patients overall, with on average 1200 patients per country Reference Giacco, Bird, Mccrone, Lorant, Nicaise and Pfennig[28]

Based on different expected numbers of hospital admissions per country within the recruitment period, we included a different number of hospitals in each country. Hospitals were purposively selected considering the characteristics of the area (rural or urban and high or low population density) and the organisation of care across hospital and community services (with or without personal continuity) Reference Giacco, Bird, Mccrone, Lorant, Nicaise and Pfennig[28].

The inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age or older; International Classification of Disease-10 Reference World Health Organization[29] diagnosis of psychotic disorder (F20–29), affective disorder (F30–39) or anxiety/somatisation disorder (F40–49); being hospitalised in a general adult psychiatric inpatient unit; sufficient command of the language of the host country to provide written informed consent and understand the questions in the research interviews; mental capacity to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of organic brain disorders and/or severe cognitive impairment affecting the ability to provide information on the study instruments.

2.2 Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained in all five participating countries. Belgium: Comité d'Ethique hospitalo-facultaire des Cliniques St-Luc; Germany: Ethical Board, Technische Universität Dresden; Italy: Comitati Etici per la sperimentazione clinica (CESC) delle provincie di Verona, Rovigo, Vicenza, Treviso, Padova; Poland: Komisja Bioetyczna przy Instytucie Psychiatrii i Neurologii w Warszawie; and UK: National Research Ethics Committee North East—Newcastle & North Tyneside (ref: 14/NE/1017).

2.3 Procedures

Every patient admitted in psychiatric wards of 57 hospitals (10 in Belgium, 4 in Germany, 14 in Italy, 6 in Poland, 23 in UK) was screened between 1 st October 2014 and 31 st December 2015. All eligible patients were approached by study researchers for the first assessment within two days from the hospital admission. One of the researchers discussed the study with the patients in detail and obtained written informed consent.

Data on socio-demographic characteristics, social situation, and formal status of admission were obtained through initial face-to-face interviews. Other information was collected by clinical records: psychiatric and non-psychiatric diagnoses (according to ICD-10) at admission and at discharge, severity of illness (evaluated by Clinical Global Impression Scale, CGI) Reference Guy[30] and LoS.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Outcome variable

The outcome variable was LoS, which was defined as number of nights spent in the psychiatric wards of a hospital. For several reasons, the number of included hospitals per country varied. Whilst this resulted in differing sample sizes per hospital, we had a substantial number of patients (i.e. >1000) in each country and therefore decided to analyse on country level.

2.4.2 Predictors

We selected putative predictor variables based on the existing literature [Reference Bessaha, Shumway, Smith, Bright and Unick5–Reference Hopko, Lachar, Bailley and Varner27]: age, gender, marital status, migrant status, education, homelessness, living alone, unemployment, receiving benefits, diagnosis of psychotic disorder, comorbid diagnosis of substance misuse, severity of symptoms (Clinical Global Impression score–CGI), first admission versus repeat admission, and legal status, i.e. voluntary versus involuntary admission. Social isolation was assessed by asking patients whether they had met a friend in the previous week and whether they had anyone they would call a close friend.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, i.e. mean, standard deviation and median were calculated for LoS. For the other socio-demographic variables, mean and standard deviation or frequencies were used as appropriate. Missing data for LoS were 0.2% (20 out of 7302 cases). We imputed missing cases using average values per country.

Associations between individual patient-level variables and LoS were tested using mixed effects linear regression models with a random intercept for hospital.

We used parametric tests, despite the dependent variable (length of stay) being non-normally distributed. For studies with a large sample size, the robustness of parametric tests to deviation from normality is high and they are a more conservative option to detect differences Reference Fagerland[31].

Each variable with a univariable association with LoS that was significant at p ≤.10 level was then simultaneously entered into a mixed effect multivariable regression model. The multivariable model was adjusted for country effects as a fixed factor. To test the goodness of fit of the multivariable model, we conducted a likelihood ratio test comparing the fitted model to the null model. Following this, we estimated mean and standard deviation for LoS in each country, adjusted for significant predictors in the multivariable model.

In a second step, we fitted an interaction term between any variable showing a significant association in the multivariable model (p <.05) with LoS and country, adjusted for all other significant predictors, including a random intercept for hospital. We estimated descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of LoS from this model for each dichotomous variable, overall and by country.

We calculated descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of LoS for each country for any dichotomous variable which was associated with LoS of stay in the multivariable model, adjusted for significant predictors within the model and country effects.

We also then performed pairwise comparisons between countries, adopting a more strict criterion for significance (p <.01) in order to reduce the effect of multiple testing.

The statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.0 Reference STATACORP[32].

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

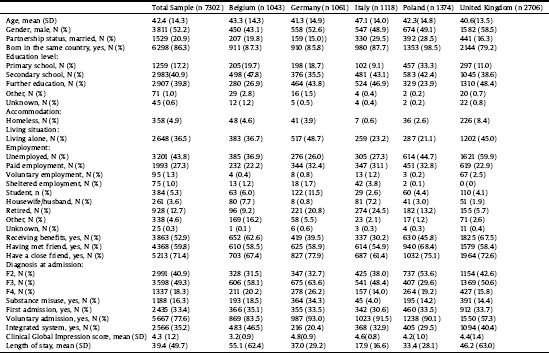

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the total sample and of participants in each country are shown in Table 1.

Overall, 7302 patients were recruited in the study: 1043 in Belgium, 1061 in Germany, 1118 in Italy, 1374 in Poland, and 2706 in the UK.

3.2 Length of stay

The average LoS in the total sample was 39.4 days (standard deviation, SD 49.7). Patients in Belgium had the longest LoS (mean 55.1 standard deviation 62.4, median 24), while patients in Italy had the shortest LoS (mean 17.9, SD 16.6, median 14). Germany, Poland and the UK had average values in between Belgium and Italy: 37.0 days (SD 29.2, median 29), and 33.4 days (SD 28.1, median 26) and 46.2 days (SD 63.0, median 25) respectively, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the samplea.

a Descriptive statistics were calculated only on available data, excluding missing cases.

3.3 Predictor variables

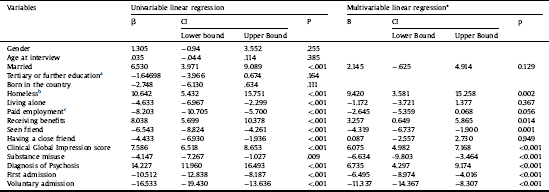

Among tested predictors, twelve of them were entered in the multivariable mixed linear regression to test their association with LoS. Table 2 represents the results of the regression analysis.

Table 2 Mixed linear regression model testing associations of predictors with length of stay.

* Adjusted for the effect of each country as a dichotomous variable and hospital as random intercept.

a Reference category = primary/secondary education.

b Reference category = not homeless.

c Reference category = unpaid employment.

In univariable associations, age, gender and migrant status did not show an association at p <.10 level with LoS. Thus, they were excluded from the subsequent multivariable model. Out of the 12 variables tested in the multivariable model, three indicators of social disadvantage (being homeless, receiving benefits and no contacts with friends in the week before admission) and five indicators of clinical severity (higher CGI score, having a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, having a substance use disorder in comorbidity, history of previous admissions and involuntary legal status) showed a significant association with a longer LoS. The likelihood ratio statistic was 133.2 (distributed chi-squared) & p <.00001, indicating that the fitted model fits significantly better than the null model.

When the means and standard deviations of LoS in each country were adjusted for the influence of all predictor variables that were significant in the multivariable model, the differences between countries slightly changed: Belgium 56.4 days (SD 11.0), Germany 37.4 (SD 10.5), Italy 18.9 (SD 10.4), Poland 30.9 (11.8) and United Kingdom 46.9 (13.9). The differences remained statistically significant (p < 0.001).

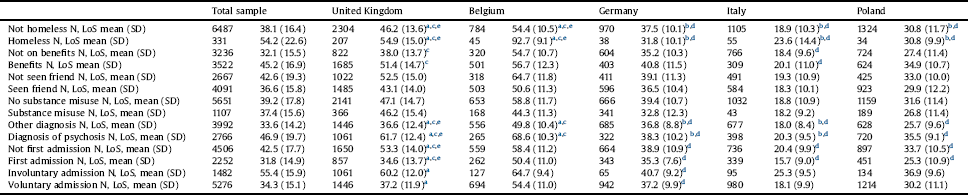

3.4 Interaction effects of predictor variables and countries

Significant interaction effects within country in predicting LoS were found for all these predictors. Thus, their predictive value for LoS was not equal across all five countries. To clarify the differences in the strength of the association of these predictors with LoS in each individual country, Table 3 shows the LoS on a country level for each group of patients with different predictor variables. It also presents pairwise comparisons of interactions.

Major differences in length of stay across different countries for patient groups, with the identified variables, were found. One variable, i.e. homelessness, predicted LoS in opposite directions in different countries. Compared to other patients, homeless patients had a higher LoS in hospitals in Belgium, United Kingdom and Italy, similar LoS in hospitals in Poland, and lower LoS in Germany.

In the other cases the direction of the association was the same, but the extent of the explained difference in LoS was different.

For example, LoS for patients at their first admission was 19 days shorter in the UK, whilst in the other countries the difference of mean LoS of first-admitted patients with those who had already been admitted was equal to (in Belgium) or less than 10 days. Similarly, patients who were involuntarily admitted stayed in hospitals in the UK for 23 days more than those who were voluntarily admitted whilst the difference was less than 10 days in the other countries.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main results

Across a large sample of inpatients in different European countries, several variables can be identified that independently predict LoS. Patients with social disadvantages (being homeless, receiving benefits and no contacts with friends in the week before admission) and higher clinical severity (higher CGI score, having a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, having a substance use disorder in comorbidity, history of previous admissions and involuntary legal status) have a longer LoS. However, the specific impact of these predictors on LoS varies substantially across countries. One variable, homelessness, predicts a different LoS even in opposite directions, whilst for other predictors the direction of the association is the same, but the predictive values of patient-level characteristics are significantly different. After adjusting the mean LoS for significant predictor variables, the differences between countries remain substantial and significant.

4.2 Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are that more than 1000 patients were included in each of five countries with different service organisations and socio-cultural environments, and that a consistent methodology was used across all 57 participating hospitals. The high number of patients allowed us to test a comprehensive set of putative predictor variables as identified by the available evidence in one multivariable model. All hospitalised patients were approached within a few days of admission which may have limited the selection bias, constituting a common problem in studies in inpatient care requiring direct patient contact and written informed consent, particularly in the initial stages of treatment [Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Amos, Leese, Morriss and Rose33, Reference Kallert, Katsakou, Adamowski, Dembinskas, Fiorillo and Kjellin34]. In this study, all patients were interviewed face-to-face by trained researchers. Data on LoS were collected using medical records immediately following patient discharge, with a minimal loss of data (less than 2%).

Table 3 Length of stay (LoS), split by each subgroup − predicted from models including interactions with country, adjusted for significant predictors (n, mean, sd).

Statistical significance (p <.001) of pairwise comparisons in interactions between countries.

Descriptive statistics were calculated on available data for all predictors, excluding missing cases.

a Different from Germany.

b Different from Belgium.

c Different from Italy.

d Different from United Kingdom.

e Different from Poland.

However, the study also has three major limitations. Firstly, we approached all admitted patients but only 50% of them agreed to participate, and the effect of this selection is impossible to establish. However, recruiting people into research (rather than using anonymised data) allowed a detailed assessment of some predictors. Moreover, a selection bias is likely to influence estimates of absolute numbers, so that the distributions of variables reported in this study might not be representative for the participating hospitals and even less so for the given country. Yet, this study focused on exploring associations between variables, which normally are more robust to selection bias than estimates of absolute frequencies, as shown in epidemiological studies Reference Etter and Perneger[35]. Secondly, the number of patients recruited in the UK was much higher than in other countries. To partially overcome this problem for the findings of the overall multivariable predictive model we adjusted for country effect as a fixed variable. Yet, different sample sizes across countries can still influence the statistical significance of pair-wise interaction effects. Finally, we did not collect data on the treatments that patients received in hospital. This may have explained the association of predictor variables with outcomes [Reference Land, Siskind, Mcardle, Kisely, Winckel and Hollingworth36, Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, Magni, Rossi and Barbui37] and also some of the differences of these associations between countries.

4.3 Comparison with the literature

Our findings are largely in line with the extensive literature on predictor variables of LoS in psychiatric in-patient services [Reference Bessaha, Shumway, Smith, Bright and Unick5–Reference Hopko, Lachar, Bailley and Varner27]. Patient characteristics such as age, gender and migrant status were not associated with LoS in univariable models, which was a significant difference from some previous literature. Instead, potentially modifiable indicators of poor social functioning and greater severity of illness were found to predict longer LoS. The multi-variable predictive model in this study showed that these indicators of social functioning and clinical severity have an independent impact on LoS and may therefore need to be targeted separately and specifically.

What this study adds to the existing literature is that the exact predictive value of patient characteristics for LoS varies across different countries. Previous studies conducted in one country each could not explore this, and − again − a substantial sample size in each country and a consistent methodology are required for a reasonable testing of the interaction effects.

One may conclude that the differences in associations between patient predictors and LoS in the literature cannot be explained exclusively by different methodologies used across studies. At least to some extent, there are true differences in the predictive value of variables in different national contexts.

There are several features of national contexts that may explain the differences.

A potentially influential factor is the relative number and availability of psychiatric hospitals beds in the various countries. When the availability of beds is low, clinicians may focus during inpatient treatment on reducing acute symptoms of disorders, and feel under pressure to discharge early, paying less attention to physical comorbidities and social problems. Such problems may not be addressed or left to be dealt with after discharge, by community mental health services or other agencies.

Differences in the legal framework for involuntary hospital treatment may also have an impact on LoS. The timeframe for reviews of involuntary treatments varies across countries, and longer timeframes may lead to a delayed discharge of involuntary patients as compared to those voluntarily admitted.

Another possible explanation may be linked to the availability of social support in the community for people with severe mental disorders. Support through families [Reference He, Ning, Rosenheck, Sun, Zhang and Zhou16–Reference Blais, Matthews, Lipkis-Orlando, Gulliver, Herman and Goodman19] and social networks [Reference Barnow, Linden and Schaub20, Reference Wu, Ouyang, Yang, Li, Wang and Yi21], when available, may facilitate earlier discharges of patients.

Other factors related to the organisation, culture and traditions of mental health care in a given country can all influence clinical practice and decisions for admission and discharge of patients.

Of particular relevance may be funding mechanisms and subsequent financial incentives for earlier or later discharges, be it in state funded or insurance based health care systems Reference Giacco, Bird, Mccrone, Lorant, Nicaise and Pfennig[28]. Funding arrangements are important not only for the hospital treatment itself, but also for the availability of other services such as supported housing settings to accept patients quickly and facilitate earlier discharges. Differences across countries may also be related to varying levels of concerns about malpractice litigations. They may differ according to national legislations on medical responsibility and liability and influence different attitudes of medical professionals on early discharge of patients Reference Mullen, Admiraal and Trevena[38].

4.4 Implications

Future research should aim to disentangle the complex impact of different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients on LoS. This complexity is illustrated by the role of involuntary admissions. Overall, involuntary admission predicted significantly longer LoS, but the country with the highest proportion of involuntary patients, the UK, did not have the longest LoS. Furthermore, the substantial differences in LoS between countries are not explained by any of the predictor variables tested in this study. Thus, characteristics of psychiatric in-patients are predictive of LoS and they do vary across Europe, but they are not the reason for the large country differences in LoS. When we adjusted the LoS for the influence of all the significant predictor variables, the country differences even slightly increased. Thus, country differences in LoS are not explained by different patient characteristics, and research on understanding these differences needs to focus on other factors such as national contexts and practices.

Reducing the LoS of psychiatric in-patient care is a widely expressed aim of policies as shorter LoS is assumed to save money for mental health care. This would apply only if the beds that are freed up by patients who are discharged earlier are not filled with new patients who would not have been hospitalised before. Thus, substantial savings can be achieved only by the closure of beds and requires political decisions. Still, most patients and clinicians are likely to favour shorter LoS and earlier discharges, if possible. Strategies for achieving this may have to include effective social care for the socially disadvantaged patients with longer LoS, arranging professional support through rehabilitation and housing services, but also utilising resources in the patients' families and wider social networks [Reference Priebe, Omer, Giacco and Slade39, Reference Eassom, Giacco, Dirik and Priebe40]. The focus of specific national policies and service organisation for achieving this may vary depending on a range of aspects of the economic, legal and social context.

Studies from countries across the world can certainly help to identify some predictors that are of general importance and have some impact on LoS in very different contexts. However, the value of evidence from international studies for a given national context appears to be limited. Hence, national data is required to understand the complex determination of LoS in psychiatric in-patient care within a country. Such national research should explore more detailed and more specific predictor variables than considered in this study and may benefit from large routine data sets on some predictor variables and LoS, which should be increasingly available in the future. Finally, better descriptions and analyses of social and health care systems in different countries may lead to an understanding of the precise predictive value of similar characteristics in different countries.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the European Commission 7th Framework Programme. Grant agreement number is 602645. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, European Commission or Queen Mary University. The authors would like to grateful acknowledge the support of the funders, participants and wider COFI study group.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.